Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 26

April 4, 2014

Mme Lavoisier: Partner in Science, Partner in Life

In this installment, physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman take a side trip from the history of atom theory to introduce us to Marie Lavoisier de Rumford, who was married to two scientists in her life. One saw her as an important partner in his career; the other didn’t. And the attitudes of each man might have affected his marriage. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

This month, I will take a slight detour to describe two rather colorful people in the history of science – Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze Lavoisier de Rumford (1758-1836) and Benjamin Thompson, also known as Count Rumford (1753-1814). Both of them contributed to progress in science during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, although neither was instrumental in our understanding of the nature of matter. However, their stories make for some interesting tales.

This month, I will take a slight detour to describe two rather colorful people in the history of science – Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze Lavoisier de Rumford (1758-1836) and Benjamin Thompson, also known as Count Rumford (1753-1814). Both of them contributed to progress in science during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, although neither was instrumental in our understanding of the nature of matter. However, their stories make for some interesting tales.

Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze was the only daughter of an aristocrat, Jacques Paulze, who derived his income as a partner in Ferme Générale, which collected taxes for the French royalty. When she was 12 years old Count d’Amerval, a 50-year-old relative of a friend of her father’s boss, proposed to marry her. The count was rather poor and saw the young Marie as a way to financial security. Marie did not take well to the idea, so her father needed a way out. However, he feared that a straightforward refusal could cost him his lucrative job. The solution was to have Marie marry another partner in Ferme Générale, Antoine Lavoisier. So at the age of 13, Marie became the wife of a 28-year-old man who was to become the father of modern chemistry.

Educated in a convent, she was a bright young woman who quickly began to take an interest in her husband’s scientific endeavors. In 1777, Jean Baptiste Bucquet, one of Antoine’s collaborators, began to tutor Marie in chemistry. She also learned English during the same time period. The combination of English and chemistry became important to the progress of science.

Sharing Knowledge and Commentary

1788 Portrait of Antoine-Laurent and Marie-Anne Lavoisier by Jacques-Louis David

During this period, one of the important questions of science was what happens when an object burns. A dominant theory of the time involved a hypothesized substance, phlogiston. While phlogiston had not been isolated or measured in any way, the prevailing theory stated that it was released whenever any substance burned. This phlogiston was transferred to the surrounding air. One of the reasons that objects could not be completely burned in a closed container was that the air which was trapped inside the container became completely phlogisticated and could not absorb any more, so the fire went out.

Richard Kirwan, a British chemist, had written “Essay on Phlogiston,” an extensive description of this theory. Antoine Lavoisier was not fluent in English, so Marie translated the essay into French. However, she did much more than simply covert the words into a different language. Her translations contains notes such as, “There is in these kinds of experiences a cause of errors that seems to have escaped Mr. Kirwan.” She goes on to describe the possibility of an interaction in which water and carbonic acid escapes. She also notes about one experiment that it was conducted with a carbonate of ammonia rather than pure ammonia. In 1788, the French edition of Kirwan’s essay with notes by Mme Lavoisier was published in Paris.

The Lavoisier laboratory was one of several that measured an increase in mass when some substances burned. Thus, the idea that phlogiston was given off and took mass with it during burning was debunked. It was replaced with a concept that heat was transferred by a massless substance, called caloric, which moved from hot objects to cold ones as their temperature changed. Antoine Lavoisier was an early proponent of this theory and collected data of heat change during chemical reactions to support the theory. (Later, caloric would go the same way as phlogiston.)

