Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 5

January 27, 2025

Love In

To the music of D’Angelo, Kyle Abraham’s dance company, A.I.M. focused on the loving side of Black American life. The set featured a domestic vibe, a comfy couch, a few plants, and not much else as the dancers moved through different roles—many about flirting, playing, teasing, supporting, relating, admiring, showing off a bit, and, most of all, finding a few safe spaces within the music’s grooves for living fully in oneself and exchanging, concealed by the thump and the cries of the soundtrack, admiration and appreciation. The ensemble was, as a few members and Abraham himself put it, focused on “loving on one another.”

The larger woes of an anti-Black world occasionally edged in on the love in. A recorded commentary lifted from the basketball coach Doc Rivers, who famously commented on the shooting in the back of Jacob Blake, 29, by police in Kenosha, Wisconsin echoed out at one point. Mostly, however, the focus was on life wrapped up in music, protected by the broader society.

What was most beautiful was the restraint, with occasional explosions of the true virtuosity and power of the dancers. Abraham’s bodily vocabulary has often tended in this direction: a kind of casual lurch or lean or leap pushes suddenly into a powerful moment of movement, perhaps a series of balletic spins, or a difficult Cunninghamian balancing act. The dancers would do this one by one, or occasionally slipping into little trios and quartets.

The most amazing one involved a long slow-motion dance party early on in the work, which was about an hour long in total. Here the dancers played with control and almost-stillness, as if wanting them and us to relish the moment of pleasure, of fun, as if to suggest that in the restraint of the slo-mo was a way to sustain the break, to dance into it, and maybe linger there awhile, away from the sped-up harness and onslaught.

Dancers talked and interacted. There were dates and relationships, comfort food and some gentle teasing. The work ended with a beautiful “assisted solo,” as Abraham called it, hinting at the glints of pain at the margins, but at the center of this work was pure tenderness intersecting with a mighty power: a love supreme.

Working in the safe spaces between the beats, not so much the lower frequencies as the gaps of the oscillations, Kyle Abraham and company reminded us that love needs no title—and that all are entitled to it.

A Fast One

Donald Trump serves you fries at a McDonald’s in Feasterville, Pennsylvania, 20 October 2024. Photo: Doug Mills—The New York Times via AP.

Donald Trump serves you fries at a McDonald’s in Feasterville, Pennsylvania, 20 October 2024. Photo: Doug Mills—The New York Times via AP.Wasn’t that a strange place to do a news conference?

—Donald Trump

Was the clincher for Donald Trump’s presidential campaign of 2024 not the image of him raising his fist after being grazed by a bullet in an assassination attempt in Butler, Pennsylvania, but rather serving fries to the viewer at a McDonald’s down the pike in Feasterville? If this was so, it was not because Americans identified with him as a fellow worker, but rather because he was serving them. The iconic image featured Trump presenting the fries to the viewer, working for them not alongside them.

Herein seemed to be a core error of the Harris campaign: they were trying to galvanize American working class as workers; Trump focused almost exclusively on them as consumers. Recall that Kamala Harris emphasized that she had once worked at McDonald’s, and struggled with the monotony, exploitation, and challenges of low-wage labor in corporatized America. Her emphasis on her similarity to workers seemed to ring false, or at least fall flat. Why?

Perhaps because since Bill Clinton in the 1990s, the Democratic Party has largely treated working Americans not as workers, but as consumers. This was fundamental to the neoliberal turn. We’ll hollow out your industrial life, the Democrats argued, but in turn we’ll flood your Walmarts with cheap goods from China so that you can buy things and feel that you are on the up and up. For thirty years, the Democratic Party has, both symbolically and in terms of policy, treated American workers not as producers, but as buyers. No wonder Trump’s fries tantalized them in a way Harris’s message of worker solidarity did not.

The Democrats thought that they could switch to a worker-based message like that, but they were proved wrong. Responding to challenges from Bernie Sanders and the left as well as the pandemic’s heightened awareness about “essential workers,” the Biden administration pivoted after 2020 to a pro-worker orientation. Neoliberalism was out and a new pro-labor policy and attitude (a stronger NLRB, Biden joining the UAW picket line) was in.

At the same time, the Biden administration crafted economic policy that persisted, in a contradictory manner, in undermining the lives of workers in the full, consumerist mode they themselves had mapped out as the only way forward during the previous thirty years. Biden’s team made a calculation that by heating up the aggregate economy through government spending, but risking inflation (which indeed arrived just as expected) they could prevent a Covid recession. It seemed for a time that the federal government would rise to the occasion to help Americans manage the crisis. It certainly communicated that the Biden administration would help Wall Street avoid a meltdown of the US economy as a whole. This worked compared to other nations at the aggregate level.

However, inflation hit lower-wage workers hard. It did so not in their roles as laborers, but in their identities as consumers. The middle and upper classes could weather inflation, but those who were at the edge of making it could not handle rising prices for basic goods such as gas, milk, meat, and the like. Investing government spending in their lives as workers, the Biden administration destroyed their chances as consumers. Having heated up the economy and offering vague promises of employment in coming years as America “built back better” (mostly experienced by everyday Americans as more construction on their streets and highways rather than help!), the Biden administration then abandoned this investment. They tried to cool inflation by raising interest rates and leaving off with Covid-era public funding. And whom did that hurt most of all? The same working class they claimed to help, again in their role as buyers, this time in their consuming hopes to be home owners as mortgages rose in cost. Inflation went down, but so too did the option of purchasing a home.

In short, the Biden administration portrayed itself as the party of American workers, but the workers said, we aren’t workers, we are consumers. You told us that was our identity for decades. Why would we change that orientation now.

Harris largely continued this approach. I’m a McDonald’s worker too, she proposed in her campaign (she did actually work at McDonald’s at one point despite Trump, as usual, claiming that she was lying in typical post-truth fashion). And to her, American workers responded: nah, lady. They turned to Trump and smiled. Serve up the fries, boss.

Once the Republican Party renamed them “freedom fries” in the buildup to the Iraq War, when the French wouldn’t go along with the lying propaganda campaign about “weapons of mass destruction.” Now, Trump seized the fries to claim the role of providing consumer satisfaction. It wasn’t about who had grease on their knuckles in the past, it was about the visual fantasy of an upside-down world in which a worker was served up potatoes by the liege lord. That’s what Donald Trump tapped into with his image: a man in a suit wearing a brown McDonald’s apron, standing for a moment next to a man who had worked there for eight years. He was not sharing the role of laborer with the young worker, but of boss pretending to work the line with him. He hit the young man showing him how to work the machine aggressively on the shoulder, as if to suggest not I’m with you, but I’ll fire you if you don’t smile for the camera with me. It was The Apprentice all over again, only saltier. These are for you, he said to the viewer behind the camera lens. These are for you, he said to the handpicked people who pulled up to the take-out window for the publicity stunt. These are for us, he proposed.

Fast food helped Trump pull a fast one. As Helen Rosner pointed out in a 2019 New Yorker article:

Trump’s affinity for fast food has been well documented since the earliest days of his public life. In the nineties and early two-thousands, he filmed commercials for Pizza Hut and McDonald’s. On the campaign trail, at a televised CNN town hall, he explained to Anderson Cooper that he enjoyed “a fish delight,” referring to the Filet-o-Fish. He continued, “The Big Macs are great. The Quarter Pounder. It’s great stuff.” Trump seemed to relish posing with fast food, especially the winking high-low of Instagram photos of himself eating value meals on his private plane: here’s Donald Trump grinning with a bucket of K.F.C., there’s Donald Trump grinning with a Big Mac and a cardboard sleeve of fries.

Trump offers working-class Americans a dazzling, magical mix of grandiosity and debasement. I can bring this crap into the highest places of political power, he proposes, the White House, Air Force One. These are no more fancy than the McDonald’s drive-thru booth. You belong here, is the message. And yet you don’t and you never will. If one watches the video of Trump’s visit to Feasterville (you can’t make these names up if you tried), he continually ribs the young man showing him how to work the fryer, suggesting that he better be careful what he says about whether he likes his job since his boss is right there, off camera. This is the boss’s boss talking, in other words, and don’t forget it.

