Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 32

April 26, 2013

Education or Entertainment? Read the Interview.

Today, I am visiting with author J.A. Beard for an interview at his blog, Unnecessary Musings. J.A.’s titles include the Regency paranormal romance A Woman of Proper Accomplishments and YA urban fantasy The Emerald City.

J.A.’s questions are well-researched and thought provoking. Here is a sampling:

Please tell us how you approached the balance of fact and fiction, especially given that your basis is a historical legend that in of itself has some fictionalized details of the events and people it is about.

The period your book covers seems less popular than later, and for that matter, earlier periods of European history. Why do you think that is?

Do you see historical fiction as an educational tool or merely an entertainment tool? If the former, what advantages do you think it has in that regard?

Visit J.A. Beard’s Unnecessary Musings for the answers.

A 14th century depiction of the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, as portrayed in The Song of Roland. I borrowed from the poem in creating The Cross and the Dragon (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

April 22, 2013

When Treason Serves a Literary Purpose

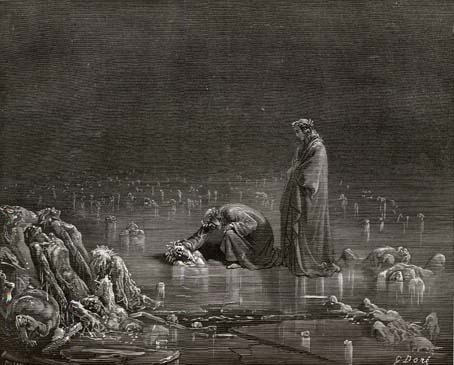

A 19th century illustration of the Inferno by Gustave Dure (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

When Unusual Historicals sought authors to sign up for this month’s “Traitors and Turncoats” theme, Ganelon of The Song of Roland came to mind. His legacy as a traitor is so strong that two centuries after the poem was written, Dante envisioned him in the lowest level of hell, where it’s frozen over. His fate is not as awful as Judas’s but not by much (for more, see Tinney Heath’s guest post about Dante’s vision of Charlemagne and Roland in the afterlife).

Ganelon is perhaps named after a real ninth-century bishop who switched alliances among Charlemagne’s grandsons, but the character in the poem is fictitious. There was no traitor at the 778 ambush at the Pass of Roncevaux, nor were the perpetrators Muslim.

So I don’t feel so bad about making Ganelon a loathsome suitor to my heroine, Alda, but not a traitor. Having him commit treason didn’t serve my purposes.

But it sure served the purposes of the poet who wrote The Song of Roland in the late 11th century. Perhaps the poet was trying to say something about his country’s military superiority around the time of the first Crusade and draw religious parallels. Visit Unusual Historicals for more.

April 15, 2013

Did They Have (Name the Ingredient) Then?

An absolutely tantalizing idea from online book review magazine InD’Tale: authors are invited to submit a recipe with a photo, preferable with the author in it. (Fellow authors, if you would like to submit a recipe, contact Melody Prat at melodyprat (at) indtale (dot) com.)

Food is a favorite subject of mine, and soon I will submit a recipe for beef stew. But I would like to have it close to what people in the eighth-century Francia and Saxony, the settings for my novels, might have eaten, especially if it fed a peasant family. For peasants, beef stew would have been a treat. They were too poor to eat meat every day.

Animals on a peasant farm lived longer than those belonging to the nobility. The peasants were apparently letting the animals get as big as possible before the slaughter. When meat was available, peasants were more likely to have beef than pork. Beef could come from an ox that had broken its leg or was otherwise unable to pull a plow or cart. Or it could be slaughtered in late fall because there was never enough fodder to sustain all the animals through the winter.

With that in mind, let’s look at the ingredients.

Some assembly required.

Chuck roast. Close enough. Even if I knew how cattle were butchered in the Middle Ages, it would be impossible for me to re-create the beef. The animals themselves would have been different. For instance, the popular Black Angus is a Scottish breed that goes back to the 19th century, and it has been improved since then.

Livestock also lived under different conditions than they do today. Cattle spared from the fall slaughter would have spent the winter in a byre and grazed in the field allowed to grow fallow in the summer.

