Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 7

August 24, 2024

2024 October 22—Music & Protest in Historical Perspective

August 19, 2024

Syllabus—The American Mind

Faith Ringgold,The American People Series #18: The Flag is Bleeding, 1967.Instructor info

Faith Ringgold,The American People Series #18: The Flag is Bleeding, 1967.Instructor infoDr. Michael J. Kramer, Department of History, SUNY Brockport, mkramer@brockport.edu

Who is your instructor?Michael J. Kramer specializes in modern US cultural and intellectual history, transnational history, public and digital history, and cultural criticism. He is an associate professor of history at the State University of New York (SUNY) Brockport, the author of The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture (Oxford University Press, 2013), and the director of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project. He is currently working on a history of the 1976 United States bicentennial celebration and a study of folk music, technology, and cultural democracy in the United States. He edits The Carryall, an online journal of US cultural and intellectual history and maintains a blog of cultural criticism, Culture Rover. His website, with additional information about publications, projects, courses, talks, and more can be found at michaeljkramer.net.

What are we up to?In this course, students read, write, and discuss topics and themes in US intellectual history as we explore a diversity of past voices that remain relevant today. Then students put their knowledge to work through focused digital scholarly editorial contributions to The Carryall, an online journal of US cultural and intellectual history based right here at SUNY Brockport and edited by Dr. Kramer. A core question framing this seminar is whether there such a thing as one “American Mind” or if, in fact, there are many American minds? Who gets to decide? On what grounds? Combining an introduction to intellectual history as a subfield of historical inquiry with professional development, research, and experiential learning in digital scholarly editing, the course helps students learn about how people thought back then and how, in today’s digital age, you might think about the world now.

What do we do in this course? We read. We read some more. We discuss. We compare. We contrast. We ask questions and try to come up with some responses to those answers. And then we read some more and discuss some more. We work on writing, editing, and research skills. We develop basic DIY (Do It Yourself) project management chops and hack our way toward basic digital skills. We probe how Americans have thought about themselves and their worlds. We also, in this upper-level seminar, extensively explore the “historiography” (fancy way of saying the study of history) of how Americans have thought about themselves and their worlds. We ask how ideas, thinking, intellectual life, something called “ideology, the imagination, and the “ideational” have related—and continue to relate—to other historical factors: social organization, politics and power, the law, economics, cultural and artistic expression in both textual and other forms, with regard to physical bodies, physicality, medicine, and science, national formations, international relations, local and community life, global dynamics, senses of time, definitions of eras, chronologies, and spatial and geographic configurations. Overall, this course lets you think better—more clearly, more precisely, more deeply—about thinking itself in the United States as we connect big, abstract ideas and concepts to the very practical matter of how to sustain an online journal of cultural and intellectual history.

This term we will be working extensively with readings in secondary literatures of US intellectual history, then we will turn to primary sources ourselves and begin to read, analyze, tag, and describe a set of readings in intellectual history for a digital database being developed at The Carryall. All students write for the course as a mode of thinking through ideas and observations more carefully and improving historical thinking and communication skills. Students have the option of designing an audio podcast about a particular US intellectual or idea. Graduate students will develop one longer final essay for the course (swing course HST409/509) 3 Cr. Fall.

Required materialsJennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, The Ideas That Made America: A Brief History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019)Daniel Wickberg, A History of American Thought 1860-2000: Thinking the Modern (New York, NY: Routledge, 2024)Additional essays, readings, films, and multimedia materials on course websiteAt Library Reserves and on Brightspace:David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper, eds., The American Intellectual Tradition, Volume I: 1630 to 1865 and Volume II: 1865 to the Present (we will be using various editions of the books)Meetings and readingsThe instructor may adjust the meetings schedule as needed during the term, but will give clear instructions about any changes.

UNIT 01: What Is US intellectual history, anyway?Week 01Tu, 08/27: Introductions

Th, 08/29: What Is US intellectual history, anyway?

Required:

Peter Gordon, “What is Intellectual History? A frankly partisan introduction to a frequently misunderstood field,” unpublished manuscript, 2012, on BrightspaceWeek 02Tu, 09/03: What Is US intellectual history, anyway?

Required:

Peter Gordon, “What is Intellectual History? A frankly partisan introduction to a frequently misunderstood field,” unpublished manuscript, 2012, on BrightspaceJennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, “Introduction,” The Ideas That Made America: A Brief History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019)Th, 09/05: What Is US intellectual history, anyway?

Required:

Peter Gordon, “What is Intellectual History? A frankly partisan introduction to a frequently misunderstood field,” unpublished manuscript, 2012, on BrightspaceJennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, “Introduction,” The Ideas That Made America: A Brief History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019)Daniel Wickberg, “Introduction,” A History of American Thought 1860-2000: Thinking the Modern (New York, NY: Routledge, 2024)Week 03Tu, 09/10: What Is US intellectual history, anyway?

Required:

John Higham, “The Rise of American Intellectual History,” The American Historical Review 56, 3 (1951): 453–71, or on BrightspaceJohn Hingham, “Introduction,” in New Directions in American Intellectual History, eds. John Higham and Paul K. Conkin (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979), xi-xvii, on BrightspaceLaurence Veysey, “Definitions: Intellectual history and the new social history,” in New Directions in American Intellectual History, 3-26 on BrightspaceGordon S. Wood, “Intellectual history and the social sciences,” 27-41, in New Directions in American Intellectual History, on BrightspaceDavid A. Hollinger, “Historians and the discourse of intellectuals,” in New Directions in American Intellectual History, 42-63, on BrightspaceRush Welter, “On studying the national mind,” in New Directions in American Intellectual History, 64-84, on BrightspaceTh, 09/12: What Is US intellectual history, anyway?

Required:

Daniel Wickberg, “Is Intellectual History a Neglected Field of Study?” Historically Speaking 10, no. 4 (2009): 14–17, or on BrightspaceDavid A. Hollinger, “Thinking Is as American as Apple Pie,” Historically Speaking 10, no. 4 (2009): 17–18, or on BrightspaceSarah E. Igo, “Reply to Daniel Wickberg,” Historically Speaking 10, no. 4 (2009): 19–20, or on BrightspaceWilfred M. McClay, “Response to Daniel Wickberg,” Historically Speaking 10, no. 4 (2009): 20–22, or on BrightspaceDaniel Wickberg, “Rejoinder to Hollinger, Igo, and McClay,” Historically Speaking 10, no. 4 (2009): 22–24, or on BrightspaceWeek 04Tu, 09/17: What Is US intellectual history, anyway?

