Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 36

November 5, 2012

Great Way to Start November for ‘The Cross and the Dragon’

[image error]November 2012 is just a few days old, and The Cross and the Dragon has been busy making appearances, with three wonderful reviews.

Historical Novels Review, published by the Historical Novel Society,” calls The Cross and the Dragon “…a modern take on a Sir Walter Scott type of romance, and one that will work for a modern audience.”

HNS is devoted to the enjoyment of historical fiction. If you’re an author or a fan of this type of literature, I urge you to join. Full disclosure: I have been a proud member of HNS since 2003.

The Cross and the Dragon was featured at A Bookish Affair this past week. Meg says, “Alda was a really stand-out character for me. She is most definitely a woman before her time. She is strong. She is not afraid to go after what she wants…Bottom line: Good historical fiction with a strong lead character.”

Meg’s love of book goes way, way back to when she was a toddler pulling books from shelves and pretending to read. Her love of books today is apparent.

The third stop for The Cross and the Dragon last week was at A Bookish Libraria. Deborah Previte says, “Her main characters, Alda and Hruodland, are as engaging and inspiring as any Romeo and Juliet I’ve ever read about…It’s a solidly good book with an engaging story to tell. If you love historical fiction, you’ll be as enchanted as I was with this one.”

Deborah is a writer with degrees in fine arts, art history/museum studies and English lit. Her blog reflects her eclectic reading choices.

Many thanks to these reviewers for taking the time to read and review my debut novel.

November 2, 2012

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Today, I’m happy to host my father, Dean Zollman, for a monthly series of blog posts on the history of the theory of atoms. I asked my dad, a physics professor at Kansas State, to write history of science posts because he is a great storyteller and an excellent teacher. His posts will be published the first Friday of the month.—Kim

By Dean Zollman

In his Lectures on Physics, Richard Feynman asks his students rhetorically, “If all scientific knowledge were lost to a cataclysm, what single statement would preserve the most information for the next generation of creatures? How could we best pass on our understanding of the world?”

In his Lectures on Physics, Richard Feynman asks his students rhetorically, “If all scientific knowledge were lost to a cataclysm, what single statement would preserve the most information for the next generation of creatures? How could we best pass on our understanding of the world?”

He answers his questions with, “I believe it is the atomic hypothesis that all things are made of atoms—little particles move around in perpetual motion, attracting each other when they are a little distance apart, but repelling upon being squeezed into one another. In that one sentence, you will see, there is an enormous amount of information about the world, if just a little imagination and thinking are applied.”

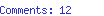

An early 20th century model of the atom. (Image from Wikimedia Commons, used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License)

These atoms which Feynman (and most of us) consider so important have not always existed in the universe. For about 380,000 years after the Big Bang (start of the universe, not the TV series) the amount of energy in the universe was too great for atoms to form. At that time, an electron was too energetic to be held to a proton and thus form a hydrogen atom.

But eventually the universe expanded and cooled enough that hydrogen and helium atoms were formed. Then later, stars and eventually the elements that we know today formed. The story of how all of this happened is an interesting one. Perhaps even more interesting are the ways in which we have been able to learn that it happened. (NASA has some good websites for that information.)

However, the stories of the Big Bang and our understanding of the evolution of the universe are not the stories that I wish to tell. An equally interesting tale is humankind’s views of atoms and how we came to understand them.

Much of this history is part of Western thought and began about 2,500 years ago in Greece. However, it is not exclusively Western (more about that in some future posts). And of course, there is the time period in which Alda and Hruodland lived (at least lived in the fictional world of The Cross and the Dragon). For an eighth and ninth century ruler, Hruodland’s uncle, Charlemagne, was relatively enlightened about intellectual endeavors. However, thinking about matter as being made of lots of objects too small to see did not sit well with early Christianity. (Again, more later.) So, Charlemagne’s “science advisors” were more likely to think about the stars than the constituents of matter.

