Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 17

March 1, 2023

Instrumental

Constance and Charles Seeger with young son Pete, 1921.

Constance and Charles Seeger with young son Pete, 1921.A musical instrument is an artifact; the musician dances upon it—even with it, as may a dancer, too.

— Charles Seeger, “Toward a Unitary Field Theory”

February 28, 2023

Rovings

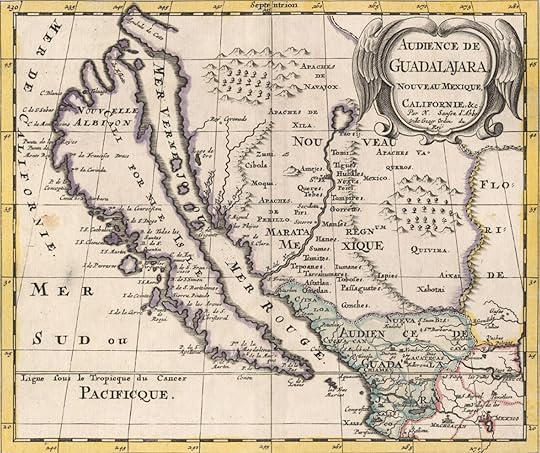

Nicolas Sanson, Audience de Guadalajara Nouveau Mexique Californie, Etc., 1657.SoundsTweedy, “Opaline”Various Artists, All Bad Boy & All Good Girl: Manchester Street Soul Soundtapes, 1988-1996 Utah Philips, Loafer’s Glory: A Hobo Jungle of the MindJake Blount, The New FaithThe Chatterlys, BBC Sounds Drama 3Open Country: Folk on the Hills, BBC SoundsVarious Authors, The Essay: Walking the Causeways, BBC SoundsMarvel’s WastelandersWays of ListeningPeter Seeger, “Foolish Frog”Billie Eilish, “TV”Our Native Daughters, “Quasheba, Quasheba”Tommy McLain featuring Elvis Costello, “I Ran Down Every Dream”Katie Pruitt, “Something About What Happens When We Talk” (Lucinda Williams cover)Béco’s Brazil: New Sounds for 2023, New SoundsDavid Byrne Radio Presents: Music for Valentines WordsSteve Elman, “Classical Album Review: Wadada Leo Smith: String Quartets Nos. 1 – 12, played by the RedKoral Quartet and Guests,” The Arts Fuse, 26 January 2023Various Authors, “The 1619 Project Forum,” American Historical Review 127, 4, December 2022, 1792–1873John Summers, “The Examined Life: Anti-Memoirs of Autism,” The Point, 30 November 2022 Seth Garfield, “A Taste of Brazil: How Guaraná Soda Became a National Icon,” Not Even Past, 3 January 2023Richard Polenberg, Hear My Sad Story: The True Tales That Inspired “Stagolee,” “John Henry,” and Other Traditional American Folk SongsNia T. Evans, “Revolution Is a Great Work of Art,” Hammer and Hope 1, Winter 2023Derecka Purnell, Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylo, “After the Uprising, What Is to Be Done? A discussion of the legacy of the 2020 protests, the growing threat from the right, and building movements,” Hammer and Hope 1, Winter 2023Becca Rothfeld, “What Chatbots Can’t Do,” Forms of Life, The Point 24 February 2023Stephen Winick, “Ten Thousand Cattle for Our One Thousandth Post,” Folklife Today, 22 February 2023Thomas Rodgers, “An Artist’s Queer Take on ‘Moby-Dick’,” New York Times, 20 February 2023“Walls”Glenstone MuseumVisualizing Place: Maps from The Bancroft Library @ Bancroft Library, University of California BerkeleyDenyse Thomasos: just beyond @ Art Gallery of Ontario

