Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 15

June 19, 2023

Petty Pace

June 6, 2023

2023 June 06—The Global Jukebox & the Celestial Monochord

A presentation from the book-in-progress, This Machine Kills Fascists: Technology and Folk Music in the USA. Documentarian, ethnomusicologist, and activist Alan Lomax and anthologist, artist, and eccentric bohemian Harry Smith offer us two examples of the collision of folk music with technology in the Cold War era. As the digital computer moved to the center of American culture after World War II, Lomax and Smith worked to connect musical heritage to the “computational imagination.” They absorbed ideas associated with the rise, in the 1950s and 60s, of cybernetics, informatics, systems theory, statistical approaches, and computational thinking. Lomax applied these theories to folk music, using computers to develop what he called a “Cantometrics” system for measuring global performance aesthetics—the way people sang. Smith did not have access to actual digital computers, but he combined his childhood exposure to Theosophy’s neo-Platonic and neo-Pythagorean traditions of measurement with his interests in both information theory and the anthropology of folk music to try to transform, alchemically, the seeming dross of castoff pre-World War II commercial folk music recordings into the potential gold of futuristic post-World War II cultural knowledge. Not without their flaws, Lomax and Smith both wanted to wield computation in service of harnessing the power of intangible heritage as a democratic force in Cold War America and the world.

June 3, 2023

What’s That Sound?

Henry Threadgill. Photo: Rahim Fortune for the New York Times.

Henry Threadgill. Photo: Rahim Fortune for the New York Times.Music is about listening. Nothing I say can mean anything once you start to listen.

— Henry Threadgill

An Angelic Angle

Seeing that painting made me realize that my ninety-degree relationship to the painting was off somehow. In order to really see paintings, I had to see through the painting and see with the painting. I had to get down on the ground on the painting. I had to put my ear to the painting so I could hear it. Do you understand? …And in hearing the painting, what was incidental to that but at the same time totally fundamental, right, was that my angle in relation to the painting was being transformed. I was being drawn down to the zero degree of social conceptualization. What was happening was that I needed to be moved from the position of looking at to the position of looking with. And seeing through. Not seeing through because the painting is transparent or nonexistent, but rather seeing through the painting, seeing by way of the painting, seeing what was on the other side of the painting by way of the painting, seeing the social aesthetic force and practices and life that were on the other side of the painting, and of which the painting is an emanation. …Our angle becomes angelic in this regard. And in so far as our angle becomes angelic, we move from a practice of critical scrutiny to something on the order of devotion.

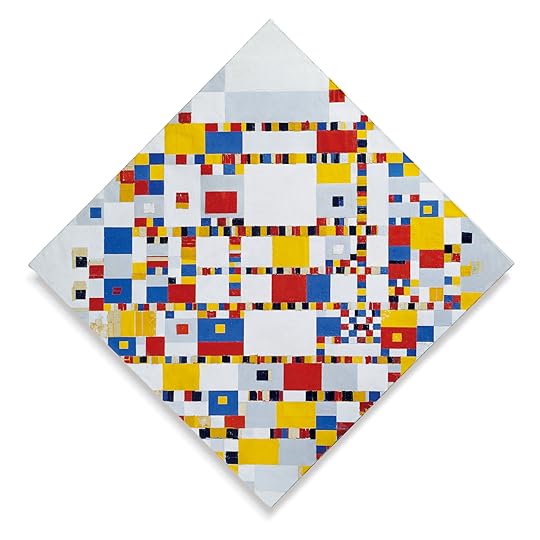

— Fred Moten on looking at Piet Mondrian’s Victory Boogie Woogie

June 2, 2023

We’ve Got Chemistry

By the history of ideas I mean something at once more specific and less restricted than the history of philosophy. It is differentiated primarily by the character of the units with which it concerns itself. Though it deals in great part with the same material as the other branches of the history of thought and depends greatly upon their prior labors, it divides that material in a special way, brings the parts of it into new groupings and relations, views it from the standpoint of a distinctive purpose. Its initial procedure may be said—though the parallel has its dangers—to be somewhat analogous to that of analytic chemistry. In dealing with the history of any philosophical doctrines, for example, it cuts into the hard-and-fast individual systems and, for its own purposes, breaks them up into their component elements, into what may be called their unit-ideas. The total body of doctrine of any philosopher or school is almost always a complex and heterogeneous aggregate—and often in ways which the philosopher himself does not suspect. It is not only a compound but an unstable compound, though, age after age, each new philosopher usually forgets this melancholy truth. One of the results of the quest of the unit-ideas in such a compound is, I think, bound to be a livelier sense of the fact that most philosophic systems are original or distinctive rather in their patterns than in their components.

