Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 27

December 31, 2021

Rovings

Paolo Arao, Measurements (2020), sewn cotton, canvas, and acrylic, 33 x 27 x 1/4 inches. Photo: Cary Whittier.SoundsDon Juan, BBC SoundsThe Tempest, BBC SoundsWinter Solstice, BBC SoundsMusic Of The World’s People Volumes 1-5 (Folkways Records), edited by Henry CowellBeethoven, Bebop & Pagpipes – 1926-1950 – Program 12.13.2021, Gramaphoney BaloneyNeil Young, Summer SongsWIlliam Parker on Myself With Others with Adam ShatzNavarra Quartet, Peteris Vasks: String Quartets Nos. 1-3WordsDoris Lessing, The Golden NotebookYunte Huang, Charlie Chan: The Untold Story of the Honorable Detective and His Rendezvous with American HistoryJacqueline Jones, Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American RadicalAndrew F. Jones, Circuit Listening: Chinese Popular Music in the Global 1960sMaureen A. Flanagan, America Reformed: Progressives and Progressivisms, 1890s-1920sRaphael Rubinstein, Critical Mess: Art Critics on the State of Their PracticeJames Elkins and Michael Newman, eds., The State of Art CriticismTrevor Stack, Jeffrey C. Alexander, and Farhad Khosrokhavar, eds., Breaching the Civil Order: Radicalism and the Civil SphereWalls and “Walls”AbStranded: Fiber and Abstraction in Contemporary Art, Everson Museum of ArtMutual Affection: The Victoria Schonfeld Collection, Everson Museum of ArtStages and “Stages”Berkeley Old Time Music ConventionFive People, Sangliers (The Bridge #14), Constellation ChicagoElla Rothschild, Pigulim, PlayBACScreensThe BooksellersBaghdad Central, Season 01Curb Your Enthusiasm, Season 13Hawkeye, Season 011983, Season 01Stanley Tucci: Searching for Italy, Season 01

Paolo Arao, Measurements (2020), sewn cotton, canvas, and acrylic, 33 x 27 x 1/4 inches. Photo: Cary Whittier.SoundsDon Juan, BBC SoundsThe Tempest, BBC SoundsWinter Solstice, BBC SoundsMusic Of The World’s People Volumes 1-5 (Folkways Records), edited by Henry CowellBeethoven, Bebop & Pagpipes – 1926-1950 – Program 12.13.2021, Gramaphoney BaloneyNeil Young, Summer SongsWIlliam Parker on Myself With Others with Adam ShatzNavarra Quartet, Peteris Vasks: String Quartets Nos. 1-3WordsDoris Lessing, The Golden NotebookYunte Huang, Charlie Chan: The Untold Story of the Honorable Detective and His Rendezvous with American HistoryJacqueline Jones, Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American RadicalAndrew F. Jones, Circuit Listening: Chinese Popular Music in the Global 1960sMaureen A. Flanagan, America Reformed: Progressives and Progressivisms, 1890s-1920sRaphael Rubinstein, Critical Mess: Art Critics on the State of Their PracticeJames Elkins and Michael Newman, eds., The State of Art CriticismTrevor Stack, Jeffrey C. Alexander, and Farhad Khosrokhavar, eds., Breaching the Civil Order: Radicalism and the Civil SphereWalls and “Walls”AbStranded: Fiber and Abstraction in Contemporary Art, Everson Museum of ArtMutual Affection: The Victoria Schonfeld Collection, Everson Museum of ArtStages and “Stages”Berkeley Old Time Music ConventionFive People, Sangliers (The Bridge #14), Constellation ChicagoElla Rothschild, Pigulim, PlayBACScreensThe BooksellersBaghdad Central, Season 01Curb Your Enthusiasm, Season 13Hawkeye, Season 011983, Season 01Stanley Tucci: Searching for Italy, Season 01

