Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 29

October 4, 2013

A Duchess Inspired by Atoms

It’s the first Friday of the month, time for another installment about the history of atom theory by award-winning physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman. Today, we meet a 17th-century English duchess so fascinated by atoms, she wrote poems about them. Lots of poems. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

Small Atomes of themselves a World may make,

Small Atomes of themselves a World may make,

As being subtle, and of every shape:

And as they dance about, fit places finde,

Such Formes as best agree, make every kinde.

For when we build a house of Bricke, and Stone,

We lay them even, every one by one:

And when we finde a gap that’s big, or small,

We seeke out Stones, to fit that place withall.

For when not fit, too big, or little be,

They fall away, and cannot stay we see.

So Atomes, as they dance, finde places fit,

They there remaine, lye close, and fast will sticke.

Those that unfit, the rest that rove about,

Do never leave, untill they thrust them out.

Thus by their severall Motions, and their Formes,

As severall work-men serve each others turnes.

And thus, by chance, may a New World create:

Or else predestined to worke my Fate.

Margaret Cavendish (public domain image via Wikipedia)

This poem, “A World made by Atomes,” is one of about 50 published in 1653 by Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673), the duchess of Newcastle. The full set of Cavendish’s Atomic Poems is available from the Emory Women Writers Resource Project. The titles of these poems range over topics such as “The weight of Atomes,” “The difference of Atomes and Motion, in youth and age” and even “All sharpe Atomes do run to the Center, and those that settle not, by reason of the straitnesse of the Place, flye out to the Circumference. Sharpe Atomes to the Center, make a Sun.” Yes, that last one is the title of a 14-line poem.

Margaret Lucas was a member of the queen’s court when the Civil War in England forced the royalty to flee to Paris. There, she met and married William Cavendish. William and his brother Charles were patrons of the sciences and interacted with many of the intellectuals of the day. Thus, Lady Margaret had the opportunity to discuss issues of science with people such as René Descartes and Pierre Gassendi, whom we discussed in the previous post and who were part of the Newcastle Circle.

The Newcastle Circle was no longer active once the English members could return to their homeland in the late 1640s. Margaret and her brother-in-law returned to England in 1651. In 1653, Margaret published two volumes of poems – Poems and Fancie and Philosophical Fancies, both of which include poems about atoms. About this latter volume, Robert Kargon states, “she expounded an atomism at once so extreme and so fanciful that she shocked the enemies of atomism and embarrassed its friends.”

Her model had four types of atoms – fire, air, earth, and water. The part is not different from the Greek philosophers. However, she also assigned shapes to each of these atoms. For example,

The Square flat Atomes, as dull Earth appeare,

The Atomes Round do make the Water cleere.

The Long streight Atomes like to Arrowes fly,

Mount next the points, and make the Aiery Skie;

The Sharpest Atomes do into Fire turne.

(First stanza of “The foure principall Figur’d Atomes make the foure Elements, as Square, Round, Long, and Sharpe”)

That is: air atoms were long, straight and hollow with a vacuum inside. Therefore they were soft. Going far beyond many of the Greeks, Margaret ascribed all types of health and sickness to atoms. In fact much illness was caused by atoms disagreeing, or fighting, with each other. For example,

When sicke the Body is, and well by fits,

Atomes are fighting, but none the better gets.

If they agree, then Health returnes againe,

And so shall live as long as Peace remaine.

(“What Atomes cause Sicknesse”)

Thus, Lady Margaret’s atoms had free will and knowledge which got them (and us) into trouble.

Detail from from frontispiece for several of her books in the 1650s and 1660s (public domain image via Wikipedia)

While she may have embarrassed other proponents of atoms, one of her contributions was to bring the ideas about the constituents of matter such as those of Descartes and Gassendi from the Continent to England. At the same time, she reopened some of the issues related to atomism and atheism. Some historians think that she was an atheist and stated so in some of her writings while others feel that she was quite pious and her statements about atheism are misunderstood.