What is on display in the image is not the fantasy, really, that Trump is like you, or you can be like him, but rather that you will never be him or those like him, but he will spend a few minutes shoving some fries in your face. A cornucopia awaits, but always remember that you are lucky to get even a temporary taste.

In a sense, the Democrats have been saying the same thing to the American worker since the 1990s. Neoliberalism denigrated labor and celebrated consumer recuperation for that immiseration and insult. When they tried to switch to a different—in some sense an older—vision of a producerist identity rather than a consumerist one, it did not translate. Offer the short-term pleasure of the Happy Meal for years over the long-term stability of industrial employment and don’t expect people to reject it suddenly for something more solid and lasting.

Consumed by Trump’s appeal to their consumer identities, knowing well that their employment opportunities are grim, gig-like, exploited, and getting worse, Americans in the lower levels of the economic system took the fries and drove off. The Democratic Party will have to work a lot harder to shift what they have created.

January 19, 2025

Putting the Culture in the Counterculture

X-posted from the Society for US Intellectual History Book Review.

Most studies of the 1960s counterculture focus more on the “counter” than the culture. They want to know what did—or did not—make the phenomenon oppositional to the dominant structures of power in American and global life. What were the politics of the counterculture’s strange effort to reimagine, and even possibly revolutionize, both self and society through experimentation with hallucinogenic drugs, a freer sense of sexuality, ecstatic experience, unconventional spirituality, and new configurations of kinship, family, and social relations?[1] Others point to something more like a store “counter” in the counterculture. They concentrate on how institutions of corporate capitalism cleverly diverted dissent into expressive style, channeling rebellion against the system back into the system itself. Counterculturalists may have thought they could have their acid and eat it too, or, later in the twentieth century, as they came of age and became what David Brooks called “bobos in paradise,” that they could have their organic wellness and think they were changing the world too, but all they were doing, in fact, was forming a new market segment of hipness within the existing economic order.[2] There was not much revolution in that.

For art historian Thomas Crow, these two perspectives, which treat the counterculture as either a straightforward social movement or, alternatively, a devious economic legerdemain, pay too much attention to the first half of the term. Which is to say, they tell us a lot about the counter, but not enough about the culture. He believes that if we turn to high art (pun intended), we can begin to better understand the content of the counterculture, which social critic Theodore Roszak first named in 1968 after borrowing the two-word term “counter culture” from sociologists of 1950s juvenile delinquency.[3] Crow wants to know what the actual culture of the counterculture was as well as who created it and what they were up to in doing so. While many assume that the counterculture was “LSD-consuming, motley-garbed, guitar-bashing wastrels” who “could never have had significant bearing on the serious enterprise of advanced visual art” (4), Crow notices a largely submerged world of more fierce and fascinating activity in avant-garde artmaking. Beyond the “rainbow-hued accoutrements of the counterculture in its flamboyant hippie phase” there was a less sunny, but more profound underground culture (3).

The artist Bruce Conner, in particular, becomes a talisman for Crow. When Conner died in 2008, one of his acquaintances, the poet Daniel Abdal-Hayy Moore, memorialized the artist as giving “the so-called ‘counter-culture’ its, well…culture” (7).[4] Tracking Conner’s “restless appetite for adventure and his impatience with boundaries” (35), as well as the daring artwork of fellow travelers such as Wallace Berman, Wally Hedrick, Jay DeFeo, Michael Heizer, Robert Smithson, David Hammons, Corita Kent, Martha Rosler, Rupert García, Senga Nengudi, Chris Burden, and Mike Kelley, Crow contends that behind the “retrospective fascination with the gaudier displays by 1960s free spirits” was a serious and gritty aesthetic and ethical engagement with two key factors: the nature of the self beyond normative definitions of it and a persistent rejection of militarized, Cold War American imperialism (3).

Conner is the main subject of the first five of the twelve chapters in The Artist in the Counterculture. From the late 1950s, when he arrived in San Francisco from Wichita, Kansas, to his fervent documentation of the 1970s punk scene in that City by the Bay and into the twenty-first century, Conner often refused the spotlight, at one point assigning authorship of his work to various other Bruce Conners he found in the phonebook. Here was an effort to deconstruct the self, to question assumptions about coherent, independent individualism in an America mostly focused on constituting it as the end goal of the society. In what Crow wants us to understand as a bold countercultural move, Bruce Conner mystified who Bruce Conner was, refusing to become a commodified brand, even as a symbol of individual rebelliousness (of course, in doing so, one could argue, that is exactly what Conner became, ultimately).

The suspicion of a stable self was not merely an anticommercial move. It was also, Crow argues, fundamentally linked to Conner’s fear of being conscripted into the US military. By way of the draft, the problematic nature of US foreign policy during the Cold War connected directly to questions of individual autonomy and dissolution. Out of this entwining of world and self, the counterculture’s culture began to take shape. For instance, when Conner showed up in San Francisco in the late 1950s at the apartment of his Kansas compatriot Michael McClure, who was at the time forging his own Beat poet career, Conner was disheveled in appearance, looking himself much like the set of dirty, canvas-covered, rusty-nailed, rope-twisted, feathered, stretched nylon, mangled paintings he was in the process of creating. Called The Rat Bastard series, these featured “found” photographs of cadavers or recreations of ancient forms of torture, among other disturbing elements.

Along with other sculptures and paintings such as Child (1959), Temptation of St. Barney Google (1959), Black Dahlia (1960), The Bridge (1960), Crucifixion (1960), Resurrection (1960), Partition (1962), Senorita (1962), Suitcase (1962), and Couch (1963), The Rat Bastard series out-junked the junky assemblages of New York stalwarts such as Robert Rauschenberg. They were not happy or light or easy or playful. Instead, they wanted to present the self as abject and broken, tarnished and suffering, but also open to a bold, authentic confrontation with the difficulties, stresses, and strains of the world. In making these dramatic pieces, Crow argues, Conner connected the two crucial aspects of the counterculture that the art historian recognizes at the core of its aesthetics and ethics: the urge to dismantle conventions of the self and a rejection of the post-World War II military-industrial complex.

Even in the interregnum between the Korean and the Vietnam Wars, during the later years of the Eisenhower administration at the end of the 1950s, Conner found the possibility of being forced into the American Armed Forces intolerable. His art conveyed an abjection of the self under pressure from the larger geopolitical context. As Crow writes, The Rat Bastard series reflects how, for Conner, getting drafted was “deemed by him a force inimical to his personal survival.” Therefore, “he resorted to the artificial cultivation of extreme states of mind and body, self-transformation projected onto an uncomprehending world with extravagant outward dramatics: key traits in any definition of the counterculture” (16).

Conner’s artworks were also about experimentation with drugs such as peyote and, later, LSD. These were not for partying, however, in any simplistic sense of the term. They were methods of investigating the self within Cold War American empire. Drugs inspired a mode of countercultural artmaking that has been mistaken for seeking states of innocence and utopian naïveté. That was, and remains, the hippie cliché. For Conner, by contrast, they were about grappling with fragility and danger. As Conner put it about a sculpture, Snore, made in 1960 after a particularly fraught peyote vision: “I experienced myself as this very tenuously held-together construction—the tendons and muscles and organs loosely hanging around inside—and it seemed like at any moment disaster could strike and you could fall apart. I mean, you were just held together by this thin skin and strings of flesh” (24). The self, for Conner, was not imprisoned by social conventions, it itself was a construction, a social convention, and one always under attack.

