Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 12

December 31, 2023

The Disorderly Thrust of Politics

The disorderly thrust of political events disturbs the symmetry of political analysis.

— Stuart Hall

December 18, 2023

Raising the Bar

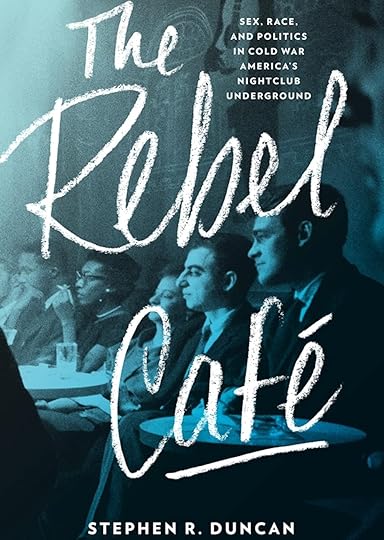

X-posted from the Society for US Intellectual History Book Review.

If you want to get out of America, go to Greenwich Village.

— Bob Dylan, quoting folklorist Alan Lomax[1]

Stephen Duncan’s book about the “nightclub underground” of America during the 1940s and 50s takes us to the caverns and taverns that started in subterranean quarters and eventually changed the culture, politics, and economics of the United States. While many historians have gestured to the significance of this bohemian world, few have done so with such geographic, and almost archeological, precision.[2] Using new archival sources, Duncan helps us peer more clearly into the dimly lit bars, coffeehouses, and cabarets found in neighborhoods such as San Francisco’s North Beach and New York City’s Greenwich Village. There, he notices how venues for hanging out and socializing catalyzed larger social movements and progressive politics in the United States. Even unlikely new forms of mass consumerism arose from these very places whose clientele seemed, at first glance, to be avoiding, or even resisting, mainstream forms of capitalism. In The Rebel Café, Duncan demonstrates how milieus matter, how the seemingly ephemeral turns out to be essential, how culture decisively shapes ideas, and how particular places, even obscure, marginal ones, can incubate surprisingly powerful historical forces.

Overall, Duncan’s innovation is to get us into the details of hazy, half-forgotten atmospheres, but rather than merely romanticize bohemian nightlife as a vague context of rebellion, Duncan shows how casual conversations, interactions, entertainments, performances, and activities wound up gathering unexpected weight and momentum. They ultimately inspired sturdier and more lasting transformations. The watering holes and gathering spots of bohemian Greenwich Village and North Beach, he contends, supported “a diverse coalition of devotees, including artists, performers, and audiences, united in an informal project to redefine the meaning of America, placing an experimental pluralism alongside demands for personal liberty” (2). Theirs was a resolutely cultural project, but to Duncan it had profound political implications. “Tucked away in the underground,” he contends, “politically conscious cultural producers carried forward a species of left-wing activism that repopulated American politics in the 1960s” (3). As Duncan tells the story, collective democracy, individual freedom, and the very reimagining of the American project itself were at stake.

One might say that with The Rebel Café, Stephen Duncan has written an institutional history of a resolutely anti-institutional topic: nightlife.[3] It is a refreshing approach. Too often, contemporary historians mistakenly picture culture as the result of politics. Culture becomes but politics’ more meager outcome. Duncan works against the assumption that politics is the all-encompassing domain in which culture is but a part. He wants his readers to notice how power itself sometimes gets generated in the most unlikely of places. Not that Duncan idealizes the “rebel café,” a term he adapts from the poet Allen Ginsberg. He certainly wants us to notice its fraught, vexing history. He wants us to pay attention to its politics. Nonetheless, his book is keen to show how culture produces politics, not the reverse. Grounded (undergrounded?) in careful archival research, The Rebel Café unearths the seemingly buried remains of a once vibrant cultural upheaval that many think simply vanished into the wee hours of the past. Bringing us into the key locales of a bicoastal network that linked Greenwich Village and North Beach, Duncan shows how they nurtured postwar rebellion. This is a consequential study of nascent activities, a stupendous act of recovery that helps us see better the faint, sketchy glimmers of historical change in postwar life. While he never fully explains why we should not also be looking at Chicago, Los Angeles, or global circuits of nightlife, he convincingly shows how New York City and San Francisco were exemplary spots. Moreover, Duncan offers new metaphors for how we might think about the importance of culture itself no matter where it does its thing. His book raises the bar both on how we can understand postwar America and how we might conceptualize the very methods of cultural history.

In The Rebel Café, Duncan takes us through six chapters that are both chronological and distinctively thematic. The first two provide background on the role of nightspots. They were “places of public discussion” that smuggled the ethos and networks of the 1930s Popular Front, that mix of radicals and liberals focused on expanding the New Deal State and its base of industrial unions, right past the McCarthyism of the 1950s (14) For Duncan, if one looks to the “nocturnal underground,” one glimpses continuities rather than the rupture of the Red Scare that many historians typically note.[4] Painters at the Cedar Tavern, the anarcho-syndicalist poets such as Kenneth Rexroth at the Black Cat in San Francisco, Gay poets such as Robert Duncan and Allen Ginsberg, and women artists ranging from Anaïs Nin to Judith Molina of the Living Theater to Maya Angelou settled into these locales for their restless efforts to forge new paths in artmaking and politics.

This smuggled Popular Front culture was a man’s world, to be sure, but not one without opportunities for proto-feminist activities. “Unconventional women who claimed a public voice within the Rebel Café were part of a broad public discussion in which the media interacted with subterranean bar talk,” Duncan explains, “resulting in a conversation that helped to transform American gender norms” (210). His point is neither that these activities were more important than politics, nor that the social movements that followed in their wake during the 1960s and 70s were any less important. Rather, Duncan wants us to glimpse the “early stirrings” of postwar social transformations (210). Clubs such as San Francisco’s Black Cat also figured in legal struggles for gay liberation. Drawing on the work of Nan Alamilla Boyd, Duncan points out that Black Cat owner Sol Stoumen’s 1951 California Supreme Court case Stoumen v. Reilly, which prevented the removal of liquor licenses based on the sexuality of customers, “cannot be divorced from the café’s bohemian and leftist history” (210).[5] Instead, we must grasp “the absorption of sexuality into a larger liberatory program” (69). While today, identity politics stratifies movements for women’s, gay, Black, and myriad other rights into discrete efforts, Duncan wants us to notice how much they intersected, interacted, and intertwined in the smoky dens of 1950s bohemia.

Chapters three, four, and five concentrate on this bohemian nightlife in its heyday. Duncan examines, respectively, jazz, the Beats, and nightclub comedy. Here issues of race, community, and free speech move to the fore. Duncan contends, convincingly, that the milieu of the Rebel Café contributed to the “integrationist imperative” of “cross-racial exchange” and the “universalist ethos” of jazz. Ultimately, it provided one base for direct participation in the Black liberation struggle (80). This was because while race in the nocturnal underground was anything but utopian, and repeatedly it was shaped by overly romanticized tropes, the milieu of the Rebel Café did see the “the slow transformation and gradual erosion of social hierarchy” (100). Meanwhile, Beat writers led the charge of a bohemian search for community. A café such as the Coexistence Bagel Shop became what one historian has called a “bohemian news center,” and bicoastal, even nascent international networks arose as alternatives to Eisenhower America in the 1950s and the constraints of the Cold War (127).[6] People of all sorts moved through these spaces. Women pursued new modes of authenticity despite the continued misogyny of the Rebel Café (62-63, 146-149, 210-219, 235). Socialists such as Michael Harrington combined an anti-Stalinist democratic socialist politics with long hours drinking and chatting at places such as the White Horse Tavern (150, 205). In the post-New Deal compression of wealth across the spectrum of American society, what the poet Gary Snyder called “proletarian bohemians” arose alongside the more traditional slumming of upper-class hipsters (151).