Philosophical Fancies was published about eight months after Poems and Fancies. From the quotation above, we can see that Kargon thinks that she continued to believe in atoms although perhaps in a rather unorthodox way. Others have stated that she wrote the poems in Philosophical Fancies to begin a renunciation of her belief in atoms. For example, a statement on the Emory Women’s Writers Resource Project notes, “By 1663, she had decided that if atoms were ‘Animated matter,’ they must have ‘Free will and Liberty.’ Thus, like human nations, they would always be at war and could never cooperate to create complex animals, vegetables and minerals: ‘And as for Atoms, after I had reasoned with my Self, I concluded that it was not probable, that the Universe and all the Creatures therein could be Created and Disposed by the Dancing and Wandering and Dusty motion of Atoms.’”

Title page of The Blazing-World (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to works on natural philosophy (today called science), Margaret wrote other poems, essays, plays and The Blazing-World, a work which today is considered by many to be the first science fiction novel. In all, she published about 21 volumes.

In 1667, Margaret requested that she be allowed to visit the Royal Society during one of its meetings. The society had been formed five years earlier as a place where its (all male) members could share experiments. The duchess of Newcastle was allowed to attend the May 23 meeting where she observed experiments such as the weighing of air and the use of a microscope. However, Samuel Pepys stated that her dress and behavior made some of the Society Fellows “uneasy.” She was not invited back, and women were first allowed to become Fellows of the Royal Society in 1945.

Overall it seems that the duchess of Newcastle had both positive and negative effects on the cause of atomism. In the next post, we will look at some of the aftermath and how atoms finally started to be separated from atheism.

Previously:

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received four major awards — the American Association of Physics Teachers’ Oersted Medal (2014), the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and AAPT’s Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

September 27, 2013

Why Wallpaper? It Cost Less Than Tapestries.

My recent battle with a wallpaper border in my dining room got me to wonder: Who came up with the bright idea to decorate walls by pasting paper on them?

Certainly not my eighth-century Frankish and Saxon characters. Aristocrats decorated their walls with murals over plaster or tapestries over stone, the latter of which would help block the drafts. Peasant made do with wattle-and-daub structures.

The problem with tapestries: they were expensive. When monarchs moved from one residence to another, tapestries were important enough to be included in the carts that also carried the furniture, jewels, library, and weapons.

The credit (or blame) for wallpaper dates to 15th century France. By that time, paper making enjoyed a resurgence, and paper had supplanted parchment as material for books. The material also offered a less expensive alternative for décor.

In 1481, Louis XI commissioned Jean Bourdichon to paint 50 rolls of paper with angels, which were then mounted on panels and carted around from castle to castle. However, affixing the paper to the walls was not that far away. Around 1509, it decorated the room of the master’s lodge at Christ’s College in Cambridge, England.

Tapestries cost more, but at least they were portable and could even by given away if the new owner didn’t like them. No one had spend hours shredding, spraying, and scraping trying to get rid of them.

Sources

Ancient Inventions by Peter J. James, Nick Thorpe, I. J. Thorpe

The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, Volume 2, edited by Gordon Campbell

Rag Paper Manufacture in the United States, 1801-1900, by A.J. Valente

“Artichoke” wallpaper,designed by John henry Dearle for Morris & Co. Printed design pre-1900 (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

September 18, 2013

Controversy over a Clerical Haircut

As my manuscript for The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, a tale of the lengths a medieval Saxon mother will go to protect her children, awaits the copy editor, I am compiling a list of tweaks to make. For instance, mention that the Saxon family has to go through the city of Cologne to reach the west gate.

But there is one note where I wrote, “Never mind. Was right the right time.”

It is about tonsures. When Merovingian Queen Mother Itta converted a royal Frankish villa to a double monastery at Nivelles, she had her daughter Saint Gertrude tonsured to protect the girl’s virtue.

