Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 35

December 12, 2012

Florentines’ Claim to Charlemagne

Again, please welcome Tinney Sue Heath, author of A Thing Done, as she discusses the impact the legend of Charlemagne had on medieval Florentine identity.—Kim

By Tinney Sue Heath

Tinney Sue Heath

The Florentines believed Charlemagne had re-founded their city in 801 after its destruction by Attila (actually by Totila the Goth, in 410). Nor did they forget that “when the Lombard fang bit holy Church, under its wings Charles the Great came victorious to her aid,” referring to Charlemagne’s victory over the Lombard King Desiderius in 773. These words are spoken by the soul of the Emperor Justinian in the Heaven of Mercury (Dante’s Paradiso 6.94-96, all translations in this post by Robert Durling).

The Medici seal (photo by Tim Heath)

Several of the great Florentine families prided themselves on their supposed descent from one of Charlemagne’s knights. The Medici, for example, held that their ancestor, the brave knight Averardo, had done battle with a ferocious giant and slain him. They claimed that the circles on their coat of arms represented dents in Averardo’s shield from the blows dealt by the giant’s mace.

Also, the Adimari clan claimed that their progenitor Adimaro was one of Charlemagne’s knights. Dante did not think highly of this family; he called them “the presumptuous clan that is like a dragon against those who flee, but is placated like a lamb by those who show their teeth or their purse” (Paradiso 16.115-117).

Detail of a fresco depicting Florence about the mid-1300s (this public domain image and the one of Dante via Wikimedia Commons).

Some scholars (though not by any means a majority) believe that Charlemagne figures once more in the Divine Comedy. In Dante’s cryptic and much-debated prophecy in Purgatorio 33.43, where he poses a riddle involving the number 515, they think he might be referring to the year 1315, which is to say, 515 years after the coronation of Charlemagne in A.D. 800. We are not, however, aware of anything particularly cataclysmic by Dante’s standards that occurred in 1315.

Yet it was the sudden death in 1313 of a successor to Charlemagne, Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII, that dealt the exiled Dante the blow that destroyed any hope he had of ever returning to his native Florence. Gradually, over the years of his exile, Dante the former Guelf had come to believe that this young and relatively untried emperor could stand up to stubborn Florence and restore him, its unjustly exiled citizen, to his rightful place. He began to see the empire as the necessary corrective to what he saw as the injustices and evils perpetrated by his city.

Dante

Dante was among the many who paid homage to Henry after his coronation in Milan, and he urged the emperor, in letters that still exist, to march on Florence and even to attack her. The empire that Charlemagne had created was to have been Dante’s salvation, and his disappointment was bitter indeed when his hopes unraveled.

Perhaps when Dante wrote in his Divine Comedy about watching Charlemagne and Roland as if following the falcon in its flight, he was thinking of the eagle that symbolized the empire and of what might have been.

Tinney Sue Heath is the author of A Thing Done, which is about a jester who gets caught up in a prank that leads to a vendetta among the ruling families in Florence. For more about Tinney and her work, visit her website, tinneyheath.com, or her blog, Historical Fiction Research.

Previously: Dante’s vision of Charlemagne and Roland in the afterlife.

The lasting power of legends related to Roland.

Tomorrow: Let’s go to the (blog) hop

December 11, 2012

Dante’s Vision of Charlemagne in the Afterlife

Today, I am glad to welcome Tinney Sue Heath, author of A Thing Done, published recently by Fireship Press. Here, she discusses how Dante interpreted the legend of Roland, more than four centuries after the attack at the Pass of Roncevaux.—Kim

By Tinney Sue Heath

Tinney Sue Heath

“Thus for Charlemagne and Roland my attentive gaze followed them both, as one’s eye follows his falcon in its flight.” So Dante in his Divine Comedy describes his vision of the two French heroes in the Heaven of Mars (Paradiso 18.43-45; my translation, all others in this post by Robert Durling).