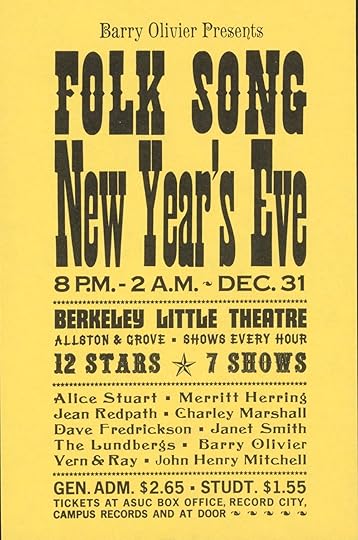

Happy New Year’s Eve From the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project

For more from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project visit bfmf.net.

December 25, 2021

Merry Christmas & Happy Holidays From the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project

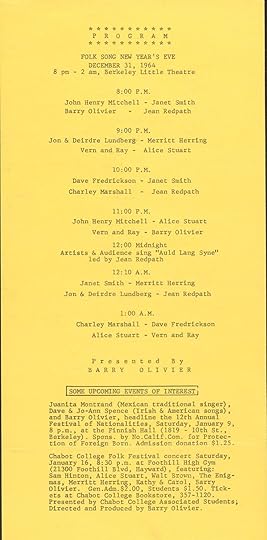

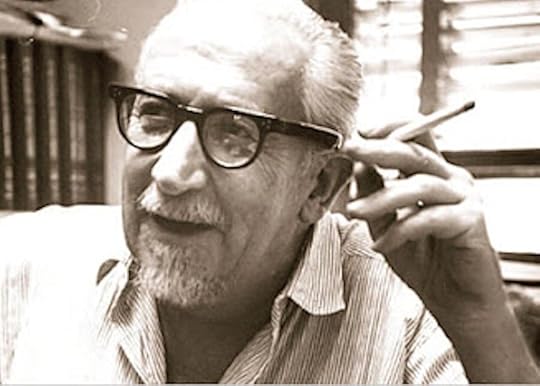

Ralph Rinzler at the 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Roland Jacopetti.

Ralph Rinzler at the 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Roland Jacopetti. Ralph Rinzler at the 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Dan Paik, later of the Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band, sits on the left. Photo: Roland Jacopetti.

Ralph Rinzler at the 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Dan Paik, later of the Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band, sits on the left. Photo: Roland Jacopetti. Dan Paik, later of the Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band, plays guitar at the 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Roland Jacopetti.

Dan Paik, later of the Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band, plays guitar at the 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Roland Jacopetti.

Supply Chain of Fools

Ryan Johnson’s trucker driver seat perspective on the current supply chain crisis in the US and the world—“I’m A Twenty Year Truck Driver, I Will Tell You Why America’s ‘Shipping Crisis’ Will Not End”—reveals how broken this industry at the heart of so many other industries is. The supposed laws of supply and demand do not end in equilibrium. When it comes to supply chains, they have ended up in imbalance. Independent-contractor truckers are unable to make a living, ending up in a kind of modern-day sharecropper system. Shipping companies, meanwhile, profit not by improving efficiencies, but rather by being more inefficient. Goods pile up, with nowhere to go. So much for logistics ruling the day, for the market as currently constructed sorting things out. Run on a supposed free market model, the shipping industry shows, at least in Johnson’s essay, how unfree markets can actually turn out to be.

But the response here is likely not markets or no markets. The invisible hands are missing in action, but total state control likely wouldn’t work either. It’s worth stepping back to think more critically how, when it comes to supply chains, markets are what we make them. After all, we forget that invisible hands are attached to arms, bodies, and heads. They grip with power directed by someone, somewhere. We call analyzing the dynamics of that clutching for control political economy. We can notice how the hands are not invisible at all. At the same time, markets are also cultural creations. Their logistics are not purely immaterial, invisible hands guiding them to perfect balance; nor are they solely material, ruled by iron fists of market laws.

We might grasp instead that supply chains are forged by struggles over who gets what, on what terms, by what rules. Markets that are only functional because of these supply chains are, ultimately, what we want them to be. They are customizable, linked together by hand shakes as well as invisible hands. They ask us to consider what our duties are to each other. They are created and sustained by customs.

