Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 23

September 17, 2014

Why You Should Listen to Your Characters

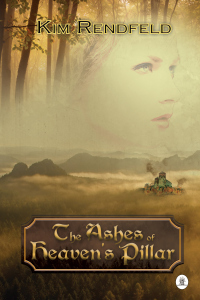

When I first started writing The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, I thought Leova and her husband, Derwine, would have a common medieval marriage: the wife feels lucky her husband doesn’t beat her up, and the husband feels lucky because he is certain he is the father of his wife’s children. My characters, however, decided differently: they deeply love each other. Visit Samantha Holt’s blog to learn why my characters were right.

September 15, 2014

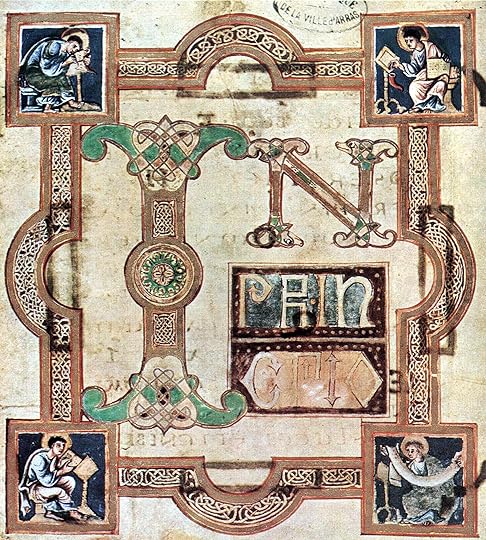

The Material for Early Medieval Reading Material

It doesn’t seem like whether a book is parchment or paper should have a major effect on society. Muslim societies favored paper, while Christians used parchment. But when you look into the process and the expense, that choice has far-reaching consequences.

Today, I’m visiting novelist and my good friend Jessica Knauss to explain why. Read the post I’ve titled “Do You Want Your Books in Paper or Parchment?“

From a 9th century gospel book (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

September 8, 2014

A Literal Trial by Fire

If you watched an early medieval trial, you would recognize the swearing of oaths on a sacred object and the questioning of witnesses, but if the judge believed in trial by ordeal with hot irons or boiling water, you might find the rest of the process problematic, to say the least.

Today, author, attorney, and my friend Susan Spann hosts my post about early medieval trials. Please visit Spann of Time for more.

Ordeal of boiling water, illustration from a 14th century manuscript, (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

September 5, 2014

The Puzzle of Dark Lines amid Rainbow Colors

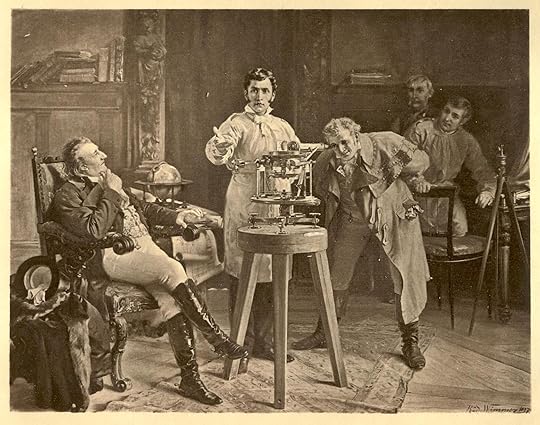

Joseph von Fraunhofer demonstrating his method of observing spectra. (Richard Wimmer, “Essays in Astronomy,” 1900, public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

In this installment on the history of atom theory, physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman discusses a mystery scientists encountered when they studied light and used prisms to create spectra: what was causing those dark lines? – Kim

By Dean Zollman

In recent posts I have been discussing the progress in understanding the relations among the elements. The evidence provided by the categories of the elements of properties and by the periodic table offered a lot of evidence that atoms existed. However, for many 19th century scientists, none of these discoveries was the “smoking gun” that conclusively proved atoms existed. By the early 20th century most of these discoveries would be explained in terms of atoms, but for many 1870s scientists, they were just interesting and useful results.

In recent posts I have been discussing the progress in understanding the relations among the elements. The evidence provided by the categories of the elements of properties and by the periodic table offered a lot of evidence that atoms existed. However, for many 19th century scientists, none of these discoveries was the “smoking gun” that conclusively proved atoms existed. By the early 20th century most of these discoveries would be explained in terms of atoms, but for many 1870s scientists, they were just interesting and useful results.

As with most fundamental scientific discoveries, the road to atoms had multiple lines of reasoning and discoveries. In this and the next posts, I will discuss another thread that started at the beginning of the 19th century and was not thoroughly explained until the first part of the 20th century. So we will back up in time to the early 19th century and follow another thread – light emitted by different substances.

