Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 32

June 11, 2021

The Fog of the Fog of History Wars

History class, Tuskegee Institute, Alabama, 1902. Photo: Frances Benjamin Johnston.

History class, Tuskegee Institute, Alabama, 1902. Photo: Frances Benjamin Johnston.David Blight’s recent essay in the New Yorker, “The Fog of History Wars,” reminds us that the current reactionary assaults on the supposed left-wing threat to historical education are nothing new, but Blight falls short in adequately addressing the urgency of the current battles in the latest incarnation of the history wars.

The current bogeymen of critical race theory or the 1619 Project, Blight reminds us, are merely incarnations of the trumped up charges of the culture wars during the 1980s and 90s. They are perhaps even vestiges of earlier claims that educators could sneakily brainwash America’s youth with communism during the Cold War, or teach them about evolution and monkeys instead of Adam and Eve, the bible, and old-time religion. So much for a thorough defense of free speech by conservative free speechers. It’s as if America’s children, or any American for that matter, is so feeble of mind that they wouldn’t be able to stand a thorough reckoning with the truths of the American past.

This urge to limit historical education, as Blight is quick to point out, made no sudden appearance in American life. Reviewing past incidents such as the National Standards for History debates or the Enola Gay Smithsonian Air and Space Museum controversy of the early 1990s, Blight frames long-running and key questions in the field of public history, questions that are about the broader issue of creating American history for the American public. “The broader problem,” Blight writes:

is that, in the realm of public history, no settled law governs. Should the discipline forge effective citizens? Should it be a source of patriotism? Should it thrive on analysis & argument, or be an art that emotionally moves us? Should it seek to understand a whole society, or be content to uncover that society’s myriad parts?

For Blight, “The answer to all of these questions is essentially yes.” What then, he wonders. As he wryly points out, despite their claims that they are losing the battle against the forces of historical radicalism, “The American right, for all its complaints about liberal bias, wins more than its share of these battles.”

So what is to be done?

Here the essay begins to turn in strange directions.

Blight calls for a spirit of being “chastened by knowledge” when facing the traumas of US history. “Slavery,” he writes, “as personal experience and national trial, is a harrowing human tragedy, and like all great tragedies it leaves us chastened by knowledge, not locked within sin or redemption alone.” This is not wrong, but it does seem to border, perhaps unintentionally, on the complacent. It sounds like the voice of someone in comfortable authority, looking down from the ivory tower condescendingly on other Americans. It is close to smug. How would being “chastened by knowledge” enable a forceful reckoning with the “sins” of US history at all, never mind the unfinished, if even possible, quest for “redemption”? It might be able to do that, perhaps, but Blight does not explain how. This leaves the claim sounding almost conservative in its sense of resignation with the sins of history. Chastened knowledge in this framing could slip easily into disenchanted apathy and passivity. That’s just the way life is, always has been, and always will be.

Surely, Blight doesn’t really mean to suggest this perspective. After all, in the essay, he has just spent the previous paragraph girding his loins for the battles ahead with conservatives in the ongoing history wars. He contends that:

…we who care about it have to fight this war better and more strategically ourselves. We will not win by constantly telling the public that they need to see all of American experience in a “reframing” of slavery and racism. We need to teach the history of slavery and racism every day, but not through a forest of white guilt, or by thrusting the idea of “white privilege” onto working-class people who have very little privilege. Instead, we need to tell more precise stories, stories that do not feed right-wing conspiracists a language that they are waiting to seize, remix, and inject back into the body politic as a poison.

Yet arguing for the need to “tell more precise stories,” Blight goes ahead and gets imprecise. First, he calls for historians to write only plainspoken prose “our grandmothers can read.” What is it with the grandmas putdown? They might be the most theoretically bunch sophisticated around these days. Perhaps Americans (especially grandmas) long for prose that does not speak down at them. They might well want, they might well need prose whose tones do not settle for clarity to the point of oversimplification. They’ve seen life. They can handle it. Many may well already have worldviews “chastened by knowledge.” They can likely handle precision, complexity, ambiguity. They can handle sophistication.

Then, Blight turns to an even more imprecise closing quote. He takes it from the recent writing of George Packer (not a historian by training, although a journalist very interested in history). He quotes Packer’s recent book Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal:

America is neither a land of the free and home of the brave nor a bastion of white supremacy. Or rather, it is both, and other things as well. . . . Neither Sinful America nor Exceptional America, neither the 1619 Project nor the 1776 Report, tells a story that makes me want to take part. The first produces despair, the second complacency. Both are static narratives that leave no room for human agency, inspire no love to make the country better, provide no motive for getting to work.