A theory of atoms did not return to Western scientific thinking until the beginning of the 19th century. At that time John Dalton used the concept to explain experiments in chemistry. However, it was the discoveries of the late 19th and early 20th century that put atomic theory on firm ground. (We will get to those ideas later.)

In the next post, we will start at the beginning—not the beginning of atoms, but the beginnings of humankind’s understanding that they may exist. We will discuss briefly how Leucippus and Democritus concluded that something like atoms exists. Then, we will look at why Aristotle thought they were wrong even though without Aristotle we, today, would probably not know about Leucippus’ and Democritus’ ideas.

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received three major awards—the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and American Association of Physics Teachers’ Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

November 1, 2012

An Interview with Elizabeth Caulfield Felt about ‘The Cross and the Dragon’

Today, I am being interviewed by fellow historical novelist and Indiana University grad Elizabeth Caulfield Felt.

If Elizabeth’s name is familiar, it might be because she wrote a post on Outtakes about a fascinating woman, Adèle Hugo, best known as Victor Hugo’s crazy daughter. In her post and her novel Syncopation: A Memoir of Adèle Hugo, Elizabeth casts doubt on that notion.

Elizabeth Caulfield Felt

A former reference librarian, Elizabeth teaches a course on children’s literature at the University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point. She’s also the author The Stolen Goldin Violin, a mystery for younger readers, and is working on story that gives a different interpretation of Cinderella and her stepsisters.

Here is a sampling of the questions Elizabeth has for me:

The Cross and the Dragon derives some of its characters and much of its storyline from the French legend The Song of Roland. Can you tell us what drew you to that story and how you decided to make it your own?

How much historical fact is woven into your novels?

How do you think being a journalist has helped and/or hindered your career as a creative writer?

Darcy or Heathcliff?

Visit Elizabeth’s blog to find out the answers.

October 22, 2012

The Naming of Cats is Easy; Try Naming Characters

Ever experience what you think is a small job become something major like scraping off that bit of peeling paint to do a touch up only to find yourself repainting an entire room?

That’s how I’m feeling right now as I search for a new name for my heroine of my second novel, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar. Her current name is Acha, but that is too similar to Alda, the heroine of my first novel, The Cross and the Dragon.

To further complicate matters, my heroine is a pagan Continental Saxon, a society that didn’t have a written language as we know it at the time. So I turned to their cousins, the Anglo-Saxons.

While searching Google books, I came across and gem–or a trap, depending on how you label it: The Onomasticon Anglo-Saxonicum. Published in 1897, it is a huge list of Anglo-Saxon names before and after the Domesday Book, the latter commissioned by William the Conqueror to take inventory.

Widukind memorial in Herford, Germany, rebuilt from an 1899 sculpture by Heinrich Wefing. (By M. Kunz via Wikimedia Commons, used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.)

As I read about naming conventions, I was presented with a new issue. Family members had similar names, too similar for my taste. Kentish Earl Eormenred’s children were Eormenbeorh, Eormenburh, and Eormengyth. On the Continent, the Saxon ruler Widukind (also spelled Wittekind) had a son named Wigbert (also spelled Wichbert and Wibreht), who in turn named his own son Waltbert.

Not only do I have to change Acha’s name, but also her daughter, her brother, and her nephews. The challenge: stay mostly true to how Saxons named their children but not confuse the reader. I have a few factors on my side.

My characters are fictitious, which provides a lot of flexibility

The second element of the name (deuterotheme for the academics) could be repeated in children’s names instead of the first part (prototheme).

The themes have variant spellings, and my illiterate characters wouldn’t know how to spell their own names anyway.

Characters go by only one name in this society.

So my first tentative character list:

Leova: my heroine

Derwine: her husband

Leofwine: her son

Sunwynn: her daughter

Leodwulf: her brother

Wulfgar: Leodwulf’s son

Ludgar: his other son

Ebbe: Leodwulf’s wife

So I have four characters with names that not only start with L but use variants of Leof. I thought it was sweet for Derwine to think so much of his wife he would incorporate part of her name into his son’s, but I wonder if it would be easier for the readers if her name were even more different than her children’s.

