Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 6

November 10, 2024

Phonies

a garden of pure ideology…

— Big Blue dictator, Apple 1984 advertisement

…I like to think

(right now, please!)

of a cybernetic forest

filled with pines and electronics

where deer stroll peacefully

past computersas

if they were flowers

with spinning blossoms.

I like to think

(it has to be!)

of a cybernetic ecology

where we are free of our labors

and joined back to nature,

returned to our mammal

brothers and sisters,

and all watched over

by machines of loving grace.

— Richard Brautigan, All Watched Over By Machines Of Loving Grace

In both the story of the Garden of Eden and in the myth of Prometheus, the fact that humans have to work is seen as their punishment for having defied a divine Creator, but at the same time, in both, work itself, which gives humans the ability to produce food, clothing, cities, and ultimately our own material universe, is presented as a more modest instantiation of the divine power of Creation itself. We are, as the existentialists liked to put it, condemned to be free, forced to wield the divine power of creation against our will, since most of us would really rather be naming the animals in Eden, dining on nectar and ambrosia at feasts on Mount Olympus, or watching cooked geese fly into our waiting gullets in the Land of Cockaygne, than having to cover ourselves with cuts and calluses to coax sustenance from the soil.

— David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs

As Apple advertisements often have done in the past, the new Apple commercials for their version of the AI fad, which the company has branded Apple “Intelligence,” clarify matters of technology and culture in the United States. Apple demonstrates how AI has never been about intelligence, certainly not in its most recent incarnation, but rather it has been about the production of affect, of emotion. AI is not being directed at thoughts, but rather at feelings. Miserable with your life, but don’t want anyone to see it? AI can be your shield. Bored out of your gourd by your job? AI can be your front of expertise and interest. Seething with rage inside at your unhappy marriage? Let your AI be your Superego.

To understand how Apple’s new ads emerge from a long story of Apple commercials as screens mirroring the state of the American self and American society, it’s worth going back to 1984. Recall one of the most famous television advertisements of all time, Apple’s 1984 Superbowl halftime commercial, directed by Alien/Bladerunner director Ridley Scott, in which a platinum blonde young woman in tank top and red track shorts, a kind of “Let’s-Get-Physical” Olivia Newton-John of the future, jogs into a meeting of zombified workers with shaved heads, gas masks, and dazed looks. They sit on benches listening to a pallid gray video indoctrination by a scary Nazi-like dictator. She outruns the riot police goon squadrons to spin around and hurl a hammer into the screen of Big Brother, I mean Big Blue: IBM as a fantasy of Orwellian totalitarian control over the masses, whom the Macintosh is about to liberate so that “you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984’,” as the ad put it.

The Macintosh was to revolutionize society, striking a blow for freedom, letting loose the repressed-hippie rainbows in an oppressive, stagflated, Reaganimited post-1960s America. Cybernetics rises from the acidic ashes to bring you, the alienated individual, along with the masses, back to the garden of individuality, innocent and reborn and ready to be your creative and authentic self, not so much watched over by a machine of loving grace, as Richard Brautigan fantasized at the countercultural apex of the Summer of Love itself in the 60s, so much as blending with the machine, identifying with its smiley face greeting, making nice, and inthe process making your self free by buying access to the Mac’s Garden of Eden. It was as if someone was running the Adam and Eve story in reverse. The apple, er, um the Apple, didn’t banish you from paradise with knowledge; it returned you to it. The snake was just a cute little mouse. With one click you were free. Purchase a little “personal” computer to become your own self-made machine of loving grace.

The 1984 ad was all about how Apple opposed the Man, man. It was anti-system. Earlier this year, however, Apple seemed to turn totalitarian itself. Perhaps befitting the growing interest in authoritarianism and mood of the nation and world, now Apple seemed to have become the empire instead of opposing it. In a new advertisement for the IPad Pro, the company borrowed from a social media video fad of crushing things with a hydraulic press to show various symbols of artmaking and creativity—trumpets, an upright piano, brushes, paint cans, a Space Invaders vintage video game machine that reads Game Over on it, a turntable, a video monitor with an alarmed animation character on it, an acoustic guitar, books, a wooden figurine, an emoji doll getting its eyes popped out—being compressed into the thinnest, sleekest, blackest, most Imperial Empire-looking Ipad Pro ever.

Cue the music from Star Wars. Dumb-dum-da-dumb-da-da-dumb. Except what we heard instead was the faintly countercultural-sixties pop flowers-in-your-hair soundtrack of Sonny and Cher’s “All I Ever Need Is You.” The unspoken message was, of course, “all you will have is us.” The point of the ad was supposed to be, I suppose, that all one needs to be creative is an Ipad Pro. The new Ipad compresses all that creativity and history of culture making into this amazing device that puts everything at your fingertips. Maybe it will even be creative for you if you just buy it.

The press was on here, however, as if Apple was suggesting that if you do not purchase an Ipad Pro, you would be crushed yourself. Here was the only way to keep up with the “creatives.” Join the platform or die. Pony up the big bucks and you would soar into the Iclouds. Your only path to self-expression and authentic creativity would be by way of the device. This was the Orwellian Big Blue of 1984’s Superbowl commercial turned inside out. The hammer-throwing woman in the red shorts bursting in on the totalitarian world to destroy the screen of control—was she Eve perhaps?—had now been crushed back into it. “The most powerful Ipad ever…is also the thinnest,” a female voice calmly told us after the trauma of what we had just witnessed.

The new Intelligence ads take this reversal even further. But it’s worth stopping first to notice how Apple commercials during the festive neoliberal era of the 2000s began to turn the hammer-throwing woman of 1984 into a mere silhouette of the machine itself. These were the years of the Ipod, the device that seemed to liberate massive libraries of music from the CD tower but in fact tethered users down to the Apple platform. As cool young people danced stylishly across abstracted splashes of color, they were but shadows. Only the portable device and its headphone cables were lit up in bright white, set against their negative-space bodies.

These ads marked a step along the way toward the ongoing saga of Apple as a screen for American perceptions of individuality. Ipod, Iphone, Ipad. You are only a self if you have one. Of course most Americans don’t use Apple products. They are too expensive. Nonetheless, in the advertisements for this elite consumer item, we can perceive the fever dreams of American selfhood, dreams of achieving authentic individuality by way of linking the self into a cyborgian blending with consumer technology. This pursuit of selfhood, however, is also always a presentation of how to feel a sense of belonging. With our device, on our platform, on our Icloud, and now with our “Intelligence,” saith Apple, you will find your perfection, you will be as one with the animals and whales in the cybernetic meadows and forests and ecologies. You will (right now, please!) find yourself. And…if you don’t, you ignorant fool, if you can’t dance happily to our IPod beat, then we will, intelligently of course, find you.

In the latest advertisements for Apple’s new version of AI, called, simply, ominously, “Intelligence,” we see this even newer kind of American self on display. She is descended from the hammer-hurling woman in red shorts, but barely so. This one is no Olympian athlete arriving to liberate, but rather almost the opposite. She is a hollowed out failure of a human in despair. Everyone is utterly alienated, feels like an idiot, experiences staggering moments of awkwardness, is bored and alone, is sadder than can be, and doesn’t see the point of much of anything. The new Apple user persona is not a creative rebel, but an exhausted, anesthetized, estranged sack of nothing. They do not hurl the hammer, they have been hammered into oblivion. Addicted to our phones, we have become a nation of phonies.

Here comes Apple to save the day, to save our feelings, with automation.

Some of the ads address the emotional experience of what David Graeber called “bullshit jobs,” the need of capitalism to create a world of pointless work when automation suggests that humans could spend more time trying to figure out what actual freedom and a free society might be. An African American man who hasn’t prepared for a board meeting is asked to explain a business prospectus; having no idea what the prospectus states, since he hasn’t done the reading, as it were, and with the implication that the whole thing is bullshit anyway, and so are all the jobs of the people sitting around the table high up in a shiny, sleek office tower, he comically slides his fancy chair away for a minute, quickly summarizes the prospectus on his laptop using Apple Intelligence, and fudges his way through leading the meeting.

Similar ads feature a young woman. She is at a fancy lunch pitch meeting and has to summarize some kind of novel or film proposal she has not read. She uses Apple Intelligence to “summarize” it and, as with the managerial businessman at the meeting mentioned above, bullshits her way through responding to the person pitching her at the lunch. Is actual human engagement needed here? No. Precisely the opposite. The summary zaps out the fact that the pitch she did not read features a “unique relationship.” The woman looks up from her phone to her overeager lunchmate. “I love unique relationships,” she remarks. Of course, the whole point of the ad is that neither this meeting or possibly any of these lunches involves one! “With a twist,” says the lunchmate. The twist is that the whole thing is total bull. Life’s business relationships couldn’t be any more monotonous, exhausted, and less unique. What are we but just a bit more code for the machine, to be summarized without knowing the actual particulars of the story.