For Duncan, one began to see this underground culture trespass on mainstream life with the emergence of comics such as Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce, and Dick Gregory. Sahl created a bridge from bohemian clubs to the comedic style of both the collegiate set and the Rat Pack (156-157). Lenny Bruce introduced a new insistence on authenticity, claiming his nightclub act wasn’t an act at all. His arrests and subsequent trials created as much publicity as his startling performances themselves (167-184). Dick Gregory used his success in the nightclubs of the “rebel café” to attain a more widespread success, but at the same time, the African American comic forcefully brought civil rights struggles with him from the underground (184-192). The question, however, of how successful Rebel Café nightlife culture was at pushing forward larger political goals remains unclear. The anarcho-libertarian openness of these spaces, so potent for making them zones of escape for misfits, artists, bohemians, and radicals in postwar America, also, Duncan claims, “nudged out attention to structural inequality and systems of power” (227-228). Even their modes of critique could, as Duncan is quick to notice, divide. Middle-class Americans might feel smugly superior when defending Lenny Bruce’s freedom of speech, and maybe even agreeing with the content of his critiques, but the comic’s harsh, frank rhetoric of rejection and rebellion, hip as it might have been, quickly alienated working-class Americans who were desperate to hang on to the precarious new stability they had secured during the post-New Deal, post-World War II liberal consensus.[7] One could not build a mass political movement from this particular subterranean culture of rebellion, for “its lack of attention to economics left its politics atomized and effective only at the margins.” It could not sustain “significant cross-class alliances” (228). So much, I guess, for Gary Snyder’s “proletarian bohemians” (151).

Neither could the Rebel Café, as constituted in postwar America, conquer dilemmas of gender or race or sexual equality. Nonetheless, Duncan recovers the stories of figures who tried and ways in which underground nightlife marked an essential launching ground for larger changes. Bob Kaufman, for instance, appears as a fantastically sophisticated bohemian activist in San Francisco (142, 200-201). Duncan points to the obvious Rebel Café origins of the Stonewall Riots that sparked the gay liberation movement in the late 1960s (235-236). We learn how the urban reforms of Jane Jacobs had deep connections to the nightclubs and bars of Greenwich Village (206). Duncan even notes how the radical separatist Black activism of Amiri Baraka and the Umbra group used the Rebel Café’s infrastructure to develop programs and campaigns (236). When it comes to the social movements of the 1960s as a whole, Duncan believes that “the relevance of bohemia in the 1950s was its willingness to relinquish at least some privileges of race and class, and to think outside the lines about what the shape of the nation should be” (236). For Duncan, “the bohemians of North Beach and Greenwich VIllage recognized this and attempted, however fumblingly, to devise a new kind of community in response” (236). It is easy to dismiss the botched attempts to be different, but maybe it us just as crucial to notice, as Duncan does, the moments when the underground simmered, imperfectly, with possibilities.

Eventually, however, the mainstream won out. As chapter six of The Rebel Café explains, by the 1960s, “the Rebel Café was no longer underground, but instead became indistinguishable from American culture as a whole” (186). This is a well-known argument about cooptation of cultural rebellion made in one form or another by everyone from Todd Gitlin to Alice Echols to Thomas Frank (just to name a few of its proponents). Frank has most intriguingly contended that it was never anything but part of the so-called “establishment.” Hip nightlife rebellion was as much a movement within the glass window office towers of corporate consumer marketing departments as it was a creature from the depths of the nocturnal underworld.[9] Duncan does not do enough to respond to Frank’s contentions, but his research suggests that while to be sure there were porous, Mad Men-like lines of connection between nightlife culture and new strategies of corporate advertising, there were also noticeable distinctions. This was particularly the case with origins. While Frank wants to emphasize that postwar rebellion was nothing more than a lifestyle creation of Madison Avenue, Duncan wants us to go downtown. In the nightlife underground, he contends, “past programs like the Popular Front” lingered. Eventually they “threaded their way through the culture industry’s large corporations” (197). While Frank wants to root styles of countercultural rebellion solely in the business history of marketing and advertising itself, Duncan insists that we miss the importance of the alternative commercial and cultural worlds that developed outside, down below, and way out beyond mass consumer capitalism during the Cold War.

This is, one could argue, a return to an older historical narrative about how 1930s radicalism was repressed by 1950s McCarthyism, but then, perhaps out of the intensity of the repression itself, regenerated into the revolutions of the 1960s. Duncan, however, brings the narrative back into view with far more texture, using ample archival evidence to take us beyond the Don Draperian imagination into the crucible of the “rebel café” itself. There, Duncan argues, radical new ideas arose from the immediacy of concrete experiences. Take the case of Susan Sontag. Duncan uncovers how her influential theories of the “new sensibility” and “camp” arose directly from exploits she shared in the San Francisco queer underground. It was not some Madison Avenue advertisement that made Sontag think in new ways. It was going on zany, erotic adventures with figures such as Peggy Tolk-Watkins and Sontag’s sometime lover Harriet Zwerling (210-219). When Sontag eventually wrote, in Against Interpretation, that “in place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art,” she was, Duncan contends, thinking of places such as the famous Tin Angel club in San Francisco. Her cultural criticism cut right through mass consumer culture, raising up the underground ethos of the rebel café to more elevated intellectual climes (219).

Duncan’s book is full of these sorts of details, stories, and contexts. They gave rise, he believes, to key ideas in postwar American intellectual history. In this sense, we might say that he not only documents a lost history, but also proposes new ways of writing history itself. Rather than mechanistic and formulaic approaches, The Rebel Café offers a kind of “erotics of history,” to modify Sontag’s famous phrase. Duncan is curious to move past conventional tropes such as the historical “dialectic,” with its antiquated portrayal of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. To him, the stale use of the dialectic masks far more complex and intriguing dynamics. Even as Duncan himself sometimes reaches for the familiar handholds of the dialectical binary, he does, in his best writing, start to break free of its constraints. He hangs on to the dialectic, to be sure, writing: “If there is a single lesson to be learned from the Rebel Café, it is that the political/cultural dichotomy is a false one. They are always in a dialectic relationship, continually in tension, each breaking down and reconstituting the other” (235). Yet, more intriguingly, Duncan also leaps into new and far more intriguing theorizations of how history works when he writes:

The notion of culture as a dialectic, however, is too simplistic to capture the complexity of such sociocultural change. Rather than picturing polar opposites and a mediating synthesis, a better metaphor is that of various forms of culture as waves that crash onto the beach of society. Just as there are multiple and massive forces driving every wave, each is equally shaped by its landfall. No two waves are ever the same. And with each incoming crash, the beach itself is also reshaped, transformed at a granular level that only becomes recognizable when the shoreline changes enough to have to redraw the maps (237).

In passages such as this one, The Rebel Café becomes not only a contribution to the tale of postwar bohemian culture in the United States, but also an update to the broader methods of cultural history. This larger contribution comes, one might say paradoxically, from Duncan’s attention to specificity. It is only if we picture “various forms of culture as waves that crash onto the beach of society,” he writes, we can begin to see how “the beach itself is also reshaped, transformed at a granular level.”

As Duncan ably demonstrates in The Rebel Café, careful archival research and attention to the gritty details of lifeworlds and locales are essential to narratives of more amorphous historical change (and continuity we might add). Out of the places, the ideas. Out of the texture, the transformations. Out of the details, the development. Minutiae turn out to be more than miniscule factors. Culture perhaps turns out to be the base, not the superstructure. When it comes to history, things change, but they often change almost imperceptibly. We do not always notice them shifting when we look to the more typical scales of historical temporality. Yet, as Duncan argues about the effects of 1950s nightspots, “The molecular processes of conversation and critique, fundamental to public discourse and increasingly disseminated through print culture, slowly formulated opportunities for further, more visible demands for both individual and collective liberation” (77). Or as Bob Dylan put it, “There was music in the cafes at night and revolution in the air.”[10]

Ambiance can be a historical force. If not the zeitgeist, the atmosphere affects what happens next. From Stephen Duncan’s book, we learn how it mattered in the 1940s and 50s. The Rebel Café was always something more than just a vibe, but then became something even more than that.

