Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 25

June 6, 2014

Despite Evidence of Atoms, 19th Century Skeptics Didn’t Budge

In this installment from physics professor and my dad, Dean Zollman, we find several advances in chemistry in the 19th century – as well as leaders in the field who refused to accept atomic structure despite the evidence. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

As we discussed last time, John Dalton (1766-1844) made real progress in explaining some chemical reactions in terms of atoms. Following on his work, several scientists advanced our knowledge of how elements blend to form new substances.

As we discussed last time, John Dalton (1766-1844) made real progress in explaining some chemical reactions in terms of atoms. Following on his work, several scientists advanced our knowledge of how elements blend to form new substances.

Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac (1778-1850) showed the importance of thinking in terms of volumes of gases when considering how they combined. For example, he noted that two volumes of hydrogen and one volume of oxygen mixed to make two volumes of steam. Amedio Avogadro (1776-1856) concluded that equal volumes of any gases contained equal numbers of particles. Thus, he came up with the number that many of us were required to memorize in high school chemistry. Johan Jakob Brezelius created a notation for describing how elements combined. It is basically the notation that we use today. (This notation was one place where Dalton did not succeed; he had his own notation but Brezelius’ was less cumbersome and required less knowledge of the internal structure of molecules.) In addition, several laws and rules were created based on the way particles combined in chemical reactions.

With all of these “victories,” we would expect that the opponents of atoms would give up the battle. But scientists are people first. Biases die very slowly even in the face of strong evidence to the contrary.

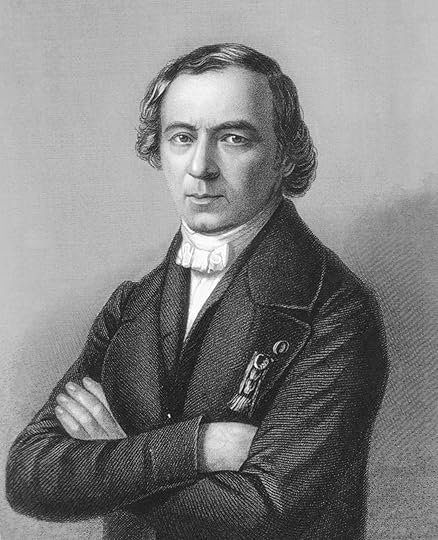

One of most outspoken opponents of the atomic structure of matter was Jean Baptiste Andre Dumas (1800-1884). An important issue was that the experiments did not clearly distinguish between atoms and molecules. Dumas and Justus Liebig (1803-1873) added to the confusion by creating two types of atoms – physical and chemical. Dumas explained this difference with an analogy.

Jean Baptiste Dumas

I find in Lewis the story of a demon who abducts a young lady and who, hoping to win her good graces, pledges to obey her first three orders: “Show me” said she, “the most sincere of all lovers.” He compiled promptly. “Very well” she continued, “but show me an even more sincere lover.” The demon was taken aback. “What would have happened had the lady been under the control of he who can show us an atom, and then divide it in two? He would experience no qualm producing the most sincere lover, followed by a more sincere still.” Mr. Griffins failed to understand that I had carefully distinguished between atoms relative to physical forces and atoms relative to chemical forces; that is to say, indivisible masses for the former, and other indivisible masses for the latter. It is thus possible to divide with one type of force that which resists the other type. In the case of chlorine and hydrogen chemistry dissociated atoms that physics could not dissociate. … That sums it up.

In this passage, we see confusion about atoms and molecules. Any volume of hydrogen gas is made of hydrogen molecules, but each molecule contains two atoms. There is nothing else but hydrogen. However, each “particle” of hydrogen can be divided into two hydrogen atoms. (Each of these atoms can be further divided, but then they are no longer hydrogen; that story will come much later.) Dumas’ solution was to create some things that could be divided by chemical processes and other things that could be divided by physical processes.

