Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 26

February 3, 2022

Creating the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project

Sam Hinton (guitar) and Barry Olivier, 1964. Photo credit: Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Sam Hinton (guitar) and Barry Olivier, 1964. Photo credit: Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.Published at the National Council on Public History’s History@Work blog, the three-part blog post “Digital public history as folk music hootenanny” explores the development of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project.

Part 1 relates how I came into contact with this remarkable “analog” archive itself.

Part 3 looks to where the project is headed next in its attempts to make fruitful links between folk music revivalism (with all its problems and issues as well as its possibilities and potential) and digital public history futurism.

February 2, 2022

Orature

Adewale S. Adenle, Dancing in Congo Square, 2010.

Adewale S. Adenle, Dancing in Congo Square, 2010.Orature is an art of listening as well as speaking; improvisation is an art of collective memory as well as invention; repetition is an act of re-creation as well as restoration.

— Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance

Berkeley Folk Music Festival Digital Exhibit Receives Award

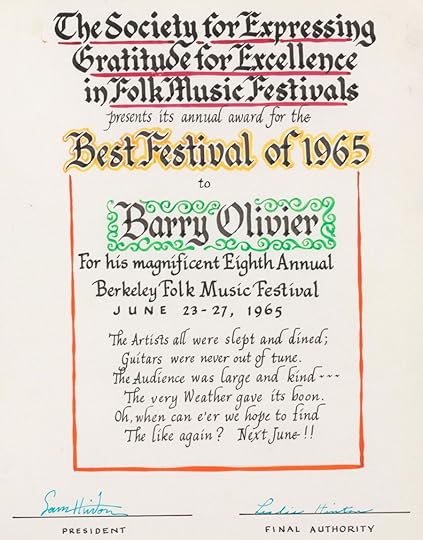

Certificate given to Berkeley Folk Music Festival Director Barry Olivier by master of ceremonies and musician Sam Hinton for the 1965 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Certificate given to Berkeley Folk Music Festival Director Barry Olivier by master of ceremonies and musician Sam Hinton for the 1965 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.The Popular Culture Association has awarded the 2022 Allen Ellis Digital Research Award in Popular Culture to The Berkeley Folk Music Festival & the Folk Revival on the US West Coast—An Introduction. Thanks to SUNY Brockport librarian Mary Jo Orzech for nominating the project. The free Popular Culture Association membership that comes with the award will be given to a SUNY Brockport student interested in attending the 2022 PCA Virtual Conference and studying popular culture more deeply. For more about the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project, visit bfmf.net.

January 31, 2022

Rovings

Thomas Hirschhorn, “Can I Trust You?”, 2020 from Art As Connection, Aargauer Kunsthaus.SoundsA Tango with Robert Farris Thompson, AfroPop WorldwideEmily Bick Presents Adventures in Sound & Music, November 2021Seaketa “Ranbu,” Tetra Hysteria ManifestoJohnny Alf, Eu e a BrisaJohnny Alf, O Autor (Ao Vivo)Cat Power, CoversJim O’Rourke NTS Radio showBlaze Foley, Sittin’ By the RoadBill Dixon, Son of SisyphusS.E. Rogie, The New Sounds of S.E. RogieLord Melody, “Booboo Man”Mighty Sparrow, “No, Doctor, No (The Situation in Trinidad)”Jon Boden, “Under the Influence,”

The Essay

, BBC3 Radio

Unclassified

with Elizabeth Acker,

BBC Radio

Manu Dibango et Son Orchestre, “Le Lion Est Mort,” Surboum African Jazz, 1962, played by Chris Albertyn on Doug Schulkind’s Give the Drummer Some, 28 January 2022WordsBen Opie, “Unsolved Mysteries: Conglomerate Records,”