[1] Bob Dylan, Chronicles: Volume 1 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 55. Alan Lomax was a folklorist and music documentarian who inspired Dylan and many others. See John Szwed, Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World (New York: Viking, 2010).

[2] Among other studies see W. T. Lhamon, Jr., Deliberate Speed: The Origins of a Cultural Style in the American 1950s, with a New Preface (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990; 2nd edition, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002); George Cotkin, Existential America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003; George Cotkin, Feast of Excess: A Cultural History of the New Sensibility (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); Robert Genter, Late Modernism: Art, Culture, and Politics in Cold War America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011); Grace Elizabeth Hale, A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); Kevin Mattson, Intellectuals in Action: The Origins of the New Left and Radical Liberalism, 1945-1970 (State College: Penn State Press, 2010); Leerom Medovoi, Rebels: Youth and the Cold War Origins of Identity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005); James J. Farrell, The Spirit of the Sixties: The Making of Postwar Radicalism (New York: Routledge, 1997); and Paul Boyer, By the Bomb’s Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985).

[3] Duncan’s study follows in the tradition of scholarship such as (just to name a few): John F. Kasson, Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978); Lewis A. Erenberg, Steppin’ Out: New York Nightlife and the Transformation of American Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984); Katy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986); Ann Douglas, Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s (New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1997); Randy McBee, Dance Hall Days: Intimacy and Leisure Among Working-Class Immigrants in the United States (New York: New York University Press, 2000); Burton W. Peretti, Nightclub City: Politics and Amusement in Manhattan (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007); and Sherrie Tucker, Dance Floor Democracy: The Social Geography of Memory at the Hollywood Canteen (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014).

[4] For the argument that the Red Scare marked the end of the Popular Front, see books such as Michael Denning’s The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Verso, 1996). Duncan focuses on culture rather than politics, but his book echoes studies emphasizing continuity, such as Maurice Isserman, If I Had a Hammer…: The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (New York: Basic Books, 1989).

[5] See Nan Alamilla Boyd, Wide-Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

[6] Quote from Bill Morgan, The Beat Generation in San Francisco: A Literary Tour (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2003), 50.

[7] This echoes the findings of Warren Bareiss, “Middlebrow Knowingness in 1950s San Francisco: The Kingston Trio, Beat Counterculture, and the Production of ‘Authenticity’,” Popular Music and Society 33, 1 (2010): 9–33.

[8] See arguments in Gitlin, The Sixties; Echols, Shaky Ground; Maurice Isserman and Michael Kazin, America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); and countless other studies.

[9] Todd Gitlin, The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (New York: Bantam Books, 1987); Alice Echols, Shaky Ground: The ’60s and Its Aftershocks (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002); and Thomas Frank, The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

[10]Bob Dylan, “Tangled Up In Blue,” Blood on the Tracks (Columbia PC 33235, 1974).

November 30, 2023

Rovings

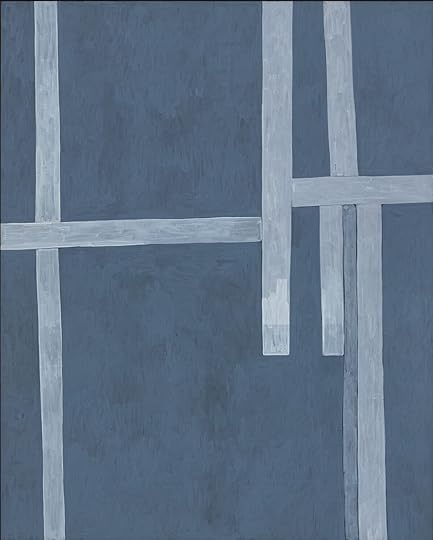

Sam Moyer, Large Payne (2023).SoundsBraim Abraham Chimbetu and the Orchestra Dendera Kings, The First CutBraim Abraham Chimbetu and the Orchestra Dendera Kings, SimukaiGamelan Angklung, Gamelan Gong Kebjar: Gamelan Music of BaliVarious Artists, Africa: Ghana—Ancient Ceremonies, Dance Music and SongsVarious Artists, Muriel’s Treasures: Vintage Calypso of the 1950s and 1960s, Vols. 1-12The Beatles, “Now and Then”Colorado Symphony and Colorado Symphony Chorus, Roy Harris: Symphony No. 3 / Symphony No. 4Rob Mazurka Exploding Star Orchestra featuring Roscoe Mitchell, Matter Anti-MatterIf We Burn with Vincent Bevins, The Dig PodcastHamas with Tareq Baconi, The Dig PodcastVarious Artists, African Flutes (Gambia)Don Gross, Bop Shop Live!: Joe Fonda QuartetGbáyá , Empire Centrafricain–Musique Gbáyá/Chants À PenserBa-Benzélé Pygmies, The Music Of The Ba-Benzélé PygmiesThe John A. and Ruby T. Lomax’s 1939 Texas Recordings, Been All Around This World podcastHush The Waves Are Rolling In: Lullabies from the Alan Lomax Collection https://alanlomaxarchive.bandcamp.com... X: The Life and Legacy of Malcolm X, Aria Code, 15 November 2023WordsAlexis Petridis, “‘He was treated like a holy figure’: why Captain Beefheart quit music for the easel,” Guardian, 28 November 2023David A. Bell, “The Year Europe Revolted,” The Nation, 28 October 2023Ethan Iverson, “Louis Armstrong Gets the Last Word on Louis Armstrong,” Nation, 30 October 2023Susie Ibarra, “Listening to Nature’s Equations in Sun and in Rain and especially in Community at PS21 Chatham,” Sonic Health Habit Journal, 22 July 2023George Hoare, “Pseudo-Leviathans,” Damage, 24 October 2023Thomas Furse and Andrew Gibson, “The Emergence of International Relations—The JHI in the Early Cold War: Virtual Issue 3 3,” JHI Blog, 16 October 2023Jordyn H. May, “‘Bears Do Not Roam the Streets’: Woman Suffrage and the Reimagining of the American West,” JHI Blog, 30 October 2023Niklas. Plaetzer, “The Volcano of Imagination: A Cornelius Castoriadis Forum,” JHI Blog, 14 June 2023Christi Jay Wells, “Embodied Listening and Structures of Power,” Americas: A Hemispheric Music Journal 31, 1 (2022), vii–xiiHomi K. Bhabha and Kate Fowle in conversation with Jessica Bell Brown, Kimberli Gant, Elena Ketelsen González and Xiaoyu Weng, “Conversations—Retroaction: On the 1993 Whitney Biennial and its place in the present,” Ursala 9, 18 November 2023Jason Resnikoff, “The Labor Movement Made Me a Labor Historian,” Labor Online, 8 November 2023Lucas Poy, “Shades of Internationalism: The Left’s Complex Relationship with Immigration,” Labor Online, 16 November 2023 Nikki Mandell, et. al., “Teaching Labor’s Story,” Labor OnlineNelson Lichtenstein, “Ultra Violence,” Dissent, 23 May 2023Ben Tarnoff, “Better Faster Stronger,” New York Review of Books, 9 September 2023Benjamin V. Allison, “How U.S. Failures in the 1970s Contributed to the Israel-Hamas War,” Made By History, Time, 17 November 2023Jasper Waugh-Quasebarth, Finding the Singing Spruce: Musical Instrument Makers and Appalachia’s Mountain ForestsLaToya Ruby Frazier, Flint Is Family in Three Acts, ed. Michal Raz-RussoPaul Fussell, Class: A Guide Through the American Status SystemColson Whitehead, Harlem ShuffleColson Whitehead, Crook ManifestoZadie Smith, The Fraud“Walls”Sam Moyer, Circle of Confusion @ Blum GalleryLoriel Beltrán, Total Collapse @ Lehmann Maupin SeoulPicasso: Drawing from Life @ Art Institute of ChicagoKelly Akashi, Encounters @ Henry Art Gallery Kim Jones @ The Box Isabel Nuño de Buen, Now and Away @ Chris Sharp Gallery

