Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 27

February 13, 2014

The Great Hunger Inflames a Hunger to Tell Ancestors’ Stories

Today, I am happy to welcome fellow Fireship Press author Cynthia Neale to Outtakes as she makes a stop in her blog tour to promote Norah: The Making of an Irish-American Woman in 19th-Century New York. Here she explains how The Great Hunger in Ireland spurs a different kind of hunger that may never be satisfied—the one to tell the stories of her ancestors. —Kim

By Cynthia Neale

The hunger to write stories has been within me since I was a young girl. I believed that if I had nothing but books, a notebook, and a pen, I’d be able to survive. I came to this conclusion during long summers in the wilds of upstate New York when Jo in Little Women was my companion and I identified with her hunger to be a writer. I hungered with Pip in Great Expectations to become uncommon and to live beyond groveling limitations.

The hunger to write stories has been within me since I was a young girl. I believed that if I had nothing but books, a notebook, and a pen, I’d be able to survive. I came to this conclusion during long summers in the wilds of upstate New York when Jo in Little Women was my companion and I identified with her hunger to be a writer. I hungered with Pip in Great Expectations to become uncommon and to live beyond groveling limitations.

But little did I know that I also possessed the memory of The Great Hunger, the Irish Famine, within me.

Engraving of Emigrants Leaving Ireland, 1868, Henry Doyle

I studied English literature and struggled to write novels, but it was when I was dancing one evening in an Irish pub and peered at an Irish dresser in a poster that a new hunger made itself known to me.

Where would a young girl in the midst of starvation in Ireland in 1846 go for solace and hope? Where would she go with her own hunger? As I danced, I envisioned the cupboard of an Irish dresser becoming her hiding place and eventually a place of escape to a new land.

As a writer, I knew I needed to write this story. Their story, my story, our story.

After The Irish Dresser, A Story of Hope during The Great Hunger (An Gorta Mor, 1845-1850) was published, I learned there had been a real Norah McCabe who came from Ireland in 1847 to New York City. From that time, I’ve never doubted I’m writing about a real person who once lived on this earth.

I then wrote Hope in New York City, the Continuing Story of the Irish Dresser and thought I was finished with Norah McCabe (and with hunger), but it wasn’t so. It was then I understood on a deeper level, in my genetic makeup perhaps, that the hunger will always be with me. The hunger to tell the story of the Great Hunger of Ireland and to address hunger issues today.

I wrote Norah: The Making of an Irish-American Woman in 19th-Century New York and again thought it was the final book about Norah McCabe. I had already started writing another novel about a Native American woman after years of research. But after a few epiphanies and the advice of my readers, I knew there was yet another novel. My working title is The Irish Milliner and is set during the Civil War period in New York City.

Famine memorial in Dublin

Eaven Boland in an anthology titled Irish Hunger, writes: “The repressed past does not simply let go of us on command. The hidden scar is transmitted, invisibly and unconsciously across generations.” We have become, she says, “‘the present of the past,’ inferring the difference, but unable to feel or know it. We have not healed from these repressed horrors; it is as if unmarked Famine graves are in each of us.”

As a young girl, I did not know my hunger went beyond my need to write and escape a rural childhood, but as I reflect back, I see that hunger manifested itself throughout my life. I baked cookies for the poor country kids in my high school. I went to India to work with the poor and hungry. I worked at soup kitchens, participated in hunger fasts, and had a tea catering business. And I’ve donated a percentage of my book sales to hunger organizations.

I cannot write for the marketplace. I write for the ancestors and for hunger.

Public domain images via Wikimedia Commons.

Cynthia Neale is an American with Irish ancestry and a native of the Finger Lakes region in New York. She now resides in Hampstead, New Hampshire. She is a graduate of Vermont College in Montpelier, with a BA in literature and creative writing. Norah is her first historical novel for adult readers. For more about Cynthia, visit cynthianeale.com.

About Norah: The Making of an Irish-American Woman in 19th-Century New York

Once she was a child of hunger, but now Norah McCabe is a woman with courage, passion, and reckless dreams. Her story is one of survival, intrigue, and love. This Irish immigrant woman cannot be narrowly defined! She dons Paris fashion and opens a used-clothing store, is attacked by a vicious police commissioner, joins a movement to free Ireland, and attends a National Women’s Rights Convention. And love comes to her slowly one night on a dark street, ensnared by the great Mr. Murray, essayist and gang leader extraordinaire. Norah is the story of a woman who confronts prejudice, violence, and greed in a city that mystifies and helps to mold her into becoming an Irish-American woman.

Once she was a child of hunger, but now Norah McCabe is a woman with courage, passion, and reckless dreams. Her story is one of survival, intrigue, and love. This Irish immigrant woman cannot be narrowly defined! She dons Paris fashion and opens a used-clothing store, is attacked by a vicious police commissioner, joins a movement to free Ireland, and attends a National Women’s Rights Convention. And love comes to her slowly one night on a dark street, ensnared by the great Mr. Murray, essayist and gang leader extraordinaire. Norah is the story of a woman who confronts prejudice, violence, and greed in a city that mystifies and helps to mold her into becoming an Irish-American woman.