Required:

Thomas Bender, “Forum: The Present and Future of American Intellectual History Introduction.” Modern Intellectual History 9, no. 1 (April 2012): 149–56, or on BrightspaceLeslie Butler, “From the History of Ideas to Ideas in History.” Modern Intellectual History 9, no. 1 (April 2012): 157–69, or on BrightspaceDavid D. Hall, “Backwards to the Future: The Cultural Turn and the Wisdom of Intellectual History.” Modern Intellectual History 9, no. 1 (April 2012): 171–84, or on BrightspaceDavid A. Hollinger, “What Is Our ‘Canon’? How American Intellectual Historians Debate the Core of Their Field.” Modern Intellectual History 9, no. 1 (April 2012): 185–200, or on BrightspaceJames T. Kloppenberg, “Thinking Historically: A Manifesto of Pragmatic Hermeneutics.” Modern Intellectual History 9, no. 1 (April 2012): 201–16, or on BrightspaceJeffrey Sklansky, “The Elusive Sovereign: New Intellectual and Social Histories of Capitalism.” Modern Intellectual History 9, no. 1 (April 2012): 233–48, or on BrightspaceAngus Burgin, “The ‘Futures’ of American Intellectual History,” Society for US Intellectual History Blog, 21 October 2013, or on BrightspaceMichael J. Kramer, “The State of Intellectual History,” Society for US Intellectual History Blog, 26 May 2019Th, 09/19: What Is US cultural history, anyway?

Required:

James Cook and Lawrence Glickman, “Twelve Propositions for a History of US Cultural History,” in Cook, James W. Cook, Lawrence B. Glickman, and Michael O’Malley, The Cultural Turn in U.S. History: Past, Present, and Future, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 3-57, on BrightspaceWeek 05 — Surveying US intellectual historyTu, 09/24: Beginnings

Required:

Ratner-Rosenhagen, The Ideas That Made America, Introduction, Ch 1, Ch 2, 1-50Th, 09/26: Middles

Required:

Ratner-Rosenhagen, Ch 3, Ch 4, 51-96Week 06 — Surveying US intellectual historyTu, 10/01: Modernity

Required:

Ratner-Rosenhagen, Ch 5, Ch 6, Ch 7, 97-151Th, 10/03: Postmodernity?

Required:

Ratner-Rosenhagen, Ch 8, Epilogue, 152-180Week 07 — More recent historiographic interventionsTu, 10/08: African American intellectual history, All on Zoom

Required:

Brandon R. Byrd, “The Rise of African American Intellectual History,” Modern Intellectual History (2020), 1–32Optional:

“Brandon R. Byrd—Redefining Intellectual History,” Fields of the Future Podcast, 29 April 2021“Brandon R. Byrd on African American Intellectual History,” AHR Interview Podcast, 18 March 2019Th, 10/10: Women’s intellectual history, All on Zoom

Required:

Sophie Smith, “Women and Intellectual History in the Twentieth Century, Part One: Rethinking the ‘Origins’ of US Intellectual History,” Journal of the History of Ideas 85, no. 3 (2024): 425–54, or on BrightspaceHettie V. Williams and Melissa Ziobro, “Introduction,” A Seat at the Table: Black Women Public Intellectuals in US History and Culture (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2023), on BrightspaceCaroline Winterer, “Is There an Intellectual History of Early American Women?,” Modern Intellectual History 4, no. 1 (April 2007): 173–90, or on BrightspaceWeek 08 — Wickberg and primary sourcesTu, 10/15: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, A History of American Thought 1860-2000, IntroductionSelections from Hollinger and Capper, eds., The American Intellectual Tradition, Volumes I and IITh, 10/17: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, Ch 1Selections from AITWeek 09 — Wickberg and primary sourcesTu, 10/22: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, Ch 2-3Selections from AITTh, 10/24: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, Ch 4Selections from AITWeek 10 — Wickberg and primary sourcesTu, 10/29: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, Ch 5-6Selections from AITTh, 10/31: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, Ch 7Selections from AITWeek 11 — Wickberg and primary sourcesTu, 11/05: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, Ch 8-9Selections from AITTh, 11/07: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, Ch 10Selections from AITWeek 12 — Wickberg and primary sourcesTu, 11/12: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, Ch 11-12Selections from AITTh, 11/14: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, Ch 13Selections from AITWeek 13 — Wickberg and primary sourcesTu, 11/19: A History of American Thought 1860-2000

Required:

Wickberg, Ch 14-15Selections from AITTh, 11/21: Primary source analysis presentations

Week 14 — ThanksgivingNo Class

Optional: The Examined Life, dir. Astra Taylor (2006), on BrightspaceWeek 15 — ConclusionsTu, 12/03: Primary source analysis presentations

Th, 12/05: Conclusions and reflections

AssignmentsThe instructor may adjust the assignments schedule as needed during the term, but will give clear instructions about any changes.