Border Crossings: Exile and American Modern Dance 1900-1955 @ New York Library of the Performing Arts

“Stages”Beth Bailey, “An Army Afire: How the US Army Confronted Its Racial Crisis in the Vietnam Era” @ Washington History Seminar, 9 November 2023Brooke L. Blower, “Americans in a World at War: Intimate Histories from the Crash of Pan Am’s Yankee Clipper” @ Washington History Seminar, 16 October 2023John Szwed with Nick Spitzer, Cosmic Scholar: Harry Smith @ Popular Music Books in Process Series, 21 November 2023Alan Bollard, “Economists in the Cold War: How a Handful of Economists Fought the Battle of Idea” @ Washington History Seminar, 2 October 2023Samuel Freedman, Into the Bright Sunshine: Young Hubert Humphrey and the Fight for Civil Rights @ Washington History Seminar, 12 October 2023The Nose: An Opera by Dimitri Shostakovich @ Royal Opera House, 16 June 2017ScreensThe War on DiscoLesley Keen, Orpheus and Eurydice excerptDead for a DollarBlue Eye Samurai

Sam Moyer, Large Payne (2023).SoundsBraim Abraham Chimbetu and the Orchestra Dendera Kings, The First CutBraim Abraham Chimbetu and the Orchestra Dendera Kings, SimukaiGamelan Angklung, Gamelan Gong Kebjar: Gamelan Music of BaliVarious Artists, Africa: Ghana—Ancient Ceremonies, Dance Music and SongsVarious Artists, Muriel’s Treasures: Vintage Calypso of the 1950s and 1960s, Vols. 1-12The Beatles, “Now and Then”Colorado Symphony and Colorado Symphony Chorus, Roy Harris: Symphony No. 3 / Symphony No. 4Rob Mazurka Exploding Star Orchestra featuring Roscoe Mitchell, Matter Anti-MatterIf We Burn with Vincent Bevins, The Dig PodcastHamas with Tareq Baconi, The Dig PodcastVarious Artists, African Flutes (Gambia)Don Gross, Bop Shop Live!: Joe Fonda QuartetGbáyá , Empire Centrafricain–Musique Gbáyá/Chants À PenserBa-Benzélé Pygmies, The Music Of The Ba-Benzélé PygmiesThe John A. and Ruby T. Lomax’s 1939 Texas Recordings, Been All Around This World podcastHush The Waves Are Rolling In: Lullabies from the Alan Lomax Collection https://alanlomaxarchive.bandcamp.com... X: The Life and Legacy of Malcolm X, Aria Code, 15 November 2023WordsAlexis Petridis, “‘He was treated like a holy figure’: why Captain Beefheart quit music for the easel,” Guardian, 28 November 2023David A. Bell, “The Year Europe Revolted,” The Nation, 28 October 2023Ethan Iverson, “Louis Armstrong Gets the Last Word on Louis Armstrong,” Nation, 30 October 2023Susie Ibarra, “Listening to Nature’s Equations in Sun and in Rain and especially in Community at PS21 Chatham,” Sonic Health Habit Journal, 22 July 2023George Hoare, “Pseudo-Leviathans,” Damage, 24 October 2023Thomas Furse and Andrew Gibson, “The Emergence of International Relations—The JHI in the Early Cold War: Virtual Issue 3 3,” JHI Blog, 16 October 2023Jordyn H. May, “‘Bears Do Not Roam the Streets’: Woman Suffrage and the Reimagining of the American West,” JHI Blog, 30 October 2023Niklas. Plaetzer, “The Volcano of Imagination: A Cornelius Castoriadis Forum,” JHI Blog, 14 June 2023Christi Jay Wells, “Embodied Listening and Structures of Power,” Americas: A Hemispheric Music Journal 31, 1 (2022), vii–xiiHomi K. Bhabha and Kate Fowle in conversation with Jessica Bell Brown, Kimberli Gant, Elena Ketelsen González and Xiaoyu Weng, “Conversations—Retroaction: On the 1993 Whitney Biennial and its place in the present,” Ursala 9, 18 November 2023Jason Resnikoff, “The Labor Movement Made Me a Labor Historian,” Labor Online, 8 November 2023Lucas Poy, “Shades of Internationalism: The Left’s Complex Relationship with Immigration,” Labor Online, 16 November 2023 Nikki Mandell, et. al., “Teaching Labor’s Story,” Labor OnlineNelson Lichtenstein, “Ultra Violence,” Dissent, 23 May 2023Ben Tarnoff, “Better Faster Stronger,” New York Review of Books, 9 September 2023Benjamin V. Allison, “How U.S. Failures in the 1970s Contributed to the Israel-Hamas War,” Made By History, Time, 17 November 2023Jasper Waugh-Quasebarth, Finding the Singing Spruce: Musical Instrument Makers and Appalachia’s Mountain ForestsLaToya Ruby Frazier, Flint Is Family in Three Acts, ed. Michal Raz-RussoPaul Fussell, Class: A Guide Through the American Status SystemColson Whitehead, Harlem ShuffleColson Whitehead, Crook ManifestoZadie Smith, The Fraud“Walls”Sam Moyer, Circle of Confusion @ Blum GalleryLoriel Beltrán, Total Collapse @ Lehmann Maupin SeoulPicasso: Drawing from Life @ Art Institute of ChicagoKelly Akashi, Encounters @ Henry Art Gallery Kim Jones @ The Box Isabel Nuño de Buen, Now and Away @ Chris Sharp Gallery

Border Crossings: Exile and American Modern Dance 1900-1955 @ New York Library of the Performing Arts

“Stages”Beth Bailey, “An Army Afire: How the US Army Confronted Its Racial Crisis in the Vietnam Era” @ Washington History Seminar, 9 November 2023Brooke L. Blower, “Americans in a World at War: Intimate Histories from the Crash of Pan Am’s Yankee Clipper” @ Washington History Seminar, 16 October 2023John Szwed with Nick Spitzer, Cosmic Scholar: Harry Smith @ Popular Music Books in Process Series, 21 November 2023Alan Bollard, “Economists in the Cold War: How a Handful of Economists Fought the Battle of Idea” @ Washington History Seminar, 2 October 2023Samuel Freedman, Into the Bright Sunshine: Young Hubert Humphrey and the Fight for Civil Rights @ Washington History Seminar, 12 October 2023The Nose: An Opera by Dimitri Shostakovich @ Royal Opera House, 16 June 2017ScreensThe War on DiscoLesley Keen, Orpheus and Eurydice excerptDead for a DollarBlue Eye Samurai

November 12, 2023

Pain-ter

Everything is all and one, anguish and pain, pleasure and death are no more than a process of existence. The revolutionary struggle in this process is a doorway open to intelligence.

— Frida Kahlo

Vanessa Severo’s one-woman show puts Friday Kahlo’s chronic pain at the center of the artist’s story. For Severo, who both wrote the play and performs it, the lifelong searing physical torment Kahlo suffered after surviving polio as a child and a terrible bus accident as a young woman defined her paintings, personality, and identity. Pain made Frida who she was, hence the title of Severo’s piece, …A Self Portrait.