Dante

By this point in the Comedy, Dante has already worked his way downward through the depths of the Inferno, where he sees the soul of Ganelon, the betrayer of Charlemagne and Roland, then up again through the Purgatorio, and having traded his pagan guide Virgil for the heaven-dwelling soul of his beloved Beatrice, is now progressing through the Paradiso itself.

Heroes in Paradise

The king and his knight (Carlo Magno and Orlando, to Dante) are in august company. The soul of Dante’s ancestor, the knight Cacciaguida, has directed Dante’s gaze toward the arms of the Cross, where the poet will gaze on the blessed souls of great heroes.

Two, Joshua and Judas Maccabaeus, are Old Testament figures. The others were defenders of Christendom in their lifetimes and have thus earned their exalted position in Paradise: Charlemagne and Roland share that honor with their contemporaries William, count of Orange and the giant Rainouart (Dante believed the giant was a historical figure and that he was converted to Christianity by William); with Duke Godfrey of Boulogne, leader of the first Crusade; and with Robert Guiscard, the Norman commander who fought against the Muslims to establish the Norman kingdom of Sicily.

[image error]

A 14th century manuscript depicts the Chanson de Roland.

An earlier reference to Roland occurs in the Inferno, when Dante hears “the sound of a horn so loud that it would make any thunder feeble… After the dolorous rout, where Charlemagne lost the holy company, Roland did not sound his horn so terribly.” (Inferno 31.11-13, 16-18.)

Dante and his fellow Italians of the 13th century were very familiar with the characters of La Chanson de Roland. The story in brief, as Dante knew it, was this: Roland, Charlemagne’s nephew and a great paladin, was leading the king’s rear guard when they met with an ambush in the pass of Roncesvalles, due to the perfidy of the treacherous Ganelon, Roland’s stepfather and Charlemagne’s brother-in-law. Roland delayed too long in blowing his ivory horn to alert Charlemagne to what was happening, and the company was slaughtered. When Ganelon’s betrayal came to light, he was punished by being pulled apart by four horses.

The Villain’s Fate

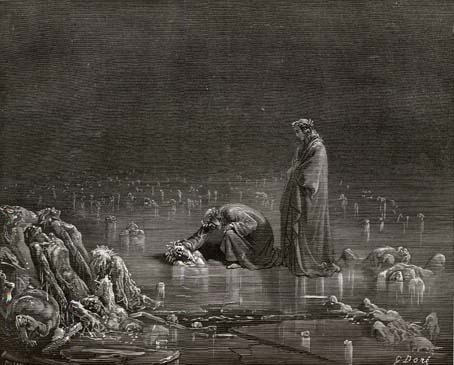

But what of Ganelon, considered (with Judas) the archetypal traitor by Dante and his contemporaries? It will come as no surprise that he is to be found in the frozen lowest part of hell (at the point where it really has frozen over), encased in ice, only a short distance from where Satan is eternally gnawing on the greatest traitors of all: Brutus, Cassius, and Judas.

A 19th century illustration of the Inferno by Gustave Dure

It is in Antenora, the second zone of Cocytus (the ninth circle of Hell) that we find the political traitors. Dante, a member of the Guelf faction, has a harsh and violent encounter with one of these, Bocca degli Abati, who in Dante’s eyes was the traitor who cost the Florentine Guelfs the battle of Montaperti and caused the River Arbia to run red with blood. Bocca, of a Ghibelline family, feigned Guelf sympathies and pretended to fight with the Guelfs, but at a decisive moment in the battle, he cut off the hand of the Guelf standard-bearer, plunging the Guelf army into fatal confusion.

It is Bocca who points out Ganelon to Dante. The Florentine and French traitors and other notorious betrayers dwell forever “down there where the sinners keep cool” (Inferno 32.116-117). The Italian, “là dove i peccatori stanno freschi,” as Ronald Martinez points out, includes the expression “star fresco,” which means “to be cool” but also “to be in for it.” It may have been a saying known to Dante, but whether he quoted it or coined it, the phrase is still in use today.

