Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 23

May 26, 2022

History Unwired

The new HBO show We Own This City, from David Simon and George Pelecanos, tells a fictionalized version of the corrupt Gun Trace Task Force in Baltimore. It might be understood as a sequel to their famed HBO series The Wire. Many of the same actors reappear in new roles, and the drug war and the police in Baltimore returns as the focus. Yet the original show felt as though it was out ahead of history. We Own This City, by contrast, feels like it is just desperately trying to keep up with history. The Wire spread the word televisually from the corner to those beyond it about topics such as the actual state of urban America, policing, the richness of Afro-Baltimorean life despite the challenges of poverty and racism, and the interconnected stories of many people, marginalized and elite, in this fabulous but troubled city. We Own This City feels as if it is in pursuit of historical forces that might, in fact, have overtaken it. Fictionalization served the social realism of The Wire well; the realities of a dysfunctional society seem to have trumped fiction on We Own This City.

This is not meant to be a criticism; it almost seems to be purposeful in the show’s presentation. In the back-and-forth temporal concept for the show, there is a sense of dislocation. Where are we in time exactly? Then, now, when? Freddie Gray’s 2015 death at the hands of police and the subsequent protests against that incident hang over the show, but they are in the background of what we witness on screen. Instead, we are thrown about offices, crime scenes, police units, street corners, bars and restaurants, scenes from the past remembered during interviews, and more current discussions and dialogues among characters. The repeating set piece of police database entries in difficult to understand code, used as a kind of scene cut, also makes for a mood of always being a little behind the action. Wait, one asks, what is being entered here? Whose computer is this? Are these the datafied codes of the coverup or are they the traces of investigatory inquiry into that coverup?

All of the show comes to the viewer in a stark digital-feeling cinematography of hyper-reality that adds to the sense of a show out of breath as it attempts to keep up with the unbelievable real-world plot that has outpaced fiction. The show’s camerawork takes on a kind of raw, viral, social media video quality to it while still echoing something of the surveillance edge of The Wire. It’s as if who is watching who has changed, spiraled out of control from the way in which The Wire structured spectatorship. On The Wire, which culminated in the meta-commentary of the final season’s focus on journalism coverage, the viewer was on the outside, but continually invited in to the human stories and systemic conundrums of Baltimore. On We Own This City, we are swallowed up by history.

Even the characters placed closer to the viewer—investigators, passerby, honest cops—seem trapped, unable to escape. The wire on The Wire surveilled, but it also gave us distance, a feeling that we could see the larger structural problems, the way everything connected. We Own This City abandons this conceit. Sure there are still wires and tracking devices and perspectives meant to be outside the thick of the corruption, but overall, it is as if the clarity of relationality glimpsed on The Wire has vanished into far more confusing complicities, alienations, and despondencies. The Wire was bleak, but retained enormous hope as well; We Own This City feels far more disconsolate.

The Wire hummed. It shared with the wider world the staggering beauty of people trying their best under almost impossible circumstances. The system was broken with occasional moments when it worked. Life was not good overall, but life went on. There was a cycle, a way forward. The sytem was far from perfect, it contained tragedy and trauma, but it comedy and hope also permeated through moments of connection, pride, insistence on kinship, and efforts to do better. The world of Baltimore on The Wire was flawed, but it could move forward, reproducing itself in all its ugly with some of the good still included.

The overall effect of We Own This City is more like a puzzled grunt of vexation at the state of things. It feels more as if we are poised at the end of a broken system that needs complete replacement. You see this in the off-the-hinge, cartoonish character of Sergeant Wayne Jenkins, hammed up to the hilt by actor Jon Bernthal. You glimpse it in the affect of exasperation and exhaustion expressed best perhaps in the acting of Wunmi Mosaku as Nicole Steele, a civil-rights-division attorney, and Jamie Hector, reincarnated from the cold-blooded drug kingpin Marlo Stanfield into the principled Bunk-like homicide detective Sean Suiter, a man trying to be good police in a department that has lost its way. In the past, the small and large failures and triumphs of these types of characters made a difference. On We Own This City, the jury is out. We aren’t so sure.

Returning to the scene of the crime in the Baltimore of The Wire, We Own This City proposes that something is unfixable with policing in the United States—if it ever was fixable in the first place. Yet the reasons why, and more crucially how to solve the problem, recede not into the past, but oddly into the future, unattainable. On The Wire, the feeling was that despite everything maybe we could turn the corner on the mistaken “war on drugs” in the United States and all its sordid history; We Own This City suggests that the history unleashed by that war may own us.