No wonder the artist also selected references to Old World masterpieces such as Matthias Grünewald’s Temptation of Saint Anthony (1512–16). Not only did it portray a moment of the self in agony, using the same sort of dense, monstrous, almost overwhelming piles of details that Conner worked into his sculptures and paintings, but additionally, this particular painting, Crow notes, resided in a monastery hospital in the Franco-German Alsace that was famous for treating “St Anthony’s Fire,” the gangrene that came from ingesting the very same ergot fungus on grain that “would yield the refined hallucinogen LSD, lysergic acid being the molecular core of ergot” (22). Drugs were not merely ecstatic releases to peaceful, euphoric freedom. In the culture of the counterculture that Crow wants us to notice, they were also tools for perceiving a self in trouble. This trouble was not only personal, it was public and political. Who else, after all, used LSD in the 1960s to test out ways of destroying and destablizing the self: the Central Intelligence Agency! A suffering self and a Cold War gone mad: the counterculture in this book is far less a utopian, Woodstockian Garden of Eden; it is much more a dystopian Dr. Strangelove black comedy.

Conner not only spent time living in the Haight Ashbury neighborhood long before it became ground zero for the Summer of Love in 1967 and he not only resided close by important San Francisco artists such as his fellow Kansan Michael McClure and painters such as Jay DeFeo, about whose monumental painting/sculpture of going mad, The Rose, he made a powerful film, The White Rose (1967), but he also worked in a studio next to where the important street theater group the San Francisco Mime Troupe rehearsed. In short, look to origins of the counterculture in Northern California, and one almost always finds Bruce Conner not far from the center of the scene (like Crow, artist Ami Magill once made this point to me in an oral history interview[5]). Additionally, Conner made his way to Mexico as well as Boston, where he influenced LSD guru Timothy Leary while resisting both Leary’s huckster opportunism and the cultish bullying of the creepy Mel Lyman. Conner also spent time in Los Angeles, where in his mysterious but charismatic way, he exerted an influence on another of the Kansas City-to-California bohemia set, the actor and director Dennis Hopper.

Not only had Conner started creating his sculptures and paintings by the 1960s, he also took up the mantle of another key artistic format of the era, experimental filmmaking, through engagement with figures such as Harry Smith and Stan Brakhage. In pioneering works of avant-garde film such as A Movie (1958), Cosmic Ray (1962), Breakaway (1966), and Report (1967) Conner used “found” footage to splice together startling proto-music videos about hallucinogenic trips, dancers (featuring a young Toni Basil, later of 1980s pop song “Mickey” fame), the JFK assassination, and nuclear apocalypse. From psilocybin mushrooms to nuclear mushroom clouds, his films asked audiences to see vexing connections, the fragmentation of consciousness, the body as a kind of war zone, and the dizzying, speed-up whir of modern life. Droll and suggestive without being didactic or pedantic in the least, Conner’s films proposed a counterculture far more complex and fraught than that of figures such as fellow psychedelic traveler, novelist Ken Kesey. Kesey and his group of “Merry Pranksters” ingested LSD and extolled the multitudes that freedom was to be found simply by “being in your own movie.”[6] Freedom was not so easily achieved in Conner’s films.

Conner also got involved in the early development of the light shows that began to appear behind rock bands in San Francisco’s psychedelic ballrooms. He made mandala drawings for Haight Ashbury’s underground newspaper, The Oracle, and for the programs accompanying historic events such as the Trips Festival in 1966. His imprint is less clear than Kesey, Leary, and others who found fame as spokesmen for the counterculture, but overall, Conner lurks almost constantly in the background of key countercultural scenes and moments. His cutting-edge work even presaged the performance art of the 1970s when he put himself, his wife Jean, and a woman named Vivian Kurtz on display for hours at a time, often naked, in a long jewel box vitrine in a show at San Francisco’s Batman Gallery in 1964. By the 1970s itself, he embraced the burgeoning punk rock scene, playing harmonica and photographing bands and audiences at San Francisco’s famous Mabuhay Gardens club.

Later chapters in The Artist in the Counterculture expand upon themes that Crow associates with Conner. The escalating Vietnam War produced potent counterculture art by San Francisco figures such as Wally Hedrick (Jay Defeo’s partner when she was making The Rose and Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia’s art teacher at the San Francisco Art Institute), particularly a set of black paintings and an enclosed box that entrapped audiences. Like Conner, Hedrick brought together the themes of a pressurized self and the expansive reach of US foreign policy. David Hammons, Corita Kent, Martha Rosler, Rupert García, and others in the “mother ship of California,” as Crow calls it, similarly connected queries into the nature of the self to the politics of the Cold War and did so with hallucinatory intensity. In their art, they portrayed individuals trapped by the stars and bars of the American flag or mixed banal scenes from middle-class American homes with horrible images of the war in Indochina (6).

Other artists such as Terry Fox, Michael Heizer, and Robert Smithson began to make Earth Art, which Crow wants us to notice was grounded, as it were (or perhaps, better said, floated on), in the “largely forgotten occultism” that was “woven through much of the conceptual, performance, and process art” of the late 1960s and into the 1970s (146). Earth Art itself was not named for “any prosaic acknowledgment of excavated matter,” he points out, “but rather as an analogue to the status of Earth as one of the four ancient elements (along with Air, Fire, and Water), which mapped onto the four bodily humors and in turn the four temperaments (Melancholic, Sanguine, Choleric, and Phlegmatic)” (146). Hippie-dippie astrological musings swirled together with serious, industrial-scale interventions into place and power. Architectural blueprints merged with zodiac charts. Bulldozers moved loads of dirt by way of starry-eyed, supernatural rhetorical flourishes.

This kind of “atavistically analogical thinking” cracked open epistemological boundaries, messed with time, and sought to rethink the world. It did so not to escape reality, but rather by building things within the real world, things that were of it, in conversation with it, around it, and often under it (146). One look at Smithson’s famous Spiral Jetty gives a sense of this mysticism. It was submerged at the remote northern end of the Great Salt Lake for many years and was meant, eventually, to dissolve into the briny waters in which it had been placed. With drought, Spiral Jetty came to the surface, but a visitor still had to embark on a pilgrimage to see it. The experience is, to Crow’s point, one of solidarity and awe, the feeling of becoming an isolated self lost in the vast, sublime expanse of the North American West.

Yet, in line with Crow’s argument, this self is quickly linked to larger social and political matters at Spiral Jetty. Next to the artwork are the hulking, rusty remnants of extraction equipment from an old effort to locate oil. On the other side of the lake is restricted land that turns out to be a US Air Force testing site (when I visited Spiral Jetty, a fighter jet actually dropped a bomb on the site, just to bring the point home that war and violence were never far from hippie mysticism’s explorations of the self in the world). Here is precisely Crow’s point about countercultural art: the trippy derangement of the ego was always profoundly linked to the violence and terror of American conquest by militaristic or other means.

Crow ends his book with an homage to Los Angeles-by-way-of-Michigan artist Mike Kelley. Kelley’s influences included Sun Ra, the Afrofuturist band leader, Archie Shepp, and other African American free jazz musicians who inspired a more cross-racial counterculture than has typically been acknowledged by historians (Bruce Conner was also involved with the radical theater activists group The Diggers, an offshoot of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, who in turn forged alliances with the Oakland-based Black Panthers, who in turn borrowed ideas for their free breakfast program from the Diggers’ free food programs in the Haight Ashbury[7]). These messier connections speak to a more unruly counterculture, one less easily pigeonholed as only a superficial, white, middle-class, bourgeois rebellion.

Kelley’s work from the 1970s also carries forward a more tangled and intricate countercultural legacy. His Catholic Birdhouse (1978), for instance, presents a workmanlike carpentry project: a birdhouse. While the bottom hole, labeled “the easy road,” is large and seems undamaged, the top hole is smaller and shows dents and nicks all around it, evidence of a more fraught and suffering path to self-salvation and collective liberation. It is labeled, of course, “the hard road” (237). This is the counterculture into which Crow wants us, following Conner, Kelley, and other artists, to enter. Not the easy way to innocence and bliss, but the tougher path to confronting reality in all its grim, challenging ways, and responding accordingly.