Tinney Sue Heath is the author of A Thing Done, which is about a jester who gets caught up in a prank that leads to a vendetta among the ruling families in Florence. For more about Tinney and her work, visit her website, tinneyheath.com, or her blog, Historical Fiction Research.

Next: Medieval Florence’s claim to Charlemagne’s legend.

Previously: The lasting power of legends related to Roland.

You might also like: What really happened at the Pass of Roncevaux.

Public domain images from Wikimedia Commons. Tinney’s author photo by W. Clinton Hotaling.

December 10, 2012

Centuries Later, the Legend of Roland Endures

Regular readers of Outtakes will notice that I emphasize the eighth-century history of Charlemagne and Roland rather than the legend. Or to be more accurate, legends that have spanned centuries and countries.

The only historical account of Roland, called Hruodland in my novel The Cross and the Dragon, is in part of a sentence in Einhard’s ninth-century biography of Charlemagne in which he details the 778 ambush at the Pass of Roncevaux by the Christian Basques. In reality, the battle was a disaster for the Franks, so traumatic that apparently no one wrote about it while King Charles was alive. (See my post in Unusual Historicals for accounts about the actual events.)

I will talk more about the real world of The Cross and the Dragon in person at 2:30 p.m. Saturday, December 15, at the New Castle-Henry County Public Library in New Castle, Indiana. Today, I will touch on a handful of the fictional accounts.

Hruodland most often goes by Roland and Orlando in legend. The best known is the 11th century anonymous Old French epic, The Song of Roland. Here, he is the stubborn hero facing overwhelming odds in his fight against the Muslim Saracens.

The legend spreads even further. The German story that inspired The Cross and the Dragon (spoiler alert) has the character building a castle on the Rhine just to get a glimpse of the bride who thought he was dead and committed herself to a convent on a nearby Rhineland island (end spoiler).

In the late 13th century, the story has travelled north and become part of the Norse Karlamagnus saga, in which Roland and Oliver kill the Saxon Vitakind (a variant of the historic Saxon leader Widukind, and like the other legends, it’s very different from actual events).

In the 15th and 16th centuries, Italian poets take the legend into the fantastic with Orlando Innamorato and Orlando Furioso. And legend still lives on in marionettes.

“Even today, the main subject matter in the famous puppet shows of Sicily is the story of Carlo Magno, Orlando, and the other French knights,” says Tinney Sue Heath, author of A Thing Done. “These tales are presented in episodes, one short part of the story at a time, at puppet theatres throughout Sicily and the southern mainland – rather like watching episodes of Flash Gordon’s adventures each week in movie theatres in the 1930s. The puppet characters and their noisy sword battles continue to entertain audiences of locals and tourists alike.”

Tomorrow and Wednesday, Tinney will discuss how the legends of Roland and Charlemagne affected 13th century Florence, the setting of her novel, and its most famous poet, Dante.

Sicilian marionettes depict one of the Roland legends (photo by Tim Heath).

December 7, 2012

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

It’s the first Friday of the month, and that means another installment in the series about the theory of atoms from physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman.–Kim

By Dean Zollman

What happens internally when a plant or animal grows? How do we smell an aroma almost as soon as someone walks into a room with flowers? Where does the “stuff” go when a plant decays? These questions may have occurred to earlier civilizations, but the Greeks were the first to record answers them.

What happens internally when a plant or animal grows? How do we smell an aroma almost as soon as someone walks into a room with flowers? Where does the “stuff” go when a plant decays? These questions may have occurred to earlier civilizations, but the Greeks were the first to record answers them.

We cannot see what is happening in these and many other situations, so we must build a scientific model in any attempt to understand it. Greek philosophers in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE had many ideas about substance and how thing change. However, Leucippus and Democritus were the first to develop a model that is similar, in some ways, to our present ideas of atoms.

