Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 33

March 5, 2013

An Interview about Writing, Getting Publishing, and More

Today, I have an SAT (Successful Author Talk, not that test American students dread) with Mindy McGinnis, who writes young adult fiction and hosts Writer, Writer, Pants on Fire.

Among Mindy’s thought-provoking questions are:

Did you have to overcome any fears that first time you sat down to write?

Any advice to aspiring writers out there on conquering query hell?

When do you build your platform? After publication? Or should you be working before?

Find out the answers to these questions and more at Writer, Writer, Pants on Fire.

March 1, 2013

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

It’s the first Friday of the month, which means it’s time for another guest post about the history of the theory of atoms from physics professor and my dad, Dean Zollman. Here, we find arguments about religion and science that will sound awfully familiar to modern readers.—Kim

By Dean Zollman

Today, some Christians accept a literal interpretation of Genesis and thus reject certain scientific constructions such as evolution and cosmology. The situation was little different 2,000 years ago as the early Christian philosophers and theologians contemplated the compatibility between their beliefs and the concepts of atoms as expounded by Democritus, Epicurus, Lucretius, and others.

Today, some Christians accept a literal interpretation of Genesis and thus reject certain scientific constructions such as evolution and cosmology. The situation was little different 2,000 years ago as the early Christian philosophers and theologians contemplated the compatibility between their beliefs and the concepts of atoms as expounded by Democritus, Epicurus, Lucretius, and others.

As I have discussed in previous posts, the Greeks who developed the ideas about atoms stated that the atoms were indivisible and indestructible. An indestructible atom has always been here; it was not created at any particular time in history. This fundamental property of the Greek model of the atom comes in direct conflict with a God creating the universe as described in Genesis.

A church cave in Cappadocia from about from about 1000 AD. (Photo by Dean Zollman)

As an example of early Christian thinking, Basil of Caesarea in Cappadocia, also known as Saint Basil the Great, (c. 329 – 379) stated, “Those who were too ignorant to rise to a knowledge of a God, could not allow that an intelligent cause presided at the birth of the Universe; a primary error that involved them in sad consequences. Some had recourse to material principles and attributed the origin of the Universe to the elements of the world. Others imagined that atoms, and indivisible bodies, molecules and ducts, form, by their union, the nature of the visible world. Atoms reuniting or separating, produce births and deaths and the most durable bodies only owe their consistency to the strength of their mutual adhesion: a true spider’s web woven by these writers who give to heaven, to earth, and to sea so weak an origin and so little consistency! It is because they knew not how to say ‘In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.’” (Homily 1 in The Hexaemeron) St. Basil thus saw atoms and a God who created the universe as incompatible ideas.

(Off topic: I enjoy quoting St. Basil because I visited Cappadocia last July. The ancient churches were caves carved in the soft stone. Many of these structures can be visited. So, maybe I stood in a place where about 1,700 years earlier St. Basil was explaining why the Greek atomists had the wrong idea.)

Creation was only one of several reasons that early Christians had trouble with the idea of matter being made of atoms. For example, another was the atomists view that the material that we can experience is created by atoms randomly colliding with each other. The random part is the problem. God was not random in the design of the heavens and earth.

Then, there is the Eucharist—body of Christ but atoms of bread. I don’t know enough theology to even try to touch that one.

With the rejection of the concepts of atoms almost disappeared from Western thought for the next 15 centuries. Most historians of science say little or nothing about the concept of science during this extended time. Bernard Pullman in The Atom in the History of Human Thought says, “We could even have symbolized this state of affairs by leaving a few pages of this book blank.”

Fortunately, the concept of atoms did not get lost. A few Christian, Jewish, and Islamic philosophers continued the scholarly thought of the Greeks, Romans, and Hindus. We will take a look at some of them during the next couple of posts.