There, following Kelley’s work into the 1990s, Crow discovers a counterculture persisting just below dominant institutions of Cold War society, but also inextricably connected to them. The counterculture continued to manifest itself in shadowy, mysterious, and submerged ways, never quite apart from, but typically just below the mainstream, the dominant, the powerful, the hegemonic. As an example, Kelley’s Educational Complex (1995) features what at first appears to be a conventional architecture model of a typical postwar modernist academic building. It is sleek and modern. If the viewer crawls underneath the table upon which the model rested, however, and lies down on a solitary mattress on the floor to gaze upward, a catacomb-like basement of rooms and hallways appears below the typical architectural model.

This underside to the artwork looked much like the studio spaces in which Kelley and his students in fact were working in the minimalist art building at CalArts itself. Educational Complex signaled that the trendy Minimalism of the 1960s and 70s was a coverup. It tried to white out the messy, dense clutter and refuse of countercultural art. In fact, there was, in Crow’s words, “a mutually dependent convergence between an august institution of higher learning and networks of drugs, protest, and body-shaking music” (242). You could build order on top, but underneath, within, and below was a strange kind of anti-foundational energy always eating away at the thing. Something far more molten, fiery, and volcanic bubbled away down there in the belly of the beast. It needed the structure above to exist, but the structure above also somehow needed it too by the 1960s and thereafter.

If The Artist in the Counterculture wants us to discern anything it is this tethered quality of the institutions of power and of oppositionality in the 1960s and thereafter. The point is neither that the hegemonic forces commodified and conquered the resistant, nor that an oppositional movement overcame the dominant powers of the society, but rather that the two could not be cleaved apart from each other. The counterculture, in this art, by these artists, was always an encounter, an effort within the self and within postwar American and global life to locate counter-flows, to generate or to catch them, to cluster and clot them into gritty artifacts, to cut and cull them out of the very mainstream society itself and refashion them into meaningful messes, to enter, from below, into the main currents of the culture and pull them down into the murkier depths on which they moved, or maybe to cause something to erupt from deep within them, or perhaps to try to crawl toward something new and better, or at least to face up to the horrors as well as the pleasures of the world with greater honesty and go from there. The counterculture as portrayed here was indeed slouching toward Bethlehem, as Joan Didion, borrowing from Yeats, put it, but maybe that wasn’t such a bad thing.[8]

This was not an artistic movement about creating eternal masterpieces; it was more often about immediacy and intensity, what art critic Dave Hickey called the attempt to “actually peek into the emptiness” of the world. “Psychedelic art takes this apparent occasion for despair and celebrates our escape from linguistic control by flowing out, filling that rippling void with meaningful light, laughter, and a gorgeous profusion,” Hickey contends.[9] Crow does not quote Hickey in his book, but The Artist in the Counterculture certainly follows Hickey’s recollections and characterizations of the micro-generation to whom figures such as Bruce Conner were central. They thought of themselves as “freaks” (“We called ourselves freaks,” one Haight Ashbury participant explained to historian Alice Echols, “never hippies…hippies were people who borrowed your truck and didn’t return it”).[10]

Sandwiched between the Beats of the 1950s and the bubblegum hippies of the late 1960s, freaks turned to tools such as hallucinogenic drugs to dive into experience, to grasp how the personal consciousness of the self related to the politics of a postwar world dominated by militarized US imperialism in atomic bomb overdrive. They did not use drugs to escape into holy nirvana or naive innocence, but rather to confront both the deepest interior questions and the broadest exterior issues of being human during the Cold War. The “culture” they created in rock music, poster and album art, comic books, and other forms of expression, including the high art that Crow studies, “was a culture,” Hickey insists, “and a surprisingly social and public one.” While known “for all its apparent celebration of interior vision,” Hickey contends, “this art was always about the extension of that vision into the culture as a form of moral permission. It was a communal, polemical art, vulgar in the best sense and an international language.”[11]

It can be difficult to see this art and its historical significance through conventional means. For intellectual historians, Crow’s The Artist in the Counterculture serves as a good reminder that art history as practiced by the likes of Thomas Crow can help us glimpse ideas at play when they get embedded in artifacts beyond the conventional source base of the written word, philosophical tract, theological text, legal ruling, or economic transaction. Ideas also lodge themselves in visual materials. In this book, these are not even the “classics” of the 1960s artworld, but they nonetheless have many revelations if we want to offer. Yet intellectual historians often do not pay enough attention to art. Nor does intellectual history engage enough with the methods of art historical inquiry. To do so, following Crow, would be to see not only the culture in the counterculture, but also the ideas rapidly agglomerating below the surface of 1960s America, taking form in the edgy work of Bruce Conner and other artists who left traces of light in the mucky crust of the terrain that reaches right up to our own soiled times.

[1] Among too many books to name, see Damon R. Bach, The American Counterculture: A History of Hippies and Cultural Dissidents (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2020).

[2] One could think of this interpretation as one big elaboration of Frankfurt School thinking found in Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944; reprint, Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2002) or in Herbert Marcuse’s perceptions of “repressive desublimation” in One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society (1964; reprint, Boston: Beacon Press, 1991). See, also, George Melly, Revolt into Style: The Pop Arts (London: ? Allen Lane, 1970); Thomas Frank, The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1997); Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter, Nation of Rebels: Why Counterculture Became Consumer Culture (New York: Harper Collins, 2004; and David Brooks, David, Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000).

[3] Theodore Roszak, The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition (1969; reprint, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995). Often portrayed as a countercultural cheerleader, Roszak was in fact nothing of the sort. He was an older veteran of the Peace Movement who was hopeful, but was often quite critical and skeptical of the growing disillusionment with Cold War hyper-rationalism found among young Americans in the 1960s.

[4] Quoted from Daniel Abdal-Hayy Moore, “On Bruce Conner,” presented at the Memorial for Bruce Conner and published at Beats In Kansas: Beat Generation in the Heartland, http://www.vlib.us/beats/bconnermemorial.html.

[5] Ami Magill, phone conversation with author, 17 July 2007.

[6] On Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, see Tom Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (New York: Macmillan, 1968).

[7] See Black Panther David Hilliard’s comment about this, quoted in Timothy Hodgdon, Manhood in the Age of Aquarius: Masculinity in Two Countercultural Communities (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 25.

[8] Joan Didion, Slouching Towards Bethlehem: Essays (New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1968).

[9] Originally published as Dave Hickey, “Freaks Again: On Psychedelic Art and Culture,” Art Issues 31 (January/February 1994), expanded form gallery notes written to accompany “The Contemporary Psychedelic Experience,” Chapman University Guggenheim Gallery (March 17-April 27, 1993), revised for publication in Dave Hickey, Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy (Los Angeles: Art Issues. Press, 1997), 65.

[10] Quoted in Alice Echols, “Hope and Hype in Sixties Haight-Ashbury,” Shaky Ground: The ’60s and Its Aftershocks (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 30.

[11] Hickey, 64.

January 2, 2025

Explaining That After

Giorgio de Chirico, “L’incertezza del poeta” (“The Uncertainty of the Poet”), 1913.

Giorgio de Chirico, “L’incertezza del poeta” (“The Uncertainty of the Poet”), 1913.You can’t have ideas about things ahead of time. In our kind of criticism, one has to just come at stuff without too many preconceptions—though you can never be without them—and allow oneself to be struck by something. Criticism or interpretation is explaining that after. You can’t have a method that tells you what to do beforehand.

Kristin Strong’s The Servant Experience & the Servant Problem

January 1, 2025

The Dismantling of Higher Education

December 25, 2024

November 22, 2024

Syllabus—Modern America

Instructor Info

Instructor InfoDr. Michael J. Kramer, Department of History, SUNY Brockport, mkramer@brockport.edu.

Who is your instructor?Michael J. Kramer specializes in modern US cultural and intellectual history, transnational history, public and digital history, and cultural criticism. He is an associate professor of history at the State University of New York (SUNY) Brockport, the author of The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture (Oxford University Press, 2013), and the director of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project. He is currently working on a history of the 1976 United States bicentennial celebration and a study of folk music, technology, and cultural democracy in the United States. He edits The Carryall, an online journal of US cultural and intellectual history and maintains a blog of cultural criticism, Culture Rover. His website, with additional information about publications, projects, courses, talks, and more can be found at michaeljkramer.net.