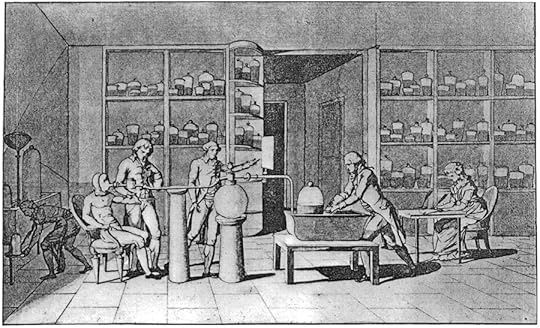

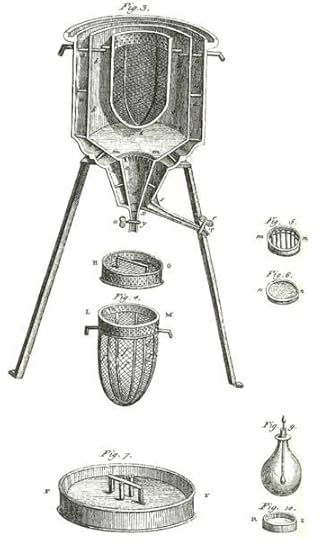

Marie Lavoisier translated other scientific papers, some of which appeared in French journals. She was also an accomplished artist. She once painted a portrait of Benjamin Franklin, the most well known America scientist of that day. The portrait has been lost, but her etchings of equipment and activities in the Lavoisier chemistry laboratory survive. Her 13 plates, produced in Antoine’s Elementary Treatise on Chemistry, show remarkable detail of the equipment in an 18th century chemistry lab. Some other drawings show experiments under way. My favorite is “Lavoisier in his laboratory: Experiments on respiration of a man at rest.” It shows the laboratory arrangement and includes a self-portrait of Mme Lavoisier to one side as she draws the experiment.

Marie Lavoisier translated other scientific papers, some of which appeared in French journals. She was also an accomplished artist. She once painted a portrait of Benjamin Franklin, the most well known America scientist of that day. The portrait has been lost, but her etchings of equipment and activities in the Lavoisier chemistry laboratory survive. Her 13 plates, produced in Antoine’s Elementary Treatise on Chemistry, show remarkable detail of the equipment in an 18th century chemistry lab. Some other drawings show experiments under way. My favorite is “Lavoisier in his laboratory: Experiments on respiration of a man at rest.” It shows the laboratory arrangement and includes a self-portrait of Mme Lavoisier to one side as she draws the experiment.

Unfortunately we do not know the full nature of the Lavoisiers’ collaboration. The values of the 18th century did not make it easy for a woman to receive proper credit for working with her husband.

After Antoine Lavoisier’s execution, Marie worked to protect and extend his reputation as a chemist. She prepared a two-volume set of his Memoirs. In a preface, she condemned six men that she felt could have come to her husband’s aid during his imprisonment. The condemnation was “scathing,” so no publisher would print the book. However, in 1803 she printed it privately and distributed copies. Two years later, the preface was removed, and the book published again.

While he was in prison, Antoine had written to Marie, “I have always enjoyed a happy life. You have made it so and continue to do so by all the signs of affection you show me.”

The Consequences of Isolation

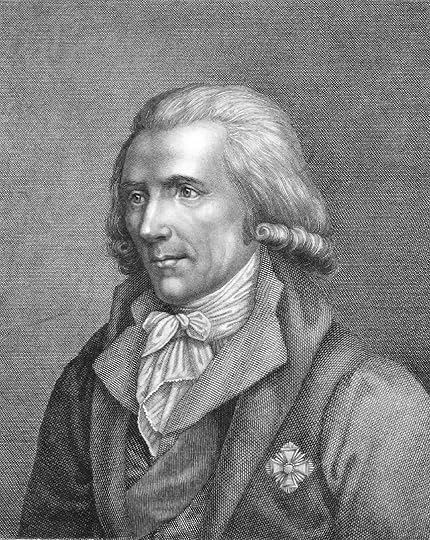

Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford

In 1801, Marie met the man who would become her second husband, Benjamin Thompson, born and raised in Massachusetts. He opposed the American Revolution, spied for the British, and eventually abandoned his family to move behind British lines. During the war, he conducted experiments on the force of gun powder. Near the end of the war, he moved to London and later to Munich. He became a count of the Holy Roman Empire in 1791 and took the name Rumford after the township in which he lived in America. By that time, he was a well known scientist.

Although some biographers have used words like scoundrel to describe him, Count Rumford’s personality did not stop him from making some important scientific and technological discoveries. He conducted many experiments and became particularly interested in the transfer of heat. In one famous observation, he noted that the amount of heat that was generated in the boring of a canon was so great that it would melt the canon if not dissipated. This observation and others led him to propose alternatives to Lavoisier’s caloric theory. (Rumford’s views on heat also would not survive into the 20th century.)

Shortly after he met Marie Lavoisier, Rumford wrote is his diary that she was “one of the cleverest women ever known and uncommonly well informed.” Their courtship was somewhat complex. Rumford was a British citizen who spent much of his time in Munich. Being British during the reign of Napoleon meant that Rumford was not welcome in France. However, after they took an extended trip in 1803 to Bavaria and Switzerland, Marie Lavoisier did convince the French government to allow Rumford to stay in France. Even then there were lots of bureaucratic barriers to their marriage, but they were finally married in 1805.

Problems with the marriage started to become apparent very quickly. Unfortunately, very little of Marie’s side of the story has survived while his side is preserved in letters to his daughter. One issue that was probably important was that Rumford mostly worked alone. This was quite different from the way Marie and Antoine Lavoisier worked as a team. Also they were quite different socially. Marie was outgoing and liked to be involved in a variety of social gathering. He, on the other hand, was somewhat isolationist both in science and social activities.