Nicolas Sanson, Audience de Guadalajara Nouveau Mexique Californie, Etc., 1657.SoundsTweedy, “Opaline”Various Artists, All Bad Boy & All Good Girl: Manchester Street Soul Soundtapes, 1988-1996 Utah Philips, Loafer’s Glory: A Hobo Jungle of the MindJake Blount, The New FaithThe Chatterlys, BBC Sounds Drama 3Open Country: Folk on the Hills, BBC SoundsVarious Authors, The Essay: Walking the Causeways, BBC SoundsMarvel’s WastelandersWays of ListeningPeter Seeger, “Foolish Frog”Billie Eilish, “TV”Our Native Daughters, “Quasheba, Quasheba”Tommy McLain featuring Elvis Costello, “I Ran Down Every Dream”Katie Pruitt, “Something About What Happens When We Talk” (Lucinda Williams cover)Béco’s Brazil: New Sounds for 2023, New SoundsDavid Byrne Radio Presents: Music for Valentines WordsSteve Elman, “Classical Album Review: Wadada Leo Smith: String Quartets Nos. 1 – 12, played by the RedKoral Quartet and Guests,” The Arts Fuse, 26 January 2023Various Authors, “The 1619 Project Forum,” American Historical Review 127, 4, December 2022, 1792–1873John Summers, “The Examined Life: Anti-Memoirs of Autism,” The Point, 30 November 2022 Seth Garfield, “A Taste of Brazil: How Guaraná Soda Became a National Icon,” Not Even Past, 3 January 2023Richard Polenberg, Hear My Sad Story: The True Tales That Inspired “Stagolee,” “John Henry,” and Other Traditional American Folk SongsNia T. Evans, “Revolution Is a Great Work of Art,” Hammer and Hope 1, Winter 2023Derecka Purnell, Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylo, “After the Uprising, What Is to Be Done? A discussion of the legacy of the 2020 protests, the growing threat from the right, and building movements,” Hammer and Hope 1, Winter 2023Becca Rothfeld, “What Chatbots Can’t Do,” Forms of Life, The Point 24 February 2023Stephen Winick, “Ten Thousand Cattle for Our One Thousandth Post,” Folklife Today, 22 February 2023Thomas Rodgers, “An Artist’s Queer Take on ‘Moby-Dick’,” New York Times, 20 February 2023“Walls”Glenstone MuseumVisualizing Place: Maps from The Bancroft Library @ Bancroft Library, University of California BerkeleyDenyse Thomasos: just beyond @ Art Gallery of Ontario“Stages”Endgame @ Washington Guild Theater, 16 February 2023David Blight, Frederick Douglass Prophet of Freedom @ Library of America, 16 February 2023Keith David, Speech delivered by Frederick Douglass at the National Convention of Colored Men in Louisville, Kentucky on 24 September 1883 @ The Frederick Douglass Project, Theater of War Productions/Penn State University, 9 February 2023Jon Langford @ Judson & Moore Distillery, 19 February 2023Peter Guralnick, Adventures in Music and Writing @ NYPL, 3 February 2023Graham Nash @ Library of Congress, 31 January 2014Tim Barringer, Why We Need Ruskin Now @ Getty Museum, 15 June 2022The Multiple Reinventions of the Américas in Context @ Getty Reserch Institute, Parts 1 and 2 Kevin Butterfield and Sophia Rosenfeld, Democracy and “Common Sense”@ Library of Congress, 3 February 2023By Alison Knowles: A Symposium @ Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, 4 November 2022Bruce Barthol @ The MimeCast, 27 July 2020ScreensMichael Snow, New York Eye and Ear ControlWild Tales (Relatos Salvajes)

February 27, 2023

The Phantom Public

Photo: Michael J. Kramer, Alexandria, VA.

Photo: Michael J. Kramer, Alexandria, VA.

February 24, 2023

Dustbowl Empiricism

I worked from history to theory, and I tried to use theory to inform but not imprison my understanding of historical experience. An anti-theoretical bias is particularly strong in Anglo-American historical circles: in part it represents a healthy suspicion of fashionable (usually French) slogans and catchwords masquerading as ideas. But the hostility to theory can also be rooted in a narrow and unimaginative cast of mind: Alfred North Whitehead called it ‘dustbowl empiricism.’ …My own view is that without an occasional dose of speculative boldness, historians are doomed to the deadly antiquarianism for which they have rightly been scorned, since George Eliot gave us the archetypal pedant-historian Casaubon in Middlemarch.

— Jackson Lears, Preface (1983) to No Place of Grace: The Quest for Alternatives to Modern American Culture, 1880-1920

She Fell In Love

Eric Singer of Kiss, with a double kick drum.

Eric Singer of Kiss, with a double kick drum.Wilco’s masterpiece pop song “Heavy Metal Drummer,” from the celebrated 2001 album Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, is about many things: youth, aging, sincerity, taste, immediacy, distance, summertime, bleached blond hair, double kick bass drum pedals, the pleasures of listening, sweet smell of pot smoke, the pleasures of watching someone else listening, the pleasures of the cover song, the meaning of bliss.