The title of the play has a double meaning, however. Severo breaks out of character to explain to the audience her own story and how she came to understand Kahlo. It turns out there is more than one self portrait being painted here. The key notion from Kahlo for Severo has to do with feeling abnormal. A Kahlo quote both starts and ends the play:

I used to think I was the strangest person in the world, but then I thought there are so many people in the world, there must be someone just like me who feels bizarre and flawed in the same ways I do. I would imagine her, and imagine that she must be out there thinking of me, too. Well, I hope that if you are out there and read this and know that, yes, it’s true I’m here, and I’m just as strange as you.

The linkage of feeling “bizarre and flawed” becomes, for Severo, a way in to considering Kahlo, and herself, within efforts to expand the range of who counts as normal and able-bodied. Maybe the strange ones are in fact the most special and gifted. Just as Kahlo refused to let her physical pain define her as a person or a painter, Severo explains that she has not let a supposed disability (the fingers on one of her hands are not fully formed) stand in the way of excelling at sports, playing instruments, and whatever she has been interested in doing.

The focus on pain in Frida…A Self Portrait thus also, fascinatingly, brings out the presence of strength. Severo is a powerful performer, unafraid to flex her physical prowess on stage. She has a background in choreography and dance and at one point uses tremendous core strength to dramatize Kahlo’s pained situations, such as the strapped corset Kahlo needed to wear after spinal surgery (also referring to her childhood polio as well) as well as moments of emotional pain. One got to wondering: does pain require strength to be dramatized? Does strength, conversely, always involve some lurking, underlying quality of pain? What is the relationship between the realities of physical pain and its theatrical expression? How do we perform pain, or does it perform us? What is this anti-life force as it quickens, slowing the activity of the self yet also, strangely, powering it?

Severo’s creation is, after all, a one-woman show, which by definition requires a display of sheer endurance to deliver. And while the narrative of the play is fairly standard—flashbacks emerge during an interview with an architecture critic who has come to Kahlo’s famous Casa Azul in Mexico City—the play itself swerves in and out of the present as if to evoke the dizzying disorientation pain, and efforts to control it, produce. Severo moves in and out of various characters, shifting and dancing among two rows of costumes that hang from clotheslines behind her to retell the story of Kahlo’s life. We see dresses, some of Kahlo’s own iconic outfits, and the very recognizable wide suit of her lover and comrade Diego Rivera. Severo occupies Kahlo occupying many of these roles, but by the end of the performance, at last the artist is on stage alone by herself, with no more costumes or props or anything else but for herself and her pain. All has been stripped away—the art, Frida’s political investments, any social relationships, lovers, or family. We arrive at a person, solitary, in terrible, aching, paralyzing, and awful physical discomfort.

Pain is the defining modality of the play, at once bringing a clarity to the investigation in this self portrait. But also, at times, this intense focus on pain alone risks reducing the richness of Kahlo’s social and political commitments in the name of emphasizing her aloneness and her suffering. For instance, Severo portrays Kahlo in enormous pain when she discovers that her lover and husband Diego Rivera was lovers with her sister. Yet the emphasis on betrayal misses the depths of connection between the two artists. Both had many affairs, both came back to each other, and throughout all of it, both shared, in particular, a radical socialist political commitment that is perhaps the one key aspect of Kahlo’s life missing in the play’s portrayal.

The effectiveness of the play’s emphasis on pain is most on display when Severo interrupts the narrative repeatedly to strike poses of Kahlo in screaming silently, in agony, with relief only coming from self-administered shots of morphine. The repetition of this moment throughout the performance might begin to seem redundant—by the fourth time, one thinks ok, we get it, she is in enormous pain. Yet perhaps the repetition is the point. One thought of Elaine Scarry’s well-known philosophical reflections on the silent scream and the “body in pain”: “Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it, bringing about an immediate reversion to a state anterior to language, to the sounds and cries a human being makes before language is learned.” Here is where, in Severo’s dramatization, Frida Kahlo’s voice took shape: in this shocking silence, this prelinguistic sense of the self disintegrating and compensating back into personhood. On stage, Frida comes apart and puts herself back together over and over.

One cannot escape physical pain, and Frida Kahlo, a remarkable person of enormous will and strength, could not escape it either. There is no way for anyone to outthink pain, out-feel it, or outsmart it. It smarts. Pain is all-encompassing. Pain is no weak medicine. When one is in pain, the pain takes over. One is the pain. The pain is one. None of us, as mortal beings, can turn away from the unrelenting truth of pain experienced. The great accomplishment of Severo’s creation is that in its strong, solo approach to telling Frida Kahlo’s story, the playwright and actress insists we neither romanticize pain nor ignore it, but instead recognize its force. Triumph over pain is not the point here; acknowledging it is. Then carrying on the imperfect effort of repair, which produces surreal beauty, fierce communication, potent visions, a steady gaze staring right at you, a voice speaking to you even after the mouth that spoke it is gone: something strangely solid from a body of work.

November 7, 2023

Twisted Sister

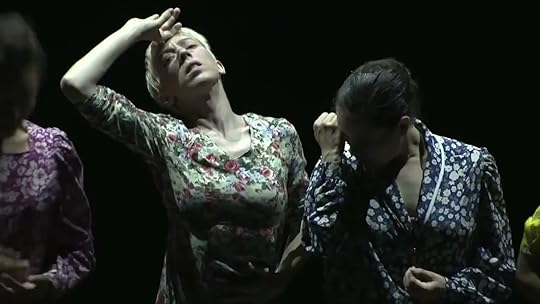

Wearing floral dresses, Leïla Ka and her dance company struck poses in Bouffées, one of three pieces they presented at the Sloan Performing Arts Center. With hands raised to foreheads, palms open, they looked up, backs arched. Then they pulled their stomachs in, curved their backs, rounded their shouldres as they clutched hands together across their bellies, almost in prayer, maybe in contrition, certainly in deep emotion.

Eventually, the dance took on an algorithmic quality—fractals of swaying, reaching, falling, rolling, rising again in a sequence at once complex yet never randomized. The movement was sudden, twitchy, paroxysmal, and jolting, but also highly structured and ordered. The gestures were almost violent yet intensely controlled, programmed, and arranged as they ping-ponged across the bodies of the performers in a kind of ricocheting effect. It was a marvelous correlation of collective expression across individual performers, a sense of variation within a tensile spring of repetition. Something here was external, structural, a shared oppression; yet it manifested individually, one body at a time.

These were largely poses of pain—the program notes describe a mysterious sorrow the women bear, a “grief” they seek to transform into “a medium of power and revival.” There was a hint of religious ecstasy to them as well, however. Most noticeable were unnoticeable forces at work. Someone had put the screws to these dancers. They expressed a sense of reacting to something coming at them: perhaps the world, patriarchy, racism, exploitation, alienation, suffering. Nonetheless, there was also a sense of reaction to something within: self-doubts, nagging suspicions, worried insecurities. These both were grabbed at, nabbed, clutched, assessed, and then usually swatted away.

Perhaps Bouffées, which means a puff of air, a breathe, a sudden fever, a rush, the sudden onset of intense feeling, was above all else a presentation of the way that internalization and externalization interact. Something from beyond them shocked these dancers. What it was we could not see. Yet we knew it was there. For it manifested from within them. In reaction, the stimulus glimpsed. Knocked down, these performers kept bouncing back to point out, beyond us, an onslaught that repelled them.

In the duet You’re the One We Love, two dancers—Jane Fournier Dumet and Leïla Ka herself—pursued a similar vocabulary of reaction full of sudden thrusts, twists, turns, gyrations, and assaults that almost seemed to become efforts to wrench the limbs of the body out of itself. Almost all the dance was duplicated across the two dancers, a virtuosic display of coordination, a kind of mirror stage fantasy, a duet that almost started to seem like a doubled solo until the end, when the movement shifted and one began to see connections between the two performers as they reached—at times warily, at times empathically—across parallel circuits.