They concluded that all matter was made of small indivisible and indestructible objects. These objects were called atoms, based on the Greek word atomos, or indivisible. Leucippus and Democritus hypothesized that atoms came in a variety of sizes and shapes. The atoms combined in different ways to form the difference that we see.

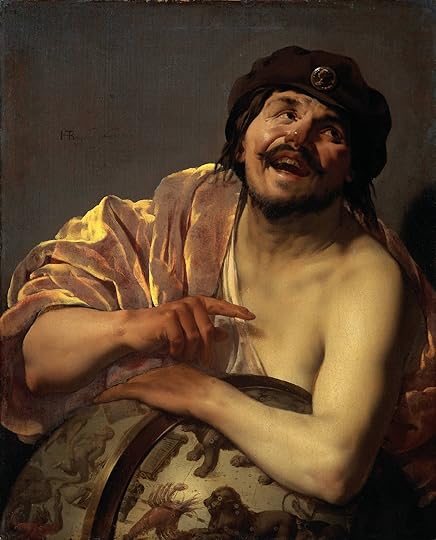

Democritus, as depicted in 1628 by Hendrick ter Brugghen (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

Democritus, who is sometimes called the laughing philosopher, developed the concept further and stated that these atoms were in constant motion, frequently colliding with each other. With this kind of motion, he could explain the aroma from flowers. The atoms from the flowers move across the room colliding with air atoms and spreading out through the room along the way. When the reach our nose, we smell the roses.

For atoms to move through the room Democritus needed to postulate that empty space existed. Atoms cannot move unless there is space to move in. This empty space was called the void.

Two very important philosophers of the generations that followed Democritus did not like these ideas. The void did not exist. Plato never mentions Democritus. Plato’s student, Aristotle, was somewhat more direct in his criticism.

Aristotle’s description of forces and motion required that all space be filled with matter. So, he felt the need to refute Democritus’s ideas. Aristotle wrote at length describing Democritus’ concepts about atoms and what was wrong with them.

We are fortunate that Aristotle did this. Most of Democritus’ writings have been lost. If Aristotle had not described Democritus’ ideas so he could tell the world why Democritus was wrong, we might not today know how close to right Democritus was.

On the other hand, Aristotle’s science and philosophy dominated Western thought for most of the next 2,000 years. So interest in Democritus’ atoms, except in a few cases, was limited for a long time. We will look at one of those cases, an epic poem by Lucretius, next time.

Previously: An overview of the history of the theory of atoms.

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University, where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received three major awards—the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and American Association of Physics Teachers’ Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

December 3, 2012

Contacting Reviewers: A Few Rules of Engagement

As a published author, I am very thankful for book bloggers. Not only have these unpaid reviewers given The Cross and the Dragon their endorsements, they have also exposed it to new audiences.

So far, The Cross and the Dragon has been the subject of 13 reviews and interviews on the blogosphere, and it’s not done yet. I will continue to reach out to reviewers in the months ahead.

In the hopes of being helpful to both authors and reviewers, I’d like to share a few tips for authors, especially those who published with a small press or self-published. Much of this comes from my experience as a journalist, when I was on the receiving end of a pitch for free publicity.

Rule No. 1: Be Nice

Remember that you are asking someone for a favor. You are asking them to spend hours with your book and write down what they think–for free.

Many reviewers are writing their blogs on their own time, while they maintain a full-time job, fulfill family obligations, have other responsibilities, or a combination of all of the above, just like you.

Rule No. 2: Read the Review Policy

Because of the time commitment bloggers make, it only stands to reason that they select books for review that they think they’ll like. So if a reviewer says they won’t read a novel in your genre, move on. It’s not personal.