DUE BY START OF WEEK 02 (Mo 09/02)—Student info formDUE WEEK 04 (Mo 09/16) 10%—What Is US intellectual history, anyway? Write a two-to-three page analysis using at least two of the documents we have read so far to develop your own understanding of US intellectual history.DUE WEEK 06 (Mo 09/30) 10%—Is there an “American Mind”? Write a two-to-three page analysis using at least three of the documents we have read so far to develop your own understanding of this question. If there is one American Mind, what is the best way to describe it; if not, how do we think about the idea of a national intellectual culture in the United States?; or, what other ways might we conceptualize US intellectual history?DUE WEEK 08 (Mo 10/14) 20%—Surveying US intellectual history: Select a chapter from The Ideas That Made America to analyze in two-to-three pages. What is the argument of the chapter in relation to the broader argument of the book? Do you agree or disagree? How else might you present the analysis in that chapter? Use primary sources from Hollinger and Capper, eds., The American Intellectual Tradition to shape your commentary on the chapter.DUE END OF COURSE (Mo 12/14) 15%—Primary Source Database Development AssignmentDUE END OF COURSE (Mo 12/14) 25%—Write a close analysis of the primary source or sources with which you are working in relation to Wickberg’s arguments. 4-to-5 pages undergraduates in 409. 6-8 pages MA students in 509.OPTIONAL DUE END OF COURSE (Mo 12/14) Extra credit—Develop an audio podcast about your primary source.DUE END OF COURSE (Mo 12/14) 20%—Attendance, In-Class Worksheets, and Participation. Please note attendance policy below: you may miss up to four class meetings no questions asked, with or without a justified reason (this includes sports team travel, illness, or other reasons). You do not need to notify the instructor of your absences.EvaluationThis course uses a simple evaluation process to help you improve your understanding of both US history since the Civil War and history as a method. Note that evaluations are never a judgment of you as a person; rather, they are meant to help you assess how you are processing material in the course and how you can keep improving college-level and lifelong skills of historical knowledge and skills. Remember that history is a craft and it takes practice and iteration to improve, as with any knowledge and skill you wish to develop; but, if you keep at it, thinking historically can help you understand the complexities of the world more powerfully.

There are four evaluations given for assignments—(1) Yes!; (2) Getting Closer; (3) Needs Work; (4) Nah—plus comments, when relevant, based on the rubric below. Late assignments will lose one grade per each day they are late.

Remember to honor the Academic Honesty Policy at SUNY Brockport, including no plagiarism. In this course there is no need to use sources outside of the required ones for the class. The instructor recommends not using algorithmic software such as ChatGPT for your assignments, but rather working on your own writing skills. If you do use algorithmic software, you must cite it as you would any other secondary source that is not your own.

Overall course rubricYes! = A-level work. These show evidence of:

clear, compelling writing assignments that include:a credible, persuasive argument with some originalityargument persuasively supported by relevant, accurate and complete evidencepersuasive integration of argument and evidence in an insightful analysisexcellent organization: introduction, topic sentences, coherent paragraphs, use of evidence, contextualization, analysis, smooth transitions, conclusionprose free of spelling and grammatical errors with lack of clichéscorrect page formatting when relevant, with regular margins, 12-point font, double spacedaccurate formatting of footnotes and bibliography with required citation and documentationon-time submission of assignmentsYour essay should include (as per Joel M. Sipress, “Why Students Don’t Get Evidence and What We Can Do About It,”The History Teacher, 37, 3, May 2004, or on Brightspace):Thesis—The “thesis” is the point that you are trying to prove. It is the thing of which you are trying to persuade the audience. It is your answer to the important question. A good thesis can usually be expressed in a sentence or two. The ability to formulate a clear and concise thesis is the fundamental skill of argumentation. One cannot argue effectively for a position unless it is clear what that position is.Summary—Arguments often take the form of a response to another person’s argument. In order to respond effectively to an argument, one must first be able to effectively identify and summarize that other person’s argument, including the other person’s thesis.Organization—In order to demonstrate a thesis, one must present points in support of that thesis. The persuasiveness of the argument depends largely upon the organization with which one presents the supporting points. The key to a well-organized argument is to present the supporting points one at a time in a logical order.Evidence—The fundamental criteria by which the persuasiveness of an argument should be judged is the degree to which specific evidence is provided that demonstrates the thesis and supporting points. The ability to locate and present such evidence is thus a fundamental skill of argumentation.Your essay should generally try to engage at least one, if not more than one, of the “5 C’s” as described in Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke. “What Does It Mean to Think Historically?,” Perspectives on History, January 2007. These are:Change over timeContextCausalityContingencyComplexityfor class meetings, regular attendance and timely preparation overall, plus insightful, constructive, respectful, and regular participation in class discussionsoverall, a thorough understanding of required course materialGetting Closer = B-level work, It is good, but with minor problems in one or more areas that need improvement.

Needs work = C-level work is acceptable, but with major problems in several areas or a major problem in one area.

Nah = D-level work. It shows major problems in multiple areas, including missing or late assignments, missed class meetings, and other shortcomings.

E-level work is unacceptable. It fails to meet basic course requirements and/or standards of academic integrity/honesty.

Successful assignments demonstrate:

Argument – presence of an articulated, precise, compelling argument in response to assignment prompt; makes an evidence-based claim and expresses the significance of that claim; places argument in framework of existing interpretations and shows distinctive, nuanced perspective of argument. Your argument should engage at least one of the “how to think historically” categories: Change over time; context; causality; contingency; complexity. From Joel Sipress: Thesis—The “thesis” is the point that you are trying to prove. It is the thing of which you are trying to persuade the audience. It is your answer to the important question. A good thesis can usually be expressed in a sentence or two. The ability to formulate a clear and concise thesis is the fundamental skill of argumentation. One cannot argue effectively for a position unless it is clear what that position is.Evidence – presence of specific evidence from primary sources to support the argument. From Joel Sipress: Evidence—The fundamental criteria by which the persuasiveness of an argument should be judged is the degree to which specific evidence is provided that demonstrates the thesis and supporting points. The ability to locate and present such evidence is thus a fundamental skill of argumentation.Argumentation – presence of convincing, compelling connections between evidence and argument; effective explanation of the evidence that links specific details to larger argument and its sub-arguments with logic and precisionContextualization – presence of contextualization, which is to say an accurate portrayal of historical contexts in which evidence appeared and argument is being made. From Joel Sipress: Summary—Arguments often take the form of a response to another person’s argument. In order to respond effectively to an argument, one must first be able to effectively identify and summarize that other person’s argument, including the other person’s thesis.Citation – wields Chicago Manual of Style citation standards effectively to document use of primary and secondary sourcesOrganization and Style – presence of logical flow of reasoning and grace of prose, including:an effective introduction that hooks the reader with originality and states the argument of the assignment and its significanceclear topic sentences that provide sub-arguments and their significance in relation to the overall argumenteffective transitions between paragraphsa compelling conclusion that restates argument and adds a final pointaccurate phrasing and word choiceuse of active rather than passive voice sentence constructionsFrom Joel Sipress: Organization—In order to demonstrate a thesis, one must present points in support of that thesis. The persuasiveness of the argument depends largely upon the organization with which one presents the supporting points. The key to a well-organized argument is to present the supporting points one at a time in a logical order.Citation and style guide: Using Chicago Manual of StyleThere is a nice overview of citation at the Chicago Manual of Style websiteFor additional, helpful guidelines, visit the Drake Memorial Library’s Chicago Manual of Style pageYou can always go right to the source: the 17th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style is available for reference at the Drake Memorial Library Reserve DeskWriting consultationWriting Tutoring is available through the Academic Success Center. It will help at any stage of writing. Be sure to show your tutor the assignment prompt and syllabus guidelines to help them help you.