A couple of quotes exemplify the relationship. Mme Lavoisier de Rumford stated the count “would make me very happy if he would but keep quiet,” while he said in a letter to his daughter, “In character and natural propensities, Madame Rumford and myself are totally unlike.”

A story which Count Rumford wrote to his daughter on the second anniversary of the marriage conveys the depth of the problem.

“A large party had been invited [that] I neither liked nor approved of, and invited for the sole purpose of vexing me. Our house being in the centre of the garden, walled around, with iron gates, I put on my hat, walked down to the porter’s lodge and gave him orders, on his peril, not to let anyone in. Besides, I took away the keys. Madame went down, and when the company arrived she talked with them, she on one side, they on the other, of the high brick wall. After that she goes and pours boiling water on some of my beautiful flowers.”

The count frequently took refuge in his laboratory. Eventually, he set up a lab separate from their home so that he could be isolated from the woman that he had sometimes referred to as the “dragon.” So while Mme Lavoisier de Rumford did not assist the count directly in his scientific endeavors, she may have encouraged his work by giving him a reason to stay in the lab by himself.

The unhappy couple separated in 1809. Not much information survives about Marie Lavoisier after her marriage to Count Rumford. She apparently was still active in Parisian social life and took an active role in some charitable work. She died at the age of 78 in 1836.

I hope that you found this detour interesting. Next time we will return to early 19th century chemistry, which continues to be important in the development of ideas about the structure of matter.

Images via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Previously

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

Isaac Newton: 300 Years Ahead of His Time

Issac Newton and the Philosopher’s Stone

When Chemistry and Physics Split

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received four major awards — the American Association of Physics Teachers’ Oersted Medal (2014), the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and AAPT’s Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

March 31, 2014

A Little Told Side of Medieval History

When I started on my second novel, a Saxon peasant family who witnessed the destruction of the Irminsul, a historic pillar sacred to the pagans, were secondary characters. A few months later, they hijacked the plot. Their back story of lost faith and lost freedom captured my attention more than the plot I was working on at the time.

So I started over with the heroine now named Leova and her children, Deorlaf and Sunwynn. And the title that had eluded me revealed itself: The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar (forthcoming 2014, Fireship Press).

In the 21st century, we know about the destruction of pagan holy sites because of medieval Christian writers. But what about the ordinary people who witnessed these events? How did this affect their religious beliefs?

Visit Reading the Past for my post about the role historical fiction plays in portraying history through the eyes of pagans and peasants.

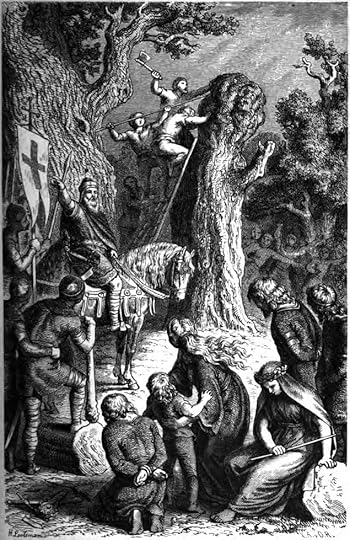

Heinrich Leutemann’s 1882 illustration of the destruction of the Irminsul (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

March 24, 2014

Saint Willibrord: ‘My God Is Stronger Than Your Devils’

When Charlemagne destroyed the Irminsul in 772 (a devastating event for my heroine in The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar), he was not the first to meddle with a site sacred to pagans. Decades earlier, Saint Boniface, the Apostle of Germany, chopped down Donar’s Oak. And before Boniface, there was Saint Willibrord, a bishop Boniface assisted in Frisia from 719 to 722.

Statue of Willibrord by Albert Termote (1889-1978) (Wikimedia Commons image used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License).

In the late seventh and early eighth centuries, Willibrord traveled as a missionary to northern Francia, Frisia, and Denmark, the last of which he gave up on except for 30 boys. Alcuin’s The Life of Saint Willibrord recounts an unplanned visit to Fositeland (Heligoland), a North Sea island between Denmark and Frisia.

Willibrord and his companions were blown to the island by a storm and stayed there to wait for better weather. They found the island’s inhabitants worshiped the god Fosite and built temples to him. The cattle who grazed at holy sites were not to be bothered, and believers were silent when they drew water from a sacred fountain.

