Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 20

October 25, 2022

A Well-Guarded Safe-Deposit Box

The history locked in the object can only be delivered by a knowledge mindful of the historic positional value of the object in its relation to other objects—by the actualization and concentration of something which is already known and is transformed by that knowledge. Cognition of the object in its constellation is cognition of the process stored in the object. As a constellation, theoretical thought circles the concept it would like to unseal, hoping that it may fly open like the lock of a well-guarded safe-deposit box: in response, not to a single key or a single number, but to a combination of numbers.

— Theodor Adorno, Negative Dialectics

October 22, 2022

On Your Marx

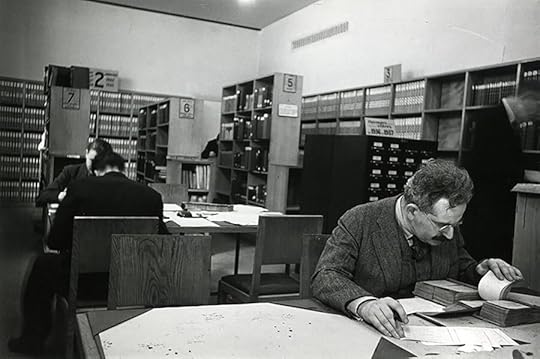

There is a specter haunting our contemporary culture, the specter of Marxism. Is it still relevant a decade after its revival in response to the 2008 housing crisis and economic recession in the United States? How does Marx play these days?

Howard Zinn is most famous for his bestselling book A People’s History of the United States, but he also wrote plays, including a curious one recently revived by Jack Simel at the MuCCC in Rochester, New York that features a back-from-the-dead Marx mistakenly delivered from heaven to Soho in New York City instead of Soho, London. Marx is back, newspaper clippings and beer in hard, in order to take stock of the modern world. Written in 1999, Zinn’s play is, at times, a bit ponderous and plodding, but it also has its clever moments. It requires, as any one-person play does, enormous focus on the part of the performer, and at times Simel struggled to maintain flow and energy—but then again, so has Marxism itself.

By mixing together Marx’s reminiscences about his personal life with explanations of his theories, Zinn’s play manages to bring across the enormous power of Marxism as an explanation of capitalism’s ills. It also tries to imagine how Marx himself would have imagined communism itself at the end of the twentieth century. Would he reckon with the monstrous sins committed in its name—not to mention its dissolution, by and large, by century’s end? Yes, Zinn seems to think, Marx would do so. Nonetheless, he would also cling to his analysis of capitalism, and retain hope for the possibilities of socialist revolution, with its capacity, potentially, to fundamentally link individual freedom to the full collective emancipation of all humans and their world.

How to dramatize these rather heady, philosophical, academic matters? Zinn’s solution is to portray a comical, breaking-the-fourth-wall awareness of the preposterous idea that Marx himself could return to earth. There are Brechtian aspirations here, and repeated references to fellow residents of heaven from Gandhi to Jesus. Whenever Marx trods too close to a loaded topic, the lights in the theater flash on and off, a censorious message from his celestial keepers. Zinn also spends much time on Marx’s personal life, particularly his memories of intellectual fisticuffs with rivals such as the anarchists Proudhon and Bakunin as well as his sad air of failure concerning the disconnections he experienced between himself and his wife Jenny.

Overall, the play reminds us that even as Marx ages, his core question remains relevant: why does capitalism fail to deliver fully on its promise; why did communist revolutions of the twentieth-century go so Stalinistically wrong; how does the dream of connecting individual freedom to collective emancipation live on even as Marx heads back to heaven? What are the afterlives of Marx himself and the theories he so potently proposed?

Seeing Marx in Soho reminded me of Raoul Peck’s very different approach in the 2017 film The Young Karl Marx. Peck chose to shift from the afterlife of Marxism to the prelife of it, offering up nothing less than a bromance film between Marx and his loyal partner Friedrich Engels. At times, the film is as cheesy as it is surprising, but the bromantic fun works: we are pulled in not to postpartum analysis but rather the rush of history. The surprising closing montage of the film really quickens the pace, telescoping from Marx’s youth to contemporary times in an exhilarating sequence that rumbles like a rolling stone across time, presenting in accelerating speed all of the obscene traumas and the continued hopes for humanity after Marx’s youth, which are as much a part of the Marxist story as his own life and thinking.

Stefan Konarske and August Diehl as Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx in Raoul Peck’s The Young Karl Marx.