In Pode Ser, Ka contrasted her former work as a hip hop dancer to classical ballet, again emphasizing comparisons of convulsive movement. The music followed her rapid shifts, shifting suddenly from soft classical symphonic tones to harsh electronic squibs and squalls. Even the costuming emphasized the dichotomy between ballet and hip hop: a pink dress made of something like chiffon over black pants that could have been straight out of Run-DMC’s Hollis, Queens streets.

There was a kind of bodily, sonic, and cultural disintegration at work in the piece. Arms pulled in to neck at the elbows pumping up and down, as if they were clipped wings; quick movements of the shoulders, neck, and head; crouching stances of confrontation; thrusts of the leg and foot and sometimes the hips; a ballerina’s spin and them the stepped territorial circling of a hip hop dancer’s feet. This was mostly a gestural language of contortion.

Gradually, a larger narrative proposed itself, something more like an unfolding progression of contrasts, repeated suggestions to the audience—and maybe even to the dancer herself—that we look closer at the juxtapositions, that we learn to live with them. Out of one form of culture—high European ballet—its supposed opposite appeared: street dance peeked out, asserted itself, only to dissolve back again into ballet.

The two forms never quite fused, but they did crackle in collision. Out of hybridity, a whole emerged, one that neither ever settled, nor totally broke apart. The fragmentation held. The sudden contrasts and the coughing, sputtering quality gave way to the potent possibilities of an amalgamation. To paraphrase the famous Paris 1968 phrase “below the paving stones, the beach!,” in this case it was below the pink ballerina dress, the track suit! Who would not want a world, after watching this performance, of both?

“Pode ser” means “could it be” in Portuguese and the three works presented by Leïla Ka all seemed to ask the question repeatedly: could it be? Could it be that things are this bad all around us, the world jabbing at these performers over and over again, putting them in pain? Could it be that they are so remarkably strong, resilient, forceful in response, not just persevering, but sometimes even seeming to flourish?

There was a core strength within the flinching of limbs, an enormous physical power that arose from the pressures that produce vulnerability. Hard gestures, stern responses, focused repercussions—the three works asserted that questions of “could it be” in the most utopian sense, the fantasy of reaching a new state of being more harmonious and hopeful, might most of all be coiled within the body under duress, taking it in and punching it back out again. To bend is not to break.

November 5, 2023

A Few Ells

Statue of Thomas Carlyle, Chelsea, London. Photo: George P. Landow.

Statue of Thomas Carlyle, Chelsea, London. Photo: George P. Landow.The most gifted man can observe, still more can record, only the series of his own impressions; his observation, therefore…must be successive, while the things done were often simultaneous; the things done were not in a series, but in a group. It is not in acted, as it is in written History: actual events are nowise so simply related to each other as parent and offspring are; every single event is the offspring not of one, but of all other events, prior or contemporaneous, and will in its turn combine with all others to give birth to new: it is an ever-living, ever-working Chaos of Being, wherein shape after shape bodies itself forth from innumerable elements. And this Chaos…is what the historian will depict, and scientifically gauge, we may say, by threading it with single lines of a few ells in length! For as all Action is, by nature, to be figured as extended in breadth and in depth, as well as in length…so all Narrative is, by its very nature, of only one dimension; only travels forward towards one, or towards successive points; Narrative is linear, Action is solid.

— Thomas Carlyle, “On History,” 1830

November 2, 2023

Award System

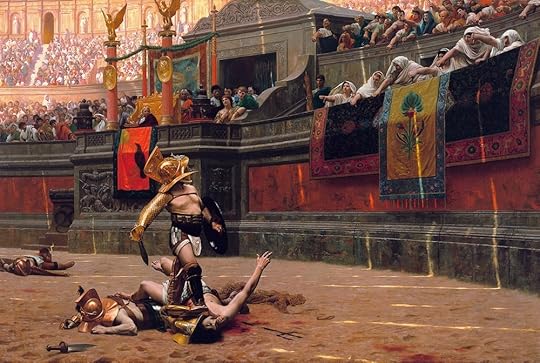

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Pollice Verso, 1872.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Pollice Verso, 1872.Once again, I reiterate my seemingly cranky, miserly (but in fact righteous and generous!) argument that prizes and awards are the bane of the academy—and maybe of society beyond the academy too.

At first, it sounds like I’m just being petty and jealous of those receiving such commendations, but as I watch yet another round of American Historical Association prizes announced and my own campus administration run a nomination process for various “persons of the year,” let me explain what I mean more carefully. I offer my perspective not to be a curmudgeon (ok, maybe a bit), but rather to ask: what is going on with the focus on prizes and awards? What cultural, political, and economic work are they doing?

My argument? The prize is not a prize at all. Rather, it is a device used by those in power to undermine collective flourishing and maintain control by encouraging atomized self-aggrandizement in place of putting resources into a robust public life and the common good. Prizes, doled out by the powerful, are paradoxically a means of producing a mood of scarcity and austerity. When you see a golden medal, it is gilded. You are actually receiving a poisoned chalice.

Why the mania for prizes? Why are those in charge of our professional organizations and institutions so keen on awarding just a few individuals prestige merely, well, for just doing their jobs (for scholars, the job is to research, teach, and steward our institutions and disciplines)?

Because the prize is not for the awardee, that’s why. The prize is almost always a self-congratulatory handout, given for the giver not the person to whom it is given. For the rich and powerful, or the managerial elite atop an institution or a profession for that matter, the ribbon, medal, plaque, or cash is a way to mark and separate, and to declare “I own you, you work for me.” To the sycophant go the spoils.

Which is to say that prizes and awards are also meant to keep everyone else in line. They divide and conquer, intimidate and reduce, create competition instead of cooperative solidarity.

To be clear, I am all for giving people money and status to do things. Fellowships, grants, and lots of money and support to do the work—yes to all that—but awards and prizes? All they do is make peers resentful, bitter, and demoralized.

Now I am sure I will possibly be awarded my own petard, as it were, for writing this, but so be it. Let’s have no more awards for scholarship and teaching and service. Down with excellence, innovation, disruption, and distinction. Up with competency, sustainability, stewardship, and solidity. Down with the star system, up with individuals thriving within more robustly funded, diversely rich, equitably distributed collective endeavors.

In the academy, if we wish to foster a world of discovery, knowledge, and understanding—classrooms for democracy, laboratories for advancement and improvement—let’s remove the trophies from the cases in the foyer. Let’s put the money into carrying on with the overall, ongoing work of social maintenance and intellectual enrichment. Let’s have no parade of prize winners in a true republic of letters. Instead, let’s have distinction within correspondences of mutuality.

October 31, 2023

Wall of Sound

Belcea Quartet.

Belcea Quartet.Listening to the Belcea Quartet perform Beethoven’s String Quartet in C minor, Béla Bartók’s String Quartet No. 1 in A minor, and Debussy’s String Quartet in G minor, the sonorities of the stringed instruments turned hushed, as if a padded with sonic feathers, but they were most exciting when the musicians pulled at their instruments, as if trying to rip the strings themselves off the necks. Solid edifices of sound emerged, walls made of something more solid than wood beams or steel girders. An architecture emerged.

Indeed, one might say that the sound of a string quartet offers a built environment for the ear to navigate: positive and negative spaces, walls and windows, corridors and doorways, roofs and plazas, gardens and sidewalks, alleyways and main thoroughfares, shafts and spires.

Where is this sonic architecture taking us? The strings assemble things. Maybe they present a purgatory zone, a liminal city, an intermediate terrain between the living and the dead. Maybe music as a whole is ultimately this effort to create a bridge, a skyway, an underpass, a mine, a hollow by which we might, for a moment, speak to ghosts, and hear, on vibrating strings, a faint response.

The string quartet presents this architectural fabrication as if it were created around a town square, but the piazza is abandoned. It is an empty space we move through, in which we might reach out for the departed for a moment. They are shadowy impressions, here but out of view, around corners, behind us, discernible only as a dim presence. If we turn around to chase, it is only as Orpheus did. They are transported to other realms, on invisible paths, contactless, vanished into nothingness. We find them gone.