Literary tastes are like food tastes. I happen to like Brussels sprouts, but some people won’t eat them, even through there is nothing wrong with the vegetable. Don’t waste the reviewer’s time and yours by offering something they said they don’t like, or worse clogging their inbox with the e-book or wasting your money by mailing an unsolicited print book.

Nor it is anything personal if a blogger can’t accept any new books until they catch up on their backlist.

Rule No. 3: Read the ‘About Me’ Section

I always like it when a letter is addressed to me personally rather than “Dear Author,” and I can only surmise reviewers would appreciate the same courtesy. If you find something that you have in common–such as being members of the Historical Novel Society, for example–it helps to make that connection.

Rule No. 4: Send Only a Pitch

I will not send unsolicited books, electronic or print, unless the review policy states otherwise.

Ebooks and images are large files, and clogging an inbox with unsolicited files is annoying. You’re not going to get a yes by annoying people.

As for print, well, I want to expend resources where they will do the most good. Having my unsolicited book land in someone’s mailbox only to be unread is a waste of money.

My experience at my last job at a daily newspaper in a midsize Indiana city colors this view. We were sent unsolicited books in the hopes they’d be reviewed. My newspaper didn’t publish reviews, even of local authors.

Rule No. 5: Have the Basics Covered

OK, the basics need to be done before you send your first e-mail. You need to have a strong, enticing blurb of 200 words or less. (An earlier post in Outtakes details how I wrote my blurb.)

You should have an excerpt and first chapter posted on your website so that you can link to them in your e-mail and help the blogger decide whether they want to devote time to your work.

Rule No. 6: Be Professional

The e-mail you send to a reviewer likely is their first impression of you. Bad spelling, bad grammar, and rambling writing is a turn off, just like it is with agents and editors.

Rule No. 7: Be Flexible

In this case, those of us who are published with a small press or self-published have an advantage. No one is putting pressure on us for our sales to do well within the first two weeks—or else. If it will be two months (or more) before a blogger can post the review, it still will make an impact.

And be patient (see rule No. 1). Constantly asking “are we there yet” doesn’t speed up the trip. I have followed up with bloggers when they’re running late on reviews, but I’ve waited a few weeks.

Rule No. 8: If You’re Offered an Alternative, Accept It

Endorsements are wonderful, especially when you’ve tried for years to be published and could paper a large walk-in closet with all your rejection letters. But it’s not always possible for a blogger to fit a review into their schedule. An interview or a guest post is still a free way to expose your work to a new audience.

Rule No. 9: Realize You Might Still Get No for an Answer or Not Get an Answer at All

Even if you follow all of my suggestions, I can’t guarantee you’ll get a review. I have lots unanswered e-mails. This is not a complaint, and I don’t take it personally. Some reviewers get so many e-mails, they simply can’t answer them all, and I must assume that my novel and these particular readers were just not meant for each other.

Rule No. 10: If You’re Tempted to Pay for a Review, Don’t

Paying for a review taints the whole process and ruins it for all authors and readers. The only trade should be a free book for an honest review.

A paid reviewer’s claim that they won’t guarantee a review will be favorable lacks credibility. A business needs satisfied customers to survive.

You are much better off enlisting the services of a virtual book tour organizer or making an investment of time, whether that is in making sure you’ve contacted the right reviewers or improving the book itself.

I welcome everyone’s comment but would especially appreciate feedback from reviewers. What advice would you give to authors seeking to have their work reviewed?

November 28, 2012

Anticipation and Anxiety: Medieval Childbirth

As my husband and I get ready to welcome our third grandchild in May, I am thankful the birth will happen in this century, with its hospitals, ultrasounds, good nutrition, sanitation, epidurals, and scientifically based prescriptions and medical care.

Childbirth in the Middle Ages was very different. Babies were born at home. In aristocratic houses, think low-ceilinged, dark, cozy rooms. Think midwives and female friends. Think white magic. And above all, absolutely no men.

