Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 28

December 13, 2013

Lombard Sculptures Provide Clues to the Past

From Wikimedia Commons

While looking for artwork to accompany a future post about Charlemagne’s second wife, I came across this photo of stucco sculptures in the Lombard Temple (associated with the Santa Maria in Vallee Monastery) in Fruili, Italy. None of these women is the Lombard princess Frankish King Charles repudiated. Instead, they represent holy martyrs.

So why use a photo of these women? Images of the Lombard princess are hard to come by; we don’t even know with certainty what her name was. The temple these sculptures reside in dates back to the eighth century, about the same time as the princess, and according to a caption of a similar photo in Wikimedia Commons, these sculptures above an eighth-century fresco are from the same period. Medieval artists clothed their characters in contemporary garb no matter what century the event happened. The clothing on the sculptures, rendered in beautiful detail, is consistent with Frankish fashion from this era – long loose sleeves over tighter sleeves, girdles, underskirts.

Might the Lombard princess have worn something like the clothing and headdresses shown here and styled her hair in a similar way? Might she have similar facial features? The sculptures give us tantalizing clues.

Related Link

Tempietto Longobardo (English version)

December 6, 2013

Isaac Newton: 300 Years Ahead of His Time

Time for another post about the history of atom theory from award-winning physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman. Today, we meet one of the giants of science history, Isaac Newton. Not only did his work introduce new theories and discoveries; he also set the stage for the future. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

At the Royal Society’s celebration of the 300th anniversary of Isaac Newton’s birth, Niels Bohr said, “Truly, it may be stated that Newton’s genius did not only bring order to all knowledge attainable at his time, but even led him to an amazing degree to anticipate later discoveries and developments.” This statement can be supported in a variety of topics including the models of the composition of matter.

At the Royal Society’s celebration of the 300th anniversary of Isaac Newton’s birth, Niels Bohr said, “Truly, it may be stated that Newton’s genius did not only bring order to all knowledge attainable at his time, but even led him to an amazing degree to anticipate later discoveries and developments.” This statement can be supported in a variety of topics including the models of the composition of matter.

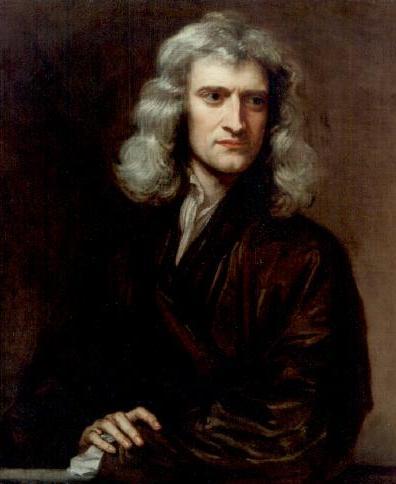

Isaac Newton (1642-1727) is considered by many, if not most, historians of science as the most important physicist and mathematician of all time. His work in the calculus, optics, motion, and gravitation set the stage for much of the science that has occurred since then. Almost all of his theories and discoveries represented huge departures from previous scientific thought.

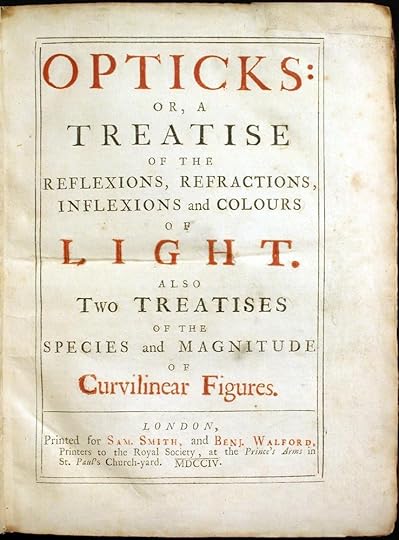

Newton did not write extensive scientific documents about atoms or the structure of matter. Instead, thoughts about these topics are scattered in his other publications. He leaves no doubt that he believes that matter consists of particles which are in motion through a vacuum, which he called pores. He also concludes that the pores can be the largest part of the volume of a substance. For example, based on the transparency of water he writes in Opticks (first edition, 1704), “Water has above forty times more pores than parts.”