May 15, 2022

Emissaries From Woodstock Nation

I really enjoyed talking with Jesse Jarnow, host of the Good Ol’ Grateful Deadcast podcast, about the Grateful Dead arriving on their Europe ’72 tour as emissaries of “Woodstock Nation,” helping to establish what I call, in The Republic of Rock: Music and the Sixties Counterculture (Oxford University Press, 2013), the Woodstock Transnational. We discuss this at about one hour and forty minutes in to the “Netherlands ’72” episode, but the whole season and indeed the whole podcast is worth a listen whether you are a Deadhead or just curious.

May 9, 2022

Digitizing the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive

Some reflections from me on working on this project with Nicole and Northwestern University Libraries:

Project manager Nicole Finzer and many others did such incredible work digitizing the Berkeley Folk Music Festival’s 30,000-plus artifacts through an NEH Access and Preservation Grant over the last few years.

A bit of background. Northwestern University Libraries purchased the archive from Festival Director Barry Olivier in 1973. Then the collection just sat there for the most part, largely unprocessed until archivist Sigrid Perry told me about it one day in 2010 when I was conducting research in NUL’s Special Collections room. Eventually, preservationists, vendors (the staff at Backstage Library Works), digital librarians, catalogers, archivists, programmers, student interns, even a few participants in the original festival, which took place between 1958 and 1970, all contributed to the digitization of the entire collection.

The digitization of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive serves as a reminder of the enormous labor and resources required to bring a digitization and digital history project to fruition. Don’t forget: it’s worth it! These projects expand access and analysis of the past. They also expand communities of learning and knowledge, interaction and connection in the present.

That said, we should not minimize what it takes to get these projects up and running in terms of commitment and collaboration. From the NEH grant itself, written by Northwestern librarian Carolyn Caizzi with assistance from me and others, to additional labor and funding at Northwestern University Libraries, the Berkeley Folk Music Festival’s digitization required far more than just a day or two of scanning. Far more! It took unanticipated preservation and preparation of artifacts; strategizing about cataloging and metadata; generating many new NACO (Name Authority Cooperative Program) records; testing and improving the development of Northwestern University Libararies’ digital repository system; and other tasks.

In this sense, these projects are not about scholars magically making projects appear from thin air, but rather groups of experts with different skills coming together to prepare and curate a rich, multifaceted set of materials for public exploration. The projects also seem to work best when they benefit the partners. The Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive digitization was not merely completed through the library functioning as service and the scholar participating as client or customer. Rather, even as the digitization helped me continue to develop the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project as a digital public history effort, Northwestern University Libraries was able to use the project to test and improve their in-house digital repository system. I was able to continue teaching with the archive after my adjunct professorship ended at Northwestern; NUL was able to figure out how its departments might work together effectively, how to train students interested in library and archive work, and how to work through the challenges of such a large digitization effort.

These projects take institutional commitment. They take collaboration. They take good communication among people with different kinds of expertise. They need extraordinarily capable project managers such as Nicole. And they take all of us keeping an eye on how the project might benefit all the partners. There are always tensions, but at their best, projects such as this one harness a range of labor and knowledge in respectful ways to generate a community of making, learning, thinking, listening, and creating that even comes to include those from the past who are gone but whose lives live on in the artifacts themselves. We remember them by studying what they left behind. Their expertise becomes part of the project too.

Also, while they require people from a range of backgrounds, with a disparate set of skills and expertise, maybe what’s most intriguing about archival digitization and digital public history as collaborative endeavors is that they encourage participants to reach across assumed boundaries of knowledge. Everyone should not “stay in their lane,” as the phrase goes. Rather, these sorts of projects have the potential to become truly interdisciplinary. In this case, I as a historian learned so much about what goes into digitization, and continue to take part in improving the catalog metadata so that searches and other uses of the digital repository can become more effective. Meanwhile, Nicole and fellow digitizers became nothing short of practicing historians. As they went through the material, they noticed crucial, sometimes troubling details that demanded interpretation, such as the discrepancy that emerged in the business records between the pay for female as compared to male performers at the Berkeley Festival. The historian was now contributing to the library and archival work; the librarians and archivists were now thinking historically.