At the end of the ad, the woman gazes for a moment at the camera, conspiratorially. You don’t actually want real human interaction either, her look suggests. You know you are just bits and bytes in the matrix of fakeness too. What you really want to do is just want to go home and doomscroll (itself a kind of labor for the system of the attention economy, maybe one more productive and valuable than any business meeting now). Who needs this responsibility and empty social interaction? It doesn’t add up to anything necessary. It is unreal. The setting is fancy and the drinks are overpriced and you can put it all on the corporate credit card as a business expense. What the moment calls for is total fakery. Fakery is, Apple suggests, intelligence now. Where have you gone, hammer-hurling woman of 1984? What liberation is this now, in 2024? What is real, the woman’s closing glance and twisted smile proposes, slyly, is using AI to step out of the dying emotional connections and interactions of the past. Her look is a hurled hammer. Come be numb with me, she seems to say with her eyes.

The sleek silver office fridge door closes and we see a young, mustachioed man in glasses and a red sweater. He is a bit reminiscent of Theodore, Joaquin Phoenix’s deeply alienated office worker in the 2013 dystopian techno film Her. Someone has stolen his homemade pudding again. Outraged, he composes an angry, seething email and is about to send it to the whole office when he glimpses a little teddy bear on a woman’s desk a few cubicles away. On its red sweater, the saying: “Find Your Kindness.” He turns to Apple Intelligence to revise his email into a “friendly” tone. Sending it off with its affective tone remade, magically a cute woman appears from nowhere to return his glass jar with his name on it to his desk. She apologizes. We see him at the end of the ad chowing down on his pudding joyously, all alone, finding a meager sad solitary pleasure in an otherwise utterly alienating environment.

A third man is bored out of his mind at the office. He is about to send an informal, borderline rude email to his boss about how dumb the current project his team is working on is. Then Apple Intelligence allows him to “professionalize” the message so that he can recommend his colleague for fixing it. Presumably this makes him look good while also getting him out of doing any work. The ad ends with him swinging a paper clip chain around as if it were nunchucks and he a karate mastermind.

These ads are all oddly evocative of The Office, with its painful alienations of characters adrift and alone in the world, looking for something better but utterly unable even to name, never mind pursue, what that freedom might entail. Whatever a satisfying life of “loving grace” might be, to return to Brautigan’s poem, this isn’t this. We are back in Apple’s 1984 totalitarian nightmare, only now it is not the Man creating a world of alienation, and not even clearly the system. It is just life, a completely enfolding world of meaninglessness. In 1984, so far as Apple was concerned, the enemy was clear. Their audiences, trapped in automaton posture, forced to listen to the speech of Big Blue, longed for a hammer to hurl at the screen in order to break free. Buy the Mac and you’ve got your hammer, the ad proposed. Now, automation is proposed as liberation. AI is both hammer and screen. Use our device not to liberate yourself but to bullshit your way through your un-freedom.

Maybe the most striking of the AI Intelligence ads, the most chilling and, in its way, the most shockingly ominous of all features a wife and mother who has forgotten her husband’s birthday while her daughters present him with (nothing less than!) a hammer (here’s to you 1984!), with his initials impressed neatly in the wood. The wife and mother of the family, meanwhile, stands in the kitchen watching them. She looks tired, frayed, harried. She sadly stops pouring her first cup of coffee for the day and looks desperately around for what she can do to save face. Does she actually love her husband? Or her daughters? Does she really even want to be there in this middle-class family?

It would seem not, but she has to play the part. So she whips out her Iphone, hits up the Intelligence feature, and creates an instant slideshow of nostalgic authentic family memories to bring over to the couch and show her husband and daughters. Having successfully bullshitted her way past not actually caring about his birthday at all, or about him, or about her daughters, or maybe about her entire life, she walks out of the room, away from any actual emotional engagement with them (Apple Intelligence has done the emotional work). Like the woman at the pitch meeting and other protagonists of the Apple Intelligence ads, she too gazes conspiratorially at the viewer at the end of the commercial while a snatch of Krizz’s stuttering hip-hop song “Genius” grows louder and louder.

Genius, according to Apple in 2024, seems to be about about avoiding any kind of actual attachment or commitment. To me the word in the song also sounds like “chaos,” but maybe that doesn’t matter as much as a bigger point: whereas the “1984” ad proposed that the “personal” computer could offer escape to freedom by way of purchasing a Macintosh, 2024’s Apple Intelligence ads suggest that all one can do is achieve a kind of dull, cynical escapism within the total enclosure of the system.

There is no way out now. In “1984,” automation and what we might call the threat of an automatonic life was the problem. The Macintosh would help you escape it. Now, Apple’s business plan demands that automation become the solution. The point is not to hurl a hammer into the system of control’s authoritarian leader, with his ugly, looming, leering, threatening face, but rather to throw it into yourself, to automate all aspects of your life, from work life to family life to any other forms of intimacy. Don’t get free, says Apple Intelligence; rather desensitize. Click. Swoosh. You’re done.

Apple used to present itself as a technological tool for your creativity and discovery of self-expression. Now, says the company, let us take that weight off your shoulders. We will handle all that bullshit. You will find freedom in our total domination of your life, your social relations, your very self. Creativity is for suckers. Sincerity is for fools. You are a failure at everything, anyway. Finding your authentic self is a joke. Given the situation, Apple’s Intelligence ads propose, intelligence is now about forsaking it. Or at best just faking it. Not faking it until you make it, mind you, but making it because you fake it. Embrace the bullshit by buying an Apple product. Take a bite of our knowledge and we will help you see better how that paradise of emancipation to yourself is but a virtual reality trick of the headset. There is no yourself. We are yourself. You are nothing but an empty hardshell case for our product.

There is some kind of narcotic dimension to the Apple Intelligence ads, but the kind borne of terror. The AI seeks to replace actual intelligence with the fleeting feeling of successful trickery. Yet it does not suggest absolution from this act of deception. Sure, the protagonists get away with things thanks to their Apple products, but they also get further away from themselves. Somehow the product sells not only deceit but also self immolation as a pleasurable activity. There is no forbidden fruit anymore, only the compost trash heap of bullshit from start to finish. Not even existential angst is a concern now. Apple will take care of free will too, along with everything else, automating true feelings into socially permissible ones, engineering affectlessness into emotion. Whatever it was that the original apple from the tree of knowledge delivered to humankind, Apple seeks to reverse it. Yet we are not getting back to the garden here. The desire is no longer to be all watched over by machines of loving grace. Now we are simply all machined over by watchers.

October 27, 2024

Big Shoes to Fill

Art Bridgman and Myrna Packer in Ghost Factory.

Art Bridgman and Myrna Packer in Ghost Factory.Art Bridgman and Myrna Packer’s dance work, Ghost Factory, uses a combination of live performance and recorded video to explore the vast, vacant spaces of a shut-down shoe factory in Johnson City, New York, near Binghamton. More crucially, the two-person dance work seeks to evoke the spectral stories of those who once labored in the factory. Blending bodies and machines, the hour-long piece strives to summon the vanished lifeworld of working-class activities in the shoe factory, which of course come from an earlier era when bodies and machines also interacted. The interplay of stage and screen thus becomes a meditation on the past interplay of workerly embodiment and industrial production. We are watching, in the present, bodies and machines as they interact in a performance about a now-historical moment of bodies and machines interacting. In this sense, Ghost Factory also becomes an investigation of the contemporaneous and the historical, the present and the past, now and then.

Within, behind, sometimes right through video projections on scrims and sometimes on large, rectangular, moveable blocks of fabric, the two dancers, dressed elegantly in dress and black shirt and pants, elegantly paced, twirled, bent down, raised up hands to the sides or ceiling. Sometimes they seemed to be stitching shoes, particularly in a wonderful solo by Bridgman in which he sat sideways to the audience in a chair and repeated the motion as four duplicates of him appeared on the screen doing the same thing. At another point, filmed from above on the screen, Packer rolled across the floor of the factory. Then she also rolled out from below the scrim across the floor of the stage, tipping the sense of orientation into a dizzying displacement of space. Where were we exactly? In the factory? In the theater? In the past? In the present? We found ourselves increasingly somewhere liminal, maybe in a corridor or tunnel of memory, in transition.

Overall, by appearing in the video and on stage, by playing with space both in the filmed sequences and in the theater itself, Bridgman and Packer strived, calmly, to bring to the present bygone times and peoples. There was a sense of dignity to the affair in the portrayals of bodies at work, bodies remembering old motions and movements and feelings. It culminated in a lovely couple dance scene to jazz. As the video seemed to transform into an abandoned basement music club stripped to the crumbling concrete walls, on stage Bridgman and Packer clutched and held each other, spun and swayed. They leaned on each others’ shoulders before parting ways.