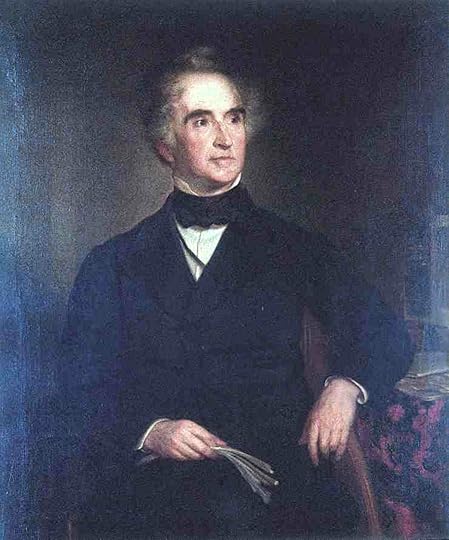

Justus Liebig, 1850

Dumas and Liebig were leaders in chemistry in the first half of the 19th century. For much of their lives they were somewhat bitter rivals. Some of their criticisms of each other seem closer to name calling than intellectual discussion. At the same time, both contributed to progress in chemistry and developed students who became the next generation of chemists in Europe. Liebig was also an applied chemist who invented chemical fertilizer, baby formula (both liquid and powered), and powdered beef bouillon. Today his laboratory in Giessen, Germany, has been restored as a museum, and it is worth a visit if you are in that area.

Justus Liebig’s laboratory in Giessen, Germany, photo by Dean Zollman

Dumas continued to be a critic of atoms as the fundamental building block of matter. He felt that atoms were theoretical constructions which could not be confirmed by experiment. Because chemistry was an experimental science, it should stick to observation. Another quotation from Dumas sums his thoughts well:

What is left of the ambitious exploration we began into the realm atoms? Nothing firm it seems.

What does remain is the conviction that chemistry strays as always when it abandons experiments and decides to proceed through the unknown. … If I were the master, I would outlaw the word “atom” from science convinced as I am that it goes far beyond experiments.

Dumas was not “the master” but he was a very influential member of the French Academy of Science. And Paris was considered a center – by some the center – of chemistry research during the first half of the 19th century. So, the concept of atoms was having a difficult time becoming established. However, things would begin to change, and we will look at some progress next time.

Portraits via Wikimedia Commons in the public domain.

Previously

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

Isaac Newton: 300 Years Ahead of His Time

Issac Newton and the Philosopher’s Stone

When Chemistry and Physics Split

Mme Lavoisier: Partner in Science, Partner in Life

With Atoms, Proportionality and Simplicity Rule

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received four major awards — the American Association of Physics Teachers’ Oersted Medal (2014), the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and AAPT’s Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

May 29, 2014

Thecla of Kitzingen: An Important Abbess in Her Day

She is little remembered now. Heck, we can’t be certain of the year she died or her feast day. But Saint Thecla of Kitzingen must have been a remarkable abbess.

With other nuns, she left the security of the double monastery at Wimbourne in her native Britain around 748 to cross the Channel and assist St. Boniface in his mission to strengthen Christianity in Francia. Travel in those days meant bad food and the danger of brigands, and women risked being raped.

The destination east of the Rhine had its own problems. In the 770s and after, Saxons to the north were not above burning churches and slaughtering indiscriminately to avenge a previous year’s defeat at the hands of the Franks. However, most of the fighting was to the north, and the Saxons did not attack Thecla’s area during her lifetime.

Boniface must have trusted Thecla a great deal because he put her charge of two abbeys, one at Ochsenfurt and the other at Kitzingen. See English Historical Fiction Authors for more about her.

A 1904 image of a Benedictine nun, public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

May 21, 2014

Independent or a Slave to Ideology?

I am happy to welcome fellow Fireship Press author M.J. Neary to Outtakes. In her excellent book, Never Be at Peace, Marina features Irish revolutionary Helena Molony. I called Helena independent in my review because she didn’t rely on a man to solve her problems. Here, Marina explains there is more to true independence. – Kim

By M.J. Neary

“No man has the right to risk the fortunes of the country to carve for himself a niche in history.”

“No man has the right to risk the fortunes of the country to carve for himself a niche in history.”