— Arthur O. Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea

May 31, 2023

Rovings

Joni Mitchell, 1998. Photo: Mark Seliger.SoundsAdoniran Barbosa, “Trem Das Onze”Chico Buarque, CalabarVarious Artists, Florida Folklife from the WPA Collections, 1937 to 1942Jaime de Angulo, Indian Tales radio broadcastsThe Socrates of San Francisco, Archive on 4, BBC SoundsEric Clapton and Bob Dylan, “Sign Language”Charles Ives, Ives Plays Ives: The Complete Recordings of Charles Ives at the Piano“Bob Dylan Birthday Show,” Frow Show, WFMU, 23 May 2023Various Artists, Township JubileeVarious Artists Recorded by High Tracey, Music From the Roadside 1: Music of Africa Series 18: South AfricaVarious Artists Recorded by High Tracey, Music From the Roadside 2: Music of Africa Series 19: Zimbabwe and NeighboursPaul Simon, Seven PsalmsLee Weisert, RecessesMarinho Boffa, Marinho Boffa & String QuartetTyshawn Sorey, For George LewisWordsAmanda Petrusich, “The Sad Dads of the National,” New Yorker, 8 May 2023Ross Scarano, “Lost Ones: Experts agree that memories of rare music can persist for many years,” The Believer, 1 May 2023Howard Fishman, “Before Dylan, There Was Connie Converse. Then She Vanished. There’s a resurgence of interest in the pioneering singer-songwriter who disappeared when she was 50.,” New York Times, 6 May 2023Daniel Sheehy, “Chris Strachwitz: A Life as Art,” Folklife Magazine, 11 May 2023Gary Younge, “how Britain buried its history of slavery,” Guardian, 29 March 2023Lilia Fernandez, “Harold Washington Rainbow Coalition,” Perspectives, 19 April 2023 Steve Babson, “Contemporary Pundits Need a Refresher on Populism’s History,” History News Network, 14 April 2023Skipped History with Ben Tumin, “Slowing Our Roll on Silicon Valley: Interview with Malcolm Harris,” History News Network, 12 May 2023Michael Kazin, “One Big Union: The Red Scare and the fall of the IWW,” The Nation, 29 May/5 June 2023 Rhoda Feng, “Ned Blackhawk Wants to Unmake the US Origin Story: Professor Blackhawk’s new volume attempts to put Native peoples’ stories at the center of the history of the United States,” Mother Jones, 24 April 2023Daniel Dylan Wray, “‘The film industry is gone. It sucks’: Jim Jarmusch on swapping directing for drone rock,” Guardian, 22 April 2023Elisa Hough, “Echoes from the Archives: Almeda Riddle and Mance Lipscomb, 1970,” Smithsonian Folklife Festival Blog, 5 April 2023Dr. Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt, “Leader of American Anthropology Launches WNYC Series,” WNYC/NYPR Archives and Preservation, 17 May 2014Sarah Jane Nelson, ” Ballad Collecting Across the Ozarks: An Introduction to Max Hunter,” Smithsonian Folklife Festival Blog, 18 May 2023Nick Tabor, “No Slouch,” Paris Review, 7 April 2015Cathy van Eck, Between Air and Electricity: Microphones and Loudspeakers as Musical InstrumentsRosemary Levy Zumwalt, American Folklore Scholarship: A Dialogue of DissentErika Brady, A Spiral Way: How the Phonograph Changed EthnographySalmon Rushdie, The Satanic VersesHeloisa Murgel Starling and Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, Brazil: A Biography“Walls”Marisa Metz, Works @ Gladstone GalleryMark Bradford, You Don’t Have to Tell Me Twice @ Hauser & WirthBispo do Rosario, All Existing Materials on Earth @ Americas Society“Stages”Gilberto Gil’s Expresso 2222 Turns 50—A Conversation And Concert @ CLACLS CUNY GC, 30 April 2023W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: A Conversation with Whitney Battle-Baptiste and Britt Rusert @ Cooper Hewitt, 9 May 2023Fred Moten, Observance and Observation @ The Carpenter Center, 13 April 2023Richard III @ Shakespeare in the Park, July 2022 (Great Performances)Kristina Gaddy, Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History @ Filson Historical Society KY, 6 March 2023Improv Nights @ Roulette, 19-21 January 2023Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend @ The Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, 20 April 2023Chet van Duzer, Behold the Mapmaker: Cartographic Self Portraits @ Library of Congress, 19 April 2023 Mack Hagood, Canceling Noise @ UMBCtube, 19 April 2023 Natalia Telepneva, Cold War Liberation: The Soviet Union and the Collapse of the Portuguese Empire in Africa, 1961-1975 @ Washington History Seminar, 2 May 2023 Body Watani Dance Project; Leila and Noelle Awadallah, Terranea: Hakawatia of the Sea @ Arab American National Museum, 28 April 2023 Diana Krall, “For the Roses,” 2023 Gershwin Prize for Popular Song Concert Honoring Joni Mitchell @ DAR Constitution Hall, 1 March 2023Joni Mitchell, Painting with Words and Pictures @ Warner’s Lot in Los Angeles, 1998ScreensNight Train to Lisbon