In this way, the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive’s digitization became a kind of ensemble effort in which we each played the instruments we were best at playing but also found ourselves trading notes, learning new approaches, creating a song larger than any one person’s contribution—a festive tune, full of dissonances and harmonies, produced from the collective effort.

Nicole Finzer on the Digitization of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive

Some reflections from me on working on this project with Nicole and Northwestern University Libraries:

Project manager Nicole Finzer and many others did such incredible work digitizing the Berkeley Folk Music Festival’s 30,000-plus artifacts through an NEH Access and Preservation Grant over the last few years.

A bit of background. Northwestern University Libraries purchased the archive from Festival Director Barry Olivier in 1973. Then the collection just sat there for the most part, largely unprocessed until archivist Sigrid Perry told me about it one day in 2010 when I was conducting research in NUL’s Special Collections room. Eventually, preservationists, vendors (the staff at Backstage Library Works), digital librarians, catalogers, archivists, programmers, student interns, even a few participants in the original festival, which took place between 1958 and 1970, all contributed to the digitization of the entire collection.

The digitization of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive serves as a reminder of the enormous labor and resources required to bring a digitization and digital history project to fruition. Don’t forget: it’s worth it! That said, we should not minimize what it takes to get these projects up and running in terms of commitment and collaboration. From the NEH grant itself, written by Northwestern librarian Carolyn Caizzi with assistance from me and others, to additional labor and funding at Northwestern University Libraries, the Berkeley Folk Music Festival’s digitization required far more than just a day or two of scanning. Far more! It took unanticipated preservation and preparation of artifacts; strategizing about cataloging and metadata; generating many new NACO (Name Authority Cooperative Program) records; testing and improving the development of Northwestern University Libararies’ digital repository system; and other tasks.

In this sense, these projects are not about scholars magically making projects appear from thin air, but rather groups of experts with different skills coming together to prepare and curate a rich, multifaceted set of materials for public exploration. The projects also seem to work best when they benefit the partners. The Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive digitization was not merely completed through the library functioning as service and the scholar participating as client or customer. Rather, even as the digitization helped me continue to develop the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project as a digital public history effort, Northwestern University Libraries was able to use the project to test and improve their in-house digital repository system. I was able to continue teaching with the archive after my adjunct professorship ended at Northwestern; NUL was able to figure out how its departments might work together effectively, how to train students interested in library and archive work, and how to work through the challenges of such a large digitization effort.

These projects take institutional commitment. They take collaboration. They take good communication among people with different kinds of expertise. They need extraordinarily capable project managers such as Nicole. And they take all of us keeping an eye on how the project might benefit all the partners. There are always tensions, but at their best, projects such as this one harness a range of labor and knowledge in respectful ways to generate a community of making, learning, thinking, listening, and creating that even comes to include those from the past who are gone but whose lives live on in the artifacts themselves. We remember them by studying what they left behind. Their expertise becomes part of the project too.

Also, while they require people from a range of backgrounds, with a disparate set of skills and expertise, maybe what’s most intriguing about archival digitization and digital public history as collaborative endeavors is that they encourage participants to reach across assumed boundaries of knowledge. Everyone should not “stay in their lane,” as the phrase goes. Rather, these sorts of projects have the potential to become truly interdiciplinary. In this case, I as a historian learned so much about what goes into digitization, and continue to take part in improving the catalog metadata so that searches and other uses of the digital repository can become more effective. Meanwhile, Nicole and fellow digitizers became nothing short of practicing historians. As they went through the material, they noticed crucial, sometimes troubling details that demanded interpretation, such as the discrepancy that emerged in the business records between the pay for female as compared to male performers at the Berkeley Festival. The historian now was contributing to the library and archival work; the librarians and archivists were now thinking historically.

In this way, the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive’s digitization became a kind of ensemble effort in which we each played the instruments we were best at playing but also found ourselves trading notes, learning new approaches, creating a song larger than any one person’s contribution—a festive tune, full of dissonances and harmonies, produced from the collective effort.

May 8, 2022

Who Really Won the Cold War?

East German border guards look through a fallen section of the Berlin Wall, 11 November 1989. Photo: AP/Lionel Cironneau.

East German border guards look through a fallen section of the Berlin Wall, 11 November 1989. Photo: AP/Lionel Cironneau.For the first few decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, it seemed undeniable to argue that the United States won the Cold War. The demise of the Soviet Union and its satellite states, even the post-Tiananmen Square Chinese turn toward capitalism suggested we were witnessing the “end of history,” as Francis Fukuyama infamously argued. All the future would hold would be the stable establishment of liberal market-based global society in perpetuity. Or maybe the opposite was true and we were “watching the world wake up from history,” as the British band Jesus Jones sang at the time. Either way, the United States and its system looked to be triumphant.

