Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 31

June 7, 2013

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

It’s the first Friday of the month, time for another post on the history of atom theory by physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman. In this installment, we’re in the 17th century, and a French clergyman seeks to reconcile the scientific theory of ancient Roman philosophers with Catholic teachings. Today is also the last day of the Summer Banquet blog hop, which includes my contribution, Dandelions for Dinner. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

In his book The Atom in the History of Human Thought, Bernard Pullman separates the 17th century development of ideas about atoms by religion. He notes that Catholics, primarily in France and Italy, wanted control over new ideas while Protestants, primarily in England, were somewhat indifferent toward thoughts about atoms. I will follow Pullman’s line of thought and spend a couple of posts looking at some Catholic 17th century views first.

In his book The Atom in the History of Human Thought, Bernard Pullman separates the 17th century development of ideas about atoms by religion. He notes that Catholics, primarily in France and Italy, wanted control over new ideas while Protestants, primarily in England, were somewhat indifferent toward thoughts about atoms. I will follow Pullman’s line of thought and spend a couple of posts looking at some Catholic 17th century views first.

As I discussed in the previous post, the concepts of atoms as expressed by Democritus, Epicurus, and Lucretius were available, primarily through copies of ancient manuscripts. However, these ideas were mostly rejected in favor of the philosophy and science of Aristotle. Recall that Aristotle’s physics could not include a void and thus he rejected the ideas of atoms. Further, Aristotle’s philosophy had become integrated into Catholic philosophy by this time.

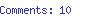

Pierre Gassendi (1592-1655), a French clergyman, set out to change this state of affairs. He wanted to bring together medieval religion, humanism as expressed in the Renaissance, and the science of his day. To do this, he set a goal of making Epicurean thought as acceptable as that of Aristotle.

1750 engraving by Michel Odieuvre (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

Gassendi’s writing on philosophy and science are extensive, so I will only touch on a few points here. Foremost, he sought, whenever possible, empirical evidence for his scientific ideas. For example, Galileo has concluded logically that a ball dropped from the mast of a moving ship would fall so that it landed on the ship next to the mast. Gassendi actually had the experiment conducted. Logic alone was not sufficient for him. When it came to atoms, he needed to rely on indirect evidence because direct observation was not possible. As we will see in the next paragraph, he sometimes needed to fudge a little on this point.

Gassendi’s atomism was extensive. To bring these ideas into acceptability for the Church, an important part was allowing God and atoms to both have a place in his worldview. The ancient Greeks stated that atoms were eternal. Creation was not part of their system. Gassendi rejected this idea even though he would be hard pressed for empirical evidence. In his worldview atoms were created by God. Even more, God provided atoms with their motions. Thus, God preordained what would happen because future events would be determined by the motions and collisions of these atoms.

Another issue was the soul. The ancients had concluded that souls as well as bodies were made of atoms. Gassendi’s view was maybe that’s OK for cats and broccoli but not for humans. Human souls had a spiritual component which was created by God.

With topics such as Creation and souls covered, Gassendi could build an atomism that used the ancient Greek’s ideas as a foundation. His atoms were real objects not mathematical points. They were in constant motion in all directions. They had a variety of properties and even combined to form molecules. Overall, Gassendi allowed atoms to be acceptable and not inconsistent with the faith of his day. In Pullman’s words, “From a historical perspective, it could be said that Gassendi added God to atoms, although he probably would have preferred to be seen as having returned atoms to God.” And, atoms were returned to the scientific thought of the 17th century.

Gassendi was almost 30 years younger than Galileo. Of course, Galileo had his own problems with the Church. One (and as far as I can determine only one) historian believes that these problems involved atoms as well as the solar system. We will look at that issue next time.

Previously:

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received three major awards—the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and American Association of Physics Teachers’ Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

June 2, 2013

Dandelions for Dinner

Part of the challenge with participating in a blog hop with a food theme is that there are no surviving menus from Carolingian era (eighth and ninth century Europe), the time period for my novels. Not exactly a surprise when you consider that few people, including cooks, could write.

Part of the challenge with participating in a blog hop with a food theme is that there are no surviving menus from Carolingian era (eighth and ninth century Europe), the time period for my novels. Not exactly a surprise when you consider that few people, including cooks, could write.

But we can make some pretty good guesses. Dandelions, for example, are an Old World plant, introduced to the States by the Puritans. It is not too much of a stretch to imagine these hardy, easy-to-grow perennials with a long season in medieval peasants’ gardens or simply harvested from the meadows near their homes.

Yours truly serving up a side dish.

