Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 24

April 2, 2022

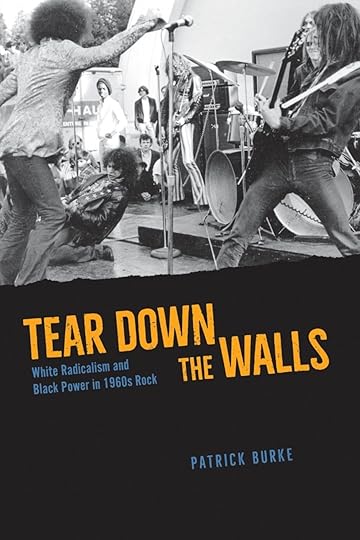

Soul By Proxy

Kramer_Burke-Tear-down-the-walls-white-radicalism-and-Black-Power-in-1960s-rock-book-review_The-Sixties_25-March-2022

Kramer_Burke-Tear-down-the-walls-white-radicalism-and-Black-Power-in-1960s-rock-book-review_The-Sixties_25-March-2022March 31, 2022

Rovings

Installation view, “Jamal Cyrus: The End of My Beginning” @ Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 05 February–29 May 2022. Photo: Jeff McLane/ICA LA.SoundsDaniel Lanois, “Jolie Louise”

Ukranian Village Voices

David Byrne, David Byrne Presents: ¡La Chiva Maravillosa! Colombia! Various Artists,

From the Lion Mountain: Traditional Music of Yeha, Ethiopia

The Go! Team, Sequences Part OneKronos Quartet, Sea Ranch SongsKronos Quartet, Folk SongsKronos Quartet, Michael Gordon: Clouded YellowLaurie Anderson and Kronos Quartet, LandfallJohn Aylward, Celestial Forms and StoriesJonathan Richman,

Cold Pizza & Other Hot Stuff EP

The Gobetweenies, BBC SoundsRamblings, BBC SoundsMarvel’s Wastelanders: Black WidowMarvel’s Wastelanders: HawkeyeMarvel’s Wastelanders: Star-LordMarvels

I Hear a New World: Early Electronics & Experimental Pop Music in Postwar Britain, 1957-1963,

Barbican Center

WordsMichael Almereyda and Robert Polito, eds., Manny Farber: Paintings and WritingsGordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957, ed. Sarah MeisterIngrid Monson, “The Problem with White Hipness: Race, Gender, and Cultural Conceptions in Jazz Historical Discourse,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 48, 3 (1995)Stephen Preskill, Education in Black and White: Myles Horton and the Highlander Center’s Vision for Social JusticeKim Ruehl, A Singing Army: Zilphia Horton and the Highlander Folk SchoolBrittany Spanos, “Rhiannon Giddens on Her ‘Lodestar’ Peggy Seeger,”

Rolling Stone,

7 March 2022Kathryn A. Ostrofsky, “Getting Primaried: The artificial way that ‘primary sources’ are packaged for history classrooms doesn’t help students make sense of the information they’re bombarded with in the real world,”

New American History

, 7 March 2022Johann N. Neem, “Walking Among the University’s Ruins,”

Public Books

, 8 March 2022Fred Turner, “Putting California Buddhism to Work in Silicon Valley,”

LARB

, 8 March 2022Anthony Molho and Gordon S. Wood, Imagined Histories: American Historians Interpret the PastCharles W. Mills, The Racial ContractKyle T Mays, An Afro-Indigenous history of the United StatesElizabeth Tandy Shermer, Indentured Students: How Government-Guaranteed Loans Left Generations Drowning in College DebtAndrew Preson, Outside In: the Transnational Circuitry of US HistoryDouglas Rossinow, Visions of Progress: The Left-Liberal Tradition in AmericaLara Leigh Kelland, Clio’s Foot Soldiers: Twentieth-Century US Social Movements and Collective MemoryLily Geismer, Don’t Blame Us: Suburban Liberals and the Transformation of the Democratic PartyNational Council on Public History, Organization of American Historians, American Association for State and Local History, “Reframing History”“Walls”

Isamu Noguchi A New Nature

@ White Cube

Takesada Matsutani: Combine

@ Hauser & Wirth

The New Bend

@ Hauser & WirthJennie C. Jones: Dynamics @ Guggenheim Museum

Jamal Cyrus: The End of My Beginning @

Institute of Contemporary Art

Bob Thompson: This House Is Mine

@ Smart Museum of ArtClaudette Schreuders: Doubles @ Jack Shaiman GalleryOxman Architects: Nature × Humanity @ SFMoMA

Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running

@ Jewish MuseumSurrealism Beyond Borders @ Tate ModernFluid Forms: A Review of Confluence @ Heaven GalleryMichael Heizer @ Gagosian

Beverly Buchanan: Shacks and Other Art

@ Edlin Gallery

All Together Now: Sound × Design

@ Chicago Museum of Design

Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities

@ Morgan LibraryWith Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art, 1972-1985, Hessel Museum of ArtThe Hidden Art: Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Self-Taught Artists from the Audrey B. Heckler Collection @ Folk Arts MuseumOne Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art @ The Museum of Contemporary Art“Stages”Macie Stewart and Lia Kohl @ Constellation Chicago, 19 February 2022 and @ McLean County Museum of History, Bloomington, IL, 26 February 2022Sequesterfest Vol 8 @ Experimental Sound Studio, 05 March 2022Post- & Nick Photinos @ Constellation Chicago, 06 March 2022Trap Door Theater, Occidental ExpressClarence and Roland White, “I Am A Pilgrim/Soldiers Joy,” Bob Baxter’s “Guitar Workshop,” 1973 This Is The Kit @ NPR Music Tiny Desk Concert, 17 December 2019Peggy Baker, Her Body as Words @ PlayBAC, 28 February-14 March 2022Sleater-Kinney, “Fortunate Son/Dig Me Out” @ Cat’s Cradle, Carrboro, NC, 26 May 2000Screens

Talking History: E. P. Thompson, C. L. R. James, and the Afterlives of Internationalism

Shintaro Miyazaki, “Counter-Algorhythmics as Prefigurative Dance of CommOnism,” Technoculture Research Workshop, SUNY BuffaloRoundtable Discussion of Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen’s Ideas That Made America @ Society for US Intellectual History Virtual Conference, 21 March 2022Murder on the Orient ExpressMurder on the NileThe French DispatchThe Book of Boba FettAndy Warhol’s Diaries

Run the Line: Retracing 43km of Hidden Railway

Installation view, “Jamal Cyrus: The End of My Beginning” @ Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 05 February–29 May 2022. Photo: Jeff McLane/ICA LA.SoundsDaniel Lanois, “Jolie Louise”

Ukranian Village Voices

David Byrne, David Byrne Presents: ¡La Chiva Maravillosa! Colombia! Various Artists,

From the Lion Mountain: Traditional Music of Yeha, Ethiopia

The Go! Team, Sequences Part OneKronos Quartet, Sea Ranch SongsKronos Quartet, Folk SongsKronos Quartet, Michael Gordon: Clouded YellowLaurie Anderson and Kronos Quartet, LandfallJohn Aylward, Celestial Forms and StoriesJonathan Richman,

Cold Pizza & Other Hot Stuff EP

The Gobetweenies, BBC SoundsRamblings, BBC SoundsMarvel’s Wastelanders: Black WidowMarvel’s Wastelanders: HawkeyeMarvel’s Wastelanders: Star-LordMarvels

I Hear a New World: Early Electronics & Experimental Pop Music in Postwar Britain, 1957-1963,