Yet looking back from the vantage point of 2022, maybe we had it all wrong. Maybe what happened was not the spread of Western-style corporate-liberal democracy, but rather the seepage out into the rest of the world of what had previously been contained in the degenerated and deformed workers’ states of the Eastern Bloc. When the wall came down and the Iron Curtain parted, it wasn’t liberal democracy flooding in, but rather faux-socialist oligarchy leaking out.

To be sure, one could easily ask “what liberal democracy?” when thinking about in the West during the Cold War, and not be entirely wrong, but that’s a another topic for another time. For now, the focus might be placed on what we have seen in the United States and around the world since the 1990s. Has it really been the expansion of democracy? Maybe more accurately, we have witnessed thirty-plus years of extraordinary challenges to it. Let us review. Right away in the early 1990s the Balkan conflict erupted, with its ghosts surfacing of sectarian and ethnic conflict dating back to World War II if not centuries before that. Genocides in African countries took place and wars fought for the most part over control of raw resources for export to Western capitalist industries. The abysmal failure of the peace accords between Israel and Palestine occurred. The continued worldwide inability to confront the human causes of climate change are a constant theme since 1989, as are the privileging of profits over human rights by and large.

Even the George W. Bush administration’s post-9/11 calls for war in the very name of freedom and democracy rang false and right from the start seemed sometimes to be nothing more than shrill cries to cover up corrupt business deals, the expansion of the military-industrial complex, and control of oil reserves. Eventually, it gave rise not to democracy, but rather to torture and war crimes committed by representatives of the US. In Afghanistan, the US eventually lost the war itself and the very forces of authoritarian rule that it invaded the country to overthrow returned to power.

In the aftermath of Bush’s War on Terror (or was it but the continuation by the Obama administration?), various color revolutions and an Arab Spring seemed to be upswells of democratic longings. Yet none lasted beyond temporary blossomings of upheaval. And some, as in Syria, merely saw enormous destruction and even more extreme consolidations of power once again by the very forces of authoritarianism being fought in the first place (crucially, one should note, thanks to intensive Russian support).

Who really won the Cold War then? It starts to look like a far more open question than we generally assume.

Meanwhile, in the US itself there has been the steady infiltration of Russian influence in US politics, particularly in what can only be called the takeover of the Republican Party through strategic lobbying and fundraising during the last decade or so. From John McCain’s 2008 campaign to Donald Trump’s election in 2016 right up to the very present, it is as if not one, but many Manchurian Candidates are now in play within domestic American politics.

Meanwhile, momentary outbursts of protest such as Occupy Wall Street or Black Lives Matter or the Me Too movement were by and large coopted and quelled by centrist Democrats and corporations keen to bail out banks and keep the existing economic and political system in place rather than support bottom-up pushes for expanded democracy. Efforts to transform health care into a public good such as Obamacare, while significant and important, were largely structured around maintaining private profits (recall that the individual mandate approach of the Affordable Healthcare Act began as a proposal from the conservative Heritage Foundation to counter calls for single-payer health insurance).

Since the 2010 midterm election and even more so since the 2016 election of Donald Trump, the anti-democratic strategies of the right have greatly intensified and accelerated, from refusals to seat judges in Republican-controlled Congresses to efforts to gerrymander local voting districts in anti-democratic ways to propaganda campaigns that heighten fear to rulings issued by the courts, right up to the Supreme Court, that undercut the expansion of democracy or, more crucially, redefine democracy as a facade for authoritarianism. At this point, ideas once considered beyond the pale when it comes to American democracy, the protection of voting and civil rights, and the unacceptable scapegoating of those deemed to have different or vulnerable identities or positions in society—these have all become commonplace.

At what point does the three-decade gathering storm of these anti-democratic forces require us to rethink assumptions about 1989 and the American victory in the Cold War? The lurking presence of Russia around the world in locations such as Syria or now Ukraine as well as the deep penetration of Russian interests in domestic politics of the United States makes one wonder: at what point do we pay more attention to the fallout rather than the fall of the Berlin Wall, the repercussions rather than the original supposed strike for freedom? The US seemed to win the Cold War, but perhaps as time passes, it starts to look more clearly like a Pyrrhic victory. Citizens of formerly communist states got blue jeans and Scorpions’ “Wind of Change,” but more than that they got what in the end was the consolidation of power by the very oligarchic forces that had ruled prior to the end of communism. Americans and their allies in the Cold War find themselves tilting ever more intensely toward authoritarian movements with expressly anti-democratic goals, often with connections back to Russia.