Rovings

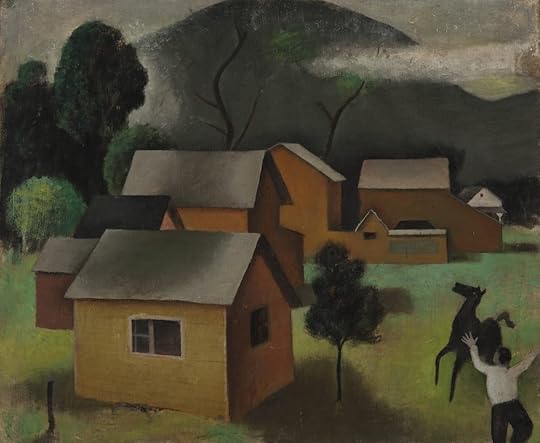

James Brooks, Woodstock (1931).Sounds75 Years of Folkways Records, NTS Radio, 22 October 2023Various Artists, Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958 – 1971Opal X, Environments Arthur Russell: The Peter Zummo Reflections, Roulette Tapes PodcastDoug Wieselman: Serious Juggling, Roulette Tapes PodcastSussan Deyhim: Ritual Futurism, Roulette Tapes PodcastJamie Branch, Fly or Die Fly or Die Fly or Die ((world war))Electronic India, BBC RadioVarious Artists, The NID Tapes: Electronic Music from India 1969-1972Various Artists, Bolinus Brandaris: Flamenco from the Bay of CadizVarious Artists, Listen All Around: The Golden Age of Central and East Africa Neil Hamburger featuring AJ Lambert, “Sleeping For Free”Asmus Tietchens + David Lee Myers, ArcsDavid Lee Myers & Toshimaru Nakamura, ElementsAlasdair Roberts, Grief in the Kitchen and Mirth in the HallMatmos, Return to ArchiveTimber, Part of What You HearCaña Dulce y Caña Brava, AccentsGonora Sounds, Hard Times Never KillAndrew Bird, Outside ProblemsBill Evans Trio, Portrait in JazzWilco, CousinDevo, Fifty Years of De-EvolutionJay Farrar and Ben Gibbard, One Fast Move or I’m GonePhoebe Bridgers , PunisherBetter Oblivion Community Center, Dead OceansSufjan Stevens, JavelinWordsZadie Smith, “The Instrumentalist,” New York Review of Books, 19 January 2023Hugh Morris, “India’s Early Electronic Music From the ’70s Is Finally Being Released,” New York Times, 2 October 2023Jon Pareles, “Devo’s Future Came True,” New York Times, 12 October 2023Richard Scheinin, “How Sam Rivers and Studio Rivbea Supercharged ’70s Jazz in New York,” New York Times, 22 September 2023Chris Lehmann, “Americans Have Already Lived Through a Shutdown,” The Nation, 29 September 2023Judith Butler, “The Compass of Mourning,” London Review of Books, 19 October 2023Joshua Leifer, “Toward a Humane Left,” Dissent, 12 October 2023Gabriel Winant, “On Mourning and Statehood: A Response to Joshua Leifer,” Dissent, 13 October 2023 Joshua Leifer, “A Reply to Gabriel Winant,” Dissent, 13 October 2023 Various Artists, “Open Letter,” New York Review of Books, 14 October 2023Isaac Butler, “American Theater Is Imploding Before Our Eyes,” New York Times, 19 July 2023Jason Farago, “Why Culture Has Come to a Standstill,” New York Times Magazine, 10 October 2023Barbara Y. Welke, “When All the Women Were White, and All the Blacks Were Men: Gender, Class, Race, and the Road to Plessy, 1855–1914,” Law and History Review 13, 2 (October 1995), 261–316Liette Gidlow, “The Sequel: The Fifteenth Amendment, The Nineteenth Amendment, and Southern Black Women’s Struggle to Vote,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 17, 3 (July 2018), 433–49Mack McCormick and John William Troutman, Biography of a Phantom: A Robert Johnson Blues Odyssey.Kazuo Ishiguro, The Remains of the DayOrhan Pamuk, Snow“Walls”Cellphone: Unseen Connections @ Smithsonian National Museum of Natural HistoryAmanda Turner Pohan, between Scylla and Charybdis @ RITHenry Taylor, B Side @ Whitney Museum of ArtAnousha Payne, Tender Mooring @ Deli GalleryDoris Salcedo @ Fondation BeyelerMany Wests: Artists Shape an American Idea @ Smithsonian Museum of ArtNoël Dolla, Tulle/Dye, 1969-2023 @ Ceysson & BénétièreJane Wilson, Atmospheres @ DC Moore GalleryRobert Motherwell, Pure Painting @ Modern Art Museum Of Fort Worth, TexasKathy Ruttenberg, Twilight in the Garden of Hope @ Lyles & KingMusical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies @ Smithsonian American Art MuseumJames Brooks, A Painting Is a Real Thing @ Parrish Art MuseumDavid Smith, Songs of the Horizon @ The Hyde CollectionCyle Warner, Weh Dem? De Sparrow Catcher? @ Welancora Gallery“Stages”Mad Shak, Ex/Body: strike, vibrate, shatter is today @ Studio5, 22 October 2023Amanda Turner Pohan, Alexa Echoes @ EMPAC (Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center) at Rensselaer, 4 February 2021 Eric Vloeimans and Will Holshouser @ Bop Shop Records, 19 October 2023Los TexManiacs @ The Kennedy Center, 20 September 2018Max and Josh Baca and Los Texmaniacs Conjunto Underground @ Mi Tierra, 29 April 2022Max and Josh Baca and Los TexManiacs @ Bosmans, San Antonio, 24 February 2023Los TexManiacs @ the Rhythm & Roots Fest, Charlestown, RI, 4 September 2022Eastman Ranlet Series Presents: Belcea Quartet @ Kilbourn Hall, Eastman School of Music, 22 October 2023Screens1923NotoriousBeau TravailThe French ConnectionThe Grey ManState of PlayThe Spirit of ’45The Pigeon TunnelMartin Hawk, A Litany for Survival