Light emitted by matter is a rather common phenomenon. It is most evident in daily life as light from the sun, from burning objects, or coming from many different kinds of lamps. The ancients learned that the color of the flame varied with the type of material that was burning and that the color changed with the temperature. (The latter observation has been very important to potters for thousands of years.)

Until Isaac Newton, no one had systematically studied the light from objects. When Newton passed sunlight through a prism, he saw the light was separated into the colors of rainbow. He called this display of colors a spectrum. And the name has stuck ever since. Newton explained how a prism could form a spectrum in his Optics, but he did not investigate the spectrum itself further. (Newton’s explanation was not correct, but that’s a different story from the one that I want to tell.)

Today, we can see spectra, for example, in rainbows and in the light reflected off a DVD. That display of colors you see when looking at a DVD is the spectrum of the light that is reflecting from it. If you would like to use an old CD to make your own instrument to look at spectra, these videos will help:

However, do not look directly at the sun with any device. To view the sun’s spectrum, bounce sunlight off white paper. Otherwise, you will damage your eyes.

The serious study of spectra began near the end of the 18th century. By 1801, experiments had established that the solar spectrum extended beyond visible light and included both the infrared and ultraviolet. In 1802, William Hyde Wollaston (1766-1828) was investigating which primary colors were present in the solar spectrum. His apparatus was somewhat better than those before him. As a result he saw an important detail in the spectrum that others had not seen – dark lines. While Wollaston reported the dark lines, he was interested in the colors in the spectrum, so he did not pursue the lines further.

Wollaston also studied the spectra of light from other sources. He passed light from candles and electrical sparks through the prisms. While doing so, he saw spectra and some bright lines of various colors. But neither he nor his contemporaries pursued an understanding of these spectra.

In 1814, Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787-1826) rediscovered the lines. He cataloged 574 dark lines in the sun’s spectrum. One of the most important was a line he labelled D and was in the yellow portion of the spectrum. He also looked at the spectra of terrestrial lights and noted that these lights had a bright yellow line at the same place as the dark solar D line. During his investigations he discovered that both the dark D lines and the bright yellow line from lamps were really two closely spaced lines (now called a doublet). This was a strong hint that something that was happening with light coming from the sun was similar to something that was happening on light emission on earth. But it would take quite a while for scientists to figure out the connection.

The spectrum below is similar to the one Fraunhofer saw, but this one has been modified to make the dark lines more apparent. It also has many fewer lines than Fraunhofer saw and far fewer than have been discovered now. The labels A, B, and so on were created by Fraunhofer. Today, these lines are called the Fraunhofer lines.

[image error]

(Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

The connection between the dark lines in the solar spectrum and materials on earth would need to continue for quite a while. One line of investigation was the study of light from burning salts. Investigators found that different salts burned with different colors and displayed different spectra. Two significant issues were that many of the spectra were quite complex and that the bright yellow lines corresponding to the Fraunhofer D lines seemed to be in almost all materials.

The idea that Fraunhofer’s lines were connected to processes on earth gained some experimental support. In 1842, Daniel Brewster (1781-1868) reported to the British Association for the Advancement of Science that he had investigated the red spectrum of saltpeter and found that “all the black lines of Fraunhofer were depicted in the spectrum in brilliant red.”

During this same time period the spectra of “electric light” was being investigated. Electric light was created by applying a high voltage to two electrodes of the same metal. The sparks between the electrodes produced light which could be passed through a prism. In this way the spectra of metals could be studied.

Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875), among others, discovered that each metal had a characteristic spectrum. He even set up situations where each of the two electrodes were different metals. Then, he saw the spectra of both metals. However, he missed an important point. About 15 years later, Antoine Masson discovered that the spectrum of electric light contained some common lines independent of the metal as well as those unique to each metal. Masson did not quite carry his investigation far enough, so he also missed an important point.

It fell to Anders Ångström (1814-1874) to discover that the spectrum of an electric light depended on both the metal and the gas surrounding the metal. The common component that Masson saw was the spectrum of air. Thus, Ångström was the first to establish that gases also emitted light that could be analyzed with a prism. As we shall see, these gas emission spectra would prove to be critical to progress in understanding atoms well into the 20th century. (If you did spectral analysis of gases in a chemistry or physics class, you used equipment that was similar to that of Ångström.)

Some spectra with dark lines were also created in the labs. Experimenters would pass full spectrum light through a gas or an arc of an electric light and view the spectrum of the result. Some dark lines would appear.