It is a song about heavy metal that is not a heavy metal song. A nostalgic reverie that streaks past the past into a glorious dad-rock future. A sincere missive to an ironic appreciation. A shiny shiny pants fable about dudes in Kabuki makeup and outrageous platforms. A jealous gaze upon even oneself one day thrashing out devil’s triads on stage in front of the adoring crowd. A love letter to a fan, maybe to fandom itself.

It starts with a tinny, off-kilter drum machine fill that gives way to a propulsive trap-drum beat worthy of a 1979 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am. Ringing mixolydian chords circle around and around, flowing out over the landing in the summer, by the water, absorbed into the reefer wafting out over the Twainian Chuck Berry riffage of foggy Mississippi River riverbanks. It ends with a looping mystic crystal revelation of bubbling postlapsarian glitter glow, the chords leaving behind a gurgling spin of fairy dust that spirals out over the caked makeup faces, abandoned cracked plastic beer cups, and cigarette butts at the concert ending.

In between, classical music masks Kiss tunes, but they can’t quite drown out the sound. Maybe one can indeed rock and roll all nite into eternal youth. There is a mish-mashing of taste levels into a new holistic aesthetic of the American beautiful. Midwestern sublime. Grimy, Detroit Rock City St. Louis metro-area grind meets oracular individual epiphany combined with collective euphoria. I would not feel so all alone, everybody must get stoned. There is imitation and originality. Cover songs leading to original insights. Roll over Beethoven. At the landing, it’s summertime and the living is easy. Somewhere in there: crickets.

What “Heavy Metal Drummer” might be most about, however—the secret that unlocks the song—is love: love forming, love in motion, love’s foolishness, love’s serious power, love is king. In this case the object of love is the heavy metal drummer. Maybe the object of affection is also an older man’s glance back to a moment of youthful happiness suspended in time. Yet these objects of love are but sticks twirling in the air. They are not the actual subject of the song. The actual subject is the feeling of falling in love itself. Falling in love with music, with a location, with a memory, with the hum of human time, with the things that make us tick. She fell in love with the drummer. Another and another. She fell in love.

What matters is not that the woman whom the song’s narrator is watching intently fell in love with the heavy metal drummer. The drummer is ridiculous in his shiny shiny pants and bleached blond hair, mugging for the crowd. What matters most is not even the way in which the young woman, like so many adolescent female fans (who are in fact the protagonists, the rock stars of rock music), then fell in love with the next drummers in the next heavy metal bands to come through town to perform at the landing in the summer. It’s the next line of the song that counts: she fell in love. She fell in love with falling in love. And so has the singer himself. And so maybe have we, the listeners.

It is the heavy metal’s drummer’s fate to be but the vehicle, revving away with two feet on the double kick drums, for this desire. Maybe this is the musician’s fate more generally. Music is the alchemical catalyzer of the perception of falling in love. We miss the innocence we have known, but the knowledge is better. So says the backup vocalist (bassist John Stirratt) in “Heavy Metal Drummer,” who affirmatively gasps in falsetto joy at the insight.

The song pommels onward, chords churning, rotating, turning, form the root to the dominant, the major to the minor to the major again. We are refreshed in the memory of falling in love, touching that feeling again, feeling it in ourselves, seeing it in others, bringing it into the present. We recover it by missing it. Then it fades out, kissing off.