December 19, 2021

Only in Music

Judita Leystar, Two Musicians (1629).

Judita Leystar, Two Musicians (1629).There are these rare moments when musicians together touch something sweeter than they’ve ever found before in rehearsals or performance, beyond the merely collaborative or technically proficient, when their expression becomes as easy and graceful as friendship or love. This is when they give us a glimpse of what we might be, of our best selves, and of an impossible world in which you give everything you have to others, but lose nothing of yourself. Out in the real world there exist detailed plans, visionary projects for peaceable realms, all conflicts resolved, happiness for everyone, for ever—mirages for which people are prepared to die and kill. Christ’s kingdom on earth, the workers’ paradise, the ideal Islamic state. But only in music, and only on rare occasions, does the curtain actually lift on this dream of community, and it’s tantalizingly conjured, before fading away with the last notes.

— Ian McEwan, Saturday

December 16, 2021

Music of the Mind

Music can represent a kind of systematic exaggeration of the rhythm and intonation of speech. A given musical idiom can therefore operate in a manner very similar to the emotional lexicon itself. Singing a given phrase with a certain kind of melody is similar to stating it with certain facial expressions, or qualifying its statement with an emotion term. There is a disengaged rapport among the various elements of the art form, similar to that which characterizes a bundle of related proto-intentions. Harmony, melody, lyrics, orchestration, phrasing, and intonation combine to suggest an orientation in the same way that emotional expression often suggests. Our everyday thinking is more like music than like logic.

— William Reddy, “The Logic of Action: Indeterminacy, Emotion, and Historical Narrative,” History and Theory

December 13, 2021

SUNY Brockport History Major Completes Student Apprenticeship with the BFMF Project

Research assistant Olivia Langa, SUNY Brockport history major ’22, with project director Dr. Michael J. Kramer, assistant professor of history at SUNY Brockport.

Research assistant Olivia Langa, SUNY Brockport history major ’22, with project director Dr. Michael J. Kramer, assistant professor of history at SUNY Brockport.X-posted from Brockport Today.

Olivia Langa has spent two semesters as a research assistant for Dr. Michael J. Kramer’s NEH-funded Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project, a digital public history project documenting a folk music festival that took place at the University of California from 1958 to 1970.

Researching and curating digitized archival photographs and other documents, completing reports on the development of digital lesson plans and an audio podcast, and other tasks, history major Olivia Langa has made use of a Student Apprenticeship Mini-Grant (SAMG) from the SUNY Brockport Scholar and Grants Development Office to make vital contributions to the NEH-funded Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project, a digital public history project directed by Department of History Assistant Professor Dr. Michael J. Kramer that documents a folk music festival which took place on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, from 1958 to 1970.

In both spring and fall semesters of 2021, Olivia used the SAMG to develop her skills of digital and historical research, editing, and communication. These are widely applicable and useful to whatever career Olivia chooses to pursue, and evidence of the power of studying history and pursuing an undergraduate liberal arts and sciences education at Brockport. Olivia plans to continue to develop her experiences of bringing together history and digital technology through a spring 2022 internship with SUNY Brockport Department of History Assistant Professor Dr. Elizabeth Masarik’s Dig history podcast project. Upon graduation, she hopes to pursue a Public Administration masters degree while considering a range of career paths in historical education, museum work, law, public policy, or another field.

The Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project is a multimodal digital public history project that explores the significance of a folk music festival that took place at the University of California, Berkeley, between 1958 and 1970. The Festival’s archive resides at Northwestern University Libraries and its 33,500 artifacts includes photographs, posters, business records, sound, video, and ephemera, many of which have never been publicly available. They are now fully digitized through the support of an National Endowment for the Humanities Access and Preservation Grant. An introductory digital exhibit curated by SUNY Brockport Assistant Professor Dr. Michael J. Kramer (with Olivia’s assistance!) allows both newcomers and aficionados to explore the story of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival and the less studied folk revival on the West Coast of the United States during the 1960s. The exhibit can be viewed online. Dr. Kramer continues to conduct research and curate the archive through an NEH Digital Projects for the Public Discovery Grant, awarded in 2021. For more about the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project, visit BFMF.net.