The dynamic of screen and stage, video and embodiment, renders a layered and textured work about absence and presence, about things vanishing and things persisting, about memory and immediacy and how they might, possibly, relate to each other. Screen and stage even blur in Ghost Factory until you sometimes cannot tell the difference between the two. A real body dancing in the theater arises out of the shadow of the same body in the factory space of the video. An interior space of pipes and peeling paint and dripping pools of water sometimes seemed bigger than the theater itself. It threatened to absorb the stage into its epic emptiness. At one point, a pond of water in the video rippled across the two dancers on screen in the factory and it almost felt as if the stage itself was getting wet. Displaced multiple times over, from embodiment on stage to video to abandoned factory to the life that used to inhabit the filmed spaces, everything began almost to dissolve into, or at least ripple across, the theatrical space of the now. What was real and what was projected, what was embodied and what was ghostly, what was being brought to life before your eyes and what was long gone became almost indistinguishable.

Ghost Factory seemed to want to go back, to bring life to the past and the past to life; but ultimately, however, the sense was that this might be impossible. “All gone,” a woman’s voice from an oral history interview rang out through the theater sound system, taken from an oral history recording of a former worker at the shoe factory, “All gone.” Ghosts leapt up before us, both in bodies and in pixels, but eventually they both exhausted themselves and flickered away. We were left with a sense of sad abandonment, of forlorn loss. It wasn’t tumultuous so much as peaceful, mournful, a kind of service, an acknowledgment. One could even say that the performance entailed an unburdening. It did not excavate the past so much as summon it up to say goodbye to it. At the same time, if you wanted to notice, there were invisible spirits all around, their phantasmic fading hands trying to hang on, still stitching, with shoes whose orders remained to be completed.

Toward the end of the performance, Packer stopped suddenly and bent over, letting one arm swing back and forth, like the pendulum of a grandfather clock. Time was ticking, and there was really no strategy of screen or body, video or dance, that could stop it. The more the dancers tried, with elegance and grace, to resuscitate the world of the factory and its working people, the more forcefully the sense of emptiness and lostness intensified. The video was high definition, but the memories grew oddly more grainy, indefinite, shadowy. The screen was bright, but eventually the bodies disappeared into the dark. History had its way. In a ghost factory, some shoes you cannot fill, some scrims you cannot cross.

Bridgman|Packer Dance: Ghost Factory TrailerOctober 23, 2024

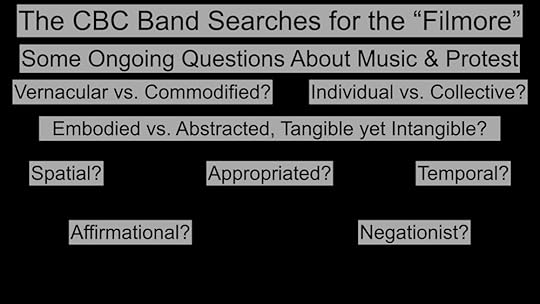

The CBC Band Searches for the “Filmore”

A brief talk delivered for Music & Protest in Historical Perspective, an online panel sponsored by the LePage Center for History in the Public Interest, Villanova University.

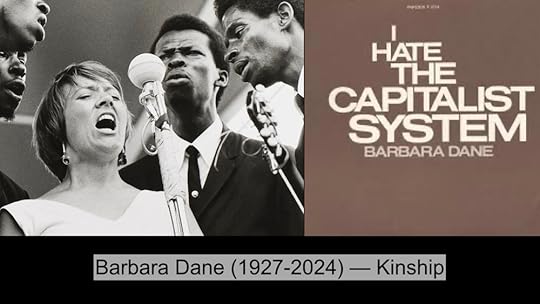

I want to begin with a quote from the great musician and political activist Barbara Dane, who died at 97 just a few days ago. A life well lived. She remarked to a reporter from the Guardian, while in hospice no less, “There’s a power in music that unites people. You can take a roomful of people and make them feel their kinship in a way that nothing else can with a song.”

It is this sense of kinship, particularly what anthropologists call “fictive kinship,” that I want to use as a kind of spotlight for my brief comments for this panel.

In my own research on rock and folk music in the 1960s and 70s, I repeatedly noticed how music broadened the nature of what we mean by protest, primarily through its capacities to foster a sense of kinship.

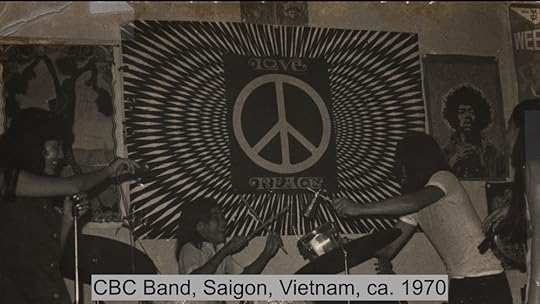

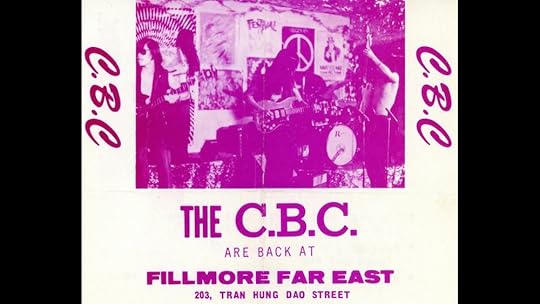

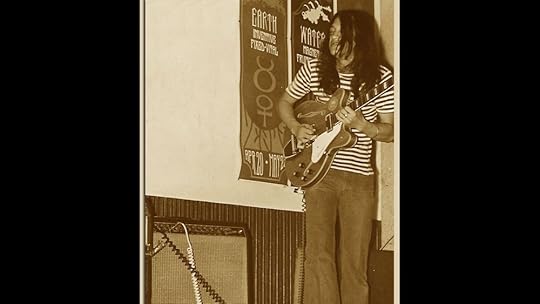

Here we see the Vietnamese rock band the CBC. Kinship is quite literally on display here, as the band consisted of a family of brothers and sisters.

But kinship also gets complex, and very quickly. With whom did CBC’s music foster kinship, exactly?

The group became known as the Beatles of Saigon when they played in the seedy nightclubs during the Vietnam War, as well as on US military installations, also at traditional Vietnamese weddings, and even at the…

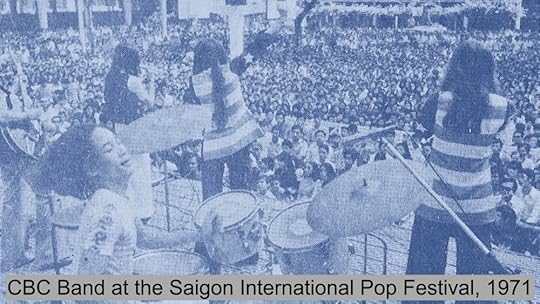

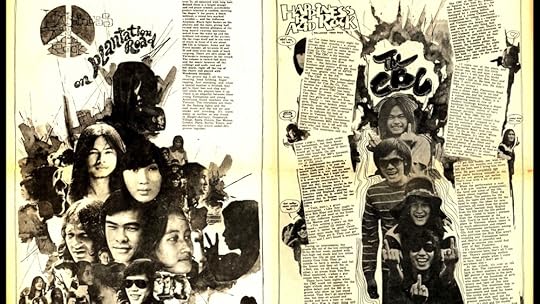

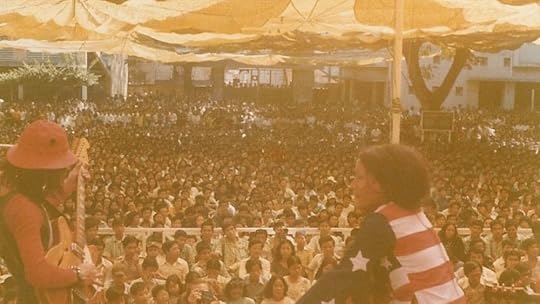

…Saigon International Pop Festival, an event modeled on the famous Woodstock Festival in upstate New York in August of 1969.

Yet the Saigon International Pop Festival was no rebellion against the mainstream, exactly. It was not even clearly anti-Vietnam War. It was, in fact, organized by pro-war elements within South Vietnam, as a benefit for injured troops in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam.

So here is no simple “which side are you on” story of music as protest: a seemingly antiwar event, Woodstock, now became associated with pro-war parts of South Vietnamese society.

Of course, the event was really about dreaming of no war, given that it was about trying to generate funds for injured soldiers. Yet it was not clearly antiwar, as rock music is often imagined during the 1960s. It was something far more complex than simple, direct protest. It was about the more amorphous possibilities of multidimensional kinship.

CBC’s kinship was no simple thing. Playing the latest rock hits from “back in the world,” as Americans in VIetnam called the US and England, and all places not Southeast Asia, and playing them virtually note for note, CBC became quite popular with many different groups. They were beloved by local Vietnamese youth, known as cowboys, who rode around on motorbikes with existential dread and a sense of nihilistic rebellion amidst a war of occupation. CBC also became extremely beloved by American military personnel, much to the dismay of the official US brass, who despite the band’s appearance as headliners at a pro-war event, nonetheless associated CBC’s acid rock with the decay of morale among US military personnel, who were losing interest in waging the war and instead getting caught up in a hedonistic warzone smog of marijuana smoke and a swirl of psychedelic electric guitar howls. The international population living in Saigon loved CBC too.