Beer or ale. Of course. It was the breakfast beverage of choice.

Barley. Most stews would have grain, and peasant ate barley and rye. I will have to compromise and use pearled barley. Because of the barley, I am skipping the flour usually used as a thickener.

Herbs. Could use these fresh or dried, depending on the time of year. Parsley, thyme, and basil are among the choices.

Choice of vegetables is determined by time of year, too. By late fall, onions, garlic, carrots, radishes, and turnips would be harvested and in storage. The root cellar could also include celeriac, but since I live in a small Indiana town, I will substitute celery.

Mushrooms. Medieval folk could have found some in the woods, and mushroom can be dried for later use. Note to anyone considering wild mushrooms: Get them only from someone who knows what they are doing and has hunted mushrooms a long, long time. As in the mushroom hunters have gray hair and wrinkles. Lots of both. If you get the wrong mushroom, you might need a new liver. Seriously.

Green peas. A colorful, tasty addition, which I usually use frozen. I’m not above cheating, but peas are a spring crop. If the scenario is late fall, the only ones available in the fall during the Middle Ages would have been dried, assuming they were not already eaten.

Potatoes. Out of the question. Those are a New World food.

The challenge: can I create a dish similar to what medieval folk would have eaten but still be delicious to a modern palate? Stay tuned.

For a great source for food history, visit foodtimeline.org.

April 11, 2013

‘The Cross and the Dragon’ Visits a Virtual Book Fair

Welcome to the virtual stall for The Cross and the Dragon at the Historical Novelists 4-Day Book Fair, April 12-15. As of this writing, about 40 authors are participating in the fair, and I am thankful to have this opportunity to join them.

Welcome to the virtual stall for The Cross and the Dragon at the Historical Novelists 4-Day Book Fair, April 12-15. As of this writing, about 40 authors are participating in the fair, and I am thankful to have this opportunity to join them.

The Cross and the Dragon

A tale of love in an era of war and blood feuds.

A tale of love in an era of war and blood feuds.

Francia, 778: Alda has never forgotten Ganelon’s vow of vengeance when she married his rival, Hruodland. Yet the jilted suitor’s malice is nothing compared to Alda’s premonition of disaster for her beloved, battle-scarred husband.

Although the army invading Hispania is the largest ever and King Charles has never lost a war, Alda cannot shake her anxiety. Determined to keep Hruodland from harm, even if it exposes her to danger, Alda gives him a charmed dragon amulet.

Is its magic enough to keep Alda’s worst fears from coming true—and protect her from Ganelon?

Inspired by legend and painstakingly researched, The Cross and the Dragon is a story of tenderness, sacrifice, lies, and revenge in the early years of Charlemagne’s reign, told by a fresh, new voice in historical fiction.

Interested? Visit kimrendfeld.com to find out where you can get your copy of The Cross and the Dragon, whether you live in the U.S., Canada, or the U.K. Or read excerpts of the reviews.

Want to read more before deciding? Check out this excerpt from the book.

Late August 773, King Charles’s assembly in Geneva

Alda wished she did not loathe the man her brother wanted her to marry.

She glanced at Count Ganelon of Dormagen, sitting to her left at dinner. When she had met him two months before at Drachenhaus, her home many leagues to the north, she had thought him the handsomest man in Francia. Muscular, with broad shoulders and well-formed legs, he had a face that could have been chiseled from marble, topped by a cap of pale blond hair. In the castle’s great hall, his silver medallions gleamed in the light from the walnut-oil lamps and midday sun.

A movement caught Alda’s eye. A cupbearer, head down and shoulders hunched, shuffled toward Ganelon. No older than ten winters, the boy was stick thin and clothed in rags.

How can anyone so mistreat his servants? she thought, wincing.

His face a mosaic of bruises, the boy sipped from the cup and placed it in front of Ganelon. Alda looked away, disgusted with Ganelon and still seething over this morning’s argument with her brother, Count Alfihar of Drachenhaus. Alfihar had ignored her protests, insisting that she did not need to like Ganelon to marry him. No, she didn’t, she admitted to herself, but she wanted to be able to suffer her husband’s company.