This seems like even more precisely the kind of imprecise characterization of the past that Blight urges historians not to adopt. As Blight himself immediately grants (“We can debate whether Packer undervalues the 1619 approach, or whether he accounts for the sheer level of willful ignorance in the 1776 Commission report…”), Packer’s statement is bothsiderism at its worst. it is clumsy and distorted history of the recent past’s history wars. Maybe in striving to speak to the imagined grandmothers, Packer equates left and right, 1619 Project and 1776 Project. But in doing so, he renders myth, not history. Despite its melodramatic tone & journalistic simplifications of complex history (also aiming for the imagined public of grandma readers? Is this a journalism problem more than a history problem?), the 1619 Project is nonetheless filled with efforts to “make the country better,” certainly far more so than the drivel of the 1776 Commission report. “We need history that can get us marching but also render us awed by how much there is to learn,” Blight urges. There is plenty of that spirit in the 1619 Project despite its flaws.

Whatever the ideal history might be that, as Blight puts it “not only tolerates the reinterpretation of its past but thrives upon it” in order to support the flourishing of a “genuine democracy,” it’s not to be found in Packer’s quote. True, it is also not to be found in the substitution of training sessions and rote, preordained lesson plans for ample, extended, well-funded, grassroots educational study and dialogue. And it is certainly not to be found in silencing voices or banning books or outlawing ideas.

What it does demand, as Blight points out, is precision. It certainly can express the sense of humility that comes with studying history: “how much there is to learn.” And it asks for a genuinely democratic approach to public history—one that listens to and speaks with grandmothers rather than talking down to them. But maybe, this history can also be pretty fiery, pretty confrontational, unafraid to reckon with despair, to see sin, and yet still to seek redemption. This kind of history has a “motive” to see the fog with precision, in all its textured thickness, to own up to just how far it stretches into the past behind us. Yet also to glimpse the light that occasionally streams in—the vistas that beckon us to see our way forward not beyond the fog, into the clear, but through it, retracing and retracing our steps, as accurately as possible.

Facing the Berlin Wall

Dominic Cooper as Fielding Scott in AMC’s Spy City.

Dominic Cooper as Fielding Scott in AMC’s Spy City.Set in Berlin in the early 1960s, just before East Germany put up the Berlin Wall, AMC’s Spy City is a fairly conventional Cold War tale of intrigue in the John Le Carré mode of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. But the twists of the plot are not really the thing that make it interesting. Neither is some kind of deeper investigation of the politics and culture of the Cold War. Spy City is not even much of a psychological study of character and moral ambiguity. Instead, the real spyscape worth watching is lead actor Dominic Cooper’s face, in particular how many ways he can figure out to express disgust—with lovers, bosses, institutions, politics, humanity, and maybe most of all with himself.

At the end of the first season, as the barbed wire goes up where the Berlin Wall will eventually be built and cuts off Cooper’s character from important contacts in the East, he summons up a facial expression for the ages, a study of disgust that plumbs the many elements of the emotion: shame, loss, abjectness, physical illness, but also a hint of fascination with and maybe even an attraction to the feeling of disgust itself. In the momentary sneer and wrinkle of Cooper’s face at the end of the season, Spy City cracks for an instance. A fairly conventional contemporary television drama splits open to reveal the full emotional scream of a fateful historical moment.

