Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 8

August 7, 2024

Let’s Get Uncreative

X-posted from the Journal of Social History, 2024.

Creativity, Samuel W. Franklin writes, is overrated. The “creatives,” so celebrated by urban

studies scholar Richard Florida and others as saviors of the postindustrial economy, turn out

to have rather banal origins. This, Franklin contends, is precisely why the term creativity is

so fascinating. In The Cult of Creativity: A Surprisingly Recent History, the historian argues

that during the decades after World War II, the concept arose not among artists, bohemians,

or hipsters, but rather in the precincts of corporations, advertisers, management gurus, scientists,

engineers, educators, and, later, “human-centered” designers. They sought to identify

an ineffable quality of human activity and identity—a style and sensibility, maybe even a

how-to program—that could resolve the tensions, soothe the anxieties, and assure the validity

of both their particular professional fields and the larger Cold War society.

Franklin has come neither to praise creativity, nor quite to bury it, but rather to unearth

its strange story. Instead of joining the “cult of creativity” or polemically condemning it,

Franklin chooses to historicize the term. His well-written, even-tempered narrative, excellently

grounded in rarely examined archival sources, does not go so far as to argue that creativity

was a fantastical creation, fabricated whole cloth, but Franklin does want us to

understand how creativity became a fetishized ideal. Creativity was an amorphous term, he

notices, that was often used mostly to name a problem—one could even say to create a

problem where there was not one—in order to justify the need for a solution. By probing its

history since World War II, he explains how the concept was both “forged as a psychological

solution to structural problems” in postwar America and served the specific institutional or

ideological needs of various professions (208). Creativity, he argues, became an ideal

because it could mediate “a nagging tension between the utilitarian and the humane or transcendent”

as well as offer a way to handle feelings of both “optimism and pessimism” concerning

the future (14-15). It provided a way to balance out “elitist and egalitarian

tendencies” in American life (16). It was “heroic yet democratic, romantic yet practical,”

Franklin writes. It “sought to harmonize the economic and inner self” (100). Those who

formed its cult, such as the very weird but successful Synectics managerial consulting group, wanted to help industrial firms achieve a “disciplined freedom, an intoxicating steadiness, a

predictable gamble, an ephemeral solidity” through brainstorming sessions that sometimes

bordered on the bizarre. These activities, Franklin argues, galvanized “the paradoxes at the

heart of postwar America” (116).

Over the course of nine chapters, Franklin explains how creativity arose so that its cultists

might have their liberated, individualist, dissident cake and eat their conformist mass society

American superpower abundance too. He explores the ideas of psychoanalytic theorists in

the human potential movement such as Abraham Maslow and Rollo May. They developed

more sophisticated approaches to creativity as a means for people to flourish despite the

existential threats of the Atomic Age, yet creativity also fit quite easily into existing regimes

of Big Science, hyper-rationalization, military-industrial coordination, and even the making

of the Bomb itself.

Psychologists such as Joy Paul Guilford, Frank Barron, and Calvin Taylor found ways to

measure and test creativity, a rather paradoxical but well-intentioned task. Education

researchers such as E. Paul Torrance drew upon their work to forge new approaches to

assessing students, opening up concepts of intelligence and giftedness beyond rote memorization.

Navigating the tricky waters of postwar public educational politics, Torrance “deftly

hitched the Cold War liberal critique of conformity to conservative fears of mediocrity and

civilizational decline,” Franklin writes (132). Placing the slippery notion of creativeness on

quantitative scales of measurement, psychologists and educators not only addressed larger

social concerns about creeping “soft totalitarianism” after World War II, but also found ways

to thrive professionally amidst questions about the validity of their own fields as humane

pursuits within a technocratic Cold War milieu.

Similarly, creativity allowed advertisers to remedy intra-professional questions about the

ethics of their profession, which had been heavily criticized by the likes of Vance Packard as

a mode of devious manipulation. They could claim a place as creative culturemakers rather

than cold-blooded connivers. Like psychologists, educators, and advertising firms,

technological-driven corporations, engineers, and scientists offered what we might call a

“vibe” of creativity to shift their reputations. Instead of creating products, they enacted the

creative process. So what if their rockets could destroy the world? Represented by colorful,

almost Cubist-like advertisements, missiles suddenly looked part of a pastoral, aestheticized

landscape of ingenuity and innovation. “Mix imagination with Alcoa Alumnias and see

ceramics do what ceramics never did before!” one ad declared, continuing, “A case in point:

Missile designers needed nose cone material transparent to electronic impulses and able to

withstand a holocaust of heat” (181). People might not survive, but creativity made that

seem like a sterile, talentless thing to point out.

It must be admitted that Franklin’s book is not always revelatory, but perhaps that is fitting

for a critique of the cult of creativity. There is no bold new theory or thesis proposed to

rival or replace the likes of Thomas Frank’s groundbreaking The Conquest of Cool: Business

Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism, which hovers over Franklin’s study.

Instead, the author calmy and cogently adds detail and specificity to critiques of Cold War

American culture developed as early as 1950, when sociologists David Riesman, Nathan

Glazer, and Reuel Denney described what they thought was a dramatic shift from an inner-

directed American style of tradition and character to an outer-directed one of personality.

Sociologist Daniel Bell would later, in the 1970s, famously argue that this transition resulted

from “the cultural contradictions of capitalism,” which demanded discipline in the work lives

of Americans to produce wealth, but at the same time hedonism, libidinal gratification, and therapeutic dependency to drive a mass consumer economy. For Bell, along with historians

such as Christopher Lasch and Warren Susman, as well as many others, the tension between

an older, producer-oriented America dominated by Protestant-derived, republican values of

self-denying thrift and a newer, more secular world of destabilizing but tantalizing plenitude

and pleasure created great cultural challenges. Creativity, Franklin contends, emerged as one

way to address them. “The concept of creativity served as a psychological fix for the structural

contradictions of postwar America,” he concludes. “It reconciled a newfound individualism—which

itself contained progressive, liberal, and reactionary ingredients—with the

seemingly incontrovertible facts of mass society” (183).

Franklin’s argument is convincing, but it mostly recapitulates the going theory of how culture

has functioned in United States history. Call it the “resolving paradoxes” or “reconciliation”

or “both resisted and reinforced” thesis. Cultural forms, in this argument, emerge

triumphant because they solve conundrums. One sometimes wonders, reading Franklin’s

book, if his sources have something more to offer us in terms not only of fitting creativity

into existing interpretations of American cultural history, but also revising them. Could The

Cult of Creativity have been a bit more, well, creative in this regard? Perhaps.

In the meantime, Franklin’s book offers a genealogy of the concept for post-millennial

generations seeking to understand the roots of their own era. Going back to the postwar

years, he tries to put the cult of creativity to rest in the contemporary moment, rejecting its

worst excesses. In his thoughtful conclusion, Franklin proposes we set aside innovation, disruption,

rule-breaking, and postures of infantile, rebellious nonconformity. Instead, he calls

for more collective political will, solidarity, sociality, maturity, and sustainability. Down with

the cult of creativity, up with the actual human creative capacity for better carework, maintenance,

and competency!

July 31, 2024

Germinating

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Skull (Nature morte au crâne), 1890-1893.