Stefan Konarske and August Diehl as Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx in Raoul Peck’s The Young Karl Marx.Young Marx or old, bromantic or back from the dead, the man, his life, and his theories continue to provide not just backstory, but also beliefs and ideas we must reckon with to this day. We should continue to think about him, not with romantic naiveté but rather with dramatic attention. The story of his stages of history are not over. Seeming to simmer nostalgically, safely in the past, if not getting outright buried in the cold, hard ground, Marx in fact boils on, raging into the future.

October 11, 2022

In the Neighborhood of Art

Being a critic is like being a medium, when it comes on you you can’t not do it. Usually, though, you can avoid writing it down. When you can’t, you should be careful to point out that criticism is not about art, it is only thinking “in the neighborhood of art.”

— Dave Hickey, “Available Light”

Three-Step Prose

Work on good prose has three steps: a musical stage when it is composed, an architectonic one when it is built, and a textile one when it is woven.

— Walter Benjamin, One Way Street

September 22, 2022

What Is Mountain Music?

Bruce Molsky. Photo: Steve Ford.

Bruce Molsky. Photo: Steve Ford.There is a moment in the chorus of songs such as “Jack of Diamonds” and “Green Grows the Laurel” when Bruce Molsky brings his voice up around the melody to the major third of the tonic just before he returns from the hinge-like dominant chord back to the root note. Most singers would go right in through the front gate of the starting note of the home chord, but not Molsky; instead he cleverly jumps the fence, or maybe better said uses a little melodic step ladder to bring us up and over it before we arrive back to the hearth. It’s a magical, signature move and part of what makes Molsky such a pleasure to listen to as a musician.

To get technical for a moment, since the major third is a sweet note and yet also the sixth note in the dominant chord, the melody hangs in the air more uncertainly for a second before coming back down. Then Molsky slams the door shut, bringing us in safely in from the cold. The melodic choice jumps up, anticipates resolution, pauses for a moment above it, then settles back into it. Molsky traces the steps along the way, hopscotches his voice across the stones in the path, but always gets back back where he was headed all along. The effect of this little melodic flourish is maybe that it helps us notice some stormy clouds gathering on the horizon, maybe some regrets and sadnesses and worries around the edges, but then we still land on our feet, returned to home, to a place of comfort and stability.

Performing in Hatch Recital Hall at Eastman School of Music as part of the Rochester Fringe Festival, Molsky presented “an evening of mountain music”; but what mountain were we on here, exactly? One with a vista, that’s for sure, a way of glimpsing distant shores while knowing where we stand. We heard classic Appalachian fiddle tunes, of course but also Northern Ontario and Finnish ones, guitar blues, Celtic fingerpicking, even a new, contemporary singer-songwriter composition reimagined for the banjo. In between the songs, Molsky told stories, jokes, and welcomed the audience into his world.

Center stage, he actually kept directing our ears and eyes elsewhere: to the community of characters, stories, gestures, feelings, foreign countries, familiar places, and uncanny moments in the songs. There was a pining lover swearing oceanic fidelity to a beloved across the seas; a country boy bopping down the road to see his sugar babe, glad to have everyone watching him do so, and a little adorably goofy and embarrassing for that fact; a lonely old man by a fire, not so much looking back on his life but living in the moment of his older age and its slowing, thickened soup of memories; a devilish showman playing tricks on us with his legerdemain; a woman too smart, kind, and giving for anyone around her; even a fiddle tune (“Bonaparte’s Retreat”) that Aaron Copland stole, which resonated nicely, both symbolically and sonically, in a classical music hall.

Molsky as musician is that rare thing: a sturdy radical. His sound is solid, grounded, earthy, yet it also flies. There are times when you feel like three fiddlers are playing, not one, but the point is not virtuosity, it is relational energy. He circles up around the root note to seek out, in fact, the root of things, as radicals should do. After all, you can only soar effectively if you know how to keep your balance. Likewise, you can only return home if you know how to get a bit off-kilter and wild on the way there. It’s all there: the ups and downs, the outward glance and the inward core, the tripping and regaining of your stride, the stepping out and the looking back, the leap and the return, the pluck and the swerve. The opposites dance, waltzing, double stopping, pushing onward, lifting and bowing, climbing and falling. It’s a puzzling jig and a jigsaw puzzle, assembled together, teetering confidently atop the peak of Molsky’s total, mountainous sound.