Anomaly Index,

17 July 2020James Elkins, ed. The State of Art CriticismRaphael Rubinstein, Critical Mess: Art Critics on the State of Their PracticeJarrett Earnest, What It Means to Write About Art: Interviews with Art CriticsThomas Docherty, Aesthetic DemocracyJonathan P. Eburne, Outsider Theory: Intellectual Histories of Unorthodox IdeasAdam Gordon, Prophets, Publicists, and Parasites: Antebellum Print Culture and the Rise of the CriticMaureen A. Flanagan, America Reformed: Progressives and Progressivisms, 1890s-1920sErik Loomis, A History of America in Ten StrikesLisa McGirr, Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American RightElliott Sharp, “Peter K. Siegel: Quietly Changing American Music,” Please Kill Me, 6 January 2022Victoria Lindsay Levine and Dylan Robinson, eds., Music and Modernity Among First Peoples of North AmericaLuisa Passerini, Across the Atlantic: Cultural Exchanges Between Europe and the United StatesAkira Iriye, Cultural Internationalism and World OrderBrent Cebul, Lily Geismer, and Mason B. Williams, eds., Shaped by the State: Toward a New Political History of the Twentieth CenturyMelinda Cooper, “Family Capitalism and the Small Business Insurrection,” Dissent, Winter 2022Jessica Swoboda, “Speculative Thinking A conversation with Joel Rhone,” The Point, 25 January 2022Jesse McCarthy, “On Afropessimism,”

Los Angeles Review of Books

, 20 July 2020Anastasia Berg and Rachel Wiseman, “Motherhood and Taboo: Recovering The Lost Daughter,” The Point, 14 January 2022Brian D. Behnken, Gregory D. Smithers, and Simon Wendt, eds. Black Intellectual Thought in Modern America: A Historical PerspectiveJeffrey C. Alexander, Trevor Stack, and Farhad Khosrokhavar, eds., Breaching the Civil Order: Radicalism and the Civil Sphere“Walls”

Donald Judd, Paintings 1959–1961

, GagosianNo Humans Involved, Hammer Museum

Art As Connection

, Aargauer KunsthausEtel Adnan: Light’s New Measure, GuggenheimEd Clark: Without a Doubt, Hauser & Wirth

Rachel Rose: Enclosure

, Gladstone Gallery“Stages”Intellectual Histories of Global Capitalism Workshop #1, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and SocietyScreensThe Secret Agent, BBCThe Eternals

Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles

Some American Feminists

Atlantic Crossing, Season 01Billions, Season 06Shadow Lines, Season 02The Gilded Age, Season 01The Book of Boba Fett, Season 01Yellowstone, Season 01

Thomas Hirschhorn, “Can I Trust You?”, 2020 from Art As Connection, Aargauer Kunsthaus.SoundsA Tango with Robert Farris Thompson, AfroPop WorldwideEmily Bick Presents Adventures in Sound & Music, November 2021Seaketa “Ranbu,” Tetra Hysteria ManifestoJohnny Alf, Eu e a BrisaJohnny Alf, O Autor (Ao Vivo)Cat Power, CoversJim O’Rourke NTS Radio showBlaze Foley, Sittin’ By the RoadBill Dixon, Son of SisyphusS.E. Rogie, The New Sounds of S.E. RogieLord Melody, “Booboo Man”Mighty Sparrow, “No, Doctor, No (The Situation in Trinidad)”Jon Boden, “Under the Influence,”

The Essay

, BBC3 Radio

Unclassified

with Elizabeth Acker,

BBC Radio

Manu Dibango et Son Orchestre, “Le Lion Est Mort,” Surboum African Jazz, 1962, played by Chris Albertyn on Doug Schulkind’s Give the Drummer Some, 28 January 2022WordsBen Opie, “Unsolved Mysteries: Conglomerate Records,”