That’s more and more what the world looks like today, isn’t it? So maybe the West did not win the Cold War, after all. Maybe after the meltdown of the Soviet Union and its satellite countries, what was left was not a fresh beginning but the putrid remains, the rot of festering wounds. Defeat was not defeat at all, but rather a different kind of victory: not history’s end or history waking up, but its steady plodding failure to live up to the promise of democracy. Maybe that it what now be confronted both historiographically and in the present moment of ever-growing crisis.

April 30, 2022

Rovings

Adam McEwen: Execute, Gagosian.SoundsTony Renaissance, “Ice Blue,” We Stand With UkraineLea Bertucci: Trespassing, Roulette Tapes PodcastVinny Golia: Scaling Up, Roulette Tapes PodcastMiguel Frasconi: Breaking Glass, Roulette Tapes PodcastImmanuel Wilkins: Make It Shine, Roulette Tapes PodcastBjork, “Human Behavior”

Tinariwen, Radio Tisdas/Amassakoul Influences (Mixtape), Aquarium Drunkard

Elvis Costello, All This Useless BeautyFreakons, FreakonsChristopher Trapani, Horizontal DriftMack McCormick, A Treasury Of Field Recordings and The Unexpurgated Folk Songs of Men: Treasury Of Field Recordings Vol. 1 & 2

Anna Tivel, “Illinois”

Klaus Wachsmann, Uganda Collection

“Poor Boy Blues” Variations,

Old Weird America

Mystery Jazz Acetate from Sanders Recording Studio on W. 48th St.

Emily Pick,

The Wire Adventures in Sound,

April 2022

Bas Jan, “You Have Bewitched Me”Cheri Knight, “Prime Numbers”Words

Kevin Dan, “A Hall of Mirrors: Cabala, Spiegel Der Kunst Und Natur, In Alchymia (1615),”

Public Domain Review

, 15 March 2022

Matt Mehlan, “Archive Dive: Fred Anderson Collection,”

Experimental Sound Studio

Newsletter, 23 March 2022

Nella Larsen,

Passing,

BBC Sounds

Lawrence Schenbeck, Racial Uplift and American Music, 1878-1943Marvin Edward McAllister, Whiting up: Whiteface Minstrels & Stage Europeans in African American Performance

Charlie Post, “Beyond Racial Capitalism: Toward a Unified Theory of Capitalism and Racial Oppression,”

Brooklyn Rail,

October 2020

Satnam Virdee, “The

Longue Durée

of Racialized Capitalism: A Response to Charlie Post,”

Brooklyn Rail

, February 2021

Charlie Post, “A Response to Satnam Virdee’s The Longue Durée of Racialized Capitalism,”

Brooklyn Rail

, February 2021

Edward McClelland, “This is the End of Chicago (Geographically),”

Chicago Magazine,

13 April 2022

Edward McClelland, “A Trip to Hegewisch, Chicago’s Most Remote Neighborhood,”

Chicago Magazine,

25 January 2022

David Yaffe, “‘I was born here and I’ll die here, against my will’: Time Out of Mind at 25,”

Trouble Man: Musings of David Yaffe,

28 April 2022

TM Brown, “Hidden in a Fire Island House, the Soundtrack of Love and Loss,” New York Times, 29 April 2022Merve Emre, “The Act of Persuasion,” New York Review of Books, 21 April 2022“Walls”

Adam McEwen: Execute, Gagosian

Igshaan Adams: Desire Lines

, Art Institute of Chicago

Barbara Stauffacher Solomon: Exists Exist

,

Graham FoundationAlex Katz: Ada, Gladstone GalleryYinka Shonibare CBE RA: Planets in My Head, Frederik Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park

Mixpantli: Contemporary Echoes

, LACHMA

Modern Art

, LACMA

City of Cinema: Paris 1850–1907

, LACMA

The Wende Museum of the Cold War

Larry Bell, Dia: BeaconJeff Wall, White Cube Mason’s YardHulda Guzmán: Meet Me in The Forest, Stephen Friedman GalleryJuan Araujo: Laughing and the Storm, Stephen Friedman GalleryRivane Neuenschwander: Trôpego Trópico, Stephen Friedman GalleryField Guide to North American Happiness, Paintings by Francis Zaander, Eat Paint Studio“Stages”