Determined to show the pagans the falseness of their ways and unafraid of Frisian chieftain Radbod’s cruelty, Willibrord baptized three people in a ritual that required the spoken word and had some of the cattle killed for meat. As objectionable as a tolerant 21st century person might find such an act, the purpose for medieval Christians was to show that their God was stronger than pagan deities and thus spur conversions and save souls.

Alcuin says the pagans were amazed nothing bad happened to Willibrord and his company, and they reported it to Radbod.

Furious, Radbod held Willibrord and his companions for three days and cast lots three times a day to see who should die. Perhaps Radbod used lots because he feared Frankish Mayor of the Palace Pepin II, who had already defeated him in battle and seized lands, but only one of Willibrord’s party was martyred. Willibrord tried to convince Radbod that he was really worshipping devils, but as readers of last Tuesday’s post know, the Frisian ruler would not be moved. Ultimately, Radbod let Willibrord return to Francia.

Willibrord, the subject of today’s post at English Historical Fiction Authors, would go to face a difficult dilemma: whom to side with in the civil war after Pepin’s death in 714.

March 20, 2014

Women’s History Before Feminism

In too many minds, women’s history starts with the American Suffragettes in the 19th century or even the feminist movement in the 1960s. While I am truly grateful for the Suffragettes and the feminists, women have been making contributions and trying to shape events around them for eons.

It’s the reason we need Women’s History Month and why I am so glad to see the Celebrating Women series on Oh for the Hook of a Book. I am even happier to contribute to it. Today’s post features my article about Queen Mother Bertrada and her efforts to make sure her sons’ sibling rivalry didn’t escalate to civil war.

Check out future posts in the coming days. The lineup includes a great mix of authors and amazing women in history.

March 18, 2014

Frisian Chieftain Radbod: ‘I’ll See You in Hell’

In the best known legend about Frisian chieftain Radbod (d. 719), from The Life of Wulframn of Sens, he stuck his toe in the baptismal font and asked a profound question: would he see his ancestors in the afterlife? Told that his kin were in hell while he would be in heaven, Radbod refused the rite. He would rather spend eternity damned with the ancestors he loved rather than be in paradise with the Franks he hated.

We have no way of knowing whether this particular story is true, but it might reveal Radbod’s reasoning for considering conversion but staying with his pagan gods. Both decisions had more to do with politics than spirituality.

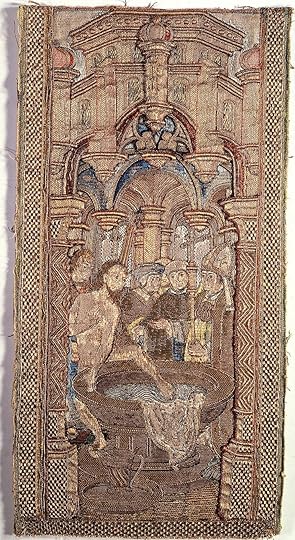

Sixteenth century embroidery depicting the legend in which the Frisian chieftain Radbod refuses baptism at the last moment (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

Around the 690s, Radbod had been fighting with Frankish Mayor of the Palace Pepin II and had even lost Utrecht and Vechten, which Pepin then colonized with Austrasian nobles. (Although Francia had a Merovingian king at that time, the mayor of the palace was the one who raised and led armies.) In addition, Pepin supported the efforts of the Northumbrian Christian missionary Willibrord, hoping to win God’s favor and a Christian Frisia that would ally itself with Francia rather than pagan Denmark or Saxony.

Unlike his predecessor, Radbod was hostile to Christianity. He might have associated a foreign religion with a foreign power.

So why would Radbod consider baptism if he hated the religion? It was a way to make peace. The bargain could have been that Radbod agree to accept baptism and stop burning churches and killing missionaries and Pepin would not try to take any more land. For an agreement to be valid, the two parties needed to swear vows, but to whose deity? To the Christians, only one is acceptable.

However, Radbod had a complication: he might have derived his power from his ties to his ancestors, especially if his family claimed to be descendants of a Germanic god. He might have thought continued war with Pepin was a better alternative than losing his right to rule.

Radbod and Pepin found another way to make peace: arranging a marriage between their children. His daughter wedded Grimoald II, a son of Pepin and his wife, Plectrude, and Radbod apparently was willing to accept his daughter’s baptism. We don’t know if that union between two people taught to hate each other was happy. Considering what happened next, I have my doubts.