Anomaly Index,

17 July 2020James Elkins, ed. The State of Art CriticismRaphael Rubinstein, Critical Mess: Art Critics on the State of Their PracticeJarrett Earnest, What It Means to Write About Art: Interviews with Art CriticsThomas Docherty, Aesthetic DemocracyJonathan P. Eburne, Outsider Theory: Intellectual Histories of Unorthodox IdeasAdam Gordon, Prophets, Publicists, and Parasites: Antebellum Print Culture and the Rise of the CriticMaureen A. Flanagan, America Reformed: Progressives and Progressivisms, 1890s-1920sErik Loomis, A History of America in Ten StrikesLisa McGirr, Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American RightElliott Sharp, “Peter K. Siegel: Quietly Changing American Music,” Please Kill Me, 6 January 2022Victoria Lindsay Levine and Dylan Robinson, eds., Music and Modernity Among First Peoples of North AmericaLuisa Passerini, Across the Atlantic: Cultural Exchanges Between Europe and the United StatesAkira Iriye, Cultural Internationalism and World OrderBrent Cebul, Lily Geismer, and Mason B. Williams, eds., Shaped by the State: Toward a New Political History of the Twentieth CenturyMelinda Cooper, “Family Capitalism and the Small Business Insurrection,” Dissent, Winter 2022Jessica Swoboda, “Speculative Thinking A conversation with Joel Rhone,” The Point, 25 January 2022Jesse McCarthy, “On Afropessimism,”

Los Angeles Review of Books

, 20 July 2020Anastasia Berg and Rachel Wiseman, “Motherhood and Taboo: Recovering The Lost Daughter,” The Point, 14 January 2022Brian D. Behnken, Gregory D. Smithers, and Simon Wendt, eds. Black Intellectual Thought in Modern America: A Historical PerspectiveJeffrey C. Alexander, Trevor Stack, and Farhad Khosrokhavar, eds., Breaching the Civil Order: Radicalism and the Civil Sphere“Walls”

Donald Judd, Paintings 1959–1961

, GagosianNo Humans Involved, Hammer Museum

Art As Connection

, Aargauer KunsthausEtel Adnan: Light’s New Measure, GuggenheimEd Clark: Without a Doubt, Hauser & Wirth

Rachel Rose: Enclosure

, Gladstone Gallery“Stages”Intellectual Histories of Global Capitalism Workshop #1, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and SocietyScreensThe Secret Agent, BBCThe Eternals

Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles

Some American Feminists

Atlantic Crossing, Season 01Billions, Season 06Shadow Lines, Season 02The Gilded Age, Season 01The Book of Boba Fett, Season 01Yellowstone, Season 01

Saturation

Josef Albers, Color Study for Homage to the Square, 1963.

Josef Albers, Color Study for Homage to the Square, 1963.A work of art is permeable to the world. Let’s go further, it’s saturated by the world, by history, by modes of meaningfulness—that’s a much more productive way to think about it…

— Michael Fried, quoted in Jarrett Earnest’s What It Means to Write About Art: Interviews with Art Critics

January 30, 2022

Self Made History

Koga Harue, The Sea, 1929.

Koga Harue, The Sea, 1929.Aesthetics makes possible history as the experience of altering the self; and it is democratic precisely to the extent that such history can never be mine or mine alone, for an altered self knows no I.

— Thomas Docherty, Aesthetic Democracy

January 28, 2022

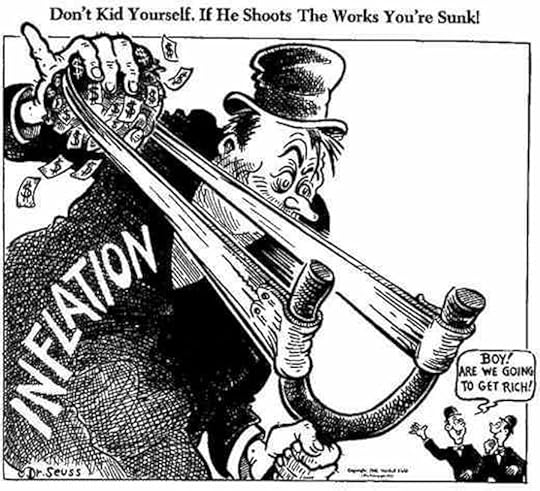

The Price Is Not Right

Robust wage growth can be good news for workers, but it also increases the risk of sustained high inflation: Companies may raise prices to try to cover rising labor costs.