Zora Neale Hurston: Claiming a Space

My Music with Rhiannon Giddens

The Patients of Dr. García

Joni Mitchell, 1998. Photo: Mark Seliger.SoundsAdoniran Barbosa, “Trem Das Onze”Chico Buarque, CalabarVarious Artists, Florida Folklife from the WPA Collections, 1937 to 1942Jaime de Angulo, Indian Tales radio broadcastsThe Socrates of San Francisco, Archive on 4, BBC SoundsEric Clapton and Bob Dylan, “Sign Language”Charles Ives, Ives Plays Ives: The Complete Recordings of Charles Ives at the Piano“Bob Dylan Birthday Show,” Frow Show, WFMU, 23 May 2023Various Artists, Township JubileeVarious Artists Recorded by High Tracey, Music From the Roadside 1: Music of Africa Series 18: South AfricaVarious Artists Recorded by High Tracey, Music From the Roadside 2: Music of Africa Series 19: Zimbabwe and NeighboursPaul Simon, Seven PsalmsLee Weisert, RecessesMarinho Boffa, Marinho Boffa & String QuartetTyshawn Sorey, For George LewisWordsAmanda Petrusich, “The Sad Dads of the National,” New Yorker, 8 May 2023Ross Scarano, “Lost Ones: Experts agree that memories of rare music can persist for many years,” The Believer, 1 May 2023Howard Fishman, “Before Dylan, There Was Connie Converse. Then She Vanished. There’s a resurgence of interest in the pioneering singer-songwriter who disappeared when she was 50.,” New York Times, 6 May 2023Daniel Sheehy, “Chris Strachwitz: A Life as Art,” Folklife Magazine, 11 May 2023Gary Younge, “how Britain buried its history of slavery,” Guardian, 29 March 2023Lilia Fernandez, “Harold Washington Rainbow Coalition,” Perspectives, 19 April 2023 Steve Babson, “Contemporary Pundits Need a Refresher on Populism’s History,” History News Network, 14 April 2023Skipped History with Ben Tumin, “Slowing Our Roll on Silicon Valley: Interview with Malcolm Harris,” History News Network, 12 May 2023Michael Kazin, “One Big Union: The Red Scare and the fall of the IWW,” The Nation, 29 May/5 June 2023 Rhoda Feng, “Ned Blackhawk Wants to Unmake the US Origin Story: Professor Blackhawk’s new volume attempts to put Native peoples’ stories at the center of the history of the United States,” Mother Jones, 24 April 2023Daniel Dylan Wray, “‘The film industry is gone. It sucks’: Jim Jarmusch on swapping directing for drone rock,” Guardian, 22 April 2023Elisa Hough, “Echoes from the Archives: Almeda Riddle and Mance Lipscomb, 1970,” Smithsonian Folklife Festival Blog, 5 April 2023Dr. Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt, “Leader of American Anthropology Launches WNYC Series,” WNYC/NYPR Archives and Preservation, 17 May 2014Sarah Jane Nelson, ” Ballad Collecting Across the Ozarks: An Introduction to Max Hunter,” Smithsonian Folklife Festival Blog, 18 May 2023Nick Tabor, “No Slouch,” Paris Review, 7 April 2015Cathy van Eck, Between Air and Electricity: Microphones and Loudspeakers as Musical InstrumentsRosemary Levy Zumwalt, American Folklore Scholarship: A Dialogue of DissentErika Brady, A Spiral Way: How the Phonograph Changed EthnographySalmon Rushdie, The Satanic VersesHeloisa Murgel Starling and Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, Brazil: A Biography“Walls”Marisa Metz, Works @ Gladstone GalleryMark Bradford, You Don’t Have to Tell Me Twice @ Hauser & WirthBispo do Rosario, All Existing Materials on Earth @ Americas Society“Stages”Gilberto Gil’s Expresso 2222 Turns 50—A Conversation And Concert @ CLACLS CUNY GC, 30 April 2023W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: A Conversation with Whitney Battle-Baptiste and Britt Rusert @ Cooper Hewitt, 9 May 2023Fred Moten, Observance and Observation @ The Carpenter Center, 13 April 2023Richard III @ Shakespeare in the Park, July 2022 (Great Performances)Kristina Gaddy, Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History @ Filson Historical Society KY, 6 March 2023Improv Nights @ Roulette, 19-21 January 2023Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend @ The Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, 20 April 2023Chet van Duzer, Behold the Mapmaker: Cartographic Self Portraits @ Library of Congress, 19 April 2023 Mack Hagood, Canceling Noise @ UMBCtube, 19 April 2023 Natalia Telepneva, Cold War Liberation: The Soviet Union and the Collapse of the Portuguese Empire in Africa, 1961-1975 @ Washington History Seminar, 2 May 2023 Body Watani Dance Project; Leila and Noelle Awadallah, Terranea: Hakawatia of the Sea @ Arab American National Museum, 28 April 2023 Diana Krall, “For the Roses,” 2023 Gershwin Prize for Popular Song Concert Honoring Joni Mitchell @ DAR Constitution Hall, 1 March 2023Joni Mitchell, Painting with Words and Pictures @ Warner’s Lot in Los Angeles, 1998ScreensNight Train to Lisbon

Zora Neale Hurston: Claiming a Space

My Music with Rhiannon Giddens

The Patients of Dr. García

May 29, 2023

Public History’s Downfall

Pierre Mignard, The Muse Clio, ca. 1689.

Pierre Mignard, The Muse Clio, ca. 1689.History and other humanities fields seem on the ropes these days, put on their heels by a one-two combo: neoliberalism’s sucker punch of adjunctification and the potential body blows of reactionary attacks.

For the last few decades, the response has been a call to go simple and go popular—to “go public,” rather like a private firm selling shares in an IPO in order to raise additional capital. We are told to reject academic specialization for the ability to “speak to the public.”

Lately I have been wondering if this has been a mistake.

To be clear, I write this as a committed public historian curious to see universities and colleges enter into democratic partnerships with other institutions, communities, and individuals. What I have to say here has nothing to do with abandoning this commitment, but rather in seeking to deepen it.

There is a profound irony to the response to the crisis in academic employment now well underway in history and other humanities fields. The call to abandon specialization has only made things worse, not better. Meanwhile, the very fields that have embraced specialization—the infamous STEM fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—are flourishing in terms of funding, political attention, and a kind of common sense belief that they require increased investment. History and the humanities forsake specialization for public orientation and only lose ground; STEM fields double down on specialization exactly as their public orientation—and only gain ground.