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Skull (Nature morte au crâne), 1890-1893.The nourishing fruit of the historically understood contains time as a precious but tasteless seed.

— Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History

Tiger’s Leap Into the Past

Fashion has a flair for the topical, no matter where it stirs in the thickets of long ago; it is a tiger’s leap into the past. This jump, however, takes place in an arena where the ruling class give the commands. The same leap in the open air of history is the dialectical one, which is how Marx understood the revolution. …

—Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History

July 28, 2024

Cold War Tones

X-posted from the Society for US Intellectual History Book Review.

These psalms are a simple and modest affair / Tonal and tuneful and somewhat square / Certain to sicken a stout John Cager / With its tonics and triads in B-flat major. / But there it stands—the result of my pondering / Two long months of avant-garde wandering— / My youngest child, old-fashioned and sweet. / And he stands on his own two tonal feet.

— Leonard Bernstein, on his composition, Chichester Psalms (1965)

In 1963, Leonard Bernstein wondered if it was appropriate anymore to create traditional classical music. “Is this world of NATO and Birmingham and the Faith-7,” he asked, mentioning symbols of the Cold War, Civil Rights Movement, and the Space Race, “a world in which a composer is forbidden to write a melody?” He wanted to know if Americans were “still living in a world where an octave leap upward implies a sense of yearning, or reaching? Or is it become only an intervallic symbol?” Bernstein worried that the political and social situation had completely severed musical signification from emotional resonance. Were sounds now just sounds, nothing more? Or could they still summon feelings? In the Atomic Age, he feared, it was no longer so clear. An alienating, cold, rationalized technic had replaced soulful expressions of “human expressivity” (Ansari, 176).

As Emily Abrams Ansari and Phillip M. Gentry reveal, music might have felt pulverized by history during the Cold War, but it still mattered. Neither its emotional, nor its social meaning had not been drowned out entirely by nuclear bomb testing or the sounds of firehouses turned on protesters or the roar of space rockets. Instead, music came to figure dramatically in issues of both collective cultural nationalism and individual self-identity. Whether one looks at Bernstein’s tonal crisis or John Cage’s infamous four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence, whether one recovers the State Department-sponsored Americanisms of William Schuman, Virgil Thomson, Roy Harris, or Aaron Copland, as Ansari does, or the manifestations of a new kind of identity politics in early doo-wop, the whiteness of Doris Day, the presence of Asian peoples in musical theater, and Cage’s daring composition, as Gentry does, one discovers high stakes for musical expression: “intervallic sounds” and other modes of making music came to represent far more than the mere difference between two notes.

Both Ansari and Gentry want to know more about music’s ideological twists and turns in the United States after World War II. Ansari is curious to better understand how art music composers adjusted their respective expressions of “musical Americanism” within the changing Cold War milieu. She discovers they often compromised their sense of liberal or socialist ideologies to the point of abandoning any strong resistance to the power of consensus anticommunism that dominated the larger society at the time, yet they were also able occasionally to incorporate alternatives and even sometimes resistance into their cultural politics. Gentry is less concerned with music’s relationship to state power than its connections to the rise of identity politics in Cold War America. Like Ansari, he sees plenty of accommodation as well, but more moments of rebellion, dissent, and opposition.

For Ansari, modes of composing music were themselves highly political by the Cold War decades. Whether a composer chose to write music with traditional, familiar harmonic relations or, by contrast, adopt the more dissonant, experimental twelve-tone technique invented by Arnold Schoenberg signaled nothing less than whether that person believed in capitalism or communism, the American Way or its Soviet counterpoint. Clefs on the staff notated more than just what sounds to make, what register in which to play the music. Instead, notes imagined nations.

For Gentry, not just composition, but the performance of music is crucial to understanding its relationship to Cold War identity politics. Subtle vocal tonal colorations and timbres articulated class, racial, and ethnic identities as older moorings of tradition and gave way to the modernist, assimilationist mix of the post-World War II milieu. As social scientists such as Erik Erickson were busy theorizing the very notion of identity itself in the 1950s, so too musicians and their audiences were theorizing the self. Erickson used psychoanalysis; they used music. All sought to navigate what it meant to “discover” oneself in the Cold War world.

These books are good examples of scholarship that does not break new ground so much as take us more deeply into topics first broached by other groundbreaking scholars. Ansari’s book is written very much in the wake of work such as Carol Oja’s studies of American musical modernity.[1] Gentry’s book draws upon the innovative interpretations of music and identity put forward by Timothy Taylor.[2] Both authors write under the influence of Nadine Hubbs’ innovative musicological research into gayness during the Cold War.[3] Nonetheless, despite being follow-ups rather than breakthrough hits, the two books bring us into the fine-tuned (or with some of the music, not-so-finely tuned) dimensions of Cold War cultural history.

Both books remind us that tone and timbre, musical style and sound, matter to history. Could we not say that all historians chase the tone and timbre of an era as much as its basic facts? Music is empirical data too, we might notice, although accessing what historical information it has to offer us can be tricky business. Music catches a bit of the zeitgeist, some of the spirit and mood of the past. What was the temperament of the times? How did history modulate? Did it blend or did it growl? What changed, altering meter or tonality? What marched forward, staying in the same rhythm? What were the dissonances of the day and what still resonates now? Tone and timbre indeed have as much to teach us about the past as political events, economic forces, or specific social conditions. Music can help us access the more ephemeral qualities of the past. Amplitudes involve attitudes, and these are often as historically revealing as any presidential election or congressional debate or war or economic interaction or struggle in the streets. Historians must try to catch the texture as well as the substance of the times if they are to get history right. And sometimes the texture is the substance. Such was the case during the Cold War, when the smallest details as well as the largest structures of life became swept up in geopolitics.

By asking us to listen more closely and carefully to musical expression, Ansari and Gentry allow us to hear far better the howls that delivered the Cold War’s chill. Ansari helps us see that the seemingly arcane question of whether composers should embrace the modernist compositional theory of serialism became a pressing question of cultural nationalism and Cold War contestation. Composers dedicated to forging a “musical Americanism” such as Howard Hanson, William Schuman, Virgil Thomson, Roy Harris, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein had to adjust to the divisive dualities of the Cold War. “With their music intimately intertwined with the idea of America,” Ansari writes, “each of the Americanists had to decide whether to allow their music to be aligned with ‘consensus’-era conceptions of American identity or whether to pursue a different aesthetic path—perhaps the more prestigious path that serial and atonal composers were promoting.” To move in the latter, more avant-garde direction, however, meant confronting the tricky, sometimes outright hostile politics of the Cold War: composers “were forced to deal with accusations of un-American activity against leading musical Americanists—a shocking development, given their aesthetic Americanism.” The very use of more experimental compositional tactics posed professional and political dangers for these composers, “even those who were stridently anti-Communist” (21).