Newton did not write extensive scientific documents about atoms or the structure of matter. Instead, thoughts about these topics are scattered in his other publications. He leaves no doubt that he believes that matter consists of particles which are in motion through a vacuum, which he called pores. He also concludes that the pores can be the largest part of the volume of a substance. For example, based on the transparency of water he writes in Opticks (first edition, 1704), “Water has above forty times more pores than parts.”

By the second edition of Opticks, he had established a hierarchical structure for matter. Particles had empty spaces between them. But each of the particles were in turn made of smaller particles and these smaller objects had empty spaces between them “till you come to solid Particles, such as have no Pores or Empty Spaces within them.”

A great contribution to our understanding of matter was Newton’s model of how matter was held together. From the Greeks through contemporaries of Newton, atoms needed to be in contact to stick together. Different types of atoms had different mechanisms such as hooks and loops to cause cohesion. (Makes you wonder why they did not invent Velcro.) From his study of gravity, Newton understood that forces could act at a distance. He applied this idea to the smallest particle of matter.

1689 Portrait by Godfrey Kneller

In his 31st Query in Opticks (second edition), Newton discusses this force and shows some of the reason that Niels Bohr said that Newton anticipated many things to come. For example, when speculating about the nature of the force, he describes, “[the attractions] which reach to so small distances as hitherto escape Observation; and perhaps electrical Attraction may reach to such small distances, when without being excited by Friction.” (In Newton’s time, electrical charges were separated and electrical phenomena studied by rubbing, much the way you get an electrical shock by shuffling across a carpet and touching a piece of metal. Thus, Newton was anticipating that electrical forces in nature could be created in other ways.)

Another look forward, also in the 31st Query, combined his hierarchical model with the attraction between particles:

“The smallest Particles of Matter may cohere by the strongest Attractions and compose bigger particles of weaker Virtue; and many of these may cohere and compose bigger Particles, whose Virtues is still weaker and so on for divers Successions, until the Progression end in the biggest Particles on which the Operations in Chymistry, and the Colours of natural Bodies depend, and which by cohering compose Bodies of a sensible Magnitude.”

Today, when thinking about the structure of matter, we consider quarks, protons, neutrons and electrons, atoms and molecules. Interactions such as the strong force and the electromagnetic force with vastly different strengths and ranges are involved in holding the various forms of matter together. Thus, Newton was on the right track about 300 years ahead of the rest of us.

As we have discussed in previous posts, religion played an important factor in discussions about atoms and the structure of matter. Newton weighed in on this aspect as well. In the Principia Mathematica, Newton discussed the ideas concerning God that had been attributed to the ancient Greeks such as Democritus and Epicurus: “They are thus compelled to fall back into all the impieties of the most despicable sects, of those who are stupid enough to believe that everything happens by chance, and not through a supremely intelligent Providence; of these men who imagine that matter has always necessarily exited everywhere, that it is infinite and eternal.” Rather strong words for those who did not see a role for God in the creation and development of the universe.

Replica of Newton’s second reflecting telescope of 1672 (© Andrew Dunn, November 5, 2004)

Light and optics were major subjects of Newton’s investigations. He learned that white light was composed of the colors, investigated the properties of lenses and prisms, and built the first telescope that used mirrors. To explain these observations, he developed a theory of light, which was built on light being small particles. That theory explained his observations but did not stand up after interference of light was discovered. In the early 19th century, a wave model of light was proposed and evidentially became the dominant model. (Things became more complex in the 20th century with the discovery of quantum effects. More on that later.) However, overall Newton’s ideas about the nature of matter provided important steps forward in humankind’s understanding.

In addition to his significant contributions to physics and mathematics, Newton conducted experiments in alchemy during most of his life. He did not publish about his alchemy but wrote extensively about his experiments in private documents.

Many of these writings remained in a collection that was not looked at by historians until the 20th century. These rather recent studies have revealed some of the influence of alchemy on Newton’s thoughts about the structure of matter. Next time, we will look at this aspect as well as the more general impact of alchemy and alchemists on theories for atoms.

Images via Wikimedia Commons, public domain unless otherwise noted

Previously:

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received four major awards — the American Association of Physics Teachers’ Oersted Medal (2014), the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and AAPT’s Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

November 29, 2013

Interpreting the First Thanksgiving

The First Thanksgiving, by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, circa 1912 to 1915 (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

It’s a lovely image, isn’t it? Two disparate peoples coming together to celebrate the harvest. The painting is full of inaccuracies in both the costume and manner of Native Americans and the English settlers. The Pilgrims didn’t wear black, and the Wampanoag did not wear elaborate feather headdresses and would not have been sitting on the ground. Also the Wampanoag should outnumber the settlers almost two to one.