Nuns were tonsured? Well they did cut their hair close, the result of which was hidden under a veil. And this abbey for monks and nuns might have started out as following the Rule of Saint Columbanus or something close to it. The clerics who consulted Saint Gertrude were Irish.

So I though I would need to tweak Anglo-Saxon priest Father Osbald’s response to nine-winter-old Sunwynn’s question, “Do we have to shave our hair in that strange way?”

But by the mid-eighth century, most abbeys were shifting to Benedictine rule, and Nivelles likely was one of them at that time. So Father Osbald reply is still, “No, child. The tonsure is an honor reserved only for men of the clergy.”

As part of my research into tonsures, I encountered a controversy over exactly what hairstyle eighth century male clerics were supposed to wear. Visit English Historical Fiction Authors for my post on a tiff over tonsures.

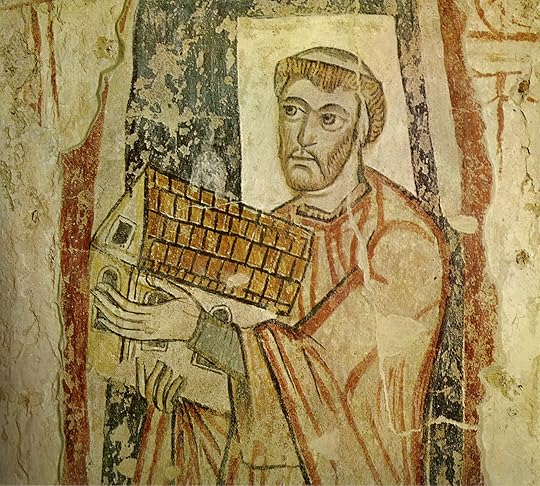

Clerics sporting the Roman tonsure (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

September 12, 2013

Charlemagne’s Court on the Move

As my husband and I prep our house for the market–decluttering, recycling, and making a gazillion trip to Goodwill–my mind wanders to what it was like for Charlemagne (748-814) and his family. Like other Frankish kings, he had to pick up and move. Constantly.

Until the later years of Charles’s reign, the royal family typically stayed at a residence for only a few months. You read that right. In the winter of 776, for example, he spent Christmas at Herstal followed by Easter at Nijmegen, then went to the assembly in Paderborn. Afterward, he spent Christmas at Douzy then Easter at Chasseneuil. Sometimes he would spend Christmas and Easter in the same place and maybe even have an assembly there, but he would often be on the move again soon.

Why all these changes in location? Well, Charles traveled with a couple of hundred of his best friends. OK, they were magnates, guards, numerous servants, livestock, and hunting dogs. The pasture and crops could sustain all those people and all those animals for only a few months.

So packing up the beds, tables, chests, clothes, weapons, the library, and the treasury was a routine thing for them. When the royal family traveled, the queen had to plan ahead. (A queen’s role was to look after the household so that her husband would be free to deal with affairs of the realm).

Along the way, the royal party might be rather expensive houseguests for a count or bishop. Yet all this travel provided a political advantage. The king’s presence reinforced his authority. A visiting king could exchange gifts with his hosts and renew oaths in an age where alliances kept the realm together.

Before arriving at their destination, servants were sent ahead to prepare the place. It was a lot of work to get a palace or even a villa ready for royalty. But at least, they didn’t have to agonize over whether a buyer would hate the décor.

Sources

Daily Life in the Age of Charlemagne, John J. Butt

Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne, Pierre Riché (translated by Jo Ann McNamara)

Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories, translated by Bernhard Walter Scholz with Barbara Rogers

This is really a fifth or sixth century image about a donation of a chapel, but it’s fun to include with a post about moving (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

September 6, 2013

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

It’s the first Friday of the month, time for another post on the history of atom theory by physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman. Here, two 17th century French philosophers take very different approaches to atoms – as well as scientific hypotheses and religious beliefs.