May 31, 2021

Rovings

Amdavad ni Gufa, designed by the architect Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi, Ahmedabad, India.SoundsRogue Madame, Rogue MadameLembe Lokk, Comment te traduireVarious Artists, Traditional Music of the Garifuna of BelizeVarious Artists, Dabuyabarugu: Inside the Temple—Sacred Music of the Garifuna of BelizeHuele de Noche featuring Angelina Almukhametova & Dann Disciglio, Jada-Amina, Las Chikatanas, Jesús Hilario-Reyes, Marisol Mendoza, Experimental Sound StudioEiko Ishibashi, EXITMR-0760, Derek Bailey at Lower Links, 12-1-1989Neil Young and Crazy Horse, Way Down in the Rust BucketThe Neville Brothers, Yellow MoonDucks, LTD., Get BleakWordsExile BBC podcastAnnika Stranded BBC podcastJames Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans BBC podcast Haruki Murakami, The Wind-Up Bird ChronicleDoris Lessing, The Good TerroristMark Allan Jackson, ed., The Honky Tonk on the Left: Progressive Thought in Country MusicPerry Lewis, Intellectual Life in America: A HistoryDoris Sommer, The Work of Art in the World: Civic Agency and Public HumanitiesDavid J. Elliott, Marissa Silverman, and Wayne D Bowman, eds., Artistic Citizenship: Artistry, Social Responsibility, and Ethical PraxisRachel Bowditch, Jeff Casazza, and Annette Thornton, eds. Physical Dramaturgy: Perspectives from the FieldLinda Tunisia Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous PeoplesColin Koopman, How We Became Our Data: A Genealogy of the Informational PersonVilém Flusser, Post-HistoryShane Denson, Discorrelated Images“Walls”Pleasures and Possible Celebrations: Rosemary Mayer’s Temporary Monuments, 1977-1981, Gordon Robichaux Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Wrightwood 659Take Care, Smart MuseumClaudia Wieser: Generations, Smart MuseumK. Kofi Moyo and FESTAC ’77: The Activation of a Black Archive, Logan Center ExhibitionsHowardena Pindell: Rope/Fire/Water, The ShedMarking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, MoMA PS1Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented, 1918–1939, MoMAJamal Cyrus: Manna and Braised Collards, Patron Gallery “Stages”Lee Mingwei and Bill T. Jones, “Our Labyrinth, Live Performance” 1, 2, 3Cubique, Alone TogetherScreensSpy CitySmall Axe: Alex WheatleShadow Lines

Amdavad ni Gufa, designed by the architect Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi, Ahmedabad, India.SoundsRogue Madame, Rogue MadameLembe Lokk, Comment te traduireVarious Artists, Traditional Music of the Garifuna of BelizeVarious Artists, Dabuyabarugu: Inside the Temple—Sacred Music of the Garifuna of BelizeHuele de Noche featuring Angelina Almukhametova & Dann Disciglio, Jada-Amina, Las Chikatanas, Jesús Hilario-Reyes, Marisol Mendoza, Experimental Sound StudioEiko Ishibashi, EXITMR-0760, Derek Bailey at Lower Links, 12-1-1989Neil Young and Crazy Horse, Way Down in the Rust BucketThe Neville Brothers, Yellow MoonDucks, LTD., Get BleakWordsExile BBC podcastAnnika Stranded BBC podcastJames Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans BBC podcast Haruki Murakami, The Wind-Up Bird ChronicleDoris Lessing, The Good TerroristMark Allan Jackson, ed., The Honky Tonk on the Left: Progressive Thought in Country MusicPerry Lewis, Intellectual Life in America: A HistoryDoris Sommer, The Work of Art in the World: Civic Agency and Public HumanitiesDavid J. Elliott, Marissa Silverman, and Wayne D Bowman, eds., Artistic Citizenship: Artistry, Social Responsibility, and Ethical PraxisRachel Bowditch, Jeff Casazza, and Annette Thornton, eds. Physical Dramaturgy: Perspectives from the FieldLinda Tunisia Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous PeoplesColin Koopman, How We Became Our Data: A Genealogy of the Informational PersonVilém Flusser, Post-HistoryShane Denson, Discorrelated Images“Walls”Pleasures and Possible Celebrations: Rosemary Mayer’s Temporary Monuments, 1977-1981, Gordon Robichaux Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, Wrightwood 659Take Care, Smart MuseumClaudia Wieser: Generations, Smart MuseumK. Kofi Moyo and FESTAC ’77: The Activation of a Black Archive, Logan Center ExhibitionsHowardena Pindell: Rope/Fire/Water, The ShedMarking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, MoMA PS1Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented, 1918–1939, MoMAJamal Cyrus: Manna and Braised Collards, Patron Gallery “Stages”Lee Mingwei and Bill T. Jones, “Our Labyrinth, Live Performance” 1, 2, 3Cubique, Alone TogetherScreensSpy CitySmall Axe: Alex WheatleShadow Lines

May 26, 2021

May 23, 2021

What Is Dramaturgy?

Dramaturgy is for me learning to handle complexity. It is feeding the ongoing conversation on the work, it is taking care of the reflexive potential as well as of the poetic force of the creation. Dramaturgy is building bridges, it is being responsible for the whole, dramaturgy is above all a constant movement. Inside and outside. The readiness to dive into the work, and to withdraw from it again and again, inside, outside, trampling the leaves. A constant movement.

Marianne Van Kerkhoven

May 21, 2021

Endless MacGuffins

Could a drama consist only of MacGuffins, those famous plot devices that push the plot along, but fade from significance as a story unfolds?