Perhaps the mistake made by the history and humanities professions has been to exchange the highly specialized, technical nature of their inquiry for a superficial populist ideology. The fantasy of speaking to an elusive “general audience” by academic historians and humanities scholars now often becomes merely a front for personal and professional self-aggrandizement: a marketing campaign pretending to be a democratic gesture. Even the more earnest attempts to engage in public history and public humanities projects, something I myself have done, can easily slip into an odd posture of forsaking expertise, a kind of self-abnegation that winds up only condescending to others rather than entering into actual honest egalitarian relationships which recognize power differentials without merely trying to faux-reverse them in specious ways.

To be sure, the knowledge of academic historians and other humanities scholars intersects profoundly with knowledge held among non-academics. There are many forms of expertise out there. There are numerous modes of awareness and understanding. This is true of history and the humanities just as it is of STEM fields. The point is not to circle wagons. Neither is it to dissolve scholarly guilds. Rather, the point is to develop trust and make connections across institutional, social, economic, and political boundaries in which there are different kinds of knowledge and perspective that sometimes overlap and sometimes do not.

To do that, however, there need to be professions of history and humanities scholarship in the first place to do the linking up! Just as STEM scholars need to have time to specialize so they can attain certain kinds of new knowledge and offer the public new technologies, healing powers, and ways of comprehending the world, so too we need some people to be professional historians and humanities scholars. But these opportunities are increasingly in profound danger of vanishing.

Sure, we can throw in the towel on this fight, but at least maybe we should not, as a profession, purposely punch ourselves in the face. Plenty of other people are glad to do that for—and to—us. We need not issue self-inflicted wounds.

Yet, we exist in an odd moment currently. Some historians and humanities scholars think that we should over backward and continue to thump away at our own existence, at our specialized training and knowledge. Scientists in the academy don’t undertake these contortions. Neither do the technical fields. Engineers don’t. Lawyers don’t do it. Doctors don’t. Certainly business professors don’t. They defend their advanced knowledge and the support it requires as worthy of funding and they do so precisely because they argue that their specialized labor and knowledge is exactly the thing that is publicly essential. Only historians and humanities scholars currently request public support while, bizarrely, undermining the very thing they are asking the public to bankroll.

Why in Aristotle’s name do history and humanities scholars do this? It makes no sense. Yet the only arguments mustered against the idea have seemed out of touch, never focused on providing more robust support for broader academic employment, only on complaining about usurpations of history and other specialized humanities knowledge by non-experts. That approach will not do.

We might pause to remember that there is a reason it takes many years to complete a PhD in history and the humanities—often longer than in STEM fields. Because it is not easy work. History and the humanities at advanced levels involve highly technical, specialized labor. That is why they are worth funding. Universities and colleges sustain this specialized, technical inquiry into the world and what it means to know it.

Moreover, this often seemingly esoteric pursuit of knowledge and understanding in the academy is precisely what supplies the foundation for higher education’s public mission. Airy flights are the solid grounding! If universities and colleges stop funding specialized research in history and the humanities, they are in fact failing their public mission, not realizing it. They grow increasingly into institutions of higher education in name only. What they have become, instead, are just equivalents to today’s corporations, which employ fictional publicness to sustain private fortunes.

To make the comparison of universities and colleges to corporations of course, raises an obvious point: you need to know your history to think of the parallel situation; you have to be able to formulate a critique based on awareness of that history. Specialized scholarship allows one to do so. To boot, these fields of specialized inquiry are the ones that document the long history of association between capitalist firms and institutions of higher learning in the first place. But you’d need historians and humanities scholars to study these facts fully—or even to be aware of it.

Maybe that’s why scholarly history and the humanities are under such intense attack and why they are so intensely contested in terms of providing support and funding for them to exist at all. These fields produce knowledge that those in power perhaps don’t want to know about—and certainly that they don’t want others knowing about. Because to confront complex and difficult histories and humanities topics would mean having to reckon with their implications fully.

Why is it, then, that only historians and humanities scholars face such pressures—both self-imposed and asserted from without—to make their fields “relevant”? Perhaps because the ultimate goal is to render what they have to teach irrelevant.

May 21, 2023

Free in the Free World, Cool in the Cold War

x-posted from Society for US Intellectual History Book Review.

I wish I knew how it would feel to be free.

—lyrics by Dick Dallas, music by Billy Taylor, sung most famously by Nina Simone

Keep cool but care.

—McClintic Sphere, in V. by Thomas Pynchon

The traumas of World War II raised the stakes not only of geopolitics, but also of personal life. How to carry oneself and treat others in the face of apocalyptic global crisis? The aftermath of the war only intensified these matters. This was a time when “people believed in liberty, and thought it really meant something,” Louis Menand writes in The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War.[1] With their competing visions of economics, politics, and social organization, the United States and the Soviet Union made the question of freedom central to the Manichean struggle between the two nations. The wave of anti-colonial struggles in the postwar era intensified the issue of liberty. Was capitalism or communism the path to achieving it? Could postcolonial modernity prove emancipatory or was it merely a new sort of trap? What did the word freedom even mean in practice? How should one pursue it, enact it, and preserve it at individual as well as collective levels?

For Menand, the Cold War produced a hot house of debates about liberty, without any one position or person or scene providing a definitive perspective. That’s cool, Joel Dinerstein might remark. In his study, however, one particular style emerges as preeminent: what the poet Langston Hughes, borrowing the phrase from vernacular African American culture, called the effort to “play it cool.”[2] Or, as Thomas Pynchon’s Ornette Coleman/Thelonious Monk-inspired character McClintic Sphere phrased it in the 1963 novel V., the goal was to “keep cool but care.”[3] In Menand’s study, there is lots of friction. In Dinerstein’s book, by contrast, one answer to the Cold War’s atmosphere of potential nuclear annihilation, continued injustice, racism, sexism, the legacies of imperialism, and other ills was precisely not to rage and argue uncontrollably, but rather not to get too bothered about anything, yet to do so without giving in to total passivity or cynicism.