Yet art is not about historical accuracy. In this case, the artist is trying to convey the ideals of peace and fellowship. So, join me at English Historical Fiction Authors for more of what the first Thanksgiving really might have been like.

Source: “Let’s talk turkey: 5 myths about the Thanksgiving holiday,” Wicked Local Cape Cod

November 22, 2013

A Surprising Fact about Thanksgiving’s Main Dish

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service photo

The tables of the first Thanksgiving might have been graced with a bird like the one pictured above. The English settlers bagged some kind of fowl for the feast, and the area is part of the wild turkey’s range.

Surprisingly, the first domesticated turkey came from farther south, much farther south. Details of its introduction to Europe are hazy, but apparently, this bird so closely associated in American minds with the quintessential American holiday was domesticated in today’s Mexico, Central America, and perhaps the American Southwest.

In the early 1500s, Spanish explorers took turkeys across the Atlantic. In Europe, the birds were popular, and by the middle of the century – decades before the Pilgrims – they were appearing in banquets in France, Italy, and England.

Centuries later, descendents of those birds will be the star banquets all across America as we celebrate Thanksgiving.

Source: foodtimeline.org

November 13, 2013

Three Plants Used for Evil

When Unusual Historicals put out the call for contributors to write about plants and their properties, I embraced the theme. After all, I enjoy gardening, so much that my south picture window has every inch crammed with greenery in the winter.

I was overwhelmed with choice. In the days before air fresheners, medieval people used strewing herbs such as thyme and mint to make their homes smell nice. Common dyes for clothes came from plants. And of course their diets depended on grains, fruits, and vegetables along with flavoring from the herb garden.

So what do I chose to write about? Hemlock, nightshade, and aconite – three poisons that appear in my forthcoming book, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar. If you share my morbid curiosity, visit Unusual Historicals and learn more.

The Death of Socrates by Giambettino Cignaroli (1706–1770)

November 7, 2013

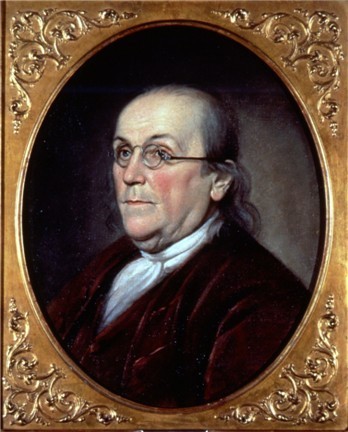

Benjamin Franklin’s Double Spectacles

Getting my first pair of bifocals (no line, of course) got me to thinking: was that story about Benjamin Franklin inventing them true? After all, some other tales I heard in grade school – like George Washington and the cherry tree – proved to be the product of someone’s imagination.

Portrait of Benjamin Franklin by Charles Willson Peale, 1785, via Wikimedia Commons

Well, bifocals really were the brainchild of Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), who improved upon the original medieval invention (created centuries after my novels take place).

Franklin might have been wearing glasses as a young man in the 1730s. Whether he avoided reading glasses like many of us who approach middle age is unknown; however, he found himself with two sets of spectacles, one for distance and one for reading.

Perhaps in the 1760s, he got tired of alternating pairs and had an optician cut the lenses in half and insert those semicircles into a single frame, readers on the bottom, distance vision on top. Not always an easy process. A 1779 letter from an optician says that he broke three pairs of glasses to produce one set of bifocals. And they were expensive then, too.

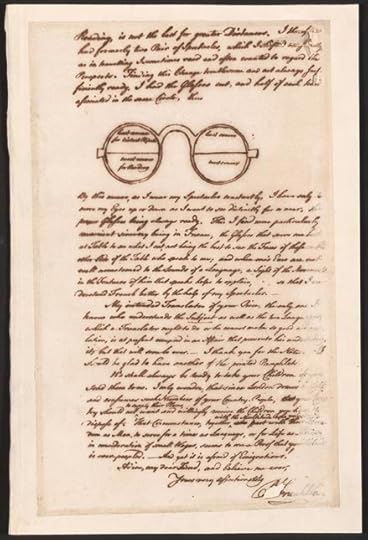

1785 letter from Benjamin Franklin to George Whatley, Library of Congress image

Franklin was pleased with his double spectacles as he wrote in a letter to a friend in 1785. Along with eliminating the annoyance of changing glasses, he was better able to see his food at the French dinner table and see the faces of people speaking to him in French, thus allowing him to use visual cues to more easily comprehend the language.