December 4, 2021

History Does Not Compute

X-posted from Society for US Intellectual History Book Review .

In her new book, If Then: How the Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future, Jill Lepore recovers the forgotten story of Simulmatics, which she describes as “Cold War America’s Cambridge Analytica.” Founded in the late 1950s, Simulmatics was gone by the early 1970s. During its brief life it sought to combine the collection of personal data with the then-new field of the behavioral science as well as the then-just invented new device of the computer in order to predict what humans would do. Hoping to profit through prophesy and failing at it, Simulmatics itself turned out to predict the future: Lepore argues that its demise offers a chilly warning for our obsession today with predictive analytics and the effort to transform human experience into quantifiable data.

Imagining that they could create what founder Ed Greenfield called a “People Machine,” the men who formed Simulmatics believed they could accurately foretell how individuals would vote, what they would buy, when they might riot, even how they might wage war. At first, the company garnered fame by seeming to help John F. Kennedy win the 1960 presidential election, but it eventually went bankrupt after controversial programs related to the American military intervention in Vietnam and the urban riots and inner-city woes of 1960s United States. Simulmatics ended with a whimper, yet many of its ideas would resurface a few decades later in the tactics of Google, Facebook, Palantir, Amazon, Uber, and other contemporary technology companies. These latter-day Simulmatics have flourished by collecting and processing user data, just as their forebearer did. Telling the story of their Simulmatics’ rise and fall, Lepore shows us how the past matters: not as prognosis, but rather as admonition; not as easy remedy, but rather as an act of remonstrance. In If Then, the sordid history of tech is here to teach its present-day practitioners a lesson.

Lepore’s book is far more than a narrow academic study, but it nonetheless offers a revision of the dominant scholarly interpretation of the origins of Silicon Valley. While many now follow Fred Turner’s contention that today’s “cyberculture” arose from the 1960s counterculture by way of Whole Earth Catalog editor Stewart Brand, Lepore notices instead the fundamental connections between mid-twentieth century technocratic liberalism and our Internet dystopia now.[1] She points out, for instance, that in the 1980s Brand moved from his ecstatic writing about hippie Spacewar programmers in the pages of Rolling Stone during the 1970s to celebrate much more enthusiastically the information and communications social scientist Ithiel de Sola Pool. Pool was no hippie. In fact, hippies and other New Leftists fiercely protested Pool’s involvement in Vietnam War research when he was a professor at MIT. Brand, however, loved Pool’s books Technologies of Freedom and Technologies without Boundaries, key texts by the 1990s for the libertarian and Newt Gingrich-affiliated Progress and Freedom Foundation’s Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age. Where did Pool do much of his work in the 1960s? Simulmatics.[2]

Much as the company was emblematic of the technocratic hubris of Cold War corporate liberalism, Simulmatics was not, as Lepore tells the tale, a place of soulless men in drab lab coats. Its first days, after all, were spent in a geodesic dome built on a Long Island beach by Buckminster Fuller. The strangeness of all this was largely the doing of advertising executive Greenfield. Watching Remington Rand’s UNIVAC computer spit back predictions for the 1952 presidential election with seeming magic on a CBS News broadcast (it worked so well in predicting Dwight Eisenhower’s rout of Adlai Stevenson that Remington Rand’s man at CBS was too hesitant to share its findings early on election night), Greenfield began to imagine Simulmatics as a company that could help the Democratic Party win elections, something it was struggling to do during the era of Eisenhower. Greenfield, the Dr. Strangelovian Pool, the manic-depressive mathematician Bill McPhee, and others involved with Simulmatics became, Lepore contends, the “long-dead, white-whispered grandfathers of Mark Zuckerberg and Sergei Brin and Jeff Bezos and Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen and Elon Musk” and “the Simulmatics Corporation is the missing link in the history of technology, a clasp that fastens the first half of the twentieth century to the beginning of the twenty-first.” If it failed as a business, technology company, and “data-driven” firm, Simulmatics nonetheless show us how postwar technocratic liberals imagined what Lepore ominously describes as “a future in which humanity’s every move is predicted by algorithms that attempt to direct and influence our each and every decision through the simulation of our very selves.” The world forgot Simulmatics, but it didn’t forget us.