With all of this information, an adequate explanation of the dark lines in the solar spectrum eluded scientists for about a half of a century. While they suspected that there must be a relation between the dark lines and emission spectra, scientists were hampered because they had no clear model for emission of light and had yet to appreciate fully that each type of atom had a unique spectrum. In fact, some were still arguing about whether atoms exist.

And then that doublet line in the yellow, Fraunhofer’s D, was perplexing. It seemed to be almost everywhere any experimentalist looked.

So, progress was slow, but there was progress. Next time we will look how a physicist and chemist worked together to provide an explanation for this puzzle. Their work would eventually lead to a mathematical formula discovered by a high school math teacher, and in the 20th century, a model of the atom that can be used to derive that formula. It will be a while before we get there because this puzzle has a lot of pieces that we have not looked at yet.

Previously

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

Isaac Newton: 300 Years Ahead of His Time

Issac Newton and the Philosopher’s Stone

When Chemistry and Physics Split

Mme Lavoisier: Partner in Science, Partner in Life

With Atoms, Proportionality and Simplicity Rule

Despite Evidence of Atoms, 19th Century Skeptics Didn’t Budge

Mission of the First International Scientific Conference: Clear up Confusion

Rivalry over the First Periodic Table

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received four major awards — the American Association of Physics Teachers’ Oersted Medal (2014), the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and AAPT’s Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

September 4, 2014

Paganism in Saxony: A Lost Religion

The pagan Continental Saxons make it hard for a novelist. How in the world is she supposed to portray their religion when the Church made every effort to eliminate what it viewed as devil worship? And just to compound things, the Continental Saxons didn’t have a written language as we know it.

Visit A Bit of Mel Time for more about my efforts to reconstruct my characters’ lost religion and while you’re there, sign up for a giveaway of The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar.

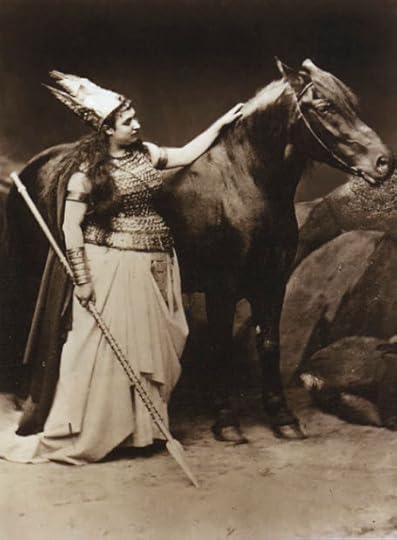

Not exactly the Continental Saxons religion: Wagner’s version of a Germanic pagan religion is seen in an 1876 photo of one of his Ring Cycle operas, with Amalia Materna as Brünnhilde with Cocotte as Grane (public domain photo via Wikimedia Commons).

September 2, 2014

The Challenge of a Medieval Warrior’s Mindset

Let’s face it. When you’re a 21st century, college-educated, middle class American, writing about a common medieval teenage soldier on the battlefield poses a dilemma.

As I wrote The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar and imagined two warriors pointing spears at each other, I was surprised by how impersonal the conflict was, and it struck me again when I read Judith Starkston’s excellent debut, Hand of Fire (to be released September 10 by Fireship Press; read my review on Goodreads). Visit Judith’s blog for my guest post with the title “Nothing Personal, I Just Need to Kill You.”

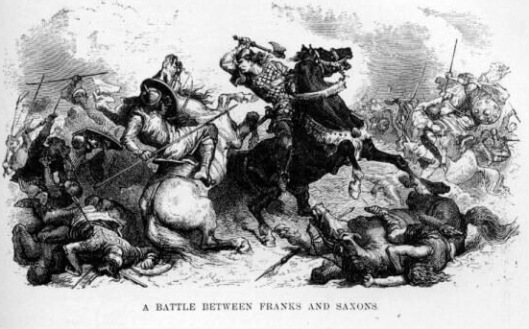

Alphonse de Neuville’s 19th century interpretation of the Franks fighting the Saxons (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

September 1, 2014

Was Charlemagne a Good Guy or a Bad Guy?

In my novels, I have seen the man we today call Charlemagne through different eyes.

In The Cross and the Dragon, my heroine, Alda, thinks he’s a hero, but Leova, the heroine of The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, sees him as a monster. To Fastrada, the protagonist of my work in progress, he is a husband and father.

Oh, what is a writer to do? Visit So Many Book, So Little Time and find out.

A 9th century coin with King Charles’s image (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

August 29, 2014

Early Medieval Times Not Exactly What I Was Taught

Medieval people didn’t bathe. All women were nothing but chattel. You could never have too many sons. Those were only a few misconceptions I had about the early Middle Ages when I first decided to write stories set in the days of Charlemagne.