They were the hippest band to know or to go see, at clubs with names such as Plantation Road, Sherwood Forest, the My Phoung club, and the Fillmore Far East.

The only people who did not like CBC alongside the US military brasss seemed to be their opposition: the Communist-oriented VIetcong, who bombed the band at a club performance in Saigon in 1971, supposedly in the midst of the CBC’s performance of Jimi Hendrix’s song, “Purple Haze.” The bomb killed a young woman who had dated CBC’s drummer and injured some of the band members.

So what kind of protest, if it even was protest, did CBC mount with their music? What kind of kinship did they invoke? Was their music merely a vessel for a kind of imperial American soft power: the exportation to the war zone of a hip capitalist rock culture that seemed to offer liberation, but in fact incorporated young people into the very systems of empire—whether military or commercial—from which they thought rock music announced a departure? Was plugging in to the rock amplifier merely a way of getting wrapped up in its wires?

Or, was CBC’s rock music a kind of protest, a sound of many people coming together to reject the larger forces making their lives so miserable with war, violence, alienation, and division? Was rock music a way to give the finger to the authoritarian forces creating this havoc and suffering, to flip the bird at the fools in charge?

Did CBC’s rock music even become an outpost, a sort of alternative induction center, for a nascent Woodstock Nation, a different country or republic of rock that many yearned to join? Was CBC part of a kind of Woodstock Transnational that sprang up within American channels of military and commercial power but was not ever entirely quite of it, instead beckoning with a freak flag of a peace symbol painted within the American flag, waving their long hair at the possibility of a different configuration of kinship, belonging, and participation—a different mode not just of kinship, but of citizenship even—than what the US or Vietnam or any other entity could offer? Could music really do that? Or was it just an American ruse, a false flag of freedom that was not really a form of protest at all?

Even when CBC arrived as refugees in the United States in 1975, after wandering through India, Bali, and Thailand without a home, they continued to perform rock music. Settling eventually in Indiana, then LA, and now Houston, CBC continued to search for the elusive Fillmore Auditorium, the San Francisco club where countercultural hippie acid rock in part began. Misspelled here with one “l,” the band poses by the roadside, as if looking to find a ride to the Fillmore, ready to set out to find, if not exactly of music club in San Francisco where acid rock had first made its anarchic, hedonistic clang of electricity known, or its sister club the Fillmore East in New York City, which Fillmore promoter opened a few years later, or even the aforementioned Fillmore Far East that CBC had performed at in Saigon, but rather maybe a symbolic Fillmore of the mind—or maybe we could say of the ear: the “Filmore” that stood for a fleeting but potent sense of collective kinship, a feeling of mutuality and affiliation generated by music that arose within systems of oppression—militarism, capitalism, racism, xenophobia, misogyny, patriarchy, alienation, exploitation—yet nonetheless harnessed aspects of that system’s technologies and instruments to propose alternatives. CBC did so from within the very channels of power themselves, diverting them in surprising directions out of a war zone and into an American, yet also an international, tale of collective discovery.

Was this a form of protest? If so it wasn’t a simple “which side are you on?” one. Maybe it was a kind of protest that did something else, something more fraught and human, but also courageous and inspiring in its way. For did not CBC try to fashion the dream of finding a more fulfilling—hmm, maybe we could even say a more fulfillmoreing?— life out of the very circuitry of American military and commercial power that seemed to entrap them and so many others in difficult lives? They seized not only the means of production in an economy shifting toward symbolic, affective, and information commodification, but they also seized the means of consumption in this shifting, fragmenting mass consumer society that had figured out ways of commodifying cool, of selling rebellion, adapting its possibilities for their own pursuits of freedom, fun, and even of security (they were, after all, paradoxically using hedonistic Western youth culture to keep their together their family, that basic unit of traditional Vietnamese culture!).

With CBC, we can start to ask more fraught questions about music and protest, difficult questions. Here are a few that I would say are worth more debate and discussion:

How is music at once a vernacular form of expression and also capable of becoming a commodity? What even is the nature of music as a commodity when it comes to protest and politics? And what is the nature of music as part of vernacular expression: whose vernacular expression exactly?How is music the expression of individuals and individual autonomy or liberation or emancipation or resistance or dissent? And how do its individual dimensions relate to its deeply communal and collective qualities and capacities?How do we think about music as both embodied, which is to say produced with muscles and vocal cords, heard with eardrums and auricular nerves, echoing in chest cavities and making feet and hips move, at the same time that it is also abstract and ephemeral, time-based and symbolic and intangible? For music is bodily and not bodily. And it often makes noise precisely at the boundary between bodies and between bodies and other things: institutions, the walls of particular rooms, even up to the sky and the very heavens above.Music takes up space. But how, in taking up space, does music, this tangible yet also intangible form of expression, generate forms of protest?Music’s spatial dimensions speak to another key issue: cultural appropriation. For music is at once deeply embedded in particular social locations, bodies, peoples and yet it travels across boundaries. It permeates. When is music capable of being appropriated and bent toward new modes of protest—say, an old Baptist hymn turned into a radical IWW Wobbly criticism of the capitalist system, or then a labor song turned into a civil rights movement protest anthem, or the CBC taking American rock music and making it speak for them and their situation and needs—and when is appropriation more problematic, exploitative, and dangerous?Moreover, music is not just spatial, it is also temporal. Music happens in time. It can be timely, and it can take one out of time. Sometimes we even say music is timeless! But what do we mean when we say this, exactly? How does music’s temporal nature relate to its capacities to mount protest?

How is music at once a vernacular form of expression and also capable of becoming a commodity? What even is the nature of music as a commodity when it comes to protest and politics? And what is the nature of music as part of vernacular expression: whose vernacular expression exactly?How is music the expression of individuals and individual autonomy or liberation or emancipation or resistance or dissent? And how do its individual dimensions relate to its deeply communal and collective qualities and capacities?How do we think about music as both embodied, which is to say produced with muscles and vocal cords, heard with eardrums and auricular nerves, echoing in chest cavities and making feet and hips move, at the same time that it is also abstract and ephemeral, time-based and symbolic and intangible? For music is bodily and not bodily. And it often makes noise precisely at the boundary between bodies and between bodies and other things: institutions, the walls of particular rooms, even up to the sky and the very heavens above.Music takes up space. But how, in taking up space, does music, this tangible yet also intangible form of expression, generate forms of protest?Music’s spatial dimensions speak to another key issue: cultural appropriation. For music is at once deeply embedded in particular social locations, bodies, peoples and yet it travels across boundaries. It permeates. When is music capable of being appropriated and bent toward new modes of protest—say, an old Baptist hymn turned into a radical IWW Wobbly criticism of the capitalist system, or then a labor song turned into a civil rights movement protest anthem, or the CBC taking American rock music and making it speak for them and their situation and needs—and when is appropriation more problematic, exploitative, and dangerous?Moreover, music is not just spatial, it is also temporal. Music happens in time. It can be timely, and it can take one out of time. Sometimes we even say music is timeless! But what do we mean when we say this, exactly? How does music’s temporal nature relate to its capacities to mount protest?A few last questions that I think bring us to the heart of the matter:

In what ways is music affirmational? How is it a way of agreeing, of controlling, of establishing rules and boundaries and limits, of creating kinship through agreements, whether tacit or overt? Or, to put affirmation in a positive framework of inclusivity, how do we recognize music as protest when it is a way of saying, as the jazz classicist Wynton Marsalis noted of swing music, “come on in.”At the same time, how has music also negated, or expressed refusal, or asserted dissent and resistance? Or to quote a song by the radical folk singer Utah Phillips, how do we hear and understand music better when it does not affirm, but rather declares ”I will not obey!”

These are meant to be generative questions, intended to keep us thinking, to keep the song of music and protest going, not close the ongoing composition with some kind of triumphant crescendo of an answer. Music sustains, even in silence. So should our attention to its historical relationship to protest. Then we can better understand the ways in which, as another giant who left us recently, the civil rights activist and singer Bernice Johnson Reagon, put it, music has allowed people to “charge the air with our power.”

October 6, 2024

Rattle & Hum

Jim White. Photo: David Harris.

Jim White. Photo: David Harris.Writer Jon Carroll once wrote that the Band’s Levon Helm was “the only drummer who can make you cry.” One could add Jim White to the list. Across many different ensembles, the Australian drummer does not so much keep the beat as rattle and hum along its surfaces, cresting and bobbing, as if his kit were a rickety vessel tossed along the foam of the sea. There is something oceanic below, to be sure, in his playing, but it is as if we observe it all from across the surface of his snare as his sticks, like needles on a compass, jab, spinning out the navigation, pointing the way.

When White plays, where are we headed? Toward dawn or dusk? When one is in constant motion, moving slow among continents, across hemispheres, what’s really the difference? It is perpetual twilight. In the blueness, the world feels epic yet also like a sprinkle of teardrops too, a scattering of rain clouds, a pin prick of star points. We dip and soar between small and large. All is rumble, not arrival. The world becomes gravitational and celestial all at once. We are on top of minerals and ores, crust and salt, valley beds and cliffhangers, back channels and, above us, endless space punctuated by glimpses of dramatic constellations.