What are we up to?You may think of history simply as the memorization of names and dates, and sure, we need to do some of that, but the study of history is really something far more intriguing. History asks us to figure out a seemingly simple question that gets complicated real fast, namely, how did we get here? This is the core question at stake in historical study. In our case, we will ask how we might better understand the development of the United States from the Civil War’s end in 1865 to our own times. What has changed in this duration of time, in this particular place? What continuities and themes do we notice? What caused what to happen—and, more complexly, why? History is about navigating all these questions, and other questions too, such as: whose history, exactly, do we wish to track? The rich and powerful? The everyday person? And why do we study history as we do, dividing it up by nations rather than other categories? How do all the elements of the past relate to each other, anyway? How do politics, economics, culture, ideas, beliefs, values, customs, environments, technologies, and social relationships connect, just to name a few aspects of the past?

Phew, lots of questions! Fortunately, history offers a method for navigating the messy, vast past as we try to not just memorize, but also give it some meaning. Which is to say history is more than just the feel-good myths we tell about America as a nation. History is more than just your opinion or what you feel. Instead, history is a multifaceted and multiperspectival set of stories we tell using empirical evidence or data to ask questions and come up with interpretations in dialogue with what others have had to say about the past. It is neither about one definitive truth, nor is it about anything goes. Instead it is about measuring and assessing a complex world with as much sophistication as we can muster. Sometimes the answers are simple; sometimes the evidence only produces more questions. History is made to handle both situations, which is why it can help you not only understand the past better, but also understand your own life more profoundly, and even, maybe, navigate your future with more dexterity, skill, and power. History is not a formula. It’s a craft for thinking about facts and truths and their many implications, connections, contexts, meanings, and mysteries.

So where do we start? First and foremost, history is about learning the craft of wielding evidence. We call the evidence our “sources.” They include artifacts of various types and kinds: documents, images, sounds, films, music, speeches, interviews, architecture, art, memories, and anything we can use to access the past. Questions come from what your close reading of the evidence suggests: what specific aspect of the evidence makes an impression on you? How can you put it in context with other bits of evidence to begin to paint a picture of the past? What questions does your close attention to the sources raise? What have other historians and people had to say about the topic at hand (a fancy word for this is “historiography”)? And what kind of convincing interpretation can you draw out of the sources and the existing interpretations of them to help us understand what happened more clearly and precisely?

How did we get here? Remember that this is the core question of history. And remember that the discipline offers a method you can learn to try to answer that question adequately. History, however, is not a science, not in the “natural” sciences sense. There is not usually one true answer (sometimes). The goal is not to achieve reproducible results or falsifiable claims (sometimes) as in the conventional scientific method. Yet history is more than just your opinion. It is based on empirical data. Instead of being reductive, it offers a method for handling complexity. In historical inquiry, there are a multiplicity of interpretations to consider, measure, grapple with, discuss, debate, and decide upon based on the empirical record (again, not your opinion, but your convincing interpretation and explanation of evidence).

So, in this course, we will learn what it means to practice the historical method as we explore the particular histories of the United States since the end of the Civil War in 1865. How did we get from that moment in time to now? What has changed? What continuities and themes have persisted? What kinds of interpretations and stories can we tell not based on what we want to believe or hope to believe or wish to believe about the United States, but rather based on the evidence?Through multimedia lectures, in-class assignments and discussions, at-home readings, writing assignments, and online assignments, you will learn more about what it means to study history, what it means to acquire the skills and capacities of thinking about the past and communicating your ideas about its sources and evidence more effectively. In doing so, you will not only leave this course with a better sense of the history of the United States over the last century and a half, but also with a better sense of how history can help you in whatever you wish to study, analyze, judge, or communicate to others when life gets complex. Sometimes the answers are simple, but as you grow older, you will see that most of the time they are not. Fortunately, history is here to help. For the skills of history are the very skills you will need not only to understand from where we have come, but also where you might want to go next.

Things you are expected to do this termBy taking this course you are agreeing to do the following to the best of your abilities:

Complete the readingsCome to class preparedParticipate in discussions in classComplete the assignments, using resources on campus such as the Academic Success Center and Drake Memorial Library to improve your research, writing, and reading comprehension skillsBe respectful of yourself, your instructor, and your fellow studentsRequired booksEric Foner, et. al., Illumine EBook Give Me Liberty! Volume II Brief 7th Edition (WW Norton, 2023)Eric Foner, et. al., Voices of Freedom Volume II, 7th Edition (New York: WW Norton, 2023)Available at Brockport BookstoreYou will need the digital Illumine EBook for this course, not the print version of Give Me Liberty! You may purchase the digital or the print version of Voices of Freedom as you wishAdditional assigned documents and resources on Brightspace course websiteSchedulesThe instructor may adjust the schedule as needed during the term, but will give clear instructions about any changes.

