Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 13

October 12, 2023

Public History Infrastructure as a Public Educational Resource

Print of Clio, made in the 16th–17th century.

Print of Clio, made in the 16th–17th century.Notes for talk about the goals of the SUNY HistoryLab pilot project at the Teaching & Learning Through Digital Public History Projects panel of the 2023 SUNY OER Summit.

Part of our jobs as SUNY faculty who study the past is to create new historical knowledge, but we are not harnessing this part of our work as effectively as we could for public use.Rather than think of OER as the abandonment of public education for private, edtech solutionism, what if we rethought OER as building infrastructure within the SUNY system, in disciplines and areas of research and teaching that we have expertise in, and in putting resources toward being able to deliver better the public value of faculty expertise in research and teaching for public use.That’s the idea behind the SUNY HistoryLab, which we are piloting this year through an Innovative Instruction Technology Grant.The goal of the SUNY HistoryLab is to build, piece by piece, a scholarly network focused on historical inquiry, first across SUNY campuses and then with key partners in the state as a whole.It’s an ambitious idea, but one that, if built piece by piece through piloting and experimentation, might serve as more of an in-system approach to OER—or PER as I prefer to call it, Public Educational Resources.First, to develop the SUNY Historylab, we realized that before we can deliver faculty knowledge and expertise to institutions and citizens of the state, we have to construct a more robust scholarly network within the very decentralized SUNY system. So our first step is to create places for scholarly exchange about historical inquiry. Rather than pit campuses against each other, how might we foster connections among those exploring the past to exchange research, teaching ideas, and possibilities for cross-campus projects? In service of deepening the capacities of SUNY to connect faculty expertise to the public of New York State, step one of the SUNY HistoryLab to create a regular webinar for presentations and exchange about historical inquiry in the system as well as a website and listserv for further interaction. This will take time to develop and figure out, not just technically, but also institutionally. How do we balance the broader disciplinary questions of historical inquiry with subfields based on region, time period, and methodologies of historical research? How do we distribute possibilities effectively across campuses? How do we sustain the HistoryLab as a cross-campus, system-wide virtual SUNY laboratory for historical inquiry?What then? A SUNY virtual history laboratory is worth doing and could serve as a model of discipline oriented system-wide infrastructure for improving research and exchange among faculty and interested students. That’s great in of itself I believe.But how do we then make it more OER, or as I prefer, PER—a public educational resource?The second goal of our Innovative Instruction Technology Grant is to pilot the HistoryLab as a place that can digitally curate SUNY faculty historical research for effective public use? What would it take to be able to create digital modules that translate SUNY historical research and teaching expertise for K-12 education, for museums and libraries and other public institutions in the state, for municipalities and nonprofits (say a town celebrating a particular event, or seeking more knowledge of a new immigrant population in their town), even for use by for-profit businesses seeking historical knowledge for their work (a bookstore seeking to build an in-store program for instance)? Here’s a challenge, but alas an opportunity: to build better institutional relationships across education and public history in the state. SUNY historians can join with other experts—expertise among K-12 educators, museum professionals, and the knowledge of everyday citizens who think about the past—to foster a richer world of historical inquiry in the state. In this way SUNY could become a key part of a broader public project of investigating, exploring, and understanding the past as an essential part of grappling with the present in service of the future. This is, to be sure, a bit about dissemination of knowledge, but more crucially it is ultimately about forging partnerships for the study of the past—precisely the kinds of approaches and models of shared authority and collective inquiry between people and institutions that public history as a field has contributed to developing.For SUNY itself, the HistoryLab also becomes a potential pedagogical tool: how might we even involve SUNY students in this work of public curation of faculty research?Indeed, creating digital modules of historical inquiry for public use becomes a promising training ground for teaching core skills of information literacy, digital fluency, historical understanding, research abilities, writing and communication effectiveness, and project management. The result, if we could develop a sustainable SUNY HistoryLab, could be a richer world of specialized SUNY historical research, more exchange for faculty and students in the SUNY system, new kinds of pedagogical opportunities, and a stitching of the research parts of SUNY historian jobs to the public value of the SUNY system as a whole for citizens of the state: we could, if we build it right and with support, deliver cutting-edge historical understanding in accessible forms to institutions of the state such as schools, libraries, museums, historical societies, interest groups, municipalities, nonprofits, and businesses—and really as a public good for any citizen interested in history.It’s an ambitious idea, but one that might translate to other disciplines alongside history: literary studies, social sciences, environmental work, natural sciences. The university is structured by these disciplines. We might use that structuring to expand the public value of what we do in our respective fields. From that disciplinary work also, potentially, comes new opportunities for inter-disciplinary work. With investment in infrastructure, most especially people, all the areas of research at SUNY could be more effectively shared with as valuable educational resources for public use: for individual edification; education; expanded community knowledge, resilience, and health; even job development—and for the overarching public good of the state of New York.12 October 2023—Teaching & Learning Through Digital Public History Projects

Notes for talk about the goals of the SUNY HistoryLab pilot project at the Teaching & Learning Through Digital Public History Projects panel of the 2023 SUNY OER Summit.

Part of our jobs as SUNY faculty who study the past is to create new historical knowledge, but we are not harnessing this part of our work as effectively as we could for public use.Rather than think of OER as the abandonment of public education for private, edtech solutionism, what if we rethought OER as building infrastructure within the SUNY system, in disciplines and areas of research and teaching that we have expertise in, and in putting resources toward being able to deliver better the public value of faculty expertise in research and teaching for public use.That’s the idea behind the SUNY HistoryLab, which we are piloting this year through an Innovative Instruction Technology Grant.The goal of the SUNY HistoryLab is to build, piece by piece, a scholarly network focused on historical inquiry, first across SUNY campuses and then with key partners in the state as a whole.It’s an ambitious idea, but one that, if built piece by piece through piloting and experimentation, might serve as more of an in-system approach to OER—or PER as I prefer to call it, Public Educational Resources.First, to develop the SUNY Historylab, we realized that before we can deliver faculty knowledge and expertise to institutions and citizens of the state, we have to construct a more robust scholarly network within the very decentralized SUNY system. So our first step is to create places for scholarly exchange about historical inquiry. Rather than pit campuses against each other, how might we foster connections among those exploring the past to exchange research, teaching ideas, and possibilities for cross-campus projects? In service of deepening the capacities of SUNY to connect faculty expertise to the public of New York State, step one of the SUNY HistoryLab to create a regular webinar for presentations and exchange about historical inquiry in the system as well as a website and listserv for further interaction. This will take time to develop and figure out, not just technically, but also institutionally. How do we balance the broader disciplinary questions of historical inquiry with subfields based on region, time period, and methodologies of historical research? How do we distribute possibilities effectively across campuses? How do we sustain the HistoryLab as a cross-campus, system-wide virtual SUNY laboratory for historical inquiry?What then? A SUNY virtual history laboratory is worth doing and could serve as a model of discipline oriented system-wide infrastructure for improving research and exchange among faculty and interested students. That’s great in of itself I believe.But how do we then make it more OER, or as I prefer, PER—a public educational resource?The second goal of our Innovative Instruction Technology Grant is to pilot the HistoryLab as a place that can digitally curate SUNY faculty historical research for effective public use? What would it take to be able to create digital modules that translate SUNY historical research and teaching expertise for K-12 education, for museums and libraries and other public institutions in the state, for municipalities and nonprofits (say a town celebrating a particular event, or seeking more knowledge of a new immigrant population in their town), even for use by for-profit businesses seeking historical knowledge for their work (a bookstore seeking to build an in-store program for instance)? Here’s a challenge, but alas an opportunity: to build better institutional relationships across education and public history in the state. SUNY historians can join with other experts—expertise among K-12 educators, museum professionals, and the knowledge of everyday citizens who think about the past—to foster a richer world of historical inquiry in the state. In this way SUNY could become a key part of a broader public project of investigating, exploring, and understanding the past as an essential part of grappling with the present in service of the future. This is, to be sure, a bit about dissemination of knowledge, but more crucially it is ultimately about forging partnerships for the study of the past—precisely the kinds of approaches and models of shared authority and collective inquiry between people and institutions that public history as a field has contributed to developing.For SUNY itself, the HistoryLab also becomes a potential pedagogical tool: how might we even involve SUNY students in this work of public curation of faculty research?Indeed, creating digital modules of historical inquiry for public use becomes a promising training ground for teaching core skills of information literacy, digital fluency, historical understanding, research abilities, writing and communication effectiveness, and project management. The result, if we could develop a sustainable SUNY HistoryLab, could be a richer world of specialized SUNY historical research, more exchange for faculty and students in the SUNY system, new kinds of pedagogical opportunities, and a stitching of the research parts of SUNY historian jobs to the public value of the SUNY system as a whole for citizens of the state: we could, if we build it right and with support, deliver cutting-edge historical understanding in accessible forms to institutions of the state such as schools, libraries, museums, historical societies, interest groups, municipalities, nonprofits, and businesses—and really as a public good for any citizen interested in history.It’s an ambitious idea, but one that might translate to other disciplines alongside history: literary studies, social sciences, environmental work, natural sciences. The university is structured by these disciplines. We might use that structuring to expand the public value of what we do in our respective fields. From that disciplinary work also, potentially, comes new opportunities for inter-disciplinary work. With investment in infrastructure, most especially people, all the areas of research at SUNY could be more effectively shared with as valuable educational resources for public use: for individual edification; education; expanded community knowledge, resilience, and health; even job development—and for the overarching public good of the state of New York.September 30, 2023