By Dean Zollman

During the first half of the 17th century, mechanical philosophy emerged has a dominant way of thinking about the world. This approach to philosophical thought attempts to explain the world in terms of matter and motion. Certain attributes are assigned to matter. It moves in ways that cause different pieces of matter to collide and interact with other bits of matter. The philosophers’ job is to understand the attributes and the laws of motion.

During the first half of the 17th century, mechanical philosophy emerged has a dominant way of thinking about the world. This approach to philosophical thought attempts to explain the world in terms of matter and motion. Certain attributes are assigned to matter. It moves in ways that cause different pieces of matter to collide and interact with other bits of matter. The philosophers’ job is to understand the attributes and the laws of motion.

This approach has its roots in the work of the ancient Greeks such as Democritus and Epicurus. After the rediscovery of Lucretius’s epic poem, these ideas were given further impetus by the heliocentric model of the solar system developed by Nicholaus Copernicus (1473-1543). Of course Copernicus was looking at very large objects. However, the philosophers thought, if the motion of planets and moons can be explained through mechanical means, should we not also be able to explain the actions very small matter in a similar way?

The Northumberland Circle, which was discussed last month, was one group that saw mechanical philosophy as an appropriate way to explain their observations. Two French philosophers, Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655) and René Descartes (1596–1650), were also foundational in developing ideas along these lines. However, when it came to atoms, Gassendi and Descartes had vastly different views.

1637 Portrait of Pierre Gassendi by Claude Mellan

Gassendi built on the perspectives of the early Greeks. In his view, and that of many mechanical philosophers, atoms were very small, unobservable objects which composed all matter. The fundamental atoms were indivisible but had very few properties themselves. Gassendi’s atoms had size, shape, and mass. Other properties that we observe – such as color, sound, and hardness – came about when atoms combined in different ways. In this view, atoms were in constant motion in a vacuum. Combinations and changes occurred when atoms collided with each other.

As a Catholic priest, Gassendi needed to deal with the claim that an atomistic approach did not leave room for the divine. Thus, he needed to distance his ideas from Epicurus’s view that the soul was made of atoms and decayed with the body. So, he concluded that material objects were made of atoms but that spiritual ones (souls, angels and demons) were not. Further, God created the atoms and gave them their initial motion.

Portrait of René Descartes, circa 1649, by Frans Hals

Descartes took a quite different approach. He saw matter as continuous and filling all of space. His philosophy was mechanical in the sense that he believed that matter was governed by some laws of motion that explained the objects that he saw and how those objects interact. However, he had no need for some smallest bits of matter and definitely did not believe in a vacuum. Using the ideas related to his laws of motion in which continuous matter is colliding with other continuous matter, he developed an explanation of essentially everything that he could observe.

Unfortunately, he also extended his model of the universe to some things that he could not see. In particular, he provided a mechanical explanation of Christ’s presence at the Eucharist. Some historians think that this description was a factor in Descartes’ Principia philosophiae being placed on the index of forbidden books in 1663. Thus, Descartes showed that the Eucharist was a problem for non-atomists as well as atomists and that trying to give scientific explanations to religious events was as bad an idea then as it is now.

Queen Christina of Sweden (left) and René Descartes (right). Detail from René Descartes i samtal med Sveriges drottning, Kristina. Original by Pierre Louis Dumesnil (1698-1781); 1884 copy by Nils Forsberg

An aside for people who hate mornings. In 1649, Descartes was invited to Sweden to tutor Queen Christina. Typically Descartes stayed in bed until noon, but the queen was an early morning person. She insisted that the lessons begin about 5 a.m. Some historians think that this schedule led to a rapid decline in Descartes’ health. The 5 a.m. lessons began on December 18, 1649; on February 1, 1650 Descartes became ill with pneumonia and died on February 11. Not all historians agree that early mornings killed Descartes; some even think he was assassinated.

In England, Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) developed ideas along the lines of mechanical philosophy. His model included a mechanistic description of the soul. Hobbs was also suspected of being an atheist. Thus, his embracing of the mechanical philosophy led to worries that such a philosophy would lead to atheism – a concern that we have seen before and will look at a little more the next time.