If I choose the prototheme Neri for my heroine, the character list could be something like:

Nerienda: my heroine

Derwine: her husband

Leofwine: her son

Sunwynn: her daughter

Neriwulf: her brother

Wulfgar: Neriwulf’s son

Nasbert: his other son

Ebbe: Neriwulf’s wife

I like Leova better as a name for my heroine, even if it does mean having four variants of a prototheme, but I would like to hear from readers. What are your thoughts on these characters’ names? I want them to sound like they are from a different time but still be accessible.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like an earlier post about the , a true challenge when writing about historical characters.

October 14, 2012

Review Makes a Great Start to a Writer’s Week

What a nice way to start the week! Blogger Darlene Elizabeth Williams has posted a review of The Cross and the Dragon.

Darlene, the 1st Place Finisher in the 2012 Underground Book Reviews Battle of the Book Review Blogs, writes thoughtful and thorough reviews. Her love of historical fiction goes back to her childhood with the reading of Little Women. On top of her reviews, she is working on her own fiction, one or two novellas on King George IV and his wife, Princess Caroline, before her first full length novel on Princess Charlotte Augusta.

In her review, Darlene writes: “Rendfeld has written a historical fiction novel that remains authentic to the time period, where religion and vows supersedes all else, including love. I thoroughly enjoyed reading The Cross and The Dragon.”

For more, read her full review.

October 10, 2012

4,500 Dead in One Day

One thing I’ve struggled with as a writer is the mass execution of 4,500 Saxon men at Verden in 782, ordered by King Charles (Charlemagne).

To us in the 21st century, our first reaction is that this is barbaric. To my Frankish characters, it’s justice. As I did more research on what led up to this incident for today’s post on Unusual Historicals, I am finding we might be closer to those eighth-century Franks than we would like to believe.

A little context: this execution was retribution for a rebellion in Saxony, part of series of wars between the Franks and the Saxons that started 10 years before. What made 782 distinct was a disastrous battle for the Franks, resulting in the deaths of many noblemen.

In a culture of vengeance, Charles’s own counts would have likely demanded the enemy pay dearly. Perhaps Charles feared if he did not exact a price, the Saxons would be emboldened to do worse.

If we 21st Americans are to be honest, we also want justice when our people are attacked. We could not have let Pearl Harbor or 9/11 go unanswered.

The man Charles probably wanted to kill, Widukind, the instigator of the 782 rebellion escaped. Had Charles captured him, would there have been this mass beheading? We can only speculate.

For more about this incident and what led up to it, visit Unusual Historicals.

Equestrian statue of Charlemagne, by Agostino Cornacchini (1725), St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican. Photo by Myrabella via Wikimedia Commons, used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.

October 4, 2012

Interview with The Dashing Duchesses

Today, Ashlyn Macnamara interviews me on the historical romance blog The Dashing Duchesses about my research, the writing process, and The Cross and the Dragon. Pardon me, I should say Duchess Ashlyn.

The duchesses are a group of historical romance authors who share the history behind their novels and interview fellow authors. I especially enjoyed the post on the history of women’s swimsuits.

Duchess Ashlyn write Regency England and Colonial North America. Her Regency manuscript, retitled A Most Scandalous Proposal, was a finalist in the 2011 Golden Heart contest and will be published by Bantam Books in early 2013.

Among other things, Ashlyn asks about the time period, where I dig up my details, if there are any first-person accounts I particularly enjoyed, and what I found particulary challenging about crafting the story. Find out the answers on The Dashing Duchesses. Hint one of the answers has something to do with the picture below.

Four great resources about the Carolingians (photo by Kim Rendfeld)

October 3, 2012

Wonderful Wednesday for a Writer: Two Reviews of “The Cross and the Dragon”

[image error]Today I was greeted with news that made me both honored and humbled. The Cross and the Dragon received two wonderful reviews. Many thanks to Rachel Massaro of Layered Pages (and to Stephanie Hopkins for arranging the review) and to Casee Marie of Literary Inklings.