Rovings

Ed Clark, North Light (Paris), 1987.SoundsSusie Ibarra, Talking GongWGXC Afternoon Show: Susie Ibarra, 30 September 2023Claire Chase, Density 2036, Parts I-VIIISufjan Stevens, JavelinJoni Mitchell with Neil Young and the Stray Gators, “You Turn Me On (I’m a Radio),” Archives, Vol. III: The Asylum YearsJoni Mitchell, “You Turn Me On (I’m a Radio)” (Live), Miles of AislesJoni Mitchell, “You Turn Me On (I’m a Radio),” For the RosesKalanduyan Family, The Cotabato SessionsSteve Roden Tribute, Framework Radio # 859, 24 September 2023Steve Roden, Framework Radio # 858, 17 September 2023Titanic, “Vidrio”Yasmin Williams, “Dawning”Organizing and Socialist Strategy, The Dig, 22 September 2023Conjuncture with Akbar, Winant, & Riofrancos, The Dig, 13 August 2023Emergent Terrain with Akbar, Winant, & Riofrancos, The Dig, 24 August 2023WordsKirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century AmericaJeremy Gordon, “The evolution of Steve Albini: ‘If the dumbest person is on your side, you’re on the wrong side’,” The Guardian, 15 August 2023Sean Michels, “Chat’s Entertainment: ChatGPT and the coming blandification of AI,” The Baffler, 24 August 2023 Dave Mandl, “North Korea on the Hudson: On Alexander Stille’s The Sullivanians,” LARB, 9 September 2023Fred Harrison, “Gronlund and Other Marxists,” American Journal of Economics & Sociology 62, 5 (November 2003): 259–96Max Nelson, “A Marx for All Seasons: Ben Tarnoff, interviewed by Max Nelson,” New York Review of Books Blog, 16 September 2023Michael Koncewicz, “A Postcard from Ann Arbor, Michigan,” Contingent Magazine, 20 September 2023Henry Threadgill Interview with David Hershkovits, Brooklyn Rail, September 2023“Walls”Anselm Kiefer, Finnegans Wake @ White Cube, Bermondsey, LondonPepón Osorio, My Beating Heart/Mi corazón latiente @ New MuseumErika Verzutti, New Moons @ Hessel Museum of ArtRomuald Hazoumè, The Fâ Series @ The Neuberger MuseumVisual Vernaculars @ MoMAEd Clark @ Hauser & Wirth NYCVivian Suter @ Gladstone GallerySam Gilliam, The Last Five Years @ Pace GalleryAllan Sekula, Fish Story @ Walker Art CenterChristian Marclay, Doors @ White Cube Mason’s YardsKomar & Melamid, The Most Wanted Paintings on the Web @ DIA Art“Stages”Eugene Chadbourne @ Bop Shop Records, 12 September 2023Leïla Ka, Pode Ser @ Rochester Fringe Festival, Sloan Performing Arts Center, University of Rochester, 15 September 2023Cirque Inextremiste, EXIT @ Rochester Fringe Festival, Parcel 5, 16 September 2023Heather Roffe Dance, Human Resources @ Rochester Fringe Festival, School of the Arts, 16 September 2023The Rise and Fall of Affirmative Action: The 2023 Hutchins Forum @ Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, 17 August 2023Critical Materials: Centering Latin America in Global Supply Chains @ Americas Society/Council of the Americas, 20 July 2023Chilean Artists in New York: Sylvia Palacios Whitman, Cecilia Vicuña, Marcelo Montealegre @ Arts in the Americas Society, 19 July 2023Melanie R. Hill, Teaching with Transformative Texts: Morrison and Music, 28 September 2023 @ Teagle FoundationScreensNancy Buchanan, California StoriesThe GeneralNotorious

Ed Clark, North Light (Paris), 1987.SoundsSusie Ibarra, Talking GongWGXC Afternoon Show: Susie Ibarra, 30 September 2023Claire Chase, Density 2036, Parts I-VIIISufjan Stevens, JavelinJoni Mitchell with Neil Young and the Stray Gators, “You Turn Me On (I’m a Radio),” Archives, Vol. III: The Asylum YearsJoni Mitchell, “You Turn Me On (I’m a Radio)” (Live), Miles of AislesJoni Mitchell, “You Turn Me On (I’m a Radio),” For the RosesKalanduyan Family, The Cotabato SessionsSteve Roden Tribute, Framework Radio # 859, 24 September 2023Steve Roden, Framework Radio # 858, 17 September 2023Titanic, “Vidrio”Yasmin Williams, “Dawning”Organizing and Socialist Strategy, The Dig, 22 September 2023Conjuncture with Akbar, Winant, & Riofrancos, The Dig, 13 August 2023Emergent Terrain with Akbar, Winant, & Riofrancos, The Dig, 24 August 2023WordsKirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century AmericaJeremy Gordon, “The evolution of Steve Albini: ‘If the dumbest person is on your side, you’re on the wrong side’,” The Guardian, 15 August 2023Sean Michels, “Chat’s Entertainment: ChatGPT and the coming blandification of AI,” The Baffler, 24 August 2023 Dave Mandl, “North Korea on the Hudson: On Alexander Stille’s The Sullivanians,” LARB, 9 September 2023Fred Harrison, “Gronlund and Other Marxists,” American Journal of Economics & Sociology 62, 5 (November 2003): 259–96Max Nelson, “A Marx for All Seasons: Ben Tarnoff, interviewed by Max Nelson,” New York Review of Books Blog, 16 September 2023Michael Koncewicz, “A Postcard from Ann Arbor, Michigan,” Contingent Magazine, 20 September 2023Henry Threadgill Interview with David Hershkovits, Brooklyn Rail, September 2023“Walls”Anselm Kiefer, Finnegans Wake @ White Cube, Bermondsey, LondonPepón Osorio, My Beating Heart/Mi corazón latiente @ New MuseumErika Verzutti, New Moons @ Hessel Museum of ArtRomuald Hazoumè, The Fâ Series @ The Neuberger MuseumVisual Vernaculars @ MoMAEd Clark @ Hauser & Wirth NYCVivian Suter @ Gladstone GallerySam Gilliam, The Last Five Years @ Pace GalleryAllan Sekula, Fish Story @ Walker Art CenterChristian Marclay, Doors @ White Cube Mason’s YardsKomar & Melamid, The Most Wanted Paintings on the Web @ DIA Art“Stages”Eugene Chadbourne @ Bop Shop Records, 12 September 2023Leïla Ka, Pode Ser @ Rochester Fringe Festival, Sloan Performing Arts Center, University of Rochester, 15 September 2023Cirque Inextremiste, EXIT @ Rochester Fringe Festival, Parcel 5, 16 September 2023Heather Roffe Dance, Human Resources @ Rochester Fringe Festival, School of the Arts, 16 September 2023The Rise and Fall of Affirmative Action: The 2023 Hutchins Forum @ Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, 17 August 2023Critical Materials: Centering Latin America in Global Supply Chains @ Americas Society/Council of the Americas, 20 July 2023Chilean Artists in New York: Sylvia Palacios Whitman, Cecilia Vicuña, Marcelo Montealegre @ Arts in the Americas Society, 19 July 2023Melanie R. Hill, Teaching with Transformative Texts: Morrison and Music, 28 September 2023 @ Teagle FoundationScreensNancy Buchanan, California StoriesThe GeneralNotorious

September 24, 2023

Barry Olivier, 1935-2023

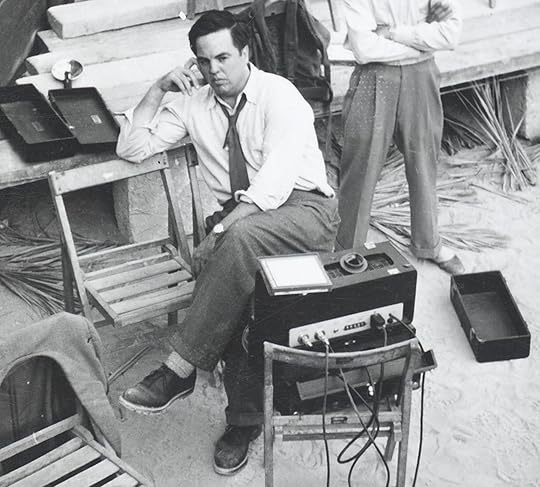

Barry Olivier addressing the crowd at the 1964 Berkeley Folk Music Festival opening concert in the Faculty Glade. He created and directed the Berkeley Folk Music Festival from 1958 to 1970.