Jeanna Smialek and Ben Casselman, “Inflation Continued to Run Hot and Consumer Spending Fell in December,” New York Times, 28 January 2022

What are prices really about in a capitalist economy? Is not every conversation about inflation not merely about rising prices for all, but also about who gets what within the production of wealth? Much as the careful dissociation of economic from social policy in American life tries to mask the fact, inflation is always deeply political. Prices, most would typically say, are only about the free market, with governmental monetary policy trying to keep it all in balance; yet what if prices are not only about buyers and sellers but more specifically capital and labor?

When Jeanna Smialek and Ben Casselman write in the New York Times that “companies may raise prices to try to cover rising labor costs” in response to rising wages, left unsaid is that companies might alternatively do other things, such as cover rising labor costs by making less profit. They could accumulate less capital.

Of course, no capitalist company would ever want to do that, which is why inflation in relation to wages cannot be contained within the existing workings of capitalism but almost immediately raise the specter of the limits of the existing system. Any time workers get their acts together and start to demand a fairer share of the economic pie, the result is inflationary pressure, which is to say an implicit question of who gets what from the price of goods.

So inflation in relation to higher wages is not merely a quest for justice within the existing political economy and culture; it is almost instantly also a call to change the system. Inflation always threatens to blow things up. It is the bulging bump of a fist pushing up against the membrane of accepted economic assumptions, demanding not just the redistribution of wealth, but maybe even the abandonment of the capitalist logic of limitless accumulation in its entirety. Rising prices detach goods from their grounding in productive processes. They signal crises of many sorts, including that the ideological bubble of contemporary capitalist thought might burst.

Inflation can deflate the spirit, but it also pumps up a kind of trial balloon that floats another way of potentially coexisting. Prices denote far more than what things cost today. They also tell us something about what the costs of keeping things the way they are might be for tomorrow. Speculation, so economists tell us, causes monetary inflation; so it might be too that inflation is a telltale sign of intense intellectual and political speculation.

January 27, 2022

Finding the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project

J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers with Berkeley Folk Music Festival Director Barry Olivier, 1963. Photo: Kelly Hart.

J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers with Berkeley Folk Music Festival Director Barry Olivier, 1963. Photo: Kelly Hart.Published at the National Council on Public History’s History@Work blog, the three-part blog post “Digital public history as folk music hootenanny” explores the development of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project.

Part 1 relates how I came into contact with this remarkable “analog” archive itself.

Part 2 retraces how bringing the project along required working cooperatively with librarians, archivists, students, technologists, scholars, and participants.

Part 3 looks to where the project is headed next in its attempts to make fruitful links between folk music revivalism (with all its problems and issues as well as its possibilities and potential) and digital public history futurism.

January 25, 2022

Digital History Methods Revisited

I began working seriously on digital history roughly ten years ago. Looking back, as any historian should do, here are selected essays and posts focused on research methods and a few other topics. Much more if you scroll through the pages of the Issues in Digital History blog.

Mapping, Spatial Approaches & Network AnalysisRevising Humbead’s Revised Map of the World

Mapping Humbead’s Map Interactively

Humbead’s Map Folk Music Data Viz

Timelines & “Master” NarrativesAnnotationWriting On The Past, Literally (Actually, Virtually)

Glitching & Remixing Images & SoundDistorting History (To Make It More Accurate)

A Foreign Sound To Your Ear: Digital Image Sonification for Historical Interpretation

When Mississippi John Hurt’s Head Moved

What Does A Photograph Sound Like?