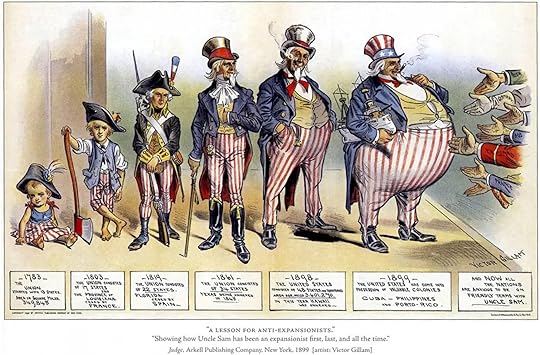

Meetings Schedule1865-1898Week 01 — Did the Civil War Ever End? The Reconstruction EraWeek 02 — The Hog Squeal of the Universe: The Arrival of Industrial CapitalismWeek 03 — Expansion and Incorporation: From Settler Colonialism to Formal Colonialism, Indian Wars to the Spanish-American War1899-1945Week 04 — What was the Progress in Progressivism? The Progressive EraWeek 05 — Making the World (or the US) Safe for Democracy? World War I and Its AftermathWeek 06 — The Roaring Twenties: Roars of Modernity…and AntimodernityWeek 07 — A Crisis of Industrial Capitalism: The Great Depression Arrives — Learning About Historical Methods of InquiryWeek 08 — Spring BreakWeek 09 — From Classic to Modern Liberalism: The Great Depression and the New DealWeek 10 — Did World War II Ever End? Mobilization and WWII1946-1969Week 11 — Containments and Rebellions of the Cold War: The FiftiesWeek 12 — Naming the System and Claiming Rights in the Sixties: Civil Rights, Vietnam, Social Movements, Countercultures, Backlashes1970-2024Week 13 — Disco Demolition: The Uncertain Seventies — Revolting Conservatives: The New Right Reagan Revolution in the EightiesWeek 14 — The Rise of Neoliberalism: The NinetiesWeek 15 — The War on Terror and Making America Great Again? Recent US History in Historical ContextReadings ScheduleWeek 01 — Did the Civil War Ever End? The Reconstruction EraGive Me Liberty!, Preface, xxiv-xxxviiGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 15, What Is Freedom?: Reconstruction, 1865-1877,” 441-474Voices of Freedom, Ch. 15, 1-27Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke. “What Does It Mean to Think Historically?,” Perspectives on History, January 2007Joel M. Sipress, “Why Students Don’t Get Evidence and What We Can Do About It,” The History Teacher 37, 3 (2004), 351-363Optional: American Historical Association Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct (updated 2023)Optional: Martin Pengelly, “A disputed election, a constitutional crisis, polarisation…welcome to 1876” (interview with Eric Foner), The Guardian, 23 August 2020Optional: Kevin M. Levin, “How Slavery Almost Didn’t End in 1865,” Civil War Memory, 6 December 2022Optional: 1865 Podcast (historical fictional)Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: John Daly, “The Southern Civil War 1865-1877: When Did the Civil War End?,” on BrightspaceWeek 02 — The Hog Squeal of the Universe: The Arrival of Industrial CapitalismGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 16, America’s Gilded Age, 1870-1890, 475-511Voices of Freedom, Ch. 16, 28-55Optional: Joshua Specht, “The price of plenty: how beef changed America,” Guardian, 7 May 2019Week 03 — Expansion and Incorporation: From Settler Colonialism to Formal Colonialism, Indian Wars to the Spanish-American WarGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 17, Freedom’s Boundaries, at Home and Abroad, 1890-1900, 512-545Voices of Freedom, Ch. 17, 56-77 Hopi Petition Asking for Title to Their Lands (1894), scroll down to read the transcription, especially p. 7Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94 (1884), Syllabus (full case optional if you are interested)Optional: Christine DeLucia, Doug Kiel, Katrina Phillips, and Kiara Vigil, “Histories of Indigenous Sovereignty in Action: What is it and Why Does it Matter?,” The American Historian, March 2021Week 04 — What was the Progress in Progressivism? The Progressive EraGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 18, The Progressive Era, 1900-1916, 546-577Voices of Freedom, Ch. 18, 78-106Optional: Various Authors, “Suffrage at 100,” New York Times, 2019-2020Optional Brockport Faculty Listening: Elizabeth Garner Masarik, “100 Years of Woman Suffrage,” Dig! A History Podcast, 5 January 2020Week 05 — Making the World (or the US) Safe for Democracy? World War I and Its AftermathGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 19, Safe for Democracy: The United States and World War I, 1916-1920, 578-611Voices of Freedom, Ch. 19, 107-135Optional: Noam Maggor, “Tax Regimes: An interview with Robin Einhorn,” Phenomenal World, 24 March 2022Week 06 — The Roaring Twenties: Roars of Modernity…and AntimodernityGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 20, From Business Culture to Great Depression in the “Roaring” Twenties, 1920-1932, 612-642Voices of Freedom, Ch. 20, 136-163Week 07 — A Crisis of Industrial Capitalism: The Great Depression Arrives — Learning About Historical Methods of InquiryGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 21: The New Deal, 1932-1940, 643- 675Voices of Freedom, Ch. 21, 164-190Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke. “What Does It Mean to Think Historically?,” Perspectives on History, January 2007Joel M. Sipress, “Why Students Don’t Get Evidence and What We Can Do About It,” The History Teacher 37, 3 (2004), 351-363Optional: American Historical Association Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct (updated 2023)Week 08 — Spring BreakWeek 09 — From Classic to Modern Liberalism: The Great Depression and the New DealGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 22, Fighting for the Four Freedoms: World War II, 1941-1945, 676-711Voices of Freedom, Ch. 22, 191-212Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Anne S. Macpherson, “Birth of the U.S. Colonial Minimum Wage: The Struggle over the Fair Labor Standards Act in Puerto Rico, 1938– 1941,” Journal of American History 104, 3 (December 2017), 656-680, on BrightspaceWeek 10 — Did World War II Ever End? Mobilization and WWIIGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 23, The United States and the Cold War, 1945-1953, 712-740Voices of Freedom, Ch. 23, 213-245Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Bruce Leslie (and John Halsey), “A College Upon a Hill: Exceptionalism & American Higher Education,” in Marks of Distinction: American Exceptionalism Revisited, ed. Dale Carter (Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 2001), 197-228, on BrightspaceWeek 11 — Containments and Rebellions of the Cold War: The FiftiesGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 24, An Affluent Society, 1953-1960, 741-772Voices of Freedom, Ch. 24, 246-269Week 12 — Naming the System and Claiming Rights in the Sixties: Civil Rights, Vietnam, Social Movements, Countercultures, BacklashesGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 25, The Sixties, 1960-1968, 773-807Voices of Freedom, Ch. 25, 270-305Optional: Keisha N. Blain, “Fannie Lou Hamer’s Dauntless Fight for Black Americans’ Right to Vote,” Smithsonian Magazine, 20 August 2020Optional: Freedom’s Ring: King’s “I Have a Dream” Speech website (The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University in collaboration with Beacon Press’s King Legacy Series)Optional: Lauren Feeney, “Two Versions of John Lewis’ Speech,” Moyers and Company, 24 July 2013Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Meredith Roman, “The Black Panther Party and the Struggle for Human Rights,” Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men 5, 1, The Black Panther Party (Fall 2016), 7-32Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Michael J. Kramer, “The Woodstock Transnational: Rock Music & Global Countercultural Citizenship After the Vietnam War,” The Republic of Rock Book Blog, 22 October 2018Optional Brockport Faculty Talk: R-E-S-P-E-C-T and the Social Movements of the SixtiesWeek 13 — Disco Demolition: The Uncertain Seventies — Revolting Conservatives: The New Right Reagan Revolution in the EightiesGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 26, The Conservative Turn, 1969-1988, 808-845Voices of Freedom, Ch. 26, 306-331Optional: Tim Barker, “Other People’s Blood,” N 1, 34, Spring 2019Optional: Moira Donegan, “How to Survive a Movement: Sarah Schulman’s monumental history of ACT UP,” Bookforum, 1 June 2021Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: James Spiller, “Nostalgia for the Right Stuff: Astronauts and Public Anxiety about a Changing Nation,” in Michael Neufeld ed., Spacefarers: Images of Astronauts and Cosmonauts in the Heroic Era of Spaceflight (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Scholarly Press, 2013), 57-76, on BrightspaceWeek 14 — The Rise of Neoliberalism: The NinetiesGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 27, A New World Order, 1989-2004, 846-886Voices of Freedom, Ch. 27, 332-345Week 15 — The War on Terror and Making America Great Again? Recent US History in Historical ContextGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 28, A Divided Nation, 887-933Voices of Freedom, Ch. 28, 348-367Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke. “What Does It Mean to Think Historically?,” Perspectives on History, January 2007Joel M. Sipress, “Why Students Don’t Get Evidence and What We Can Do About It,” The History Teacher 37, 3 (2004), 351-363Optional: American Historical Association Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct (updated 2023)Optional: Adam Serwer, “The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts,” The Atlantic, 23 December 2019, on BrightspaceAssignments ScheduleWeek 02 — DUE MONDAY 02/03Getting Started with Norton ToolsMake sure you can access Author Videos and Online ReaderStudent Info FormHistory Skills TutorialsAnalyzing ImagesAnalyzing MapsAnalyzing Primary Source DocumentsAnalyzing Secondary Source DocumentsNorton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 15 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 15Optional: Chapter 15 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineWeek 03 — DUE MONDAY 02/10Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 16 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 16Optional: Chapter 16 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineWeek 04 — DUE MONDAY 02/17Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 17 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 17Optional: Chapter 17 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineWeek 05 — DUE MONDAY 02/24Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 18 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 18Optional: Chapter 18 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineWeek 06 — DUE MONDAY 03/03Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 19 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 19Optional: Chapter 19 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineWeek 07 — DUE MONDAY 03/10Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 20 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 20Optional: Chapter 20 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineParagraph Assignment 01: Industrialization in the US After the Civil WarWeek 08 — SPRING BREAKWeek 09 — DUE MONDAY 03/24Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 21 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 21Optional: Chapter 21 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineANY LATE ILLUMINE AND INQUIZITIVE ASSIGNMENTS CH 15-20 LAST CHANCE DUE.Week 10 — DUE MONDAY 03/31Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 22 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 22Optional: Chapter 22 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineWeek 11 — DUE MONDAY 04/07Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 23 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 23Optional: Chapter 23 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineWeek 12 — DUE MONDAY 04/14Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 24 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 24Optional: Chapter 24 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineWeek 13 — DUE MONDAY 04/21Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 25 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 25Optional: Chapter 25 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineWeek 14 — DUE MONDAY 04/28Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 26 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 26Optional: Chapter 26 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineWeek 15 — DUE MONDAY 05/05Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 27 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 27Optional: Chapter 27 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineStart working on final assignments.FINAL — DUE MONDAY 05/10Paragraph Assignment 02: Progress or No?Norton Ilumine Ebook Chapter 28 Reading Comprehension QuestionsInquizitive: Chapter 28Optional: Chapter 28 Author Videos, Online, Flashcards, OutlineANY LATE ILLUMINE AND INQUIZITIVE ASSIGNMENTS FROM CH 21-28 LAST CHANCE DUE.EvaluationThis course uses a simple evaluation process to help you improve your understanding of both US history since the Civil War and history as a method. Note that evaluations are never a judgment of you as a person; rather, they are meant to help you assess how you are processing material in the course and how you can keep improving college-level and lifelong skills of historical knowledge and skills. Remember that history is a craft and it takes practice and iteration to improve, as with any knowledge and skill you wish to develop; but, if you keep at it, thinking historically can help you understand the complexities of the world more powerfully.