Laurie Amat and Kristina Warren,

Monosound/Sympraxis

, TQC 2022, Experimental Sound Studio

Dancers on Film: Maya Deren in Context, Getty Research Institute

Hot off the Presses: The Human Being in American Art: A Transatlantic Book Launch, Center for Ideas & Society, UC Riverside

Gary Gerstle on

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era

, Washington History Seminar, Wilson Center, National History Center, 11 April 2022

Screens

Possibly in Michigan

by Cecelia Condit (1983, US, 12 min.) and

The Amateurist

by Miranda July (1998, US, 14 min.), Walker Arts Center

website

The Lost DaughterMurder on the Orient Express (2017)Slow Horses, Season 01Billions, Season 06Despite the Falling SnowAll the Old KnivesMoon Knight, Season 01Tokyo Vice, Season 01

Adam McEwen: Execute, Gagosian.SoundsTony Renaissance, “Ice Blue,” We Stand With UkraineLea Bertucci: Trespassing, Roulette Tapes PodcastVinny Golia: Scaling Up, Roulette Tapes PodcastMiguel Frasconi: Breaking Glass, Roulette Tapes PodcastImmanuel Wilkins: Make It Shine, Roulette Tapes PodcastBjork, “Human Behavior”

Tinariwen, Radio Tisdas/Amassakoul Influences (Mixtape), Aquarium Drunkard

Elvis Costello, All This Useless BeautyFreakons, FreakonsChristopher Trapani, Horizontal DriftMack McCormick, A Treasury Of Field Recordings and The Unexpurgated Folk Songs of Men: Treasury Of Field Recordings Vol. 1 & 2

Anna Tivel, “Illinois”

Klaus Wachsmann, Uganda Collection

“Poor Boy Blues” Variations,

Old Weird America

Mystery Jazz Acetate from Sanders Recording Studio on W. 48th St.

Emily Pick,

The Wire Adventures in Sound,

April 2022

Bas Jan, “You Have Bewitched Me”Cheri Knight, “Prime Numbers”Words

Kevin Dan, “A Hall of Mirrors: Cabala, Spiegel Der Kunst Und Natur, In Alchymia (1615),”

Public Domain Review

, 15 March 2022

Matt Mehlan, “Archive Dive: Fred Anderson Collection,”

Experimental Sound Studio

Newsletter, 23 March 2022

Nella Larsen,

Passing,

BBC Sounds

Lawrence Schenbeck, Racial Uplift and American Music, 1878-1943Marvin Edward McAllister, Whiting up: Whiteface Minstrels & Stage Europeans in African American Performance

Charlie Post, “Beyond Racial Capitalism: Toward a Unified Theory of Capitalism and Racial Oppression,”

Brooklyn Rail,

October 2020

Satnam Virdee, “The

Longue Durée

of Racialized Capitalism: A Response to Charlie Post,”

Brooklyn Rail

, February 2021

Charlie Post, “A Response to Satnam Virdee’s The Longue Durée of Racialized Capitalism,”

Brooklyn Rail

, February 2021

Edward McClelland, “This is the End of Chicago (Geographically),”

Chicago Magazine,

13 April 2022

Edward McClelland, “A Trip to Hegewisch, Chicago’s Most Remote Neighborhood,”

Chicago Magazine,

25 January 2022

David Yaffe, “‘I was born here and I’ll die here, against my will’: Time Out of Mind at 25,”

Trouble Man: Musings of David Yaffe,

28 April 2022

TM Brown, “Hidden in a Fire Island House, the Soundtrack of Love and Loss,” New York Times, 29 April 2022Merve Emre, “The Act of Persuasion,” New York Review of Books, 21 April 2022“Walls”

Adam McEwen: Execute, Gagosian

Igshaan Adams: Desire Lines

, Art Institute of Chicago

Barbara Stauffacher Solomon: Exists Exist

,

Graham FoundationAlex Katz: Ada, Gladstone GalleryYinka Shonibare CBE RA: Planets in My Head, Frederik Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park