Images in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Previously:

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received three major awards—the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and American Association of Physics Teachers’ Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

August 27, 2013

Hooked on a Legend and History

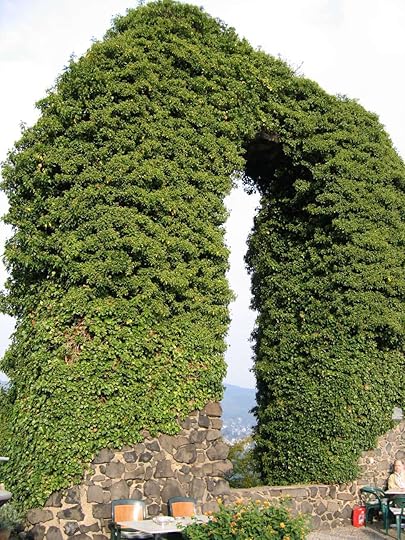

Blame it on a legend. A tale about the origin of Rolandsbogen, castle ruins on a high Rhineland hill, drew me to Roland, a prefect of the March of Brittany during Charlemagne’s reign. The history of this era has me intrigued me enough to write two books (The Cross and the Dragon and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar) and get started on a third (about Queen Fastrada).

So, when Unusual Historicals asked authors to write something on the theme of Five Fascinating Facts, how could I resist sharing a sample of what fascinates me about Charlemagne’s Francia? Visit Unusual Historicals for more.

The legend behind Rolandsbogen led me to study Frankish history (photo by Tohma via Wikimedia Commons, used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License).

August 23, 2013

Learning about Hemlock without Drinking Poison

What is an author to do if she wants to know what it’s like to be poisoned by hemlock? And she would rather not risk her life to do so.

The herb makes an appearance in both The Cross and the Dragon (2012, Fireship Press) and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar (forthcoming, Fireship Press). In Cross and Dragon, it is forced on an unconscious warrior. In Ashes, a mortally wounded warrior drinks hemlock to cut short his suffering.

I am willing to do a lot for my fiction: read academic papers and translated letters and annals, dive into archaeological reports in French and German (the first I can read, the second I use Google Translate to get the gist of just a few sentences), and be antisocial and leave a stack of messages unanswered.

What I will not do: drink poison.

Fortunately, we have Enid Bloch’s 2001 article investigating whether Plato’s account of Socrates’s peaceful death was accurate, and the modern-day novelist need not sacrifice her health.

Even better (for us), 19th century lunatic, I mean, devoted researcher John Harley experimented on himself. Yes, he deliberately consumed hemlock – twice – and literally lived to tell the tale.

I used Harley’s and Plato’s descriptions in Ashes to depict the death of Leodwulf, the brother of my heroine Leova. Here is a sample from the current draft:

“The hemlock is a mercy,” the wise woman said, meeting the twins’ gaze. “Your father’s flesh is rotting from within; even the nine sacred herbs cannot save him. If the dose is strong enough, the hemlock will spare him weeks of agony and give him a painless death. Leodwulf, you will know it’s working if you cannot feel your arms or legs.”

Leodwulf closed his eyes. His face wore a look of peace.

As the light thickened into gray, the wise woman was called to tend to another wounded man. Leova watched Leodwulf breathe. No one in the family spoke. Leova wished Derwine were here to comfort her as he had when they had lost a toddler to smallpox. She could not believe her Derwine was gone, that she would never kiss him again or hear him say she was beautiful. In the Saxon camp, she heard more murmuring and crying and shouting. Leodwulf’s hand went limp, yet Leova clung to it. While sky darkened and the moon rose, Leodwulf stared ahead. His breathing slowed.

“May the gods keep you,” he murmured, his speech slurred.

He took one more breath and stopped, his mouth open, his eyes open and unseeing.

“Leodwulf?” Leova whispered.