In a 1986 essay, the critic Nick Lowe imagined multiple MacGuffins as plot coupons, and sometimes the Radiotopia podcast Passenger List feels like it might pull off the trick of sustaining a story entirely on them. The story keeps unfolding and unfolding, its MacGunnins like a Russian matryoshka doll. It’s a wonderful way to approach the serial quality of the audio podcast, a form that really is just radio with a new kind of distribution model.

One Should Never Be Where One Does Not Belong

Register for the virtual conference.

Register for the virtual conference.in 2018, esteemed co-panelist and fearless Bob Dylan Institute leader Sean Latham and historian Brian Hosmer, then at the University of Tulsa, now at Oklahoma State University, invited me to contribute an essay about Bob Dylan and the counterculture for the new book The World of Bob Dylan. This was an interesting but also challenging task. After all, Bob Dylan is at once deeply associated with the 1960s counterculture and yet also has said repeatedly that he wants nothing to do with it.

Trying to sum up the complex, fraught relationship between these two already slippery topics—Dylan, the counterculture—would be no easy thing. Dylan doesn’t stay in place. We all know that. Neither, the more you study it, does the counterculture, that magic swirling ship of social energies formed by people who sought to imagine and enter into a new kind of modern life, different from what was on offer in the mainstream during the decades after World War II.

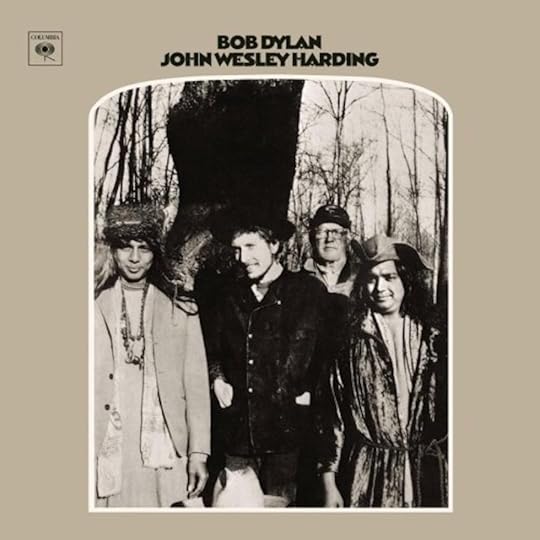

I decided one way—not the only way of course, but one way—in to the relationship of Dylan and the counterculture might be to focus on the album John Wesley Harding and the pivot Dylan made in 1967 from the high-hipster, going electric, howling “how does it feel?” phase of his career to his post-motorcycle accident, backwoods mystic, allegorical preacher, domestic country-squire, Basement Tapes period. The John Wesley Harding moment, always shrouded in mystery, struck me as one way to get a view on where Dylan and the counterculture met in the 1960s. Did the archive have anything new to tell us about this time period?

It did. But other questions emerged too from being able to work in the Bob Dylan Archive. I’d like to line three of them out today, ever so briefly, in the time I have left. The first is a critic’s question and has to do with Dylan as artist. The second is a historian’s question and has to do with what Dylan’s art can tell us about the larger times in which he lived. And the third is a theoretical question: what do we learn about archives from all this Dylanology? What are archives, how do they work, why they matter?

Question one: what do we learn about Bob Dylan and his art when we can now access his official archive?Going into the Bob Dylan Archive to investigate John Wesley Harding, all I could hear in my head was that warning from “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest”: “One should never be where one does not belong.” It is “the moral of the story / The moral of this song,” after all. There is something forbidden, improper, even sullying about seeking to access the man behind the shades, to rifle through his papers and notebooks, to peek into his private archive. Dylan has always requested, even insisted, that we not go there, that we respect his privacy.

What one discovers looking through Dylan’s notebooks and scraps of paper, listening to the outtakes of John Wesley Harding, leafing through other ephemera is that the artist behind the shades is the artist in front of them, under the spotlight. Dylan as artist is porous, open, a filter, a diaphragm. His process absorbs the world, registers it, and refashions it for consideration. That’s his artistic brilliance. And it shows in the official Bob Dylan Archive. You glimpse Dylan doing just what we think he would be doing. He sifts and considers, sorts and collects, observes and mutates, rearranges and revises. During the time around John Wesley Harding, his notebooks show him slowly rethinking the kind of song style he wanted to create, and doing so partly in response to the changing times of psychedelia and counterculture, rock music and its excesses, the Vietnam War and antiwar resistance, an America and a world seemingly coming apart at the seams yet also, as the poet Gary Snyder has written, at a juncture in time “when it seemed the world might head a new way.”

