Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 30

July 29, 2013

French Toast: A Treat for Peasants and Aristocrats

Two culinary experiments: French toast for aristocrats (left) and commoners.

The assignment: Participate in a blog hop combining history, food, and writing. How could I possibly say no to an invitation from Ginger Myrick, author of Work of Art: Love and Murder in 19th Century New York and other books?

Here is how the Tasty Summer Reads Blog Hop works: Each author invites up to five other authors to answer five questions about their current summer release or WIP (work in progress for the acronym impaired) and post a tasty recipe that ties into it (links to prior posts below). I have invited Jessica Knauss, author of The Seven Knights of Lara, and Susan Spann, author of Claws of the Cat, to join in the hop, and they should have their recipes up soon, so just click on their names to see what they’re serving up.

First, a little about my current release: The Cross and the Dragon, a tale of love amid the wars and blood feuds of Charlemagne’s reign.

Francia, 778: Alda has never forgotten Ganelon’s vow of vengeance when she married his rival, Hruodland. Yet the jilted suitor’s malice is nothing compared to Alda’s premonition of disaster for her beloved, battle-scarred husband.

Although the army invading Hispania is the largest ever and King Charles has never lost a war, Alda cannot shake her anxiety. Determined to keep Hruodland from harm, even if it exposes her to danger, Alda gives him a charmed dragon amulet.

Is its magic enough to keep Alda’s worst fears from coming true—and protect her from Ganelon?

Now for the Random Tasty Questions:

1) When writing, are you a snacker? If so sweet or salty?

Before I go to my computer, I snack on yogurt or cheese. My cats will sometimes want lap time when I’m writing, and I don’t want to share food with them. However, I often have a beverage nearby, either coffee in the morning and early afternoon, dark beer at night.

2) Are you an outliner or someone who writes by the seat of their pants? And are they real pants or jammies?

My first two novels, The Cross and the Dragon and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, were by the seat of my pants (real ones). I get stuck on outlines. However, the historical events concerning Queen Fastrada, the subject of my third novel (very rough draft stage), provided more structure than I’m accustomed to.

3) When cooking, do you follow a recipe or do you wing it?

After graduating from college and in the early years of my marriage, I would consult The Joy of Cooking and 60-Minute Gourmet, both great for learning the basics. Even then, I would improvise. Many years later (never you mind how many), I wing it for familiar dishes or consult recipes mainly to get general concepts for new things. I rarely even measure anymore.

4) What is next for you after this book?

I recently signed a contract to have The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar (the current title) published with Fireship Press. Ashes, a tale about the lengths a mother will go to protect her children, is a companion to The Cross and the Dragon. Here is the latest version of the blurb.

Can a mother’s love triumph over war?

Charlemagne’s 772 battles in Saxony have left Leova with nothing but her two children, Deorlaf and Sunwynn. Her husband died in combat. Her faith lies in the ashes of the Irminsul, the Pillar of Heaven. And the relatives obligated to defend her and her family sold them into slavery, stealing their farm.

Taken in Francia, Leova will stop at nothing to protect her son and daughter, even if it means sacrificing her honor and her safety. Her determination only grows stronger as Sunwynn blossoms into a beautiful young woman attracting the lust of a cruel master and Deorlaf becomes a headstrong man willing to brave starvation and demons to free his family.

Yet Leova’s most difficult dilemma comes in the form of a Frankish friend, Hugh. He saves Deorlaf from a fanatical Saxon Christian and is Sunwynn’s champion—and he is the warrior who slew Leova’s husband.

5) Last question…on a level of one being slightly naughty and ten being whoo hoo steamy, how would you rate your book?

I’d give the heat level of The Cross and the Dragon a three. There is sex, but we fade to black. There is also an attempted rape, which was necessary for the plot.

And now for the really tasty part: Post your recipe.

There are no surviving recipes from eighth-century Francia. Not a surprise when you remember that most of the population, including cooks, was illiterate. But we know what food the folk grew and could gather in the forest, and we can make some guesses. I was thinking about what people would have on hand at the height of the summer. Peasants would be letting their animals fatten up in the pastures, so meat would be scarce. But they would have eggs and milk.

Two versions of the same dish, French toast, with the one gracing an aristocratic table on the left.

So how about what we call French toast? I checked out one of my favorite sites, foodtimeline.org, and found out that recipes for French toast date back to the Romans and would grace aristocratic tables.

The ingredients would be different. Peasants would have bread made from rye or barley, while aristocrats ate white bread made of wheat flour. Commoners could use fresh herbs in their gardens such as thyme, parsley, dill, or tarragon, but aristocrats could afford imported spices such as cinnamon and nutmeg.

Even the cooking fat might be different. Aristocrats slaughtered their livestock sooner, so they could have lard on hand in addition to butter at this time of year. Peasants would use butter.