Yet it is not Simulmatics itself that is crucial to Lepore, but instead the ideas that gave rise to it and that it in turn advanced during its decade of existence. In this sense, Lepore’s book is intellectual history at its finest. It connects seemingly ephemeral archival esoterica to the larger significance of what we think and how we think. If Then also answers the call by many recent historians to write for broader audiences and not merely for other specialists. Lepore has a knack for uncovering quirky archival stories that turn out to explain present-day situations. Among her many books, The Secret History of Wonder Woman pointed to how the links between first and second wave feminism lurked in the concealed story of Wonder Woman’s eccentric creators. In Joe Gould’s Teeth, Lepore discovered the remnants of a supposedly fictitious manuscript by an infamous New York bohemian, which then offered a glimpse into the Harlem Renaissance, modernist literature in postwar New York City, and troubling issues of race and sex. Other studies explore King Philip’s War, slave uprisings in colonial New York City, Noah Webster and other investigators of American language, the Tea Party of the Revolutionary War and the Obama era, and a history about ideas of life and death in the United States. Lepore has become something of the literary crowd’s Michael Beschloss or Doris Kearns Goodwin. And her politics—liberal, but not technocratic—make her a kind of modern-day Richard Hofstadter. Yet because her biggest strengths as a historian are in her original field of study, colonial American history, and in modern US history, she has garnered backlash in some academic corners. Her survey of US history These Truths: A History of the United States, for instance, registered complaints by nineteenth-century experts such as Richard White. This might have been in part due to different political ideologies and minor errors of interpretation and detail by Lepore, but it also seems to be about tone and style of writing (and maybe a faint a whiff of jealousy or even misogyny).[3]

Despite the criticism, there is no denying that Lepore’s prose, with its intensified drama and many evocative turns of phrase, raises the stakes of historical narrative. If Then borrows tactics from fiction: a startling opening, a story arc, a focus on telling details rather than dry, abstracted prose. Take the memorable opening line: “The scientists of the Simulmatics Corporation spent the summer of 1961 on a beach on Long Island beneath a geodesic dome that looked as if it had landed there, amid the dunes, a spaceship gone to ground.” Most historians might leave it there, satisfied that the weirdness of the geodesic dome will draw their readers in, but Lepore keeps going: “Chalk dusted their fingertips,” she writes. “Reams of perforated computer printouts unfurled across the floor.” Then, before telling us about why the company warrants a book-length study, we learn much more about the wives and children of the Simulmatics men:

The men wore bathing trunks and polo shirts and pondered punch cards; the women wore summer dresses and sandals and made potato salad and tuna salad and barbecue and macaroni salad and ham salad and pots of stew and piles of corn on the cob; their children—seventeen of them in all—waded in the ocean and built sandcastles, Camelots-by-the-sea, and sailed one-masted Sunfishes and chased a black poodle named Sputnik up and down the beach and over the creek. The children got so badly sunburned that at night their mothers doused them in vinegar to cool their skin: they smelled like pickles. On rainy days, they played Monopoly, hopscotching from Park Place to the B. & O. Railroad, collecting two hundred dollars every time they passed Go, and trying, as all monopolists must, to keep out of jail. The wives traded paperback copies of Peyton Place, a steamy novel about sex and female rebellion, its pages wilted from the humidity. And everything, and everyone, was covered with sand, as if, if they’d stayed there long enough, they’d have been buried, like ancient Egyptians.