Ansari is quite attuned, as it were, to the subtle, sometimes ironic ways each composer navigated the treacherous dissonances of the Cold War. Sometimes they took advantage of the intensification of cultural struggles to access resources of governmental funding and influence; at other times, they backed away from state power. Howard Hanson, William Schuman, and Virgil Thomson each forged what Ansari calls “liberal pragmatic” paths. Hanson and Schuman “used a European-inspired but Europe-rejecting repertoire to win the respect of Europe” (50) while Thomson’s “Cold War music sought a similar balance between the artistic symbols of individual and community—between radical experimentalism and accessible tonal writing, between new and old, between the cerebral and the world of the emotions—even as his style was increasingly crowded out by the growing prestige of other approaches” (92). Perhaps less well-known than Thomson was Roy Harris. His “story is not simply the familiar narrative of an enthusiastic Depression-era leftist who became disillusioned by the stifling, sometimes oppressive, centrist political culture of the 1950s” (125). Instead, it was a tale of a composer who clung to the dream of writing American nationalistic music and surprisingly discovered more affiliations with composers and state cultural policy in the Soviet Union in pursuit of this project than among American audiences. His “musical Americanism” paradoxically brought him closer to Russia.

The more famous and successful Aaron Copland, meanwhile, honed a “cultural nationalism” that “was more a product of his cosmopolitanism than an intense patriotism.” For Copland, “deliberately sounding American” was, ideally, “an effective means to garner international attention for American composers,” however his “ultimate goal was always, he said, to be a ‘citizen of the Republic of Music.'” (134). Other scholars contend that the Cold War compromised Copland’s successes, but Ansari begs to differ. “By overtly disavowing the Soviet other by turning away from an accessible nationalism and allowing his ideologically antiexceptionalist music to be associated with Cold War exceptionalism,” she writes, “Copland could save the reputation of his music and continue to build connections through his art.” Cold War Americanism tried to use him for nationalistic ends, but, Ansari believes, he was also able to use it for internationalist ones. By “erasing controversial biographical features from his self-presentation and allowing his repertoire to help promote American exceptionalism, Copland was actually very well-positioned to bring musical Americanism to new audiences and to use music to help improve international understanding,” she concludes (160).

The effort to have one’s exceptionalist American cake and eat one’s internationalist universalism too also marked the career of Copland’s protégé Leonard Bernstein, but the latter figure struggled more than Copland to negotiate the tensions between musical Americanism and cosmopolitanism, particularly as the more conformist 1950s gave way to the tumultuous 1960s. “Although Bernstein used every mechanism at his disposal…to imagine and promote a different, more progressive future for the United States,” Ansari explains, “his career peaked at a particularly problematic moment in which to realize such an agenda” (164). Trying to make sense of the Cuban Missile Crisis, John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the Civil Rights Movement, and the escalation of US military and political involvement in Vietnam, “Bernstein offered a striking and bold challenge to Cold War binaries—both musical and political.” Yet his “attempts to break down such oppositions were complicated, and even compromised, by his promotion of cultural nationalism.” Musical theater provided a means by which Bernstein “advanced a progressive musical Americanism” by combining popular theater and art music to reshape cultural hierarchies and advocate for egalitarian social change (186). By contrast, classical composition proved a more difficult form for Bernstein’s political and social goals.

In wonderfully close interpretations of his musical tactics in Symphony No. 3 (1963) and Chichester Psalms (1965), Ansari documents how the composer confronted “the very real limits of Cold War dissent” (189). As much as he tried to expand Copland’s pursuit of cosmopolitan goals by way of nationalistic means, Bernstein could not transcend the potency of Cold War American nationalism and exceptionalism. He wanted to foster a community above the divide between the capitalist West and communist East, but with “his own two tonal feet” he could not confidently span the divide between the United States and the Soviet Union (181). Instead, his music fell back into a nationalistic project. Tone—even Bernstein’s occasional incorporation of a Schoenbergian row of twelve of them—was no match for the geopolitical moment. The exceptionalism of musical Americanism proved louder than any subtler effort to achieve a global cosmopolitanism. The American state had little problem co-opting any aspirations for universality into its efforts at cultural imperialism and Cold War struggle.

Ansari focuses on “musical Americanism” as a problematic collective project faced by individual art music composers; Phil Gentry, by contrast, flips the orientation. He starts with individual musical encounters to speak to larger collective problems and concerns, particularly about the question of identity, which he takes to be a crucial area of contestation and change in the decades after World War II. “The central argument of the book,” he explains, “is that the cultural transformation at work here is more fundamentally the project of self-making called ‘identity’.” For Gentry, “it is a project that is at once both psychological and sociological, a process by which an individual knows him or herself in relation to others in a specific historic moment” (5). How, Gentry wonders, did certain musicians wield sound, timbre, tone, harmony, and rhythm—and even, in John Cage’s case, silence—less to forge an overt political movement than to make sense of self and group?

Taking place within the larger framework of the Cold War, the rise of rhythm and blues, the emergence of new types of ethnic music in the popular mainstream, daring avant-garde assertions about counting silence and noise as musical sound, feminist musical challenges to patriarchal structures, the anti-Orientalist appearances of Asian musicians, and assertions of gayness and queerness formed, according to Gentry, the musical dimensions of “a new project of identity” from which what we now call “identity politics” emerged (5). Before there was a cogent form of identarian politics in the United States, in which groups vied for legal or state-recognized inclusion, rights, or power based on who they were culturally or ethnically, music was a medium in which they had to figure out the deeper matter of identity itself.

Gentry’s book is, he himself admits, “more descriptive than prescriptive, focusing on small details of specific individuals rather than grander theories of social behavior,” but it nevertheless achieves some intriguing theoretical and interpretive positions by way of close readings of sound not merely as musical text, but also as performance. Gentry notes that the field of performance studies informs his musicology. Whether on recordings or performed live, Gentry contends, musical performance “choreographs” sound, to use dance historian Susan Leigh Foster’s term.[4] It is in performance that identity got made, then revised, resisted, and challenged, then remade again during the Cold War decades, Gentry believes (24). Most of all, he wants to catch little moments when something strange in musical performance encapsulated a shift in identity formation. For instance, a strange harmonic blend in Sonny Til and the Orioles’ smooth, crooning, choral secularized forms of gospel singing reveals the tense class politics of the Black bourgeoisie in a moment when working-class civil rights militancy was increasing during the 1950s. “Even as their music provided the perfect soundtrack for the black bourgeoisie,” Gentry writes, “the Orioles also tapped into an almost inaudible oppositional sentiment that resonated with the nascent African American youth culture, at least to those who wanted to hear it” (58).

Meanwhile, Doris Day’s performances promulgated a mass cultural whiteness that folded extremes into its all-purpose assimilationist conquest of difference; yet the coming tensions of sex and gender that would erupt in the 1960s with women’s liberation and second-wave feminism lurked in Day’s seemingly All-American girl persona. “Unlike the overwhelmingly smooth sound world of R&B vocal groups such as the Orioles,” Gentry writes, “the white girl singers were pushed into extreme vocal effects, encouraged to sing at the very broadest extremes of their registers, and often placed visually, in marketing, television shows, or movie appearances, to emphasize their comedic abilities.” This was a “specific articulation of whiteness” that sought to evoke a “naturalized authenticity” yet in doing so never resolved underlying questions about “femininity, especially when it came to sexuality” (86). Similarly, in tracking shifting representations of Asia during the Korean War era and its aftermath, with the American involvement in the Vietnam War hovering on the horizon, Gentry again highlights shifting contestations of identity that had lurking political implications. Colonial stereotypes in musicals by Rogers and Hammerstein, he writes, began to give way to new spaces for Asian-made identities at the margins of the often-inhospitable mainstream American milieu (117).