With those words Bulmer Hobson (1883-1969) issued a cryptic warning to his fellow Irish Volunteers several days before the Easter Rising of 1916. His appeal was addressed to a clique of revolutionaries who were planning an insurrection. At the time, there was a division among the Irish nationalists. Some were in favor of an armed rebellion, even though it did not stand a chance of being a military success, and others, like Hobson, considered it a frivolous waste of human life.

Helena Molony and Sean Connolly during the uprising, illustration by Alissa Mendenhall, used with permission

Helena Molony (1884-1967), Hobson’s former comrade and love interest, was in that first camp of dreamers who believed in the symbolic and redemptive power of blood sacrifice. Over the course of her long and troubled life, Molony had worn several hats. In addition to being a radical revolutionary, she was a trade unionist and an actress. To this day, she is venerated in certain IRA circles as an emblem of self-destructive martyrdom.

How often does this seemingly noble desire “to be a part of something bigger” have selfish origins? Sometimes these self-proclaimed champions of greater good are merely seeking attention, fame, and validation. The noble cause is merely a vehicle to the pedestal. Where is the line between a legitimate freedom fighter and a terrorist? Can one person shift between the two roles?

The ambiguity of intention has been the topic of my last three historical novels, all of which deal with the Irish nationalistic movement of the early 20th century. Helena Molony appears in all three, but in the last one, Never Be at Peace, she is the central figure. I find it peculiar that many of my readers define her as “independent.” And on the surface it seems like an appropriate way to define a freedom fighter, right? Not necessarily. Let’s take a closer look at the word “independent” and how it is used in the context of historical fiction.

No costume drama, be it set during the Regency, Victorian, or Edwardian era, is complete without a bodiced torso on the cover and a heroine who is described as “witty, thoroughly unconventional, and fiercely independent.” Having read countless blurbs in my life, I have developed severe allergies to the word “independent.” It’s a very dirty, misleading commercial word that publishers use.

To me, that word evokes a certain stock image: a fidgety duchess (or a shipping heiress, etc.) who “does not want to settle into the stifling conventional roles designated to them by society” and “dreams of a life outside _____ (the palace, the shipping yard)” and “explores her burgeoning sensuality in the arms of the _____ (starving artist, ruddy-faced gardener, French tutor).” Once you read the blurb, you don’t need to read the novel. I understand, there is a robust audience for such literature, and publishers have to keep the lights on, so they keep pasting these generic blurbs on the covers, even if the content is serious. Simply put, in every novel there needs to be a chain to be broken.

A protegee of Maud Gonne, Helena Molony dances with David Parkhill, illustration by Alissa Mendenhall, used with permission

One must remember, that in order to declare independence, you need to have a starting point, something to break away from, something to rebel against, something to lose. When we meet Helena for the first time, she is an orphaned teenager roaming the suburbs of Dublin, a truant without direction or any strong family attachments except for her morose brother, Frank. She just happens to meet the legendary Maud Gonne, who informally adopts her and turns her into a fervent nationalist to the point of obsession.

A child who is deprived of love and discipline is a prime candidate for becoming a fanatic in the hands of the right mentor, and fanatics by definition are not psychologically independent. They are slaves to their idea. So while Helena is fighting for Ireland’s independence, she herself is not independent. Rather, she is a weapon in the hands of another being.

Interestingly enough, Maud Gonne herself abhorred violence. Perhaps, she was a little terrified of her pupil’s enthusiasm for physical combat. By 1916, Maud was not the dominant authority figure for Helena. By that time Helena, already in her early 30s, was under the spell of James Connolly, a passionate champion for the working class, whose dream was to have a republic of free workers. It was his ideology that propelled Helena to participate in the Easter Rising. She basically moved from one idol to another.

When the Ireland she had envisioned and fought for did not materialize, Helena turned to drink. It was the devotion of another woman, Dr. Evelyn O’Brien, a much younger psychiatrist, that had saved her from stepping over the edge.

Patriotically-minded historians tended to brush Helena’s alcoholism, depression, and bisexuality under the rug. Such vices did not seem to fit with the image of the spunky and heroic tomboy in a country where morality was still dominated by the Catholic Church. Many facts did not emerge until recent decades. Now, in the 21st century, we have the freedom and the privilege to examine various historical figures as human beings with all their psychological intricacies, not mere emblems.