Peasants did not eat meat every day, and the summer would be a good time to let animals grow and get as big as possible. However, if they were having a good spring, they would have had plenty of vegetables, including chickpeas, and as anyone who’s ever weeded a flower bed know, dandelions were reliable. Add a little barley, and you have a meal.

So, an inventive medieval peasant woman might have created something like the following recipe, transforming tough, bitter greens into something tasty.

Note: I gathered the dandelion greens from my backyard, where we use no pesticides, herbicides, or chemical fertilizers. Nor do we have dogs. I would have spent much less time cleaning the greens if I had harvested the dandelions when the leaves were dry and the trees were not exploding with pollen.

Dandelions and Chickpeas over Barley

1 gallon bag full of dandelion greens (This may seem like an awful lot but they will shrink.)

3 tablespoons salt per 8 quarts of water

2-3 spring onions

1 cup pearled barley (Closest to I can get to what medieval folk might have had in the small Indiana where I live.)

1 1/2 tablespoons of butter

1 can of chick peas (OK, Anachronism Police, I know full well canned food did not exist during the Middle Ages. But chickpeas were in Charlemagne’s gardens. They could be used fresh or dried for later. I’m also cheating by using an electric stove instead of a cook fire, and I’m not about to give up my dishwasher. So there.)

Set about 8 quarts of water on the stove to boil.

Start the barley and prepare according to package directions.

Clean the dandelions thoroughly.

Chopped the greens into 2-inch pieces. You should have about 10 cups. (Really, they will shrink.)

Chop the onions.

When the water is boiling, add salt.

Add greens. Cook until ribs are tender, about 10 minutes. (Don’t worry if the greens are still bitter at this stage. They will be tasty when sautéed.)

Drain the greens and pour cold water over them.

Squeeze out excess moisture. (Told you they would shrink.)

Melt 1 tablespoon butter in a skillet.

Add onions. Cook a few minutes until softened.

Add the greens and sauté until butter is absorbed. This takes only a few minutes.

Add chickpeas and cook until heated through. This takes only a few minutes.

Add remaining butter, and it’s ready to serve.

Thanks for visiting this stop on the blog hop. I invite you to check out the authors below for their thoughts on food. All of us are offering giveaways.

[image error]My prize is an e-book of my first novel, The Cross and the Dragon, a tale of love amid the wars and blood feuds of Charlemagne’s reign. To enter, leave a comment in this space only, with your e-mail address so the winner can be contacted. To get an extra entry, mention that you’d like to get an e-mail (just one, I promise) announcing the publication of my second book, tentatively titled The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar. The contest closes Friday, June 7. A winner will be selected at random and be announced in an update to this post.

Hop Participants

Random Bits of Fascination (Maria Grace)

Pillings Writing Corner (David Pilling)

Anna Belfrage

Debra Brown

Lauren Gilbert

Gillian Bagwell

Julie K. Rose

Donna Russo Morin

Regina Jeffers

Shauna Roberts

Tinney S. Heath

Grace Elliot

Diane Scott Lewis

Ginger Myrick

Helen Hollick

Heather Domin

Margaret Skea

Yves Fey

JL Oakley

Shannon Winslow

Evangeline Holland

Cora Lee

Laura Purcell

P. O. Dixon

E.M. Powell

Sharon Lathan

Sally Smith O’Rourke

Allison Bruning

Violet Bedford

Sue Millard

Kim Rendfeld

June 1, 2013

An Interview with Alda of Drachenhaus

A character interview is an interesting and fun exercise for a writer, and you can see the results on today’s post at Laurie’s Thoughts and Reviews, where the heroine of The Cross and the Dragon shares her thoughts. On the eve of the Frankish invasion of Hispania, I was somehow able to communicate with Alda of Drachenhaus, despite the language barrier. (Alda lives in the eighth century Francia, before modern English was created.)

So if you’d like to know why Alda prefers Hruodland to Ganelon, why the amulet she gives her husband is charmed, and why King Charles is invading Hispania, check out Laurie’s Thoughts and Reviews.

May 28, 2013

Queen Mother Gerberga: Protecting Her Sons – and Her Power

When brother-in-law King Charles seized her late husband’s lands, Gerberga decided to fight for her sons’ inheritance and her own power as queen mother and regent.

After Frankish King Carloman died at age 20 in December 771, Charles moved swiftly to seize the kingdom. Was it determination or desperation that made Gerberga flee with an entourage to Lombardy? Was it her idea or did her late husband’s magnates persuade her?

We don’t know how she reached the realm of Charles’s ex-father-in-law. She would have either had to cross the Alps or go by sea. The slow travel in general posed the danger of brigands, but add winter weather and at least one boy too young to ride, and this journey becomes especially risky.