Finally, in a chapter that might have formed a book in of itself, Gentry carefully reconstructs the milieu of early performances of John Cage’s 4’33”. Cage generally resisted identity politics, pushing for what Gentry rather cleverly calls the composer’s “anti-identitarian identification” (136). Nonetheless, he argues that the daring composition of 4’33”, in which music became nothing more than whatever atmospheric noises were in the air at the time, fed a resistance to mainstream American configurations of the heteronormative, conformist self in the postwar decades. To Gentry, a kind of “queer discourse” flourished in the sheer physicality of the performance of 4’33”. The emphasis on the piano as a material object and the experience of bodies together in space unsure of how to make sense of the piece and thereby made more alert to the presence of each other’s awkwardness yet also their individual agencies as actors in the world created a volatile musical space not merely for identity formation, but also for identity reformation (126). “Scenes of mass seduction,” Gentry writes, met Cage, David Tudor, and colleagues as they toured the piece in the early 1950s, such as when the all-male audience in Wesleyan University’s Memorial Hall virtually stormed the stage upon Cage’s invitation that they witness his preparation of the piano. When performed, the composition was, Gentry contends, indicative of the composer’s “oppositionality.” It was not outrightly political, but 4’33” became an opportunity for Cage’s “utopian desire to educate his audiences, to change the way they thought” by fostering a disconcerting setting that was “at once pedagogical and perhaps faintly erotic” (149). Out of silence, noise; out of listening, music; just beyond the conventions of the concert hall, a world of potentially liberating action.

This was, Gentry believes, Cage’s intent with daring composition and it still had an effect decades later, when Gentry heard the piece performed for the first time. He recalled that “for four and a half minutes we contemplated the physical presence of strangers’ breath next to us, strangers willing to also sit quietly and listen to the silence” (150). Here was an experience of ecological sounds to be sure, of a natural world larger than the human one, but it was most of all an experience of other audience members “shuffling, coughing, murmuring, and breathing” (150). The sociality of silence resonated in the room. Identity was not created in this context so much as dismantled. Identity politics gave way to the possibilities of the universal human condition, experienced in moments of togetherness.

Yet by ending his book this way, with a close reading of the radical implications of Cage’s daring piece, Gentry almost undercuts the very arguments of his own study. The focus on self gives way to a yearning for collective connection, the making of identity to its unmaking in communal bonding. That old trickster Cage is up to his usual confoundings. So too, the composer turns up, slyly, in Ansari’s book. When Leonard Bernstein worries that his 1965 composition Chichester Psalms is so tuneful it will be “certain to sicken a stout John Cage,” Ansari is struck that Bernstein desperately yearned to combine Cage’s daring moves with a more palatable sense of musical convention (189). Strike another victory for Cage’s unsettling avant-garde gestures. He out-cooled the Cold War itself, generating new possibilities far beyond its rules, anarchically defying its efforts to order society.

These two books catch some of the tone of the Cold War decades. They remind us that music, if handled skillfully, is an excellent vehicle for investigations of intellectual history. Ansari pays attention to art music caught up in state policy and cultural pressure. What would it take, she asks, for composers to stay in tune with the times? Could they ring the alarm of dissonance and dissent or were they always doomed to reproduce larger structures of power? Addressing this question, she helps us understand the ways in which music responded to, mediated, and sometimes even resisted larger geopolitical forces. Gentry explores how musicians and their fans reached for new tonal centers of identity. Sometimes they even succeeded at altering the very sense of self itself. Both books take note of how musical notes mattered. In doing so, they allow us to hear how music pitched the Cold War world in new directions.

[1] See, for instance, Carol J. Oja, Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[2] See Timothy D. Taylor, Beyond Exoticism: Western Music and the World (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007).

[3] Nadine Hubbs, The Queer Composition of America’s Sound: Gay Modernists, American Music, and National Identity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

[4] See, for instance, Susan Leigh Foster, Choreography & Narrative: Ballet’s Staging of Story and Desire (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998); Choreographing Empathy: Kinesthesia in Performance (New York: Routledge, 2011); and the collection of essays she edited, Choreographing History, ed. Susan Leigh Foster (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995). Her work is just one example of the vast field of Performance Studies, which, as a side note, would be valuable to integrate more extensively into intellectual history.

July 12, 2024

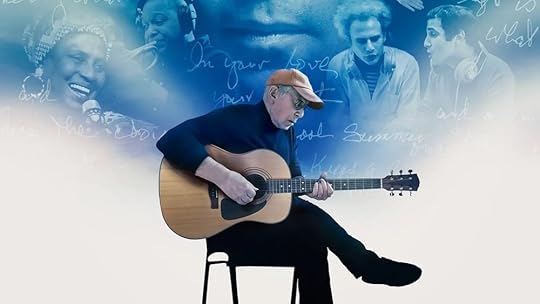

Limning Simon

In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon is, on one level, a simple rock documentary: the creative process is celebrated, the career story unfolds album by album, and we tilt a bit, at times, into Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story territory, with a sort of rise and fall and rise again narrative. Simon’s relationships to friends and lovers—Art Garfunkel, Lorne Michaels, Carrie Fisher, Edie Brickell—float across the surface of the story. Even Simon’s lyrics, which are often wry, witty, funny, heartfelt, wise, and profound, almost evaporate away in the film. To convey their literary beauty, humor, and cleverness, documentary filmmaker Alex Gibney places handwritten versions of them across the screen, but they disappear. Everything dissolves into the mist above a more oceanic element.

Within standard rockumentary fare, below the biographical ups and downs, the relationships gone wrong or made right, and even below Simon’s brilliant wielding of language, is his deeper love affair with sounds themselves. They seem, far more than relationships and even more than words, to be the only things that actually make Simon happy—and even then only passingly, in moments of what he calls “bliss.”

Throughout the film, we watch his puppy dog facial expressions at the world, particularly as he ages. We glimpse his overall sense of what looks to be bemusement, skepticism, dissatisfaction, alienation, almost misanthropy at times. There is a kind of distance to his gaze at the world. Yet it turns into something else when he is engaged with musical creation. Performing with a wide range of musicians or composing his recent spiritual meditation on death, Seven Psalms, in his home studio, some other side of Simon appears. We see something almost like a twinkle in his eye appear when he finds a new way to twist his gentle tenor around one of his fine melodies or when he discovers a fresh chordal harmonic change.

Here, the film suggests overall, is someone who is oddly at one and the same time both open and closed to the world, who receives its many forces, energies, politics, cultural developments in the world, keeping, as he puts it, his finger on the pulse, but also pulling back, alone, highly aware of what he called, in one song, the “myth of the fingerprints.” He has learned to live alone. Yet there is something powerfully social about the only living boy in New York. Like a tuning fork, he channels larger vibrations into musical communiques, transferring the everyday static into something skyward. His own biographical relationships inform this work and the lyrics are a kind of impress of it, a record, a set of stamped observations; but it is, in the end, only the music that gets Simon to another plane. He seeks sounds worthy of existing beyond silence.