Barbican Center

WordsMichael Almereyda and Robert Polito, eds., Manny Farber: Paintings and WritingsGordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957, ed. Sarah MeisterIngrid Monson, “The Problem with White Hipness: Race, Gender, and Cultural Conceptions in Jazz Historical Discourse,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 48, 3 (1995)Stephen Preskill, Education in Black and White: Myles Horton and the Highlander Center’s Vision for Social JusticeKim Ruehl, A Singing Army: Zilphia Horton and the Highlander Folk SchoolBrittany Spanos, “Rhiannon Giddens on Her ‘Lodestar’ Peggy Seeger,”

Rolling Stone,

7 March 2022Kathryn A. Ostrofsky, “Getting Primaried: The artificial way that ‘primary sources’ are packaged for history classrooms doesn’t help students make sense of the information they’re bombarded with in the real world,”

New American History

, 7 March 2022Johann N. Neem, “Walking Among the University’s Ruins,”

Public Books

, 8 March 2022Fred Turner, “Putting California Buddhism to Work in Silicon Valley,”

LARB

, 8 March 2022Anthony Molho and Gordon S. Wood, Imagined Histories: American Historians Interpret the PastCharles W. Mills, The Racial ContractKyle T Mays, An Afro-Indigenous history of the United StatesElizabeth Tandy Shermer, Indentured Students: How Government-Guaranteed Loans Left Generations Drowning in College DebtAndrew Preson, Outside In: the Transnational Circuitry of US HistoryDouglas Rossinow, Visions of Progress: The Left-Liberal Tradition in AmericaLara Leigh Kelland, Clio’s Foot Soldiers: Twentieth-Century US Social Movements and Collective MemoryLily Geismer, Don’t Blame Us: Suburban Liberals and the Transformation of the Democratic PartyNational Council on Public History, Organization of American Historians, American Association for State and Local History, “Reframing History”“Walls”

Isamu Noguchi A New Nature

@ White Cube

Takesada Matsutani: Combine

@ Hauser & Wirth

The New Bend

@ Hauser & WirthJennie C. Jones: Dynamics @ Guggenheim Museum

Jamal Cyrus: The End of My Beginning @

Institute of Contemporary Art

Bob Thompson: This House Is Mine

@ Smart Museum of ArtClaudette Schreuders: Doubles @ Jack Shaiman GalleryOxman Architects: Nature × Humanity @ SFMoMA

Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running

@ Jewish MuseumSurrealism Beyond Borders @ Tate ModernFluid Forms: A Review of Confluence @ Heaven GalleryMichael Heizer @ Gagosian

Beverly Buchanan: Shacks and Other Art

@ Edlin Gallery

All Together Now: Sound × Design

@ Chicago Museum of Design

Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities

@ Morgan LibraryWith Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art, 1972-1985, Hessel Museum of ArtThe Hidden Art: Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Self-Taught Artists from the Audrey B. Heckler Collection @ Folk Arts MuseumOne Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art @ The Museum of Contemporary Art“Stages”Macie Stewart and Lia Kohl @ Constellation Chicago, 19 February 2022 and @ McLean County Museum of History, Bloomington, IL, 26 February 2022Sequesterfest Vol 8 @ Experimental Sound Studio, 05 March 2022Post- & Nick Photinos @ Constellation Chicago, 06 March 2022Trap Door Theater, Occidental ExpressClarence and Roland White, “I Am A Pilgrim/Soldiers Joy,” Bob Baxter’s “Guitar Workshop,” 1973 This Is The Kit @ NPR Music Tiny Desk Concert, 17 December 2019Peggy Baker, Her Body as Words @ PlayBAC, 28 February-14 March 2022Sleater-Kinney, “Fortunate Son/Dig Me Out” @ Cat’s Cradle, Carrboro, NC, 26 May 2000Screens

Talking History: E. P. Thompson, C. L. R. James, and the Afterlives of Internationalism

Shintaro Miyazaki, “Counter-Algorhythmics as Prefigurative Dance of CommOnism,” Technoculture Research Workshop, SUNY BuffaloRoundtable Discussion of Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen’s Ideas That Made America @ Society for US Intellectual History Virtual Conference, 21 March 2022Murder on the Orient ExpressMurder on the NileThe French DispatchThe Book of Boba FettAndy Warhol’s Diaries

Run the Line: Retracing 43km of Hidden Railway

March 17, 2022

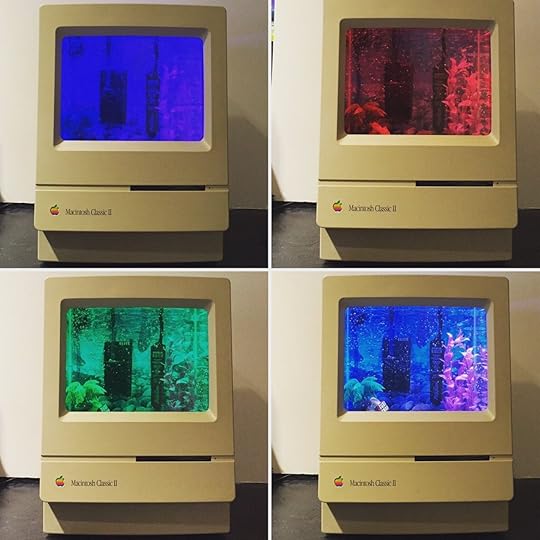

Defamiliarizing Digital History

Below is my contribution to Digital Cultural History: A Virtual Roundtable at the 2022 OAH Conference. Presenting ideas from my ongoing research on defamiliarization tactics for historical inquiry, my talk uses one example of image sonification to reflect upon how it can bring together cultural and digital history by using adventurous computational tactics to alert historians to aspects of form and content, information and context, buried in the empirical record as it is preserved in archives. Rather than turning people from the past into things, this approach strives to activate things so that we can more effectively glimpse (or in this case hear) the people caught up in artefactual and archival representations. Embracing distortion and iteration as paradoxical paths to greater accuracy in historical analysis, image sonification has the promise of inspiring a kind of synesthetic hermeneutics, a way of bringing together close and computational reading by disorienting the perceptual sensorium through human-computer interaction to better orient ourselves toward the past: its lives, forces, stories, structures, negotiations.

A 14-minute video takes the viewer/listener through one very brief, very tentative image sonification and what even this one preliminary experiment suggests for methods that might bend cultural and digital history together in more fruitful ways. Below the video is a script for those who wish to access the talk in that format. For additional readings, essays, and information about this research, see my webpage GlitchWorks: Digital Defamiliarization Tactics for Historical Inquiry.

Script — Defamiliarizing Digital HistoryMichael J. Kramer, Assistant Professor, Department of History, SUNY Brockport

“Oh, my God! People back home will just never believe this!” — Mance Lipscomb to photographer Matt Hinton when given print of the “silhouette” photo, according to Sam Hinton

[SLIDE]

We see the silhouette of Mance Lipscomb against the audience in the Hearst Greek Amphitheater at the 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. He’s playing an acoustic guitar in front of one microphone, with his hat placed carefully by his side. It’s a moment of cultural encounter as he performs for this predominantly white, middle-class, urban audience, encompassing issues of race, gender, class, and region. A male African-American musician and sharecropper from Navasota, Texas, Lipscomb was born to parents who lived through enslavement in the US South. Now in 1963, he takes his place center stage way out in California, on the campus of the state’s flagship university, in a structure funded by the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst and built in 1903 to signify the University of California at Berkeley’s claim at the turn of the twentieth century and thereafter that it was becoming a new bastion of democracy and wisdom, the so-called “Athens of the West.”