February 23, 2023

February 11, 2023

January 31, 2023

Rovings

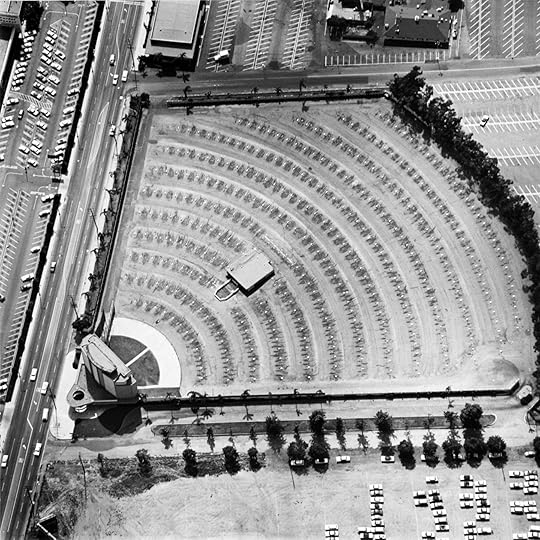

Ed Ruscha, Gilmore Drive-In Theatre, 6201 W 3rd St. from the series Parking Lots, 1967/1999.SoundsPacific Gas & Electric, “Staggolee”Tim Daisy, New Works For Solo PercussionTim Daisy & Ikue Mori, Light and ShadeThe Compass—Sounds of the City: Los Angeles, BBC SoundsMargarida Garcia, Good NightLuther Davis & Hus Caudill, Old-Time Galax-Style Twin Fiddling recorded by Tom Carter & Blanton OwenKate Fagan, “I Don’t Wanna Be Too Cool”Various Artists, The Sun is Setting on the WorldYasmin Williams, Urban Driftwood Pigeon Pit, feather river canyon bluesLisel, Patterns For Auto-Tuned Voices And DelayTheophilus Oluwafifehami Ajayi, “Destination To West Africa”Biensüre, “Cawa”Michael Snow, “Conference: Subject: 3 Inches = 77 Milimetres = 3 Min 30 Sec,” Hearing AidFelipe Perez y Sus Polkeros, “Las Criadas,” Dulce SueñosSir Lancelot, “Atomic Energy”Pete Seeger, “Talking Atom”Sam Hinton, “Old Man Atom”David Grubbs, On Derek Bailey, Roulette Intermedium PodcastHastagPublicEnemy, BBC Sounds DramaTom Verlaine, Gaylord Fields Show, WFMU 6 January 2006Jacueline Nova, Creation of the Earth: Throbbing Echoes of Jacqueline Nova—Electroacoustic and Instrumental Music (1964-1974)WordsGayl Jones, PalmaresMick Herron, London RulesAmanda Petrusich, “David Crosby Understood the Sharpness of Despair,” New Yorker, 24 January 2023Allyson McCabe, “She Brought New Sounds to Colombia. The World’s Catching Up,” New York Times, 20 January 2023Jeremy Gordon, “Wax Cylinders Hold Audio From a Century Ago. The Library Is Listening,” New York Times, 02 January 2023Gagosian Quarterly, Winter 2022 Wilfred Chan, “‘It’s a strange moment we live in’: MLK sculptor on backlash to monument,” Guardian, 19 January 2023Charles Capper, “‘A Little Beyond’: The Problem of the Transcendentalist Movement in American History.” Journal of American History 85, 2 (1998): 502–39Jennifer Wilson, “John le Carré’s Search for a Vocation,” New Yorker, 16 January 2023Merve Emre, “Has Academia Ruined Literary Criticism?,” New Yorker, 23 January 2023Rhea Nayyar, “An Afternoon in the Park With Shahzia Sikander’s Golden Monuments,” Hyperallergic, 24 January 2023Alyssa Battistoni, “Latour’s Metamorphosis,” Sidecar—New Left Review, 20 January 2023Chris Wright, “The Radicalism of Working-Class Americans by Chris Wright,” Labor Online, 11 January 2023Dylan Riley & Robert Brenner, “Seven Theses on American Politics,” New Left Review 138, November/December 2022Tim Barker, “Seven Theses on Brenner and Riley’s ‘Political Capitalism’,” Origins of Our Time Substack, 24 December 2022Margaret O’Mara, “Are You Better Off than You Were Four Years Ago? The Economy in Presidential Politics,” Perspectives on History, 10 September 2020“Walls”Vittore Carpaccio: Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice @ National Gallery of Art Vermeer’s Secrets @ National Gallery of ArtRomare Bearden: Artist, Activist, and Advocate of the Promised Land @ BYU Museum of ArtIn the Shadow of Mt. Tam @ Anthony Meier GalleryEd Ruscha, Parking Lots @ Yancey Richardson Gallery Brad Stumpf, Shadow Plays @ HarkawikRick Lowe, Notes on the Great Migration @ Neubauer Collegium “Stages”The Tempest @ Roundabout Theatre, 28 January 2023Partch Ensemble Making Music: Daniel Rothman, 8 December 2022Partch Ensemble Making Music: TJ Troy, 6 December 2022John Zorn and Bill Laswell, Turbines @ Gagosian, 19 December 2023Meridian Brothers @ New Sounds, WNYC, 23 January 2023Yo La Tengo with Sun Ra Arkestra horns @ Bowery Ballroom, 25 December 2022Ron C. Judd, Red Scare Politics at Western Washington University @ Whatcom Museum, 8 February 2018Elijah Wald, “A Tribute to Samuel Charters” @ ARSC Conference, 28 May 2015The Theodore Roszak Papers in Focus @ Stanford Library Special Collections, 15 November 2022ScreensAmie Siegel, The Architects, Hyundai Card Video Views, MoMA MagazineHy Hirsh, Come CloserArgentina, 1985Jack Ryan, Season 03CasinoHunters, Season 02