Sonification & Cultural History

Podcasting & Sound AnalysisSpotify Playlists for Historical Analysis

Digitizing Folk Music History Student Showcase (including commentary on student podcast projects)

HistoriographyGoing Meta on Metadata (First posted as Digital Historiography & the Archives—Going Meta on Metadata)

TeachingDigitizing Folk Music History—Reflections 1

Digitizing Folk Music History—Reflections 2

MiscellaneousToward a Definition of Digital Public History

Five Hypotheses for Digital History

Digital History Beyond Bells and Whistles

Digital Analysis vs. Communication

Cultural Histories of the Atlantic World Reconceptualized Digitally & Interculturally—Notes on the Atlantic World Forum Project

January 1, 2022

Toward a Definition of Digital Public History

To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was’ (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.

— Walter Benjamin, Thesis VI, “On the Concept of History”

Public History: A Working DefinitionPublic history, broadly conceived, catalyzes collective attention around a topic from the past. It can do so through many means: op-eds or media appearances, monuments and material culture, interviews and oral history, music and performance, policy interventions and social justice advocacy, placards of any sort, books and articles. It can do so within institutions such as museums or parks or cultural centers. It can also do so without or beyond institutional walls. It often springs to life in the interstitial spaces between institutions and non-institutionalized social interactions, contact zones of differences in background, experience, power.

Public history can be in deep, extensive conversation with specialized scholarship, but it also tends to expand what counts as specialized scholarship. It extends who is deemed to have knowledge of the past and on what terms they possess it, wield it, and choose to (or not to) share it. Since arising in the 1970s (with antecedents prior to that), public history has been driven by the motivation to reimagine what matters as history, who gets to be a historian, and where our understandings of history get to be seen, heard, captured, displayed, processed, attended to, and addressed. In some sense all history is public history now, particularly as academic history struggles to sustain itself as a profession. Nonetheless, public history has its own rich historiography in of itself after 50 years of practice and reflection (see the National Council for Public History’s “About the Field” for more).

Public history can be deeply critical and adversarial, demanding immediate, urgent change in the moment, but just as often it involves the long game of carework and maintenance, bridge-building and sustainability, striving for transformation along more extended lines of cultural and civic labor. In either mode, it seeks to galvanize intimate encounters with structuring forces. It aims to connect the personal to the political, the individual to the collective, through multifaceted informational, interpretive, and affective experiences of the past.

It often does so through some kind of civic or even market orientation beyond the academy. It goes off campus. Or, alternatively, it seeks to bring the world beyond campus into the classroom. Either way, the goal is to manifest historical consciousness in action, to summon up the ghosts of the past in the present, to bring history to life by bringing life to history.

What is crucial to notice about exchanges between the academy and the non-academic is that they always invoke unbalanced power relations. Those on campus often seek to access the special enchantment of less formally institutionalized off-campus historical knowledge. Those off campus, meanwhile, are often curious to access the institutional resources and status that come with official scholarly attention. There is no way to remove these dynamics. Indeed, efforts to ignore them or render them invisible are typically part of the problem. What we can do is become more aware of the inequities, acknowledge them, theorize them better, and try to confront them honestly in both concrete instances and in our overall sense of what constitutes public history.

To this end, in the future it might be worth bringing public history more fully into dialogue with public sphere theory. The thinking of John Dewey, Walter Lippmann, Jürgen Habermas, Chantal Mouffe, Ernesto Laclau, the Black Public Sphere Collective, Bruno Latour, Miriam Hanson, Oscar Negt, Alexander Kluge, Michael Warner, Lauren Berlant, and others is useful for the ways in which their myriad theories of publicness complicate any simple definition of the term. Too often, public historians treat “the public” as a static entity, a fixed group. This mistakes the public for other configurations of large multitudes of diverse populations. The public should not be reduced merely to a consumer market for example, nor to a focus group. It is not an imagined mass of followers, or for that matter, on social media, “followers.” Publicity is not the same thing as publicness. Nor should we conflate citizenship with publics given the ways in which citizenship can be wielded as an exclusionary weapon by the state. Even the term community, tantalizingly warm and magical as it can feel, necessarily leaves people out. Communities necessarily require ostracization of those placed beyond the bounds of the magic circle of belonging.