September 20, 2022

Elemental Responses to Climate Change

In Elemental Forces Redux, Missy Pfohl Smith and Biodance join with the Dave Rivello Ensemble and digital media artist W. Michelle Harris to present movement, music, and video art inspired by the climate crisis. There is a sense of urgency in the work, but more so an effort to remain balanced in the face of suffering, chaos, anxiety, fear, and disorder. In a historical moment when the opportunity to “solve” climate change has rapidly given way to a focus on adjusting to living with it, Elemental Forces Redux reminds us to remember that not all is lost. There is heightened awareness, community, and beauty to be found still, Biodance proposes, even if the overall crisis cannot be averted; and, as Smith points out at one point during the performance, in a text about how rapidly the earth began to heal during the Covid-19 shutdown, who knows if maybe dramatic improvements can still occur?

The dance begins with a long list of locations on the video screen, all affected by climate change through floods, fires, or other intensified weather events. There are so many places listed one might conclude, rightly, that climate change is affecting everyone everywhere. This interplay of scale between the specific and the universal, this specific place and every place, persists throughout the work. The four sections of Elemental Forces, after all, names all four: Water, Earth, Fire, and Air, with Wind added for good measure. Nothing is left out, but within the totality of the elements, very particular stories and details emerge in short, informational texts read from clipboards by individual dancers. The movement also integrates the distinctive with the general—the dancers often gradually shift from basic human gestures of walking, holding, standing, sitting, swaying, leaning, and turning to stranger, more startling movements: leaping, twisting, jabbing, falling, crawling, popping, contorting. These progressions from the familiar to the more unconventional convey a nagging, lurking sense of the world gone awry with climate change—still our world, but yet increasingly a transformed and troubling setting.

The first section, Wind, featured a slowly developing work inspired by a site-specific performance in Powder Mills Park, featured dancers swaying like trees, then moving into a nicely composed circle. The movement takes awhile to develop, but then it catalyzes into an energetic buzz of centripetal energy, dancers composed into whirling circles at the center of the stage, a gravitational pull. Limbs may bend, but roots center.

Water, the next section, started with a solo by bass clarinet, that most human tonality of reed instruments, and a kind of Gregorian chant choral singing by the band. This accompanied a marvelous duet between two of the dancers, marked by explorations of pause and flow. The dancers slowly spun in parallel and then flipped around and over each other with a deceptively easy grace. An especially evocative moment was when one of the dancers held the other on the hip in a slow spin, so that both seemed weightless for a moment. Then they came back to earth, leaning and twisting around each other, always in control but always at the edge of imbalance, like currents coming up against the banks of the river, bouncing back, hinting at the undertow. This watery movement suggested the beauty of water but always with a hint that something might at any moment overflow and overwhelm. This element so essential to tranquility, peace, nourishment, survival, can also, with more force, more pressure, destroy everything in its path.

A wonderful trumpet solo by Mike Kuapa splatted the air with sweet and sour notes in the Earth section. Indeed, the music by the Rivello Ensemble had an Ellingtonian savviness to it, filled with thick harmonies, tasteful solos, and an interest in a wide range of timbres and sounds. The ensemble could move from the ethereal to the elemental with dexterity. As the dancers segued from movements familiar to ones more uncanny, so too the music could go from something like a conventional keyboard solo with typical jazz harmonies to a vibratory drone of a bass note that hummed along on the line between noise and music. In Fire, for instance, the brass and reeds jumped like popcorn but the rhythm section maintained an insistent groove. The contrast worked well with Smith’s solo, a kind of slowing intensifying ripple and crackle of energy that played with the dynamic of steady heat and bursts of flame. At times, the music pushing momentum onward, Smith seemed almost to dissolve into the infrared video by Harris projected behind her: a small part of the larger inferno which was, of course, only constituted by its many individual conflagrations. After Fire, most of the Biodance ensemble returned for Air, once again starting from calm, circular motions that were, here and there, by the end of the section, broken up into sudden, more strident upright stepping almost reminiscent of Irish dance.

There was, overall, a kind of reserved calm to Elemental Forces Redux even as it confronted the traumas of climate change and the power of elements that humans have so disturbed. We might pay attention, the performance suggested, to how the human motor fits into this larger, troubling atmosphere of nature out of whack. We might sound out how the human sensorium relates to the larger biosphere. To feel, hear, and see the elements by at once embodying them yet also noticing their otherness is to attempt to reconfigure how humans relate to the natural world. We are, after all, at once in it, of it, and yet alienated from it. To return to elemental forces as Biodance does is to not ask if we can solve the problems of Mother Nature, but rather if we can resequence the patterns of human nature. Can we rethink its wildness and abandon, its urge for control and subordination, its penchant for needing to master things, its drive for freedom, and its possibilities for solidarity and community? We must reimagine ourselves to confront climate change, but what’s funny, and always lurking in Elemental Forces Redux, is that the elements ultimately don’t care if we do or not.