So here are two variants of the same recipe.

French Toast (Aristocratic Style)

White French bread, 3 thick slices

2 eggs

3/8 cup milk

1/8-1/4 tsp. nutmeg

1/8 tsp. cinnamon

1/2 T. butter for cooking

1) Put bread on cookie sheet and bake at 300 degrees about 10 minutes to dry it out. (Note to the Anachronism Police: Medieval cooks would’ve done this over a fire, but my oven is electric. And I’m not giving up my nonstick pans and dishwasher either.)

2) Beat the eggs and mix with milk, add the spices

3) Soak the slices in the mixture

4) Place slices in skillet; if you’re so inclined, pour leftover egg-milk mix over slices

5) Fry in butter until a golden brown

6) Serve with honey

French Toast (Peasant Style)

Rye bread, 3 slices

2 eggs

3/8 cup milk

1 tsp. fresh herb such as thyme, parsley, tarragon, or dill

1 clove garlic, minced

1/2 T. butter for cooking

1) Put bread on cookie sheet and bake at 300 degrees about 10 minutes to dry it out. (See note to Anachronism Police above.)

2) Beat the eggs and mix with milk, add the herbs

3) Soak the slices in the mixture

4) Heat pan, melt the butter, add the garlic and cook until softened, about 10 seconds (less if the pan is really hot)

5) Place slices in skillet; if you’re so inclined, pour leftover egg-milk mix over slices

6) Fry slices in butter until a golden brown, and it’s ready to serve with salt

Check What These Authors Are Serving at the Tasty Summer Blog Hop

Christy English

Donna Russo Morin

Nancy Goodman

Lauren Gilbert

Lucinda Brant

Prue Batten

Anna Belfrage

Ginger Myrick

Jo Ann Butler

Kim Rendfeld (You are here)

Cora Lee

Jessica Knauss

Susan Spann

July 25, 2013

Tetta: A Gentle Soul Who Was Important in Her Day

A figure of an 1800 Benedictine nun at Museum für Klosterkultur, 2009 photo by Andreas Praefcke, released to public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Amid the violence of the Middle Ages, there were gentle souls who practiced and preached mercy. Saint Tetta apparently was one of them.

Yet she is a mystery. The sister of a king, this eighth-century Anglo-Saxon abbess was important in her day. At Saint Boniface’s request, Mother Tetta sent nuns to today’s Germany to solidify Christianity. Some of her disciples also become saints, but little information about her survives. In fact, I’m cheating with this photo because I could not find any image of Tetta.

But we have a few clues. Check out today’s post on English Historical Fiction Authors to learn more.

July 22, 2013

Forthcoming: ‘The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar’

Kim Rendfeld is pleased, ecstatic, thrilled, and tickled to death to announce that she has received a signed contract from Fireship Press for her second novel, now titled The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar.

OK, I would have rolled my eyes at that lead when I was a journalist, but I am truly excited about this project, a companion to The Cross and the Dragon. Details have yet to be worked out, but check out the latest version of the blurb:

Can a mother’s love triumph over war?

Charlemagne’s 772 battles in Saxony have left Leova with nothing but her two children, Deorlaf and Sunwynn. Her husband died in combat. Her faith lies in the ashes of the Irminsul, the Pillar of Heaven. And the relatives obligated to defend her and her family sold them into slavery, stealing their farm.

Taken in Francia, Leova will stop at nothing to protect her son and daughter, even if it means sacrificing her honor and her safety. Her determination only grows stronger as Sunwynn blossoms into a beautiful young woman attracting the lust of a cruel master and Deorlaf becomes a headstrong man willing to brave starvation and demons to free his family.

Yet Leova’s most difficult dilemma comes in the form of a Frankish friend, Hugh. He saves Deorlaf from a fanatical Saxon Christian and is Sunwynn’s champion—and he is the warrior who slew Leova’s husband.

Interested? Read drafts of an excerpt or the first chapter. And if you’d like me to let you know when it’s available, leave a comment below or e-mail me at kim [at] kimrendfeld [dot] com.

In the meantime, you might occasionally see some news about The Cross and the Dragon. On Friday, I had a nice chat with David William Wilkin, who writes in the Regency era. His questions include what moved me to become an author and what was most challenging about writing the book.

The Cross and the Dragon also continues to receive praise. Lucy at Enchanted by Josephine Art and History Salon writes that The Cross and the Dragon is “a novel busting with impeccable details that carried me vividly into medieval times. A wonderful debut for Kim Rendfeld!”

Emma at Words and Peace rated the novel “OMG! You must read this NOW!” Here is a snippet from her review: “I really enjoyed this book a lot. I felt it was extremely well researched, historically speaking, but also with lots of details on daily lives, on food and clothes, for instance. The characters, both men and women, soldiers, wives or nuns, have very strong characters and are richly defined.”