Research consultationThe librarians at Drake Memorial Library are an incredible resource. You can consult with them remotely or in person. To schedule a meeting, go to the front desk at Drake Library or visit the library website’s Consultation page.

Attendance policyYou will certainly do better with evaluation in the course, learn more, and get more out of the class the more you attend meetings, participate in discussions, complete readings, and finish assignments. That said, lives get complicated. Therefore, you may miss up to four class meetings, with or without a justified reason (this includes sports team travel, illness, or other reasons). You do not need to notify the instructor of your absences.

If you are ill, please stay home and take precautions if you have any covid or flu symptoms. Moreover, masks are welcome in class if you are still recovering from illness or feel sick.After six absences, subsequent absences will result in reduction of final course grade at the discretion of the instructor. Generally, more than five absences results in the loss of one grade per additional absences from final course evaluation.

Disabilities and accommodationsIn accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and Brockport Faculty Senate legislation, students with documented disabilities may be entitled to specific accommodations. SUNY Brockport is committed to fostering an optimal learning environment by applying current principles and practices of equity, diversity, and inclusion. If you are a student with a disability and want to utilize academic accommodations, you must register with Student Accessibility Services (SAS) to obtain an official accommodation letter which must be submitted to faculty for accommodation implementation. If you think you have a disability, you may want to meet with SAS to learn about related resources. You can find out more about Student Accessibility Services or by contacting SAS via the email address sasoffice@brockport.edu or phone number (585) 395-5409. Students, faculty, staff, and SAS work together to create an inclusive learning environment. Feel free to contact the instructor with any questions.

Discrimination and harassment policiesSex and Gender discrimination, including sexual harassment, are prohibited in educational programs and activities, including classes. Title IX legislation and College policy require the College to provide sex and gender equity in all areas of campus life. If you or someone you know has experienced sex or gender discrimination (including gender identity or non-conformity), discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or pregnancy, sexual harassment, sexual assault, intimate partner violence, or stalking, we encourage you to seek assistance and to report the incident through these resources. Confidential assistance is available on campus at Hazen Center for Integrated Care. Another resource is RESTORE. Note that by law faculty are mandatory reporters and cannot maintain confidentiality under Title IX; they will need to share information with the Title IX & College Compliance Officer.

Statement of equity and open communicationWe recognize that each class we teach is composed of diverse populations and are aware of and attentive to inequities of experience based on social identities including but not limited to race, class, assigned gender, gender identity, sexuality, geographical background, language background, religion, disability, age, and nationality. This classroom operates on a model of equity and partnership, in which we expect and appreciate diverse perspectives and ideas and encourage spirited but respectful debate and dialogue. If anyone is experiencing exclusion, intentional or unintentional aggression, silencing, or any other form of oppression, please communicate with me and we will work with each other and with SUNY Brockport resources to address these serious problems.

Disruptive student behaviorsPlease see SUNY Brockport’s procedures for dealing with students who are disruptive in class.

Emergency alert systemIn case of emergency, the Emergency Alert System at The College at Brockport will be activated. Students are encouraged to maintain updated contact information using the link on the College’s Emergency Information website.

Learning goalsThe study of history is essential. By exploring how our world came to be, the study of history fosters the critical knowledge, breadth of perspective, intellectual growth, and communication and problem-solving skills that will help you lead purposeful lives, exercise responsible citizenship, and achieve career success. History Department learning goals include:

Articulate a historical question and thesis in response to it through analysis of empirical evidenceAdvance in logical sequence principal arguments in defense of a historical thesisProvide relevant evidence drawn from the evaluation of primary and/or secondary sources that supports the primary arguments in defense of a historical thesisEvaluate the significance of a historical thesis by relating it to a broader field of historical knowledgeExpress themselves clearly in writing that forwards a historical analysis.Use disciplinary standards (Chicago Manual of Style) of documentation and citation when referencing historical sourcesIdentify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they appear in their own and others’ workDemonstrate understanding of the methods historians use to explore social phenomena, including observation, hypothesis development, measurement and data collection, experimentation, evaluation of evidence, and employment of interpretive analysisDemonstrate knowledge of major concepts, models and issues of US history since the Civil WarDevelop proficiency in oral discourse through class participation and discussionSyllabus—Modern America

Instructor Info

Instructor InfoDr. Michael J. Kramer, Department of History, SUNY Brockport, mkramer@brockport.edu.

Who is your instructor?Michael J. Kramer specializes in modern US cultural and intellectual history, transnational history, public and digital history, and cultural criticism. He is an associate professor of history at the State University of New York (SUNY) Brockport, the author of The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture (Oxford University Press, 2013), and the director of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project. He is currently working on a history of the 1976 United States bicentennial celebration and a study of folk music, technology, and cultural democracy in the United States. He edits The Carryall, an online journal of US cultural and intellectual history and maintains a blog of cultural criticism, Culture Rover. His website, with additional information about publications, projects, courses, talks, and more can be found at michaeljkramer.net.

What are we up to?You may think of history simply as the memorization of names and dates, and sure, we need to do some of that, but the study of history is really something far more intriguing. History asks us to figure out a seemingly simple question that gets complicated real fast, namely, how did we get here? This is the core question at stake in historical study. In our case, we will ask how we might better understand the development of the United States from the Civil War’s end in 1865 to our own times. What has changed in this duration of time, in this particular place? What continuities and themes do we notice? What caused what to happen—and, more complexly, why? History is about navigating all these questions, and other questions too, such as: whose history, exactly, do we wish to track? The rich and powerful? The everyday person? And why do we study history as we do, dividing it up by nations rather than other categories? How do all the elements of the past relate to each other, anyway? How do politics, economics, culture, ideas, beliefs, values, customs, environments, technologies, and social relationships connect, just to name a few aspects of the past?