She turned her head toward the roasted venison, steaming in front of her on the slab of stale bread that served as a plate. Enticed by the aroma, she tore into the meat with her eating knife.

Ganelon sneered. “I never would have guessed a frail-looking girl like you would have such an appetite.”

Alda’s pale cheeks flushed. She wished she could think of a cutting reply. Any mention of her weight vexed her. She had tried to make herself plump, but no matter how much she ate, she could not add to her hips or breasts. Finally, her words came out in a grumble. “Obviously, I am not frail.”

“You are lucky anyone would wish to marry you. You are so thin you look like a peasant in disguise. Even that servant beside you has more flesh than you.”

The heat of a blush spread over Alda’s face and down her neck. Veronica, her servant and companion, had a fuller figure, but no man with manners would point it out. Why would Ganelon insult her? Baring her teeth, Alda stabbed the meat, wishing it could be Ganelon’s face.

To her right, Veronica nudged Alda. “A pity God blessed Count Ganelon with good looks instead of a good brain,” she whispered. “Most men flatter women they want to marry.”

Alda covered her mouth to suppress a giggle.

“Why do you allow your servants to eat with you?” Ganelon asked contemptuously.

“Her name is Veronica.” Alda’s forest green eyes flashed. “She is my foster sister and my dearest friend.”

Laying aside her knife, Alda squeezed Veronica’s hand under the table. How could Ganelon say such a thing about the young woman whose mother had nursed both of them?

“My servants stay away from the table,” Ganelon said. “I cannot bear to watch them eat like beasts.”

“Perhaps you should give them more food,” Alda snapped. Her gaze fell to the jeweled hilt of his eating knife. “My brother says you can afford it.”

“That is not your concern,” he retorted.

Alda’s nostrils flared. She did not know how she was going to endure Ganelon through dinner, let alone the rest of her life. She gazed to her right. Alfihar was dining five paces away with their uncles and the man she wanted, Prince Hruodland, heir to the March of Brittany and King Charles’s kinsman.

Hruodland’s features were plainer than Ganelon’s but still pleasing. At perhaps twenty-one winters, slightly older than Alfihar, Hruodland was a tall man with the warrior’s build that came from wearing armor and wielding a sword. He had dark brown, almost black, piercing eyes, a long nose, a square jaw, and dark hair that fell to his shoulders. She smiled as she remembered meeting him in the castle’s courtyard yesterday morning and later talking with him long into the night.

Veronica’s whisper broke into her thoughts. “Stop gawking at Hruodland! It will provoke Count Ganelon.”

Alda’s lips drew into a thin line, but she followed Veronica’s advice and turned her head. This meal was difficult enough without Ganelon’s jealousy. Glancing at Ganelon, she shuddered. His icy blue eyes were full of malice.

Want to add The Cross and the Dragon to your library? Find out where you can get a print edition or e-book in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K.

If you’d like to check out more authors writing about a variety of historical periods, visit the Historical Novelists 4-Day Book Fair.

April 5, 2013

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

It’s the first Friday of the month, which means it’s time for another guest post about the history of the theory of atoms from physics professor and my dad, Dean Zollman. Here, we find ancient knowledge preserved in the medieval Islamic world.—Kim

By Dean Zollman

Many years ago, before the way to find information was typing on a computer, I needed to verify some historical information for a textbook that my wife, Jackie Spears, and I were writing. As I was browsing in a library, I came across Alan Franklin’s small book, The Principle of Inertia in the Middle Ages. As a physicist with some knowledge of the history of my subject, the words “inertia” and “Middle Ages” seemed incongruous.

Many years ago, before the way to find information was typing on a computer, I needed to verify some historical information for a textbook that my wife, Jackie Spears, and I were writing. As I was browsing in a library, I came across Alan Franklin’s small book, The Principle of Inertia in the Middle Ages. As a physicist with some knowledge of the history of my subject, the words “inertia” and “Middle Ages” seemed incongruous.