July 19, 2013

Hatchard’s Bookshop: A Regency Bookworm’s Paradise

Today, I am glad to host Grace Elliot, author of historical romances, including Verity’s Lie. Here, Grace discusses options available for book lovers during the Regency. – Kim

By Grace Elliot

If you are visiting this blog, then it’s likely you are a bookworm, and a history loving one at that! But if you lived in the 18th century, then your addiction could be difficult to feed – unless you were wealthy.

If you are visiting this blog, then it’s likely you are a bookworm, and a history loving one at that! But if you lived in the 18th century, then your addiction could be difficult to feed – unless you were wealthy.

Low priced books did exist, in the form of chapbooks. These were mass-produced 24-page booklets with a woodcut illustration on the front cover. The latter did not necessarily reflect the content, for example, the story of Dick Turpin had a Turk with a scimitar on the front cover. Chapbooks were retellings of folk stories such as Robin Hood or Tom Thumb, or accounts of sensational stories such as the criminal Jack Sheppard. Chapbooks were at their most popular in the 18th and 19th centuries, and were sold by street vendors who also touted sheet music and broadsides (single sheet reports of crime, gossip and deathbed confessions).

Chapbooks were cheap and designed for the masses; for those with money at the luxury end of the market were professionally printed books. To some extent these expensive books were fashion items because they manufactured either bound or unbound – if the latter, the purchaser could choose a binding to match his library décor!

What is perhaps surprising is the number of bookshops that existed as early as 1700. At the beginning of the 18th century it is estimated there were 200 booksellers operating in the 50 largest towns. By 1790, this had increased to 1,000 shops in 300 towns. That said, these shops sold diverse goods and the card of “William Owen, Bookseller” is illustrated with bottles – perhaps hinting that his primary trade was not paper goods.

The inability of booksellers to survive selling books alone was because of the price. In the 1770s a complete set of Shakespeare cost £3 at a time when a teacher earned £12 a year. A curate’s entire salary of £20 a year, could buy 12 novels. However, some members of the upper classes were happy to keep prices high, to prevent lower classes becoming infected with unsuitable ideas for their station. It was a perfectly conventional assumption at the time to think that knowledge was a dangerous commodity. Indeed, an attorney general wrote to one author:

“Continue…to publish…in octavo form [a luxury format], so as to confine it to that class of readers who may consider it coolly; so soon as it is published cheaply for dissemination among the populace it will be my duty to prosecute.”

Hatchard’s was one place a Regency era book lover could find something to read – if they could afford books.

So what of bookshops? To this day, you can visit Hatchard’s bookshop in Piccadilly and get a flavour of what a 19th century bookshop was like. Founded in 1797, Hatchard’s is the oldest bookshop in London and welcomed Jane Austen, Byron and Disraeli amongst its customers. Still trading today, the creaky wooden floors, quaint curved staircases and floor-to-ceiling books evoke a bygone atmosphere. Indeed, in my new release, Verity’s Lie, it is one of the heroine’s favourite haunts and she pays it a visit…with unexpected consequences.

Excerpt from Verity’s Lie

Verity suppressed a smile. If only she too could be free of Miss Mowlam, even for half an hour, but alas it was not to be; however, a different kind of escape waited within Hatchard’s book shop.

This was one of Verity’s favorite places. To browse the window display, which was crammed with books of all sizes with leather spines tooled in gilt, brought it own type of joy. The shop’s long frontage comprised central doors flanked by bay windows, and Verity approached it with anticipation. Her eyes danced from volume to volume, taking note which to ask for once inside.

This was one of Verity’s favorite places. To browse the window display, which was crammed with books of all sizes with leather spines tooled in gilt, brought it own type of joy. The shop’s long frontage comprised central doors flanked by bay windows, and Verity approached it with anticipation. Her eyes danced from volume to volume, taking note which to ask for once inside.

Browsing the window brought her to the neighboring store, and it was then she noticed a chalk drawing on the pavement.

Curious, she stooped to examine a lively caricature of the Prince Regent, accurate to the popping waistcoat buttons over a burgeoning belly. A boy knelt over the sketch with chalk in one hand and charcoal in the other. Verity was shocked by the child’s appearance: barefoot and patched breeches held up with string.

He glanced up. “Please, miss. Spare a coin, miss?”

There was raw need written large on his face. The boy, she realized, was younger than she’d originally supposed.

“Where are your parents?” she asked gently.

“Dead, miss.” His tone flat and matter-of-fact.

“Where do you live?”

The boy’s gaze dropped to the ground. “Any where’s I can, miss.”

She frowned at his matted hair and ragged clothes. While growing up, crying herself to sleep for the want of her mother, she had always had food and shelter, but this child had nothing. With trembling fingers she pulled at her reticule’s drawstring.