Barry Olivier addressing the crowd at the 1964 Berkeley Folk Music Festival opening concert in the Faculty Glade. He created and directed the Berkeley Folk Music Festival from 1958 to 1970. The Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project is sad to report the death of Barry Olivier, 1935-2023. Without Barry, no Berkeley Folk Music Festival. He was the director and guiding spirit from 1958 to 1970, and this was just one part of a life well lived.

Barry had a calm, quietly caring spirit, but could then burst into one of the best, most garrulous laughs on the planet. He was a fine singer and guitar picker, an exquisite organizer (the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive bears this out), and someone who just simply made the world a better place.

Barry Olivier, right, with Sam Hinton, the master of ceremonies at all of the Berkeley Folk Music Festivals, in 1964 at the Jackson Hole Folk Festival, another event that Olivier organized and directed.

Barry Olivier, right, with Sam Hinton, the master of ceremonies at all of the Berkeley Folk Music Festivals, in 1964 at the Jackson Hole Folk Festival, another event that Olivier organized and directed.When I first contacted Barry about digitizing the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive, which had sat mostly unused at Northwestern University’s Special Collections Library for decades, he immediately supported the idea. “Oh,” he said, “it can be a continuation of what we were trying to do at the Festival.” We settled on the concept of thinking of the project as a “digital river of song” that could try to carry the best energies of the original Festival into the online world. And just as he did at the original event, Barry was so solid in his support of the effort to push forward the online extension of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

What a wonderful guy. Many of us will miss him dearly. We send condolences to the entire Olivier family and to Barry’s wife Alice. More celebrations of Barry’s life and work to come. For more about Barry Olivier’s time as creator and director of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, visit the digital exhibit, The Berkeley Folk Music Festival & the Folk Revival on the US West Coast—An Introduction.

September 19, 2023

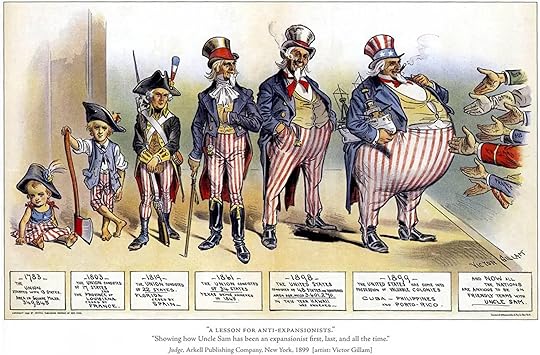

The Transatlantic Ballad of Alan Lomax

Studying vocal performance styles during his time in Europe during the 1950s, the US ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax (1915-2002) transformed his regionalist approach to folk songs into a global framework. His “Cantometrics” and “Global Jukebox” projects show how a “reverse” transatlantic experiences can produce transnational maps of song and culture. A new multimedia essay published at Transatlantic Cultures.

August 31, 2023

Rovings

Juan Francisco Elso, Por América (José Martí), 1986. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.Sounds“Brain: The First Personal Computer Virus,” Witness History, BBC Sounds, 25 July 2023Hazel V. Carby and Adam Shatz, “The Colour Line in the Americas,” LRB Podcast, 12 January 2021Surv

ey of Traditional Music, Vol. 1: From British Tradition

Survey of Traditional Music, Vol. 2: A Musical Melting Pot

Survey of Traditional Music, Vol. 3: Songs of Melancholy and Sorrow

Survey of Traditional Music, Vol. 4: The Anglo-African Exchange

Survey of Traditional Music, Vol. 5: Grown on American Soil

Eric Donaldson, Eric Donaldson Sings 20 Jamaica ClassicsPeter Tosh, Live at My Father’s Place 1978Peter Tosh, Live and Dangerous: Boston 1976WordsJoanna Pocock, “A beautiful, broken America: what I learned on a 2,800-mile bus ride from Detroit to LA,” The Guardian, 26 July 2023Tarnoff, Ben. “Weizenbaum’s Nightmares: How the Inventor of the First Chatbot Turned against AI.” Guardian, 25 July 2023David Waldstreicher, “Who Is History For? What happens when radical historians write for the public,” Boston Review, 25 July 2023Paula Cocozza, “Married to the mob: the rise of the smartphone in fiction,” The Guardian, 22 July 2023Colson Whitehead, The Colossus of New YorkTodd Cronan and Charles Palermo, “Can a White Curator Do Justice to African Art? Behind the scenes at the New Orleans Museum of Art,” The Nation, 11 August 2023Marcia Chatelain, “Tens of Millions: The persistence of American poverty,” The Nation, 21 August 2023Elif Batuman, The IdiotKazuo Ishiguro, The Buried GiantVisual Studies Workshop Salon Review, Fall 2023“Walls”Juan Francisco Elso: Por América @ Phoenix Art MusuemSilke Otto-Knapp @ Regen ProjectsCrafting Radicality: Bay Area Artists from the Svane Gift @ de Young MuseumWhat Has Been and What Could Be: The BAMPFA Collection @ BAMPFAMATRIX 282 / Griselda Rosas: Yo te cuido @ BAMPFADuane Linklater: mymothersside @ BAMPFARagnar Kjartansson: The Visitors @ SFMoMAHung Liu: Witness @ SFMoMAAfterimages: Echoes of the 1960s from the Fisher and SFMOMA Collections @ SFMoMA“Stages”Build as We Fight: The Revolutionary Legacy of James and Grace Lee Boggs @ ASA 2019, 17 January 2020John Szwed discussing the life and work of Harry Smith @ CityLights Bookstore, 23 August 2023ScreensWayne Shorter: Zero GravityAnna Bella Geiger, Passagens 1Sacco & Vanzetti, dir. Peter MillerUmm Kulthum: A Voice Like Egypt

Juan Francisco Elso, Por América (José Martí), 1986. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.Sounds“Brain: The First Personal Computer Virus,” Witness History, BBC Sounds, 25 July 2023Hazel V. Carby and Adam Shatz, “The Colour Line in the Americas,” LRB Podcast, 12 January 2021Surv

ey of Traditional Music, Vol. 1: From British Tradition

Survey of Traditional Music, Vol. 2: A Musical Melting Pot

Survey of Traditional Music, Vol. 3: Songs of Melancholy and Sorrow

Survey of Traditional Music, Vol. 4: The Anglo-African Exchange

Survey of Traditional Music, Vol. 5: Grown on American Soil

Eric Donaldson, Eric Donaldson Sings 20 Jamaica ClassicsPeter Tosh, Live at My Father’s Place 1978Peter Tosh, Live and Dangerous: Boston 1976WordsJoanna Pocock, “A beautiful, broken America: what I learned on a 2,800-mile bus ride from Detroit to LA,” The Guardian, 26 July 2023Tarnoff, Ben. “Weizenbaum’s Nightmares: How the Inventor of the First Chatbot Turned against AI.” Guardian, 25 July 2023David Waldstreicher, “Who Is History For? What happens when radical historians write for the public,” Boston Review, 25 July 2023Paula Cocozza, “Married to the mob: the rise of the smartphone in fiction,” The Guardian, 22 July 2023Colson Whitehead, The Colossus of New YorkTodd Cronan and Charles Palermo, “Can a White Curator Do Justice to African Art? Behind the scenes at the New Orleans Museum of Art,” The Nation, 11 August 2023Marcia Chatelain, “Tens of Millions: The persistence of American poverty,” The Nation, 21 August 2023Elif Batuman, The IdiotKazuo Ishiguro, The Buried GiantVisual Studies Workshop Salon Review, Fall 2023“Walls”Juan Francisco Elso: Por América @ Phoenix Art MusuemSilke Otto-Knapp @ Regen ProjectsCrafting Radicality: Bay Area Artists from the Svane Gift @ de Young MuseumWhat Has Been and What Could Be: The BAMPFA Collection @ BAMPFAMATRIX 282 / Griselda Rosas: Yo te cuido @ BAMPFADuane Linklater: mymothersside @ BAMPFARagnar Kjartansson: The Visitors @ SFMoMAHung Liu: Witness @ SFMoMAAfterimages: Echoes of the 1960s from the Fisher and SFMOMA Collections @ SFMoMA“Stages”Build as We Fight: The Revolutionary Legacy of James and Grace Lee Boggs @ ASA 2019, 17 January 2020John Szwed discussing the life and work of Harry Smith @ CityLights Bookstore, 23 August 2023ScreensWayne Shorter: Zero GravityAnna Bella Geiger, Passagens 1Sacco & Vanzetti, dir. Peter MillerUmm Kulthum: A Voice Like Egypt

August 20, 2023

Syllabus—Public History

Jefferson Davis Memorial, Monument Avenue, Charlottesville, Virginia, with Vindicatrix statue and Black Lives Matter graffiti, 2020. Fannie Barrier Williams, Brockport resident and Black antiracist, feminist activist, ca. 1880.