But when I actually researched the history, a different and more complex picture emerged. For more, read my guest post on Jaffareadstoo for five surprising facts about early medieval times.

A 9th century manuscript (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

August 28, 2014

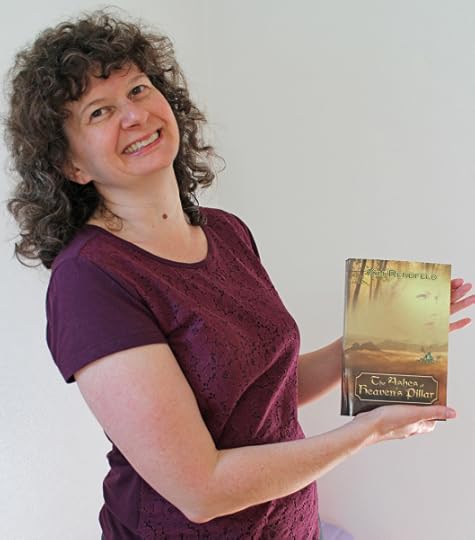

Launch Day: The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar

That moment when the author holds her breath and releases her book baby into the world. Actually, my publisher, Fireship Press, is releasing my book baby into the world. Still, with today’s launch of The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar and the virtual tour to promote it, now you, my readers, get to decide. Will you think it’s beautiful? A worthy companion to The Cross and the Dragon?

Prepublication reviews have called The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, a medieval story of the lengths a mother will go to protect her children, “transportive and triumphant,” “captivating,” and “refreshing.” Jessica Knauss, a good friend and talented author who helped me polish the manuscript, opens her review with “The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar brings Kim Rendfeld’s painstaking research and sensitive psychological drama to some people we never hear about in the history books.”

Still, I’ve been having jitters. After all, every reader sees the book through their own lens. What will readers think as Ashes makes its first stops? Well, here are excerpts:

“The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar is a beautifully written, character-driven story. While the story revolves primarily around Leova and her two children, Rendfeld incorporated a rich cast, which combined with all the historical detail created a compelling and satisfying read.”- Bookworm Brandee

“There is no doubt that the author has a love of early history and uses her considerable knowledge and extensive research to shed light on stories which could all too easily be lost in the mist of time. The historical events sit comfortably alongside a story of loyalty and religious strife and by interweaving historical fact and fiction; a story emerges of a strong family changed by extraordinary historical events.” - Jo at Jaffa Reads Too

“I loved the story. Ms. Rendfeld has done a lot of research and created a wonderful story surrounding a Saxon family as they deal with slavery, heartache and betrayal” – Denise at So Many Books, So Little Time

Want to read it now? The novel is available at Amazon U.S., Amazon U.K., Amazon Canada, and other countries as well as Barnes & Noble. The print version like you see above will appear on these sites soon.

Still deciding? You can read an excerpt and the first chapter at kimrendfeld.com.

You’re invited to follow me on my tour, where more reviewers will offer their insights, I will answer great questions from interviewers and write guests posts, and some of my hosts will offer giveaways in addition to the one under way on Goodreads (click on the widget below to enter).

Goodreads Book Giveaway

The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar

by Kim Rendfeld

Giveaway ends September 09, 2014.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

If you’d like to celebrate the launch with me in person, come to my signing at Books & Brews in Indianapolis from 2-4 p.m. Saturday, August 30, with a sign copy of The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar as a door prize (must be present to win). Books & Brews is a fun place, a used book store for all ages in the front and brewpub that serves tasty beer in the back. I look forward to meeting readers and enjoying a glass of good stout.

August 12, 2014

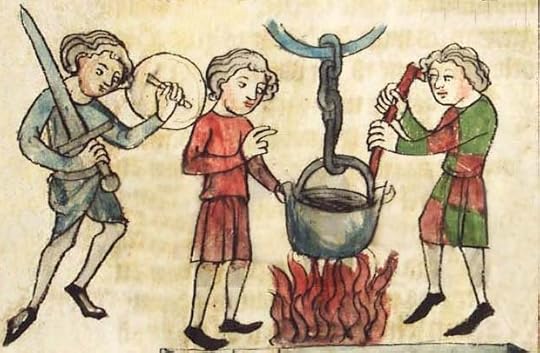

Clues about Medieval Peasants’ Garb

Re-creating what my early medieval peasant characters wore is the result of guesswork. Primary sources from this era were much more concerned with politics and religion than the daily life of their contemporaries.

We can make inferences such as peasants using wool and linen they helped produce, and we have a few clues such as a poem by Theodulf, the bishop of Orleans.

Visit Unusual Historicals for more about what commoners might have worn.

Daily life as depicted in a 9th century Carolingian manuscript (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)