To try to make sense of the complexities of Cold War culture—the fiery disagreements about freedom, the pursuit of unflappability in the face of disaster—both Menand and Dinerstein have written sprawling books. Not counting endnote materials, Menand’s doorstopper weighs in at 727 pages of prose. By contrast, Dinerstein’s study comes in at a seemingly meager 459 pages. Are the two books worth all those trees and all that ink? Yes. They are impressive accomplishments. Their differences, however, make them even more intriguing as competing investigations of a crucial moment in American intellectual and cultural history when, emerging out of victory in World War II, the United States set out to remake both its own society and the world beyond it according to a tantalizing, but often problematic, notion of how it would feel to be free, what it might mean to keep cool but care.

To track the emergence of the so-called “Free World,” and what he believes to be its decline by the end of the 1960s, Louis Menand turns to dozens upon dozens upon dozens of biographical studies. He is particularly attuned to a kind of Zelig–like focus on supporters and connected participants as well as the obvious stars. We get the famous George Kennan, diplomat and framer of containment policy, but we also learn about Kennan’s mentors and colleagues, such as Robert Kelley, Charles “Chip” Bohlen, and other Soviet experts who shaped Kennan’s worldview.[4] We learn of the creative dialogue between painters Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, but also of the forgotten presence of Rachel Rosenthal, who was present at the moments of their artistic breakthroughs before going on to her own career as a performance artist.[5] Behind the circulation of American novels to France, and then French existentialism to the US, were translators such as Maurice-Edgar Coindreau and editors such as Gaston Guillimard.[6] We discover that Clement Greenberg’s infamous essay for the small magazine Partisan Review about abstract art, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” actually grew out of intensive collaboration with editor Dwight Macdonald, who in turn wrote about a very similar theme in his own essay “Masscult and Midcult.”[7] Instead of concentrating on Andy Warhol when examining the rise of Pop Art, Menand turns his attention to the British scene: the Independent Group, Eduardo Paolizzi, Nigel Henderson, Alison and Peter Smithson, Lawrence Alloway, and Richard Hamilton.[8] When it comes to film, we learn as much about the deep history of dynamics between Hollywood and Paris through the figures of Henri Langlois and André Bazin as we do about Truffaut and Godard.[9] Then we follow the hidden story of how writers Robert Benton and David Newman wrote the breakthrough Hollywood film Bonnie and Clyde with Truffaut in mind as a director. Menand stitches yet another thread around the tale by detailing how Bonnie and Clyde in turn made the career of influential film critic Pauline Kael.[10] Overall, in The Free World, we get a kind of Cold War mise en scène. The famous names are there, but Menand is much more interested in arranging for view the sets of people around or behind the typical protagonists of the tale. This is a book littered with such figures: editors, curators, translators, scenesters, lesser-known political advisors, and friends who made the free world something more than just a space of isolated actors.

For Menand, there were worlds within worlds within the “Free World,” and each grappled with freedom differently. Even within particular spheres, there were fierce disagreements. George Kennan, for instance, imagined his Cold War foreign policy concept of containment as practical, flexible, realistic. Then he was critiqued by Walter Lippmann and others who thought it became ideologically rigid. Kennan was horrified. He had intended containment to be realpolitik. As Menand ruefully points out at the end of The Free World, containment ultimately led to the quagmire of the American intervention in the Vietnam struggle for national independence, precisely the kind of conflict Kennan wanted the US to avoid.[11]

Many others—George Orwell, James Burnham, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, Hannah Arendt, Lionel Trilling, Norman Mailer, Susan Sontag, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Ira Berlin, James Baldwin, Franz Fanon, and Tom Hayden—continued these debates about politics, but increasingly the questions of containment and freedom also became dialogues about culture. What was actually existing freedom, not only politically but also personally? What was it not only in terms of policy, but also in terms of ideas, art, and lived experience? In the milieu of the visual arts, for instance, debates about representation, accuracy and their relationship to freedom raged as if they were as crucial as military maneuvers. Jackson Pollack, Lee Krasner, Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and others took turns making art, writing criticism, and framing approaches that addressed the relationship of reality and freedom, seeking not to contain things, as Kennan wanted to do with the Soviet Union and communism, but rather to emancipate the eye and mind from false perceptions.[12] Kerouac and the Beats as well as DT Suzuki and John Cage embraced aleatory chance and improvisational spontaneity as paths to freedom.[13] So too, in his way, did Elvis Presley and the 1950s teenagers who heard his music as liberating. This included the Beatles, who then joined the rock and roll parade, this “mass-market commercial product” exported transatlantically to Europe and back again to the US as a “hip and smart popular art form.”[14]

Overall, Menand seems content to leave one large argument aside for a panoply of smaller observations. Nonetheless, core themes surface. One is the arc of a global story about two ongoing sagas: the Cold War struggle between the US and the Soviet Union on the one hand, and the worldwide struggle for decolonization on the other. These come together in the Vietnam War, the event in which, according to Menand, “the two dominant geopolitical phenomena of the postwar period, the Cold War and decolonization, intersected.” For Menand, “Vietnam was a duck and a rabbit.”[15] Another theme is the fundamentally transatlantic nature of the “free world.” Repeatedly, a cultural or intellectual position about liberty and its possibilities or limits got catalyzed by circulation between the United States and Europe. In this way, The Free World is very much an Anglo-American intellectual and cultural history, with a bit of French élan sparkling through it.