I knew that Aristotle got it wrong. He thought that an object’s natural state was sitting at rest. Thus, it took a force to keep an object moving, even at a constant speed in a straight line. My view was that Aristotle’s physics held sway until Galileo and Newton explained that an object keeps moving at a constant speed in a straight line or stays at rest unless an external force acts on it. The object’s inertia is this tendency to keep doing what it has been doing unless something forces it to change.

Intrigued, I read Franklin’s book and learned that science did not stop with Aristotle and restart after the Middle Ages; instead a flourishing scientific endeavor was taking place in the Middle East and Northern Africa while Europe was suffering through the so-called Dark Ages.

Scholarship was a major undertaking in the Middle East during approximately the eighth to 16th centuries. Some people call the science from this time Islamic Science because it is closely connected to the areas of the world that practiced Islam. Others argue that it should not be associated with a religion and prefer Arabic Science because the language of scholarship was Arabic even though many of the scholars were not Arabs. Independent of the name, scientific strides were accomplished in many areas including astronomy, medicine, mechanics, optics, and chemistry.

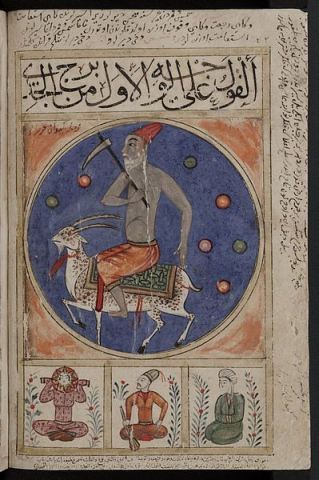

The Kitab al-Bulhan is a composite astrology/astronomy/geomancy Arabic manuscript from the late 14th century (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons).

In addition, in the eighth century, paper manufacturing was brought from China—to the Middle East but not Europe. Books became relatively inexpensive, and over about two centuries, a major translation effort was completed. Much of the classic works from Greece, Rome, India, and Persia were translated into Arabic and distributed throughout the lands that were under control of the Arabic Empire.

As you know from reading The Cross and the Dragon, at that time this territory included parts of Spain. So when Charlemagne took his army to Spain to help a Muslim ally overthrow the emir of Córdoba and prevent an invasion of Francia, he would have been just a little early to have seen some of these books or met some of the Arabic scholars. Of course, Charlemagne had other things on his mind than intellectual discussions with Saracens.

Atoms did not play a major role in Arabic science. However, Islamic philosophers had some of the same problems as early Christians. How does one reconcile atoms that are eternal with God creating the universe? The Kalam, an Islamic school of philosophical theology, was able to deal with this and other issues by developing a set of twelve propositions for the atom. I won’t try to describe all of them here.

One proposition states that time comes in instances which are separated from each other. Another involves properties, called accidents, of substances. These accidents include properties such as color, smell, motion, or rest, but also life and death.

The most important proposition is that accidents do not cross instances in time. Instead it is the role of God to create the accidents at each instant. For something to continue to exist as it did in the previous instant, God must re-create the accidents. Otherwise, the substance would cease to exist. Thus, creation seems to be happening continuously.

As I understand this (and I don’t pretend to understand it well), a pile of snow is white because God has created the accident whiteness in each atom of the snow. God must at each instant in time re-create this whiteness for the snow to remain white. Thus, this arrangement solves the problem of creation and eternal atoms because God is always acting to maintain the properties of atoms.

As I said at the beginning, this (or any) view of atoms was not a central part of Arabic science. Many of the strides made in scientific disciplines during the Middle Ages later became part of Western science. The “portal” through which many of them passed was the Islamic culture in Spain. As the Dark Ages subsided, many of the classic Greek, Roman, and Indian works that were then available in Arabic because of the eighth through 10th century translations were translated once again. This time the translation was from Arabic into Latin. Thus, the scholarship in the Middle East may have saved some classic works from being lost.

At the same time during the late Middle Ages some people were rediscovering some of the classics, such as Roman poet Lucretius’ The Nature of Things, which describes the basic ideas of the Greek atoms. This rediscovery is a story that I will save for next time.