Here is a sampling:

From Rachel: “The story is addictive and I found myself not wanting to put the story down.” Read the full review at Layered Pages.

From Casee Marie: “I fell easily into this world and felt wonderfully engaged with the characters, from Alda’s strength to Hruodland’s valor and even Ganelon’s vengeful wrath.” Read the full review at Literary Inklings.

Layered Pages features book reviews and author interviews, including those that are published independently and by small presses. Its founder, Stephanie, is also a reviewer for the Historical Novel Society and consultant with IndieBRAG.

Literary Inklings is a literature blog focusing on classics, adult fiction, and memoirs. It’s a place for book reviews, author interviews, seasonal reading lists and recommendations, information about upcoming new releases, literary discussions and essays by Casee Marie.

October 1, 2012

The Next Big Thing: A Pagan Peasant Family

The latest game for authors in the blogosphere is to tag each other for The Next Big Thing. Once tagged, an author answers a few questions, then tags other writers, with their permission.

Maria Grace, who writes Regency era fiction, tagged me. If Grace’s name sounds familiar, it’s because she recently did a guest post on laundry in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

What is the working title of your book?

The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar.

Where did the idea come from for the book?

As I researched my first book, The Cross and the Dragon, I found mentions of the bitter Frankish-Saxon wars that took place, on and off, for decades. I could only touch on it in The Cross and the Dragon and wanted to explore it further. Originally, my Saxon characters, a peasant family sold into slavery, were going to be secondary, and the novel would focus on two nuns, Elisabeth and Illuna.

I couldn’t make it work with Elisabeth and Illuna, unless I had something really bad happen to them, and I didn’t want to do that. They’re very nice nuns. In the meantime, the Saxons were saying, “Tell our story,” and I gave in.

What genre does your book fall under?

Historical fiction.

Which actors would you choose to play your characters in a movie rendition?

Like Grace, I have a hard time envisioning specific actors for a movie. Perhaps it’s because I’m at my computer for hours on end, mentally centuries and an ocean away, that I don’t keep up with Hollywood.

What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

Only one sentence? I’m still refining this, but here goes. After losing her faith, her home, her husband, and even her freedom in Charlemagne’s 772 war in Saxony, all Acha has left are her children, and she will do whatever it takes to protect them and seek justice against the kin who betrayed them.

OK, it’s a compound, complex sentence, but still only one sentence.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

My first priority is to polish the manuscript. Some of the issues my editor at Fireship Press pointed out in The Cross and the Dragon exist in this one, and I need to research some details like whether playing dice was a common past-time. I’m also considering changing my heroine’s name, since it is similar to Alda, the protagonist of The Cross and the Dragon.

[image error]I’ve not yet decided on a path to publication, but I am leaning toward the small press route. Querying agents is as fun as a root canal, and I’ve not had the pressure of “This had better do well in the first two weeks or else” that Big 6 authors experience. I am happy with how The Cross and the Dragon turned out. I had much more control than I thought possible. My editor’s suggestions improved the story, the cover is beautiful, and people who’ve seen the print edition like the quality.

How long did it take you to write the first draft of your manuscript?

This is difficult for me to calculate. I spent a few months on the version with Elisabeth and Illuna as main characters and threw it away. I’m guessing it was a year after that, but that is only the first draft, which was shoddy, as all my first drafts are. I do many drafts before submission.

What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

This book is unusual in that it gives a voice to pagan medieval peasants. Usually historical fiction, especially set in the Middle Ages, have royalty and aristocrats, people whose names get written down. However, readers who like Mary Stewart or Gillian Bradshaw might also like The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar—and The Cross and the Dragon, for that matter.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

I wanted to give a voice to history’s losers. The Saxons ultimately lost the wars and lost their religion.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

I didn’t have room for this in the one-sentence summary, but it is essential to the story. Allow me to introduce Hugh, a young Frankish solider who slays Acha’s husband, Derwin, in battle. He befriends the Saxon family, especially daughter Sunhilde. They don’t know he killed Derwin, and Hugh doesn’t know the name of the Saxon who died.