Most of all, a concern throughout Menand’s book becomes not liberty itself but its opposite: Menand describes this flipside as a continual anxiety about totalitarianism during the era. “But what is totalitarianism?” Menand asks early on in his study. “How does it arise? Why are people drawn to it? Most important: Could it happen here?” For Menand, “People disagreed about how to answer the first three questions, and this made the last question an urgent one.”[16] In the aftermath of World War II, politics and culture merged in fears of totalitarianisms both obvious and subtle. President Harry S. Truman’s stark Truman Doctrine speech, delivered in 1947, proposed a dramatic choice between democratic freedom and undemocratic totalitarianism that extended from foreign affairs to social practices and intellectual frameworks. The speech, according to Menand, “had the same effect on art and thought as it did on government policy” by turning “intramural disputes into global ones.” This “made questions about value and taste, form and expression, theory and method into questions that bore on the choice between alternative ways of life.”[17] The Free World was, Menand’s book implies, also a world held prisoner by ongoing fears about the loss of freedom. Liberty always threatened to collapse into its opposite. This is, in its way, a Frankfurt School argument that itself rose to prominence during the Cold War. Like Herbert Marcuse, who makes a few cameos in the book, so too Menand is deeply aware of the ways in which Cold War freedoms often became covers for new types of control.

Joel Dinerstein’s book is also quite concerned with the fate of freedom and the question of control in the “Free World,” but instead of Menand’s capacious exploration of the concept, Dinerstein concentrates more squarely (and also with great hipness) on the sensibility of “cool.” He wants to trace how cool arose both out of an American and as a transatlantic response to economic depression, war, fascism, genocide, imperialism, decolonization, racism, and other horrors in the late 1940s and subsequent decades.

If Menand’s book is a labyrinthine affair about a burning intellectual and cultural debate concerning freedom, Dinerstein’s book is an exhaustive taxonomy of cooler efforts to achieve liberation. Like a jazz saxophonist improvising a solo over a set of changes, Dinerstein states and restates and restates again what cool was in the years after World War II. In endless variations, he offers myriad angles on and phrasings of his core argument, which is that cool, in the postwar era, became “synonymous with authenticity, independence, integrity, and nonconformity; to be cool meant you carried personal authority through a stylish mask of stoicism.”[18]

But that’s just one of many riffs Dinerstein offers. He goes on: “To call a person cool in the postwar era meant that there was some internal harmony about his or her artistic voice, style, and physical being.”[19] Cool was “an alternative success system combining wildness and composure.”[20] Cool was “a public mode of covert resistance.”[21] In a capitalist society, it expressed the inability to be owned even if one lacked material wealth.[22] To be cool “represented an inquiry into the reassessment of conventional morality outside of Christian frameworks and Western philosophical grandstanding” at a time when “modernity had triumphed but without covering its losses.”[23] It “signaled an underground search for an ethics to guide individuals into an era of post-Christian imperfectability.” Cool was “a transitional mask of composure necessary for those rebels who realized that Western civilization had come to an end, at least in its European phase.”[24] To be cool “was to project a calm defiance,” a “stylish Stoicism,” a “reptilian aplomb.”[25] It “marked a person out as an enemy of all propagandists,” “the valorization of the individual against larger dynamic forces” and became “a myth invested in the recuperation of individual agency.”[26] To be cool was to express “self-possession with one’s vulnerability just visible enough to show the emotional costs of the stance.”[27] It “concerned the potential for self-transformation through risk, introspection, transgression, and the romantic potential of an ideal bohemia.”[28] Cool was “rebellious, tough, independent, scornful of social convention.” It expressed “pride in class, ethnicity, and origins, and thus true to one’s roots within fame.” It involved “acting with integrity and style on a situational basis.”[29] Cool “was defiance with dignity.”[30] Cool was “a subconscious method of negotiating identity in modernity through popular culture.”[31] For Dinerstein, “under the sign of cool, the rebel was reframed as a productive critic of society.”[32] These are just a few of Dinerstein’s definitions of the phenomenon of cool.

Despite the many incarnations that Dinerstein notices, he does not view the idea of cool as a “transhistorical concept.”[33] The stance of what Dinerstein describes as “relaxed intensity” arose from a particular “convergence of African-American and Anglo-American archetypal modes of masculinist behavior” in the postwar era.[34] There was the long-running aesthetic and cultural ideal of cool that arrived in the New World from West African cultures by way of the Black diaspora.[35] In these contexts, “cool” signaled a restoration of social order and community.[36] At the same time, there was the stiff upper lip of the upper-class gentleman found in Victorian Britain, a mode of restraint celebrated by no less a figure than Duke Ellington, who praised the English as possessing a “sense of balance.”[37] This style gave way in the twentieth century, however, to the “tough loner” of the working-class American city (think of the shift in crime fiction from Sherlock Holmes and Watson to hard-boiled “tough loners” such as gumshoe detectives Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe).[38]