The alliance fell apart when an aging and ailing Pepin died on December 16, 714. Both his sons by Plectrude were deceased, so he had named two grandsons as mayors of the palace of Neustria and Austrasia. As Plectrude tried to rule as regent, Ragenfred, a Neustrian rebel, seized power from one grandson and formed an alliance with Radbod, despite his ties with Plectrude’s late son. Together, Ragenfred and Radbod tried to take Austrasia. In the meantime, Charles, Pepin’s son by the concubine Alpais, entered the fray.

See English Historical Fiction Authors on March 24 to find out what happened and the difficult choice facing Willibrord, later a saint known as the Apostle of the Frisian.

Sources

The Carolingians: A Family who Forged Europe, Pierre Riché, translated by Michael Idomir Allen

Early Carolingian Warfare: Prelude to Empire, Bernard S. Bachrach

Heaven’s Purge: Purgatory in Late Antiquity, Isabel Moreira

March 12, 2014

Queen Bertrada: Mother of a Dynasty

Bertha Broadfoot, 1848, by Eugène Oudiné at Luxembourg Garden, Paris (copyrighted photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons).

Eugène Oudiné’s 1848 statue of Bertrada is one of my favorite artistic interpretations of this Frankish queen. Not for its historical accuracy. Other than the nickname “Bertha Broadfoot,” we have no clue for what she looked like, and the costume is not eighth century.

The reason I like it is for what she is holding in her left hand, the figure of a man on a throne. Whether he is her husband, Pepin the Short, or her son Charles the Great, it is fitting for her.

Although being able to bear a son preserved her marriage to then Mayor of the Palace Pepin, she did more than baby making. She was Pepin’s true partner when he assumed the title of king in 750 and played that role until he died in 768, dividing his kingdom between his two surviving sons. Pepin, in turn, had been a steadfast husband. His only children were born within his marriage.

As queen mother, Bertrada had a new challenge: prevent the tensions between her sons, ages 17 and 20, from turning into civil war. Read more on Unusual Historicals about how Bertrada was a female pioneer.

March 7, 2014

Redefining Elements

In this installment on the history atom theory by physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman, we meet Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, the 18th century father of modern chemistry, whose observations changed the way scientists thought about matter, elements, and how constituents of matter combine. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

In his book The Atom in the History of Human Thought, Bernard Pullman summarizes the situation that we have been considering so far.

In his book The Atom in the History of Human Thought, Bernard Pullman summarizes the situation that we have been considering so far.

“The theory of atoms was inspired in the fifth century before our era by spiritual stirrings of ancient Greece in pursuit of a novel form of philosophy. For the next twenty-three centuries, it was to remain essentially a vision of the imagination. The many intellectual debates that it stirred, however important they may have appeared at the time, were primarily games of the mind.

“Not a single piece of empirical evidence, based on either observation or experimentation, existed to prove or disprove the key hypothesis of the theory – the corpuscular structure of matter.”

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, 19th century line engraving by Louis Jean Desire Delaistre, after a design by Julien Leopold Boilly.

In the late 18th century and beyond this situation would change rapidly. Experimental studies in what we now call chemistry laid foundations upon which an atomic model of matter could be built. One important player in this experimentation was Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794), who is considered the father of modern chemistry. Many of his observations changed the way that scientists of the latter 18th and early 19th centuries thought about matter, elements, and how constituents of matter combine.

One of his most important discoveries was the Law of Conservation of Mass. Prior to his experiments, it was thought that objects would gain or lose mass as they were heated and changed from one type of material to another. For example a common experiment was to burn sulfur. When the reaction was finished, the new material was found to have a greater mass than the sulfur that the experimenter had at the beginning. Thus, it was thought, the heating process added mass to the sulfur.

Lavoisier did experiments that were more careful than those of his predecessors. Not only did he measure the mass of the sulfur compound, but he measured the mass of the air in which it was burned. He concluded that as the sulfur changed form and gained mass, the air lost the same amount of mass as that gained by the sulfur compound. (These last sentences are a little cumbersome because I am trying to avoid modern nomenclature. Today we know that the burning of sulfur in air results in the creation of sulfur dioxide – one sulfur atom and two oxygen atoms. The gain in weight of the resulting sulfur compound occurs because of the combination of sulfur with oxygen in the air.)

Ice-calorimeter, used to determine heat from chemical changes, from Antoine Lavoisier’s 1789 Elements of Chemistry.

He also investigated an experiment which had been reported by Joseph Priestley and others. When they mixed “inflammable air” (now called hydrogen) and oxygen, dew was produced. Thus, water was a combination of hydrogen and oxygen.

These and other experiments enabled Lavoisier to create a list of fundamental elements. Instead of air, water, fire, and earth, he created a list that included oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, phosphorus, zinc, sulfur, and mercury. Of course he did not get everything right; he also included light.