Previously:

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received three major awards—the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and American Association of Physics Teachers’ Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

February 25, 2013

‘A glorious tale’ and more praise for ‘The Cross and the Dragon’

[image error]Many thanks to the reviewers who in recent weeks have told their readers how much they’ve enjoyed The Cross and the Dragon, a tale of love amid the wars and blood feuds of Charlemagne’s reign.

I usually don’t like the idea of being responsible for someone missing sleep, but when that reason is my book, I’ll make an exception. Denise at So Many Books So Little Time writes, “I absolutely loved this book! I haven’t read anything about this period in history so this story was completely new and exciting for me. The characters, romance and the setting sucked me in from page one and I stayed up pretty late a few nights because I couldn’t put this book down.” Visit So Many Books So Little Time for the complete review.

At The Edible Bookshelf, DelSheree Gladden writes, “The depth of reality captured in this book is commendable. The details of the homes, character’s dress, politics, and religious beliefs were all carefully crafted. I had no problem putting myself in the time period and believing the events of the story.” Visit The Edible Bookshelf for the complete review.

Erin Al-Mehairi, host of Oh for the Hook of a Book, writes, “I read it almost in one sitting, during which I could not bear to put it down for fear I would fail Alda, her female protagonist, in her pursuits and that I’d lose the momentum of the exhilaration I was feeling of reading such a wonderful novel. Yes, I loved it!! I was swept away into a glorious tale of a strong young woman and her man, who equally loved her as much during a time when men didn’t always love women as romantically as would be desired.” Visit Oh for the Hook of a Book for the full review and a chance to enter a giveaway for a signed copy.

Also, check out my conversation with Erin, where she asked some thought-provoking questions such as “What do you think really defined love during the Medieval times?” and “What do you feel makes journalists successful when they cross over into fiction work?”

February 20, 2013

Why Religion is Essential to Medieval Fiction

Divine intervention was a real thing in the Middle Ages, especially the days of Charlemagne, the time period for The Cross and the Dragon. When the Franks prayed for a victory, they were literally praying, holding litanies and abstaining from meat and wine (or paying alms).

My guest post on The Edible Bookshelf elaborates on the role religion played in the Carolingian era (eighth and ninth century Europe) and in The Cross and the Dragon.

Visit the Edible Bookshelf

for why I say to neglect religion would be literary malpractice.

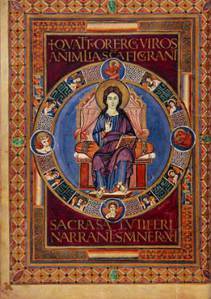

Christ in Majesty from the Lorsch Gospels (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

February 9, 2013

Hints of Romance Between the King and the Queen

It’s an unlikely love story: a teenager and a 35-year-old widowed father of seven. Child No. 8 was on the way, and the man was also twice divorced. The teenager is Queen Fastrada, and the much older man is King Charles, whom we today call Charlemagne.

It’s an unlikely love story: a teenager and a 35-year-old widowed father of seven. Child No. 8 was on the way, and the man was also twice divorced. The teenager is Queen Fastrada, and the much older man is King Charles, whom we today call Charlemagne.

To those who are familiar with Fastrada, she seems to be an unusual choice for a blog hop featuring more than 20 authors telling mushy love stories (see the list below). After all, Charles’s biographer Einhard blames her cruelty as the cause of two conspiracies against the king, including one involving Charles’s eldest son Pepin. Never mind that both sets of conspirators had other reasons to rebel. Or that Einhard never elaborates on what she did. Or that Charles and Fastrada were dead when Einhard wrote those words.

My take on Fastrada is that she was maligned, the victim of a backlash against strong women and the inspiration for my still-in-a-very-rough-stage third novel.

Yet the reason I want to write about this queen is her relationship with Charles. Or more accurately, the relationship the primary sources hint at.

Fastrada’s birth date is not known, but she likely was between the ages of 13 and 19 when she wed Charles in 783, a few months after Queen Hildegard’s death. The probable reason behind the marriage was to solidify a Frankish alliance east of the Rhine when Charles was still fighting the Saxons.