One might not at first notice White’s presence. It is spectral until you start to pay attention to it at the margins. Then the percussion starts to creep across consciousness, limbs akimbo, bending and motoring underneath, reaching out overhead with a shake and a nod.

On the recordings of one of his core groups, the instrumental ensemble the Dirty Three, his drums even take the lead at times. In the band’s holy dirges, we are placed in a conversation as White, along with Warren Ellis on violin and Mick Turner on guitar, blend and diverge. They sometimes almost fall apart, but then they move together, like three men rowing a boat, mostly in tandem, sometimes in disagreement. Ellis and Turner’s instruments can at times almost become the rhythmic elements and White’s skittering variations direct the journey. Other times, Turner or especially Ellis take a turn at the helm. Then White’s drums become like wind through the planks, creaking oars, a gurgling wake, rustling leaves in the trees on distant banks, pebbles and rocks tossed across the water, waves lapping up to the shoreline. Here are three men thrown together, generating soaring swells of sound that fade into quiet places.

White is an ensemble player of the finest sort. Alongside his work with the Dirty Three, a conversational quality defines his support for other musicians. One could say that his percussion is, in some sense, all about accompaniment. In songs on which he drums, he is the listener’s avatar, listening. He is interested in lending a hand, giving a push, pillowing a fall, guiding a dream, enjoying a quip, absorbing a pain, commending wisdom, questioning possibilities, acknowledging dilemmas, making sure that a healthy clatter props up the songs.

The quality of White’s drumming slyly aids, for instance, the searching, searing, husky sadness and yearning of Cat Power’s classic Moon Pix, keeping pace with Chan Marshall’s puzzled inquisitions pace for pace, stroke for stroke, bringing new textures out of the depths of her remarkable lower register, sinking and rising again with her, cymbals crackling and burbling, snare drum snapping an urgent response when needed.

One hears the same qualities surface again on Anna and Elizabeth’s The Invisible Comes to Us, where once more the drums do not keep the beat so much as grace the pulse with accents, brimming with ideas, emerging and submerging again, asking the singers to say more, then receding into the background to listen and carry on.

One might understand Jim White as a kind of avant-grade Bernard Purdie, the “hitmaker” with his distinctive shuffle. Like Purdie, you might not notice White at first. His drumming is all for the song. He’s in the background, never intrusive. But the more you pay attention, the more the backbeat foregrounds, the more one appreciates the support, until you realize that he’s been dragging ghost notes across the collective consciousness all along, ringing in your ears.

In Jim White’s drumming is, perhaps most of all, the evocation of a certain sense of time, a kind of endlessness, a sustained looseness, a restlessness that is not worried about agitation but embraces its possibilities. This playing is full of oxygen. There is a spaciousness that also contains a haunting graciousness. The sticks kiss, click, tap, strike, pat, patter, nudge, touch, and simmer. We escape in hiss, riding along into what is, ultimately, a fundamental gesture to the power of silence: the grace notes, the echo, the reverberation, the thoughts that float.

September 22, 2024

Exceptionally Unexceptional

Kirsten Dunst and Cailee Spaeny in Civil War. Photo: Murray Close/A24.

Kirsten Dunst and Cailee Spaeny in Civil War. Photo: Murray Close/A24.But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground.

— Abraham Lincoln

Is American exceptionalism over? One might think so watching Alex Garland’s intriguing, but actually quite conventional, war movie Civil War.

What’s odd is that the film could actually care less about the reasons for the civil war it portrays in a future—but not too distant future—United States. The President has become a tyrannical dictator, but in the end, there is no greater cause, no civic religion, no deeper quasi-religious project of America’s purpose in the world that informs this civil war. The war does not echo the original Civil War between North and South. It even pairs up California and Texas as the “Western Forces,” as if to distance itself from any contemporary blue state-red state comparisons. In this movie, the US civil war is just like any other war anywhere else in the world: a confusing sprawl of factions and a lot of carnage and nastiness and brutality. “July 4th, July 10th, West Coast forces, fuckin’ Heartland Maoists, it’s all the same,” remarks Joel, the journalist played by Wagner Moura, to his colleagues, the photojournalist Lee Smith, played by Kirstin Dunst, and grizzled older journalist Sammy, played by Stephen McKinley Henderson. In this film, American exceptionalism is dead.

In place of any political or quasi-mystical meaning, Civil War is really just a standard-issue war correspondent film to rival the best of them, such as The Killing Fields, The Year of Living Dangerously, Salvador, Full Metal Jacket, and Foreign Correspondent. We track the seemingly unflappable Lee Smith as she starts to lose it among the destruction, first mentoring a younger photographer, Jessie, played by Cailee Spaeny, then being replaced by her. Jessie eventually, of course, steps into Lee Smith’s shoes, or in this case puts her younger finger on her once invincible master’s shutter button. Civil War is a gripping, finely filmed remake of this archetypal Bildungsroman, in which the protégé ultimately replaces the guru.

Along the way, however, Garland creates rather shocking images, at least to any American who thinks of the United States as somehow different and immune to the forces of conflict that have riven other parts of the world. We see a war-torn domestic America in flames, both in its cities and in the countryside. Yet there is no rhyme or reason for who is fighting whom and over what. None of the political dimension of the story is explained much at all. The president has turned dictator, the country has fragmented. That’s about it in terms of political backstory. There are even areas, such as one surreal town the war correspondents pass through, in which no war seems to be going on at all. It is a baffling landscape, one there primarily as backdrop to the journey into oblivion taken by Lee Smith, young acolyte Jessie, sidekick Joel, and wizened newshound Sammy.

Which is to say, we are not only in a conventional war correspondent film, but also in a road movie. Sometimes it feels a bit like following Martin Sheen’s Benjamin L. Willard up river to find Marlon Brando’s Captain Walter E. Kurtz in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, but not really since what the Civil War crew finds at the end is not particularly illuminating in the least. It is just more banal conquest, captured in images for posterity. You can barely remember the name of the president in the film, and certainly not why he was able to consolidate power and subsequently unleash such a monumental collapse of his country.

There are moments of hope during the trip, such as when the journalists spend a night at a rescue camp in an abandoned stadium where people seem to be finding community amid the anarchic decimation of violent conflict. So too, there are incidents of sheer terror, such as a renegade militia nationalist, played by the now reliably creepy Jesse Plemons, whom the journalists come upon burying bodies in a mass grave (what has become of you, earnest Landry Clarke of Friday Night Lights?). Which side is he on? What happened to create such mass death? Why is he handling the bodies in such a callous way? It all goes unexplained.

Stylistically, the film creates a particularly effective contrast between edgy scenes such as this one, which offer a surreal, sometimes exhilarating apocalypse (now) landscape of war, and then numerous frozen image stills taken by the photojournalists of the atrocities and violence they witness. It is as if they want to try to freeze in time the chaos to give it a kind of order—reifying it, commodifying it, and almost, but never quite entirely, endowing the war with a meaning and purpose that the film itself keeps undercutting. The silence snaps in the silent snaps. They try to hold something in place, maybe a spiritual hush that might make it all worth it, but Garland refuses to grant such relief.

Instead of comprehending why this civil war has happened, one is left by the end of the film asking: meaning in war, what’s that? Civil War suggests there is no larger meaning. Violent conflict is just a pointless shattering, a wreckage, even in a nation that imagines itself on an exceptional track, leading the way toward progress, with a godly mission to serve as a beacon on a hill, spreading the light of freedom, democracy, and justice. The United States of Civil War is no exception. It is not distinctive from other places or peoples. No, Garland suggests. If an American civil war comes again, it will not be much different from anywhere else.

Watching the film, I was put in mind of a remark North Vietnamese war veteran and writer Bao Ninh made in Lynn Novick and Ken Burns’ documentary about the Vietnam War, a civil war whose ghost haunts the movie Civil War far more than the actual American Civil War of the nineteenth century. “Who won or lost is not a question,” Ninh comments. “In war, no one wins or loses. There is only destruction.” In Civil War, an American civil war, like any war, would be uncivil, but it would not be special. The war provides a rush of adrenaline to its war correspondents, and to the viewers witnessing the war through their eyes and through the eyes of their cameras. Yet, like any addiction, the feeling ultimately proves hollow, empty, devoid, nihilistic.

Maybe the addiction to American exceptionalism has reached its conclusion too, Civil War proposes. For Americans, one hopes, the film offers a powerful, sobering lesson. Civil war, American style, will not bring about anything particularly unlike anywhere else. There is only destruction in that direction, as Bao Ninh points out, and no solace in a US version of civil strife. Good riddance, then, to American exceptionalism. But not to the hope that wars of any sort can be avoided, anywhere they might break out.

Unexceptional

Kirsten Dunst and Cailee Spaeny in Civil War. Photo: Murray Close/A24.