February 7, 2014

When Chemistry and Physics Split

Time for another post about the history of atom theory from award-winning physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman. Today, we meet 18th century scientists who were unsatisfied with the idea that forces acted on particles and came up with alternatives to explain their observations. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

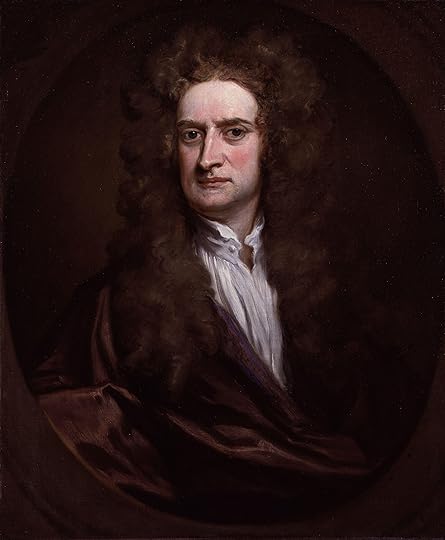

As we have discussed in the previous two posts, Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) had many ideas correct in his model of matter. Perhaps most importantly, he concluded that the particles of matter which were too small to see interacted via forces. Further, these forces decreased in strength as the particles moved further away from each other.

As we have discussed in the previous two posts, Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) had many ideas correct in his model of matter. Perhaps most importantly, he concluded that the particles of matter which were too small to see interacted via forces. Further, these forces decreased in strength as the particles moved further away from each other.

Today’s models of matter have several types of particles and four different forces. However, Sir Isaac’s model was pointing in the right direction. Yet, as we shall see, the idea of small particles interacting via forces lost favor with researchers, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries. In this post, we will look at some of the reasons.

Portrait of Sir Isaac Newton, Godfrey Kneller, 1702

By Newton’s time, and somewhat because of Newton, scientists were expecting quantitative explanations to natural phenomena. So, several people attempted to use Newton’s ideas to calculate observed results. For example, Newton tried to derive Boyle’s Law involving gases by using forces that decrease in strength as the particles moved further away. In the preface to the Principia, Newton lamented that while he was able to determine orbits of planets, he could only wish that he “could derive the rest of the phenomena of nature by the same kind of reasoning.”

Several others attempted various types of calculations. Some involved large numbers of different types of forces or sizes of particle; some even used different sizes of spaces between the particles. Nothing was considered very successful.

In 1744, Pieter van Musschenbroek (1692-1761), a well-known researcher in electrical phenomena, wrote, “Though there may be several internal principles acting in bodies in different proportions at different distances yet it is impossible to determine them.” Thus, many in the scientific community felt that trying to understand matter by using forces between small particles was not productive.

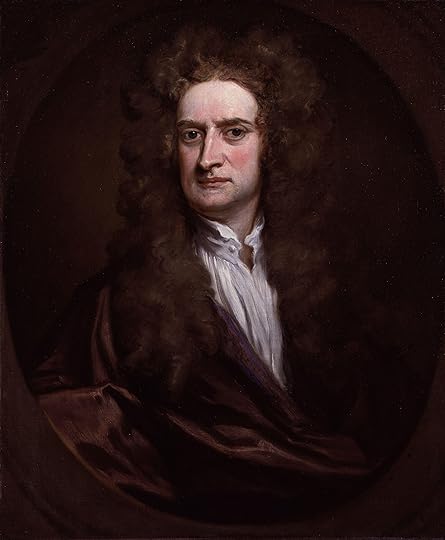

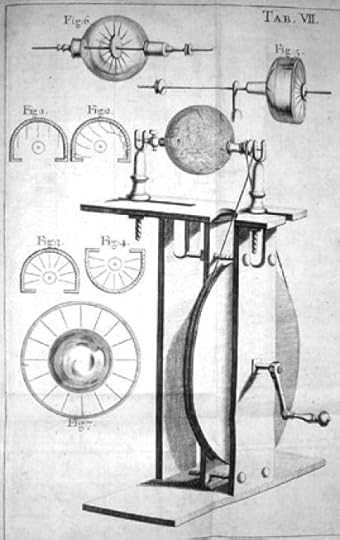

Generator built by Francis Hauksbee. From Physico-Mechanical Experiments, 2nd Ed., London 1719

At the same time, other ideas were taking hold that did seem productive, at least on the short run. Francis Hauksbee (1660-1713) discovered that heat and electricity could pass through a glass container that had the air removed from it. This observation led Newton to speculate that all of space was filled with an undetectable material that was the medium for the transmission of things like heat and electricity. This idea in turn gave rise to a concept that heat and electricity, among other phenomena, were themselves some type of liquid. When an object increased in temperature, a fluid flowed into it. Likewise, objects with positive electric charge had gained some type of invisible fluid. (A small aside: The idea of two types of electricity was first described by Benjamin Franklin, who was better known as a politician and womanizer.)

While these fluids were not consistent with our modern models, they allowed the scientists of the 18th century to be more quantitative than they could be with Newton’s forces acting on the small objects in matter. Thus, they became popular.