[image error]

A cropped image from the 1882 Costumes of All Nations depicting Frankish costume (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

We don’t know much about Gerberga, except that she was a Frankish noblewoman selected by father-in-law Pepin to marry Carloman, but we can make a few guesses. Women typically were teenagers when they married and could be as young as 13. Men could marry at age 16. The most Gerberga and Carloman could have been married was four years, and their elder son was no more than 3 years old, barely old enough to start riding.

That this queen mother, perhaps as young as 17, made a dangerous journey to Lombardy with these two little boys tells us something about her character.

Seeking aid from Desiderius, the king of Lombardy, was not the safest thing to do, either, but she had no other choice. Desiderius had clashed violently with Rome before, and his retaliation was brutal and typically medieval (for more about him, see my guest post on Tinney Heath’s Historical Fiction Research blog). However, he was the powerful ally she needed – and one who was furious with Charles over the Frankish monarch’s repudiation of his daughter.

Desiderius saw her sons as a way to get back at Charles for the insult to his daughter and restore his alliance with Francia. He tried to get the pope to anoint her sons as kings, even seizing papal lands to pressure him. The pope refused and eventually asked for Charles to fulfill his vow as protector of Rome and come to his aid.

When Charles invaded in 773, Desiderius fled to Pavia, and Gerberga and her sons went to Verona, along with Lombard Prince Adelchis and a Frankish nobleman named Autchar. Adelchis escaped Verona and headed toward the Byzantine empire.

Charles, learning of Adelchis’s flight, went to Verona with a contingent of Franks, while most of the army held siege in Pavia. Gerberga surrendered voluntarily when Charles arrived.

The sources don’t say why she surrendered. Perhaps she realized she was deserted, knew there was no way she could win, and wished to avoid further bloodshed or the starvation and disease that accompanies a siege. Perhaps, she thought if she surrendered now, she and her sons would be sent to the cloister rather than executed.

The sources are silent about her fate, but having Gerberga and her sons in the cloister is plausible. They would have been among other troublesome relatives Charles sent to the monastery such as Desiderius and later on Charles’s first cousin Bavarian Duke Tassilo and even his eldest son, Pepin (often called Pepin the Hunchback – medieval folk were a tad insensitive).

Gerberga did not win her battle against her brother-in-law, whom we today called Charles the Great, or Charlemagne, but her story illustrates that medieval women were not damsels in distress waiting for a hero to rescue them.

Sources

Charlemagne: Translated Sources, P.D. King

Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories, translated by Bernhard Walters Scholz with Barbara Rogers

“Pavia and Rome: The Lombard Monarchy and the Papacy in the Eighth Century,” Jan T. Hallenbeck, published in 1982 by Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

The Life of Charlemagne, Einhard, translated by Evelyn Scherabon Firchow and Edwin H. Zeydel

You also might like

Bertrada: Queen Mother and Diplomat

The Role of Carolingian Queens

A Mystery: Why Did the King Want to Divorce the Queen?

Charlemagne’s High Stakes Family Feud

The Last Lombard King

May 21, 2013

Bertrada: Queen Mother and Diplomat

In the early months of 772, Bertrada was the queen mother of Francia, one of the most influential political positions, yet I doubt anyone would envy her situation. Her younger son, King Carloman, had died on December 4 at age 20, and her elder son, King Charles, quickly seized his late brother’s realm, denying her grandsons their inheritance.

On top of that, Charles divorced a Lombard princess, the wife that Bertrada had picked out for him, and married Hildegard, the daughter of an important count in his brother’s kingdom.

In medieval Francia, there is more a stake than a mom embarrassed by her son’s scandalous behavior. In royal circles, marriages were a means of building alliances. Charles’s marriage to Hildegard solidified his hold on Carloman’s lands, but his divorce endangered Francia’s relationship with Lombard.

Bertha Broadfoot, 1848, by Eugène Oudiné at Luxembourg Garden, Paris. (copyrighted photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons).

For a little context, let’s rewind four years. On his deathbed in 768, King Pepin divided his lands between sons Charles and Carloman, following Frankish custom. Charles’s kingdom formed a crescent around Carloman’s. Charles was 20 and Carloman, 17, and both likely were already married to brides their father had chosen.

The brothers did not get along, and tensions increased when Carloman refused to help his brother quash a 769 rebellion in Aquitaine. Enter Queen Mother Bertrada, who had taken the widow’s veil. Bertrada might have wanted to prevent a civil war and preserve the kingdom her husband had built.