July 9, 2024

Dead Heat

I cannot currently locate the citation, but once I recall Beat poet Allen Ginsberg (or was it Michael McClure?) had a vision that the entire world was so full of cars and people that it just stopped in a global traffic jam, frozen. It was a typical Blakean Beat sort of vision, a world of terror and beauty, innocence revealed, fraughtly, in experience, the failures of human sociality and technological innovation rendering a kind of spiritual opportunity to see something else possible from disaster. Most of all, though, this vision strikes me as presaging new dynamics of tempo and time in human living that was just beginning to emerge in the postwar era.

This sense of things speeding up until they clotted up would get picked up as a theme, of course, in many places, such as Don Delillo’s fiction or Mark Fisher’s social criticism or the remarkable Christian Marclay film The Clock.

The world has sped up due to technologies of communication, transportation, computation, integration. Yet in speeding up, the phenomenological experience is, strangely, of a new kind of slowness. The cars are in a traffic jam, but the traffic jam is somehow a kind of slow-motion car crash as well. Rapidity, fastness, vastness of scale produces not just the awesome sublimity of Henry Adams’ dynamo, a new kind of bigness, but also a feeling of torpor and inertia, a new sort of slowness. From climate change to computation, finance to governmental action, entropy and decay rule precisely because consolidation and concentration increase. We no longer have a clear sense of how centralization and decentralization relate to each other. Acceleration, experienced in its current arrangement of intensified automation and connectedness, starts to feel like deceleration. The hare has become a tortoise, the sprinter a laggard. A sort of counterintuitive narcosis of speed has developed in contemporary culture, the feeling that things are moving so fast, circulating so quickly, that we have arrived at a stalemate, or worse yet we sink into a kind of slow rot.

It is an experience of a kind of hurtling listlessness. As the world has sped up, it has quite oddly also slowed down. Scales of motion do not match anymore. Increasingly accessing the cloud, we find our feet stuck in the muck, decreasing in power and thrust. We are out of sync.

The challenge for humans in the twenty-first century, perhaps, is to find our legs in these new tempos of slow and fast combined into a new equation, when the dynamo, pumping harder than ever before, starts to seem like it is in a dead heat.

June 30, 2024

Rovings

Anna Kunz, Tuning The Void, 2024.SoundsArto Lindsay, Encyclopedia of ArtoThe Golden Paliminos, A Dead HorseCaetano Veloso, EstrangeiroCaetano Veloso, CirculadoGal Costa, *O Sorriso do Gato de AliceZeca Pagodinho, *Ao VivoWalter Ruttmann, Weekend, Radio BerlinThe Western Elstons, “Toast That Lie Again”Ellie Armon Azoulay, Diasporic Connections, May 2024Various Artists, Wilderness America: A Celebration Of The LandWordsSam Hillmer, “Arto Lindsay: Space, Parades, and Confrontational Aesthetics,” New Music USA, 1 November 2015Owen Hatherley, “Wild Resistance,” London Review of Books, 25 May 2024Brandon Kreitler, “Doom Scroll: Jorie Graham’s late style,” The Point, 23 May 2024Merve Emre, “The Critic as Friend: The challenge of reading generously,” Yale Review, 10 June 2024Rachel Federman, “America is Waiting: Bruce Conner and the Cultural Zeitgeist,” SFMOMA, October 2016Jennifer Krasinski, “Toshiko Takaezu,” 4Columns, 31 May 2024Nat Segnit, “A scream heard behind the glass: The logical terminus of Rachel Cusk’s journey in selfhood,” TLS, 14 June 2024Taylor Crumpton, “Beyoncé Has Always Been Country,” Time, 14 February 2024Simon Wu, “Party Politics: The Last Days of Queer Club Culture,” The Drift, 24 June 2020Megan Robinson, “The Transformations of Katherine Dunham: The dance pioneer’s contributions to postmodern anthropology,” Public Seminar, 11 June 2024Brad Farberman, “For Gastr del Sol, the Sense of Wonder Remains,” Tidal, 31 May 2024Adam Shatz, “Ever-New Sound Worlds,” New York Review of Books, 21 December 2023Alex Rossen, “Ideology After Marxism.” Public Seminar, 10 June 2024Adam Shatz, “Israel’s Descent,” London Review of Books 46, 12, 20 June 2024John Weber, “The Image of Control: Following the careers of a family of especially corrupt border control officials,” History News Network, 11 June 2024Adam Gopnik, “How the Philosopher Charles Taylor Would Heal the Ills of Modernity,” New Yorker, 17 June 2024Greg Jackson, “Within the Pretense of No Pretense,” The Point, 17 December 2023Terence McGinley, “Archival Treasures ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’,” New York Times, 2 June 2024Selby Wynn Schwartz, “Holding Hands with the Archive: A Conversation with Julian Carter,” Los Angeles Review of Books, 6 June 2024Jennifer New, Drawing from Life: The Journal as ArtRobert W. Cherny, San Francisco Reds: Communists in the Bay Area, 1919–1958Elise A. Mitchell, “Across the Atlantic: Morbidity, Geography, and the Eighteenth-Century French Atlantic Slave Trade.” Atlantic Studies 21, 1 (January 2024): 90–114Ashok Kumar, Robert Knox, et. al., “Race and Capital,” Historical Materialism 31, 2 and 3 (January 2024)Loïc Wacquant, “The Trap of ‘Racial Capitalism.’” European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie 64, 2 (August 2023): 153–62.Barbara Foley, “Intersectionality: A Marxist Critique,” Black Agenda Report, 14 November 2018 (originally published in Monthly Review Online)Tom McGrath, “How 1980s Yuppies Gave Us Donald Trump,” Politico, 4 June 2024Thomas Zimmer, “Fascism in America?,” Democracy Americana, 22 May 2024Thomas Zimmer, “The Anti-Liberal Left Has a Fascism Problem,” Democracy Americana, 24 May 2024Salem Elzway and Jason Resnikoff. “Whence Automation? The History (and Possible Futures) of a Concept,” Labor 21, 1 (March 1, 2024): 27–41Sharon Marcus, “Capitalism Alone Is Not the Problem,” Public Books, 18 October 2023Michael Brenes, “How Liberalism Betrayed the Enlightenment and Lost Its Soul,” Jacobin, 31 May 2024Mehrsa Baradaran, Anne O. Krueger, Mariana Mazzucato, Dani Rodrik, Joseph E. Stiglitz, and Michael R. Strain, “What Comes After Neoliberalism?,” Project Syndicate, 4 June 2024Jennifer Szalai, “Shrink the Economy, Save the World?,” New York Times, 8 June 2024John Banville, “Back to the State of Nature,” New York Review of Books, 21 December 2023Maya Goodfellow, “‘What if there just is no solution?’: How we are all in denial about the climate crisis,” The Guardian, 20 June 2024“Walls”Anna Kunz, Paintings to the Full Flower Moon @ Alexander Berggruen GalleryRay Johnson: Paintings and Collages 1950-66 @ Craig Starr GalleryWorks by Tony Lewis with Bethany Collins, Devin T. Mays & Ellen Rothenberg @ Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, GalleryOpening Passages: Photographers Respond to Chicago and Paris @ Chicago Cultural CenterChason Matthams, Agape in the Spectrum @ Magenta PlainsMonsieur Zohore, Get Well Soon @ Magenta PlainsDan Dowd, Resurface @ Magenta PlainsJake Longstreth, American Heat @ Galerie Max Hetzler BerlinGabriel Lester: Odeon @ Blaffer Art MuseumAmy Sillman, To Be Other-Wise @ Gladstone GalleryBiophilia: Nature Reimagined @ Denver Art MuseumBrittany Marcoux, The Stephen Shore ProjectToshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within @ Noguchi MuseumRichard Diebenkorn: Figures and Faces @ Van Doren WaxterChiura Obata @ SFMoMARagnar Kjartansson: The Visitors @ SFMoMAWhat Matters: A Proposition in Eight Rooms @ SFMoMAAfterimages: Echoes of the 1960s from the Fisher and SFMOMA Collections @ SFMoMAAmerican Beauty: The Osher Collection of American Art @ de Young Museum of Fine ArtsLeilah Babirye: We Have a History @ de Young Museum of Fine ArtsPor el Pueblo: The Legacy & Influence of Malaquías Montoya @ Oakland MuseumBruce Johnson, Form and Energy @ Bruce Johnson StudioEarly Days: Indigenous Art from the McMichael Canadian Art Collection @ Chrysler Museum of Art“Stages”All the Way Around and Back, Charlies Ives Society Roundtable @ Charles Ives Society Online, 17 June 2024International Contemporary Ensemble and PRiSM: Music, AI, and Co-creation @ Roulette, 16 May 2024Weston Olencki + TAK Ensemble @ Roulette, 21 May 2024Arto Lindsay Talks Brazilian roots, DNA, and drum & bass @ Red Bull Music Academy, 1 August 2017Arto Lindsay: The Penny Parade in Berlin @ Unter den Linden to the Brandenburg Gate and ended at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 11 October 2009Mirandra Fricker, “Bernard Williams’ Historical Self-Consciousness” @ 2024 Whitehead Lecture One, Harvard University, 14 May 2024Jake Longstreth @ Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 8 February 2024Cathy Cohen and Lisa Wedeen, speakers Anton Ford, Gabriel Lear, and Gina E. Miranda Samuels, “On University Values,” @ University of Chicago Center for Contemporary Theory, 30 April 2024No Man’s Land @ National Theatre of England, December 2016The House of Bernarda Alba @ National Theater of England, November 2023Merry Wives of Windsor @ Public Theater, 13 June 2024Ursula Eagly, Dream Body Body Building @ Chocolate Factory Theater, 6 March 2024Wanjiru Kamuyu, A disguised welcome… @ Chocolate Factory Theater, 22 September 2023Takahiro Yamamoto, NOTHINGBEING @ Chocolate Factory Theater, 6 October 2023Michelle Ellsworth, Evidence of Labor and the Post-Verbal Social Network @ Chocolate Factory Theater, 9-11 November 2023Government Song Woman: Sidney Robertson, Folk Music Collecting, and FDR’s New Deal @ Kluge Center Library of Congress, 26 June 2024ScreensAmbitious Lovers, “Copy Me” and “Admit It,” Night Music, 1989