Meanwhile, chemists were finding ways to deal with their new experimental results. A German chemist, Georg Ernst Stahl (1659-1734), proposed that chemists use the properties of chemical elements to try to explain their observations. (The word element was not used then, but it is an easy way to get the idea across.) The properties of substances made of more than one element could be determined by the constituents of the substance. This type of effort led to chemists being able to “understand” how different chemicals combine. Because it proved quite useful in the laboratory, this approach displaced using forces to try to explain chemical reactions.

Meanwhile, chemists were finding ways to deal with their new experimental results. A German chemist, Georg Ernst Stahl (1659-1734), proposed that chemists use the properties of chemical elements to try to explain their observations. (The word element was not used then, but it is an easy way to get the idea across.) The properties of substances made of more than one element could be determined by the constituents of the substance. This type of effort led to chemists being able to “understand” how different chemicals combine. Because it proved quite useful in the laboratory, this approach displaced using forces to try to explain chemical reactions.

Thus, chemistry and physics went separate ways. Physicists went in the direction of trying to understand heat, electricity, magnetism, and other macroscopic phenomena (and eventually dumped the ideas of invisible fluids). Chemists studied the behavior of gases, chemical reactions, and so forth. These chemical studies did lead to a greater understanding of the small objects that make up matter. So, we will start taking a closer look at them next time.

Images via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Previously

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

Isaac Newton: 300 Years Ahead of His Time

Issac Newton and the Philosopher’s Stone

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received four major awards — the American Association of Physics Teachers’ Oersted Medal (2014), the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and AAPT’s Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

January 29, 2014

When Regency Boys Outgrow Dresses, It’s Time for Skeleton Suits

It’s my pleasure to welcome Maria Grace back to Outtakes as she promotes her latest title, Twelfth Night at Longbourn, the fourth volume in the Given Good Principles series, a story about Kitty Bennet. Today, part two of two, Grace tells us about what boys wore when they outgrew their dresses. See yesterday’s post to learn what boys wore as infants and toddlers. – Kim

By Maria Grace

During the Regency, the point at which little boys stopped wearing dresses was called breeching and accompanied by a family ceremony.

During the Regency, the point at which little boys stopped wearing dresses was called breeching and accompanied by a family ceremony.

Most boys were breeched about 4 years of age, several years earlier than their counterparts from the 1700s. Child rearing “experts,” though, argued for various ages, up to age 8. They agreed though that a child’s size was a most important consideration. Boys who were small for their age or sickly might be breeched later. On the other hand, boys might be breeched earlier if there was concern that a parent might not live to see their son breeched.

Mothers were primarily responsible for the decision for their sons to be breeched. Fathers might exert some pressure, though, if the mother delayed the event too long.

Social class and standing would greatly influence the nature of the breeching ceremony. For the family with little means, it might be a simple affair or receiving hand-me-downs from an older brother. For the aristocracy, it might be an elaborate affair.

Exhibit in the Patricia Harris Gallery of Textiles & Costume, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto

During the Regency, the ceremony rarely took place on the little boy’s birthday. Rather, the convenience of extended family to attend the event might be the deciding factor for timing. If the child was the heir of an upper class family, the ceremony was likely to take place at the family’s country estate rather than in a town home. Extended family and close friends, like the child’s godparents, would be invited to attend.

In preparation for the ceremony, a mother would have at least one new suit of clothes made, assuming she had the means. Otherwise, hand-me-downs might be refreshed for the boy. Cotton or linen shirts, sashes, formal garments, and outerwear might also be acquired. Accessories like hats, gloves, stockings, and shoes could round out a little boy’s new wardrobe.

No single form existed for the breeching ceremony. Family and friends present, the little boy would make an appearance in his dress, then be led away behind a screen or to another room to change, with assistance, into his first set of distinctive male clothing. In some cases a barber might be present to give him his first masculine haircut. The shorn curls might be given to attendees as mementoes of the event.

Refreshments would be served when the newly minted young man returned in his new clothes. Well-wishers might slip coins or banknotes into his pockets as they congratulated him on his new status.

Skeleton Suits

A skeleton suit, one of those straight blue cloth cases in which small boys used to be confined before belts and tunics had come in … An ingenious contrivance for displaying the symmetry of a boy’s figure by fastening him into a very tight jacket, with an ornamental row of buttons over each shoulder and then buttoning his trousers over it so as to give his legs the appearance of being hooked on just under his arm pits. (Charles Dickens, Sketches by Boz, 1838-39.)

The Basket of Cherries, by E.W. Gill, 1828

At the end of the 1700s upper and middle class boys typically wore a skeleton suit after they were breeched and would continue in these garments until around the age of 11. These suits featured a high button waist, long pantaloons, rather than the knee breeches worn by older men, and jackets adorned with many buttons. A blouse with an open, often elaborate collar was worn under the jacket which might be buttoned to the pants to help hold them up. Young boys might also wear pantalettes underneath with a trim or frills showing at the ankles.

Skeletons suits were cut close to the body but with far more ease in the cut than the skin tight breeches and coats worn by men. Thus, though boys today would likely find them very uncomfortable, boys of the era would consider them neither tight nor constricting.

The blouses for the suits were typically white and made of linen or cotton. For every day wear, the pants and jackets might be made of yellow-brown nankeen or other sturdy washable fabrics. Into the 19th century, improved dyeing techniques allowed fabrics to be more colorfast, thus more colorful skeleton suits appeared. During the Regency, dark blue was a favorite color, especially for more formal suits made of silks or velvet.