Mixpantli: Contemporary Echoes

, LACHMA

Modern Art

, LACMA

City of Cinema: Paris 1850–1907

, LACMA

The Wende Museum of the Cold War

Larry Bell, Dia: BeaconJeff Wall, White Cube Mason’s YardHulda Guzmán: Meet Me in The Forest, Stephen Friedman GalleryJuan Araujo: Laughing and the Storm, Stephen Friedman GalleryRivane Neuenschwander: Trôpego Trópico, Stephen Friedman GalleryField Guide to North American Happiness, Paintings by Francis Zaander, Eat Paint Studio“Stages”

Laurie Amat and Kristina Warren,

Monosound/Sympraxis

, TQC 2022, Experimental Sound Studio

Dancers on Film: Maya Deren in Context, Getty Research Institute

Hot off the Presses: The Human Being in American Art: A Transatlantic Book Launch, Center for Ideas & Society, UC Riverside

Gary Gerstle on

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era

, Washington History Seminar, Wilson Center, National History Center, 11 April 2022

Screens

Possibly in Michigan

by Cecelia Condit (1983, US, 12 min.) and

The Amateurist

by Miranda July (1998, US, 14 min.), Walker Arts Center

website

The Lost DaughterMurder on the Orient Express (2017)Slow Horses, Season 01Billions, Season 06Despite the Falling SnowAll the Old KnivesMoon Knight, Season 01Tokyo Vice, Season 01

April 25, 2022

2022 May 02—Folk Music Data, Or, The Celestial Monochord and the Global Jukebox

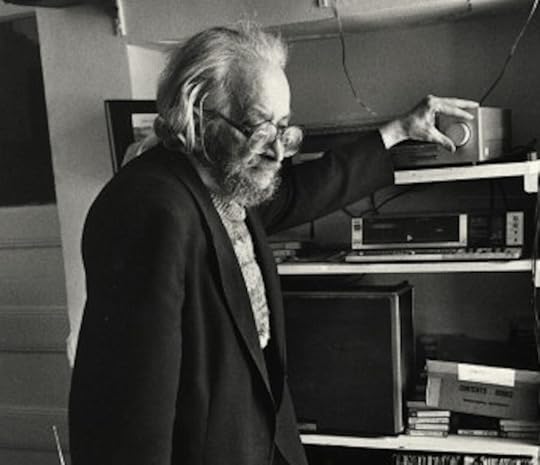

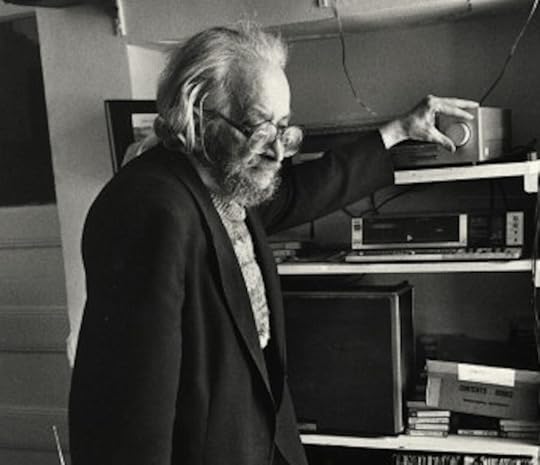

Harry Smith.

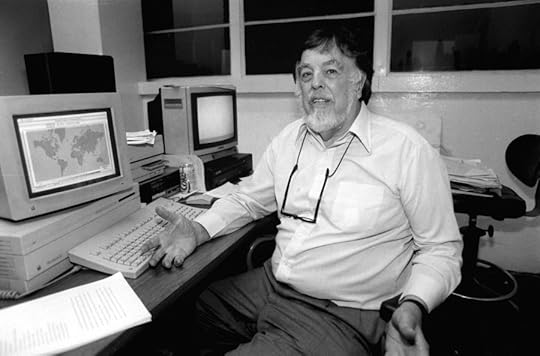

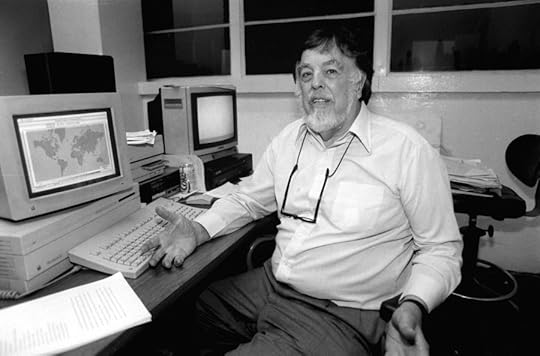

Harry Smith. Alan Lomax.