It’s unclear whether Lombard King Desiderius or Bertrada thought up a union or two between their children, but she agreed to a marriage between Charles and one of Desiderius’s daughters, even if that meant setting aside Charles’s then wife, Himiltrude, and offending a noble Frankish family. A marriage between Charles and a Lombard meant Charles would have access to Italy without passing through his brother’s realm and therefore less reason to attack his brother.

The spring and summer of 770 was a mix of slow, dangerous travel and diplomacy for Bertrada. She spoke first to Carloman then traveled through Bavaria, the duchy held by the kings’ first cousin (also Desiderius’s son-in-law), and crossed the Alps, traversing steep slopes on horseback. In Rome, she reassured the pope, who had written a strongly worded letter against the idea, that this arrangement would be beneficial, then went to Lombardy and returned to Francia with the princess.

After Charles second marriage, Bertrada’s importance at court is evident. In his letters, the pope addresses her first.

The arrangement strengthened Charles’s relationship with Lombard and Rome, but apparently, one of Carloman’s legates, Dodo, didn’t think it was good for his lord. Whether Carloman agreed with Dodo is unclear – the pope gives the king the benefits of the doubt. Nevertheless, in the spring of 771, the pope’s minister turned on him, with warriors led by Dodo. Desiderius came to the pope’s rescue and used that opportunity to take a brutal revenge on the minister.

Sometime that year, Carloman became ill and died several months later. That’s when Bertrada saw all her handiwork fall apart.

In writing The Cross and the Dragon and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, I had to grapple with what it would have been like for Bertrada in the aftermath of Carloman’s death. One element that affects my portrayal of her comes from Einhard’s biography of Charlemagne, in which he says the monarch treated his mother with respect and had her in his household. Their only disagreement was the Lombard princess, whom he had married to please her.

I decided she would support her son, but she would be angry, especially as the Franks go to war with Desiderius in the fall of 773.

Bertrada’s widowed daughter-in-law was not about to let her toddling sons lose their kingdom without a fight. That daughter-in-law, Gerberga, is the subject of next week’s post.

Sources

Charlemagne: Translated Sources, P.D. King

Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories, translated by Bernhard Walters Scholz with Barbara Rogers

“Pavia and Rome: The Lombard Monarchy and the Papacy in the Eighth Century,” Jan T. Hallenbeck, published in 1982 by Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

The Life of Charlemagne, Einhard, translated by Evelyn Scherabon Firchow and Edwin H. Zeydel

You also might like:

The Role of Carolingian Queens

A Mystery: Why Did the King Want to Divorce the Queen?

Charlemagne’s High Stakes Family Feud

The Last Lombard King

May 17, 2013

My Playlist? A Writing Quirk? Read the Interview.

Today, I am visiting with Star at the Bibliophilic Book Blog for a fun interview. Among Star’s thoughtful questions are:

How did writing this book affect you?

Do you have a musical playlist you listen to while writing? If so, what kind of music?

What would you say is your most interesting writing quirk?

Find out the answers at the Bibliophic Book Blog.

[image error]The Cross and the Dragon also made a recent appearance at Enchanted by Josephine. In her review, Lucy Bertoldi says, “I really appreciated the author’s in- depth knowledge of the history and her knack to create from it a novel busting with impeccable details that carried me vividly into medieval times. A wonderful debut for Kim Rendfeld!”

May 14, 2013

Above All, We Must Protect the Saint’s Relics

778, Fulda – As pagan Saxon warriors closed in, the monks fled for their lives. With them was their most precious possession, the bones of the martyred Boniface.

They feared that their enemy would slaughter everyone and burn their monastery. They spent a night at a daughter house and then three days in tents before learning it was safe to return. Men in the area had rallied beaten back the Saxons.

Saint Boniface Crypt, Fulda Cathedral, Germany (image released to public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

What made Boniface so important that the monks risked their safety to protect his remains? Boniface had supervised the monastery’s founding, but the monks didn’t protect his body only for sentiment. At that time, Boniface might have been canonized – he is “of saintly memory” when the Royal Frankish Annals were written in the 790s – and his bones were now relics, attributed with supernatural power.

Yet that brings up another question: What kind of a life did Boniface lead to make him worthy of sainthood? For that, see my debut post on one of my favorite blogs, English Historical Fiction Authors.

May 7, 2013

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Here is the latest installment on the history of atom theory by physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman, and we are now at the cusp of the Renaissance, where political intrigue has left an unemployed former Vatican official searching for a good book to copy and sell to wealthy patrons. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

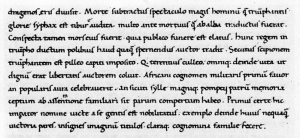

In the previous post I mentioned that some of the classical Greek works were preserved by “passing through” the Middle East. Because of strong scholarship in the Middle East while Europe was in the Dark Ages, these documents were translated into Arabic and later back into Latin. Some of the classical Greek and Roman intellectual works took another route. They lay dormant for centuries, usually in monastery libraries. Then, they were discovered by individuals who made an effort to find these materials. Roman poet Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things (De Rerum Natura), which includes description of atoms, was one such document.