Publics, by contrast, have the capacity to be more democratic than that, more expansive, more inclusive. They are weaker in a way, their bonds more ephemeral, but they are also more potent because of their looseness. A public can be a commonweal, but it can also be a difference-wheel. They can centripetally pull people into contact with each other or, just as often, spin them out centrifugally into new, expanded senses of connection across distance.

For public historians, it is worth remembering that the old term res publica quite literally means “public thing.” Public history’s attention to things—monuments, objects, maps, songs, performances, artifacts, texts—becomes one of its strengths in this sense. Things call publics into being. Old things are especially good at this. History, when handled effectively for public contemplation, fosters mobile and moving gatherings and assemblies that arise from collective attention focused on particular things. Presented truthfully and evocatively, public history’s things magnetize the past, drawing history into the present in compelling forms that organize publics around the presence of memory and meaning.

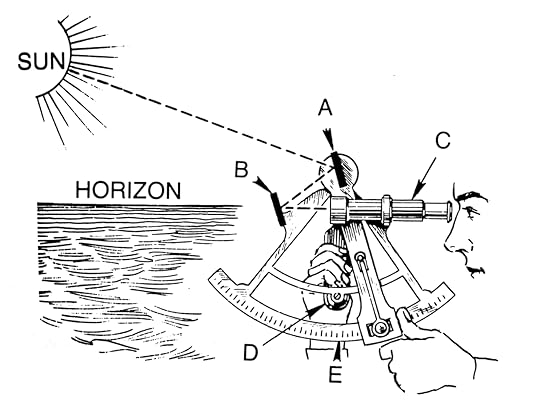

This is what public historians at their best seek to do. They wield the compass for navigating the past. They strive to pilot historical topics into contemporary life through the staging of opportunities for creative, fact-driven inquiry. These allow diverse individuals to sail together, if even just for a fleeting moment of convening, and sometimes for more sustained, continual, and lasting ensemble engagements. Public history keeps us from becoming lost at sea. Out of the past, offered up through thoughtful and expressive estimations of what direction the many have voyaged thus far, both publicness and history themselves become palpable, alive, in play, on the waves. The past makes its presence known—in transit, in the moment, with the future a horizon we glimpse with new senses by turning back for a time.

But where do digital technologies fit in, then?

Digital History: A New OrientationDigital history adds a new dimension to public history because the set of technologies we call “the digital” are disorienting and confusing. They mix up the map and the key we are accustomed to using for historical study. Things that used to seem stable and firmly in place are no longer. Digital books can now be entered into as if they were interactive exhibits. Exhibits, meanwhile, can now be read like books. An archive becomes a potential space of reenactment instead of only for storage, as in my ongoing work on the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, among many other digital history projects that consider what a repository might be when rendered digitally. Monuments, meanwhile, start to move, not only getting torn down, but also coming to life in unprecedented ways. One sees this, for instance, in the striking aesthetics of the Reclaiming the Monument project in Richmond, Virginia. Or look at the viral TikTok video of young Brits of color danced in Bristol, England atop the plinth from which a crowd had pulled down the statue of slave trader Edward Colston—a new kind of digital monument in motion, a digitally mediated commemoration in embodied form, transmitted through code.

The digital domain can be a place of storage, inquiry, interaction, publication, affirmation, protest, commentary, critique, analysis—or any combination therein. Artifacts become data, or begin their existence in born-digital form. We might consider the new possibilities this poses. The plasticity of digital data offers fresh ways of remixing, glitching, and repositioning historical artifacts for examination and contemplation. We can transform old data into new maps of the past. We can also navigate old maps by revising them into new datafied forms.