Phew, lots of questions! Fortunately, history offers a method for navigating the messy, vast past as we try to not just memorize, but also give it some meaning. Which is to say history is more than just the feel-good myths we tell about America as a nation. History is more than just your opinion or what you feel. Instead, history is a multifaceted and multiperspectival set of stories we tell using empirical evidence or data to ask questions and come up with interpretations in dialogue with what others have had to say about the past. It is neither about one definitive truth, nor is it about anything goes. Instead it is about measuring and assessing a complex world with as much sophistication as we can muster. Sometimes the answers are simple; sometimes the evidence only produces more questions. History is made to handle both situations, which is why it can help you not only understand the past better, but also understand your own life more profoundly, and even, maybe, navigate your future with more dexterity, skill, and power. History is not a formula. It’s a craft for thinking about facts and truths and their many implications, connections, contexts, meanings, and mysteries.

So where do we start? First and foremost, history is about learning the craft of wielding evidence. We call the evidence our “sources.” They include artifacts of various types and kinds: documents, images, sounds, films, music, speeches, interviews, architecture, art, memories, and anything we can use to access the past. Questions come from what your close reading of the evidence suggests: what specific aspect of the evidence makes an impression on you? How can you put it in context with other bits of evidence to begin to paint a picture of the past? What questions does your close attention to the sources raise? What have other historians and people had to say about the topic at hand (a fancy word for this is “historiography”)? And what kind of convincing interpretation can you draw out of the sources and the existing interpretations of them to help us understand what happened more clearly and precisely?

How did we get here? Remember that this is the core question of history. And remember that the discipline offers a method you can learn to try to answer that question adequately. History, however, is not a science, not in the “natural” sciences sense. There is not usually one true answer (sometimes). The goal is not to achieve reproducible results or falsifiable claims (sometimes) as in the conventional scientific method. Yet history is more than just your opinion. It is based on empirical data. Instead of being reductive, it offers a method for handling complexity. In historical inquiry, there are a multiplicity of interpretations to consider, measure, grapple with, discuss, debate, and decide upon based on the empirical record (again, not your opinion, but your convincing interpretation and explanation of evidence).

So, in this course, we will learn what it means to practice the historical method as we explore the particular histories of the United States since the end of the Civil War in 1865. How did we get from that moment in time to now? What has changed? What continuities and themes have persisted? What kinds of interpretations and stories can we tell not based on what we want to believe or hope to believe or wish to believe about the United States, but rather based on the evidence?Through multimedia lectures, in-class assignments and discussions, at-home readings, writing assignments, and online assignments, you will learn more about what it means to study history, what it means to acquire the skills and capacities of thinking about the past and communicating your ideas about its sources and evidence more effectively. In doing so, you will not only leave this course with a better sense of the history of the United States over the last century and a half, but also with a better sense of how history can help you in whatever you wish to study, analyze, judge, or communicate to others when life gets complex. Sometimes the answers are simple, but as you grow older, you will see that most of the time they are not. Fortunately, history is here to help. For the skills of history are the very skills you will need not only to understand from where we have come, but also where you might want to go next.

Things you are expected to do this termBy taking this course you are agreeing to do the following to the best of your abilities:

Complete the readingsCome to class preparedParticipate in discussions in classComplete the assignments, using resources on campus such as the Academic Success Center and Drake Memorial Library to improve your research and writing skillsLearn how to use Microsoft Word to format essaysLearn how to cite evidence and sources accurately using Chicago Manual of StyleBe respectful of yourself, your instructor, and your fellow studentsRequired booksEric Foner, et. al., Give Me Liberty! Volume II Brief 7th Edition (WW Norton, 2023)Eric Foner, et. al., Voices of Freedom Volume II, 7th Edition (New York: WW Norton, 2023)Available at Brockport BookstoreI strongly recommend purchasing the online version of the book, but you can also purchase the new print version and then use the registration card to access the required online quizzes (sometimes for a small fee). Avoid the used print version because you will need to purchase access to the online version of the book anyway to access the required online tools (I don’t control these options, sorry!)Additional assigned documents and resources on Brightspace course websiteScheduleThe instructor may adjust the schedule as needed during the term, but will give clear instructions about any changes.