Even today, childbirth is not without risk or complications, but it is a lot safer. In the Middle Ages, more than one-third of adult women died during their childbearing years. So an impending birth must have been greeted with a mix of anticipation and anxiety.

For more, see my post about medieval childbirth on Unusual Historicals.

This image by Masaccio appears on a 15th century desco da parto, a tray used to bring food to a new mother while she recovers from childbirth in her lying-in chamber. When not in use, the trays were wall decorations (public domain image from Wikimedia Commons).

November 20, 2012

Carrots: Medieval Medicine and Food

There was a fine, fuzzy line between vegetables and herbal remedies in the Middle Ages. The carrot is one example.

Public domain image from the Agricultural Research Service, an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, via Wikimedia Commons.

The World Carrot Museum, which I found through foodtimeline.org, has an incredibly detailed history of this common vegetable, today used in everything from savory dishes to desert.

In the Middle Ages, carrots appear in texts that describe their medicinal and culinary value. Illustrations show them with orange roots, a contrast to the white roots of their wild cousins or the purple and yellow roots of the plants the originated in today’s Afghanistan.

Early medieval texts don’t always distinguish between carrots and parsnip, but when they’re mentioned as food, they can be boiled or parboiled, then fried, and good when mixed with other dishes.

According to sources from the Middle Ages (for specifics see the medieval chapter of the carrot’s history), healers believed parts of carrots as a medicine can:

can regulate a woman’s menstrual cycle

aid conception

induce abortions (but not by ingestion)

assist those with painful urination

treat pleurisy and chronic coughs

treat bites from poisonous animals and spiders

heal sores when ground leaves are mixed with honey

be an ingredient to treat colic and dysentery as well as glaucoma

Charlemagne apparently thought carrots were important enough for the royal gardens. His 785 capitulary about imperial lands and imperial courts list them among 90 desirable vegetables, herbs, flowers, and fruit trees.

November 14, 2012

What if Long-Ago Letters Were Part of High School History Classes?

My favorite source when reconstructing the Carolingian era, the period for The Cross and the Dragon, is the letters that are with us today.

Too many of us learned history in high school as an exercise in memorization. Remember who did what on what date long enough to write it down on a test. Then you can promptly forget it.

Too often, our classes were deprived of the actual human beings who made history. People who celebrated victories, mourned their loved one, fell in love, got angry. And that is why I wonder what a history class would be like if students read letters from long ago, from all levels of society.

The letter writers have a definite point of view. They don’t know everything that is going on. Nor do they know how events are going to turn out. But that’s the point! Letters show what the writer was thinking at the time.

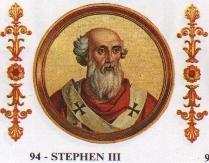

One example is a 770 missive from Pope Stephen III, responding to rumors that the daughter of his enemy, the Lombard king, will marry one of the Frankish kings. This is addressed to both Charles (today called Charlemagne) and Carloman. (Warning: Medieval people were not politically correct.)

Pope Stephen III, represented in an icon inside the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.

Stephen writes: “For what sort of madness—which is the very least it may be properly called—is this, most eminent sons, great kings, that your illustrious people of the Franks, which shines forth above all peoples, and the lineage of your royal power, of such splendor and high nobility, should be defiled—perish the thought!—by the perfidious and most foully stinking people of the Lombards, one in no wise reckoned within the number of peoples, a race from which a stock of lepers is known for certain to have sprung!”

What we see is a real human being, one who is very upset, trying to influence the events as they are happening. If high school students saw something like this, they’d be more interested in what happened in the past. The reason this is important is that knowing where we’ve come from guides us to where we’re going.

To anyone else who has researched history, what gems have you found in letters?

November 13, 2012

Interview with The Maiden’s Court about “The Cross and the Dragon”

[image error]Today, I am talking about The Cross and the Dragon, a tale of love amid the wars and blood feuds of Charlemagne’s reign, as well as my other works at The Maiden’s Court.