What are we up to?This synchronous, undergraduate/graduate, online/in-person course introduces students to public history: how it connects specialized scholarship to different audiences; how it asks all participants to share historical authority across multiple perspectives; how it raises questions of contested memory, heritage, and tradition; how history manifests in monuments, museums, performances, and displays and spaces found in everyday life; how it involves diverse forms of research, writing, communication, and interaction; how it intersects with other professions, such as journalism, marketing, education, government, business, the law; how history relates to state policy; the role of digital technologies in the public uses of history; and even the very history of public history itself.

In the first half of the semester, students read about public history itself in order to discuss and analyze the field. In the second half of the semester, we turn to a case study by exploring public history approaches to the story of Fannie Barrier Williams, the first African American woman to graduate from the Brockport Normal School (SUNY Brockport’s precursor). She went on to work as a feminist, anti-racist activist in Progressive Era Chicago. Students will become historical experts on Williams through reading and discussion. Then they will collaborate with students in social work, graphic design, and illustration on two projects: a printable timeline exhibit of Williams’ life and times for use as a “pop-up” exhibit; and a well-developed proposal for a public history project based on one essay written by Fannie Barrier Williams that we will read in class (proposals can take many forms, including exhibitions, performances, collaborations, teaching units, websites, your imagination is the limit; they will be posted on the Fannie Barrier Williams Project website).

Things you are expected to do this termDo the readingsArticles and essays on BrightspaceSelected Fannie Barrier Williams essays in The New Woman of Color: The Collected Writings of Fannie Barrier Williams, 1893–1918, ed. Mary Jo Deegan (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2002)Come to class prepared and ready to participate with a constructive spiritComplete assignments, with special focus on our case study collaborative and proposal projectsLearn the basics of digital project management tools ranging: Zoom, Teams, Google Suite (Docs, Sheets, etc.), Slideshow software (Powerpoint, etc.), Slack, Doodle Polls, WordPress, Omeka, etc.Collaborate with other students in different programs as practice for public history’s cross-professional workCite evidence and sources effectively using Chicago Manual of StyleDevelop your own historical expertise and capacity to work on historical topics with diverse partners in diverse settingsRequired BooksFannie Barrier Williams, The New Woman of Color: The Collected Writings of Fannie Barrier Williams, 1893–1918, ed. Mary Jo Deegan (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2002)Available at Brockport BookstoreRecommended: Wanda A. Hendricks, Fannie Barrier Williams: Crossing the Borders of Region and Race (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2013)Additional documentsPDFs or hyperlinks on BrightspaceScheduleThe instructor may adjust the schedule as needed during the term, but he will give clear instructions about any changes.

Week 01 — Putting the History in Public History

Meetings:

M 08/28 Introduction: What Is Public History, Anyway?Read for today:Cherston Lyon et al., “Introducing Public History,” Introduction to Public History: Interpreting the Past, Engaging Audiences (NY: Roman & Littlefield, 2017), 1-14W 08/30 The History of Public HistoryRead for today:Robert Kelley, “Public History: Its Origins, Nature, and Prospects,” The Public Historian 1, 1 (Autumn, 1978), 16-28Denise D. Meringolo, “A New Kind of Technician: In Search of the Culture of Public History,” in Museums, Monuments, and National Parks: Toward a New Genealogy of Public History (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011), xiii-xxxivHST 512: Malgorzata J. Rymsza-Pawlowska, “Hippies Living History,” The Public Historian 41, 4 (November 2019), 36-55Week 02 — Putting the Public in Public History

Meetings:

M 09/04 Labor Day, NO CLASS MEETINGW 09/06 Public History For Whom, By Whom?Read for today:Benjamin Filene, “Passionate Histories: ‘Outsider’ History-Makers and What They Teach Us,” The Public Historian 34, 1 (2012): 11–33Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, “The Presence of the Past: Patterns of Popular Historymaking,” in The Presence of the Past (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2000), 15-36Cathy Stanton, “Hardball History: On the Edge of Politics, Advocacy, and Activism,” History@Work: A Public History Commons, National Council on Public History, 25 March 2015HST 512: Elizabeth Belanger, “Radical Futures: Teaching Public History as Social Justice,” in Radical Roots: Public History and a Tradition of Social Justice Activism, ed. Denise D. Meringolo (Amherst: Amherst College Press, 2021), 295-324Week 03 — Museums, Monuments, Memory, and the Contested Meanings of Public History

DUE M 09/11 ASSIGNMENT 01: Student info 5%

Meetings:

M 09/11 Case Study: The Battle over the Enola Gay—Commemoration vs. HistoryRead for today:Paul Boyer, “Whose History Is It Anyway? Memory, Politics, and Historical Scholarship,” in History Wars: The Enola Gay and Other Battles for the American Past, eds. Edward Linenthal and Tom Engelhardt (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1996), 115-139HST 512: Edward Linenthal, “Anatomy of a Controversy,” in History Wars: The Enola Gay and Other Battles for the American Past, eds. Edward Linenthal and Tom Engelhardt (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1996), 9-62W 09/13 Case Study: Confederate MonumentsRead for today:Kathryn Lafrenz Samuels, “Deliberate Heritage: Difference and Disagreement After Charlottesville.” The Public Historian 41, 1 (February 1, 2019): 121–32Brian Murphy and Katie Owens-Murphy, “Public History in the Age of Insurrection Confronting White Rage in Red States,” The Public Historian 44, 3 (August 2022): 139–63Pick a piece from “Historians on the Confederate Monument Debate,” read and share with classHST 512: Dell Upton, “Why Do Contemporary Monuments Talk So Much?,” in Commemoration in America: Essays on Monuments, Memorialization, and Memory, eds. David Gobel and Daves Rossell (University of Virginia Press, 2013), 11-31HST 512: Sanford Levinson, “Afterword,” Written in Stone: Public Monuments in Changing Societies (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998/2018), 125-195HST 512: Evan Faulkenbury, “‘A Problem of Visibility’: Remembering and Forgetting the Civil War in Cortland, New York,” The Public Historian 41, 4 (November 2019): 83–99Week 04 — Museums, Monuments, Memory, and the Contested Meanings of Public History

Meetings:

M 09/18 Museums, Historical Houses, and Other Sites of Memory and HistoryRead for today:Mike Wallace, “Visiting the Past: History Museums in the United States,” Mickey Mouse History and Other Essays on American Memory (Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press, 1996), 4-27Bonnie Hurd Smith, “Women’s Voices: Reinterpreting Historic House Museums,” in Her Past Around Us: Interpreting Sites for Women’s History (Malabar, Fla: Krieger Pub Co, 2003), 87-101Harriet Senie, “Commemorating 9/11: From the Tribute in Light to Reflecting Absence,” Memorials to Shattered Myths: Vietnam to 9/11 (NY: Oxford University Press, 2016), 122-168HST 512: Steven D. Lubar, “Introduction: Explore,” Inside the Lost Museum: Curating, Past and Present (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), 1-10W 09/20 Museums, Historical Houses, and Other Sites of MemoryRead for today:Lara Kelland, “Unintentional Public Historians: Collective Memory and Identity Production in the American Indian and LGBTQ Liberation Movements,” in Radical Roots, 503-523Jay Anderson, “Living History: Simulating Everyday Life in Living Museums,” American Quarterly 34, 3 (1982): 290-306HST 512: Patricia West, “‘The Bricks of Compromise Settle into Place’: Booker T. Washington’s Birthplace and the Civil Rights Movement,” Domesticating History: The Political Origins of America’s House Museums (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999), 129-157Week 05 — Digital Public History and Fannie Barrier Williams Project

Meetings:

M 09/25 Enter Digital Public HistoryRead for today:Rebecca S. Wingo, Jason A. Heppler, and Paul Schadewald, “Introduction,” in Digital Community Engagement: Partnering Communities with the Academy, eds. Rebecca S. Wingo, Jason A. Heppler, and Paul Schadewald (Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati Press, 2020)Pick one essay from Digital Community Engagement: Partnering Communities with the Academy, eds. Rebecca S. Wingo, Jason A. Heppler, and Paul Schadewald (Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati Press, 2020) to read and share with classAndrew Hurley, “Chasing the Frontiers of Digital Technology: Public History Meets the Digital Divide,” The Public Historian 38, 1 (February 2016): 69–88 Freedom’s Ring: King’s “I Have a Dream” Speech website (The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University in collaboration with Beacon Press’s King Legacy Series)HST 512: David Hochfelder, “Meeting Our Audiences Where They Are in the Digital Age,” National Council on Public History (blog), 30 March 2016HST 512: Lara Kelland, “Digital Community Engagement across the Divides,” National Council on Public History (blog), 20 April 2016W 09/27 Fannie Barrier Williams ProjectRead for today:Mary Jo Deegan, “Fannie Barrier Williams and Her Life as a New Woamn of Color in Chicago, 1893-1918,” in The New Woman of Color: The Collected Writings of Fannie Barrier Williams, 1893–1918, ed. Mary Jo Deegan (DeKalb, Ill: Northern Illinois University Press, 2002),xii-lxWanda Hendricks, “Introduction,” “North of Slavery: Brockport,” and “Completely Surrounded By Screens,” in Fannie Barrier Williams: Crossing the Borders of Region and Race (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 1-49HST 512: Pero Gaglo Dagbovie, “Reflections on Black Public History Past, Present, Future,” in Radical Roots, 525-540Week 06 — Fannie Barrier Williams Project: Developing Expertise

Meetings:

M 10/02 Fannie Barrier WilliamsRead for today:FBW, “A Northern Negros Autobiography,” “The Intellectual Progress of Colored Women of the United States since the Emancipation Proclamation,” “Club Movement among Negro Women,” “Do We Need Another Name?” in The New Woman of Color, 5-46, 84-86W 10/04 Fannie Barrier WilliamsRead for today:FBW, “The Problem of Employment for Negro Women,” “The Colored Girl,” “Colored Women of Chicago,” “Industrial Education—Will It Solve the Negro Problem?,” in The New Woman of Color, 52-57, 63-69, 78-83Week 07 — Fannie Barrier Williams Project: Developing Expertise

DUE M 10/09 ASSIGNMENT 02: Public History History@Work Analytic Essay 10%

Meetings:

M 10/09 Fannie Barrier WilliamsRead for today:Fannie Barrier Williams, “The Need of Social Settlement Work for the City Negro,” “The Frederick Douglass Centre: A Question of Social Betterment and Not of Social Equality,” “Social Bonds in the ‘Black Belt’ of Chicago: Negro Organizations and the New Spirit Pervading,” “The Frederick Douglass Center[: The institutional Foundation],” “A New Method of Dealing with the Race Problem,” in The New Woman of Color, 107-132W 10/11 NO CLASS MEETING Continue Fannie Barrier Williams ReadingRead for today:Fannie Barrier Williams, “Refining Influence of Art,” “An Extension of the Conference Spirit,” “In Memory of Philip D. Armour,” “Eulogy of Susan B. Anthony,” 100-106, 92-95, 135-137DUE F 10/13 Attendance and Participation (Midterm) = 10%

Week 08 — Fannie Barrier Williams: Developing Expertise

Meetings:

M 10/16 NO CLASS MEETING — Fall BreakW 10/18 NO CLASS MEETING FBW Proposal Development Research Time — Visit Drake Memorial Library this week to discuss what secondary scholarly sources you want to identify and read in relation to your idea for your FBW Project Proposal. These sources might be topical about FBW and her historical context or they might be about an area of public history that you want to use for the project (museum display, digital website, etc.).Week 09 — Fannie Barrier Williams Proposal Workshops

DUE M 10/23 ASSIGNMENT 03: FBW Essay Close Reading Analysis and Project Proposal Question/Abstract 20%

Meetings:

M 10/23 FBW Proposal WorkshopW 10/25 FBW Proposal WorkshopWeek 10 — Fannie Barrier Williams: Developing More Expertise

Meetings:

M 10/30 OpenRead for today:secondary readings TBAW 11/01 OpenRead for today:secondary readings TBAWeek 11 — Fannie Barrier Williams Timeline Projects

Meetings:

M 11/06 Timeline Project DevelopmentRead for today:Steven D. Lubar, “Timelines in Exhibitions,” Curator: The Museum Journal 56, 2 (2013): 169–88TBAW 11/08 Timeline Project DevelopmentRead for today:TBAWeek 12 — Fannie Barrier Williams Timeline Projects

DUE M 11/13 ASSIGNMENT 04: FBW Project Proposal Draft 20%

Meetings:

M 11/13 Timeline Project DevelopmentRead for today:TBAW 11/15 Timeline Project DevelopmentRead for today:TBAWeek 13 — Thanksgiving Break

NO MEETINGS:

M 11/20, W 11/22, F 11/24 Thanksgiving break, NO CLASS MEETINGWeek 14 — Fannie Barrier Williams Timeline/Proposal Presentations

Meetings:

M 11/27 FBW PresentationsW 11/29 FBW PresentationsWeek 15 — Conclusions and Reflections

Meetings:

M 12/04 Public History RevisitedRead for today:Cherston Lyon et al., “Introducing Public History,” Introduction to Public History: Interpreting the Past, Engaging Audiences (NY: Roman & Littlefield, 2017), 1-14W 12/06 Reflections and ConclusionsRead for today:TBADUE F 12/08 Attendance and Participation (Since Midterm) = 10%

Final

DUE M 12/18 ASSIGNMENT 05: Final Project Proposal Written and Digital Materials. 25%

Assignments OverviewDUE M 09/11 ASSIGNMENT 01: Student info 5%DUE M 10/09 ASSIGNMENT 02: Public History History@Work Analytic Essay 10%DUE M 10/23 ASSIGNMENT 03: FBW Essay Close Reading Analysis and Project Proposal Question/Abstract 20%DUE M 11/13 ASSIGNMENT 04: FBW Project Proposal Draft 20%DUE M 12/18 ASSIGNMENT 05: Final Project Proposal Written and Digital Materials. 25%DUE F 10/13 Attendance and Participation (Midterm) = 10% DUE F 12/08 Attendance and Participation (Since Midterm) = 10%EvaluationThis course uses a simple evaluation process to help you improve your understanding of public history. Note that evaluations are never a judgment of you as a person; rather, they are meant to help you assess how you are processing material in the course and keep improving your skills of public history knowledge and understanding.

There are four evaluations given for assignments—(1) Yeah; (2) OK; (3) Needs Work; (4) Nah—plus comments, when relevant, based on the rubric below. Remember to honor the Academic Honesty Policy at SUNY Brockport, including no plagiarism. In this course there is no need to use sources outside of the required ones for the class. The instructor recommends not using AI software for your assignments, but rather working on your own writing skills. If you do use AI, you must cite it as you would any other secondary source that is not your own.

Overall course rubricYeah = A-level work. These show evidence of:

clear, compelling assignments that includea credible argument with some originalityargument supported by relevant, accurate and complete evidenceintegration of argument and evidence in an insightful analysisexcellent organization: introduction, coherent paragraphs, smooth transitions, conclusionsophisticated prose free of spelling and grammatical errorscorrect page formatting when relevantaccurate formatting of footnotes and bibliography with required citation and documentationon-time submission of assignmentsfor class meetings, regular attendance and timely preparationoverall, insightful, constructive, respectful and regular participation in class discussionsoverall, a thorough understanding of required course materialOK = B-level work, It is good, but with minor problems in one or more areas that need improvement.

Needs work = C-level work is acceptable, but with major problems in several areas or a major problem in one area.

Nah = D-level work. It shows major problems in multiple areas, including missing or late assignments, missed class meetings, and other shortcomings.

E-level work is unacceptable. It fails to meet basic course requirements and/or standards of academic integrity/honesty.

Assignments rubricSuccessful assignments demonstrate:

Argument – presence of an articulated, precise, compelling argument in response to assignment prompt; makes an evidence-based claim and expresses the significance of that claim; places argument in framework of existing interpretations and shows distinctive, nuanced perspective of argumentEvidence – presence of specific evidence from primary sources to support the argumentArgumentation – presence of convincing, compelling connections between evidence and argument; effective explanation of the evidence that links specific details to larger argument and its sub-arguments with logic and precisionContextualization – presence of contextualization, which is to say an accurate portrayal of historical contexts in which evidence appeared and argument is being madeCitation – wields Chicago Manual of Style citation standards effectively to document use of primary and secondary sourcesStyle – presence of logical flow of reasoning and grace of prose, including:a. an effective introduction that hooks the reader with originality and states the argument of the assignment and its significance

b. clear topic sentences that provide sub-arguments and their significance in relation to the overall argument

c. effective transitions between paragraphs

d. a compelling conclusion that restates argument and adds a final point

e. accurate phrasing and word choice

f. use of active rather than passive voice sentence constructionsCitation: Using Chicago Manual of StyleThere is a nice, quick overview of citation from the Chicago Manual of Style Shop Talk website. It includes lots of information, including:

a. Formatting endnotes

b. Tipsheet (PDF)For additional, helpful guidelines, visit the Drake Memorial Library’s Chicago Manual of Style pageYou can always go right to the source: the 17th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style is available for reference at the Drake Memorial Library Reserve DeskWriting consultation

Writing Tutoring is available through the Academic Success Center. It will help at any stage of writing. Be sure to show your tutor the assignment prompt and syllabus guidelines to help them help you.