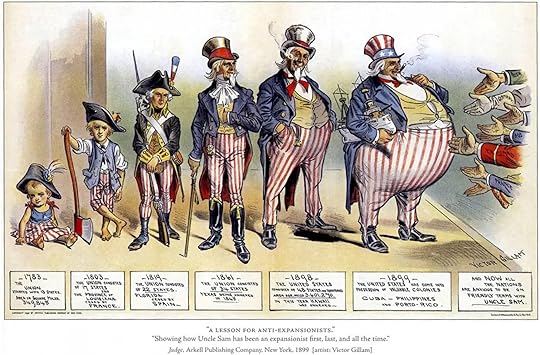

1865-1898Week 01 — Did the Civil War Ever End? The Reconstruction EraWeek 02 — What is the Study of History, Anyway? Learning About Historical Methods of InquiryWeek 03 — Industrialization: Not Just Bigger, But Different1898-1929Week 04 — Expansion: From Settler Colonialism to Formal ColonialismWeek 05 — What was the Progress in Progressivism? The Progressive Era, World War I, and Its AftermathWeek 06 —The Roaring Twenties: Roars of Modernity and AntimodernityResearch WeekWeek 07 — Drake Library Week1929-1969Week 08 — From Classic to Modern Liberalism: The Great Depression and the New DealWeek 09 — Did World War II Ever End? Mobilization, WWII, the Cold WarWeek 10 — The Fifties: Containments and RebellionsWeek 11 — Naming the System and Claiming Rights in the Sixties: Vietnam, Civil Rights, Social Movements, Backlash1969-2001Week 12 — Resignations and Demolitions: The Seventies — Living in a Material World: The EightiesWeek 13 — The End of the Cold War and the Rise of Neoliberalism: The Nineties2001-2024Week 14 — Thanksgiving Week 15 — Making America Great Again? Recent US History in Historical ContextReadings1865-1898Week 01 — Did the Civil War Ever End? The Reconstruction EraGive Me Liberty!, Preface, xxiv-xxxviiGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 15, What Is Freedom?: Reconstruction, 1865-1877,” 441-474Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 28, A Divided Nation, 887-933Voices of Freedom, Ch. 15, 1-27Martin Pengelly, “A disputed election, a constitutional crisis, polarisation…welcome to 1876” (interview with Eric Foner), The Guardian, 23 August 2020Optional: Kevin M. Levin, “How Slavery Almost Didn’t End in 1865,” Civil War Memory, 6 December 2022Optional: 1865 Podcast (historical fictional)Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: John Daly, “The Southern Civil War 1865-1877: When Did the Civil War End?,” on BrightspaceWeek 02 — What is the Study of History, Anyway? Learning About Historical Methods of InquiryThomas Andrews and Flannery Burke. “What Does It Mean to Think Historically?,” Perspectives on History, January 2007Joel M. Sipress, “Why Students Don’t Get Evidence and What We Can Do About It,” The History Teacher 37, 3 (2004), 351-363Optional: American Historical Association Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct (updated 2023)Week 03 — Industrialization: Not Just Bigger, But DifferentGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 16, America’s Gilded Age, 1870-1890, 475-511Voices of Freedom, Ch. 16, 28-55Joshua Specht, “The price of plenty: how beef changed America,” Guardian, 7 May 20191898-1929Week 04 — Expansion: From Settler Colonialism to Formal ColonialismGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 17, Freedom’s Boundaries, at Home and Abroad, 1890-1900, 512-545Voices of Freedom, Ch. 17, 56-77 Hopi Petition Asking for Title to Their Lands (1894), scroll down to read the transcription, especially p. 7Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94 (1884), Syllabus (full case optional if you are interested)Christine DeLucia, Doug Kiel, Katrina Phillips, and Kiara Vigil, “Histories of Indigenous Sovereignty in Action: What is it and Why Does it Matter?,” The American Historian, March 2021Week 05 — What was the Progress in Progressivism? The Progressive Era, World War I, and Its AftermathGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 18, The Progressive Era, 1900-1916, 546-577Voices of Freedom, Ch. 18, 78-106Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 19, Safe for Democracy: The United States and World War I, 1916-1920, 578-611Voices of Freedom, Ch. 19, 107-135Optional: Various Authors, “Suffrage at 100,” New York Times, 2019-2020Optional: Noam Maggor, “Tax Regimes: An interview with Robin Einhorn,” Phenomenal World, 24 March 2022Optional Brockport Faculty Listening: Elizabeth Garner Masarik, “100 Years of Woman Suffrage,” Dig! A History Podcast, 5 January 2020Week 06 —The Roaring Twenties: Roars of Modernity and AntimodernityGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 20, From Business Culture to Great Depression in the “Roaring” Twenties, 1920-1932, 612-642Voices of Freedom, Ch. 20, 136-163Research WeekWeek 07 — Drake Library Week1929-1969Week 08 — From Classic to Modern Liberalism: The Great Depression and the New DealGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 21: The New Deal, 1932-1940, 643- 675Voices of Freedom, Ch. 21, 164-190Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Anne S. Macpherson, “Birth of the U.S. Colonial Minimum Wage: The Struggle over the Fair Labor Standards Act in Puerto Rico, 1938– 1941,” Journal of American History 104, 3 (December 2017), 656-680, on BrightspaceWeek 09 — Did World War II Ever End? Mobilization, WWII, the Cold WarGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 22, Fighting for the Four Freedoms: World War II, 1941-1945, 676-711Voices of Freedom, Ch. 22, 191-212Give Me Liberty!, Ch. 23, The United States and the Cold War, 1945-1953, 712-740Voices of Freedom, Ch. 23, 213-245Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Bruce Leslie (and John Halsey), “A College Upon a Hill: Exceptionalism & American Higher Education,” in Marks of Distinction: American Exceptionalism Revisited, ed. Dale Carter (Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 2001), 197-228, on BrightspaceWeek 10 — The Fifties: Containments and RebellionsGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 24, An Affluent Society, 1953-1960, 741-772Voices of Freedom, Ch. 24, 246-269Week 11 — Naming the System and Claiming Rights in the Sixties: Vietnam, Civil Rights, Social Movements, BacklashGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 25, The Sixties, 1960-1968, 773-807Voices of Freedom, Ch. 25, 270-305Keisha N. Blain, “Fannie Lou Hamer’s Dauntless Fight for Black Americans’ Right to Vote,” Smithsonian Magazine, 20 August 2020Freedom’s Ring: King’s “I Have a Dream” Speech website (The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University in collaboration with Beacon Press’s King Legacy Series)Lauren Feeney, “Two Versions of John Lewis’ Speech,” Moyers and Company, 24 July 2013Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Meredith Roman, “The Black Panther Party and the Struggle for Human Rights,” Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men 5, 1, The Black Panther Party (Fall 2016), 7-32Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Michael J. Kramer, “The Woodstock Transnational: Rock Music & Global Countercultural Citizenship After the Vietnam War,” The Republic of Rock Book Blog, 22 October 2018Optional Brockport Faculty Talk: R-E-S-P-E-C-T and the Social Movements of the Sixties1969-2001Week 12 — Resignations and Demolitions: The Seventies — Living in a Material World: The EightiesGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 26, The Conservative Turn, 1969-1988, 808-845Voices of Freedom, Ch. 26, 306-331Tim Barker, “Other People’s Blood,” N 1, 34, Spring 2019Moira Donegan, “How to Survive a Movement: Sarah Schulman’s monumental history of ACT UP,” Bookforum, 1 June 2021Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: James Spiller, “Nostalgia for the Right Stuff: Astronauts and Public Anxiety about a Changing Nation,” in Michael Neufeld ed., Spacefarers: Images of Astronauts and Cosmonauts in the Heroic Era of Spaceflight (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Scholarly Press, 2013), 57-76, on BrightspaceWeek 13 — The End of the Cold War and the Rise of Neoliberalism: The NinetiesGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 27, A New World Order, 1989-2004, 846-886Voices of Freedom, Ch. 27, 332-3452001-2024Week 14 — Thanksgiving Optional: Lawrence B. Glickman, “The Fruits of Their Labors: How Thanksgiving became a free-enterprise holiday,” Slate, 22 November 2021Week 15 — Making America Great Again? Recent US History in Historical ContextGive Me Liberty!, Ch. 28, A Divided Nation, 887-933Voices of Freedom, Ch. 28, 348-367Adam Serwer, “The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts,” The Atlantic, 23 December 2019, on BrightspaceAssignmentsDUE BY START OF WEEK 02 (Mo 09/02)—Student Info FormDUE WEEK 03 (Mo 09/09) 10%—Very Short Assignment 01: Contextualize the Petition of Committee on Behalf of the Freedmen to Andrew JohnsonDUE WEEK 06 (Mo 09/30) 10%—Very Short Assignment 02: Industrialization in the US After the Civil War: Designing An Essay Assignment to Teach Change Over Time, Causality, Contingency, or ComplexityDUE WEEK 07 (Mo 10/07) 5%—Illumine EBook Quizzes Part 01DUE WEEK 07 (Mo 10/07) 15%—Inquizitives Part 01DUE WEEK 12 (Mo 11/11) 10%— Very Short Assignment 03: Progress or No?DUE END OF COURSE (Mo 12/14) 5%—Illumine EBook Quizzes Part 02DUE END OF COURSE (Mo 12/14) 15%—Inquizitives Part 02DUE END OF COURSE (Mo 12/14) 20%—Make Your Own Damn Lecture: Final Contextualization and Interpretation Voicethread EssayDUE END OF COURSE (Mo 12/14) 10%—Attendance, In-Class Worksheets, and Participation. Please note attendance policy below: you may miss up to four class meetings no questions asked, with or without a justified reason (this includes sports team travel, illness, or other reasons). You do not need to notify the instructor of your absences.I do not offer extra credit in this course.