Born, nurtured, and warped in the radioactive swamps of Eastern Europe, M.J. Neary is a living proof that even an ugly girl can win a beauty pageant and seduce a handsome Irishman if she does her makeup right. Her literary career revolves around various disasters in Anglo-Irish history such as the Famine, the Land Wars, and the Easter Rising of 1916. Her mission is to bust stubborn ethnic myths, tell the untold stories and illuminate obscure figures through her irreverent iconoclastic style. If you are interested in Irish history and have already read everything by Morgan Llewellyn, try something different and pick up one of Neary’s novels: Brendan Malone: the Last Fenian, Martyrs & Traitors: a Tale of 1916 (both 2011, All Things That Matter Press) and Never Be at Peace: a Novel of Irish Rebels (Fireship Press, 2013).

Born, nurtured, and warped in the radioactive swamps of Eastern Europe, M.J. Neary is a living proof that even an ugly girl can win a beauty pageant and seduce a handsome Irishman if she does her makeup right. Her literary career revolves around various disasters in Anglo-Irish history such as the Famine, the Land Wars, and the Easter Rising of 1916. Her mission is to bust stubborn ethnic myths, tell the untold stories and illuminate obscure figures through her irreverent iconoclastic style. If you are interested in Irish history and have already read everything by Morgan Llewellyn, try something different and pick up one of Neary’s novels: Brendan Malone: the Last Fenian, Martyrs & Traitors: a Tale of 1916 (both 2011, All Things That Matter Press) and Never Be at Peace: a Novel of Irish Rebels (Fireship Press, 2013).

May 15, 2014

Radishes: A Sign of Spring for a Medieval Family

Wikimedia Commons photo provided by Le Grand Cricri, used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

When Leova, my heroine in The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, still had a home and her freedom in Saxony, she and her family cultivated radishes around this time of year.

Radishes appear on a list of plants Charlemagne wants in his gardens in Francia, but all classes grew them. It is possible Saxons would have raised them on their plots as well.

These veggies might have been among the first springtime vegetables on early medieval tables. Radishes can be sown as soon as the soil is workable, and they reach harvest size in as little as 21 days.

Today, most of us eat the roots raw as part of a veggie tray or salad, but they are versatile. They are delicious when added to stews, and their flavor becomes milder as they cook. Their tops also can be cooked and eaten. Although I have yet to try radish-top soup, I have no doubt that medieval peasants, always fearful of hunger, would add them to the pot.

The sight of the rounded root poking through the soil would have been welcome indeed.

Sources

Daily Life in the Age of Charlemagne by John J. Butt

Guide to Cultivated Plants by A.T.G. Elzebroek

The Victory Garden Cookbook by Marian Morash

May 7, 2014

Why Charlemagne’s Most Famous Palace Is a Villa in My Novels

Photo by Maxgreene, via Wikimedia Commons, used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation license

Even today, more than 1,200 years after its construction, Charlemagne’s octagonal chapel at Aachen Cathedral is awe-inspiring, as the entire palace complex must have been.

However, Aachen was the site of a mere royal villa in the 770s, when The Cross and the Dragon (2012, Fireship Press) and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar (August 28, 2014, Fireship Press) take place. The year 788 is the first time the Royal Frankish Annals call the royal residence a palace, and construction on the chapel didn’t start until 792.

So what is a novelist to do? How close to stick to the known facts is a matter of never-ending debate among writers of historical fiction, and the subject led to lively discussion during a recent meeting of the Historical Novel Society Great Lakes Chapter.

My own opinion is to be true to the culture, historic personages, and the times as best as you can – my medieval characters do not start their mornings with coffee, for example – but feel free to take minor liberties for the sake of the story. It is fiction after all. And this comes from someone who consulted several sources to find out whether eighth century bishops wore miters (they didn’t).

One liberty of mine is to have the Irminsul, a pillar sacred to the pagan Continental Saxons, near the fortress of Eresburg and its village. No one really knows where the Irminsul was, what it was made of, or even if there was only one, so placing it near Leova, the heroine of The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, makes sense for the story.