What did it mean for Mance Lipscomb to perform at the Greek on the Berkeley campus, at an institution that by 1963 was perhaps the preeminent public university in the nation, if not the world, a place of prize-winning scholars, top notch students, a place that ran the nuclear research program of the Cold War United States, among other things? This is very much a cultural historical question. Looking to material such as a photograph to try to address it is very much a cultural history move. Gaining currency in the historical profession during the 1980s and 90s, cultural history took social history’s efforts in the decades prior to study history from below, to broaden who counted as a historical actor and how, and applied them to a thing called culture. The term did double duty: the culture in cultural history stood for a turn to more aesthetic material, often non-textual, generated often by folkloric, popular, or mass entertainment people or institutions; culture also stood in for attention to value and belief systems, culture in the anthropological sense; and maybe even doing triple duty, culture pushed toward new methods of approaching the artefactual record, the archives, the empirical stuff or, for our purposes, the data or these data, through which we access the past as historians.

[SLIDE]

It is this last question of method that brings cultural history into contact with digital history, which has grown popular in many respects as a turn away from the cultural turn, a rejection of more semiotic, interpretive approaches of “reading” our historical data and a turn back to cliometrics, statistics, and a more positivist approach to the historical record. The so-called digital turn has often been placed by practitioners and critics alike as precisely a turn away from or even against the cultural turn.

To be sure, this is a simplification of the digital turn (and the cultural turn for that matter), but it’s a helpful and roughly accurate portrayal of the broad contours of these two fields as they have emerged. Yet I would contend that something has been lost in the false binary created between cultural and digital history. What has been lost is the question of how we might relate to historical inquiry what computer engineers call human-computer interaction, how we might think more critically about the ways in which human perception meets up with computational manipulation.

It’s not a choice between careful close reading by humans versus positivist, distant reading by computers. Rather, whatever scale one works at, whether one is looking at one artifact or many, whether one is pursuing network analysis, topic modeling, algorithmic approaches, or presenting digitized or born digital artifacts for shared inquiry through digital curation, cultural and digital history have the potential to come together in fruitful, even provocative, ways in service of more critically insightful (or as you’ll see, no, actually hear, in a moment, insoundful) understandings of the past and its peoples, its institutions, its issues, forces, and continued resonances in contemporary life.

[SLIDE]

Let us look again at the startling, expressive photograph of Mance Lipscomb at Berkeley in 1963. It was his second time appearing at the event, and the photograph is part of the over 10,000 photographs in the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive. The photograph is a visual glimpse at a sonic event, a silent rendering of one moment from the performative flow of a music concert. And it is of course already a technological creation, light captured on to film and then developed using chemical processes. Now that the photograph is digitized, it also carries in it not only the photographic technology that created it, but also the history of computer graphics software development, such as choices about how to translate it into digital data, compress it, and so on.

History here is highly mediated already. The artifact contains multitudes: a still image from a moving event; a silenced scene of sound being made; a glimpse out over the shoulder of a man whose audience is intently looking at and listening to him. Rather than only fight this mediation in the pursuit of some fantastical return to some pure present in the past, what if we embrace mediation and remediation as tactics of historical inquiry? What if we seek out ways of playing with the ductility of a digital image’s data in order to perceive what it represents in fresh, disorienting ways? By remixing, collaging, or transmediating the visual data into other outputs, for instance, we might even perceive as humans new information and aspects of what the image represents.

[SLIDE]

The image is silent, but what if by hacking existing software tools for historical interpretive ends, we turned its data into sound? To be clear, this does not mean we can magically recover the sounds being made when Lipscomb performed at Berkeley in 1963 from the image. We cannot, except perhaps in the most conjectural of senses if we took an archeological approach to the image’s venue and content, do so.

What we can do, though, is almost the opposite: not get back directly to the photograph’s content, but rather go forward, pay greater attention to its form through the ways that its digital data can be played, and played with, to produce new iterations of the artifact. Visual data can be outputted as sound so that we can ask strange, new questions, such as what does a photograph sound like?

Sounding out the visual data in the image of Lipscomb using Michel Rouzic’s Photosounder tool offers one very tentative experiment in this direction. I listened to the image’s pixel brightness from left to right using what sound engineers call pink noise. Now brace yourself: this really is a defamiliarization of the artifact as Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky imagined it in his 1917 essay “Art As Device,” sometimes translated as “Art As Technique.” Shklovsky wanted the defamiliarization tactic, in his words, “to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known…to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.” This sonification of image data that I did actually will go by really fast, and sound very disorienting, but notice how the pink noise quiets down right when we hit Lipscomb’s silhouette. This proved useful for me in using digital strategies to perceive something new about the cultural history of this particular artifact, this silent photograph of an intriguingly noisy cultural event out at the Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Here we go:

[PLAY SONIFICATION]

That is pretty far from Lipscomb’s beautiful blues playing and singing, but the disorientation and defamiliarization of the image, and of any audio recordings we have of Lipscomb from the time made in other settings, can still be quite productive. Even in this very strange rudimentary sonification of visual data, notice how it generates noise, then goes quiet as it passes over Lipscomb at the center of the photograph. The man making sound in the image is silenced here. This got me to thinking about how Lipscomb’s ability to move to the center of attention at Berkeley in 1963 was enabled, yet also somewhat undercut, by the ways in which he was a mysterious silhouette to many audience members. Defamiliarized himself from the rural community in which he typically played in Texas to this new audience in Berkeley, Lipscomb was in transit, at once linking together different strata of postwar American society yet also revealing the gap, the silences, between them.

The sonification defamiliarized the image, heightening my attention to the ways in which at the very same instance that Lipscomb appeared center stage, visible and appreciated, he was also rendered invisible. His knowledge was genuinely treated by the attendees at the Berkeley Folk Music Festival as equaling the worth of any of the institution’s most prestigious faculty members, yet Lipscomb’s own point of origin, his own experiences were also rendered somewhat silent, a rupture in the fabric of musical community in which he typically performed. Lipscomb becomes a kind of historical vortex here, bringing the silhouette of another cultural setting into a new light in the Greek Amphitheater on the Cal campus. In the photograph, he leaves a sort of hole punctured at the center of the proceedings.

All sorts of cultural negotiations of race, gender, class, and region are thus captured in this image. Even a strange sonification such as this one can help a historian suddenly perceive all of those negotiations more vividly in the photo by hearing their data play out on the sensorium. In a kind of synesthetic hermeneutics, sonification can alert the historian audially to things one only at first dimly sees in the visual artifact.

[SLIDE]

In this sense, defamiliarization tactics for historical inquiry such as sonification have the potential to address the danger of reproducing what Jessica Marie Johnson calls the “thingification” of people as data. Rather than treat lives as things, people reduced to dehumanized data, defamiliarization asks us to treat things as alive. Defamiliarizing an artifact can bring forward more boldly the traces of lived experiences in all their fraught negotiations of power, interaction, struggle, connection, alienation, pleasure, pain, joy, sadness. De-fetishizing the artifact as a thing by playing with the pliability of its existence as digital data, turning images into data correlated into sound compositions in this case, means being able to access what artifacts and archives represent: not a flattening of the archival record into things, but an activation of its things into heightened historical imaginings of the people, social forces, institutional dynamics, cultural encounters caught up in artefactual and archival representation.

Paradoxically, the futuristic computational distorting of the artifacts we study might allow us to get back more accurately to the pasts they preserve. Combining the cultural and digital history turns, bending them into each other, might enable us to read against the grain of the archive better by altering the very grain of the archive itself. Transforming image data into sonic correlations might quite literally, as well as figuratively, allow us to hear the silences of the archives, or at least tune our historical ears more effectively to the past in all its dimensions. Mance Lipscomb, and so too his audience at Berkeley, like all our ancestors, deserve nothing less.

[SLIDE Credits more info]

Photograph possibly taken by Matt Hinton. Preserved in the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive. For more information about the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, visit bfmf.net. For more information about defamiliarization research, visit michaeljkramer.net.