“Husband?” Ealdgyth asked. She pressed her fingers to Leodwulf’s neck. “May you feast well in Mother Holle’s hall, Leodwulf, son of Leof.”

If you’d like to read more of The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, check out drafts of an excerpt and the first chapter at kimrendfeld.com. If you would like to know when the novel is available, say so in a comment in the space below or e-mail me at kim [at] kimrendfeld [dot] com.

Source

“Hemlock Poisoning and the Death of Socrates: Did Plato Tell the Truth?” Journal of the International Plato Society, Enid Bloch, 2001

The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David, 1787 (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

August 16, 2013

What Did ‘Better Half’ Mean to the Franks?

Perhaps I was being unfair to Carolingian poet Theodulf who wrote the epitaph for Queen Fastrada. He says that she leaves behind King Charles (Charlemagne), whom he calls “the better part of her soul.”

I rolled my eyes, thinking he meant “superior.” What would I expect from a guy who wrote a poem warning husbands not to be manipulated by their wives? (People who are familiar with Theodulf will point out that he was a great poet of his age and he wrote a long poem praising Charles and his family. Both true, but he also did write “A Woman’s Wiles.”)

Then I came across a variation of “better half” while researching a post on Saint Lioba. In her final farewell to Frankish Queen Hildegard, Lioba kissed her and called her “most precious half of my soul.”

Perhaps the Franks attributed a different meaning to this common phrase. According to A Dictionary of Slang and Its Analogues, “better half” goes back to the Romans and originally meant more than half of one’s being, as in an intimate friend.

What Theodulf might have been getting at was that Fastrada and Charles had a close relationship, despite an age difference (probably about 20 years), a marriage made for political reasons, and a son from a previous marriage who tried to overthrow his dad.

Love was not a requirement for marriage in Carolingian Francia. Heck, husband and wife didn’t even have to like each other. So it makes Theodulf’s observation all the more poignant.

The 1882 Costumes of All Nations depicts Frankish King Charles the Bald and a woman of rank.

Sources:

A History of Charles the Great (Charlemagne)

Poetry of the Carolingian Renaissance

A Dictionary of Slang and Its Analogues

Medieval Sourcebook: Rudolph of Fulda: Life of Leoba

August 9, 2013

Research Gem: “Living in the Shadow of Death”

If you ever want to know what it was like to live with tuberculosis before antibiotics, read Sheila Rothman’s Living in the Shadow of Death. Rothman’s book spans 1810-1940, but a historical novelist can apply the stories to any era.

If you ever want to know what it was like to live with tuberculosis before antibiotics, read Sheila Rothman’s Living in the Shadow of Death. Rothman’s book spans 1810-1940, but a historical novelist can apply the stories to any era.

What was most riveting was part II, the story of Deborah Vinal Fiske, a New England woman who died at the age of 38 in 1844. Even though I was aware Deborah’s ultimate fate, I was fascinated by her story of how she tried to fulfill her duties as a wife and mother even as the disease robbed her of energy, reduced her voice to a whisper, and ultimately consumed her body.

I checked out this book from my university library when I first starting working on my novel about Queen Fastrada, Charlemagne’s fourth wife. She died young, but her illness is unknown. At first, I thought tuberculosis would be a good choice because it is unfamiliar to most of us in the West, but I decided against this disease because it is so contagious. Charles, who lived many years after her death, would not have stayed away from her. Nor would anyone else in the household.

But I could not let the information I gleaned go to waste. Thanks to this book, I learned that tuberculosis is a chronic but erratic disease. A patient could go into remission for years, and then the disease would resurface. So now it resides in my forthcoming novel, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar. The merchant who buys Leova (my heroine) interprets the return of his illnesses after years of remission as a warning from God, one that alters Leova’s situation.

The disease might make an appearance in my third book, after all. I recently read a scholarly paper speculating that Charles’s first wife, Himiltrude, was involved in eldest son Pepin’s rebellion against his father. Himiltrude lived 35-40 years and was buried at Nivelles. Now, if her cause of death was an illness…

August 2, 2013

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Lead to His Obscurity?