But there seems to be more than politics in the couple’s union. The 787 entry in the Royal Frankish Annals contains this entry: “The same most gracious king reached his wife, the Lady Fastrada, in the city of Worms. There they rejoiced over each other and were happy together and praised God’s mercy.”

Those two sentences are very unusual for Frankish annals. Most of the time, the authors write about wars and politics. They don’t trouble themselves with how a couple felt about their reunion after months apart. Might Fastrada have been overseeing the annals and making sure they included that information?

Ninth century coin with an image of King Charles (from Wikimedia Commons, permission granted under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License)

Another clue of the affection the couple shared comes from Charles himself in a surviving letter to Fastrada, composed before he went to war with the Avars in 791. Charles greets her as “our beloved and most loving wife.” Perhaps that can be dismissed as a flourish by the person who actually put quill to parchment (Charles and the vast majority of Franks couldn’t write), but when you read the letter, you get the impression the greeting is not a mere platitude.

Charles describes the litanies to ensure victory and asks Fastrada to make sure the prayers and rituals are carried out at home, adding that she can decide for herself if she’s well enough to abstain from wine and meat. Gotta like a man who says his wife can make up her own mind.

Then Charles says he is surprised he hasn’t heard from his wife lately. “As to which, it is our desire that you should notify us more frequently concerning your health and other matters.” Not the sentiment of an apathetic husband.

Did Charles and Fastrada’s love survive the heartbreak of his son’s plot to overthrow him? In 794, two years after the conspiracy, the annalists are more concerned with an assembly that Charles held with the pope’s envoys in Frankfurt and the heresy of a cleric named Felix. But the authors mention that Fastrada died there and was buried with honors at St. Albans in nearby Mainz. I can only surmise Fastrada was in Frankfurt because Charles wanted her there.

Their story shows us love can thrive, even where it seems unlikely. (My sources are Carolingian Chronicles, which includes the Royal Frankish Annals, translated by Bernhard Walter Scholtz with Barbara Rogers, and Nithard’s Histories, and P.D. King’s Charlemagne: Translated Sources.)

Many thanks to David Pilling and Maria Grace for organizing this hop. Each participating author in the Hearts through History Hop (listed below) is hosting a giveaway from February 10-16.

[image error]Mine is an e-book of my debut novel, The Cross and the Dragon, which takes place a decade before Charles and Fastrada wed. Featuring the willful and courageous Alda and her beloved husband, Hruodland, it’s a tale of love amid wars and blood feuds (see kimrendfeld.com for more). To enter the giveaway, leave a comment on this post only and provide an e-mail address so I can contact the winner.

To rack up additional entries:

Like my Facebook fan page (please note that Facebook rules prohibit using comments on its platform for giveaways).

Follow me on Twitter.

Say in the comments here that you’d like to receive an e-mail when my second book, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar , is published.

If you do any of the above–or if you’re already a Facebook fan or Twitter follower–just note it in the comments on this post.

Hop Participants

Random Bits of Fascination (Maria Grace)

Pillings Writing Corner (David Pilling)

Sally Smith O’Rourke

Darcyholic Diversions (Barbara Tiller Cole)

Faith, Hope and Cherry Tea

Rosanne Lortz

Sharon Lathan

Debra Brown

Heyerwood (Lauren Gilbert)

Regina Jeffers

Ginger Myrick

Anna Belfrage

Fall in love with history (Grace Elliot)

Nancy Bilyeau

Wendy Dunn

E.M. Powell

Georgie Lee

The Riddle of Writing (Deborah Swift)

Outtakes from a Historical Novelist (Kim Rendfeld)

The heart of romance (Sherry Gloag)

A day in the life of patootie (Lori Crane)

Karen Aminadra

Dunhaven Place (Heidi Ashworth)

Stephanie Renee dos Santos

February 3, 2013

Time Travel in 10 Sentences

Today is the debut of The Backward in Time Blog Hop, where six authors of historical fiction offer 10-sentence excerpts of their work, anything from an already published novel to a work in progress.