By Antonio Carnicero, circa 1798-1802

On special occasions, boys might wear a round straw hat with a brim, and a wide ribbon band or a military style cap. Colorful sashes might also be added to the skeleton suits, tied in large poufy bows around the waist or over the shoulder. To finish their ensemble, boys would wear plain white stockings and flat shoes with a single strap over the instep, typically in black.

Little boys were permitted more latitude in their dress than adult men, particularly when out of the public eye. At times they were permitted to go without the jacket, presumably with some other mechanism to help hold up their pants. Some sources suggest some suits had midcalf length trousers and short or no sleeves. These were likely reserved for country wear, especially during warmer weather. It is also possible that in summer, skeleton suits might be worn without a shirt at all on very informal occasions.

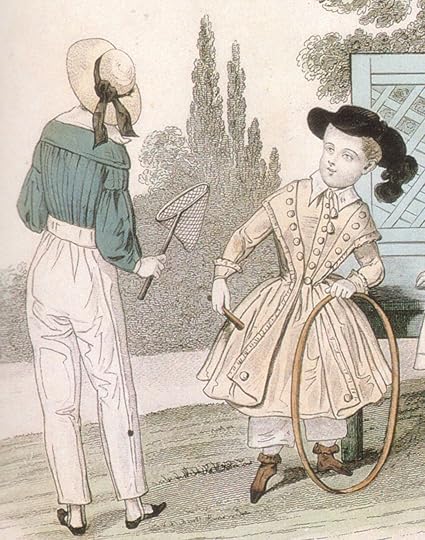

Detail of fashion plate from Petit Courier des Dames, 1841

A fashion conscious mother could keep up with trends in children’s clothing starting in a 1779 edition of the Lady’s Magazine, which devoted a small section to children’s clothes. These fashion plates started with girls’ clothes only, but by the Regency, boy’s clothes were included as well, since the same seamstresses who made ladies’ clothes also made little boy’s clothes. Children’s fashion illustrations did not appear frequently though. This irregularity had the effect of slowing the pace of change of children’s clothing, since there were fewer references available for new designs.

By 1840, skeleton suits were considered old fashioned and fell out of favor. However, their popularity as children’s wear influenced men’s fashion in the following years. Since the boys who wore skeleton suits did not associate long trousers with working class garb as their fathers did, but rather with comfortable clothing for both casual and formal wear, when they came of age, they did not want to trade in their comfortable trousers for the skin tight, restrictive knee breeches their fathers wore. So trousers rose in status and esteem, and breeches slowly fell out of fashion.

Previously: Boys in dresses and other quirks of Regency children’s fashions.

Public domain images via Wikimedia Commons

References

“A Lady of Distinction,” Regency Etiquette, the Mirror of Graces (1811). R.L. Shep Publications (1997)

Barreto, Cristina and Lancaster, Martin. Napoleon and the Empire of Fashion. Skira (2010)

Brooke, Iris. English Children’s Costume 1775-1920. Dover Publications Inc. (2003)

Davidoff, Leonore and Hall, Catherine. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class 1780-1850. Routledge (2002)

Dickens, Charles. Sketches by Boz (1838-39)

Kane, Kathryn. “Of Hanging Sleeves and Leading Strings,” Regency Redingote. January 20, 2012

Kane, Kathryn. “Regency Baby Clothes: Blue for Boys, ??? for Girls,” Regency Redingote. June 8 2012

Kane, Kathryn. “Boy to Man: The Breeching Ceremony,” Regency Redingote. August 31, 2012

Kane, Kathryn. “Portent of Pantaloons: The Skeleton Suit,” Regency Redingote. April 27, 2012

Kelly, Ian. Beau Brummell, The Ultimate Man of Style. Free Press (2006)

Sanborn, Vic. “The well-dressed Regency boy wore a skeleton suit,” Jane Austen’s World. August 17, 2009

Selbie, Robert. The Anatomy of Costume. Crescent Books (1977)

Selwyn, David. Jane Austen and Children. Continuum Books (2010)

Shoemaker, Robert B. Gender in English Society 1650-1850. Pearson Education Limited (1998)

Though Maria Grace has been writing fiction since she was 10 years old, those early efforts happily reside in a file drawer and are unlikely to see the light of day again, for which many are grateful. She has one husband, two graduate degrees and two black belts, three sons, four undergraduate majors, five nieces, six cats, seven Regency-era fiction projects, and notes for eight more writing projects in progress. To round out the list, she cooks for nine in order to accommodate the growing boys and usually makes 10 meals at a time so she only cooks twice a month.

Though Maria Grace has been writing fiction since she was 10 years old, those early efforts happily reside in a file drawer and are unlikely to see the light of day again, for which many are grateful. She has one husband, two graduate degrees and two black belts, three sons, four undergraduate majors, five nieces, six cats, seven Regency-era fiction projects, and notes for eight more writing projects in progress. To round out the list, she cooks for nine in order to accommodate the growing boys and usually makes 10 meals at a time so she only cooks twice a month.