There are four evaluations given for assignments—(1) Yes!; (2) Getting Closer; (3) Needs Work; (4) Nah—plus comments, when relevant, based on the rubric below. Late assignments will lose one grade per each day they are late.

Remember to honor the Academic Honesty Policy at SUNY Brockport, including no plagiarism. In this course there is no need to use sources outside of the required ones for the class. The instructor recommends not using algorithmic software such as ChatGPT for your assignments, but rather working on your own writing skills. If you do use algorithmic software, you must cite it as you would any other secondary source that is not your own. For more information on SUNY Brockport’s Academic Honesty Policy.

5% Student Introduction20%—Paragraph Assignment 01: Industrialization in the US After the Civil War—Designing An Essay Assignment to Teach Change Over Time, Context, Causality, Contingency, or ComplexityObjective: Learn how to put together primary and secondary sources to develop a precise thematic argument about historical interpretation.5%—Illumine EBook Quizzes Part 0115%—Inquizitives Part 01Objective: Improve reading comprehension and interpretive analytic skills using evidence.25%— Paragraph Assignment 02: Progress or No?Objective: Learn how to put together primary and secondary sources to develop a precise thematic argument about historical interpretation.5%—Illumine EBook Quizzes Part 0215%—Inquizitives Part 02Objective: Improve reading comprehension and interpretive analytic skills using evidence.10%—Attendance, In-Class Worksheets, and Participation. Please note attendance policy below: you may miss up to four class meetings no questions asked, with or without a justified reason (this includes sports team travel, illness, or other reasons). You do not need to notify the instructor of your absences.Objective: Improve oral communication skills; improve skills interpretive analytic skills using evidence.Please note: I do not offer extra credit in this course.

Overall course rubricYes! = A-level work. These show evidence of:

clear, compelling writing assignments that include:a credible, persuasive argument with some originalityargument persuasively supported by relevant, accurate and complete evidencepersuasive integration of argument and evidence in an insightful analysisexcellent organization: introduction, topic sentences, coherent paragraphs, use of evidence, contextualization, analysis, smooth transitions, conclusionprose free of spelling and grammatical errors with lack of clichéscorrect page formatting when relevant, with regular margins, 12-point font, double spacedaccurate formatting of footnotes and bibliography with required citation and documentationon-time submission of assignmentsYour essay should include (as per Joel M. Sipress, “Why Students Don’t Get Evidence and What We Can Do About It,”The History Teacher, 37, 3, May 2004, on Jstor and Brightspace):Thesis—The “thesis” is the point that you are trying to prove. It is the thing of which you are trying to persuade the audience. It is your answer to the important question. A good thesis can usually be expressed in a sentence or two. The ability to formulate a clear and concise thesis is the fundamental skill of argumentation. One cannot argue effectively for a position unless it is clear what that position is.Summary—Arguments often take the form of a response to another person’s argument. In order to respond effectively to an argument, one must first be able to effectively identify and summarize that other person’s argument, including the other person’s thesis.Organization—In order to demonstrate a thesis, one must present points in support of that thesis. The persuasiveness of the argument depends largely upon the organization with which one presents the supporting points. The key to a well-organized argument is to present the supporting points one at a time in a logical order.Evidence—The fundamental criteria by which the persuasiveness of an argument should be judged is the degree to which specific evidence is provided that demonstrates the thesis and supporting points. The ability to locate and present such evidence is thus a fundamental skill of argumentation. Your essay should generally try to engage at least one, if not more than one, of the “5 C’s” as described in Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke. “What Does It Mean to Think Historically?,” Perspectives on History, January 2007. These are: Change over timeContextCausalityContingencyComplexityfor class meetings, regular attendance and timely preparation overall, plus insightful, constructive, respectful, and regular participation in class discussionsoverall, a thorough understanding of required course materialGetting Closer = B-level work, It is good, but with minor problems in one or more areas that need improvement.

Needs work = C-level work is acceptable, but with major problems in several areas or a major problem in one area.

Nah = D-level work. It shows major problems in multiple areas, including missing or late assignments, missed class meetings, and other shortcomings.

E-level work is unacceptable. It fails to meet basic course requirements and/or standards of academic integrity/honesty.

Successful assignments demonstrate:

Argument – presence of an articulated, precise, compelling argument in response to assignment prompt; makes an evidence-based claim and expresses the significance of that claim; places argument in framework of existing interpretations and shows distinctive, nuanced perspective of argument. Your argument should engage at least one of the “how to think historically” categories: change over time; context; causality; contingency; complexity. From Joel Sipress: Thesis—The “thesis” is the point that you are trying to prove. It is the thing of which you are trying to persuade the audience. It is your answer to the important question. A good thesis can usually be expressed in a sentence or two. The ability to formulate a clear and concise thesis is the fundamental skill of argumentation. One cannot argue effectively for a position unless it is clear what that position is.Evidence – presence of specific evidence from primary sources to support the argument. From Joel Sipress: Evidence—The fundamental criteria by which the persuasiveness of an argument should be judged is the degree to which specific evidence is provided that demonstrates the thesis and supporting points. The ability to locate and present such evidence is thus a fundamental skill of argumentation.Argumentation – presence of convincing, compelling connections between evidence and argument; effective explanation of the evidence that links specific details to larger argument and its sub-arguments with logic and precisionContextualization – presence of contextualization, which is to say an accurate portrayal of historical contexts in which evidence appeared and argument is being made. From Joel Sipress: Summary—Arguments often take the form of a response to another person’s argument. In order to respond effectively to an argument, one must first be able to effectively identify and summarize that other person’s argument, including the other person’s thesis.Citation – if required by assignment, wields Chicago Manual of Style citation standards effectively to document use of primary and secondary sourcesOrganization and Style – presence of logical flow of reasoning and grace of prose, including:an effective introduction that hooks the reader with originality and states the argument of the assignment and its significanceclear topic sentences that provide sub-arguments and their significance in relation to the overall argumenteffective transitions between paragraphsa compelling conclusion that restates argument and adds a final pointaccurate phrasing and word choiceuse of active rather than passive voice sentence constructionsFrom Joel Sipress: Organization—In order to demonstrate a thesis, one must present points in support of that thesis. The persuasiveness of the argument depends largely upon the organization with which one presents the supporting points. The key to a well-organized argument is to present the supporting points one at a time in a logical order.Citation and style guide: Using Chicago Manual of StyleIn this course, you can begin to grasp the use of Chicago Manual of Style.

There is a nice overview of citation at the Chicago Manual of Style websiteFor additional, helpful guidelines, visit the Drake Memorial Library’s Chicago Manual of Style pageYou can always go right to the source: the 17th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style is available for reference at the Drake Memorial Library Reserve DeskWriting consultationWriting Tutoring is available through the Academic Success Center. It will help at any stage of writing. Be sure to show your tutor the assignment prompt and syllabus guidelines to help them help you.

Research consultationThe librarians at Drake Memorial Library are an incredible resource. You can consult with them remotely or in person. To schedule a meeting, go to the front desk at Drake Library or visit the library website’s Consultation page.

Attendance policyYou will certainly do better with evaluation in the course, learn more, and get more out of the class the more you attend meetings, participate in discussions, complete readings, and finish assignments. That said, lives get complicated. Therefore, you may miss up to four class meetings, with or without a justified reason (this includes sports team travel, illness, or other reasons). You do not need to notify the instructor of your absences.