Kirsten Dunst and Cailee Spaeny in Civil War. Photo: Murray Close/A24.But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground.

— Abraham Lincoln

Is American exceptionalism over? One might think so watching Alex Garland’s intriguing, but actually quite conventional, war movie Civil War.

What’s odd is that the film could actually care less about the reasons for the civil war it portrays in a future—but not too distant future—United States. The President has become a tyrannical dictator, but in the end, there is no greater cause, no civic religion, no deeper quasi-religious project of America’s purpose in the world that informs this civil war. The war does not echo the original Civil War between North and South. It even pairs up California and Texas as the “Western Forces,” as if to distance itself from any contemporary blue state-red state comparisons. In this movie, the US civil war is just like any other war anywhere else in the world: a confusing sprawl of factions and a lot of carnage and nastiness and brutality. “July 4th, July 10th, West Coast forces, fuckin’ Heartland Maoists, it’s all the same,” remarks Joel, the journalist played by Wagner Moura, to his colleagues, the photojournalist Lee Smith, played by Kirstin Dunst, and grizzled older journalist Sammy, played by Stephen McKinley Henderson. In this film, American exceptionalism is dead.

In place of any political or quasi-mystical meaning, Civil War is really just a standard-issue war correspondent film to rival the best of them, such as The Killing Fields, The Year of Living Dangerously, Salvador, Full Metal Jacket, and Foreign Correspondent. We track the seemingly unflappable Lee Smith as she starts to lose it among the destruction, first mentoring a younger photographer, Jessie, played by Cailee Spaeny, then being replaced by her. Jessie eventually, of course, steps into Lee Smith’s shoes, or in this case puts her younger finger on her once invincible master’s shutter button. Civil War is a gripping, finely filmed remake of this archetypal Bildungsroman, in which the protégé ultimately replaces the guru.

Along the way, however, Garland creates rather shocking images, at least to any American who thinks of the United States as somehow different and immune to the forces of conflict that have riven other parts of the world. We see a war-torn domestic America in flames, both in its cities and in the countryside. Yet there is no rhyme or reason for who is fighting whom and over what. None of the political dimension of the story is explained much at all. The president has turned dictator, the country has fragmented. That’s about it in terms of political backstory. There are even areas, such as one surreal town the war correspondents pass through, in which no war seems to be going on at all. It is a baffling landscape, one there primarily as backdrop to the journey into oblivion taken by Lee Smith, young acolyte Jessie, sidekick Joel, and wizened newshound Sammy. We’re not only in a conventional war correspondent film, but also a road movie. Sometimes it feels a bit like following Martin Sheen’s Benjamin L. Willard up river to find Marlon Brando’s Captain Walter E. Kurtz in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, but not really since what the Civil War crew finds at the end is not particularly illuminating in the least. It is just more banal conquest, captured in images for posterity. You can barely remember the name of the president in the film, and certainly not why he was able to consolidate power and subsequently unleash such a monumental collapse of his country.

There are moments of hope during the trip, such as when the journalists spend a night at a rescue camp in an abandoned stadium where people seem to be finding community amid the anarchic decimation of violent conflict. So too, there are incidents of sheer terror, such as a renegade militia nationalist, played by the now reliably creepy Jesse Plemons, whom the journalists come upon burying bodies in a mass grave (what has become of you, earnest Landry Clarke of Friday Night Lights?). Which side is he on? What happened to create such mass death? Why is he handling the bodies in such a callous way? It all goes unexplained.

Stylistically, the film creates a particularly effective contrast between edgy scenes such as this one, which offer a surreal, sometimes exhilarating apocalypse (now) landscape of war, and then numerous frozen image stills taken by the photojournalists of the atrocities and violence they witness. It is as if they want to try to freeze in time the chaos to give it a kind of order—reifying it, commodifying it, and almost, but never quite entirely, endowing the war with a meaning and purpose that the film itself keeps undercutting. The silent snaps try to hold something in place, a spiritual hush that might make it all worth it, but Garland refuses to grant such relief.

Instead of comprehending why this civil war has happened, one is left by the end of the film asking: meaning in war, what’s that? Civil War suggests there is no larger meaning. Violent conflict is just a pointless shattering, a wreckage, even in a nation that imagines itself on an exceptional track, leading the way toward progress, with a godly mission to serve as a beacon on a hill, spreading the light of freedom, democracy, and justice. The United States of Civil War is no exception. It is not distinctive from other places or peoples. No, Garland suggests. If an American civil war comes again, it will not be much different from anywhere else.

Watching the film, I was put in mind of a remark North Vietnamese war veteran and writer Bao Ninh made in Lynn Novick and Ken Burns’ documentary about the Vietnam War, a civil war whose ghost haunts the movie Civil War far more than the actual American Civil War of the nineteenth century. “Who won or lost is not a question,” Ninh comments. “In war, no one wins or loses. There is only destruction.” In Civil War, an American civil war, like any war, would be uncivil, but it would not be special. The war provides a rush of adrenaline to its war correspondents, and to the viewers witnessing the war through their eyes and through the eyes of their cameras. Yet, like any addiction, the feeling ultimately proves hollow, empty, devoid, nihilistic.

Maybe the addiction to American exceptionalism has reached its conclusion too, Civil War proposes. For Americans, one hopes, the film offers a powerful, sobering lesson. Civil war, American style, will not bring about anything particularly unlike anywhere else. There is only destruction in that direction, as Bao Ninh points out, and no solace in a US version of civil strife. Good riddance, then, to American exceptionalism. But not to the hope that wars of any sort can be avoided, anywhere they might break out.

September 1, 2024

Tents

Tents on the campus of Columbia University, April 2024. Photo: CS Muncy for the New York Times.

Tents on the campus of Columbia University, April 2024. Photo: CS Muncy for the New York Times.Two photographs of tents appeared on the front of the New York Times website one day in April 2024.

In each photo, clusters of nylon fabric, green and white, were staked down in some kind of public space. At first glance, it was easy to think they were the same public space, but they were not.

In one photograph, tents were pitched on the campus at an elite university, part of a protest movement against Israeli military actions in Gaza and the ongoing fraught issue of Israeli policy toward Palestinians as well as the failure to achieve a lasting, just peace in that long-running and painful conflict.

The other photograph, however, featured tents that were not tethered at all to the protests on campuses against the war in Gaza. These other tents formed part of a homeless encampment in a West Coast city in the United States. They were featured as part of a story about a Supreme Court hearing in which municipalities were seeking (and won eventually) the right to remove temporary homeless encampments even when they were unable to house the people in them somewhere else safe.

Homeless encampment in Grants Pass, Oregon, March 2023. Photo: Mason Trinca for the New York Times.

Homeless encampment in Grants Pass, Oregon, March 2023. Photo: Mason Trinca for the New York Times.Elsewhere in the Times a few months earlier, it should be noted, were even more photographs of tents, this time the large beige canvas ones that NGOs or the United Nations or other agencies often use. In this case, they housed Palestinians living on the beaches of Gaza itself, trying to survive amid the rubble of wartime.

Tents in Gaza, Fall 2023. Photo: Samar Abu Elouf for the New York Times.

Tents in Gaza, Fall 2023. Photo: Samar Abu Elouf for the New York Times.What meanings did these tents conceal? What did they reveal? To be sure, at the most obvious level, they were just tents, objects for trying to keep your head dry in the rain, stay warm in the cold, and cool in the heat, no matter what the situation. The tents were places to survive, maybe to get a little privacy even when placed in public places or crowded together in unwelcome locations. In the homeless encampments and in Gaza, the tents were signs of distress, of life in peril, of precariousness. On campuses, they were more symbolic, intended to stand out against the permanent structures of learning and living built around them. They were raised in solidarity, yet they also came to stand for a sort of signal of distress, this time the alarm at life proceeding normally close by when a disturbing conflict was going on overseas.

Tents raise tension because they mark out temporariness. Putting down stakes raises the stakes. Like little flares of color, they mark out public territory with private dwellings, they assert a nomadic uncertainty, they point out the failures of those in power to create more sustainable and permanent living establishments. Tents polarize.

Tents can be beautiful, sacred things, or pleasurable sites of social gathering. They can express a sense of living lightly on the land, a oneness with the natural world, or an eloquent mobility. The Lakota tipi, for instance, is a temporary structure not only of great practical use, but also of enormous awe and grandeur. The Bedouin beit ash-sha’ar (house of hair) tents can sometimes look more comfortable, secure, and practical in pictures than most suburban split levels. The hiker on an expedition carries her tent with her, a home on her back. The ability to set down home at will, wherever you want, helps to produce the relaxed intensity of life on the trail. Tents can evoke a peacefulness, an adaptability, a harmony, even a feeling of abundance. Wherever you go, there you are. Or think of the circus or carnival tent, with its spectacular wonders and perhaps its whiff of a bit of exciting danger on the edge of town. You might even want to join it if you aren’t fitting in at home and desire a road to escape and freedom.