In the case of Aachen, I kept it a villa, although Alda, my heroine in The Cross and the Dragon, admires it and the spring-fed baths that were already there at the time. In The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, Leova is too worried about how to keep her family intact to pay much attention to her surroundings. I wanted to be accurate to the history and not jar the readers familiar with the events, but my other reason is that to use the distinctive octagonal chapel, as beautiful as it is with imported marble and a mosaic ceiling, would not have benefitted either of these stories.

Besides, the palace’s construction plays a small part in my third novel, tentatively titled Fastrada, which takes place from 783-792. Visit Unusual Historicals to find out more about how Charlemagne’s palace at Aachen was a great building of the era.

May 2, 2014

With Atoms, Proportionality and Simplicity Rule

In this installment of the history of atom theory, physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman introduces us to John Dalton, who gave us the rule of definite proportions and simplicity to explain matter.

By Dean Zollman

In the very early 19th century, Newton’s idea of forces acting among the small particles of matter and Lavoisier’s discovery of different substances combining to create a new compound would come together to form a more coherent idea about the atomic nature of chemical reactions.

An important player in this development was John Dalton (1766-1844). Dalton’s first interest was not in chemistry but in the physical properties of gasses. This interest came about because of a strong interest in meteorology and the atmosphere. He wanted to understand why the gasses in the atmosphere were mixed evenly. They could, instead, be arranged so that the oxygen, nitrogen, water vapor, and carbon dioxide were each in separate layers. (I am using modern names for the gasses rather than the ones Dalton would have used.)

1895 frontispiece of John Dalton and the Rise of Modern Chemistry

Dalton came up with a rather simple idea based on Newton’s forces between particles. He concluded that each particle of a substance repelled other particles of the same substance but did not interact with the other substances in the air. Thus, oxygen particles would repel other oxygen particles but would not affect or be affected by the nitrogen, water, or carbon dioxide particles.

This idea became rather cumbersome to explain, so Dalton later modified it. He stated that each particle of an element was surrounded by heat. The heat that surrounded oxygen would interact only with the heat of another oxygen particle, nitrogen with nitrogen, and so forth. So that caused repulsion among like atoms. All of this was based on each element having different sized atoms. This investigation led Dalton to conclude that the total pressure of a gas was the sum of the pressures of the individual gasses in the mixture.

This rather strange theory (at least strange by today’s standards) led to some careful investigation of gasses. In particular, Dalton measured the weights of elements when they combined to create new substances. For example, hydrogen and oxygen combined to make water. Dalton learned that the ratio of the weight of the hydrogen to the weight of oxygen was always the same and always a simple ratio. By weight, he discovered, water was seven parts oxygen to one part hydrogen. Further, if more than one compound was made of the same two elements, each of the compounds would be a simple ratio of weights. This fact was noticeable in the two ways that nitrogen and oxygen combined. This conclusion was the rule of definite proportions.

Based on these observations, Dalton developed an atomic theory of chemistry. This theory was published in 1808 in the book A New System of Chemical Philosophy. In addition to the ideas already discussed here, the New System included:

“… all bodies of sensible magnitude … are constituted of a vast number of extremely small particles, or atoms, of matter bound together by forces of attraction.”

“… the ultimate particles of all homogenous bodies are perfectly alike in weight, figure, &c. …”

In addition, Dalton needed to explain how atoms came together to form other substances (today we call them molecules). He enunciated a rule of simplicity. If a material is made of two kinds of atoms, they will combine in the simplest way possible. For example, if A and B combine to make C, C consists of one atom of A and one atom of B. If A and B also combine to form D, then D is two As and one B. E would be one A and two Bs, and so forth.

This rule of simplicity led to an error about the composition of water. By Dalton’s rule, water would be one atom each of hydrogen and oxygen instead of two hydrogens and one oxygen. Thus, he got the ratio of the weight of oxygen to the weight of hydrogen wrong.