Interestingly, the term bifocal came decades after Franklin’s death, when John Isaac Hawkins coined the term in 1824, two years before inventing trifocals.

Source

“Benjamin Franklin-Father of the Bifocal,” Antique Spectacles and Other Vision Aids

November 1, 2013

Separating Atoms from Atheism

It’s the first Friday of the month – time for another blog post about the history of atom theory from physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman. Here we’re in the 17th century, and two movements start to disassociate atoms from atheism. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

By the middle of the 17th century, the atheism associated with atoms was a major barrier for those interested in moving the ideas forward. Fortunately, some natural philosophers were willing to address this issue directly. During the same time period, the change from natural philosophy as mostly thinking about the world to empirical science was creating a different environment in which ideas could be tested. We will look at a little of each of these movements in this post.

By the middle of the 17th century, the atheism associated with atoms was a major barrier for those interested in moving the ideas forward. Fortunately, some natural philosophers were willing to address this issue directly. During the same time period, the change from natural philosophy as mostly thinking about the world to empirical science was creating a different environment in which ideas could be tested. We will look at a little of each of these movements in this post.

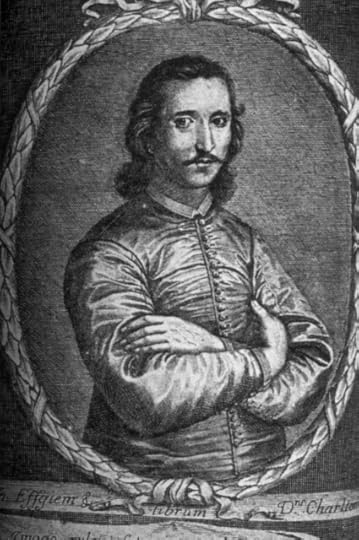

Walter Charleton

Walter Charleton (1619-1707) concluded that atoms could not have just happened but because of their complexity must have been the work of a God. He studied Gassendi’s work carefully and in 1654 wrote a book, Physiologia Epicuro-Gassendo-Charltoniana: a Fabrick of Science Natural upon the Hypothesis of Atoms, Founded by Epicurus, Repaired by Peturs Gassendus, Augmented by Walter Charleton. With a title like that, the treatise certainly must have attracted some attention. Charleton’s basic thesis was that God caused atoms to exist and set them in motion. These fundamental objects do not intrinsically have properties such color, sound, heat, cold, etc. Instead these properties are a result of the motion and shape of the atoms.

Thus, Charleton removed “the poisonous part of Epicurus’ opinion” (his words). It seems like a rather simple solution and is quite similar to the argument that creationists make today against evolution. But it seemed to have an effect on the thinking of the day. It also helped that Charleton wrote in English rather than Latin. Thus, his thoughts had a much broader circulation among English speakers who then as today were frequently weak in foreign languages – modern and ancient.

At the time of Charleton’s and others’ efforts, the stage was also set for a significant change in the way science was done. Francis Bacon (1561-1626) had described a scientific method not unlike the one we think about today. However, the person who put these ideas into practice was Robert Boyle (1627-1691), commonly considered the father of chemistry. Boyle is most remembered by students today as the person who stated the relation between pressure and volume in a gas – as one goes up the other goes down. Thus, his name appears in high school and college chemistry and physics books.

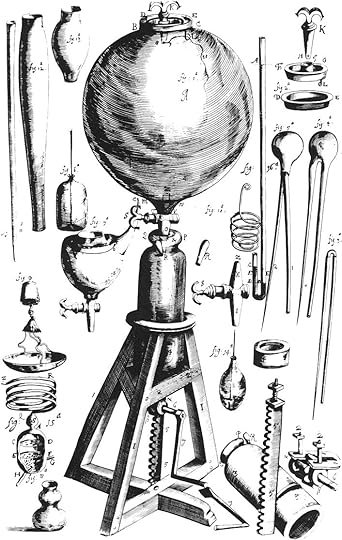

Boyle’s drawing of the air pump, 1661

However, Boyle’s Law about gases is only a small part of his accomplishments. Most importantly, he focused his work on experiments and observations. One of his assistants, Robert Hooke (1635-1703), designed an air pump which enabled them to remove air from an enclosure. (Hooke also has a law named for him, but it’s related to springs and is a different story.) As they conducted experiments in which they pumped out air, they were able to create a rudimentary vacuum. They discovered that in this vacuum sound does not travel, a candle cannot burn, and birds cannot live. Remember that the existence or nonexistence of a vacuum was critical to the opponents of atoms from Aristotle to Descartes. Now that one had actually been created, the momentum was on the atomists’ side.