This list appeared in a textbook, Elements of chemistry, in a new systematic order, containing all the modern discoveries (English translation of the title). Lavoisier seemed to be on the way to showing that atoms or at least some fundamental building blocks of matter existed.

However, he was not sure. In the preface to this book he wrote, “I shall, therefore, only add upon this subject, that if, by the term elements we mean to express those simple and indivisible atoms of which matter is composed, it is extremely probable we know nothing at all about them ….” So he had discovered elements, but he was not ready to call them atoms.

In addition to being a scientist Lavoisier owed a share of a company, Ferme Generale, which collected taxes. During the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror, he and his father-in-law were arrested for his involvement in this company. They were executed by guillotine on May 8, 1794.

He was survived by his wife, Marie Anne Paulze Lavoisier, who was 13 years old when she married the 28-year-old chemist. During his life, she collaborated with him. Later she had a short, rocky marriage with the physicist Count Rumford. She did not do much to move the study of atoms forward, but she is an interesting person in the history of science. So, it is a little off task, but we will look at some of her work next time.

Images via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Previously

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

Isaac Newton: 300 Years Ahead of His Time

Issac Newton and the Philosopher’s Stone

When Chemistry and Physics Split

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received four major awards — the American Association of Physics Teachers’ Oersted Medal (2014), the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and AAPT’s Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

February 24, 2014

Who Was Saint Cuthburga?

Who was this eighth-century woman who gave up the crown in Northumbria, returned to her homeland of Wessex, and founded a double monastery that became training grounds for female missionaries sent to the Continent?

In other words, who was Saint Cuthburga?

My research into a woman whose monastery’s alumnae would influence my characters’ world yielded contradictory and confusing information. Cuthburga was married to a king but manuscripts written centuries after her death say she was a virgin. There are even different accounts of where she went in the afterlife.

See English Historical Fiction Authors for more.

19th century windows in Wimborne Minster depicting Saints Luke and Cuthburga. (Note to the sharp eyed: There are lots of ways to spell Cuthburga’s name.) From the Windows of Wimborne Minster.

February 17, 2014

Blog Hop: My Writing Process

D.M. Denton, author of A House Near Luccoli and other works, invited me to participate in this blog hop and answer four questions about my writing process. A House Near Luccoli is a beautifully written book, featuring a heroine with the soul of poet and a gifted composer with a well-earned bad boy reputation. For more about this entertaining novel, read my review on Goodreads.

My Writing Process

1) What are you working on?

The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, a tale of the lengths a medieval Saxon woman will go to protect her children. Here is a draft of the blurb:

Charlemagne’s 772 battles in Saxony have left Leova with nothing but her two children, Deorlaf and Sunwynn. Her husband died in combat. Her faith lies in the ashes of the Irminsul, the Pillar of Heaven. And the relatives obligated to defend her and her family sold them into slavery, stealing their farm.

Taken into Francia, Leova will stop at nothing to protect her son and daughter, even if it means sacrificing her honor and her safety. Her determination only grows stronger as Sunwynn blossoms into a beautiful young woman attracting the lust of a cruel master and Deorlaf becomes a headstrong man willing to brave starvation and demons to free his family.

Yet Leova’s most difficult dilemma comes in the form of a Frankish friend, Hugh. He saves Deorlaf from a fanatical Saxon Christian and is Sunwynn’s champion — and he is the warrior who slew Leova’s husband.

2) How does your work differ from others of its genre?

Not many novels are set in eighth century Francia, which comprised today’s France, Germany, Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, and Luxembourg at the start of Charlemagne’s reign. In addition, my stories show a side of history not well known among Americans.

The Cross and the Dragon presents a very different interpretation of the Roland legend. The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar gives a voice to people who otherwise have none – medieval peasants on the losing side of the Frankish-Saxon wars.

The Cross and the Dragon presents a very different interpretation of the Roland legend. The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar gives a voice to people who otherwise have none – medieval peasants on the losing side of the Frankish-Saxon wars.

Fastrada, my work in progress, tells the story of a queen who might have been made a scapegoat for the conspiracies against her husband.

3) Why do you write what you do?

I was drawn to this era by a German legend about Roland involving the origin of Rolandsbogen. Its storyline departs from the famous Song of Roland. To prevent a spoiler, I won’t elaborate, but after hearing the legend, I wanted to learn more and researched the history.