This leads to my second question: not just what does the archive tell us about Dylan as artist, but also what light does Dylan’s art shine on the larger times in which he lived?Dylan, we know, increasingly wanted nothing to do with the counterculture by late 1967, if not before that. As he wrote years later in Chronicles, noting the annoyance of people constantly invading his private life in Woodstock, “Whatever the counterculture was, I’d seen enough of it.” Or as he wrote on a scrap of paper some time in the late 1960s: “I’d hate to think I was speaking for a generation, I’d like to think I was speaking for myself too.”

His new style may not have spoken for a generation; but it did speak to a generation. Much as Dylan seemed to be backing away from the counterculture as it roared around him, retreating into a private world, he also, as an artist, joined the ongoing cultural and musical debate about what the counterculture was exactly and what it should or might be. Should hippies zoom into a druggy, psychedelic fantasia with the Beatles on Sgt. Pepper, for instance? Dylan didn’t like that sound and style much and sought out a different quest, a more pastoral one that sought not to reject the past, but draw upon it, that sought not to abandon history so much as try to get back to the past, reconnect with it, see what it had to offer for present conundrums and dilemmas.

He wanted to breathe the air around Tom Paine. He pitied the poor immigrant. He wanted to go back to the Bible, which he was reading intently at the time (there are long lists of biblical citations in his notebooks). He was curious about what St. Augustine had to say as much as Sgt Pepper. He wanted to know what the story was with Judas Priest, and how the outlaw John Wesley Harding had handled things, or how, somewhere on a medieval watchtower, a joker and a thief debated their next move as a mysterious rider approached and the winds began to howl.

Listeners, critics, fans, the public received Dylan’s John Welsey Harding as drawing upon reconfigured fragments of the past to try to make sense of the present. As future Bruce Springsteen manager Jon Landau put it in a 1968 review, John Wesley Harding expressed “a profound awareness of the [Vietnam] war and how it is affecting all of us.” This was the case even as, to quote the music critic Robert Christgau in a review from the time, “instead of plunging forward, Dylan looked back. Instead of grafting, he pruned.”

With its fresh renewal of his long-running interest in what ancient, mystic, and historical folk culture could bring to the contemporary moment, Dylan’s John Wesley Harding joined debates of the time about what the counterculture might be, what it might become. It helped, in this way to constitute the counterculture itself, to make the counterculture not just a party zone of sex, drugs, and rock and roll—though it was that too—but also to make it a medium for contemplating, wondering, questioning, and considering what the options were, where the dangers lurked, in the effort to turn the self and the world in better directions.

To close, then, with my theoretical question: what do we learn about archives—what they are, how they work, why they matter—from all this Dylanology?The Official Bob Dylan Archive, capital A, might seem like a thing apart from the long history of archiving Dylan. I’d argue the opposite. It might best be understood in continuity with the long history of tracking, preserving, tracing, and studying Dylan’s art. In this way the Official Bob Dylan Archive even raises the issue of what an official archive is exactly, where it ends and other modes of memory and memorialization begin, and how an archive relates to the person it ostensibly archives.

My Official Dylan Archive visit, for instance, quickly led to connections with a world of collectors—unofficial archivists really—who graciously shared items, ideas, and more. This got me to thinking about what, who we mean when we say “Bob Dylan.” To be sure it’s the artist himself, but it’s also the larger phenomena his art constitutes. The World of Bob Dylan, indeed.

What is official, anyway? What is bootlegged? What is inside? What is out? When are we at the Official Bob Dylan Archive and when are we inching toward the AJ Weberman Society for Garbology, sifting through the man’s trash cans? In short, where are we exactly when we conduct research in the Bob Dylan Archive?

We might sometimes find ourselves where one does not belong, it’s true. Maybe that’s a time to look away. But maybe the official archive is not just a tawdry affair. Instead of fetishizing the Dylan Archive as a secret lair, what if instead we think of it as a springboard for community, maybe even as a constituter of counterculture. At the very least, the Bob Dylan Archive allows us to try to climb up atop the stuff of a lifetime to get a glimpse at the past and the future—how it all connects, what our fates might be. The archive can be less a vault, more a watchtower.

May 19, 2021

May 17, 2021

Sounds Beyond Sounds

Musicians are always making deals with the dark side. They are trying to say something that cannot really be said, not only not with words but not really with music either.

David Rothenberg, Nightingales in Berlin: Searching for the Perfect Sound