March 12, 2022

Sticking the Landing

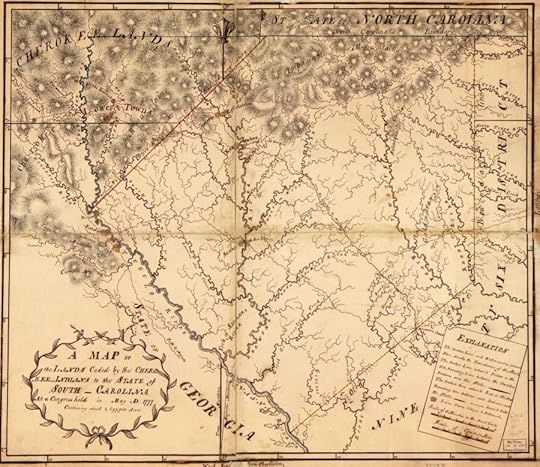

A Map of the lands ceded by the Cherokee Indians to the State of South-Carolina at a congress held in May, A.D. 1777; containing about 1,697,700 acres. ca. 1777. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

A Map of the lands ceded by the Cherokee Indians to the State of South-Carolina at a congress held in May, A.D. 1777; containing about 1,697,700 acres. ca. 1777. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.What do we really make of the rise of land acknowledgments in mainstream North American institutional settings? They have their origins in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights movements of 1970s Australia, and spread most prominently to Canada from there. By the late 2010s, arts venues, awards ceremonies, and the home pages of educational institutions in the United States were adopting them and they now increasingly appear even in corporate settings.

As speech acts, land acknowledgments are ambiguous, not exactly acts at all, and certainly not Acts, capital A, in the governmental or legal sense. They do not directly transform anything materially. They certainly do not redress historical injustices or suffering in any except the most cursory of ways. At best, currently, they are signifiers of uncollected debts, perhaps another kind of political “promissory note,” as Martin Luther King, Jr. called the US Declaration of Independence. They are heartfelt, they can even change consciousness by creating some friction and discomfort. These are not necessarily bad things, but they are not altering the situation on the ground, as it were.

This makes land acknowledgments sound innocuous; at their worst, however, they may be doing something quite troubling: land acknowledgments serve as confessions, they are spoken to release people from the sins of the past while changing nothing in the present or future. They are indulgences. The land acknowledgement becomes in fact a kind of disacknowledgment in disguise.

In this mode, the land acknowledgment becomes something like what Roland Barthes evocatively called “operation margarine.” Barthes noticed how whether in banal advertisements for margarine or much more serious forces of political and institutional power such as the military, the church, or the state, “a little ‘confessed’ evil saves one from acknowledging a lot of hidden evil.” Barthes’ essay is worth quoting more extensively for how effectively he identified the confounding ways in which acknowledgement becomes a disavowal:

One inoculates the public with a contingent evil to prevent or cure an essential one. To rebel against the inhumanity of the Established Order and its values, according to this way of thinking, is an illness which is common, natural, forgivable; one must not collide with it head-on, but rather exorcize it like a possession: the patient is made to give a representation of is illness, he is made familiar with the very appearance of his revolt, and this revolt disappears all the more surely since, once at a distance and the object of a gaze, the Established Order is no longer anything but a Manichaean compound and therefore inevitable, one which wins on both counts, and is therefore beneficial. The immanent evil of enslavement is redeemed by the transcendent good of religion, fatherland, the Church, etc. A little ‘confessed’ evil saves one from acknowledging a lot of hidden evil.

Confessions are more often for the confessor than anyone else. One wonders, have land acknowledgments emerged most of all for the easing of liberal guilt rather than as declarations or commitments to substantive political or legal transformation for indigenous peoples? After all, if we take land acknowledgments seriously, they propose extraordinary alterations in the political economy of the North American nation-state. They propose nothing less than its end, do they not? To acknowledge that the land was taken illegally and unjustly implies that it should be returned—all of it. Are those who make land acknowledgments ready to do this?

Probably not, but we should remember that any kind of “operation margarine” can backfire. The margarine melts. Inoculations open up new opportunities. Can the verbalized expressions of liberal guilt be harnessed for radical change? Or are they, as Barthes thought, just new, more oily deals, an artificial way for settlers to keep living off the fat of the land?

A deeper, more vexing question emerges too with the superficiality—or maybe even the tricky subterfuge—of land acknowledgments. Do they merely reproduce imperial, colonial, and capitalist ideas of property while purporting to combat them? This question has repercussions for indigenous peoples and settlers alike. After all, indigenous groups fought over lands and places long before Europeans and others arrived. This is no excuse to justify the continued practices of European imperialism into the present and future, to be clear, but it does raise the historical question: whose places are these really? How does one come by ownership of a place by the terms of today’s property rights discourse and practices? Can one belong to the land rather than it belong to them? Is there a different framework of place if we rethink the very meaning and assumptions of ownership and property?

If we treat place with “Western” notions of property rights, there is the opportunity for economic remedy, to be sure, and that could be a good thing, but is it also a devil’s bargain? In that the compensation itself reproduces the very ideological conditions of the exploitation. When land is imagined as owned rather than stewarded, does this merely renew the colonial project? Perhaps the more daring move would be to upend and dismantle the ideological assumptions about land, property, and place. For that, the intellectual history of indigenous ideas of place might prove to be as important as economic redistribution of lands within the existing system of exploitative property rights. Alongside alternative approaches to property, land, and place found in other traditions, even subversive ones from the European context, one might discover a truly transformative way forward. The goal is not to revert ownership, but instead to convert to a more sustainable and just future.

Let me acknowledge—irony noted—that there are many who have studied these questions far more deeply than me. They have grappled with these matters and come up with critiques, ideas, possibilities, ongoing dilemmas. Mine are just one observers’ speculations on the stakes of land acknowledgments, the ways in which they function, their implications, and their potential to do harm or good.

It may ultimately matter less what land acknowledgments achieve than what they initiate. If they are spoken as preface rather than culmination, they might become something less perfunctory, more disquieting, but only if they announce that something must come next. Alone, they do nothing but administer reproach without consequences, and might be doing more damage for that. If they signal in more profound ways that what’s past is prologue, they might get us somewhere.

What are those steps once acknowledgment occurs? That is a question into which we must not land, but leap.

March 9, 2022

2022 April 14—The Singer of Folk Songs

In the photograph, Sam Hinton—zoologist, oceanographer, illustrator, science museum director, and also songwriter, folk singer, and folk thinker—speaks of folk music tradition in the futuristic Pauley Ballroom at the University of California, Berkeley. Hinton is likely introducing Bessie Jones and the Georgia Sea Island Singers, the Greenbriar Boys, Jean Ritchie, and other featured performers at the December 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Sitting upright and attentive, front row center, is a familiar-looking beatnik. He listens intently to Hinton intently as Hinton perhaps draws on ideas from the previous day’s workshop “Learning to Sing Folk Songs—Tradition and Imitation,” held with esteemed folklorists Ralph Rinzler and Charles Seeger, and also building on Hinton’s ideas in his 1955 Western Folklore essay “The Singer of Folk Songs and His Conscience.” The young man is none other than aspiring folk/bluegrass musician Jerry Garcia. This and other newly discovered photographs of Garcia at the 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival ask us to revisit how the young musician absorbed ideas from the folk music revival, particularly what an “imitator” could do with traditions not his own. These ideas would stay with Garcia for the rest of his life and career. Taking in Hinton’s words, singing along with the Georgia Sea Island Singers at a “Fireside Sing,” hanging out with Rinzler, Ritchie, and other performers and attendees, Garcia encountered debates about what it meant to try to incorporate folk music styles into one’s very being rather than merely present them as antiquated museum specimens. Garcia’s Zelig-like presence at the 1962 Berkeley Folk Music Festival raises important questions about race, class, region, and authenticity as they moved through vernacular musical expression in the early 1960s, particularly in Atomic Age California; this helps us reconsider what a transmitter of tradition could be within the disorienting context of post-World War II America.