Its host, Heather, holds full-time job and is pursuing a master’s degree in history, with a concentration on the ancients and classics. Amazingly, she still make time to read and to blog.

Heather asks great questions, including:

Your novel, The Cross and the Dragon, is set during the time of Charlemagne, around the year 778-–this is not a typical choice of time or setting. What was it about this period that inspired you to set this novel, and your other works-in-progress, here? How did you come to be interested in Charlemagne?

This time period would be difficult to research, I would imagine. Is this true and where did you have to go to find your sources, and what kind of information do you have access to?

You previously worked as a journalist. What has it been like to shift to writing fiction? Have you always wanted to write a novel?

Find out the answers at The Maiden’s Court.

November 9, 2012

The Authors Corner at the Big Book Sale

Book lovers within driving distance of New Castle, Indiana, might want to check out the local library on Saturday, November 17.

From 9 a.m. to 2 p.m., you will have a chance to chat with an eclectic mix of five authors during the book and craft sale at the New Castle-Henry County Public Library, 376 South 15th Street. Amid the crafts and used books, the sale will have a new feature: an authors corner. And yours truly is one of the authors.

Allow me to make introductions:

The Cross and the Dragon: In this tale of love amid the wars and blood feuds of Charlemagne’s reign, Alda must content with a jilted suitor bent on revenge and the anxiety that her husband will be killed in the coming war. Published by Fireship Press.

I Always Do Laundry on Monday: This book of poetry and prose includes the title poem about the world of the author’s mother in the 1950s and 60s. Darlene describes it as “sentimental and silly, fun and faith filled.”

The Ambassador’s Daughter: Olivia Carvell is abducted by rebels and saved by a future king, only the beginning of a convoluted journey to true love. Published by Belfire Press.

The Ambassador’s Daughter: Olivia Carvell is abducted by rebels and saved by a future king, only the beginning of a convoluted journey to true love. Published by Belfire Press.

Tennessee Moonlight: Ann Mason fights to keep spoiled playboy Jackson Barrister from building a resort next door. He wants to learn what really happened the night her husband died. Published by Whiskey Creek Press.

If Ever That Time Come: Rowena Conrad is accidentally transported into the wilderness of Colonial America and meets the frontiersman she will marry.

The Gazebo: Rowena’s daughter, Abigail Russell, and Black Jack Bolton find love amidst the dangers and privations of the Revolutionary War.

The Gazebo: Rowena’s daughter, Abigail Russell, and Black Jack Bolton find love amidst the dangers and privations of the Revolutionary War.

Strangers and Pilgrims: Shannon DeHaven, a girl from Indiana, meets and marries David Ben Isaacs, an Israeli Mossad operative, and encounters undreamed of danger and intrigue.

Voni Ryan (pen name for Violet L Ryan and Toni Cantrell)

Absentminded: Nano imprint lithographer and ace police detective battle rogue government agents and greedy CEO for control of Nano Encoding Device with deadly potential. Published by Belfire Press.

Absentminded: Nano imprint lithographer and ace police detective battle rogue government agents and greedy CEO for control of Nano Encoding Device with deadly potential. Published by Belfire Press.

The Light Side of Dark: The writing team of Violet L Ryan and Toni Cantrell strikes again with this scary, funny, sometimes macabre short story collection. You’ll find everything from ghouls and ghosts to laughter and love. Published by Belfire Press

Allen Simmons-Cantrell (pen name of Toni Cantrell and Bea Simmons)

Like Him with Friends Possess’d: A contemporary love story set in southern Indiana. Published by Belfire Press

Like Him with Friends Possess’d: A contemporary love story set in southern Indiana. Published by Belfire Press

The book and craft sale is sponsored by the Friends of the Library, a volunteer-run organization that helps support programs, concerts, and other endeavors not covered by property taxes. Full disclosure: I am a member of the Friends board and am selling books through its gift shop.