Alan Lomax.“It’s a way of programming the mind,” the artist, collector, and compiler of the 1952 Folkways Anthology of American Folk Music Harry Smith once remarked of his alchemical methods for rearranging cultural ephemera into patterned forms. Even though Smith did not use a computer, he believed his technique turned material into, as he put it, “a punch card of a sort” for the mind to process. The relationship of Smith’s artistic practice to computation and information theory during the 1950s and 60s invites more attention than it has previously been given. Another figure from the folk music world, the folklorist Alan Lomax, provides a valuable comparison to Smith. Working in roughly the same time period as Smith, Lomax actually did use computers extensively in his folk music research when he embarked on a multi-decade project beginning in the late 1950s through which he sought to categorize and analyze global song performance styles statistically. Smith imagined “programming the mind” as if it were a punch card. Lomax quite literally fed punch cards through an IBM mainframe to process the data of folk song for what he called his “cantometric” system. How each figure investigated folk music as data is suggestive of a “computational imagination” that spread far beyond the emergent computer industry itself in the United States during the years after World War II. Moreover, the quandaries they faced in trying to handle music as fragmented bits (and bytes) of data resonate with vexing contemporary dilemmas of treating culture and human expression computationally. From issues of race, class, gender, and region to the question of how to approach the technological sublime when it comes to large scales of data and cultural complexity, Smith and Lomax offer us ways of better understanding both the postwar era and today’s digital era.

2022 May 02—Folk Music Data Sublimes

Harry Smith.

Harry Smith. Alan Lomax.

Alan Lomax.“It’s a way of programming the mind,” the artist, collector, and compiler of the 1952 Folkways Anthology of American Folk Music Harry Smith once remarked of his alchemical methods for rearranging cultural ephemera into patterned forms. Even though Smith did not use a computer, he believed his technique turned material into, as he put it, “a punch card of a sort” for the mind to process. The relationship of Smith’s artistic practice to computation and information theory during the 1950s and 60s invites more attention than it has previously been given. Another figure from the folk music world, the folklorist Alan Lomax, provides a valuable comparison to Smith. Working in roughly the same time period as Smith, Lomax actually did use computers extensively in his folk music research when he embarked on a multi-decade project beginning in the late 1950s through which he sought to categorize and analyze global song performance styles statistically. Smith imagined “programming the mind” as if it were a punch card. Lomax quite literally fed punch cards through an IBM mainframe to process the data of folk song for what he called his “cantometric” system. How each figure investigated folk music as data is suggestive of a “computational imagination” that spread far beyond the emergent computer industry itself in the United States during the years after World War II. Moreover, the quandaries they faced in trying to handle music as fragmented bits (and bytes) of data resonate with vexing contemporary dilemmas of treating culture and human expression computationally. From issues of race, class, gender, and region to the question of how to approach the technological sublime when it comes to large scales of data and cultural complexity, Smith and Lomax offer us ways of better understanding both the postwar era and today’s digital era.

April 10, 2022

Digital Cultural History—A Virtual Roundtable

Digital history is typically associated with the use of statistical analysis at scale to address the macroscopic, cliometric, structural, and aggregate dimensions of history; cultural history more typically focuses on finely grained inquiries into micro-level topics through the use of close reading of artifacts, explorations of individual agency, and attention to theoretical intricacies of interpreting the past. Where do the two approaches meet, if they meet at all? This virtual roundtable presents five-minute videos from each panelist, focused on their research and its implications for bringing digital and cultural history together (or not), followed by a recorded Zoom conversation among the participants. Subsequent iterations of the roundtable after the conference will further develop the discussion, with additional examples, commentators, reflections, and findings.

ChairDr. Michael J. Kramer, Assistant Professor, Department of History, State University of New York-BrockportPanelistsLaura Brannan Fretwell and Janine Hubai, PhD Students, George Mason UniversityDr. Jessica Marie Johnson, Assistant Professor, Department of History, Johns Hopkins UniversityDr. Maria Cotera, Associate Professor, Mexican American and Latino Studies Department at the University of Texas, AustinDr. Lauren Tilton, Assistant Professor of Digital Humanities in the Department of Rhetoric & Communication Studies and Research Fellow in the Digital Scholarship Lab (DSL), University of RichmondDr. Scott Saul, Professor of English, University of California, BerkeleyDr. Michael J. Kramer, Assistant Professor, Department of History, State University of New York-Brockport