Disco: Soundtrack of a Revolution

Marta Renzi, You Little Wild HeartPhil Buehler and Steve Siegel, “A Film from 1974 Offers a Rare Glimpse Inside an Abandoned Ellis Island,” New York Times, 28 May 2024Stan Brakhage, The Wonder RingMonsieur Spade

Anna Kunz, Tuning The Void, 2024.SoundsArto Lindsay, Encyclopedia of ArtoThe Golden Paliminos, A Dead HorseCaetano Veloso, EstrangeiroCaetano Veloso, CirculadoGal Costa, *O Sorriso do Gato de AliceZeca Pagodinho, *Ao VivoWalter Ruttmann, Weekend, Radio BerlinThe Western Elstons, “Toast That Lie Again”Ellie Armon Azoulay, Diasporic Connections, May 2024Various Artists, Wilderness America: A Celebration Of The LandWordsSam Hillmer, “Arto Lindsay: Space, Parades, and Confrontational Aesthetics,” New Music USA, 1 November 2015Owen Hatherley, “Wild Resistance,” London Review of Books, 25 May 2024Brandon Kreitler, “Doom Scroll: Jorie Graham’s late style,” The Point, 23 May 2024Merve Emre, “The Critic as Friend: The challenge of reading generously,” Yale Review, 10 June 2024Rachel Federman, “America is Waiting: Bruce Conner and the Cultural Zeitgeist,” SFMOMA, October 2016Jennifer Krasinski, “Toshiko Takaezu,” 4Columns, 31 May 2024Nat Segnit, “A scream heard behind the glass: The logical terminus of Rachel Cusk’s journey in selfhood,” TLS, 14 June 2024Taylor Crumpton, “Beyoncé Has Always Been Country,” Time, 14 February 2024Simon Wu, “Party Politics: The Last Days of Queer Club Culture,” The Drift, 24 June 2020Megan Robinson, “The Transformations of Katherine Dunham: The dance pioneer’s contributions to postmodern anthropology,” Public Seminar, 11 June 2024Brad Farberman, “For Gastr del Sol, the Sense of Wonder Remains,” Tidal, 31 May 2024Adam Shatz, “Ever-New Sound Worlds,” New York Review of Books, 21 December 2023Alex Rossen, “Ideology After Marxism.” Public Seminar, 10 June 2024Adam Shatz, “Israel’s Descent,” London Review of Books 46, 12, 20 June 2024John Weber, “The Image of Control: Following the careers of a family of especially corrupt border control officials,” History News Network, 11 June 2024Adam Gopnik, “How the Philosopher Charles Taylor Would Heal the Ills of Modernity,” New Yorker, 17 June 2024Greg Jackson, “Within the Pretense of No Pretense,” The Point, 17 December 2023Terence McGinley, “Archival Treasures ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’,” New York Times, 2 June 2024Selby Wynn Schwartz, “Holding Hands with the Archive: A Conversation with Julian Carter,” Los Angeles Review of Books, 6 June 2024Jennifer New, Drawing from Life: The Journal as ArtRobert W. Cherny, San Francisco Reds: Communists in the Bay Area, 1919–1958Elise A. Mitchell, “Across the Atlantic: Morbidity, Geography, and the Eighteenth-Century French Atlantic Slave Trade.” Atlantic Studies 21, 1 (January 2024): 90–114Ashok Kumar, Robert Knox, et. al., “Race and Capital,” Historical Materialism 31, 2 and 3 (January 2024)Loïc Wacquant, “The Trap of ‘Racial Capitalism.’” European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie 64, 2 (August 2023): 153–62.Barbara Foley, “Intersectionality: A Marxist Critique,” Black Agenda Report, 14 November 2018 (originally published in Monthly Review Online)Tom McGrath, “How 1980s Yuppies Gave Us Donald Trump,” Politico, 4 June 2024Thomas Zimmer, “Fascism in America?,” Democracy Americana, 22 May 2024Thomas Zimmer, “The Anti-Liberal Left Has a Fascism Problem,” Democracy Americana, 24 May 2024Salem Elzway and Jason Resnikoff. “Whence Automation? The History (and Possible Futures) of a Concept,” Labor 21, 1 (March 1, 2024): 27–41Sharon Marcus, “Capitalism Alone Is Not the Problem,” Public Books, 18 October 2023Michael Brenes, “How Liberalism Betrayed the Enlightenment and Lost Its Soul,” Jacobin, 31 May 2024Mehrsa Baradaran, Anne O. Krueger, Mariana Mazzucato, Dani Rodrik, Joseph E. Stiglitz, and Michael R. Strain, “What Comes After Neoliberalism?,” Project Syndicate, 4 June 2024Jennifer Szalai, “Shrink the Economy, Save the World?,” New York Times, 8 June 2024John Banville, “Back to the State of Nature,” New York Review of Books, 21 December 2023Maya Goodfellow, “‘What if there just is no solution?’: How we are all in denial about the climate crisis,” The Guardian, 20 June 2024“Walls”Anna Kunz, Paintings to the Full Flower Moon @ Alexander Berggruen GalleryRay Johnson: Paintings and Collages 1950-66 @ Craig Starr GalleryWorks by Tony Lewis with Bethany Collins, Devin T. Mays & Ellen Rothenberg @ Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, GalleryOpening Passages: Photographers Respond to Chicago and Paris @ Chicago Cultural CenterChason Matthams, Agape in the Spectrum @ Magenta PlainsMonsieur Zohore, Get Well Soon @ Magenta PlainsDan Dowd, Resurface @ Magenta PlainsJake Longstreth, American Heat @ Galerie Max Hetzler BerlinGabriel Lester: Odeon @ Blaffer Art MuseumAmy Sillman, To Be Other-Wise @ Gladstone GalleryBiophilia: Nature Reimagined @ Denver Art MuseumBrittany Marcoux, The Stephen Shore ProjectToshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within @ Noguchi MuseumRichard Diebenkorn: Figures and Faces @ Van Doren WaxterChiura Obata @ SFMoMARagnar Kjartansson: The Visitors @ SFMoMAWhat Matters: A Proposition in Eight Rooms @ SFMoMAAfterimages: Echoes of the 1960s from the Fisher and SFMOMA Collections @ SFMoMAAmerican Beauty: The Osher Collection of American Art @ de Young Museum of Fine ArtsLeilah Babirye: We Have a History @ de Young Museum of Fine ArtsPor el Pueblo: The Legacy & Influence of Malaquías Montoya @ Oakland MuseumBruce Johnson, Form and Energy @ Bruce Johnson StudioEarly Days: Indigenous Art from the McMichael Canadian Art Collection @ Chrysler Museum of Art“Stages”All the Way Around and Back, Charlies Ives Society Roundtable @ Charles Ives Society Online, 17 June 2024International Contemporary Ensemble and PRiSM: Music, AI, and Co-creation @ Roulette, 16 May 2024Weston Olencki + TAK Ensemble @ Roulette, 21 May 2024Arto Lindsay Talks Brazilian roots, DNA, and drum & bass @ Red Bull Music Academy, 1 August 2017Arto Lindsay: The Penny Parade in Berlin @ Unter den Linden to the Brandenburg Gate and ended at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 11 October 2009Mirandra Fricker, “Bernard Williams’ Historical Self-Consciousness” @ 2024 Whitehead Lecture One, Harvard University, 14 May 2024Jake Longstreth @ Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 8 February 2024Cathy Cohen and Lisa Wedeen, speakers Anton Ford, Gabriel Lear, and Gina E. Miranda Samuels, “On University Values,” @ University of Chicago Center for Contemporary Theory, 30 April 2024No Man’s Land @ National Theatre of England, December 2016The House of Bernarda Alba @ National Theater of England, November 2023Merry Wives of Windsor @ Public Theater, 13 June 2024Ursula Eagly, Dream Body Body Building @ Chocolate Factory Theater, 6 March 2024Wanjiru Kamuyu, A disguised welcome… @ Chocolate Factory Theater, 22 September 2023Takahiro Yamamoto, NOTHINGBEING @ Chocolate Factory Theater, 6 October 2023Michelle Ellsworth, Evidence of Labor and the Post-Verbal Social Network @ Chocolate Factory Theater, 9-11 November 2023Government Song Woman: Sidney Robertson, Folk Music Collecting, and FDR’s New Deal @ Kluge Center Library of Congress, 26 June 2024ScreensAmbitious Lovers, “Copy Me” and “Admit It,” Night Music, 1989

Disco: Soundtrack of a Revolution

Marta Renzi, You Little Wild HeartPhil Buehler and Steve Siegel, “A Film from 1974 Offers a Rare Glimpse Inside an Abandoned Ellis Island,” New York Times, 28 May 2024Stan Brakhage, The Wonder RingMonsieur Spade

June 13, 2024

Vessels

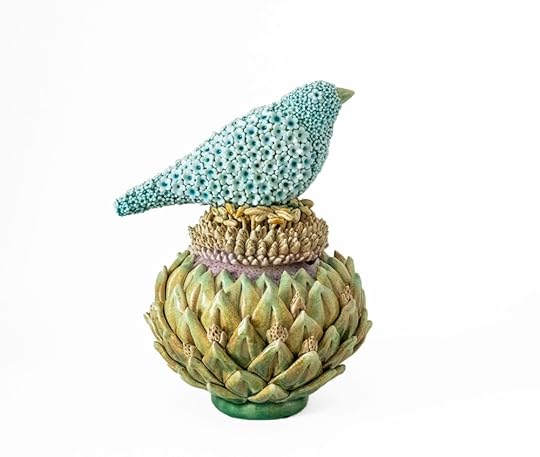

Kate Malone, Small Lidded Flower Jar and Waddesdon Bird, 2016.

Kate Malone, Small Lidded Flower Jar and Waddesdon Bird, 2016.The pots, urns, mugs, and vases in the Victoria Schonfeld Collection and the Radical Clay exhibitions long to be more than vessels. They want to be the thing itself, not the container for the thing. They bend, turn, gyrate, twist, laugh, scream, wilt, gesture, almost seem to break. They dance. Sometimes they seem to hold something inside that they refuse to show you. Other times, they reveal their most interior dimensions. Some are silent. Some give you lip. Some are cold and stony. Others seem full of hot air, preening for your eyes. They mug for the viewers eye. Some feel like they want to protect. Others seem to want to bump into you, to break out from their brittle, fired, frozen state. Some accost you aggressively, while others feel like they are running away from your gaze. Some are gentle and nurturing, others are violent and extreme. Some are interested in your eyes, maybe even in your touch. Others glaze over at the thought of human interest.

Do these objects have genders? Not really, but like all sculpture, sometimes they feel like they want to mess with the relationship between body and identity, between hands and dirt, between the cultural and the biological.

Tanaka Yu, Bag Work, 2018.

Tanaka Yu, Bag Work, 2018.My favorite moment in these exhibits of ceramic glory is Steve Tobin’s video, Bang, in which he uses firecrackers to pop, blow up, and shape clay. These are the sounds of something soft but sturdy surviving, something beautiful emerging from explosive heat, something capable of capturing the pressures of the world without melting away. It is a video about creation, edited in a sonic and visual rhythm of fast and slow motion to reveal the meeting of elements to create motion from stillness, the impact of air on earth.