In the previous post I mentioned that some of the classical Greek works were preserved by “passing through” the Middle East. Because of strong scholarship in the Middle East while Europe was in the Dark Ages, these documents were translated into Arabic and later back into Latin. Some of the classical Greek and Roman intellectual works took another route. They lay dormant for centuries, usually in monastery libraries. Then, they were discovered by individuals who made an effort to find these materials. Roman poet Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things (De Rerum Natura), which includes description of atoms, was one such document.

Prior to the middle of the 15th century, documents were reproduced by individuals making one copy at a time. Much of this copying was done by monks, presumably because with no worldly temptations they had a lot of time available. Thus, only a limited number of any written work would be available. The number of documents was also limited by the lifetime and availability of the material on which books were written.

Parchment and papyrus could last only a few hundred years. Further, they were relatively rare, so sometimes a copyist would scrape ink off one manuscript because he or she wanted to reuse the parchment. If these were not sufficient destructions, insects and worms saw books as lunch. With all of this, it is amazing that any of the Greek and Roman manuscripts survived at all.

Poggio as depicted by Alfred Gudeman in the 1911 book Imagines Philogorum.

But they did. By the end of the 14th century book hunters were looking through libraries attempting to find classical works of philosophy and science. In the next few paragraphs I will briefly tell the story of Poggio Bracciolini, the man who rediscovered and disseminated Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things. (Books have been written about Poggio, so this is description is very incomplete.)

Poggio’s family had rather modest means. So, when he entered adulthood and wished to move into the professional world, he needed something to get him started. That something was his handwriting. Because everything was copied by hand, a person with outstanding skills at writing was a valuable resource, one that could earn good money in Florence at the end of the 14th century. Poggio used his talents and the money he earned from them to become trained as a notary. Thus, he came to know influential and wealthy Florentines such as Niccolo Niccoli who had a strong interest in all things Greek and Roman and who will play a role later in this story.

A sample of Poggio’s handwriting.

In 1403, Poggio decided to move to Rome where he joined the staff of the pope. The Vatican at this time was not a pleasant work environment. Poggio wrote a collection of stories that reflect some of what he heard about the activities of the pope’s staff in a book called Facetiae. Because this blog is family-friendly, I cannot include any of the stories here. In spite of the atmosphere in Rome, Poggio flourished and eventually rose to the rank of apostolic secretary, essentially the pope’s personal secretary.

In 1410, Poggio’s new boss, Baldassare Cossa, was elected pope and took the name John XXIII. However, others also claimed to be the pope. In 1414 a meeting was convened in Constance, Germany, to resolve the conflicting claims to the papacy. The end result was that John XXIII was disposed and imprisoned. His name was stricken from the official register of popes so that more than five centuries later another man, Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, could again choose the name John XXIII.

De rerum natura copied by Girolamo di Matteo de Tauris for Pope Sixtus IV, Italy, 1483.

Poggio, thus, found himself in Germany and unemployed. So, he began searching the monasteries in the area for ancient books. In January 1417, Poggio entered a monastic library. He did not record its location, but historians think that it was in Fulda, Germany. There, he found a copy of Lucretius’s poem. Apparently, he was not allowed to remove the manuscript from the library.

Instead, he hired someone to make a copy for him. Poggio sent that copy to his longtime friend Niccolo Niccoli in Florence. Niccoli had copies made and kept them. For a long time he did not return any version to Poggio. After 12 years, he finally sent a copy to Poggio and made copies available to others. Lucretius’ explanation of atoms and the philosophy of Epicurus were once again in circulation.

Over 50 copies from the 15th century still exist, so a large number must have been made. Shortly thereafter Gutenberg entered the scene and many more (printed) copies went into circulation.

How important this discovery and dissemination was to the development of ideas about matter is not completely clear. In his award-winning book The Swerve: How the World Became Modern Stephen Greenblatt makes a case for Poggio’s discovery being the real beginning of the Renaissance. Others have, however, disputed this claim. (See for example, “Why Stephen Greenblatt is Wrong — and Why It Matters” by Jim Hinch or “The Swerve by Stephen Greenblatt: A flawed but dazzling study of the origins of the Renaissance” by Colin Burrow.) Independent of how important Poggio’s work was to the intellectual development of Europe, without people such as he who meticulously scoured through libraries and copied old manuscripts, we would not likely have access today to many of the works of ancient thinkers.