It’s the first Friday of the month, time for another post on the history of atom theory by physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman. Here, we’re in 17th England, and we’re introduced to Thomas Harriot, an explorer with a gift for astronomy, physics, and mathematics. Yet he is little known today.

By Dean Zollman

In 17th century England, science was making important strides in a many areas. Most people might not think of the development of the ideas of atoms has a major area for progress at that time, but progress was made. Further, ideas about atoms influenced other areas and people as well.

In 17th century England, science was making important strides in a many areas. Most people might not think of the development of the ideas of atoms has a major area for progress at that time, but progress was made. Further, ideas about atoms influenced other areas and people as well.

As I was thinking about this post, I was trying to decide whether to begin the discussion of this era with Robert Boyle or Isaac Newton. Then I discovered a little known scientist and mathematician, Thomas Harriot (also sometimes spelled Harriott, Hariot, or Heriot). Harriot (ca. 1560-1620) made significant discoveries in exploring the New World, astronomy, optics, and mathematics. He believed in the existence of atoms. As I will discuss, this belief may be the reason for our lack of knowledge about him today.

A portrait believed to be Thomas Harriot by an unknown artist.

Harriot was a friend of Sir Walter Raleigh. When two natives from the (then) New World were brought from the Americas to England, Harriot met with the Native Americans and learned their language. About 1585, he traveled to an island off the North Carolina coast. He was the only person who could communicate with local residents. (English-speaking people haven’t changed much in 430 years.) Thus, he was able to gain knowledge and insights which were published in A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia. This report proved very valuable as the English settled in (and exploited) the “new found lands.”

While they were traveling, Raleigh asked Harriot to think about the most efficient way to stack cannon balls on the deck of a ship. Harriot came up with the pyramid shape that was used until cannon balls became obsolete. Today, this stacking method is used in most pirate movies. Harriot later applied this way of packing objects to the way atoms would arrange themselves inside a material.

Upon return from America, Rayleigh introduced Harriot to the Henry Percy, the ninth earl of Northumberland. Apparently, the earl liked to have smart people to hang out with. He put Harriot, and a couple of others, on a salary. Harriot’s primary duties seemed to be to think and talk with Lord Henry.

(The earl later got into trouble because he was a suspected Catholic sympathizer, and his cousin Thomas Percy was involved in the Gunpowder Plot. He spent 17 years in the Tower of London. However, his stay was quite different from most that we think about. Lord Henry had a covered bowling alley built and a library of more than 100 books delivered to him while he was incarcerated. During his time in the Tower, the earl did not lose his wealth. So he continued to support Harriot, and Harriot visited him to discuss scientific matters.)

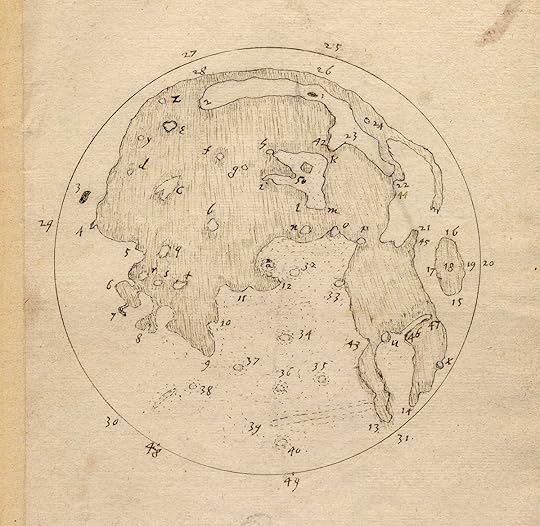

Thomas Harriot’s sketch of the moon, early 17th century.

When Harriot became interested in astronomy, he obtained the newly invented telescope and started looking at the moon. Several months before Galileo published his observations, Harriot sketched the surface of the moon. Those sketches still exist today. However, Harriot never published them, so today Galileo gets the credit.