Connect with her by e-mail at author [dot] MariaGrace [at] gmail [dot] com, Facebook at facebook.com/AuthorMariaGrace, Amazon at amazon.com/author/mariagrace, her website Random Bits of Fascination, and Twitter @WriteMariaGrace.

January 28, 2014

Little Boys in Dresses? Typical Apparel in the 1800s

It’s my pleasure to welcome Maria Grace back to Outtakes as she promotes her latest title, Twelfth Night at Longbourn, the fourth volume in the Given Good Principles series, a story about Kitty Bennet. Today, part one of two, Grace introduces us to young boys’ apparel, which included dresses. Tomorrow, Grace will tell us about what boys wore when they outgrew those dresses. – Kim

By Maria Grace

Along with the political and social changes of the 1800s, dramatic changes in fashion ushered in the turn of the century as well. These changes not only encompassed adult styles, but the clothes worn by children saw large alterations, moving away from stiff and restrictive imitations of adult fashions to much freer, more comfortable clothing conducive to play. Two of the most distinct changes were dresses for little boys and skeleton suits for slightly older boys.

Along with the political and social changes of the 1800s, dramatic changes in fashion ushered in the turn of the century as well. These changes not only encompassed adult styles, but the clothes worn by children saw large alterations, moving away from stiff and restrictive imitations of adult fashions to much freer, more comfortable clothing conducive to play. Two of the most distinct changes were dresses for little boys and skeleton suits for slightly older boys.

Infant Clothes

By Fritz von Dardel, 1843

During the Regency, the majority of garments for infants and babies, whether swaddling bands for the first few months of life or simple gowns worn thereafter, were typically linen or cotton, either white or unbleached natural color cloth, possibly trimmed with colored ribbons. These ribbons would be chosen to the mother’s tastes, not restricted to blue for boys and pink for girls as would be seen much later in the century.

In wealthier families, babies had some “good” clothes to wear while being shown off to visiting family and friends. Typically these garments would be colored or trimmed in ways that would not stand up as well to the harsh laundry techniques of the day, so they would be worn sparingly.

During this era, parents felt little need to identify a small child’s gender by their clothing. Those personally acquainted with the family would already know the child’s gender, and for those who did not know the family that well, it was none of their business. Moreover, very young children rarely appeared in public. The age at which children began to be seen outside the house coincided with the age at which they would begin to wear gender differentiated clothing.

Family portrait Anna Ivanovna Tolstoy, by Angelica Kauffman, 1790s

One distinctive feature of infant clothing still present in the early 1800s was leading strings. Leading strings were the fashion decedents of the hanging sleeves of the Middle Ages. They were attached to the back of children’s garments when the child began to move independently.

Leading strings might be sewn into individual garments when a family could afford multiple sets. For those of lesser means a single set could be pinned onto different garments. They could be used as a horse’s reins to guide the child during the process of learning to walk. This approach was most prevalent in the upper classes.

For middle and lower class women who enjoyed less help from servants, leading strings might be used more as a leash to limit a child’s movement. The strings could be fastened to a bed-post or heavy piece of furniture while indoors or something immobile like a fence or tree while outside.

Though this might be an uncomfortable idea to modern parents, in a world where child safety measures were largely nonexistent, these methods could help keep a child safe while their mother’s attention was diverted elsewhere. Leading strings were usually removed when children learned to walk well, certainly by age 3 or 4.

Boys in Dresses

Portrait of William Henry Meyrick, by John Hoppner, c. 1793

Before learning to walk, babies wore long gowns that extended beyond their feet. Once out of infancy (walking age), both boys and girls were “shortcoated,” clothed in ankle length dresses. The early 19th century saw almost no difference between dresses for little boys and little girls. Little boys might wear their sisters’ hand-me-downs and vice-versa. Dresses might be made of chintz or printed cottons. They were worn with small white caps, sashes and petticoats or long ruffled pantaloons.

Though it is difficult for the modern observer to wrap their minds around dressing little boys like little girls, the fact was that dresses were considered children’s wear, not little girls’ clothes. Children’s dresses were distinct from women’s garments, so to the eye of the person in context, it was not a matter of boys in women’s garments. On a more practical note, in the days before disposable diapers and washing machines, dresses were much more practical garments for children who were not toilet trained.

Tomorrow: When boys outgrow their dresses and are old enough to be breeched.

Public domain images via Wikimedia Commons

References

“A Lady of Distinction,” Regency Etiquette, the Mirror of Graces (1811). R.L. Shep Publications (1997)

Barreto, Cristina and Lancaster, Martin. Napoleon and the Empire of Fashion. Skira (2010)

Brooke, Iris. English Children’s Costume 1775-1920. Dover Publications Inc. (2003)

Davidoff, Leonore and Hall, Catherine. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class 1780-1850. Routledge (2002)

Dickens, Charles. Sketches by Boz (1838-39)

Kane, Kathryn. “Of Hanging Sleeves and Leading Strings,” Regency Redingote. January 20, 2012

Kane, Kathryn. “Regency Baby Clothes: Blue for Boys, ??? for Girls,” Regency Redingote. June 8 2012

Kane, Kathryn. “Boy to Man: The Breeching Ceremony,” Regency Redingote. August 31, 2012