Lepore’s shift of focus from the men of Simulmatics to the children and women seems at first like it might be mere “color,” superficial details that are only included to add texture to the main historical argument. In fact, the specifics allow her to reassert in form the underlying thesis of the book. Lepore wants us to see clearly that computational data can never absorb the granular reality of lived experience accurately. It always distorts.

Many of the people involved directly in Simulmatics suffered because of its obsessive pursuit of a pure world of data. Marriages ended, careers ran aground, ethics got compromised. But the canvas Lepore works with is far larger than just the company itself. Famous figures turn up left and right: Adlai Stevenson, Robert McNamara, Harold Laswell, Paul Lazarsfeld, JCR Licklider, Malcolm X, Richard Nixon, Daniel Ellsberg. The political scientist and writer Eugene Burdick, whose book The 480 provided a thinly veiled critique of Simulmatics in the aftermath of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, is just one of many clever inclusions. Lepore turns to science fiction, melodramatic films, and other detritus from popular culture as source material, lending her history a playful, absurdist tone, perfect for the era she examines. So too, Lepore uses Simulmatics effectively to present a wider angle on the history of the 1960s. She links the company’s obsessions with data to the Cuban Missile Crisis, anti-Vietnam War protests, urban riots, the violence at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the Watergate Scandal, and much more. Yet we always circle back, as in a novel, to the telling details, the ones that don’t easily compute. When Lepore turns to Simulmatics’ involvement in the Vietnam War, she borrows from Tim O’Brien’s famous short story collection, The Things They Carried, to relate numerous comparisons between what data scientists carried to their wartime research in Southeast Asia compared to what antiwar protesters took with them to big events such as the 1967 attempt to levitate the Pentagon.

For Lepore, Simulmatics provides a “cautionary tale, a timeworn fable” that goes way back into the past even as it serves as a harbinger of the future. As she eloquently puts it, “Prophesy is ancient, a species of mysticism. Prediction as a quantitative social science was new: outside of economics, social scientists had not, till then, generally made predictions.” Yet after World War II, the Department of Defense, the Ford Foundation, the new RAND think tank began to ask social scientists to make prediction the entire object of their research. These institutions called for scientists to claim knowledge—empirical, probabilistic, mathematical knowledge—of what would happen next. For Lepore, “This, however, was no less mystical than the ancient art of prophecy.” She points out that “the attempt to derive a general theory of the future rested on the presumption that human behavior can be predicted.” This was, “a presumption that, in turn, rested on the conviction that reckoning with people and societies and the human mind itself isn’t the stuff of poetry and paintings and philosophy but is, instead, the stuff of numbers and graphs and simulations.” The Ford Foundation called this new (to Lepore misguided) field “the behavioral sciences.” But what were they, really? The economist Kenneth Boulding, Lepore notes, remarked that the behavioral sciences were, in the end, anything “that gets money from the Ford Foundation.”

Prophesy and prediction are “ancient,” Lepore points out. They are also quite sensible in some quarters of knowledge such as the physical and natural sciences, engineering, efforts to stop climate change, astronomy, medical research, pharmacology, and public health. “But,” Lepore writes, “the study of the human condition is not the same as the study of the spread of viruses and the density of clouds and the movement of the stars.” This is because “human nature does not follow laws like the laws of gravity, and to believe it does is to take an oath to a new religion.” Worse yet, this sort of “predestination can be a dangerous gospel.” In more recent times, “the profit-motivated collection and use of data about human behavior, unregulated by any governmental body, has wreaked havoc on human societies, especially on the spheres in which Simulmatics engaged: politics, advertising, journalism, counterinsurgency, and race relations.” Moreover, “its rise also marked the near abandonment of humanistic knowledge.”