In 1661, Boyle published The Sceptical Chymist, in which he argued strongly against the four elements of Aristotle. He did accept some of the views of Descartes such as particles can move more freely in liquids than in solids. However, he differed from Descartes on the fundamental idea of a vacuum. Descartes concluded that matter was continuous and thus the vacuum did not exist. Boyle had created one – almost.

Portrait of Robert Boyle by Johann Kerseboom, circa 1689

Boyle did seem to hedge his bets a little. In much of his work he used terms such a corpuscles instead of using the word atoms. Further, he discussed the elements of which “all bodies are … made and into which all these can ultimately be decomposed.” He was clear that the ancient Greeks’ fire, water, earth and air were not these elements. But he was less clear about what the elements were.

Boyle was an excellent person to enter the discussion while the conflict over atheism and the fundamental building blocks of matter was still going on. At age 11 or 12, Boyle was sent on a six-year educational tour of continental Europe. (His father, the earl of Cork, was one of the wealthiest men in Great Britain.) During this trip the young Boyle witnessed a very impressive thunderstorm. Apparently, the storm caused Boyle to have strong religious convictions that stayed with him the rest of his life.

In fact early in his career (1659), he wrote Some Motives and Incentives to the Love of God. Thus, his religious beliefs were well known, and yet he conducted experiments that strongly implied that atoms were the primary building blocks of matter. Today, of course, we do not see these two as necessarily being in opposition, but as we have seen during the past few posts, the view was different from the 17th century.

When I started these posts a year ago, I had expected to be close to modern times by now. However, I keep finding interesting (at least interesting to me) characters to investigate. Next time, we will move forward in time. We are getting close to one of the real giants – Isaac Newton.

Public domains images via Wikimedia Commons

Previously:

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

Did Gifted Scientist’s Belief in Atoms Led to His Obscurity?

Does Atom Theory Apply to the Earthly and the Divine?

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received four major awards — the American Association of Physics Teachers’ Oersted Medal (2014), the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and AAPT’s Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

October 23, 2013

Which Route Did Charlemagne Take to Invade Saxony?

I’ve spent a lot of time trying to decide on one word – west or south.

The current draft of my second novel, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, has the Saxons of Eresburg taken by surprise by an invasion from the west in 772. It was 14 years after their last battle with the Franks, who inhabit territory to the west and south. Yet an author of a recently published nonfiction book has the invasion coming from the south, and it is plausible.

No one knows the exact route Frankish King Charles (Charlemagne) would have taken. Those selfish Frankish annalists did not consider 21st century novelists when they wrote down their version of history, and the Continental Saxons did not even have a written language as we know it.

The extant annals pretty much say Charles held an assembly in Worms, invaded Eresburg, and destroyed the Irminsul, taking its silver and gold. He parleyed with the Saxons at the Wesser River and got 12 hostages, the medieval form of insurance for the vanquished to keep their promise to stay vanquished (and it often didn’t work).

So many questions are left unanswered. How many troops? How did they feed the soldiers plus horses and oxen transporting humans and supplies? And where did Charles cross the Rhine – a river that might remind Americans of the Mississippi – at a time when only a few bridges existed?

Sometimes the annalists throw us a crumb. In this case, it’s letting us know that in other years, Charles crossed the Rhine at Cologne and Lippeham, both sites with bridges. A Roman road from the bridge at Cologne would take them most of the way to Eresburg. However, this road would go through Saxony, past Syburg (a fortress mentioned three years after the first battle at Eresburg) and Paderborn, a settlement at that time.

A 14th century depiction of a war between Charlemagne and the Saxons, from Chroniques de France (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

I have no doubt Charles would have invaded with overwhelming force, even though it made a lot of noise and raised a lot of dust. He played to win. His army would make short work of a settlement like Paderborn and “forage” for food and supplies. And Syburg? That’s more complicated. If a fortress stood on that site in 772, it would have been an obstacle – one worthy of mention if conquered. It is not mentioned in 772 but is in 775, along with Eresburg being reconquered.