[image error]My contribution is from the first chapter of The Cross and the Dragon, where my heroine, Alda, has just finished dinner with Ganelon, the man her brother wants her to marry. Despite Ganelon’s good looks, Alda doesn’t like him and would much rather marry Hruodland.

Ganelon’s scrawny servant was staring at the slab of bread upon which her meat and vegetables had rested. Now it was empty save for the gristle and bone. The child gazed up at Alda. He had the look of a dog begging for food.

“Poor child,” Alda murmured. She reached toward the table and handed the servant the bread.

A meaty hand grabbed her right arm and yanked her a half turn, causing her to stumble. Ganelon was standing over her. Alda struggled to pull away, but his grip was like a hunter’s snare.

“That is my servant!” he shouted, his breath a hot blast reeking of wine.

Many thanks to Jessica Knauss for organizing the hop. Please visit Jessica’s blog for links to the other participating authors, whose periods range from 12,000 BC to the 19th century.

February 1, 2013

Atom Theory in Ancient India

It’s the first Friday of the month, which means it’s time for the next installment of how atom theory evolved. Here, physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman talks about how three schools of Indian philosophy explained what things were made of.—Kim

By Dean Zollman

At about the same time that Democritus and others were developing some basic ideas of atoms in Greece, Indian philosophers were thinking about similar issues. As with the Greeks, the Indian philosophers were thinkers not experimentalists. So, they developed theories of fundamental objects by logic. They concluded that some fundamental building blocks—atoms—existed.

At about the same time that Democritus and others were developing some basic ideas of atoms in Greece, Indian philosophers were thinking about similar issues. As with the Greeks, the Indian philosophers were thinkers not experimentalists. So, they developed theories of fundamental objects by logic. They concluded that some fundamental building blocks—atoms—existed.

Three different schools of thought—Nyaya-Vaisesika, Jainist, and Buddhist—came to similar but slightly different conclusions.

One of the earliest philosophers (about 600 BCE) was Kanada, the founder of the Vaisesika School. Atoms in this school of thought were indestructible and thus could not be divided into smaller objects. They were so small that they could not be perceived by humans. Instead, the atoms combined, and it took a combination of at least three atoms to be apparent. Atoms of the four fundamental substances—earth, air, fire, and water—had other properties such as color, odor, flavor, and touch. Earth and water also had weight.

So the system became rather complex as these atoms combined to create something that could be perceived. To make the system still more complex, atoms were associated with other components of human endeavors that are less easily observed. Thus, Kanada and his followers associated atoms with space, time, the soul, and thoughts.

The Buddhists stuck with just the basic four atoms—earth, fire, water, and air. Their atoms also could only be perceived in combinations. For them, the minimum number of atoms was seven or eight with one atom at the center and the rest surrounding it.

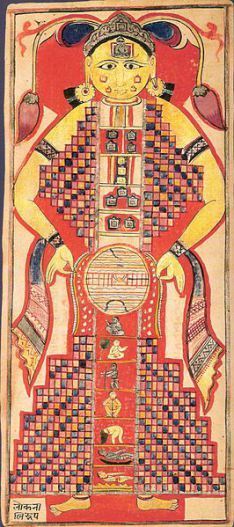

The Shape of Universe as per Jain cosmology in form of a cosmic man, from Samghayanarayana loose-leaf manuscript India, ca. 16th century (public domain image from Wikimedia Commons).

The Jains had a somewhat more complex view of atoms and is, perhaps, the closest to the modern view. Their atoms were, once again, indivisible and indestructible. As with the Nyaya-Vaisesika views, the atoms of the Jains had properties such as color, flavor, and taste.

A connection with modern models is that atoms came in two opposing kinds, and these opposites attracted to make a combination of atoms. For example, humid atoms were attracted to dry atoms; rough atoms to smooth, etc. Any aggregate of two atoms would require a combination of opposites. The system was somewhat like our present view of electrical charge where opposites attract. (Of course, some people think that model applies to some social interactions as well, but that idea cannot be explored with the laws of physics.)