How and when Dalton arrived at this theory has kept historians of science busy for almost 200 years. In a recent paper, Alan J. Rocke provides about five different scenarios that led Dalton to his conclusions. And all of them are supported by writings or reports of Dalton’s own words.

While there are some flaws in Dalton’s ideas, they did form the foundation for an atomic theory of chemistry. Thus, it was very strong support for the existence of atoms. However, it was not widely accepted in its totality by many chemists of the day. Some liked the rule of simplicity but not other parts; others embraced the proportionality idea but rejected simplicity, and so forth.

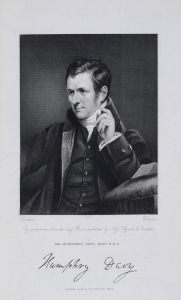

Portrait of Sir Humphrey Davy, from Sketches of the Royal Society and Royal Society Club, 1849 (provided to Wikimedia Commons by Chemical Heritage Foundation)

A well-known chemist of the day was Humphrey Davy (1778-1829). He and Dalton had frequent conversations, and Dalton had said of Humphrey that he was “a very agreeable and intelligent young man … the principle failing of his character as a philosopher is that he does not smoke.” Dalton had even used some of Davy’s observations about combinations of nitrogen and oxygen in supporting his theory.

However, in 1811 Davy stated, “I shall enter no further at present into an examination of the opinions, results and conclusions of my learned friend; I am however obliged to dissent from most of them and to protest against the interpretation that he has pleased to make of my experiments … it is not, I conceive, on any speculations upon the ultimate particles of matter that the true theory of definite proportions must ultimately rest.” Thus, Davy acknowledged that the rule of definite proportions was correct, but insisted that atoms were not the way to explain it.

So, Davy was wrong about the value of atoms; Dalton missed the boat about the value of smoking.

Many more advances occurred during the first half of the 19th century. We will continue that story next time.

Images via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Previously

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

Isaac Newton: 300 Years Ahead of His Time

Issac Newton and the Philosopher’s Stone

When Chemistry and Physics Split

Mme Lavoisier: Partner in Science, Partner in Life

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received four major awards — the American Association of Physics Teachers’ Oersted Medal (2014), the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and AAPT’s Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

April 28, 2014

Meet My Main Character: Leova, a Medieval Mom

In the latest game of tag for historical fiction authors on the blogosphere, we introduce the main character of our work in progress or soon to be published novel. Of course, I just had to introduce the heroine of The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar. My thanks to Tinney Heath, author of A Thing Done, winner of a much-deserved Sharp Writ Book Award, for tagging me.

1) What is the name of your character? Is he/she fictional or a historic person?

My main character is Leova, a pagan Continental Saxon peasant and mother of two, Deorlaf, age 12, and Sunwynn, age 9. They are products of my imagination, but the story is set against historic events.

2) When and where is the story set?

It’s set in the 770s, the earlier years of Charlemagne’s reign, when he was merely Charles, king of the Franks. The story starts in Eresburg, Saxony, (today’s Obermarsberg, Germany) and moves to several locations in Francia, including Nevers and Le Mans in today’s France. In the course of the story, Leova and her son go to Paderborn, only a three-day journey by foot to Eresburg, but then return to Francia. You’ll need to read the book to find out why.

3) What should we know about him/her?

Leova is an ordinary woman but not a typical heroine. She is a peasant, not royalty or even an aristocrat. At 28, she looks good for her age but is not a blooming maiden. Disease and the possibility of bad harvests make conditions for medieval peasants tough by our standards, yet at the beginning of the novel, Leova considers her life good, with a loving, faithful husband, two healthy children, a small farm, and a freedom she takes for granted.

4) What is the main conflict? What messes up his/her life?

War and betrayal. In 772, Charles’s Franks invade Saxony, conquer Eresburg, and destroy the Irminsul, a pillar sacred to the Saxons, all historic events. With the defeat of the Saxons, Leova loses her husband, her faith, and her home. When the relatives obliged to protect her instead sell her and her children into slavery, she even loses her freedom. All she has left are her children.

5) What is the personal goal of the character?

5) What is the personal goal of the character?