James Brooks, Woodstock (1931).Sounds75 Years of Folkways Records, NTS Radio, 22 October 2023Various Artists, Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958 – 1971Opal X, Environments Arthur Russell: The Peter Zummo Reflections, Roulette Tapes PodcastDoug Wieselman: Serious Juggling, Roulette Tapes PodcastSussan Deyhim: Ritual Futurism, Roulette Tapes PodcastJamie Branch, Fly or Die Fly or Die Fly or Die ((world war))Electronic India, BBC RadioVarious Artists, The NID Tapes: Electronic Music from India 1969-1972Various Artists, Bolinus Brandaris: Flamenco from the Bay of CadizVarious Artists, Listen All Around: The Golden Age of Central and East Africa Neil Hamburger featuring AJ Lambert, “Sleeping For Free”Asmus Tietchens + David Lee Myers, ArcsDavid Lee Myers & Toshimaru Nakamura, ElementsAlasdair Roberts, Grief in the Kitchen and Mirth in the HallMatmos, Return to ArchiveTimber, Part of What You HearCaña Dulce y Caña Brava, AccentsGonora Sounds, Hard Times Never KillAndrew Bird, Outside ProblemsBill Evans Trio, Portrait in JazzWilco, CousinDevo, Fifty Years of De-EvolutionJay Farrar and Ben Gibbard, One Fast Move or I’m GonePhoebe Bridgers , PunisherBetter Oblivion Community Center, Dead OceansSufjan Stevens, JavelinWordsZadie Smith, “The Instrumentalist,” New York Review of Books, 19 January 2023Hugh Morris, “India’s Early Electronic Music From the ’70s Is Finally Being Released,” New York Times, 2 October 2023Jon Pareles, “Devo’s Future Came True,” New York Times, 12 October 2023Richard Scheinin, “How Sam Rivers and Studio Rivbea Supercharged ’70s Jazz in New York,” New York Times, 22 September 2023Chris Lehmann, “Americans Have Already Lived Through a Shutdown,” The Nation, 29 September 2023Judith Butler, “The Compass of Mourning,” London Review of Books, 19 October 2023Joshua Leifer, “Toward a Humane Left,” Dissent, 12 October 2023Gabriel Winant, “On Mourning and Statehood: A Response to Joshua Leifer,” Dissent, 13 October 2023 Joshua Leifer, “A Reply to Gabriel Winant,” Dissent, 13 October 2023 Various Artists, “Open Letter,” New York Review of Books, 14 October 2023Isaac Butler, “American Theater Is Imploding Before Our Eyes,” New York Times, 19 July 2023Jason Farago, “Why Culture Has Come to a Standstill,” New York Times Magazine, 10 October 2023Barbara Y. Welke, “When All the Women Were White, and All the Blacks Were Men: Gender, Class, Race, and the Road to Plessy, 1855–1914,” Law and History Review 13, 2 (October 1995), 261–316Liette Gidlow, “The Sequel: The Fifteenth Amendment, The Nineteenth Amendment, and Southern Black Women’s Struggle to Vote,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 17, 3 (July 2018), 433–49Mack McCormick and John William Troutman, Biography of a Phantom: A Robert Johnson Blues Odyssey.Kazuo Ishiguro, The Remains of the DayOrhan Pamuk, Snow“Walls”Cellphone: Unseen Connections @ Smithsonian National Museum of Natural HistoryAmanda Turner Pohan, between Scylla and Charybdis @ RITHenry Taylor, B Side @ Whitney Museum of ArtAnousha Payne, Tender Mooring @ Deli GalleryDoris Salcedo @ Fondation BeyelerMany Wests: Artists Shape an American Idea @ Smithsonian Museum of ArtNoël Dolla, Tulle/Dye, 1969-2023 @ Ceysson & BénétièreJane Wilson, Atmospheres @ DC Moore GalleryRobert Motherwell, Pure Painting @ Modern Art Museum Of Fort Worth, TexasKathy Ruttenberg, Twilight in the Garden of Hope @ Lyles & KingMusical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies @ Smithsonian American Art MuseumJames Brooks, A Painting Is a Real Thing @ Parrish Art MuseumDavid Smith, Songs of the Horizon @ The Hyde CollectionCyle Warner, Weh Dem? De Sparrow Catcher? @ Welancora Gallery“Stages”Mad Shak, Ex/Body: strike, vibrate, shatter is today @ Studio5, 22 October 2023Amanda Turner Pohan, Alexa Echoes @ EMPAC (Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center) at Rensselaer, 4 February 2021 Eric Vloeimans and Will Holshouser @ Bop Shop Records, 19 October 2023Los TexManiacs @ The Kennedy Center, 20 September 2018Max and Josh Baca and Los Texmaniacs Conjunto Underground @ Mi Tierra, 29 April 2022Max and Josh Baca and Los TexManiacs @ Bosmans, San Antonio, 24 February 2023Los TexManiacs @ the Rhythm & Roots Fest, Charlestown, RI, 4 September 2022Eastman Ranlet Series Presents: Belcea Quartet @ Kilbourn Hall, Eastman School of Music, 22 October 2023Screens1923NotoriousBeau TravailThe French ConnectionThe Grey ManState of PlayThe Spirit of ’45The Pigeon TunnelMartin Hawk, A Litany for Survival

October 27, 2023

If You’re Going to San Francisco

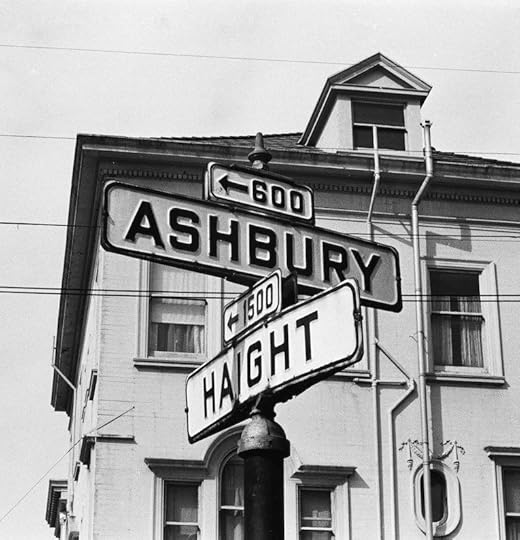

Reflections on a Summer 2023 Scholar-in-Residence experience at the SF Heritage Doolan-Larson Building in the Haight Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco. From SF Heritage News, LI, 3 (October-December 2023).

In my first book, The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture (Oxford University Press, 2013),and in many subsequent essays, articles, and talks, I examined the ways in which the Haight Ashbury became a globally significant place in the late 1960s. So, it seemed like fate that when I got into a taxi at San Francisco International airport in August of 2023 and said to the driver: “Take me to the corner of Haight and Ashbury.” Here I was reenacting the pilgrimage so many took to in the 1967 Summer of Love. However, I was not seeking to wear flowers in my hair (what hair?). I was in the Bay Area to serve as scholar-in-residence at San Francisco Heritage’s Doolan-Larson Building, located right at the historic corner of the Haight Ashbury neighborhood. The residency allowed me to conduct archival research on two projects: Anna Halprin‘s 1969 dancework Ceremony of Us, which saw her Bay Area-based Dance Workshop collaborate with an African American dance company in Watts, Los Angeles to explore race relations in America; and a proposed volume of selected essays by the countercultural social critic Theodore Roszak that I am developing with co-editor Peter Richardson, author of books about the Grateful Dead, Ramparts magazine, Hunter S. Thompson, Carey McWilliams, and currently working on a history of Rolling Stone magazine’s first 10 years.

The Halprin research took place in the archives of the Museum of Performance and Design and connects to an essay I am working on about how the 1960s countercultural milieu has things to teach us—some painful, some hopeful—about struggles over black-white cross-racial solidarity in today’s post-Black Lives Matter world.

The Roszak research reexamines this important but often forgotten writer. Roszak penned The Making of the Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition, a best-selling book from 1969 that gave the phenomena of so-called hippies in the Haight and elsewhere its very name. His papers at Stanford University’s Special Collections Library provide a vivid sense of Roszak’s wide-ranging work. By developing a volume of selected essays, Peter Richardson and I seek to show the breadth of Roszak’s critical perspective on everything from the peace movement to environmental issues to gender equality to the politics of science to the early Silicon Tech industry, and much more. Here is a thoughtful voice from “back then,” starting in the 1960s, that has something to say to the twenty-first century—even to those who care not one whit about hippies and the counterculture.

Being at the Doolan-Larson Building while conducting this research greatly enriched it, and not only for sheer ambiance. I was able to do things such as talk at length with artist-in-residence Seth Eisen, who with his group Eye Zen Presents was presenting a site-specific theatrical walking tour around the Haight about the amazing performer Sylvester. Seth and I were able to discuss the intersections of historical research and theatrical performance. It was a reminder that we access history from many angles. Particularly with the experiential qualities that mark the history of the Haight, hippies, and the broader counterculture, it is imperative we do so.

Overall, I was thrilled to get to spend two weeks in Norman Larson’s former apartment at the Colonial Revival building he owned, which housed important late 1960s shops such as Peggy Caserta’s Mnasidika, the clothing store that gave the world bell bottoms. It was an inspiring base from which to pursue my research in the City by the Bay.

Kramer-Doolan-Larson-SF-Residency-Halprin-Rozak-Summer-2023PDF.