Data analysis, virtual reality, multimedia storytelling, digital animation, computational mapping, interactive gaming, and other approaches to historical artifacts open up the past for collective scrutiny. They are linked to older forms of history, to be sure. The break is not a clean one, and we should be thankful for that. Nonetheless, they beckon in radical new directions. The remediation of old artifacts as digital data (or the creation of new artifacts in the digital domain from the start) transforms the historical archive and what we can do to study it, make sense of it, and present it as history.

If public history is about catalyzing collective attention to focus on the significance of a topic from the past, then digital public history is about the power of refocusing this act of shared scrutiny. Digitization asks us to recalibrate, indeed to embrace continual recalibration as an effective mode of clarification. This is because the res publica, the “public thing” in the digital domain is at once data and also, as book artist and digital humanities theorist Johanna Drucker reminds us, “capta.” Which is to say it is constituted by things that are taken, captured, from the real world (as one would “take” a photograph) rather than things that are a given. One might, of course, say the same of many print artifacts. The analog historical record is just that: filled with analogs, things that are analogous to what actually happened. And the archive, we well know, is already ridden with distortions, gaps, problems, falsifications, untruths, and most of all silences. The digital realm merely brings this reality, already a virtuality, out into the open. It reminds us just how approximate our study of the past must sometimes be to realize the ideal of the factual, truthful, empirical.

Unfortunately, an over-hyped positivist rhetoric has dominated new fields that sing the praises of digital and computational approaches. Data science, culturomics, digital humanities have been too keen to locate themselves against qualitative, interpretative, and hermeneutic techniques. Thankfully, historians have a long history of navigating skillfully between the empirical and the theoretical. In fact (as well as in theory), the distinction between the empirical and the theoretical is a false binary for most historians. So when entering into the realm of binary code, historians, particularly public historians, are well trained to track the flux and flow between representation and the represented through a wide range of analytic tactics.

Indeed, combining methodologies of historical inquiry suits the convergences of the digital domain. As books, exhibits, repositories, monuments, performances, maps, terrains, realities, virtualities, data, capta, animations, reanimations all start to flow through the same wires and transmissions, we can draw upon what we already know to move forward. Historians grasp that the past does not serve up truth on a platter—or in an archival box of folders. The past is a mess, multifaceted and full of flavors, textures, forces barely represented at all or only appearing in shadowy traces and quieted echoes. We know to listen to the silences in the archive, to read against its grain, to look for gaps as well as connections, to know the presence of power at work in shaping how we access, perceive, and make sense of the past. Digital history merely asks us to go further into the study of relationships between representation (“capta”) and empirical reality (“data”) as they play out in bits and bytes, algorithms and programs, the electronic pulsations that now increasingly define history and how we come to know, understand, debate, and circulate it. In whatever form history scrolls past, contigent yet also determinative, we must try to unfurl it for scrutiny.

While he never used a computer, nor understood himself to be a public historian, Walter Benjamin’s evocative words still ring true. With digital public history, studying the past still involves trying to “seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.” Storms rage. The present presses in on our perceptions. And it should. We can make use of the new tools at hand to make our way forward by, paradoxically, using them to navigate our way, together, into the disorientations of the past. After all, as Benjamin himself wrote, “fanning the spark of hope in the past” in the face of histories of catastrophes and conquest, exploitation and terror, remains the duty of the historian, particularly the public historian. Today, in circuits of code, history flickers to life digitally as much, if not more, than it does anywhere else. So too, publicness itself increasingly surfaces as much on the screen and in the computerized machine as it does among bodies in the streets or words on the printed page. The task of digital public history, then, becomes an effort to seize hold of a technology as it flashes up at a moment of danger, to wield that technology as a calculator of time and space, a reorientating device of position and direction, a sextant for determining our human paths, big and small, within the larger celestial orbit.