Leova will protect her children at any cost, even her own honor and safety, and she wants justice against the relatives who betrayed her.

6) Is there a working title for this novel, and can we read more about it?

It’s The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, and oh yes, can you read more. Visit kimrendfeld.com for an excerpt and the first chapter.

7) When can we expect the book to be published?

It will be published August 28, 2014, by Fireship Press. If you’d like to receive a personal note from me when it’s available in electronic and print formats, e-mail me at kim [at] kimrendfeld [dot] com.

Thanks for visiting. I have tagged five authors to follow me; they will post about their main characters about a week from now:

D.M. Denton, author of A House Near Luccoli

Elizabeth Caulfield Felt, author of Syncopation: A Memoir of Adele Hugo

Susan Keogh, author of the Jack Mallory Chronicles

Jessica Knauss, author of Seven Noble Knights and the Providence Trilogy

Susan Spann, author of the Shinobi Mysteries

April 22, 2014

How ‘Beowulf’ Influenced My Novel a Millenium Later

When I decided that the protagonists of my second novel would be a family of Continental Saxons, I turned to Beowulf as a source, even though I had no intention of including any mention of the poem, its characters, or its plot.

Why? I needed something that showed Saxon culture, and there is little written source material from that time. The Church had done everything it could to obliterate the pagan religion in Saxony, and the Continental Saxons did not have a written language as we know it.

But we have Beowulf, created sometime between the seventh and 10th centuries by an anonymous poet of a similar ethnicity. And what a gift it is to a historical novelist. Because of the poem, I understood my characters’ deep desire to avenge the wrong done to them was not only personal but cultural. I understood that even though they agreed to be baptized, the influence of pagan beliefs would linger.

But Beowulf’s creator might have drawn on more than his own culture. See my post at English Historical Fiction Authors for my speculation about the epic’s origin.

From Jean Lang’s A Book of Myths, 1915

April 14, 2014

Widukind: Hero or Villain?

Whether Widukind, leader of eighth century Westphalian Saxons in today’s Germany, was a freedom fighter depends on whose side you’re on.

To a people conquered by foreigners and shaken down for tithes following a new religion they did not understand, Widukind must have been a hero. To the Franks, he was a villain who always got away, only to come back and rouse the Saxons to again forsake their baptismal vows and loyalty oaths, burn churches, and slaughter indiscriminately.

Who’s right? For a novelist, it depends on which character is telling the story. My Franks in The Cross and the Dragon and my work-in-progress want him dead. My Saxons in The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar cheer when he escapes.

See today’s post on Unusual Historicals for more about Widukind and the complexities of the history, especially when seen through medieval eyes.

Detail of statue in Herford, Germany. (Image via Wikimedia Commons used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.)

April 8, 2014

Coming August 28, 2014: The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar

With a beautiful cover and the final edits, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar is on the path to its release on August 28, 2014! And yes, fellow grammar purists, it is worth that exclamation point.

Here is a preview of the blurb:

Can love triumph over war?

772 AD: Charlemagne’s battles in Saxony have left Leova with nothing but her two children, Deorlaf and Sunwynn. Her beloved husband died in combat. Her faith lies shattered in the ashes of the Irminsul, the Pillar of Heaven. The relatives obligated to defend her and her family instead sell them into slavery.

In Francia, Leova is resolved to protect her son and daughter, even if it means sacrificing her own honor. Her determination only grows stronger as Sunwynn blossoms into a beautiful young woman attracting the lust of a cruel master and Deorlaf becomes a headstrong man willing to brave starvation and demons to free his family. Yet Leova’s most difficult dilemma comes in the form of a Frankish friend, Hugh. He saves Deorlaf from a fanatical Saxon and is Sunwynn’s champion – but he is the warrior who slew Leova’s husband.

Set against a backdrop of historic events, including the destruction of the Irminsul, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar explores faith, friendship, and justice. This companion to Kim Rendfeld’s acclaimed The Cross and the Dragon tells the story of an ordinary family in extraordinary circumstances.

Want to read more? Check out an excerpt and the first chapter at kimrendfeld.com.