So far as Lepore is concerned, the dream of Simulmatics—to predict the future—also marked the beginning of a near abandonment of history. When a contemporary figure such as Silicon Valley engineer and self-driving car designer Anthony Levandowski recently declared that he did not “know why we study history” because to him “in technology, all that matters is tomorrow,” for Lepore he is dead wrong. Rather, as she shows in her book, “this cockeyed idea” itself “isn’t an original idea.” Actually, it is “a creaky, bankrupt Cold War idea, an exhausted and discredited idea…decades old, dilapidated.” The notion that history does not matter itself is history. The past is always around. It resists virtuality, simulation, digitization, easy algorithmic access, superficial statistical reduction, and, most of all, dismissal. Old ghosts lurk in the machine, messing up the seamless entry into a perfected future. Lepore notices that what seems new, shiny, and seemingly revolutionary in the present is often in fact stale, flawed, mistaken, even reactionary. This might also remind us of the converse as well. Things that may seem old, forgotten, antiquated—mere footnotes falling out the bottom of historical progress, details to be dismissed as noise in the data, ideas rejected because they do not fit well into a scheme of the future—are almost always worth remembering again, freshly, in all their obdurate complexity. That’s some augury sure to bug artificial intelligence, but it makes for quite exceptional intellectual history.

If Then’s conditional statement of a title also suggests one more thing: what now? For Lepore, if Simulmatics sought to translate the world into seamless, modular, computational data, then the many particular bits and bobs of information she uncovers about and around its story show us that the world simply does not work that way. It is stubbornly distinct, messy, buggy. It isn’t smooth or processed. It gets sand on it. It smells sour, like pickles. It lingers. The significance of Simulmatics as a company is that its hubris in the 1960s presaged the troubles of our own times. The era of big data, algorithmic logic, and predictive analytics we live in now has its own delusions of a world without grit. Lepore wants us to realize that the devil is in the details. Maybe the solutions could be too.

Notes[1] Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

[2] Stewart Brand, “Spacewar: Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums,” Rolling Stone, 7 December 1972. For Brand’s appreciation of Pool, see Stewart Brand, The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT (New York: Viking, 1987).

[3] Richard White, “New Yorker Nation,” Reviews in American History 47, 2 (2019): 159–67.

November 30, 2021

Rovings

Dwight Macdonald.Sounds“Dwight MacDonald on Film,” Unlocking the Airwaves: National Association of Educational Broadcasters (NAEB) CollectionMinus 5, Down With WilcoBig Thief, Change – EPBeck, Sea ChangeDark Woods Season 1Caetano Veloso, Meu CocoStanley Brothers,

Live in Seattle 1969

Scene on Radio, Season 5: The Repair1963 UCLA Folk Festival: Workshop: Folk Music Festival WorkshopBob Dylan, Live at the Beacon Theater, New York, 20 November 2021“Afterwords: Stuart Hall,” Sunday Feature, BBC Sounds“The Certificate,” BBC SoundsWordsAndrew Cornell, Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth CenturyKim Stanley Robinson, Three Californias Triology, Book 2: The Gold CoastAmitav Ghosh, Gun IslandGraham Greene, The Quiet AmericanJake Silverstein, “The 1619 Project and the Long Battle Over U.S. History,”

New York Times

, 9 November 2021Lara Feigel, “Inside story: the first pandemic novels have arrived, but are we ready for them,” The Guardian, 27 November 2021Walls and “Walls”

Underground Modernist: E. McKnight Kauffer

, Cooper HewittSurface is Only a Material Vehicle for Spirit, Kavi GuptaGlenn Kaino: In the Light of a Shadow MASS MoCA

A Designed Life: Contemporary American Textiles, Wallpapers and Containers & Packaging, 1951-1954,

Design Museum of ChicagoLakefront Anonymous: Chicago’s Unknown Art Gallery, 1100 FlorenceHannah Levy: Surplus Tension, Arts Club of ChicagoNancy Rubins: Sculpture & Drawing, Rhona Hoffman GalleryStages and “Stages”Out of Pocket Theater Company, A Picasso, MuCCCJody Stecher and Kate Brislin, Homegrown ConcertAndrew Rathbun Quartet, Constellation ChicagoScreensThe Beatles: Get BackGangs of London, Season 1Mayans MC, Season 3Narcos Mexico, Season 3Succession, Seasons 1 and 2Red Notice