14 April 2022—The Singer of Folk Songs

In the photograph, Sam Hinton—zoologist, oceanographer, illustrator, science museum director, and also songwriter, folk singer, and folk thinker—speaks of folk music tradition in the futuristic Pauley Ballroom at the University of California, Berkeley. Hinton is likely introducing Bessie Jones and the Georgia Sea Island Singers, the Greenbriar Boys, Jean Ritchie, and other featured performers at the December 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Sitting upright and attentive, front row center, is a familiar-looking beatnik. He listens intently to Hinton intently as Hinton perhaps draws on ideas from the previous day’s workshop “Learning to Sing Folk Songs—Tradition and Imitation,” held with esteemed folklorists Ralph Rinzler and Charles Seeger, and also building on Hinton’s ideas in his 1955 Western Folklore essay “The Singer of Folk Songs and His Conscience.” The young man is none other than aspiring folk/bluegrass musician Jerry Garcia. This and other newly discovered photographs of Garcia at the 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival ask us to revisit how the young musician absorbed ideas from the folk music revival, particularly what an “imitator” could do with traditions not his own. These ideas would stay with Garcia for the rest of his life and career. Taking in Hinton’s words, singing along with the Georgia Sea Island Singers at a “Fireside Sing,” hanging out with Rinzler, Ritchie, and other performers and attendees, Garcia encountered debates about what it meant to try to incorporate folk music styles into one’s very being rather than merely present them as antiquated museum specimens. Garcia’s Zelig-like presence at the 1962 Berkeley Folk Music Festival raises important questions about race, class, region, and authenticity as they moved through vernacular musical expression in the early 1960s, particularly in Atomic Age California; this helps us reconsider what a transmitter of tradition could be within the disorienting context of post-World War II America.

14 April 2022—The Singer of Folk Songs: Jerry Garcia at the 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music

In the photograph, Sam Hinton—zoologist, oceanographer, illustrator, science museum director, and also songwriter, folk singer, and folk thinker—speaks of folk music tradition in the futuristic Pauley Ballroom at the University of California, Berkeley. Hinton is likely introducing Bessie Jones and the Georgia Sea Island Singers, the Greenbriar Boys, Jean Ritchie, and other featured performers at the December 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Sitting upright and attentive, front row center, is a familiar-looking beatnik. He listens intently to Hinton intently as Hinton perhaps draws on ideas from the previous day’s workshop “Learning to Sing Folk Songs—Tradition and Imitation,” held with esteemed folklorists Ralph Rinzler and Charles Seeger, and also building on Hinton’s ideas in his 1955 Western Folklore essay “The Singer of Folk Songs and His Conscience.” The young man is none other than aspiring folk/bluegrass musician Jerry Garcia. This and other newly discovered photographs of Garcia at the 1962 Winter Berkeley Folk Music Festival ask us to revisit how the young musician absorbed ideas from the folk music revival, particularly what an “imitator” could do with traditions not his own. These ideas would stay with Garcia for the rest of his life and career. Taking in Hinton’s words, singing along with the Georgia Sea Island Singers at a “Fireside Sing,” hanging out with Rinzler, Ritchie, and other performers and attendees, Garcia encountered debates about what it meant to try to incorporate folk music styles into one’s very being rather than merely present them as antiquated museum specimens. Garcia’s Zelig-like presence at the 1962 Berkeley Folk Music Festival raises important questions about race, class, region, and authenticity as they moved through vernacular musical expression in the early 1960s, particularly in Atomic Age California; this helps us reconsider what a transmitter of tradition could be within the disorienting context of post-World War II America.

2022 April 03—Digital Cultural History Virtual Roundtable

Now viewable with registration for the virtual part of the 2022 OAH Conference Website.

Digital history is typically associated with the use of statistical analysis at scale to address the macroscopic, cliometric, structural, and aggregate dimensions of history; cultural history more typically focuses on finely grained inquiries into micro-level topics through the use of close reading of artifacts, explorations of individual agency, and attention to theoretical intricacies of interpreting the past. Where do the two approaches meet, if they meet at all? This virtual roundtable presents five-minute videos from each panelist, focused on their research and its implications for bringing digital and cultural history together (or not), followed by a recorded Zoom conversation among the participants. Subsequent iterations of the roundtable after the conference will further develop the discussion, with additional examples, commentators, reflections, and findings.

ChairDr. Michael J. Kramer, Assistant Professor, Department of History, State University of New York-BrockportPanelistsLaura Brannan Fretwell and Janine Hubai, PhD Students, George Mason UniversityDr. Jessica Marie Johnson, Assistant Professor, Department of History, Johns Hopkins UniversityDr. Maria Cotera, Associate Professor, Mexican American and Latino Studies Department at the University of Texas, AustinDr. Lauren Tilton, Assistant Professor of Digital Humanities in the Department of Rhetoric & Communication Studies and Research Fellow in the Digital Scholarship Lab (DSL), University of RichmondDr. Scott Saul, Professor of English, University of California, BerkeleyDr. Michael J. Kramer, Assistant Professor, Department of History, State University of New York-Brockport (see video of talk, Defamiliarizing Digital History)03 April 2022—Digital Cultural History Virtual Roundtable

Digital history is typically associated with the use of statistical analysis at scale to address the macroscopic, cliometric, structural, and aggregate dimensions of history; cultural history more typically focuses on finely grained inquiries into micro-level topics through the use of close reading of artifacts, explorations of individual agency, and attention to theoretical intricacies of interpreting the past. Where do the two approaches meet, if they meet at all? This virtual roundtable presents five-minute videos from each panelist, focused on their research and its implications for bringing digital and cultural history together (or not), followed by a recorded Zoom conversation among the participants. Subsequent iterations of the roundtable after the conference will further develop the discussion, with additional examples, commentators, reflections, and findings.

ChairDr. Michael J. Kramer, Assistant Professor, Department of History, State University of New York-BrockportPanelistsLaura Brannan Fretwell and Janine Hubai, PhD Students, George Mason UniversityDr. Jessica Marie Johnson, Assistant Professor, Department of History, Johns Hopkins UniversityDr. Maria Cotera, Associate Professor, Mexican American and Latino Studies Department at the University of Texas, AustinDr. Lauren Tilton, Assistant Professor of Digital Humanities in the Department of Rhetoric & Communication Studies and Research Fellow in the Digital Scholarship Lab (DSL), University of RichmondDr. Scott Saul, Professor of English, University of California, BerkeleyMarch 6, 2022

Ideas of the PMC

X-posted from US Intellectual History Book Review.

Margaret O’Mara, The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of AmericaW. Patrick McCray, Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative CultureAlex Sayf Cummings, Brain Magnet: Research Triangle Park and the Idea of the Idea EconomyIn 1963, the President of the University of California, Clark Kerr, saw the future and thought it would be full of ideas. Or at least that it would be full of knowledge production. Kerr argued that “the production, distribution, and consumption of ‘knowledge’ in all its forms is said to account for 29 percent of gross national product…and ‘knowledge production’ is growing at about twice the rate of the rest of the economy.” The labor mediator-turned-higher-education-administrator believed that, “What the railroads did for the second half of the last century and the automobile for the first half of this century may be done for the second half of this century by the knowledge industry: that is, to serve as the focal point for national growth.” Writing at the height of postwar American power, as a booming economy and a spirit of consensus liberalism dominated, Kerr would soon face the ire of the very “knowledge workers” he sought to train. In places such as the University of California system, young New Leftists rejected his vision of them as widgets in the coming knowledge factory. Instead, those “bred in at least modern comfort” in the years after World War II, as the famous Port Huron Statement put it, saw all around them racism, sexism, alienation, and inequality as well as the escalating horrors of the war in Vietnam and the ever-present shadow of nuclear annihilation. Nonetheless, the notion of a postindustrial “knowledge economy” did not vanish. The idea that manipulating information, ideas, and research would replace the making of actual things as the key engine of economic growth persisted throughout the uncertain 1970s, it took off in the 1980s and 1990s, and right through the first decades of the twenty-first century, it has continued to loom large as the supposed future of American work and abundance.