Ed Ruscha, Gilmore Drive-In Theatre, 6201 W 3rd St. from the series Parking Lots, 1967/1999.SoundsPacific Gas & Electric, “Staggolee”Tim Daisy, New Works For Solo PercussionTim Daisy & Ikue Mori, Light and ShadeThe Compass—Sounds of the City: Los Angeles, BBC SoundsMargarida Garcia, Good NightLuther Davis & Hus Caudill, Old-Time Galax-Style Twin Fiddling recorded by Tom Carter & Blanton OwenKate Fagan, “I Don’t Wanna Be Too Cool”Various Artists, The Sun is Setting on the WorldYasmin Williams, Urban Driftwood Pigeon Pit, feather river canyon bluesLisel, Patterns For Auto-Tuned Voices And DelayTheophilus Oluwafifehami Ajayi, “Destination To West Africa”Biensüre, “Cawa”Michael Snow, “Conference: Subject: 3 Inches = 77 Milimetres = 3 Min 30 Sec,” Hearing AidFelipe Perez y Sus Polkeros, “Las Criadas,” Dulce SueñosSir Lancelot, “Atomic Energy”Pete Seeger, “Talking Atom”Sam Hinton, “Old Man Atom”David Grubbs, On Derek Bailey, Roulette Intermedium PodcastHastagPublicEnemy, BBC Sounds DramaTom Verlaine, Gaylord Fields Show, WFMU 6 January 2006Jacueline Nova, Creation of the Earth: Throbbing Echoes of Jacqueline Nova—Electroacoustic and Instrumental Music (1964-1974)WordsGayl Jones, PalmaresMick Herron, London RulesAmanda Petrusich, “David Crosby Understood the Sharpness of Despair,” New Yorker, 24 January 2023Allyson McCabe, “She Brought New Sounds to Colombia. The World’s Catching Up,” New York Times, 20 January 2023Jeremy Gordon, “Wax Cylinders Hold Audio From a Century Ago. The Library Is Listening,” New York Times, 02 January 2023Gagosian Quarterly, Winter 2022 Wilfred Chan, “‘It’s a strange moment we live in’: MLK sculptor on backlash to monument,” Guardian, 19 January 2023Charles Capper, “‘A Little Beyond’: The Problem of the Transcendentalist Movement in American History.” Journal of American History 85, 2 (1998): 502–39Jennifer Wilson, “John le Carré’s Search for a Vocation,” New Yorker, 16 January 2023Merve Emre, “Has Academia Ruined Literary Criticism?,” New Yorker, 23 January 2023Rhea Nayyar, “An Afternoon in the Park With Shahzia Sikander’s Golden Monuments,” Hyperallergic, 24 January 2023Alyssa Battistoni, “Latour’s Metamorphosis,” Sidecar—New Left Review, 20 January 2023Chris Wright, “The Radicalism of Working-Class Americans by Chris Wright,” Labor Online, 11 January 2023Dylan Riley & Robert Brenner, “Seven Theses on American Politics,” New Left Review 138, November/December 2022Tim Barker, “Seven Theses on Brenner and Riley’s ‘Political Capitalism’,” Origins of Our Time Substack, 24 December 2022Margaret O’Mara, “Are You Better Off than You Were Four Years Ago? The Economy in Presidential Politics,” Perspectives on History, 10 September 2020“Walls”Vittore Carpaccio: Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice @ National Gallery of Art Vermeer’s Secrets @ National Gallery of ArtRomare Bearden: Artist, Activist, and Advocate of the Promised Land @ BYU Museum of ArtIn the Shadow of Mt. Tam @ Anthony Meier GalleryEd Ruscha, Parking Lots @ Yancey Richardson Gallery Brad Stumpf, Shadow Plays @ HarkawikRick Lowe, Notes on the Great Migration @ Neubauer Collegium “Stages”The Tempest @ Roundabout Theatre, 28 January 2023Partch Ensemble Making Music: Daniel Rothman, 8 December 2022Partch Ensemble Making Music: TJ Troy, 6 December 2022John Zorn and Bill Laswell, Turbines @ Gagosian, 19 December 2023Meridian Brothers @ New Sounds, WNYC, 23 January 2023Yo La Tengo with Sun Ra Arkestra horns @ Bowery Ballroom, 25 December 2022Ron C. Judd, Red Scare Politics at Western Washington University @ Whatcom Museum, 8 February 2018Elijah Wald, “A Tribute to Samuel Charters” @ ARSC Conference, 28 May 2015The Theodore Roszak Papers in Focus @ Stanford Library Special Collections, 15 November 2022ScreensAmie Siegel, The Architects, Hyundai Card Video Views, MoMA MagazineHy Hirsh, Come CloserArgentina, 1985Jack Ryan, Season 03CasinoHunters, Season 02