Research consultationThe librarians at Drake Memorial Library are an incredible resource. You can consult with them remotely or in person. To schedule a meeting, go to the front desk at Drake Library or visit the library website’s Consultation page.

Attendance PolicyYou will certainly do better with evaluation in the course, learn more, and get more out of the class the more you attend meetings, participate in discussions, complete readings, and finish assignments. That said, lives get complicated. Therefore, you may miss up to four class meetings, with or without a justified reason (this includes sports team travel, illness, or other reasons). If you are ill, please stay home and take precautions if you have any covid or flu symptoms. Moreover, masks are welcome in class if you are still recovering from illness or feel sick. You do not need to notify the instructor of your absences. After five absences, subsequent absences will result in reduction of final grade at the discretion of the instructor. Generally, more than four absences results in the loss of one letter grade from final evaluation.

Disabilities and accommodationsIn accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and Brockport Faculty Senate legislation, students with documented disabilities may be entitled to specific accommodations. SUNY Brockport is committed to fostering an optimal learning environment by applying current principles and practices of equity, diversity, and inclusion. If you are a student with a disability and want to utilize academic accommodations, you must register with Student Accessibility Services (SAS) to obtain an official accommodation letter which must be submitted to faculty for accommodation implementation. If you think you have a disability, you may want to meet with SAS to learn about related resources. You can find out more about Student Accessibility Services at their website or by contacting SAS via the email address sasoffice@brockport.edu or phone number (585) 395-5409. Students, faculty, staff, and SAS work together to create an inclusive learning environment. Feel free to contact the instructor with any questions.

Discrimination and harassment policiesSex and Gender discrimination, including sexual harassment, are prohibited in educational programs and activities, including classes. Title IX legislation and College policy require the College to provide sex and gender equity in all areas of campus life. If you or someone you know has experienced sex or gender discrimination (including gender identity or non-conformity), discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or pregnancy, sexual harassment, sexual assault, intimate partner violence, or stalking, we encourage you to seek assistance and to report the incident through these resources. Confidential assistance is available on campus at Hazen Center for Integrated Care. Another resource is RESTORE. Note that by law faculty are mandatory reporters and cannot maintain confidentiality under Title IX; they will need to share information with the Title IX & College Compliance Officer.

Statement of equity and open communicationWe recognize that each class we teach is composed of diverse populations and are aware of and attentive to inequities of experience based on social identities including but not limited to race, class, assigned gender, gender identity, sexuality, geographical background, language background, religion, disability, age, and nationality. This classroom operates on a model of equity and partnership, in which we expect and appreciate diverse perspectives and ideas and encourage spirited but respectful debate and dialogue. If anyone is experiencing exclusion, intentional or unintentional aggression, silencing, or any other form of oppression, please communicate with me and we will work with each other and with SUNY Brockport resources to address these serious problems.

Disruptive student behaviorsPlease see SUNY Brockport’s procedures for dealing with students who are disruptive in class.

Emergency alert systemIn case of emergency, the Emergency Alert System at The College at Brockport will be activated. Students are encouraged to maintain updated contact information using the link on the College’s Emergency Information website.

History Department learning goalsThe study of history is essential. By exploring how our world came to be, the study of history fosters the critical knowledge, breadth of perspective, intellectual growth, and communication and problem-solving skills that will help you lead purposeful lives, exercise responsible citizenship, and achieve career success. History Department learning goals include:

Articulate a thesis (a response to a historical problem)Advance in logical sequence principal arguments in defense of a historical thesisProvide relevant evidence drawn from the evaluation of primary and/or secondary sources that supports the primary arguments in defense of a historical thesisEvaluate the significance of a historical thesis by relating it to a broader field of historical knowledgeExpress themselves clearly in writing that forwards a historical analysis.Use disciplinary standards (Chicago Manual of Style) of documentation and citation when referencing historical sourcesIdentify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they appear in their own and others’ workWrite and reflect on the writing conventions of the disciplinary area, with multiple opportunities for feedback and revision or multiple opportunities for feedbackDemonstrate understanding of the methods historians use to explore social phenomena, including observation, hypothesis development, measurement and data collection, experimentation, evaluation of evidence, and employment of interpretive analysisDemonstrate knowledge of major concepts, models and issues of historyDevelop proficiency in oral discourse and evaluate an oral presentation according to established criteriaSyllabus—Modern America

What are we up to?

What are we up to?How did we get here? This is the core question at stake in historical study. Figuring out answers to that question, however, demands more than simply developing a personal opinion. It means wielding evidence to make compelling interpretations in dialogue with what other historians have to say. Modern America allows you to gain better knowledge of one place over the course of one period of time: the United States of America since the Civil War ended in 1865 to the present. As we study the United States since the Civil War, the course also helps you expand your skills of empirical analysis, debate and dialogue, listening and responding thoughtfully to others, writing and communication, and understanding at least some of the complex dynamics of human interaction. Interactive lectures, primary and secondary source readings, in-class discussion and debate, and critical analysis assignments allow you to explore how a wide range of Americans shaped systems of power, patterns of resistance, socio-political identities, and cultural and intellectual life. To be sure, your goal is to acquire what every citizen of the world needs: a basic outline of what happened when and by whom; but you will also hone skills beyond merely history as the memorization of dates, names, and facts. These include improving your abilities to frame effective historical questions of inquiry, assess and interpret arguments about the past, evaluate and compare evidence for persuasiveness, research and write effectively, and use the Chicago Manual of Style for citation.

Things you are expected to do this termDo the readings and wield sources to study the past“Primary sources” are the selected historical documents in Foner’s Voices of Freedom, Volume II, Seventh Edition and additional materials provided by instructorThe “secondary source” in this class is Eric Foner’s book, Give Me Liberty! Volume II, Brief Seventh Edition and any additional interpretive readings about the pastWatch the interactive lectures on Voicethread, complete the response assignmentsCome to class prepared, attendance will affect your gradeParticipate in discussions in classMeet with a research librarian at Drake Memorial LibraryComplete the critical analysis and research assignmentsLearn how to cite evidence and sources effectively using Chicago Manual of StyleShift from “this is my opinion” to “this evidence, compared to other evidence, is (or is not) persuasive”—this is a core aspect of what the discipline of history is aboutRequired BooksEric Foner, Kathleen Duval, and Lisa McGirr, Give Me Liberty! Volume II BRIEF 7th Edition (New York: WW Norton, 2023)Eric Foner, Kathleen Duval, and Lisa McGirr,Voices of Freedom Volume II (New York: WW Norton, 2023)Available at Brockport Bookstore or online in both print and digital formats. *NOTE: Be sure to purchase the correct editions of the books.*Additional documentsPDFs or hyperlinks on BrightspaceScheduleThe instructor may adjust the schedule as needed during the term, but will give clear instructions about any changes.

Week 01 — Reconstruction

Meetings:

M 08/28 A Visit to Edisto, South Carolina (Discussion)W 08/30 Course Overview, Reconstructing History (Voicethread and Class Meeting)F 09/02 Reconstruction (Voicethread and Class Meeting)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Preface, xxiv-xxxviiGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 15, What Is Freedom?: Reconstruction, 1865-1877,” 441-474Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 28, A Divided Nation, 887-933Voices of Freedom, Ch. 15, 1-27Martin Pengelly, “A disputed election, a constitutional crisis, polarisation…welcome to 1876” (interview with Eric Foner), The Guardian, 23 August 2020Optional: Kevin M. Levin, “How Slavery Almost Didn’t End in 1865,” Civil War Memory, 6 December 2022Optional: 1865 Podcast (historical fictional)Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: John Daly, “The Southern Civil War 1865-1877: When Did the Civil War End?,” on BrightspaceWeek 02 — Industrialization

Meetings:

M 09/04 Labor Day, NO CLASS MEETINGW 09/06 The “Hog Squeal of the Universe” and the “Incorporation” of America (Voicethread and Class Meeting)F 09/08 Who Built America? Class Conflict (Discussion)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 16, America’s Gilded Age, 1870-1890, 475-511Voices of Freedom, Ch. 16, 28-55Joshua Specht, “The price of plenty: how beef changed America,” Guardian, 7 May 2019Week 03 — Expansion

Meetings:

M 09/11 Settler Colonialism to Formal Empire (Voicethread and Class Meeting)W 09/13 Do Native Americans Have Sovereignty? (Discussion)F 09/15 Should America Have Colonies? (Discussion)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 17, Freedom’s Boundaries, at Home and Abroad, 1890-1900, 512-545Voices of Freedom, Ch. 16, 56-77 Hopi Petition Asking for Title to Their Lands (1894), scroll down to read the transcription, especially p. 7Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94 (1884), Syllabus (full case optional if you are interested)Christine DeLucia, Doug Kiel, Katrina Phillips, and Kiara Vigil, “Histories of Indigenous Sovereignty in Action: What is it and Why Does it Matter?,” The American Historian, March 2021Assignment:

DUE M 09/11 ASSIGNMENT 01: Student info = 2%Week 04 — Progressivism

Meetings:

M 09/18 Did the Progressive Era Make Progress? (Voicethread and Class Meeting)W 09/20 Jim Crow: The Nadir (Voicethread and Class Meeting)F 09/22 Plessy v. Ferguson (Discussion)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 18, The Progressive Era, 1900-1916, 546-577Voices of Freedom, Ch. 18, 78-106Various Authors, “Suffrage at 100,” New York Times, 2019-2020Optional: Noam Maggor, “Tax Regimes: An interview with Robin Einhorn,” Phenomenal World, 24 March 2022Optional Brockport Faculty Listening: Elizabeth Garner Masarik, “100 Years of Woman Suffrage,” Dig! A History Podcast, 5 January 2020Assignment:

DUE M 09/18 ASSIGNMENT 02: Reconstruction = 10%Week 05 — WWI and Its Aftermath

Meetings:

M 09/25 War As Progress? (Interactive Lecture)W 09/27 Making the Postwar World Safe for Democracy? (Interactive Lecture)F 09/29 National Unity vs. Civil Liberties (Discussion)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 19, Safe for Democracy: The United States and World War I, 1916-1920, 578-611Voices of Freedom, Ch. 19, 107-135Week 06 — The Roaring Twenties

Meetings:

M 10/02 Roars of Modernity (Voicethread and Class Meeting)W 10/04 Roars of Antimodernity (Voicethread and Class Meeting)F 10/06 Write a Hit Song About the Twenties (Discussion)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 20, From Business Culture to Great Depression in the “Roaring” Twenties, 1920-1932, 612-642Voices of Freedom, Ch. 20, 136-163Assignment:

DUE M 10/02 ASSIGNMENT 03: Industrialization and Expansion = 10%Week 07 — The New Deal

Meetings:

M 10/09 What Caused the Great Depression? (Voicethread and Class Meeting)W 10/11 Watch Online: FDR’s New Deal and the Making of “Modern” Liberalism — Introduction to Drake Memorial Library Resources and Preparation for Final Assignment (Voicethread and Class Meeting)F 10/13 NO CLASS MEETING — Watch Online: Planting a Flag at Iwo Jima (Voicethread)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 21: The New Deal, 1932-1940, 643- 675Voices of Freedom, Ch. 21, 164-190Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Anne S. Macpherson, “Birth of the U.S. Colonial Minimum Wage: The Struggle over the Fair Labor Standards Act in Puerto Rico, 1938– 1941,” Journal of American History 104, 3 (December 2017), 656-680, on BrightspaceWeek 08 — WWII

Meetings:

M 10/16 NO CLASS MEETING — Fall BreakW 10/18 Watch Online: Was World War II the Actual New Deal? — Introduction to Drake Memorial Library Resources and Preparation for Final Assignment (Voicethread and Class Meeting)F 10/20 The Rise of Modern Liberalism During the Great Depression and World War II (Discussion)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 22, Fighting for the Four Freedoms: World War II, 1941-1945, 676-711Voices of Freedom, Ch. 22, 191-212Assignment:

DUE M 10/16 ASSIGNMENT 04: Progressivism = 10%Week 09 — Cold War

Meetings:

M 10/23 Debating “Modern” Liberalism: The American Century or Century of the Common Man? (Discussion)W 10/25 Cold War Containments (Voicethread and Class Meeting)F 10/27 Cold War Rebellions (Voicethread and Class Meeting)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 23, The United States and the Cold War, 1945-1953, 712-740Voices of Freedom, Ch. 23, 213-245Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Bruce Leslie (and John Halsey), “A College Upon a Hill: Exceptionalism & American Higher Education,” in Marks of Distinction: American Exceptionalism Revisited, ed. Dale Carter (Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 2001), 197-228, on BrightspaceWeek 10 — The Modern African American Civil Rights Movement

Meetings:

M 10/30 Reconstruction Redux? The Modern African American Civil Rights Movement (Voicethread and Class Meeting)W 11/01 The Two Versions of John Lewis’s 1962 March on Washington Speech (Discussion)F 11/03 Beyond the “Martin vs. Malcolm” Binary (Discussion)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 24, An Affluent Society, 1953-1960, 741-772Voices of Freedom, Ch. 24, 246-269Keisha N. Blain, “Fannie Lou Hamer’s Dauntless Fight for Black Americans’ Right to Vote,” Smithsonian Magazine, 20 August 2020Freedom’s Ring: King’s “I Have a Dream” Speech website (The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University in collaboration with Beacon Press’s King Legacy Series)Lauren Feeney, “Two Versions of John Lewis’ Speech,” Moyers and Company, 24 July 2013Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Meredith Roman, “The Black Panther Party and the Struggle for Human Rights,” Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men 5, 1, The Black Panther Party (Fall 2016), 7-32Assignment:

DUE M 10/30 ASSIGNMENT 05: Midterm essay. Roaring Twenties to World War II document comparison and analysis = 15%Week 11 — The Sixties

Meetings:

M 11/06 A Great Society? A New Frontier, a New Left, a New Right (Voicethread and Class Meeting)W 11/08 Vietnam: The Quagmire (Voicethread and Class Meeting)F 11/10 Should the US Withdraw from Vietnam? (Discussion)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 25, The Sixties, 1960-1968, 773-807Voices of Freedom, Ch. 25, 270-305Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Michael J. Kramer, “The Woodstock Transnational: Rock Music & Global Countercultural Citizenship After the Vietnam War,” The Republic of Rock Book Blog, 22 October 2018Week 12 — The Seventies and Eighties

Meetings:

M 11/13 Disco Demolition: The Loss of Trust from Watergate to the Malaise Speech (Voicethread and Class Meeting)W 11/15 Was the Volcker Shock the Right Move? (Discussion)F 11/17 Revolting Conservatives: The Reagan Revolution and the Rise of the New Right (Voicethread and Class Meeting)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 26, The Conservative Turn, 1969-1988, 808-845Voices of Freedom, Ch. 26, 306-331Tim Barker, “Other People’s Blood,” N 1, 34, Spring 2019Moira Donegan, “How to Survive a Movement: Sarah Schulman’s monumental history of ACT UP,” Bookforum, 1 June 2021Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: James Spiller, “Nostalgia for the Right Stuff: Astronauts and Public Anxiety about a Changing Nation,” in Michael Neufeld ed., Spacefarers: Images of Astronauts and Cosmonauts in the Heroic Era of Spaceflight (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Scholarly Press, 2013), 57-76, on BrightspaceWeek 13 — Thanksgiving Break

NO MEETINGS:

M 11/20, W 11/22, F 11/24 Thanksgiving break, NO CLASS MEETINGReadings:

Optional: Lawrence B. Glickman, “The Fruits of Their Labors: How Thanksgiving became a free-enterprise holiday,” Slate, 22 November 2021Assignment:

DUE M 11/20 ASSIGNMENT 06: Cold War Final Book Review Essay Research Librarian Visit = 8%Week 14 — Uncertain Times: The Nineties

Meetings:

M 11/27 The Uncertainty of the 1990s (Voicethread and Class Meeting)W 11/29 Debating the Personal Responsibility Act of 1996 and Welfare Reform (Discussion)F 12/01 OpenReadings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 27, A New World Order, 1989-2004, 846-886Voices of Freedom, Ch. 27, 332-345Week 15 — Is American Modern Yet?