With the Renaissance comes a more “modern” view of the scientific methods. Eventually those methods lead to a slow steady development of our ideas of atoms. In the next post we will start that story.

(All images are in the public domain via Wikiamedia Commons.)

Previously:

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received three major awards—the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and American Association of Physics Teachers’ Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

May 2, 2013

The Challenge of a Medieval Man as a Hero

It’s the first Friday of the month, and usually a guest post by physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman highlights the history of atom theory. Today through Monday, this space will be dedicated to the Heroes and Villains blog hop. Enjoy the post about the hero of The Cross and the Dragon below and check out the giveaway and other bloggers. Then come back to Outtakes on Tuesday for another installment on the history of how we came to understand atoms.

Any portrayal of Roland, whom I call Hruodland in The Cross and the Dragon, is going to be fictitious. The only thing we know about the historical eighth-century governor of the March of Brittany is where and when he died.

Any portrayal of Roland, whom I call Hruodland in The Cross and the Dragon, is going to be fictitious. The only thing we know about the historical eighth-century governor of the March of Brittany is where and when he died.

The Hruodland of The Cross and the Dragon is a product of my imagination, as Roland is a product of the imaginations of the people who created The Song of Roland, Orlando Inamorato, Orlando Furioso, and the legend behind the origin of Rolandsbogen.

Roland at Roncesvalles, Odilon Redon, c.1869 (public domain image via Wikipaintings)

So do I make him the hero who bravely faces overwhelming odds at the Pass of Roncevaux and stubbornly refused to call for aid? Do I make him the bridegroom grieving over the separation from his beloved?

Those questions pale compared to the greatest challenge for anyone writing historical fiction set in the Middle Ages: a hero who is true to his times yet whom modern readers will like and root for.

Unless their protagonist is an antihero, all fiction writers must balance making a character virtuous enough to be sympathetic but flawed enough to be realistic. Medieval times present other obstacles such as:

Medieval folk likely favored harsh justice for criminals, such as putting out an eye, slitting nostrils, or letting bandits, often accused of murder and rape, strangle slowly on the hangman’s noose.

Carolingian Franks were intolerant of pagan religions.

Wife-beating was a right.

Men thought women enjoyed sex and wondered if their wives would restrain themselves when they were away. A man knew whose blood his sister had, which is why his relationship with nephews and nieces was special; he had to take his wife’s word that her children were his.

Given all that, what kind of hero did I create? Hruodland has a common medieval attitude toward women and therefore doesn’t completely trust his wife, so he is prone to fits of jealousy. But he values her intelligence, compassion, and cleverness. He will stop at nothing to get her back when they are separated, and he is willing to pay any price to protect her.

This post about Hruodland and my process for creating him is part of the Heroes and Villains blog hop, May 3-6, in which almost 30 authors of fantasy, science fiction, and historical fiction discuss our heroes or our villains. And we all have giveaways.

[image error]Mine is an e-book of The Cross and the Dragon. To enter, leave a comment in this space only, with an e-mail address so that I can contact the winner. If you’d like to get an extra entry, thus increasing your odds, mention that you would like to receive an e-mail (note the singular) announcing the publication of my second book, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, which features am eighth-century Continental Saxon peasant who will do anything to protect her children.

The winner will be chosen at random and announced in an update to this post after the hop. In the meantime, please check out the posts and the giveaways of the authors below.

Nyki Blatchley

Martin Bolton

Debra Brown

Adrian Chamberlin

Mike Cooley

Karin Cox

Rhiannon Douglas

Joanna Fay

Peter B Forster

Ron Fritsch

Mai Griffin

Joanne Hall

Jolea M Harrison

Tinney Sue Heath

Eleni Konstanine

K. Scott Lewis

Paula Lofting

Liz Long

Peter Lukes

Mark McClelland

M. Edward McNally

Sue Millard

Ginger Myrick

David Pilling

EM Powell

Kim Rendfeld

Terry L Smith

Tara West

Keith Yatsuhashi

April 29, 2013

The High Stakes of Etiquette for Young Ladies in the Regency

Today, it is my pleasure to welcome author Maria Grace back to Outtakes. You might remember Grace from a post she did about laundry in the Regency, which made me all the more grateful for my front loader. Grace is visiting Outtakes as she promotes her most recent title, All the Appearance of Goodness, the third book in her Given Good Principles series. In her post about Regency etiquette, Grace shows us a lot more than good manners is at stake. – Kim

By Maria Grace

During the Regency era, a young lady’s social standing depended on her reputation, which could be marred by something as simple as an immodest fall while exiting a carriage. So, to preserve her chances of making a good marriage – which for most was the making or breaking of their future life – the utmost care to all aspects of etiquette was required.