The Americans laboring securely in Kerr’s new “knowledge industry” have taken many names and guises since the 1960s. They have been called white-collar workers, disruptive student radicals, later latte-drinking liberals, the upper middle class, yuppies, bobos in paradise, boomers (as if the entire postwar generation, no matter what their wealth or line of work, had been at the 1964 Free Speech Movement on Kerr’s University of California campus), Atari Democrats, New Democrats, Clintonites, Obama lovers, neoliberals, and the ten percent. Cultural critic Catherine Liu scathingly called them “virtue hoarders” in her recent polemic against them. In other contemporary squabbles on the left, these Americans were branded Warrenites rather than Bernie Bros. They were liberal professionals protecting who critics dismissed as ultimately more committed to protecting their own status than joining a new coalition of working Americans brought together in opposition to the elites in the “one percent.”

Who are these Americans working in the upper echelons of the knowledge economy, exactly? One of the best ways of understanding this amorphous but important class of Americans came from two veterans of the 1960s New Left, Barbara and John Ehrenreich. In a two-part 1977 essay published in Radical America, the Ehrenreichs argued that this group was a distinct, but distinct class: the Professional Managerial Class. The PMC, as they are now often called, came into existence in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They were not the old petty bourgeoisie of small-business proprietors and independent farmers, but a new class whose expertise was required to make an industrial economy function: engineers, scientists, teachers, doctors, social workers, functionaries, bureaucrats, and other professionals and managers who had the know-how to create and control the levers of the modern capitalist world. The PMC often sided with those above them on the economic ladder as their members pioneered more efficient means of expropriating surplus labor value from workers. Yet the PMC, the Ehrenreichs noted, were also workers themselves. Particularly as their numbers grew within the expanding knowledge industry after World War II, they became more and more like the rest of the working class, with whom they maintained important connections both structural and cultural.

A powerful group in both their importance to the emerging knowledge economy and their deeply ambiguous positioning within American capitalism, the PMC created norms that now dominate the nation’s sense of itself. Professional training, expertise, education, credentialization, technical acumen, and an ideal of meritocratic advancement (usually more fiction than actuality)—this is now the vision of how to get ahead and stay ahead in the United States. The PMC also, as Barbara Ehrenreich would later write, possesses an intense “fear of falling” from their class position. As Clark Kerr imagined they would in 1963, the PMC has played a crucial role in shaping American culture and politics, but perhaps not in the ways he expected. Instead of happily working in the knowledge factory of the coming information society and information economy, the PMC has instead remained a confusing and unstable force in American life, pushing forward what Alex Sayf Cummings cleverly calls the “idea of the idea economy,” what W. Patrick McCray names as a “creative culture,” and Margaret O’Mara simply describes as “the remaking of America.” These three historians do not take up the theory of the Professional Managerial Class explicitly—O’Mara focuses on the political economy of Silicon Valley, McCray combines the history of technology with the sociology of art to tell the tale of the Technology-and-Art movement, and Cummings investigates Research Triangle Park in North Carolina as an unexpected origin point for today’s knowledge economy—but each in her or his own way also tracks the rise of the PMC. Together, their books reveal something important: Cummings, McCray, and O’Mara all notice how close-knit networks have shaped the nature of PMC membership. The knowledge economy expanded, but the Professional Managerial Class actually remained quite constrained, with access to it fraught. In Margaret O’Mara’s political and business history of Silicon Valley, we realize that even in this most celebrated of locations, where tech was supposedly revolutionizing everything and a New Economy had emerged on the Information Superhighway, the on-ramps were few and far between. Instead, a tight circle of venture capitalists, engineers, and programmers consolidated power rather than spreading it to a broader populace. McCray examines collaborations between elite avant-garde artists and postwar engineers; these eccentric, edgy connections across disciplinary divides yielded strange and wonderful art, yet ultimately the dream of breaking through to radical reimaginings of technological society led back only to the existing economic imperatives of commerce and industry. In Cummings’ book on Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, the story of the PMC takes a Southern twist, and the new knowledge factory sometimes looks as much like an update to the old paternalistic Southern mill town as it does like a bold new vision of the New South and the information age. In these books, we see again and again the PMC flicker into view: both its dream of realizing a more rationalized, meritocratic, and flourishing postindustrial civilization for the many often and its often-hypocritical role providing technicians for implementing ever more barbaric form of capitalist exploitation and immiseration.

In the Shadow of the Valley—Margaret O’Mara’s The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of AmericaO’Mara’s book is worth starting with because she examines one of the most important places, both materially and symbolically, for the rise of the PMC within the emergence of the knowledge economy. She seeks to understand what made Silicon Valley distinctive, to define what one might call a sort of Santa Clara Valley exceptionalism. The prevailing myth is that the Valley grew out of an embrace of libertarian freeness, of countercultural experimentation melded with geeky research know-how. Against this boosterism, many have noted that federal government defense spending largely funded Silicon Valley’s rise to prominence. O’Mara splits the difference. In her history, “it is neither a big-government story nor a free-market one: it’s both.” She contends that the largesse of Cold War defense spending combined with a tight circle of engineers and financiers to push forward the business success of the region. As she writes, “This book is about how we got to that world eaten by software. It’s the seven-decade-long tale of how one verdant little valley in California cracked the code for business success, repeatedly defying premature obituaries to spawn one generation of tech after another….” At the same time, O’Mara shows how Silicon Valley’s story is not just a local one to Northern California. It is also, she claims, a “history of modern American” as a whole. In her study, Silicon Valley cannot be understood without tracing its links to old-money financial firms and companies back East or to the development of extensive Defense Department spending and intensive lobbying efforts in Washington DC. For O’Mara, the key insight is that “the Valley’s tale is one of entrepreneurship and government, new and old economies, far-thinking engineers and the many non-technical thousands who made their innovation possible.”

Within her story we keep seeing how local and national (and sometimes international) factors intersected to shape a political economy conducive to generating favorable business conditions for those in control of Silicon Valley. Here we visit the upper echelons of the PMC, where their interests (and some of the figures themselves) really were outright capitalists and not an ambiguous upper middle class or managers. O’Mara notes that much of the seed money for the earliest tech companies came not just from the federal government, or from Stanford University, but also from existing economic interests. Venture capitalists such as Arthur Rock, soon to become titans of the region, used the profits from IBM stocks to fund new chipmakers and computer companies in the 1950s. “The firms origins underscored how tightly wedded the Valley was to outside, old-economy interests from the very start,” O’Mara concludes. Companies such as Hewlett Packard succeeded in this context and the close ties between a small group of venture capitalists, company owners, lawyers, and politicians would keep Silicon Valley going through subsequent waves of invention and development as well as challenges and difficulties. Even as things got more countercultural in the 1970s, O’Mara shows time and time again how the culture and politics of a small network retained control.