Dwight Macdonald.Sounds“Dwight MacDonald on Film,” Unlocking the Airwaves: National Association of Educational Broadcasters (NAEB) CollectionMinus 5, Down With WilcoBig Thief, Change – EPBeck, Sea ChangeDark Woods Season 1Caetano Veloso, Meu CocoStanley Brothers,

Live in Seattle 1969

Scene on Radio, Season 5: The Repair1963 UCLA Folk Festival: Workshop: Folk Music Festival WorkshopBob Dylan, Live at the Beacon Theater, New York, 20 November 2021“Afterwords: Stuart Hall,” Sunday Feature, BBC Sounds“The Certificate,” BBC SoundsWordsAndrew Cornell, Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth CenturyKim Stanley Robinson, Three Californias Triology, Book 2: The Gold CoastAmitav Ghosh, Gun IslandGraham Greene, The Quiet AmericanJake Silverstein, “The 1619 Project and the Long Battle Over U.S. History,”

New York Times

, 9 November 2021Lara Feigel, “Inside story: the first pandemic novels have arrived, but are we ready for them,” The Guardian, 27 November 2021Walls and “Walls”

Underground Modernist: E. McKnight Kauffer

, Cooper HewittSurface is Only a Material Vehicle for Spirit, Kavi GuptaGlenn Kaino: In the Light of a Shadow MASS MoCA

A Designed Life: Contemporary American Textiles, Wallpapers and Containers & Packaging, 1951-1954,

Design Museum of ChicagoLakefront Anonymous: Chicago’s Unknown Art Gallery, 1100 FlorenceHannah Levy: Surplus Tension, Arts Club of ChicagoNancy Rubins: Sculpture & Drawing, Rhona Hoffman GalleryStages and “Stages”Out of Pocket Theater Company, A Picasso, MuCCCJody Stecher and Kate Brislin, Homegrown ConcertAndrew Rathbun Quartet, Constellation ChicagoScreensThe Beatles: Get BackGangs of London, Season 1Mayans MC, Season 3Narcos Mexico, Season 3Succession, Seasons 1 and 2Red Notice

SUNY Brockport Digital Public History Experiments

Joy and Happiness to All the Children of the World by the Russian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli on the campus of SUNY Brockport. Photo: Jazzersten.

Joy and Happiness to All the Children of the World by the Russian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli on the campus of SUNY Brockport. Photo: Jazzersten.This fall students students in my Honors 112: Reading and Writing Across Forms course at SUNY Brockport developed experimental digital public history projects. Each student documented a topic of interest from campus, community, regional, or state history. They researched the topic to develop a brief digital museum “label” for a photograph or sequence of multimedia documentation. They experimented with digital form using a WordPress website installed on a Reclaim webhosting account (thanks to SUNY Brockport for supporting this digital infrastructure!). You can view the projects at SUNY Brockport Digital Public History Project.

Students explored what it means to document the world, how to research its histories both well-known and hidden, and how one might curate their findings effectively through digital layout, clear writing, and an interplay of different kinds of documentation and explanation. What you will find is not a fully developed, completed project, but rather an entry point, a start, a first take by students, most of them in their first year of university. From histories of the SUNY Brockport campus itself to its sports programs, from local monuments and historical sites to nearby Rochester’s activist history to other dimensions of history in New York State, the projects reveal glimpses of public history and public life as students perceive them. Through combinations of direct observation, representational documentation, historical research, narrative description, analytic writing, digital design, and multimedia curation, the students begin to share the variety and richness of the social world, the built environment, and the lively history present all around us.

I lightly edited the post after a series of workshops and feedback to students on their projects. Students also drew upon the expertise of the librarians at SUNY Brockport’s Drake Memorial Library.

Visit the SUNY Brockport Digital Public History Project Experiments.