Not in the case of these photographs, however. In these images, tents tended to rise up in places they were not supposed to be: on fancy campus quads; in that patchy, neglected strip of park by the courthouse or downtown square; along Mediterranean beaches. They became fragile monuments, symbols of precariousness, vulnerability, suffering, shock, outrage, a growing feeling of unease. In the spring of 2024, the nylon and canvas hung on tensile poles, stretched out to the point of ripping. Flapping in the wind, they were set against the fraying social fabric.

August 31, 2024

Rovings

Charlie Chaplin and Jackie Coogan in The Kid, 1921.SoundsMoscow Notebooks, BBC SoundsSevern, BBC SoundsJoe Jones on UbuwebWorld Turned Upside Down, Season 01William Eggleston, Memphis, NTS Radio, 24 July 2023Norman Thomas discusses the book Great Dissenters, part 1, 11 November 1961, Studs Terkel Radio ArchiveNorman Thomas discusses the book Great Dissenters, part 2, with Lillian Smith, 11 November 1961, Studs Terkel Radio ArchiveIkue Mori, Robert Quine, Marc Ribot, Painted DesertMarion Brown, “Iditus”K.Z. Morogoro Jazz Band, “Nikupendeje”Louis Armstrong, “I Hope Gabriel Likes My Music”Louis Armstrong Orchestra, “Cain and Abel”Henry Flynt, Hillbilly Tape MusicEugene Chadbourne, *There’ll Be No Tears TonightBelle and Sebastian, “Everyday People”Arrested Development, “People Everyday”WordsClaire Messud, This Strange Eventful HistoryEd Park, Same Bed Different DreamsAaron Cometbus, Despite Everything: CometbusMark Davidson and Parker Fishel, Bob Dylan: Mixing Up the MedicineHunter Dukes, “Kojève & Cigarettes,” Cabinet, 29 August 2024Gabriel Winant, “We Can Breathe!,” London Review of Books, 1 August 2024Joshua P. Hill, “Late Capitalism Turns to Fascism: The rich are looking for a bailout,” New Means, 11 July 2024K. Sabeel Rahman, “Building the Government We Need: A Framework for Democratic State Capacity,” Roosevelt Institute, 6 June 2024Evgeny Morozov, “Can AI Break Out of Panglossian Neoliberalism?,” Boston Review, 31 July 2024Wesley Morris, “Meshell Ndegeocello Could Have Had Stardom but Chose Music Instead,” New York Times, 1 August 2024Shalon van Tine, “A Failure of Vision,” CounterPunch, 13 March 2022Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi, “James Baldwin in Turkey: How Istanbul changed his career—and his life,” Yale Review, 12 June 2023Chaim Jakov Gelfand, “A Jewish Socialist Critique of Zionism, from 1906,” Verso Blog, 5 July 2024Tyler Foggatt, “Look What Taylor Made Us Do,” New Yorker, 3 June 2023Andrew Peck, “Stephen Shore’s American Beauty.” Aperture, 1 August 2024Mary Overlie, “The Studies Project.” Contact Quarterly 9, 3 (1984): 30-37Randi Storch, “Maurice Isserman on His New Book, Reds,” Labor Online, 29 July 2024Len Gutkin, “Laura Kipnis’s Title IX Inquisition, a Decade Later,” Chronicle of Higher Education, 5 August 2024Nina Silber, “The History of Camp Wo-Chi-Ca,” History News Network, 6 August 2024Michael D. Hattem, “A Nation Is a Living Thing,” History News Network, 6 August 2024Katha Pollitt, “What’s Left After Wokeness?,” The Nation, 6 August 2024Joseph Stiglitz, “How Neoliberalism Failed, and What a Better Society Could Look Like,” Working Paper, Roosevelt Institute, 7 August 2024Claire Bishop, “The Disordering of Attention,” Verso Blog, 26 June 2024Emmaly Wiederholt, “Erin: Considering Sustainability,” Stance on Dance, 5 August 2024Charles J. Holden, “What Should We Remember About the 1960s?,” Los Angeles Review of Books, 8 August 2024Corey Kilgannon, “A Jazz DJ’s Lifetime of Knowledge Leaves Queens for a New Nashville Home,” New York Times, 11 August 2024Charlotte Rosen, “Public Thinker: Jonathan Kramnick on the Craft of Criticism amid Institutional Decline.” Public Books, 8 August 2024Anne-Laure Tissut and George Kowalik.,“Symptoms of American Deficiency: An Interview with Percival Everett,” ASAP Journal, 12 August 2024Imani Radney, “What Is the Infrastructure of Critique?,” Public Books, 13 August 2024April Ledbetter, “Our Sonic Environment: Adventures in Ecoacoustics and the Tuning of the World,” Dust to Digital Substack, 21 August 2024Henry Ferrell, “Illiberalism is not the cure for neoliberalism: Democrats should be reading Danielle Allen, not Deneen,” Programmable Mutter, 21 August 2024Benjamin Kunkel, “The Intractable Puzzle of Growth,” The Nation, August 26, 2024Sarah Dunstan and Patricia Owens, “Claudia Jones, International Thinker,” Modern Intellectual History 19, 2 (June 2022): 551–74Marina Magloire, “Moving Towards Life,” Los Angeles Review of Books, 7 August 2024Gary G. Gibbs, James M. Ogier, Whitney A.M. Leeson, and Karen F. Harris, “On the Potential of Book Reviews,” Perspectives on History, 29 January 2024“Walls”

Traveling the Hudson River

@ New-York Historical Society

What Matters: A Proposition in Eight Rooms

@ SFMoMA

Trade Windings: De-Lineating the American Tropics

@ MCA ChicagoMaking Time @ Secrist BeachJason Rhoades, Drive @ Hauser & WirthSongs for Modern Japan: Popular Music and Graphic Design, 1900–1950 @ Museum of Fine Arts BostonOscar Murillo, The Flooded Garden @ Tate ModernRaqib Shaw, Ballads of East and West @ Museum of Fine Arts HoustonThomas Demand, The Stutter of History @ Museum of Fine Arts HoustonVanessa German @ Logan Center Exhibitions, Reva and David Logan Center for the ArtsJongsuk Yoon, Yellow May @ Marian Goodman GalleryTanya Lukin Linklater, Inner blades of grass (soft) inner blades of grass (cured) inner blades of grass (bruised by the weather) @ Wexner Center for the Arts

Multiplicity: Blackness in Contemporary American Collage

@ Phillips CollectionMatisse & Renoir: New Encounters @ Barnes FoundationAnselm Kiefer, Angeli caduti @ Fondazione Palazzo StrozziEnio Arroyo Gomez, From Argentina and Costa Rica to the Streets of Tribeca @ On the FringeLynda Benglis, Knots & Videotapes 1972–1976 @ Thomas Dane GalleryMary Heilmann, Daydream Nation @ Hauser & WirthWillem De Kooning and Italy @ Gallerie Dell’AccademiaFernando Palma Rodríguez, Āmantēcayōtl: And When it Disappears, it is Said, the Moon has Died (Auh inihcuac huel ompoliuh, mitoa, ommic in meztli) @ Canal ProjectsJulian Schnabel, Paintings from 1978–1987 @ Vito Schnabel GalleryRita Ackermann, Splits @ Hauser & WirthJonas N.T. Becker, A Hole is not a Void @ Wexner Center For The ArtsAmalia Mesa-Bains, Archaeology Of Memory @ El Museo Del BarrioTiff Massey, 7 Mile + Livernois @ Detroit Institute Of ArtsEd Ruscha, Now Then @ Los Angeles County Museum Of ArtJutta Koether, 1982, 1983, 1984 @ Galerie BuchholzArab Presences: Modern Art and Decolonisation Paris, 1908-1988 @ Musée D’Art ModernePetrit Halilaj, Abetare @ Metropolitan Museum of ArtJordan Loeppky-Kolesnik, Diurnal @ Art LotEva Hesse, Five Sculptures @ Hauser & WirthRosalie D. Gagné, A Contemporary Alchemist @ Neuberger Museum of ArtPeter Kennard, Archive of Dissent, Expanded @ Whitechapel GalleryWhitney Biennial 2024: Even Better than the Real Thing @ Whitney Museum of American ArtMarcus the Artist: City of Gold @ Logan Center for the Arts“Stages”Marc Ribot, performing to Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid @ Little Theater, 22 August 2024John Zorn & Michihiro Sato, Samurai Memory, 1985 @ Roulette TapesHamlet @ Delacorte Theater, Summer 2023Underdog: The Other Other Brontë, National Theater of EnglandDr. Michael D. Hattem, Fireside Chat – The Memory of ’76: The Revolution in American History @ Library Company of Philadelphia, 22 August 2024Body/Head, Performing with Jim Shaw’s Thinking the Unthinkable @ Gagosian Beverly Hills, 8 August 2024Punkfest Cornell—Communities and Identities @ Cornell Univesity, 5 November 2016Mavis Staples with Jeff Tweedy @ Stephen Colbert Show, Auditorium Theater, 23 August 2024ScreensMylo the Cat aka Adam Schleichkorn, Snoop Dogg | Who Am I (What’s My Name), Muppets VersionJoan Jonas: New York Performances, Art21, 2015Typhoon ClubI Like It HereThe Third ManThe StrangerThree Body Problem, Season 01