The similarity of the early Indian views of matter with the Greek models have led some to wonder if communication occurred between the philosophers in these early civilizations. Could Democritus have talked with the followers of Kanada?

Of course, we have no way of knowing for certain. But the folks who study these issues carefully have not found any solid evidence that such communication occurred. It seems likely that the early models of the atom were developed independently at about the same time in history. (It might make a good historical fiction to speculate about what a meeting of Greek and Indian atomists would be like. But probably only a few physicists would be interested in reading it.)

For the most part, our modern views evolved from the Greeks, so next time we will start looking at further development of those ideas after the Romans.

Previously

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received three major awards—the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and American Association of Physics Teachers’ Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

January 30, 2013

When Magic Was Real

Today I am visiting Pilling’s Writing Corner to explain why magic has a presence in The Cross and the Dragon.

Regardless of class, most medieval folk believed in magic, and despite the Church officially frowning on it, they would often employ it for healing, protection, or other beneficent purpose. By wearing a charmed amulet, my heroine, Alda, is following a common practice. Please visit Pilling’s Writing Corner to learn more.

My thanks go the blog’s host David Pilling, whose most recent series The White Hawk, covers the War of the Roses from perspective of a middle gentry family. Later, David will appear on Outtakes with a post about why he chose a family of this class to show us this slice of history.

This phylactery (amulet) is from the 13th century, but they were commonly used in the centuries earlier for protection (public domain image provided to Wikimedia Commons by the Walters Art Museum).

January 23, 2013

Surprise! Medieval people bathed.

When I was researching daily life while writing The Cross and the Dragon, I was most surprised to learn that medieval people bathed.

Before reading a section of Pierre Riche’s Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne, I had thought it common knowledge that medieval folk didn’t bathe because they thought it unhealthy. Heck, even teachers repeated this.

Common knowledge, as it turns out, is wrong on this one. Carolingian palaces were required to have baths, and bath houses had a place at abbeys as well.

This month’s theme at Unusual Historicals blog is “Myths and Misconceptions.” I could not resist adding medieval bathing to the mix. Visit Unusual Historicals to learn more.

This 10th century Byzantine work of art includes a depiction of baby Jesus getting His first bath (public domain image provided to Wikimedia Commons by the Walters Art Museum).

January 15, 2013

Should the Saxon War Leader Have Different Colored Eyes?

Widukind memorial in Herford, Germany, rebuilt from an 1899 sculpture by Heinrich Wefing. (By M. Kunz via Wikimedia Commons, used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.)

There is an intriguing story about Widukind, a real-life eighth-century Westphalian Saxon war leader and enemy of Charlemagne, and I am debating whether to use it in my next novel, with the working title The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar.

Most of what we know of the historic Widukind comes from the Franks, particularly the writers of the Royal Frankish Annals. Nowhere do they say what he looked like. But a story gives him an unusual physical feature: heterochromia, eyes of different colors.

In this story, which cannot be verified, Widukind has one blue eye and one black eye. Problem is, I don’t know where this tale comes from. I’ve seen a reference to it only in passing, the most recent one in a book about Nazis. If only for the author’s note, I would love to know the story’s origin.

Today, we would explain heterochromia as a quirk of genetics, but in the Middle Ages, the folk would have seen it as a sign of the supernatural. On top of that, Widukind and his followers worship the pagan Germanic gods. There are no tales of Wodan having only one eye, but his Norse counterpart, Odin, does.

Widukind must have been a charismatic figure, and a sign of the supernatural could be a factor for why Saxons would follow him, even as the two sides inflicted punishing losses on each other.

Widukind is a secondary character in Ashes, which focuses on the fate of a peasant Saxony family sold into slavery (see kimrendfeld.com for my latest draft of the blurb), yet he mentioned throughout the novel.

Should I use this physical feature for Widukind, even if it likely is fictional and even if I can’t track down its origins?