Kane, Kathryn. “Portent of Pantaloons: The Skeleton Suit,” Regency Redingote. April 27, 2012

Kelly, Ian. Beau Brummell, The Ultimate Man of Style. Free Press (2006)

Sanborn, Vic. “The well-dressed Regency boy wore a skeleton suit,” Jane Austen’s World. August 17, 2009

Selbie, Robert. The Anatomy of Costume. Crescent Books (1977)

Selwyn, David. Jane Austen and Children. Continuum Books (2010)

Shoemaker, Robert B. Gender in English Society 1650-1850. Pearson Education Limited (1998)

Though Maria Grace has been writing fiction since she was 10 years old, those early efforts happily reside in a file drawer and are unlikely to see the light of day again, for which many are grateful. She has one husband, two graduate degrees and two black belts, three sons, four undergraduate majors, five nieces, six cats, seven Regency-era fiction projects, and notes for eight more writing projects in progress. To round out the list, she cooks for nine in order to accommodate the growing boys and usually makes 10 meals at a time so she only cooks twice a month.

Though Maria Grace has been writing fiction since she was 10 years old, those early efforts happily reside in a file drawer and are unlikely to see the light of day again, for which many are grateful. She has one husband, two graduate degrees and two black belts, three sons, four undergraduate majors, five nieces, six cats, seven Regency-era fiction projects, and notes for eight more writing projects in progress. To round out the list, she cooks for nine in order to accommodate the growing boys and usually makes 10 meals at a time so she only cooks twice a month.

Connect with her by e-mail at author [dot] MariaGrace [at] gmail [dot] com, Facebook at facebook.com/AuthorMariaGrace, Amazon at amazon.com/author/mariagrace, her website Random Bits of Fascination, and Twitter @WriteMariaGrace.

January 22, 2014

Overwhelmed by Choice: Writing about a Medieval Pilgrim’s Day

“A Day in the Life” should be an easy thing for a historical novelist to write about. After all, the very thing we research is the daily routine of the era. But when it came to writing about a day in the life of an eighth-century pilgrim, a lot of variables appeared before me.

Where does the day start? In a city? An abbey? The woods? And where does it end? The aforementioned city, abbey, or woods? How about a village or an estate?

And whose day is it? A woman desperate for a child? A man hoping a saint will cure him of the chronic coughs that sometimes cause him to spit up blood? A teen girl who hears voices that tell her to set her home on fire? An old priest wanting to atone for sins and spend less time in Purgatory? A man who murdered someone in a fight in a tavern?

And what social class is this pilgrim? An aristocrat has different transport, companions, and lodging than a commoner.

Finally, I settled on a character I had already created for The Cross and the Dragon and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar (forthcoming), Sister Elisabeth, who has heard about the afterlife for all 50 of her years and would like to spend less time in Purgatory, perhaps even avoid it. Read my post at Unusual Historicals for what a day in medieval pilgrim’s life was like.

The Pilgrimage to Canterbury by Thomas Stothard, 1806-7

January 17, 2014

Saint Ursula: Inspiring Generations

St. Ursula and her companions, from the Reliquary of St. Ursula Hans Memling, 1489

In eighth century Francia, the setting for my novels The Cross and the Dragon and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, believers would have known virgins were martyred in Cologne for their faith.

After that, what version the Franks would have heard is unclear. One ninth century martyrology has several women; another has several thousand. It isn’t until the 11th century that a fuller version of the story of the British-born Saint Ursula emerges, with a lot of fantastic elements: 11,000 virgins, a pope who abdicates, an army of martyrs. Even the Catholic Encyclopedia has used the term “fables” to describe the events.

Regardless of what particular details of Ursula’s story are true, a courageous group of women faced death rather than betray their faith, and their story has inspired generations. Visit English Historical Fiction Authors for more about this fascinating saint.

January 10, 2014

A Conspiracy Theory about a Martyred Pope

While researching an upcoming post about Saint Ursula and her companions, I came across a conspiracy theory involving why there are no official records of a medieval pope martyred in Cologne.

The arrival of St. Ursula and her companions in Rome to meet Pope Cyriacus, from the Reliquary of St. Ursula, Hans Memling, 1489

According to legend, Ursula and her companions – including 11,000 virgins – visited Rome on their pilgrimage and met Pope Cyriacus. The pagans in Ursula’s group were baptized. Moved by a vision of an army of martyrs, he relinquished the papacy to follow Ursula and her group and was slaughtered with them in Cologne.

Problem is, Pope Cyriacus appears only in this legend. Conspiracy theorists say that the cardinals were so angry, they erased his name from the books.

It sounds like an easy job. Because of the expense, books in early medieval Europe were rare and precious. With few people who knew how to read, let alone write, information about early medieval times can be scarce. But in my research about the Carolingian era, a few centuries after Ursula died, evidence of a pope’s existence is not confined to documents in Rome. We have mentions in annals and surviving letters.

So the conspirators must have done a thorough job. In an age where messages took weeks to deliver, they would have had to hunt down monasteries and Christian kings to wipe out any trace of Cyriacus’s existence.