In Charlemagne’s Early Campaigns (768-777): A Diplomatic and Military Analysis, Bernard S. Bachrach speculates that Charles chose a different route, using waterways through Frankish lands east of the Rhine to transport heavy equipment like battering rams. He could have rested the animals and gotten supplies at the monasteries of Fulda and Fritzlar, then proceeded north to invade Eresburg.

When it comes to writing fiction, though, the story must be told through a character’s eyes. Leova, the heroine of Ashes, is a peasant woman who lives with her family near the fortress. She wouldn’t know about the invaders’ specific route, only the direction from which they are coming.

So what’s a historical novelist to do? In this case, leave this part of the manuscript as it is. I have the Franks going home on the road mentioned earlier. (The annalists are even less helpful when comes to route back to Francia. After Eresburg, they write, Charles spent Christmas in Herstal.)

My characters’ experiences on that road – such as a 12-year-old boy in a big, foreign city for the first time – are too good to pass up. And I don’t want to bog down the story by explaining how the Franks could come from the south but take a different direction to return to their country. But maybe I will add a sentence or two in the historical note explaining this uncertainty. In other words, why sometimes a novelist must make stuff up.

October 15, 2013

Religion and Magic: Two Ways Medieval Franks Manipulated Their World

A mix of religion and belief in magic was widespread in the days of Charlemagne, so an author of fiction set in that period has no choice but to give those beliefs a prominent role.

That’s why Alda, the heroine of The Cross and the Dragon, wears an amulet alongside the symbol of her faith. Leova, the heroine of The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, chants spells of protection, even after her conversion to Christianity.

The Church officially opposed magic and even imposed harsh penalties for sorcery, but it could not stop people from turning to magic – even among the clergy.

Visit Unusual Historicals for more about the role of religion and magic in Carolingian Francia.

A ninth century piece of jewelry called the Talisman of Charlemagne (from Wikimedia Commons, GNU Free Documentation License)

October 10, 2013

Hostages: An Early Medieval Form of Insurance

Hostage is one of those words that can cause confusion to people new to historical fiction set in the early Middle Ages. After capturing the Saxon fortress of Eresburg and destroying the Irminsul in 772, Charlemagne took 12 hostages, an event recounted in my forthcoming second novel, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar.

Today we think of a hostage as someone held against their will to extort money or some other demand, but the word’s meaning was slightly different for Charles and his contemporaries. To them, hostages were a means of making sure an enemy kept a commitment they made.

The vanquished took an oath of loyalty to the Frankish king, but swearing to a saint was not enough to reassure the monarch – or anyone else with sense. The vanquished party also surrendered hostages, often the young sons of important men.

As long as the vanquished behaved themselves and kept their oaths, the hostages would be treated as the king’s guests. If the vanquished broke their promises, the king could do whatever he wanted to the boys, whether that was sending them off to a monastery to be unwillingly tonsured, selling them into slavery, or killing them.

So with the lives of their offspring at stake, one would think the vanquished foes would be motivated to keep their promises. But hostage-taking often didn’t work in practice. When Charles was otherwise occupied – for example a war with his ex-father-in-law in Lombardy in 773 – the Saxons would move to retake lost territory. To the Franks, they were breaking a sacred oath. The Saxons, who never wrote down their story, might argue an oath at the point of a sword was invalid.

A sad part of the history remains untold – what happened to the hostages.

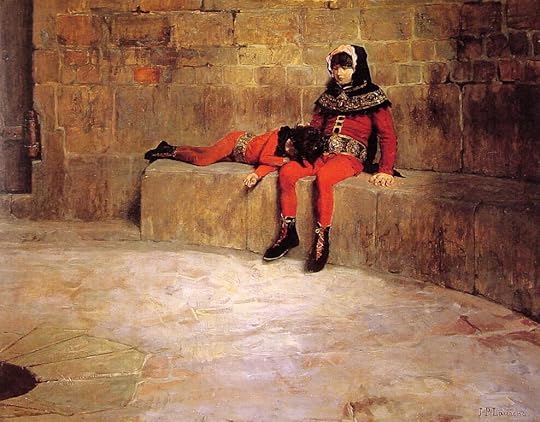

Hostages, Jean-Paul Laurens, 1896 (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)