If you are ill, please stay home and take precautions if you have any covid or flu symptoms. Moreover, masks are welcome in class if you are still recovering from illness or feel sick.After six absences, subsequent absences will result in reduction of final course grade at the discretion of the instructor. Generally, more than five absences results in the loss of one grade per additional absences from final course evaluation.

Please note again: I do not offer extra credit in this course.

Disabilities and accommodationsIn accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and Brockport Faculty Senate legislation, students with documented disabilities may be entitled to specific accommodations. SUNY Brockport is committed to fostering an optimal learning environment by applying current principles and practices of equity, diversity, and inclusion. If you are a student with a disability and want to utilize academic accommodations, you must register with Student Accessibility Services (SAS) to obtain an official accommodation letter which must be submitted to faculty for accommodation implementation. If you think you have a disability, you may want to meet with SAS to learn about related resources. You can find out more about Student Accessibility Services or by contacting SAS via the email address sasoffice@brockport.edu or phone number (585) 395-5409. Students, faculty, staff, and SAS work together to create an inclusive learning environment. Feel free to contact the instructor with any questions.

Discrimination and harassment policiesSex and Gender discrimination, including sexual harassment, are prohibited in educational programs and activities, including classes. Title IX legislation and College policy require the College to provide sex and gender equity in all areas of campus life. If you or someone you know has experienced sex or gender discrimination (including gender identity or non-conformity), discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or pregnancy, sexual harassment, sexual assault, intimate partner violence, or stalking, we encourage you to seek assistance and to report the incident through these resources. Confidential assistance is available on campus at Hazen Center for Integrated Care. Another resource is RESTORE. Note that by law faculty are mandatory reporters and cannot maintain confidentiality under Title IX; they will need to share information with the Title IX & College Compliance Officer.

Statement of equity and open communicationWe recognize that each class we teach is composed of diverse populations and are aware of and attentive to inequities of experience based on social identities including but not limited to race, class, assigned gender, gender identity, sexuality, geographical background, language background, religion, disability, age, and nationality. This classroom operates on a model of equity and partnership, in which we expect and appreciate diverse perspectives and ideas and encourage spirited but respectful debate and dialogue. If anyone is experiencing exclusion, intentional or unintentional aggression, silencing, or any other form of oppression, please communicate with me and we will work with each other and with SUNY Brockport resources to address these serious problems.

Disruptive student behaviorsPlease see SUNY Brockport’s procedures for dealing with students who are disruptive in class.

Emergency alert systemIn case of emergency, the Emergency Alert System at The College at Brockport will be activated. Students are encouraged to maintain updated contact information using the link on the College’s Emergency Information website.

Learning goalsThe study of history is essential. By exploring how our world came to be, the study of history fosters the critical knowledge, breadth of perspective, intellectual growth, and communication and problem-solving skills that will help you lead purposeful lives, exercise responsible citizenship, and achieve career success. History Department learning goals include:

Demonstrate knowledge of major concepts, models and issues of US history since the Civil WarIdentify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they appear in their own and others’ workDemonstrate understanding of the methods historians use to explore social phenomena, including observation, hypothesis development, measurement and data collection, experimentation, evaluation of evidence, and employment of interpretive analysisDevelop proficiency in oral discourse through class participation and discussionArticulate a historical question and thesis in response to it through analysis of empirical evidenceAdvance in logical sequence principal arguments in defense of a historical thesisProvide relevant evidence drawn from the evaluation of primary and/or secondary sources that supports the primary arguments in defense of a historical thesisEvaluate the significance of a historical thesis by relating it to a broader field of historical knowledgeExpress themselves clearly in writing that forwards a historical analysisStart to learn disciplinary standards of documentation and citation when referencing historical sourcesSyllabus—Graduate Readings in Modern America

Instructor info

Instructor infoDr. Michael J. Kramer, Department of History, SUNY Brockport, mkramer@brockport.edu

Who is your instructor?Michael J. Kramer specializes in modern US cultural and intellectual history, transnational history, public and digital history, and cultural criticism. He is an associate professor of history at the State University of New York (SUNY) Brockport, the author of The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture(Oxford University Press, 2013), and the director of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project. He is currently working on a history of the 1976 United States bicentennial celebration and a study of folk music, technology, and cultural democracy in the United States. He edits The Carryall, an online journal of US cultural and intellectual history and maintains a blog of cultural criticism, Culture Rover. His website, with additional information about publications, projects, courses, talks, and more can be found at michaeljkramer.net.

What are we up to?How do we make sense of the United States since the Civil War both historically and historiographically? What are the stories? What are the debates about the stories among historians? We will read widely and deeply in the course to explore particular eras as well as the larger historical narrative. Even with all our reading, we are only skimming the surface of the rich world of historical scholarship, so we will try, in our weekly meetings, to situate our readings in larger questions, debates, and issues. With whom is each author in dialogue? What is each author arguing? What evidence does the author marshal to support or give rise to the argument? What methods does each author use? Students will read, discuss, and develop both short written analyses and in-class presentations to improve their understanding of modern America and their own historical and historiographic knowledge and skills.

Things you are expected to do this termComplete the readingsParticipate in class discussionsComplete the assignmentsAcquire a graduate student-level knowledge of US history since the Civil WarImprove critical thinking, communication, historiographic, research, and writing skillsSee SUNY Brockport website for additional History Department course objectivesOnline synchronous technology policyStudents in the online synchronous version of the course should log in to Zoom through a laptop or desktop computer with direct Ethernet or robust broadband wireless and, ideally, headphones with a microphone. Please be in a calm, quiet location (desk or table in a room, not in your car or out in the world). Keep your camera on during class if possible and mute your microphone when not speaking. In the case of unforeseen technology breakdown (sounds, video, etc.), students may be asked to makeup work during office hours or through an additional written assignment. Individual cases will be negotiated with the professor. Please consult with the professor about any questions concerning use of technology in the course.

Required materialsHahn, Steven. Illiberal America: A History. New York: W. W. Norton, 2024. 9780393635928Downs, Gregory P. and Kate Masur. The World the Civil War Made. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015. 9781469624181Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: W.W. Norton, 1991. 9780393308730Hunter, Tera W. To ’joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1997. 9780674893085Kasson, John F. Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century. New York: Hill and Wang, 1978. 9780809001330Rodgers, Daniel T. Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000. 9780674002012Ngai, Mae M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America – Updated Edition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014. 9780691160825Cohen, Lizabeth. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939. 1990; 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press, 2008. 9780521715355Delmont, Matthew F. Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad. New York: Viking, 2022. 9781984880413Payne, Charles M. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995. 9780520251762Frank, Thomas. The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1997. 9780226260129Zaretsky, Natasha. No Direction Home: The American Family and the Fear of National Decline, 1968-1980. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007. 0807830941Moreton, Bethany. To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010. 9780674057401Hyden, Steven. There Was Nothing You Could Do: Bruce Springsteen’s “Born In The U.S.A.” and the End of the Heartland. New York: Hachette Books, 2024. 9780306832062Lichtenstein, Nelson and Judith Stein. A Fabulous Failure: The Clinton Presidency and the Transformation of American Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023. 9780691245508Beck, Richard. Homeland: American Life in the War on Terror. New York: Crown, 2024. 9780593240229Meetings and readingsThe instructor may adjust the meetings schedule as needed during the term, but will give clear instructions about any changes.

Week 01Tu 01/28

Hahn, Steven. Illiberal America: A History. W. W. Norton & Company, 2024. 9780393635928, Introduction, Ch 01Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke. “What Does It Mean to Think Historically?,” Perspectives on History, January 2007Week 02Tu 02/04

Hahn, Steven. Illiberal America: A History. New York: W. W. Norton, 2024. 9780393635928, Ch 2-ConclusionWeek 03Tu 02/11

Downs, Gregory P., and Kate Masur, eds. The World the Civil War Made. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015. 9781469624181Week 04Tu 02/18

Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: W.W. Norton, 1991. 9780393308730, especially Prologue-Part II, read all if you can.Week 05Tu 02/25