The story of Cyriacus is not the only invention in the legends about Ursula. Even the Catholic Encyclopedia has used the word “fables” when recounting the details. But Ursula’s story is still worth sharing because at its core is a tale of courage that has inspired generations. More about Ursula next time.

Sources

“St. Ursula and the Eleven Thousand Virgins,” Albert Poncelet. The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15.

St. Ursula and the Eleven Thousand Virgins of Cologne: Relics, Reliquaries and the Visual Culture of Group Sanctity in Late Medieval Europe, Scott B. Montogomery

January 3, 2014

Isaac Newton and the Philosopher’s Stone

Time for another installment in the series about atom theory by physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman. Here, we’re with Isaac Newton at a time when alchemy was mainstream science. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

In addition to Isaac Newton’s work in mathematics and physics, he conducted a large amount of work in alchemy. Many historians believe that he spent more time completing alchemical experiments than he did on all of the science for which he is famous today.

In addition to Isaac Newton’s work in mathematics and physics, he conducted a large amount of work in alchemy. Many historians believe that he spent more time completing alchemical experiments than he did on all of the science for which he is famous today.

Today, alchemy is frequently considered an occult undertaking that was driven by greed and superstition. However, that view is the result of interpreting the alchemists’ work in light of our 21st century understanding of matter. We know that converting lead or iron into gold through some chemical means is not possible. However, we know this conversion is not possible because we understand that each of the metals is an element made of atoms. We cannot change the atoms of one element into those of another with chemistry. (Nuclear physics is a different story, but we will save it for much later.)

The Alchymist, In Search of the Philosopher’s Stone, Discovers Phosphorus, and prays for the successful Conclusion of his operation, as was the custom of the Ancient Chymical Astrologers, by Joseph Wright of Derby, 1771

In Newton’s time (and long before) philosophers believed that all metals were composed of mercury and sulfur. Some philosophers added salt as a fundamental constituent. Each of the metals such as iron, lead, and gold were mixtures of these two or three fundamental components. Thus, the goal of the alchemist was to find the way to change the mixture found in lead or iron into the mixture found in gold. The substance that could accomplish this was called the Philosopher’s Stone. (A nice overview of alchemy and some contemporary historical research about it can be found at Discover magazine.)

An important player in developing the alchemical view of matter was a 13th century writer and experimentalist called Geber. The name seems to be a pseudonym and is apparently a Latinized version of the name of an 8th century scientist, Jābir ibn Hayyān. Geber’s identity is still somewhat disputed, but evidence is pointing toward a Franciscan monk from southern Italy. More important than his identity, Geber developed a corpuscular theory of matter which became the foundation for much of alchemy.

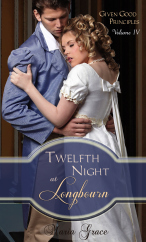

Daniel Sennert

Closer to Newton’s time a German professor, Daniel Sennert, performed a critical experiment. Sennert dissolved precious metal in acids. The solution which he obtained did not look at all like the metal. In fact, any observer could conclude that the resulting liquid had no metal in it. Prior to Sennert’s experiments most people would conclude that the metal had disappeared. But Sennert then used chemicals to precipitate the original metal out of the solution. A sensible conclusion was that the metal was in the somehow in the solution even though it was not visible. These types of experiments led Sennert to build on Geber’s ideas for a corpuscular model for matter.

Sennert’s experiments had a profound influence on Robert Boyle, who is commonly considered the father of modern chemistry. In Atoms and Alchemy, William Newman states that Boyle “borrowed” Sennert’s ideas “almost verbatim” in his first paper on atomism.

Likewise, historians in recent years have seen much similarity between some of Sennert’s ideas and some of Newton’s. For example, Sennert’s models include attraction between corpuscles with different affinities for different substances. So does Newton’s.

Portrait of Sir Isaac Newton, Godfrey Kneller, 1702

How much influence the alchemists had on Newton and his ideas about matter are still being sorted out. Newton read much about alchemy. He wrote many documents about his experiments but did not publish them. Some historians estimated that Newton’s writings on alchemy exceed a million words. So he clearly was aware of the alchemistic viewpoint. And at this time, the alchemists had developed a well-founded corpuscular model of matter. This work plus that of Newton and Boyle put the concept of small units of matter which make up everything on rather firm footing.

Independent of what influenced Newton’s and Boyle’s view of matter, the time after their discoveries began some fast moving changes in humankind’s understanding of the objects that we cannot see. More on that next time.

Images via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Previously:

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

Isaac Newton: 300 Years Ahead of His Time

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received four major awards — the American Association of Physics Teachers’ Oersted Medal (2014), the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and AAPT’s Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

December 23, 2013

Child’s Play: Preparation for a Warrior’s Life

When we shop for toys for the loved ones on our list, we like to think the kids learning something. Books help children learn to associate those squiggles with objects. Puzzles help them solve problems. Dolls engage the imagination.

13th century bronze toy knight (from Walters Art Museum via Wikimedia Commons)

In eighth century Francia, the setting for The Cross and the Dragon and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, the nobility had their own idea of educational toys. For boys, it included wooden swords and toy soldiers of bronze, silver, or gold. The purpose of these toys was not just to indulge fantasy. Their parents fully expected their sons to soon be wielding real swords and leading conscripts into battle.