EvaluationThis course uses a simple evaluation process to help you improve your understanding of both US history since the Civil War and history as a method. Note that evaluations are never a judgment of you as a person; rather, they are meant to help you assess how you are processing material in the course and how you can keep improving college-level and lifelong skills of historical knowledge and skills. Remember that history is a craft and it takes practice and iteration to improve, as with any knowledge and skill you wish to develop; but, if you keep at it, thinking historically can help you understand the complexities of the world more powerfully.

There are four evaluations given for assignments—(1) Yes!; (2) Getting Closer; (3) Needs Work; (4) Nah—plus comments, when relevant, based on the rubric below. Late assignments will lose one grade per each day they are late.

Remember to honor the Academic Honesty Policy at SUNY Brockport, including no plagiarism. In this course there is no need to use sources outside of the required ones for the class. The instructor recommends not using algorithmic software such as ChatGPT for your assignments, but rather working on your own writing skills. If you do use algorithmic software, you must cite it as you would any other secondary source that is not your own. For more information on SUNY Brockport’s Academic Honesty Policy.

Please note again: I do not offer extra credit in this course.

Overall course rubricYes! = A-level work. These show evidence of:

clear, compelling writing assignments that include:a credible, persuasive argument with some originalityargument persuasively supported by relevant, accurate and complete evidencepersuasive integration of argument and evidence in an insightful analysisexcellent organization: introduction, topic sentences, coherent paragraphs, use of evidence, contextualization, analysis, smooth transitions, conclusionprose free of spelling and grammatical errors with lack of clichéscorrect page formatting when relevant, with regular margins, 12-point font, double spacedaccurate formatting of footnotes and bibliography with required citation and documentationon-time submission of assignmentsYour essay should include (as per Joel M. Sipress, “Why Students Don’t Get Evidence and What We Can Do About It,”The History Teacher, 37, 3, May 2004, on Jstor and Brightspace):Thesis—The “thesis” is the point that you are trying to prove. It is the thing of which you are trying to persuade the audience. It is your answer to the important question. A good thesis can usually be expressed in a sentence or two. The ability to formulate a clear and concise thesis is the fundamental skill of argumentation. One cannot argue effectively for a position unless it is clear what that position is.Summary—Arguments often take the form of a response to another person’s argument. In order to respond effectively to an argument, one must first be able to effectively identify and summarize that other person’s argument, including the other person’s thesis.Organization—In order to demonstrate a thesis, one must present points in support of that thesis. The persuasiveness of the argument depends largely upon the organization with which one presents the supporting points. The key to a well-organized argument is to present the supporting points one at a time in a logical order.Evidence—The fundamental criteria by which the persuasiveness of an argument should be judged is the degree to which specific evidence is provided that demonstrates the thesis and supporting points. The ability to locate and present such evidence is thus a fundamental skill of argumentation. Your essay should generally try to engage at least one, if not more than one, of the “5 C’s” as described in Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke. “What Does It Mean to Think Historically?,” Perspectives on History, January 2007. These are: Change over timeContextCausalityContingencyComplexityfor class meetings, regular attendance and timely preparation overall, plus insightful, constructive, respectful, and regular participation in class discussionsoverall, a thorough understanding of required course materialGetting Closer = B-level work, It is good, but with minor problems in one or more areas that need improvement.

Needs work = C-level work is acceptable, but with major problems in several areas or a major problem in one area.

Nah = D-level work. It shows major problems in multiple areas, including missing or late assignments, missed class meetings, and other shortcomings.

E-level work is unacceptable. It fails to meet basic course requirements and/or standards of academic integrity/honesty.