Meetings:

M 12/04 Challenges of a New Century: The 2000 Election, 9/11, the War on Terror, and the Great Recession of 2008 (Voicethread and Class Meeting)W 12/06 Making America Great Again? The Obama and Trump Eras (Voicethread and Class Meeting)F 12/08 Is America Modern Yet? Closing Discussion (Discussion)Readings due this week:

Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 28, A Divided Nation, 887-933Voices of Freedom, Ch. 28Adam Serwer, “The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts,” The Atlantic, 23 December 2019, on BrightspaceAssignment:

DUE M 12/04 ASSIGNMENT 07: Cold War Final Book Review Essay Proposal = 10%DUE M 12/11 ASSIGNMENT 08: US Since 1989 = 10%Final

Assignment: DUE M 12/18 ASSIGNMENT 09: Final essay. Cold War Book Review Essay = 15%

Assignments OverviewDUE M 09/11 ASSIGNMENT 01: Student info = 2%DUE M 09/18 ASSIGNMENT 02: Reconstruction = 10%DUE M 10/02 ASSIGNMENT 03: Industrialization and Expansion = 10%DUE M 10/16 ASSIGNMENT 04: Progressivism = 10%DUE M 10/30 ASSIGNMENT 05: Midterm essay. Roaring Twenties to World War II document comparison and analysis = 15%DUE M 11/20 ASSIGNMENT 06: Cold War Final Book Review Essay Research Librarian Visit = 8%DUE M 12/04 ASSIGNMENT 07: Cold War Final Book Review Essay Proposal = 10%DUE M 12/11 ASSIGNMENT 08: US Since 1989 = 10%DUE M 12/18 ASSIGNMENT 09: Final essay. Cold War Book Review Essay = 15%DUE F 10/13 Attendance and Participation (Midterm) = 5%DUE F 12/08 Attendance and Participation (Since Midterm) = 5%EvaluationThis course uses a simple evaluation process to help you improve your understanding of both US history since the Civil War and history as a method. Note that evaluations are never a judgment of you as a person; rather, they are meant to help you assess how you are processing material in the course and how you can keep improving college-level and lifelong skills of historical knowledge and skills. Remember that history is a craft and it takes practice and iteration to improve, as with any knowledge and skill you wish to develop; but, if you keep at it, thinking historically can help you understand the complexities of the world more powerfully.

There are four evaluations given for assignments—(1) Yeah; (2) OK; (3) Needs Work; (4) Nah—plus comments, when relevant, based on the rubric below. Remember to honor the Academic Honesty Policy at SUNY Brockport, including no plagiarism. In this course there is no need to use sources outside of the required ones for the class. The instructor recommends not using AI software for your assignments, but rather working on your own writing skills. If you do use AI, you must cite it as you would any other secondary source that is not your own.

Overall course rubricYeah = A-level work. These show evidence of:

clear, compelling assignments that includea credible argument with some originalityargument supported by relevant, accurate and complete evidenceintegration of argument and evidence in an insightful analysisexcellent organization: introduction, coherent paragraphs, smooth transitions, conclusionsophisticated prose free of spelling and grammatical errorscorrect page formatting when relevantaccurate formatting of footnotes and bibliography with required citation and documentationon-time submission of assignmentsfor class meetings, regular attendance and timely preparationoverall, insightful, constructive, respectful and regular participation in class discussionsoverall, a thorough understanding of required course materialOK = B-level work, It is good, but with minor problems in one or more areas that need improvement.

Needs work = C-level work is acceptable, but with major problems in several areas or a major problem in one area.

Nah = D-level work. It shows major problems in multiple areas, including missing or late assignments, missed class meetings, and other shortcomings.

E-level work is unacceptable. It fails to meet basic course requirements and/or standards of academic integrity/honesty.

Assignments rubricSuccessful assignments demonstrate:

Argument – presence of an articulated, precise, compelling argument in response to assignment prompt; makes an evidence-based claim and expresses the significance of that claim; places argument in framework of existing interpretations and shows distinctive, nuanced perspective of argumentEvidence – presence of specific evidence from primary sources to support the argumentArgumentation – presence of convincing, compelling connections between evidence and argument; effective explanation of the evidence that links specific details to larger argument and its sub-arguments with logic and precisionContextualization – presence of contextualization, which is to say an accurate portrayal of historical contexts in which evidence appeared and argument is being madeCitation – wields Chicago Manual of Style citation standards effectively to document use of primary and secondary sourcesStyle – presence of logical flow of reasoning and grace of prose, including:a. an effective introduction that hooks the reader with originality and states the argument of the assignment and its significance

b. clear topic sentences that provide sub-arguments and their significance in relation to the overall argument

c. effective transitions between paragraphs

d. a compelling conclusion that restates argument and adds a final point

e. accurate phrasing and word choice

f. use of active rather than passive voice sentence constructionsCitation: Using Chicago Manual of StyleThere is a nice, quick overview of citation from the Chicago Manual of Style Shop Talk website. It includes lots of information, including:

a. Formatting endnotes

b. Tipsheet (PDF)For additional, helpful guidelines, visit the Drake Memorial Library’s Chicago Manual of Style pageYou can always go right to the source: the 17th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style is available for reference at the Drake Memorial Library Reserve DeskWriting consultation

Writing Tutoring is available through the Academic Success Center. It will help at any stage of writing. Be sure to show your tutor the assignment prompt and syllabus guidelines to help them help you.

Research consultationThe librarians at Drake Memorial Library are an incredible resource. You can consult with them remotely or in person. To schedule a meeting, go to the front desk at Drake Library or visit the library website’s Consultation page.

Attendance PolicyYou will certainly do better with evaluation in the course, learn more, and get more out of the class the more you attend meetings, participate in discussions, complete readings, and finish assignments. That said, lives get complicated. Therefore, you may miss up to four class meetings, with or without a justified reason (this includes sports team travel, illness, or other reasons). If you are ill, please stay home and take precautions if you have any covid or flu symptoms. Moreover, masks are welcome in class if you are still recovering from illness or feel sick. You do not need to notify the instructor of your absences. After five absences, subsequent absences will result in reduction of final grade at the discretion of the instructor. Generally, more than four absences results in the loss of one letter grade from final evaluation.

Disabilities and accommodationsIn accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and Brockport Faculty Senate legislation, students with documented disabilities may be entitled to specific accommodations. SUNY Brockport is committed to fostering an optimal learning environment by applying current principles and practices of equity, diversity, and inclusion. If you are a student with a disability and want to utilize academic accommodations, you must register with Student Accessibility Services (SAS) to obtain an official accommodation letter which must be submitted to faculty for accommodation implementation. If you think you have a disability, you may want to meet with SAS to learn about related resources. You can find out more about Student Accessibility Services at their website or by contacting SAS via the email address sasoffice@brockport.edu or phone number (585) 395-5409. Students, faculty, staff, and SAS work together to create an inclusive learning environment. Feel free to contact the instructor with any questions.

Discrimination and harassment policiesSex and Gender discrimination, including sexual harassment, are prohibited in educational programs and activities, including classes. Title IX legislation and College policy require the College to provide sex and gender equity in all areas of campus life. If you or someone you know has experienced sex or gender discrimination (including gender identity or non-conformity), discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or pregnancy, sexual harassment, sexual assault, intimate partner violence, or stalking, we encourage you to seek assistance and to report the incident through these resources. Confidential assistance is available on campus at Hazen Center for Integrated Care. Another resource is RESTORE. Note that by law faculty are mandatory reporters and cannot maintain confidentiality under Title IX; they will need to share information with the Title IX & College Compliance Officer.

Statement of equity and open communicationWe recognize that each class we teach is composed of diverse populations and are aware of and attentive to inequities of experience based on social identities including but not limited to race, class, assigned gender, gender identity, sexuality, geographical background, language background, religion, disability, age, and nationality. This classroom operates on a model of equity and partnership, in which we expect and appreciate diverse perspectives and ideas and encourage spirited but respectful debate and dialogue. If anyone is experiencing exclusion, intentional or unintentional aggression, silencing, or any other form of oppression, please communicate with me and we will work with each other and with SUNY Brockport resources to address these serious problems.

Disruptive student behaviorsPlease see SUNY Brockport’s procedures for dealing with students who are disruptive in class.

Emergency alert systemIn case of emergency, the Emergency Alert System at The College at Brockport will be activated. Students are encouraged to maintain updated contact information using the link on the College’s Emergency Information website.

History Department learning goalsThe study of history is essential. By exploring how our world came to be, the study of history fosters the critical knowledge, breadth of perspective, intellectual growth, and communication and problem-solving skills that will help you lead purposeful lives, exercise responsible citizenship, and achieve career success. History Department learning goals include:

Articulate a thesis (a response to a historical problem)Advance in logical sequence principal arguments in defense of a historical thesisProvide relevant evidence drawn from the evaluation of primary and/or secondary sources that supports the primary arguments in defense of a historical thesisEvaluate the significance of a historical thesis by relating it to a broader field of historical knowledgeExpress themselves clearly in writing that forwards a historical analysis.Use disciplinary standards (Chicago Manual of Style) of documentation and citation when referencing historical sourcesIdentify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they appear in their own and others’ workWrite and reflect on the writing conventions of the disciplinary area, with multiple opportunities for feedback and revision or multiple opportunities for feedbackDemonstrate understanding of the methods historians use to explore social phenomena, including observation, hypothesis development, measurement and data collection, experimentation, evaluation of evidence, and employment of interpretive analysisDemonstrate knowledge of major concepts, models and issues of historyDevelop proficiency in oral discourse and evaluate an oral presentation according to established criteriaJuly 31, 2023

Rovings

Roberto de la Torre, Vellarron de Catrelo de Cima, Galicia.Sounds

The Strangeness of Dub