See my post on Unusual Historicals for more about how noble-born boys’ early childhood was part of their preparation to become warriors.

December 18, 2013

The Insulted Princess: Charlemagne’s Second Wife

Sculptures of martyrs in the Lombard Temple show what women might have worn (from Wikimedia Commons)

All we can say with certainty about King Charles’s (Charlemagne’s) second wife is that she was a Lombard princess, the daughter of King Desiderius and Queen Ansa, and that she was married to the Frankish king for about a year (770-71).

We don’t even know for certain what her name was. Because of a misreading of a medieval book, she has been called Desiderata, but scholarship from historian Janet L. Nelson indicates her name might have been Gerperga.

Yet what little we know of her illustrates what was expected of an aristocratic woman, particularly a royal one, in eighth century Europe.

Desiderius and Ansa apparently had one son and four daughters. They expected their son, Adalgis, to succeed his father as king. Before Desiderius seized power in a coup in 756, his eldest daughter, Anselperga, became an abbess. Not a bad gig for a medieval woman, who could treat the abbey as her fiefdom and still have an influence on worldly affairs. In addition, prayers from her abbey would help ensure that God was on her family’s side.

After he became king, Desiderius and Ansa made sure their other daughters’ marriages were politically advantageous to their realm in northern Italy. Princess Adelperga married the duke of Benevento in southern Italy, and Princess Luitperga married the duke of Bavaria, King Charles’s first cousin, whose territory was to Lombardy’s northwest.

Exactly who initiated marriage negotiations to have Charles marry Gerperga is unknown, but it had the full support of Desiderius and Charles’s widowed mother, Bertrada.

Bertha Broadfoot, 1848, by Eugène Oudiné at Luxembourg Garden, Paris. (copyrighted photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons).

A letter bearing Pope Stephen’s name shows a man very upset that a Frankish king, either Charles or his brother, Carloman, might marry the daughter of his political enemy. Frankish Queen Mother Bertrada went on a diplomatic mission to ensure peace between her sons, reassure the pope that it would be in Rome’s best interest to allow the marriage to go through, then go to Lombardy and return to Francia with the princess.

As is common in medieval marriages, Gerperga likely would have been a teenager. Technically, a woman had to consent to a marriage, but that consent could be beaten or starved out of someone. It is easy to say these women were pawns, but their position is more complex than that.

For one thing, a father, or a mother acting as regent, could just as easily order a son’s marriage. Charles and Carloman were already married on their father’s order, something the pope points out in his outraged letter arguing against a Frankish royal marriage to a Lombard. Desiderius wanted Adalgis to marry Charles’s sister, but that idea was nixed on the Frankish side.

Another thing to consider is when a character in a historical novel complains of a “useless girl,” he is mistaken. In arranging their children’s marriages, Desiderius and Ansa did not consider the girls useless. They relied on the three who were married to secure alliances, two of them close to Lombardy. Even after Desiderius lost his kingdom, there is evidence of the princesses’ influence as wives. In later years, Luitperga would be accused of encouraging her husband’s disloyalty to Charles, and Adelperga would temporarily assume power in Benevento after her husband’s and elder son’s deaths.

We have no clue of how any of these women, including Gerperga, felt about the choices their parents had made for them. Was Gerperga happy her father had chosen a 22-year-old, tall, and broad with muscle rather than an old man? Did she have any misgivings that Charles was setting aside a Frankish woman to marry her? Did she marry him because of a sense of duty to her country?

Just as Gerperga’s marriage was created by politics, so was it destroyed. King Carloman died at age 20 in December 771, and Charles seized his brother’s lands, even though Carloman had two young sons. To solidify his place as king of all Francia, he repudiated the Lombard princess and married a young woman from an important family in Carloman’s former kingdom.

To Desiderius, the repudiation of his daughter was an insult, and it might have been one reason he sided with Carloman’s widow, Gerberga, when she sought his aid to have her sons anointed as Frankish kings. The war that followed in 773-74 was a high stakes family feud involving the fate of Rome. (For more on Charles’s war in Lombardy, see my previous posts in Unusual Historicals and Historical Fiction Research).

The ultimate fate of Charles’s second wife remains a mystery. A 16th century writer using a now-lost 8th century document calls her Berchthraeda and says she was sent home gravely ill and died in childbirth, bearing a son. He also says Charles married someone to whom he had been previously betrothed, and there’s not much evidence of that.

The Royal Frankish Annals say an unnamed Lombard princess was captured, along with Desiderius and Ansa, when Pavia fell in 774 after a long siege, but they are silent on what happened to her afterward. If Gerperga was captured in Pavia, it is possible that she wound up in a cloister, the repository for many of Charles’s troublesome relatives.

Sources

After Rome’s Fall: Narrators and Sources of Early Medieval History, edited by Walter A. Goffart, Alexander C. Murray, University of Toronto Press, 1998 “Chapter 9: Making a Difference in Eighth-Century Politics: The Daughters of Desiderius,” Janet L. Nelson, pp. 171-190

Charlemagne: Translated Sources, P.D. King

Carolingian Chronicles, Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories, translated by Bernhard Walter Scholtz with Barbara Rogers