And what a fascinating history it is! Whole books have been written about it, but I will share one example to show what keeps me writing about it. In the early years of his reign, Charles seized his dead brother’s lands, a move that united Francia. To solidify his kingdom, he divorced his second wife and married a girl from an important family in his brother’s former kingdom. Charles’s widowed sister-in-law was not about to let her two little boys lose their inheritance without a fight and crossed the Alps to seek assistance from the king of Lombardy, Charles’s angry ex-father-in-law. The story gets more complicated, but eventually, Charles later found himself going to war with Lombardy to save Rome.

This is a history I feel compelled to share. On top of that, I want to give readers a different perspective than what they typically find in fiction.

4) How does your writing process work?

Although I am a creature of the 21st century and depend on my computer, Internet access, and morning coffee, I must put myself in a type of trance when I write. That means shutting off the e-mail and the social media so I can see what my characters see, feel what they feel through research and rewriting.

Even after I’ve read about historical events, what happened where, I need more. My research often delves into detail: How and where did they cross that river? What did the buildings in the city look like? How did the manor smell when fragrant herbs were strewn on the floor? What would my characters notice? When it comes to emotions, I need to see things from a medieval sensibility, but often there are remarkable similarities to modern people. After all, we’ve all loved, grieved, and experienced pure joy.

Here is one example of my writing process from The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar. First a little history: The Frankish army, led by Charlemagne, destroyed the Irminsul, a pillar sacred to the Continental Saxons. A few drafts into the novel, I realized that the destruction of the Irminsul would have been to my heroine and her contemporaries what 9/11 was to Americans. To say it in those words would have jolted the readers, so I had to think of 9/11 while describing what they saw. Here is a draft of what I came up with:

When the group reached their village at the hilltop, cries shuddered through the crowd. Longhouses were nothing more than scorched beams, and the earth on the farms was torn. The fortress’s great wooden gate looked as if a giant had ripped it asunder.

What they didn’t steal, they burned, Leova thought, stiff with fury, afraid to look to her right where the Irminsul had once stood near the river.

But she could not ignore the keening of the other Saxons. She turned, beholding the chunks of charred wood and the huge black splotch. She crossed her arms and rocked back and forth, sobbing, “All for naught, all for naught.”

Many thanks to D.M. Denton for tagging me. And now it is my pleasure to introduce three wonderful authors who will soon discuss their own writing processes.

On February 24, visit Jessica Knauss. Jessica is glad to at last call New England home. She is the author of the historical epic Seven Noble Knights, a gripping tale of family, betrayal, and revenge set in Spain, and she writes magical realism and absurd fantasy.

And on March 3, visit Tinney Sue Heath, author of A Thing Done (Fireship Press, 2012), an excellent novel in which an annoying prank snowballs into a full-blown vendetta (read my review on Goodreads). Tinney writes historical fiction set in medieval (not Renaissance!) Italy. She lives in Wisconsin in the midst of a restored prairie and plays early music on a variety of peculiar instruments, ranging from sedate to really, really loud.

Also on March 3, check out Judith Starkston, author of the forthcoming Hand of Fire, (Fireship Press, September 10, 2014), which tells the story of Briseis, the captive woman Achilles and Agamemnon fought over in the Iliad. Judith writes historical fiction and mysteries set in Troy and the Hittite Empire. In addition to her blog, her website includes book reviews and history. She also reviews for Historical Novels Review, The New York Journal of Books, and The Poisoned Pen Blog. She is a classicist (BA University of California, Santa Cruz, MA Cornell University) who taught high school English, Latin, and humanities. She and her husband have two grown children and live in Phoenix, along with their golden retriever, Socrates.

February 16, 2014

Tiddy Doll: King of Itinerant Tradesmen

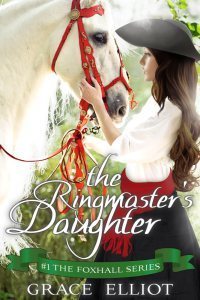

It is my pleasure to welcome author Grace Elliot to Outtakes as she makes a stop to promote her latest title, The Ringmaster’s Daughter, a romance set in a Georgian pleasure garden in 1770s London. Here, she introduces us to an unusual real-life character, a gingerbread baker named Tiddy Doll. – Kim

By Grace Elliot

My latest release is set in a Georgian pleasure garden, which is the equivalent of a modern day amusement park, and I’ve been researching 18th century entertainers and characters. The Georgian period is especially interesting because it was a time of innovation: from the theatre to the birth of the pantomime, from books to popular magazines. Advances in publishing also meant that some of the outstanding characters were captured forever in print – and one such man had the unusual name of Tiddy Doll.