These modes of cool served as resources for the postwar development of the style. For Dinerstein, cool only emerged in full with African-American figures such as the jazz saxophonist Lester Young, who, as jazz critic Ben Sidran put it, expressed a highly individualized “actionality turned inward” with his musical style as well as his in whole persona.[39] Young’s story, which Dinerstein tells in wonderful detail, demonstrates the central place of African-American culture in the postwar concept of cool. Young and others African-Americans transmuted the traumas not only of World War II, but also of the Middle Passage, slavery, and Jim Crow into brilliantly eccentric individual styles that also always contained the seeds of collective resistance.[40] The African-American mode of cool developed by Young and passed along to the likes of Charles Parker, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, and others came together with multiracial working-class investments in stylized rebellion, particularly among young men. And, as Dinerstein notes, with figures such as Billie Holiday, Simone de Beauvoir, Carole Cutrere (Woodward), and Lorraine Hansberry, a feminist approach appeared as well. Cool ultimately became, Dinerstein writes, an “emergent structure of feeling in postwar America,” the “hidden transcript of the postwar era.”[41]

Expertly unearthing these archeological layers, Dinerstein contends that their shared goal was to achieve the “syncretism of a cross-cultural mask of cool” (122) that was dedicated to “self-authorizing” (170). Cool was an assertion of individual existence in the face of systems that sought to erase, deface, ignore, dissolve, dismiss, or destroy the self. From here we get, according to Dinerstein, many forms and many faces of cool: the hardboiled skepticism of Hollywood noir, expressed by figures such as Bogart, Mitchum, Veronica Lake, and Barbara Stanwyk; the “existential cool” of Camus, Beauvoir, Sartre, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, and James Baldwin; the interest in a more multicultural American cool in the writings of the often-misinterpreted French-Canadian Beat novelist Jack Kerouac; the more emotional cinematic approaches of Brando and Dean; and the variations on cool expressed by Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Johnny Cash, Sterling Hayden, Paul Newman, and many others.

Intriguingly, and I think successfully, Dinerstein makes a fine-grained distinction between what he chronologizes as a Postwar I era of cool from 1945 to 1952 and a Postwar II from 1953 to 1963, split by the key event of the Korean War. The first phase emphasized “dignity within limits, a calm defiance against authority with little expectation of social change” while the later “inflected toward a certain wild abandon, a bursting of emotional seams reflecting a hopeful surge against obsolete social conventions.”[42] In this way, Dinerstein wants to argue that “cool is a matrix that changes according to generational desire.”[43] As the “makeshift period of recovery from war, social instability, and trauma” gave way to “a period of extensive middle-class prosperity and American triumphalism masking the underlying tensions of the Cold War,” an “anxious phase of instability and readjustment” was followed by a “slow-breaking prosperity” that “registered a new cohort of teenagers” and their cultural desires.[44] In short, the resigned, tense cool of Bogart, Bacall, Sinatra, and Mitchum gave way to “their seeming opposites” in Kerouac, Brando, Dean, and Elvis, who were much more expansive in their emotional expressivity.[45] What was cool in the first phase of the postwar era, a certain kind of internalized numbness, shifted after the Korean War into an embrace of externalized vulnerability.

The danger to Dinerstein’s approach in tracking cool’s many variations is that cool might become anything and everything in the postwar period. When are we talking about some other cultural formation or concept? At what point does cool turn vague? Thankfully, Dinerstein’s attunement to specific source material cools this potential interpretive crisis. He is content to leave aside other modes of postwar culture that might be cool-adjacent. For instance, there is no focus on camp style in the book. Susan Sontag makes no appearance, nor do figures such as Andy Warhol. Instead, in covering the careers of Young, Davis, Bogart, Mitchum, Lake, Stanwyck, Camus, Holiday, Beauvoir, Kerouac, Sinatra, Brando, Dean, Presley, Rollins, Newman, Poitier, Cutrere (Woodward), and Hansberry, not to mention dozens of other cool characters, Dinerstein shows us the subtler ways in which cool shifted in and out of the shadows of postwar life. Below the mushroom cloud, the cool cats.

Because Menand wants to glimpse the white-hot explosion of interest in freedom during the Cold War decades while Dinerstein concentrates on what became cool, what results from their books are almost opposite rhetorical styles. But the opposition is not what one would think. It is Menand who plays it cool and Dinerstein who sometimes gets a bit too excited. Menand provides a kaleidoscopic tour of the postwar era. He sees no need for coordinated contentions or consistent interpretive positions. He coolly insists, instead, on retaining his authorial freedom to explore the so-called Free World without containing it in a sole thesis. He declines to articulate a polemic, or even a particularly strong central argument. Dinerstein, by contrast, overdoes it sometimes with his circles upon circles of cool definitions. Unlike Menand’s quiet approach, he delivers a kind of roaring extended solo with a recurring point: here, there, everywhere we see the mask of cool appear and reappear as a mode of expressing collective rebellion in distinctive, individualized manifestations. Yet what keeps his book from getting too wild is Dinerstein’s capacity for masterful close analysis of specific artifacts. This makes for supremely cool cultural history even as Dinerstein sometimes has trouble tamping down his enthusiasm for the material.

Do these two books have straight, white man problems? Yes. How uncool! Both books tilt toward emphasizing normative masculinist dimensions of postwar culture. That said, Menand and Dinerstein do make efforts to widen the lens a bit. But only a bit. For example, Menand is attuned to the women obscured from view by the misogyny of the postwar era. These are figures who actually shaped the free world in decisive ways despite their roles as editors, curators, wives, and supporters. Despite sexism, unfree bystanders they were not. Similarly, Dinerstein notes the need for a full study of postwar female cool that might include not only his emphasis on Billie Holiday, Simone de Beauvoir, and a few other key figures, but also more extended examination of Anita O’Day, Bettie Page, Patricia Highsmith, Lena Horne, Dinah Washington, Abbey Lincoln, Gloria Graham, Veronica Lake, and Ida Lupino.[46] One might also ask if gay culture was more crucial to the Cold War years than either Menand or Dinerstein acknowledge. So too, one might wonder if ethnic variations on freedom and cool are important to address more intently within the United States, or if a more global rather than primarily transatlantic one is required. Menand’s treatments of the careers of Aimé Césaire and Franz Fanon as well as his attention to Richard Wright’s presence at the 1955 Bandung conference prove quite tantalizing in their moves toward a more far-reaching worldwide study of the free and the cool in Cold War life.[47] No book, even big ones like these, can do everything. Despite their imperfections, The Free World and The Origins of Cool in Postwar America are utterly engrossing historical smorgasbords that add much to existing studies of postwar US culture.[48]

But what do Menand and Dinerstein’s extensive investigations add up to in the end?