Hugh saves Acha’s son from a fanatical Christian and offers to be the champion for Sunhilde, who sees Hugh as a love interest. So the family’s greatest dilemma becomes what to do when they find out Hugh is Derwin’s killer.

If you would like to learn more about Ashes, visit my website for drafts of an excerpt and the first chapter.

Include the link of who tagged you and this explanation for the people you have tagged.

Maria Grace—author Regency era fiction, including the Given Good Principles series, prequels to Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice

Elizabeth Caulfield Felt—author of Syncopation: A Memoir of Adèle Hugo and The Stolen Goldin Violin. You might also remember a post she did about Syncopation’s title character.

Jessica Knauss—author of short stories, including the collection Rhinoceros Dreams, and novels Tree/House, Sail to Italy, and Sail from Italy. Jessica also edited The Cross and the Dragon while she was at Fireship.

Lisa J. Yarde—author of historical novels set in the Middle Ages, including The Burning Candle, On Falcon’s Wings, Sultana, and Sultana’s Legacy.

September 26, 2012

This is the Way We Wash the Clothes…in the 18th and Early 19th Centuries

Today, I am happy to host Maria Grace, author Regency era fiction, including the Given Good Principles series, prequels to Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. After reading Grace’s fascinating post about how laundry was done 200 years ago, I can picture our ancestors laughing at us when we complain about waiting for our machines to just get done already.—Kim

By Maria Grace

I love wash day, don’t you? Ah, no, that’s what I thought. I don’t really either. But at least we can be grateful that, thanks to the modern conveniences of the washer and dryer, it is no longer nearly so arduous as it was for our ancestors.

Maria Grace

Today, we gather the laundry and sort it, more or less, less if you’re one of my teenage sons. If it is a good day, we check for stains, pretreat the stains, then throw it in the machine. Later we wander back to switch it to the dryer, muttering under our breath because the washer doesn’t have a buzzer to let us know it is done. At the sound of the buzzer, we return to dry, sweet smelling laundry, ready to fold and put away. Oh the horrors of it all!

How our 18th and early 19th ancestors century would envy us. For them, laundry definitely did not take place on a weekly basis and when it happened, it was a multiday, all hands on deck experience. The ladies of the house, unless they were very high born, would work alongside the servants (at least until the Victorian era, when more shunned the activity) in order to get the enormous task finished.

Sorting the Laundry

The wealthier a family, the more clothing they possessed, longer they could stretch the time between washdays. Interestingly, the bulk of the laundry consisted of “body linen.” Worn next to the skin, undershirts, shifts, chemises, and the like protected finer garments from skin oils and sweat that soiled clothing more than dirt from the outside. Consequently these fine garments were rarely laundered. These two facts explain why so much silk and wool clothing of the period survives for us to see now. Victorians added removable cuffs and collars to their garments for the same reasons. Looking at my guys’ dress shirts, I can see the wisdom of removable–and replaceable–elements to increase the garment’s lifespan.

Washerwomen in a Grotto,between 1825 and 1830, by Wolfgang-Adam Toepffer (1766-1847)

Laundry days were carefully planned out and executed in order to make best use of the resources. The process might begin the night before, with sorting the laundry. Lights, darks, flannels, calicos, and fine clothing would all be separated and a special pile dedicated to the most heavily soiled items. Often, the dirtiest laundry was set to soak in soapy water or lye the night before the actual process began to minimize the time and effort spent scrubbing the next day. All this sounds rather familiar, but the real work has not even started yet.

Getting Ready to Wash

Firewood might be gathered the day before, but if not, the laundress would need to move 150-200 pounds of wood to the laundry site to feed fires sufficient for a moderate estate’s laundry. That alone sounds like a day’s worth of effort, but for her it was only the beginning. Once wood was gathered and fires started, water had to be hauled to fill the copper boiler and additional wash and rinse basins.