Myashita Zenji Triangular, 2003.

Myashita Zenji Triangular, 2003.In the end, what are any of us but vessels, fragile holders of ideas, not so much forged like steel as cooked in kilns, shaped by our worlds, capable of containing multitudes, eventually cracking up into shards? Ashes to ashes, clay to clay—but first, there are stances to take, poses to critique, things to carry.

Mishima Kimiyo, Untitled (Crushed Asahi Beer Box), 2007.

Mishima Kimiyo, Untitled (Crushed Asahi Beer Box), 2007.June 11, 2024

Pincers

Flying into LaGuardia Airport last year, the plane flew right over Manhattan. Two of the so-called “pencil towers” on Billionaire’s Row looked like nothing less than a pair of tweezer-like pincers squeezing the life out of Central Park.

For more on these buildings and their troubling story, see Karrie Jacobs’ excellent essay, “Elevators and Escalades,” The Nation, 10 June 2024.

June 10, 2024

Revolutions That Weren’t?

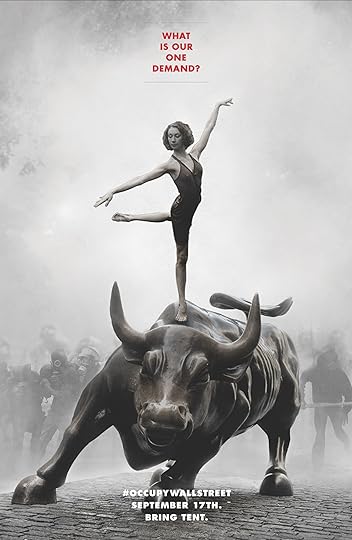

Occupy Wall Street poster by Will Brown for Adbusters, 2011.

Occupy Wall Street poster by Will Brown for Adbusters, 2011.Freedom isn’t free / No, there’s a hefty f-ckn’ fee.

— Team America World Police, written by Trey Parker

While flourishes of radical agitation such as the protests against the Israeli war in Gaza continue to appear of late, authoritarianism is on the rise in the 2020s. We certainly seem, perhaps, to be in a new historical moment. The geopolitical influence of the United States is waning. Climate change intensifies. The Covid-19 pandemic still affects contemporary life. There remains the feeling of stalemate everywhere, but the stalemate itself, which at first suggests a stubborn continuity, which is to say a lack of change, might oddly itself be the engine of historical change. Lenin famously remarked, “There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen,” but in the twenty-first century, it’s hard to tell on what timeline we move, exactly.

As the 2020s unfold, the slow-motion spin of events has got me thinking about the explosion of protest that took place from the early 2000s through the middle of the 2010s. How might we begin to understand the Color Revolutions, Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, the Black Lives Matter movement, and other outbreaks of agitation from the first decades of the twenty-first century? What was this worldwide outbreak of popular protest? It was left-wing, to be sure, but just as often it was amorphously ideological. One might even include more reactionary popular protests within it: the Tea Party Movement, the Yellow Vests Protests, the Movimento Vem pra Rua in Brazil.

These movements were all influenced by a palpable frustration with neoliberal policies that sacrificed everyday people’s lives for the profits of the global finance sector, yet they were almost all shaped by new technologies of social media that arose within the neoliberal global arrangement. With their algorithmic capacities to amplify voices from below and foster communities beyond official channels, social media platforms seemed revolutionary, yet they were almost all co-opted, if they were ever anything more than commercial forms within neoliberalism in the first place. Their intent was always to sell advertising by intensifying controversy and extremism. Fairly quickly, they were appropriated by state power to spread disinformation systematically. They even quickly shifted from extremism to exterminationism, as in the ways Facebook sparked genocide in the Rohingya massacres in Myanmar. Overall, both the social movements—at least the grassroots ones on the left—and the technologies that they harnessed to try to organize themselves seemed to exhaust themselves. If they did not fragment, they flowed one click and one like after another right back into the very forces they sought to oppose, resist, or perhaps overthrow.

Almost all the social uprisings of the early 2000s could also be said to have taken shape within the US War on Terror. Here an intriguing possibility for further investigation appears: how did the War on Terror’s emphasis on spreading, if by paradoxical force, freedom, openness, and democracy relate to the social protests of the time period? The War on Terror found neoconservatives in the United States able to incorporate centrist-liberal (neoliberal) and isolationist right-wing elements into a militarized and political assertion of the idea that one could enforce new forms of democracy and impose new types of freedom on peoples around the world. Antiterrorism and counter-insurgency, the neoconservative project claimed, would generate liberal democracy. If Francis Fukuyama’s famous “end of history” thesis after the conclusion of the Cold War did not prove true by 9/11, then neoconservatives would make it so: liberal democracy would flourish at the point of a gun (eventually at the bottom of a drone).

It proved to be an odd and tragic endeavor, parodied most effectively by the absurdist, sardonic 2004 film Team America: World Police, written by the makers of the television cartoon series South Park. One might think of this film as the early-2000s Dr. Strangelove. “Freedom isn’t free,” a group of surreal American freedom fighter puppets sing, pausing for a montage of patriotic reflection before returning to blowing things up and killing people around the world, “No, there’s a hefty f-ckin’ fee/ And if you don’t throw in your buck ‘o five / Who will?”

This intense interest in freedom is what, we might hypothesize, tied together the War on Terror and the various leftwing social movements and protests that arose within its defining imperial stretching around the world after 9/11. Radical movements sought out the possibilities of freedom. In doing so, they took decidedly anarchistic turns in their politics, partly in reaction to the failures of socialism and communism in the twentieth century and partly because freedom was the hinge upon which the confluence of neoliberalism and neoconservatism turned.

While the early twenty-first century protest movements were most certainly and seriously engaged with anarchistic political theories, concepts, and tactics, as the uprisings played out in the streets they typically became less concerned with clear programs of change or concrete calls for reform, even anarchistic ones. Instead, they leaned into the production of momentary feelings of freedom, openness, and possibility. Syndicalism as strategy gave way to the fleeting satisfactions of spontaneity. Improvisation’s potential gave way to impossible demands. This is something the film documentarian Adam Curtis noticed with chilling but incisive awareness in his film All Watched Over By Machines of Living Grace), a study of the lurking libertarianism found within the combination of ecology and technology that gave rise to the influential Californian Ideology.

The feeling of freedom, of throwing off some kind of constraint, linked the many diverse protest movements of the early twenty-first century. They all displayed more an urge to discover ends in the means rather than develop means for an end. Occupy Wall Street was indicative of this larger sensibility, with its refusal to put forward demands and its effort at prefigurative politics, but so too were the Color Revolutions and even, to a lesser extent, Arab Spring.

It would seem that the “multitude,” heroes of 1990s and early 2000s political theory and cultural studies (see Negri and Hardt’s Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire) could reach for freedom, but then what? When met, inevitably, with backlash and repression, they fragmented or dissipated. Meanwhile, democracy stood in the balance, an elusive goal that was not quite the same as freedom, but somehow became enfolded within the giant, hopeful, troubling, still unfinished mess of early twenty-first century unrest.