Charlie Chaplin and Jackie Coogan in The Kid, 1921.SoundsMoscow Notebooks, BBC SoundsSevern, BBC SoundsJoe Jones on UbuwebWorld Turned Upside Down, Season 01William Eggleston, Memphis, NTS Radio, 24 July 2023Norman Thomas discusses the book Great Dissenters, part 1, 11 November 1961, Studs Terkel Radio ArchiveNorman Thomas discusses the book Great Dissenters, part 2, with Lillian Smith, 11 November 1961, Studs Terkel Radio ArchiveIkue Mori, Robert Quine, Marc Ribot, Painted DesertMarion Brown, “Iditus”K.Z. Morogoro Jazz Band, “Nikupendeje”Louis Armstrong, “I Hope Gabriel Likes My Music”Louis Armstrong Orchestra, “Cain and Abel”Henry Flynt, Hillbilly Tape MusicEugene Chadbourne, *There’ll Be No Tears TonightBelle and Sebastian, “Everyday People”Arrested Development, “People Everyday”WordsClaire Messud, This Strange Eventful HistoryEd Park, Same Bed Different DreamsAaron Cometbus, Despite Everything: CometbusMark Davidson and Parker Fishel, Bob Dylan: Mixing Up the MedicineHunter Dukes, “Kojève & Cigarettes,” Cabinet, 29 August 2024Gabriel Winant, “We Can Breathe!,” London Review of Books, 1 August 2024Joshua P. Hill, “Late Capitalism Turns to Fascism: The rich are looking for a bailout,” New Means, 11 July 2024K. Sabeel Rahman, “Building the Government We Need: A Framework for Democratic State Capacity,” Roosevelt Institute, 6 June 2024Evgeny Morozov, “Can AI Break Out of Panglossian Neoliberalism?,” Boston Review, 31 July 2024Wesley Morris, “Meshell Ndegeocello Could Have Had Stardom but Chose Music Instead,” New York Times, 1 August 2024Shalon van Tine, “A Failure of Vision,” CounterPunch, 13 March 2022Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi, “James Baldwin in Turkey: How Istanbul changed his career—and his life,” Yale Review, 12 June 2023Chaim Jakov Gelfand, “A Jewish Socialist Critique of Zionism, from 1906,” Verso Blog, 5 July 2024Tyler Foggatt, “Look What Taylor Made Us Do,” New Yorker, 3 June 2023Andrew Peck, “Stephen Shore’s American Beauty.” Aperture, 1 August 2024Mary Overlie, “The Studies Project.” Contact Quarterly 9, 3 (1984): 30-37Randi Storch, “Maurice Isserman on His New Book, Reds,” Labor Online, 29 July 2024Len Gutkin, “Laura Kipnis’s Title IX Inquisition, a Decade Later,” Chronicle of Higher Education, 5 August 2024Nina Silber, “The History of Camp Wo-Chi-Ca,” History News Network, 6 August 2024Michael D. Hattem, “A Nation Is a Living Thing,” History News Network, 6 August 2024Katha Pollitt, “What’s Left After Wokeness?,” The Nation, 6 August 2024Joseph Stiglitz, “How Neoliberalism Failed, and What a Better Society Could Look Like,” Working Paper, Roosevelt Institute, 7 August 2024Claire Bishop, “The Disordering of Attention,” Verso Blog, 26 June 2024Emmaly Wiederholt, “Erin: Considering Sustainability,” Stance on Dance, 5 August 2024Charles J. Holden, “What Should We Remember About the 1960s?,” Los Angeles Review of Books, 8 August 2024Corey Kilgannon, “A Jazz DJ’s Lifetime of Knowledge Leaves Queens for a New Nashville Home,” New York Times, 11 August 2024Charlotte Rosen, “Public Thinker: Jonathan Kramnick on the Craft of Criticism amid Institutional Decline.” Public Books, 8 August 2024Anne-Laure Tissut and George Kowalik.,“Symptoms of American Deficiency: An Interview with Percival Everett,” ASAP Journal, 12 August 2024Imani Radney, “What Is the Infrastructure of Critique?,” Public Books, 13 August 2024April Ledbetter, “Our Sonic Environment: Adventures in Ecoacoustics and the Tuning of the World,” Dust to Digital Substack, 21 August 2024Henry Ferrell, “Illiberalism is not the cure for neoliberalism: Democrats should be reading Danielle Allen, not Deneen,” Programmable Mutter, 21 August 2024Benjamin Kunkel, “The Intractable Puzzle of Growth,” The Nation, August 26, 2024Sarah Dunstan and Patricia Owens, “Claudia Jones, International Thinker,” Modern Intellectual History 19, 2 (June 2022): 551–74Marina Magloire, “Moving Towards Life,” Los Angeles Review of Books, 7 August 2024Gary G. Gibbs, James M. Ogier, Whitney A.M. Leeson, and Karen F. Harris, “On the Potential of Book Reviews,” Perspectives on History, 29 January 2024“Walls”

Traveling the Hudson River

@ New-York Historical Society

What Matters: A Proposition in Eight Rooms

@ SFMoMA

Trade Windings: De-Lineating the American Tropics

@ MCA ChicagoMaking Time @ Secrist BeachJason Rhoades, Drive @ Hauser & WirthSongs for Modern Japan: Popular Music and Graphic Design, 1900–1950 @ Museum of Fine Arts BostonOscar Murillo, The Flooded Garden @ Tate ModernRaqib Shaw, Ballads of East and West @ Museum of Fine Arts HoustonThomas Demand, The Stutter of History @ Museum of Fine Arts HoustonVanessa German @ Logan Center Exhibitions, Reva and David Logan Center for the ArtsJongsuk Yoon, Yellow May @ Marian Goodman GalleryTanya Lukin Linklater, Inner blades of grass (soft) inner blades of grass (cured) inner blades of grass (bruised by the weather) @ Wexner Center for the Arts

Multiplicity: Blackness in Contemporary American Collage

@ Phillips CollectionMatisse & Renoir: New Encounters @ Barnes FoundationAnselm Kiefer, Angeli caduti @ Fondazione Palazzo StrozziEnio Arroyo Gomez, From Argentina and Costa Rica to the Streets of Tribeca @ On the FringeLynda Benglis, Knots & Videotapes 1972–1976 @ Thomas Dane GalleryMary Heilmann, Daydream Nation @ Hauser & WirthWillem De Kooning and Italy @ Gallerie Dell’AccademiaFernando Palma Rodríguez, Āmantēcayōtl: And When it Disappears, it is Said, the Moon has Died (Auh inihcuac huel ompoliuh, mitoa, ommic in meztli) @ Canal ProjectsJulian Schnabel, Paintings from 1978–1987 @ Vito Schnabel GalleryRita Ackermann, Splits @ Hauser & WirthJonas N.T. Becker, A Hole is not a Void @ Wexner Center For The ArtsAmalia Mesa-Bains, Archaeology Of Memory @ El Museo Del BarrioTiff Massey, 7 Mile + Livernois @ Detroit Institute Of ArtsEd Ruscha, Now Then @ Los Angeles County Museum Of ArtJutta Koether, 1982, 1983, 1984 @ Galerie BuchholzArab Presences: Modern Art and Decolonisation Paris, 1908-1988 @ Musée D’Art ModernePetrit Halilaj, Abetare @ Metropolitan Museum of ArtJordan Loeppky-Kolesnik, Diurnal @ Art LotEva Hesse, Five Sculptures @ Hauser & WirthRosalie D. Gagné, A Contemporary Alchemist @ Neuberger Museum of ArtPeter Kennard, Archive of Dissent, Expanded @ Whitechapel GalleryWhitney Biennial 2024: Even Better than the Real Thing @ Whitney Museum of American ArtMarcus the Artist: City of Gold @ Logan Center for the Arts“Stages”Marc Ribot, performing to Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid @ Little Theater, 22 August 2024John Zorn & Michihiro Sato, Samurai Memory, 1985 @ Roulette TapesHamlet @ Delacorte Theater, Summer 2023Underdog: The Other Other Brontë, National Theater of EnglandDr. Michael D. Hattem, Fireside Chat – The Memory of ’76: The Revolution in American History @ Library Company of Philadelphia, 22 August 2024Body/Head, Performing with Jim Shaw’s Thinking the Unthinkable @ Gagosian Beverly Hills, 8 August 2024Punkfest Cornell—Communities and Identities @ Cornell Univesity, 5 November 2016Mavis Staples with Jeff Tweedy @ Stephen Colbert Show, Auditorium Theater, 23 August 2024ScreensMylo the Cat aka Adam Schleichkorn, Snoop Dogg | Who Am I (What’s My Name), Muppets VersionJoan Jonas: New York Performances, Art21, 2015Typhoon ClubI Like It HereThe Third ManThe StrangerThree Body Problem, Season 01