During the Regency era, a young lady’s social standing depended on her reputation, which could be marred by something as simple as an immodest fall while exiting a carriage. So, to preserve her chances of making a good marriage – which for most was the making or breaking of their future life – the utmost care to all aspects of etiquette was required.

To complicate matters further, well-bred women were thought to have a “natural” sense of delicacy. Taste and poise, it was believed, should come naturally to a lady. It was an indictment against their breeding to be worried about looking correct. The significance of these matters could not be underestimated, for once a young woman’s reputation was tarnished, nothing could bring it back. Her future could be forever dictated by a single unfortunate incident.

Thus, although these patterns of etiquette might appear awkward and restrictive, especially for women, they safeguarded against misunderstanding and embarrassment.

Ladylike Deportment

On the Threshold (of a Proposal) by Edmund Blair Leighton, 1900

Ladies were encouraged to maintain an erect posture when sitting or standing. Slouching or leaning back was regarded as slothful unless one was infirm in some way. A well-bred young woman walked upright and moved with grace and ease. She maintained an elegance of manners and deportment and could respond to any social situation with calm assurance and no awkwardness.

Proper ladies behaved with courteous dignity at all times to acquaintance and stranger alike. They kept at arm’s length any who presumed too great a familiarity. Icy politeness was their weapon of choice to put so-called “vulgar mushrooms” in their place. Extremes of emotion and public outbursts, even including laughter, were unacceptable, as was anything pretentious or flamboyant. A woman, though, could have the vapors, faint, or suffer from hysteria if confronted by vulgarity or an unpleasant scene.

Chaperones

Young women were protected zealously in company since to be thought “fast” was the worst possible social stigma. Young, unmarried women were never alone in the company of a gentleman, save family and close family friends. A chaperone was also required for a young single woman to attend any social occasion. Under no circumstances could a lady call upon a gentleman alone unless consulting him on a professional or business matter, and she never forced herself upon a man’s notice.

Except for a walk to church or a park in the early morning, a lady could not walk alone. She always needed to be accompanied by another lady, an appropriate man, or a servant. Though a lady was permitted to drive her own carriage, if she left the family estate, she required the attendance of a groom. Similarly, on horseback she should bring an appropriate companion to protect her reputation.

Introductions

Man Bowing to a Woman by Alfred Grèvin (1827-1892)

The need for formal introductions was another means by which women’s reputations were protected. Until a formal acquaintance was recognized, individuals could not interact. Once the man of the house performed introductions for the women in his household, they could socialize with their new acquaintances.

Once introduced, it was essential for a lady to politely acknowledge that person with a slight bow of the shoulders anytime she encountered them in public. If she did not make such an acknowledgement, a gentleman did not acknowledge her. Failure to recognize an acquaintance was a breach in conduct and considered a cut. Manuals warned that a lady should never “cut” someone unless “absolutely necessary.”

Conversation

The heart of polite sociability was conversation, and ladies were encouraged to develop the art of pleasing and polite exchange. Acceptable topics were highly limited; the list of unacceptable topics far outnumbered the acceptable ones.

One did not ask direct personal questions of new acquaintances. Remarks, even complimentary ones, on the details of another’s dress might also be regarded as impertinent. Personal remarks, however flattering, were not considered good manners and might be exchanged only with close family and intimate friends. Similarly, scandal and gossip were omitted from public conversation. Proper ladies were expected to be shocked at the mention of anything evil, sexual, compromising, or related to bodily functions. Ladies were even warned against blowing their nose in company for similar reasons.

Touch

Not surprisingly, all forms of touching between members of the opposite sex were to be kept to a minimum. A gentleman might put a lady’s shawl about her shoulders, or assist her to mount a horse or enter a carriage, or take her arm through his to support her while out walking. Shaking hands, though, was considered less proper. A pressure of the hands was the only external signs a woman could give of harboring a particular regard for certain gentleman and was not to be thrown away lightly.

Dancing

Hush! by James Tissot, circa 1875

In a society governed by such strict rules regulating the interaction of the sexes, the dance floor provided only of the only places potential marriage partners could meet and courtships might blossom. The ballroom guaranteed respectability and proper conduct for all parties since they were carefully regulated and chaperoned. Under cover of the music and in the guise of the dance, young people could talk and even touch in ways not permitted elsewhere.

At a public ball, the master of ceremonies would introduce gentlemen and ladies to enable them to dance, as a lady could not dance with a gentleman to whom she had not been introduced. At a private ball, though, all guests were assumed to be introduced and a lady could dance freely.