My latest release is set in a Georgian pleasure garden, which is the equivalent of a modern day amusement park, and I’ve been researching 18th century entertainers and characters. The Georgian period is especially interesting because it was a time of innovation: from the theatre to the birth of the pantomime, from books to popular magazines. Advances in publishing also meant that some of the outstanding characters were captured forever in print – and one such man had the unusual name of Tiddy Doll.

Southwark Fair by William Hogarth, circa 1734

Tiddy Doll baked and sold gingerbread men and obviously had a flare for self-publicity as he became known as “the king of itinerant tradesmen.” He dressed to stand out in a crowd, wearing clothes more suited to a person of high rank than a pedlar. His usual working clothes were a laced hat topped with an ostrich plume, a laced ruffled shirt, a white gold suit of clothes, white silk stockings and a fine white apron. Indeed, an etching by Hogarth shows him center stage at Southwark market dressed in a braided hat with that extravagant ostrich plume.

If his clothes weren’t sufficient to catch the eye, he had an eloquent range of patter, often singing the words to the tune of a popular ballad.

“Mary, Mary, where do you live now Mary?

I live, when at home, in the second house in Little Ball Street,

Two steps underground, a wiscum, a riscom, and a why-not.

Walk in ladies and gentlemen, my shop is on the second floor backwards

With a knocker on the door

Here is your nice gingerbread, your spice gingerbread

It will melt in your mouth like a red-hot brick-bat

And rumble in your insides like Punch and his wheelbarrow.”

Such was his fame in popular culture of the day that his name became linked to popular sayings relating to a person who dressed above their station e.g., “You look quite the Tiddy Doll” or “You are as tawdry as Tiddy Doll.”

Perhaps part of Tiddy’s success was a cutting satirical wit. The famous print-maker James Gillray depicted him in: Tiddy-Doll the great French Gingerbread-maker, drawing out a new batch of Kings.

Perhaps part of Tiddy’s success was a cutting satirical wit. The famous print-maker James Gillray depicted him in: Tiddy-Doll the great French Gingerbread-maker, drawing out a new batch of Kings.

The print shows details such as a basket in the foreground, with the heads of men and women puppets wearing crowns and holding scepters, peeking out. The basket is labelled “True Corsican Kinglings for Home Consumption and Exportation.” Nearby a fool’s cap forms a cornucopia containing “Hot Spiced Gingerbread! All hot – come who dips in my luckey bag” – and spilling from it a coronets, crowns, scepters, and a cardinal’s hat. Tiddy Doll’s popularity went on to lend its name to a chain of popular London chop houses – the last of which closed in Mayfair in the late 1990s.

Although Tiddy doesn’t feature in The Ringmaster’s Daughter, I hope the book conveys some of the colour and vibrancy of the Georgian entertainment scene.

Grace Elliot leads a double life as a veterinarian by day and author of historical romance by night. Grace lives near London and is housekeeping staff to five cats, two teenage sons, one husband, and a bearded dragon. Grace believes that everyone needs romance in their lives as an antidote to the modern world. The Ringmaster’s Daughter is Grace’s fifth novel, and the first in a new series of Georgian romances.

Connect with Grace on her blog Fall in Love With History, her website, on Twitter @Grace_Elliot, Goodreads, Amazon, and Facebook.

About The Ringmaster’s Daughter

1770s London – The ringmaster’s daughter, Henrietta Hart, was born and raised around the stables of Foxhall Gardens. Now her father is gravely ill, and their livelihood in danger. The Harts’ only hope is to convince Foxhall’s new manager, Mr Wolfson, to let Hetty wield the ringmaster’s whip. Hetty finds herself drawn to the arrogant Wolfson but, despite their mutual attraction, he gives her an ultimatum: entertain as never before – or leave Foxhall.

1770s London – The ringmaster’s daughter, Henrietta Hart, was born and raised around the stables of Foxhall Gardens. Now her father is gravely ill, and their livelihood in danger. The Harts’ only hope is to convince Foxhall’s new manager, Mr Wolfson, to let Hetty wield the ringmaster’s whip. Hetty finds herself drawn to the arrogant Wolfson but, despite their mutual attraction, he gives her an ultimatum: entertain as never before – or leave Foxhall.

When the winsome Hetty defies society and performs in breeches, Wolfson’s stony heart is in danger. Loath as he is to admit it, Hetty has a way with horses…and men. Her audacity and determination awaken emotions long since suppressed.

But Hetty’s success in the ring threatens her future when she attracts the eye of the lascivious Lord Fordyce. The duke is determined, by fair means or foul, to possess Hetty as his mistress – and as Wolfson’s feelings for Henrietta grow, disaster looms.