Previously:

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received three major awards—the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and American Association of Physics Teachers’ Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

April 2, 2013

A Special, Virtual Book Fair for Historical Novelists

Next weekend (April 12-15), Outtakes will become a virtual stall for The Cross and the Dragon at the upcoming Historical Novelists 4-Day Book Fair. As of this writing, about 30 novelists are participating in the fair, and I am thankful to have this opportunity to join them. Fellow historical novelists, there is still time to sign up. Simply follow the directions on Francine Howarth’s post about the fair.

March 22, 2013

Carolingian Queens’ Role More Complex Than It Seems

Bertha Broadfoot, 1848, by Eugène Oudiné at Luxembourg Garden, Paris. (copyrighted photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons).

Eugène Oudiné’s Bertha Broadfoot in Luxembourg Garden, Paris, was created in 1848, more than 1,000 years after its namesake’s death, yet the statue holding a miniature man on a throne captures the essence of her personality, a strong woman who supported her upstart husband as he seized the crown. The statue also depicts the role of Carolingian queens in eighth and ninth century Francia.

A ninth-century treatise said the queen’s role was to free the king from household affairs and let him focus on matter in his realm, but when the personal and political are intertwined, that role is far more important and complex than it seems.

Please visit Oh for the Hook of Book for my guest post about the role of Carolingian queens and why Women’s History Month is important. And while you’re there, check out host Erin Al-Mehairi’s review of The Cross and the Dragon and our in-depth conversation.

You might also like:

A Mystery: Why Did the King Want to Divorce the Queen

Hints of Romance between the King and the Queen

March 18, 2013

What’s Real? What’s Imaginary? Check Out the Interview

Today, I am being interview by Samantha Holt, author of medieval romance including The Crimson Castle and the soon-to-be released Borderland Bride.

Samantha asks great questions, including:

Is anything in your book based on real life experiences or purely all imagination?

Is there a part of the story you really liked but had to remove, and if so, could you tell us why?

What does your protagonist think about you? Would they want to hang out with you, their author and creator?

Visit Samantha Holt’s blog for the answers to these questions and more.

March 13, 2013

Medieval Folk Would Think Our Lent Was Easy

Go back 1,200 years to eighth-century Francia – the setting for The Cross and the Dragon and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar – and you will find Christians took Lent seriously. No meat. No eggs. No dairy. Only one meal a day around 3 p.m., and that was a relaxation of not eating until evening. Sort of like being a vegan with the exception of fish.

Salmon like this one would have been acceptable at the dinner table during Lent (Fish and Wildlife Service image via Wikimedia Commons).

Lent might not have made that much of a difference in what commoners had on their tables. They could not afford to eat meat every day anyway, and food stores likely were running low at this time of year. Yet the folk found a few loopholes. The term fish also covered frogs, beaver tails, and barnacle geese (believed to have hatched from barnacles).

If you were young, old, sick, or pregnant, you were not required to fast. One does wonder whether claims of illness rose during Lent.

And the self-denial did not affect only your diet. You were supposed to abstain from sex, even with your spouse (although the penance for the act was less if you were drunk).

Most of the faithful followed the dietary rituals because that is what the priests told them to do to avoid any more days in purgatory or worse spend eternity in hell. Yet these rituals must have also made Easter all the more joyous.

Sources

Catholic Encyclopedia on new advent.org

Recreating Medieval Lent, Agnes deLanvallei (Kathy Keeler)

Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne, Pierre Riche, translated by Jo Ann McNamara

Charlemagne: Translate Sources, P.D. King

March 7, 2013

Strong Is Sexy

[image error]Today, Alda, the protagonist of The Cross and the Dragon, is the Strong is Sexy Heroine of the Week at Book Babe, a blog hosted by author Tara Chevrestt.

Here is how Tara describes the assignment: “A blog post/paragraph or two telling me who the heroine is, what book she is in, and what makes her both strong and sexy. It can be ‘she’s strong because she did this… she survived that…’ It can be anything you want, as long as she’s strong in some way.

“What is sexy about her? Let’s make it about more than just nice legs, big breasts, etc. Sexiness is more than physical. It can be her ability to take care of herself, of business, her persistence, something she does for others.”

Visit Book Babe to see how Alda fills the role of this week’s Strong is Sexy Heroine.