A young woman did not dance more than two pairs of dances with the same man or her reputation would be at risk. Even two dances signaled to observers that the gentleman in question had a particular interest in her. The day after a ball, a gentleman would typically call upon his principle partner, so a young lady who danced two sets with same gentleman might rightfully expect continued acquaintance with him.

At the Dining Table

A private ball also meant a dinner service. Depending on the hostess, the ladies might proceed to the dining room together, parading in rank order, or might be escorted in on the arm of a gentleman whose rank matched their own.

Within the dining room, guests were not assigned seats. The hostess sat at the head of the table with the ranking male guest at her right. The host took the foot of the table with the ranking female guest at his right. Other guests were free to select their own seats as they chose, though there was a tacit understanding that seats closest to the hostess should be taken by the highest ranking guests.

Each gentleman would serve himself and his neighbors from the dishes within his reach. If a dish was required from another part of the table, a manservant would be sent to fetch it. It was not good form to ask a neighbor to pass a dish. It was equally bad manners for the ladies to help themselves. Gentlemen also poured wine for the ladies near them.

Eating quickly or very slowly at meals was considered vulgar as was a lady eating or drinking too much. She must not eat her soup with her nose in the bowl nor bring food to her mouth with her knife – a fork or spoon was the proper implement for the job. Her napkin belonged in her lap, not tucked into her collar as the gentlemen did. She must not scratch any part of her body, spit, lean elbows on the table, sit too far from the table, pick her teeth before the dishes are removed, or leave the table before grace is said.

The so many strictures, it is no wonder etiquette manuals abounded in the era and even less wonder that they were diligently studied by young ladies and their mothers alike.

References

A Lady of Distinction - Regency Etiquette, the Mirror of Graces (1811). R.L. Shep Publications (1997)

Black, Maggie & Le Faye, Deirdre - The Jane Austen Cookbook. Chicago Review Press (1995)

Byrne, Paula - Contrib. to Jane Austen in Context. Cambridge University Press (2005)

Day, Malcom - Voices from the World of Jane Austen. David & Charles (2006)

Downing, Sarah Jane - Fashion in the Time of Jane Austen. Shire Publications (2010)

Jones, Hazel - Jane Austen & Marriage. Continuum Books (2009)

Lane, Maggie - Jane Austen’s World. Carlton Books (2005)

Lane, Maggie - Jane Austen and Food. Hambledon (1995)

Laudermilk, Sharon & Hamlin, Teresa L. - The Regency Companion. Garland Publishing (1989)

Le Faye, Deirdre - Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels. Harry N. Abrams (2002)

Ray, Joan Klingel - Jane Austen for Dummies. Wiley Publishing Inc. (2006)

Ross, Josephine - Jane Austen’s Guide to Good Manners. Bloomsbury USA (2006)

Selwyn, David - Jane Austen & Leisure. The Hambledon Press (1999)

Trusler, John - The Honours of the Table or Rules for Behavior During Meals. Literary-Press (1791)

Vickery, Amanda - The Gentleman’s Daughter. Yale University Press (1998)

All images are in the public domain and from Wikimedia Commons, with the exception of the author photo and book cover image.

About Maria Grace

Though Maria Grace has been writing fiction since she was 10 years old, those early efforts happily reside in a file drawer and are unlikely to see the light of day again, for which many are grateful. She has one husband, two graduate degrees and two black belts, three sons, four undergraduate majors, five nieces, six cats, seven Regency-era fiction projects and notes for eight more writing projects in progress. To round out the list, she cooks for nine in order to accommodate the growing boys and usually makes 10 meals at a time so she only cooks twice a month. She is also a contributor to English Historical Fiction Authors and Austen Authors.

Though Maria Grace has been writing fiction since she was 10 years old, those early efforts happily reside in a file drawer and are unlikely to see the light of day again, for which many are grateful. She has one husband, two graduate degrees and two black belts, three sons, four undergraduate majors, five nieces, six cats, seven Regency-era fiction projects and notes for eight more writing projects in progress. To round out the list, she cooks for nine in order to accommodate the growing boys and usually makes 10 meals at a time so she only cooks twice a month. She is also a contributor to English Historical Fiction Authors and Austen Authors.

She can be contacted at:

E-mail: author (dot) MariaGrace (at) gmail (dot) com

Facebook: facebook.com/AuthorMariaGrace

Amazon.com: amazon.com/author/mariagrace

Her website, Random Bits of Fascination: AuthorMariaGrace.com

Twitter: @WriteMariaGrace

Pinterest: pinterest.com/mariagrace423/