Yet, as Silicon Valley developed within the so-called military-industrial complex, a new and far larger group of engineers, managers, and professionals began to dominate the region, supported primarily by Defense Department contracts. “By the end of the 1950s,” O’Mara explains, “tens of thousands of engineers streamed daily into Lockheed’s doors in their white shirts and narrow ties, working on cutting-edge technologies so top secret that they couldn’t tell their families over the dinner table what they did at work that day. Nearby suburbs filled with Lockheed men and their wives and children, further skewing the Valley’s demographics toward the white, the middle class, and the college educated.” Here was the PMC of the 1950s. Roughly a decade later, their children began to come of age, lending the Silicon Valley PMC a more colorful, radical, hippie-ish flavor, but one, she contends, that was not that different in key respects. “Blending the change-the-world politics of the counterculture with the technophilic optimism of the Space Age,” these new Silicon Valley workers were “a steadily enlarging techno-tribe that emerged in the Bay Area and other college towns and aerospace hubs at the turn of the 1970s.” That said, according to O’Mara, “the gulf between the scientific Cold Warriors and the techno-utopians was not as great as it seemed.” Younger countercultural technologists may have embraced more libertarian lifestyles and even, at times, liberal and even radical politics, but they nonetheless maintained a deep faith in technology and capitalism as the best ways forward. Their hair was longer, their clothing more colorful, and their ideas zanier, but in the end, they sought to maintain their PMC status. They thought, as some in Silicon Valley liked to say, to try to do good while also doing well, impervious to the contradictions between the two.

Whether wearing a white collar or a tie-dyed t-shirt, the workers of Silicon Valley embraced the new managerial styles of the postwar era. The “HP way” at Hewlett Packard encouraged loose rules and creativity, setting the precedent for subsequent firms. If these were knowledge factories, they were not like the factories of old. Instead, Silicon Valley companies “blended the organizational chart of the twentieth-century corporation with the personal sensibilities of the nineteenth-century sole proprietorship,” O’Mara writes, which is a nice way of describing the PMC labor ideal. More crucially, while younger Silicon Valley programmers and engineers stayed up late playing video games and inventing new kinds of human-computer interactions at infamous places such as Xerox PARC, those calling the shots began to lobby and fight in California and Washington DC for low taxes and lax regulation. From local bars such as Walker’s Wagon Wheel in Mountain View, they extended the PMC approach into the halls of power and influence in the California legislature and eventually in Congress and the White House. “The horizontal networks of Silicon Valley,” O’Mara explains, became “a webbing of firm and VC, lawyer and marketer, journalist and Wagon Wheel barstool.”

Some of this mode of PMC social organizing, O’Mara proposes, even got baked into the tech itself, particularly in the shaping of the World Wide Web. For instance, Larry Page’s algorithm for Google’s search engine may have started in the peer review process of the academy, but she contends that “his circle of links also called to mind the ecosystem of the Valley.” As O’Mara convincingly points out, “Those most connected were the post powerful; credibility and reputation came from knowing others in the network.” The social formations of Silicon Valley shaped the technology it developed, which in turn now shapes the social formations of how we search and sort information, people, culture, value, and more in the technology at the center of the knowledge economy.

O’Mara also notices that a key part of Silicon Valley’s “code” for success has been its labor practices. Tech firms adopted loose managerial tactics partly to keep out unionization. The staunchly pro-capitalist, anti-labor position of company owners allowed them to make common cause with everyone from Ronald Reagan and Newt Gingrich to the new “Atari Democrats” of the Valley itself. The PMC as a class thrived in Northern California because of the ambiguous boundaries these work norms created between those at the top and those just below them. Stock options, open offices, flexible hours, acceptance of eccentricity, and the encouragement of individual initiative kept employees in line. Yet in recent years, engineers, programmers, and other employees have nonetheless begun to shift their views on their working conditions. “Keeping the networks tight and personal,” as O’Mara puts it, led to sexual harassment and racial inequities as well as increasingly alienating labor practices. Even as manufacturing itself moved overseas from the Santa Clara Valley, maybe the New Left protesters against Kerr had been right all along: the sparkling corporate campuses of the San Francisco Peninsula were becoming dark, Satanic mills after all. Knowledge factories after all are still factories.

Engineering Art—W. Patrick McCray’s Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative CultureIn Making Art Work, W. Patrick McCray shifts the story from O’Mara’s focus on the political and business history of Silicon Valley to the experimental collaborations between avant-garde artists and corporation-employed engineers in the 1960s and thereafter. He argues that these experiments set the stage for today’s “creative classes,” so celebrated as they are by recent urban studies theorists such as Richard Florida. While art historians have long explored the objects these artist and engineers produced together, few have used close archival examination of their “activities,” as McCray calls them. Familiar characters from art history such as Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, the Judson Church contemporary dance choreographers, and other luminaries of the 1960s avant-garde New York art scene appear, but we also learn much more about the curators and engineers who joined in—colorful characters such as Frank J. Malina with his Leonardo journal, Gyorgy Kepes, and two key shapers of the art-and-technology experiments, Johan Wilhelm “Billy” Klüver with his Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) and Maurice Tuchman, curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and director of its Art and Technology Program. We also learn much more about the engineers who arrived from places such as Bell Labs (where Klüver worked for a time) to help artists bring their visions to fruition. At events such as the 1966’s 9 Evenings at the 69th Street Armory in New York (originally planned for Stockholm Festival of Art and Technology) and later efforts, the focus turned to all kinds of out-of-focus experiments that might access the strange new potential of technological life. Artists, working with engineers, wired up bodies for electronics, worked with telephony and closed-circuit televisions to create dizzying experiential environments, sought to evoke Space-Age, cybernetic, ambient settings of interactivity between people and machines, and even created fake weather—an artificially generated fog at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan.

Their work was eccentric, but it looped back to the high stakes of labor in the knowledge economy. The key place where someone such as Billy Klüver and his Experiments in Art and Technology program found a home, for instance, was in the labor mediator Theodore W. Kheel’s “Automation House,” founded in 1967 in New York City by the American Foundation on Automation and Unemployment as a center for the study of working conditions in the age of increasingly automated modes of industrial production. Avant-garde artists and their collaborating engineers may have seemed utterly different, but they found commonality in the question of their labor and the framework of anxieties about automation of it. As members of the PMC, they seemed capable of possibly identifying downward socioeconomically rather than upward, of using artistic collaboration and community to forge a new vision of the knowledge economy and American life within it.

McCray has a fine eye for the ironies of the cross-disciplinary work in which these artists and engineers engaged. Artists, by and large, wanted to be more engineers, conducting research and learning how to become “managers of technological processes,” while engineers sought to infuse their work with more artistic eccentricity. For artists, McCray believes, the curiosity about working with engineers “was partly a desire to work with new and often unavailable technologies. Added to this was a sense of crisis about the relevance of commodifiable, object-oriented art made using traditional media in a rapidly changing art world.” Engineers, meanwhile, “faced mounting attacks about their complicity in the arms race, environmental destruction, and other global ills.” Therefore, “the art-and-technology movement presented an opportunity to humanize technology and redefine their profession.” The artists wanted to be engineers, the engineers artists. Both wanted to redefine what a PMC-dominated society might look and be like.

What one notices most of all in McCray’s study is the restlessness of artists and engineers keen to push past the constraints imposed by institutions upon their labor and its outputs. Organized as different from each other, artist and engineers who participated in the art movement McCray documents discovered that they had much in common. They both longed to push their professional work into domains not quite conquerable by corporate and capitalist forces. Here was a nascent kind of PMC resistance, efforts to get wilder and more outlandish in expending resources on processes of collaboration rather than products that could be clearly and immediately commodifiable. Rather than point to ways of making more money, they produced artworks that sought, as art can do, to hold up a mirror to society.