If we can say there is an overarching point to Menand’s book, it is that freedom dominated the postwar decades not as an achieved result, but rather as a nagging dream. In The Free World, the Free World was hamstrung by ongoing anxieties that fascism might rear its beastly head again, that the damaging dehumanizations of colonialism could not be undone, or, most worryingly of all, that totalitarianism might sneak in through the back door, disguised by the very emancipatory desires it sought to destroy, as demands for liberty busted the front wide open. For Dinerstein, cool became one way to respond to the pressures—and oppressive failures—to achieve freedom in the Free World. The cool solution was not to confront totalitarianism so much as to survive it through various tactics of deflection. The many figures in Menand’s book could be said to have tried, overall, to unmask totalitarianism, to show that the emperor had no clothes. The many in Dinerstein’s book (even when they are sometimes the very same ones that Menand mentions) could be said to have done just the opposite: they masked up, finding new disguises to subvert totalitarian’s drive to control or annihilate them.

The wide-ranging explorations by both authors therefore put pressure on the thesis put forward recently by Casey Blake, Daniel Borus, and Howard Brick that the Cold War era might be best characterized as a period of “centering.”[49] For Menand and Dinerstein, the devil is in the details and there, in the many people and events they examine, we discover numerous troublemakers interested more in their own specific approaches to liberation (or sometimes just survival) than in a coherent, unified, core path to freedom for all. In these two studies, Cold War culture was a dizzying fractal, not a consolidated consensus. Postwar culture in—and beyond—America was far more pluribus than unum.

[1] Louis Menand, The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), xii.

[2] Langston Hughes, “Motto” (1951), quoted in Joel Dinerstein, The Origins of Cool in Postwar America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 23.

[3] Thomas Pynchon, V. (New York: JB Lippincott & Co, 1963), 366.

[4] Menand, 11.

[5] Menand, 263.

[6] Menand, 75-76.

[7] Menand, 128.

[8] Menand, 433-440.

[9] Menand, 648.

[10] Menand, 662-685.

[11] Menand, 26.

[12] Menand, 122-156; 227-271.

[13] Menand, 179-183; 235-259.

[14] Menand, 332.

[15] Menand, 721.

[16] Menand, 6.

[17] Menand, 6.

[18] Dinerstein, 5.

[19] Dinerstein, 4.

[20] Dinerstein, 7.

[21] Dinerstein, 14.

[22] Dinerstein, 19.

[23] Dinerstein, 18.

[24] Dinerstein, 28.

[25] Dinerstein, 9, 17. 24.

[26] Dinerstein, 25, 26.

[27] Dinerstein, 180.

[28] Dinerstein, 268.

[29] Dinerstein, 303.

[30] Dinerstein, 356.

[31] Dinerstein, 441.

[32] Dinerstein, 348.

[33] Dinerstein, 14.

[34] Dinerstein, 8.

[35] On the African origins of cool, see Robert Farris Thompson, “An Aesthetic of the Cool: West African Dance,” African Forum, 2, 2 (Fall 1966): 85-102; “An Aesthetic of Cool,” African Arts 7, 1 (Fall 1973): 40-43, 64-67, 89-91; Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit (New York: Vintage, 1984); and Aesthetic of the Cool: Afro-Atlantic Art and Music, 2011).

[36] Dinerstein, 54.

[37] Dinerstein, 8.

[38] Dinerstein, 8.

[39] Dinerstein, 37.

[40] Dinerstein, 37-70.

[41] Dinerstein, 34, 19.

[42] Dinerstein, 13-14.

[43] Dinerstein, 310.

[44] Dinerstein, 14, 13.

[45] Dinerstein, 14, 13.

[46] Dinerstein, 184.

[47] Menand, 397-421.

[48] See, among others, W. T. Lhamon, Jr., Deliberate Speed: The Origins of a Cultural Style in the American 1950s, with a New Preface (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990; 2nd edition, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002); George Cotkin, Existential America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003; George Cotkin, Feast of Excess: A Cultural History of the New Sensibility (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); Robert Genter, Late Modernism: Art, Culture, and Politics in Cold War America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011); Grace Elizabeth Hale, A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); Kevin Mattson, Rebels All!: A Short History of the Conservative Mind in Postwar America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008), Leerom Medovoi, Rebels: Youth and the Cold War Origins of Identity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005); Robert J. Corber, Homosexuality in Cold War America: Resistance and the Crisis of Masculinity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997); Paul Boyer, By the Bomb’s Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985); Stephen J. Whitfield, The Culture of the Cold War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996); Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 1988); Lary May, ed., Recasting America: Culture and Politics in the Age of Cold War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989).

[49] Casey Nelson Blake, Daniel H. Borus, and Howard Brick, At the Center: American Thought and Culture in the Mid-Twentieth Century (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2020).