Successful assignments demonstrate:

Argument – presence of an articulated, precise, compelling argument in response to assignment prompt; makes an evidence-based claim and expresses the significance of that claim; places argument in framework of existing interpretations and shows distinctive, nuanced perspective of argument. Your argument should engage at least one of the “how to think historically” categories: Change over time; context; causality; contingency; complexity. From Joel Sipress: Thesis—The “thesis” is the point that you are trying to prove. It is the thing of which you are trying to persuade the audience. It is your answer to the important question. A good thesis can usually be expressed in a sentence or two. The ability to formulate a clear and concise thesis is the fundamental skill of argumentation. One cannot argue effectively for a position unless it is clear what that position is.Evidence – presence of specific evidence from primary sources to support the argument. From Joel Sipress: Evidence—The fundamental criteria by which the persuasiveness of an argument should be judged is the degree to which specific evidence is provided that demonstrates the thesis and supporting points. The ability to locate and present such evidence is thus a fundamental skill of argumentation.Argumentation – presence of convincing, compelling connections between evidence and argument; effective explanation of the evidence that links specific details to larger argument and its sub-arguments with logic and precisionContextualization – presence of contextualization, which is to say an accurate portrayal of historical contexts in which evidence appeared and argument is being made. From Joel Sipress: Summary—Arguments often take the form of a response to another person’s argument. In order to respond effectively to an argument, one must first be able to effectively identify and summarize that other person’s argument, including the other person’s thesis.Citation – wields Chicago Manual of Style citation standards effectively to document use of primary and secondary sourcesOrganization and Style – presence of logical flow of reasoning and grace of prose, including:an effective introduction that hooks the reader with originality and states the argument of the assignment and its significanceclear topic sentences that provide sub-arguments and their significance in relation to the overall argumenteffective transitions between paragraphsa compelling conclusion that restates argument and adds a final pointaccurate phrasing and word choiceuse of active rather than passive voice sentence constructionsFrom Joel Sipress: Organization—In order to demonstrate a thesis, one must present points in support of that thesis. The persuasiveness of the argument depends largely upon the organization with which one presents the supporting points. The key to a well-organized argument is to present the supporting points one at a time in a logical order.Citation and style guide: Using Chicago Manual of StyleThere is a nice overview of citation at the Chicago Manual of Style websiteFor additional, helpful guidelines, visit the Drake Memorial Library’s Chicago Manual of Style pageYou can always go right to the source: the 17th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style is available for reference at the Drake Memorial Library Reserve DeskWriting consultationWriting Tutoring is available through the Academic Success Center. It will help at any stage of writing. Be sure to show your tutor the assignment prompt and syllabus guidelines to help them help you.

Research consultationThe librarians at Drake Memorial Library are an incredible resource. You can consult with them remotely or in person. To schedule a meeting, go to the front desk at Drake Library or visit the library website’s Consultation page.

Attendance policyYou will certainly do better with evaluation in the course, learn more, and get more out of the class the more you attend meetings, participate in discussions, complete readings, and finish assignments. That said, lives get complicated. Therefore, you may miss up to four class meetings, with or without a justified reason (this includes sports team travel, illness, or other reasons). You do not need to notify the instructor of your absences.

If you are ill, please stay home and take precautions if you have any covid or flu symptoms. Moreover, masks are welcome in class if you are still recovering from illness or feel sick.After six absences, subsequent absences will result in reduction of final course grade at the discretion of the instructor. Generally, more than five absences results in the loss of one grade per additional absences from final course evaluation.

Please note again: I do not offer extra credit in this course.

Disabilities and accommodationsIn accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and Brockport Faculty Senate legislation, students with documented disabilities may be entitled to specific accommodations. SUNY Brockport is committed to fostering an optimal learning environment by applying current principles and practices of equity, diversity, and inclusion. If you are a student with a disability and want to utilize academic accommodations, you must register with Student Accessibility Services (SAS) to obtain an official accommodation letter which must be submitted to faculty for accommodation implementation. If you think you have a disability, you may want to meet with SAS to learn about related resources. You can find out more about Student Accessibility Services or by contacting SAS via the email address sasoffice@brockport.edu or phone number (585) 395-5409. Students, faculty, staff, and SAS work together to create an inclusive learning environment. Feel free to contact the instructor with any questions.

Discrimination and harassment policiesSex and Gender discrimination, including sexual harassment, are prohibited in educational programs and activities, including classes. Title IX legislation and College policy require the College to provide sex and gender equity in all areas of campus life. If you or someone you know has experienced sex or gender discrimination (including gender identity or non-conformity), discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or pregnancy, sexual harassment, sexual assault, intimate partner violence, or stalking, we encourage you to seek assistance and to report the incident through these resources. Confidential assistance is available on campus at Hazen Center for Integrated Care. Another resource is RESTORE. Note that by law faculty are mandatory reporters and cannot maintain confidentiality under Title IX; they will need to share information with the Title IX & College Compliance Officer.

Statement of equity and open communicationWe recognize that each class we teach is composed of diverse populations and are aware of and attentive to inequities of experience based on social identities including but not limited to race, class, assigned gender, gender identity, sexuality, geographical background, language background, religion, disability, age, and nationality. This classroom operates on a model of equity and partnership, in which we expect and appreciate diverse perspectives and ideas and encourage spirited but respectful debate and dialogue. If anyone is experiencing exclusion, intentional or unintentional aggression, silencing, or any other form of oppression, please communicate with me and we will work with each other and with SUNY Brockport resources to address these serious problems.

Disruptive student behaviorsPlease see SUNY Brockport’s procedures for dealing with students who are disruptive in class.

Emergency alert systemIn case of emergency, the Emergency Alert System at The College at Brockport will be activated. Students are encouraged to maintain updated contact information using the link on the College’s Emergency Information website.

Learning goalsThe study of history is essential. By exploring how our world came to be, the study of history fosters the critical knowledge, breadth of perspective, intellectual growth, and communication and problem-solving skills that will help you lead purposeful lives, exercise responsible citizenship, and achieve career success. History Department learning goals include:

Articulate a historical question and thesis in response to it through analysis of empirical evidenceAdvance in logical sequence principal arguments in defense of a historical thesisProvide relevant evidence drawn from the evaluation of primary and/or secondary sources that supports the primary arguments in defense of a historical thesisEvaluate the significance of a historical thesis by relating it to a broader field of historical knowledgeExpress themselves clearly in writing that forwards a historical analysis.Use disciplinary standards (Chicago Manual of Style) of documentation and citation when referencing historical sourcesIdentify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they appear in their own and others’ workDemonstrate understanding of the methods historians use to explore social phenomena, including observation, hypothesis development, measurement and data collection, experimentation, evaluation of evidence, and employment of interpretive analysisDemonstrate knowledge of major concepts, models and issues of US history since the Civil WarDevelop proficiency in oral discourse through class participation and discussion