This was quite literally the case when it came to Robert Whitman’s work with engineers at Bell Labs and Philco-Ford: they constructed mirror systems that enveloped viewers in experiences of “gentle narcissism” by projecting hologram-like images that appeared to blur the boundaries between the real and the illusory, the material and the dematerialized. Here was an effort to speak to the PMC’s vision of itself as immersed in the new postindustrial world, where technology served to advance individual efforts at self-actualization. It was the kind of approach criticized a few years later by Christopher Lasch as the PMC’s “culture of narcissism,” but it also had a populist slant, aimed at the masses as well as elites. The Art and Technology Movement of the 1960s and 70s, at least as McCray portrays it, sought to reach the everyman as much as those who would later be able to attend Burning Man, but by the 1990s its legacy of daring interdisciplinary exploration had nonetheless been thoroughly reintegrated into corporate America. At Nicholas Negroponte’s MIT Media Lab and elsewhere on campuses as well as in countless tech companies, the goal was not to enable PMC workers to push out from technology into artmaking, but rather to bring the benefits of artmaking with technology into the corporation. Art shifted from the possibilities of the prophetic to the necessities of making profits. Richard Florida’s “creative classes” had arrived. The more idiosyncratic experimentation of McCray’s “creative culture” was largely a thing of the past.

Triangulations—Alex Sayf Cummings’s Brain Magnet: Research Triangle Park and the Idea of the Idea EconomyMcCray documents a world gone by, yet the intellectual labor and creativity of the PMC continues to be a crucial aspect of the knowledge factory, the information society, or, as Alex Sayf Cummings playfully puts it, “idea of the idea economy.” Her book focuses on the rise of “cognitive capitalism,” but not in Silicon Valley or the elite artworlds of New York, Los Angeles, and Art Expos; rather, Cummings turns to a seemingly unlikely place: the pine forests of the Piedmont in North Carolina between Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill. There, a group of boosters began to envision a postindustrial economy in the hinterlands. In a place of mill towns, textile factories, and furniture factories as well as the lasting legacies of slavery and Jim Crow, academics, politicians, local business owners imagined that a place devoid of manufacturing—except for the manufacturing of ideas—could be built.

The place they brought into being would prove so successful that many now refer to the region simply as “the Triangle,” named after the place they managed to create: Research Triangle Park, often shortened to RPT. Cummings uses RTP to document how a “new political economy” of creativity and ideas “was part of a concerted cultural project, one that explicitly valued certain types of labor and industries—and, by extension, certain kinds of people—as more important than others.” In Research Triangle Park, we glimpse the rise of the postwar PMC with a Southern twist.

Later in Cummings book, she tells us about a sign along a road in Research Triangle Park on which someone has graffitied a kind of vernacular slogan, “We think a lot.” The question of intellectual labor—its value yet its oddly policed boundaries—returns again and again in this fascinating study. She writes, “”RTP and the Research Triangle as a whole offer an early and crucial example of a development strategy based specifically on leveraging intellectual and cultural resources—such as universities and the arts—to present an attractive image of a place to live for an emerging class of scientific and technical workers. Indeed, the aim was not merely to create an image of a place but to invent an entire place itself….” While this top-down imagining and creating of RTP could, as Cummings smartly notes, resemble nothing less than an updating of the paternalistic mill towns that populated the South during the height of industrial America, nonetheless they demanded the recruitment and support of a new class of professionals and managers. “RTP was a place expressly designed for knowledge workers before that term was even introduced,” she explains. “It was green, pastoral, sprawling, quiet, clean—everything that a traditional city was not. It was a landscape modeled on a college campus, thought to be an ideal place for thinkers to think.” In fact, “Nothing was accidental or organic…. The park’s planners and boosters not only created a template of what an environment for intellectual labor ought to look like.” In doing so, “they also pioneered an approach to economic development that leveraged creativity, culture, and especially universities to attract advanced industries and educated workers.” For Cummings, it is “in RTP, not Silicon Valley” where “one finds a conscious and deliberate effort to build an information economy.” Here, she argues, away from the big cities and centers of financial and cultural power, we can better see how “the rise of this cognitive capitalism has been too little recognized by scholars and policy makers” as something made rather than inevitable. Whether in the early vision of a kind of open office at the modernist Burroughs Wellcome building or in the recruitment of scientists who were refugees from East European communism or in the triumphant landing (for RTP’s boosters) of an IBM research office, federal government divisions focused on environmental research, and, in 1977, the National Humanities Center, RTP became a fantastical vision—and then a dramatic realization—of the Professional Managerial Class’s labor and lifestyle as part of the knowledge economy.

Nowhere does this appear more vividly than in the rise of the software company SAS under the watchful eye of its libertarian-minded manager Jim Goodnight. Goodnight left an alienating engineering position at General Electric’s facility connected to the US space program in Florida to work in academia at NC State and then found his own company. “In his career,” Cummings contends, “we see a glimmer of the yearnings that later gave rise to the flexible work culture of the creative class, who might be unencumbered by the constraints of traditional factory, office, or retail workers but who also put in time around the clock.” Goodnight created a workplace of perks, from childcare and artists-in-residence programs to flexible labor conditions to company recreational clubs, in order to recruit and retain workers. He became a latter-day Southern factory owner, with his own mansion quite literally adjoining SAS’s corporate campus. Only now the product whose production he oversaw was dematerialized. It was knowledge, research, analytics, consulting services, software. For Cummings, the shirtless dudes playing ultimate frisbee on SAS’s pastoral corporate campus may have seemed new, but really they were just the latest incarnation of the managerial functionaries hired to keep things going at the Southern site of production. From “the chemistry PhDs” in the earliest days of RTP during the 1950s and early 1960s, to the “hip software engineers” who began to arrive in the 1970s, the members of the PMC took up their job in the updated factory of a deindustrialized economy. They may have looked different over time, but to Cummings “in terms of education and cultural capital—as well as their role as sought-after residents, workers, and taxpayers—whether it is 1965 or 2005” they shared much in common. As she puts it, “The tastes simply changed,” but the arrangements of class and capital remained much the same.

The PMC at RTP brought many good things to North Carolina—a new tax base, a sense of being at the cutting-edge of modern American economic and cultural developments, and even limited success in overcoming Jim Crow segregation between middle-class black and white populations. Nonetheless, for Cummings, the success of RTP’s “pastoral capitalism,” as the architect Louise A. Mozingo calls it, remains quite fraught. “The knowledge economy,” Cummings writes, “continues to be an elitist formula for development and growth—one that occludes many in pursuit of the interests of the most educated and credentialed among us.” In response to these shortcomings, Cummings makes a daring call to expand who gets to count as creative, as full of ideas. “If the future is only a playground for the affluent and educated, an endless multiplication of the manicured lawns of SAS or the whisky bars of downtown Durham, who gets in and who gets left out?” she asks, compellingly arguing that “surely everyone is creative in their everyday lives in ways big, medium, and small.” Therefore, “If we favor an economy dedicated to the idea of ideas, we would benefit from a far more capacious notion of what creativity and innovation really mean.” RTP helped the PMC come to North Carolina, but only newer and more expansive conceptualizations of “the idea of the idea economy” will overcome its shortcomings in realizing a more just and egalitarian South—or America as a whole for that matter.

ConclusionThese three books tell cautionary tales about the PMC, but they also suggest something else: that beyond a narrow and exclusive definition of the PMC is perhaps the possibility for a different kind of knowledge economy, one that functions for the masses rather than just the upper classes. Much as the Ehrenreichs were suspicious of the PMC’s elitism and their members’ anxieties about falling downward in status and power, the two theorists nonetheless held out hope for the potential of the PMC to side one day with those below them. The Ehrenreichs did not fully abandon the idea that a broad-based coalition might emerge from the shared structural conditions of working for wages within the knowledge economy. In the studies of O’Mara, McCray, and Cummings, we glimpse both sides of the PMC: their failure by and large to deploy expertise in service of something more than capitalist exploitation, yet also their continual push to remake America in a new way, to imagine a more creative culture, to honor the idea of the idea economy as an expansive rather than a limited concept. In these three books, a more transformative mental picture of professionalism lurks within the stupid historical realities of the knowledge economy that the PMC has managed to produce.