Laundresses preferred copper boilers because they did not rust and stain the clothing the way iron would. The typical boiler would need 20-40 gallons per load with an additional 10 gallons for scrub and rinse water. Depending on the location of the water source, this process alone could require miles of walking burdened with heavy yokes of water by the time the day was over.

Of Lye and Laundry Bats

A Woman Doing Laundry, date unknown, by Henry Robert Moreland (1716-1797)

The laundress placed clothes in boiling water to loosen dirt, agitating them by hand with a washing bat, a 2- to 3-foot-long wooden paddle. After a quarter of an hour in the boiler, she removed the articles to a large basin of warm water to treat any remaining soiled areas with lye soap or other stain treatment.

A variety of preparations might be used on stained clothing. Chalk, brick dust, and pipe clay were used on greasy stains. Alcohol treated grass stains and kerosene, bloodstains. Milk was thought to remove urine stains and fruit. Ironically, urine, due to the ammonia content was often used for bleaching as were lemon and onion juice. Makes modern eyes water just thinking about the process.

To prevent fading, colored garments like calicos were not soaked or washed with lye or soda. They were washed in cold or lukewarm water by hand, rather than agitated with a bat. Ox-gall might be added to the water to help preserve the color.

Obtaining ox-gall meant sending a glass bottle to the butcher, who would drain the liquid of cows’ gall bladders into it. Doesn’t that sound like what you want to add to your next wash cycle? Yeah, me too. If that wasn’t enough, an article that needed starching would be dipped in water that potatoes or rice had been cooked in and saved for laundry day. Laundresses were cautioned to make sure that the starch water had not soured or gone moldy before dipping clothing into it. Just one more appetizing thought to add to our washday pleasantries.

Out of the Wash and on to Drying

Box mangle, found in Oslo, Norway (photo by Tore Torvildsen)

Finally, after boiling, washing and rinsing, garments had to be prepared for drying. To speed drying, excess water had to be removed from the wet fabric. A wealthy household might employ a box mangle, a large contraption that wound laundry around rollers then rolled a heavy box over them to extract excess water. Few households could afford such a luxury.

More often, two people would work together to wring the water from the laundry by twisting. Afterwards, clothes would be hung on clotheslines (usually without clothespins), bushes, hedgerows, wooden frames or laid over the lawn to dry. Inclement weather forced drying inside to kitchen and attic spaces.

As if this was not enough, after the laundry finally dried, nearly every article required pressing of some form. But the history of ironing is a subject for another post.

(All images in this post are in the public domain or used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

References

Kristina Harris. Victorian Laundry (or, Aren’t You Glad You Didn’t Live Then?)

The Complexities of Wash Day in the 18th Century

Michael Olmert. Laundries: Largest Buildings in the Eighteenth-Century Backyard

Victoria Rumble. Victorian Era Laundry & Housekeeping

Free Google Books digitized originals

Madam Johnson’s Present Every young woman’s companion in useful and universal knowledge (1770)

Every Woman Her Own House-Keeper (1796)

About Maria Grace

Though Maria Grace has been writing fiction since she was 10 years old, those early efforts happily reside in a file drawer and are unlikely to see the light of day again, for which many are grateful.

She has one husband, two graduate degrees and two black belts, three sons, four undergraduate majors, five nieces, six cats, seven Regency-era fiction projects and notes for eight more writing projects in progress. To round out the list, she cooks for nine in order to accommodate the growing boys and usually makes 10 meals at a time, so she only cooks twice a month.

She can be contacted at author (dot) MariaGrace (at )gmail (dot) com. You can find her on:

Facebook: facebook.com/AuthorMariaGrace

Amazon: amazon.com/author/mariagrace

her website, AuthorMariaGrace.com

If you like Grace’s post on laundry from 200 years ago, you might also like a deleted scene from my second, yet-to-be published novel, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, set in the days of Charlemagne.—Kim