Harriot’s contributions in mathematics are mostly in algebra. His work on using simplified symbols in algebra, and his theory of equations are considered to be way ahead of others of his time. This work was published in Latin after his death. However, Artis analyticae praxis contained many editing errors and omissions. A complete and correct translation was not published until the 21st century. As early as 1685, Rene Descartes was accused of plagiarizing Harriot in his discussion of algebra. However, today most historians discount this idea.

Harriot apparently also discovered experimentally the law which describes how light bends when it goes from one transparent medium to another. Twenty years later, Willebrord Snellius published the same idea, so the principle is now known as Snell’s Law. In between Harriot and Snell, Descartes also discovered this principle. However, it was first published in 984 by Ibn Sahl of Baghdad.

Photo by David R. Tribble

The bending of light leads us back to Harriot’s thoughts about atoms. Some of Harriot’s study of light had been motivated by an October 2, 1606, letter from Johannes Kepler. Kepler was having difficulty developing a theory for rainbows and asked Harriot for advice.

A few months later, Harriot sent a letter to Kepler describing the way light bends when it changes media. Different colors bend though different angles and create the rainbow. Then, he goes on to describe, in terms of atoms, why some light is reflected when light enters a new medium and why some of it goes into the new medium. The reflected light has bounced off atoms at the surface, while the bent (refracted) light worked its way through the new substance by moving in the empty space between the atoms. As it goes through the material, this light bounced off atoms and thus was bent. To “test” this theory, Harriot wrote to Kepler:

“I have now conducted you to the doors of nature’s mansion where her secrets are hidden. If you cannot enter because of their narrowness, then abstract and contract yourself mathematically to an atom and you will easily enter. And after you have come out, you will tell me what wonders you have seen.”

Harriot suggested that Kepler use his imagination and do what today is called a thought experiment. Kepler apparently had a limited imagination because he rejected the idea. (While Kepler was not ready for thought experiments, they have an important role in science. Three hundred years later, Albert Einstein would try to image how the world would look if he rode on a beam of light. That imaginary experiment changed the way we think about space and time.)

With so many accomplishments, Harriot published during his lifetime only the report on Virginia. Some historians claim that life was just too easy of him. He had an income for life from the earl of Northumberland. Unlike modern scientists, he never needed to compete for research grants, so he did not need to build a reputation. Others wonder if he was too sickly or too disorganized.

Another hypothesis lies in Harriot’s support of atoms. In the 17th century, the intellectual community did not separate the science of the ancient philosophers from their philosophy. As described by the Greeks, atoms were neither created nor destroyed. Because these atoms were the fundamental constituents of everything, there was no need for Creation; in fact, no need for gods.

For many in the 17th century, a belief in atoms was equated to being an atheist. And atheism was a serious crime. So, perhaps Thomas Harriot did not want to bring attention on himself and his beliefs, particularly related to atoms, by publishing his discoveries and conclusions.

For the past two (maybe three) posts, I have focused on a rather obscure event or person related to the history of atoms. Next time I will try to get back the mainstream, unless of course I get distracted again by a character as interesting as Thomas Harriot.

Postscript for historical novelists: Harriot appears in at least one novel. Harriot, Sir Walter Raleigh, and others were suspected to be members of a secret society that was sometimes called the School of Atheists. In Love’s Labor’s Lost, Shakespeare wrote “Black is the badge of hell,/The hue of dungeons and the school of night.” Much later some people speculated that the “school of night” referred to the Raleigh’s School of Atheists. The School of Night by Louis Bayard takes up this theme. It is set partially in modern day Washington DC and partially in 17th century England after Queen Elizabeth’s death. Thomas Harriot is the central character in the 17th century part of the book. (Another novel with the same title by Alan Ward is set entirely in modern times.)

Images in the public domain or used under the terms of GNU Free Documentation License, via Wikimedia Commons.

Previously:

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received three major awards—the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and American Association of Physics Teachers’ Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.