January 30, 2023

Liberty Tree

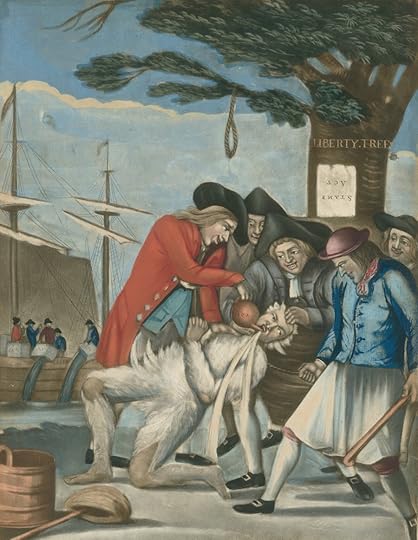

Philip Dawe (attributed), The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering Commissioner of Customs John Malcolm, 1774.

Philip Dawe (attributed), The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering Commissioner of Customs John Malcolm, 1774.Typically, pundits portray contemporary American politics in both-siderism parallel, with an extreme right, an extreme left, and a middle caught in…well, the middle.

Perhaps this isn’t quite accurate. From the outside, looking at who is currently able to exercise power, the comparison does not line up. Moderate Democrats exercise power, to be sure, as do extreme-right Republicans. By contrast, those who seem to lack effective power in the contemporary dynamic are those on the left of the Democratic Party and those few moderates remaining in the Republican Party. It is the left-wing of both parties (if one really can can call the few remaining moderate Republicans such a thing) that lacks concrete power. They are the elected officials who struggle to enact policy.

The real battle for power today is between the right-wing of both parties. The question being legislated is something like: Should the US to be a center-left, corporate-dominated, democracy with some incomplete but not completely absent social democratic tendencies, or is it to be a fascist fantasy of guns, patriarchy, white supremacy, and anything-goes libertarianism? This seems to be the fight. It’s not a bipartisan-center versus extremist wings configuration, but rather a which more conservative vision will triumph.

This is not to say that more left-wing politics (national healthcare, so-called soft infrastructure, environmental transformation, even wealth redistribution) are unimportant. Not at all. The views, policy positions, and public personae of Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, etc. matter. So too, of course, does the presence of Never-Trumpers and other conservative, but not crazy-conservative, Republicans. These figures matter. But, do they really control anything in a foundational sort of way? In the end, it does not seem so.

In this sense, it does no good to line up the parties as if they were parallel. Extreme right-wing Republicans exert far more real political force than those on the so-called extreme left of the Democratic Party. The comparison is false. The actual power held is deeply unequal, never mind the differences in sanity of the policy proposals or the willingness to work within existing norms.

Meanwhile, more conventional Republicans, the few who remain, are, we might say, far more like the left of the Democratic Party than the center. In terms of their ability to wield power, moderate Republicans lack it. At least this is what it looks like from the outside They are there, but don’t have their hands on the wheels of government even when their party controls a part of it.

In this way, the battle for the future of the United States politically is between the right wing of each party. To grasp this fact is to shift from formulaic portrayals of the American political system as a body with symmetrical wings, which is in fact inaccurate, to a kind of misshapen, windswept tree. Its trunk is tilted toward a corporate-left-liberal center. There are some fragile buds on its left. And even more fragile ones on the center-right. Many of its branches have been torn off in a storm of far-right rage. Perhaps it is the liberty tree.

Shapes. Photo: Michael J. Kramer.

Shapes. Photo: Michael J. Kramer.