“Who looks after you?” she persisted. A shadow fell across the edge of her vision.

Grace Elliot leads a double life as a veterinarian by day and author of historical romance by night. Grace lives near London and is passionate about history, romance and cats! She is housekeeping staff to five cats, two sons, one husband and a bearded dragon (not necessarily listed in order of importance). Verity’s Lie is Grace’s fourth novel. Find out more about Grace at her blog, Fall in Love With History, her website and her Amazon author’s page. You can also connect with Grace on Twitter @Grace_Elliot and Facebook.

Grace Elliot leads a double life as a veterinarian by day and author of historical romance by night. Grace lives near London and is passionate about history, romance and cats! She is housekeeping staff to five cats, two sons, one husband and a bearded dragon (not necessarily listed in order of importance). Verity’s Lie is Grace’s fourth novel. Find out more about Grace at her blog, Fall in Love With History, her website and her Amazon author’s page. You can also connect with Grace on Twitter @Grace_Elliot and Facebook.

July 12, 2013

Help Wanted: What Did an 8th Century Portable Cradle Look Like?

It has been vexing me since I first saw the phrase: portable cradle.

I came across it while reading a translation of a medieval biography of Charlemagne’s son Louis the Pious. The Astronomer says Louis was being hauled around in a portable cradle when his dad named him king of Aquitaine in 781. In fact, he was carried in a portable cradle some more until reaching the city of Orleans, where he got a horse and weapons appropriate for his age. At 3 years old, that’s a wooden sword, just in case Louis doubted his purpose in life.

A portable cradle is lovely detail for a novelist to include, and it lends the story authenticity. But what the heck did one look like? The Astronomer doesn’t say, but most medieval writers didn’t bother with what their audience would already know.

I have flipped through countless websites and Google Books and cannot find an answer.

I’m ruling out one medieval picture someone kindly shared with me on Facebook – a woman transporting an infant in a cradle on her back. It’s a full-size cradle, not at all like the Native American invention for carrying a baby on one’s back, and she looks just miserable. I cannot believe anyone, no matter how devoted, would have enough stamina to transport an infant or toddler in that fashion 15 miles a day, especially when the family could afford the much-stronger, and more prestigious, horses.

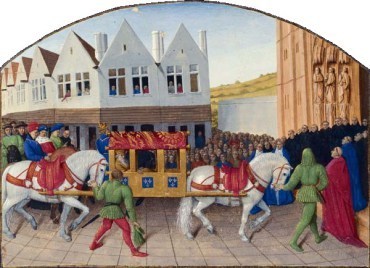

Entrée de l’empereur Charles IV à Saint-Denis, Grandes Chroniques de France, enluminées par Jean Fouquet, Tours, vers 1455-1460 (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

Did the Carolingians have a contraption to transport newborns on the pommel of a horse and then use a litter on horseback when the children were older, as a 15th century Middle Eastern tribe did? Was a portable cradle a sort of playpen on wheels? Was it a litter carried by two horses, similar to what’s depicted in this 15th century picture? A litter would have provided a more comfortable ride on rough roads.

I mentioned a portable cradle in The Cross and the Dragon, and it was worth only a mention in that book. The reason I need to know more now is that the heroine of my work-in-progress, Queen Fastrada, is responsible for schlepping around three little girls, two of them her daughters, the other her husband’s child by a concubine. That’s in addition to children from wives No. 1 and 3, but those kids are riding horses by now.

If you have any idea of what a portable cradle was like, let me know. Otherwise, I might just have to make it up.

July 5, 2013

Did Atom Theory Play a Role in Galileo’s Trouble with the Inquisition?

It’s the first Friday of the month, time for another post on the history of atom theory by physics professor (and my dad) Dean Zollman. Today, we’ll explore whether atom theory contributed to Galileo’s problems with the Inquisition. – Kim

By Dean Zollman

Much has been written about Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) – both scholarly work and historical fiction. One of my favorite fictional accounts is the play Life of Galileo by Bertolt Brecht. When I was the head of a physics department I kept the following quote on my web page.

Much has been written about Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) – both scholarly work and historical fiction. One of my favorite fictional accounts is the play Life of Galileo by Bertolt Brecht. When I was the head of a physics department I kept the following quote on my web page.

“PROCURATOR (speaking to Galileo): I have come in connection with your application for a rise in salary to 1000 scudi. I regret that I cannot recommend it to the university. As you know, courses in mathematics do not attract new students. Mathematics, so to speak, is an unproductive art. Not that our Republic doesn’t esteem it most highly. It may not be so essential as philosophy or so useful as theology, but it nonetheless offers infinite pleasures to its adepts.” (Translated by John Willett)

1636 portrait of Galileo Galilei by Justus Sustermans

Such a conversation between Galileo and his “boss” probably never occurred, but Brecht, writing in the 20th century, created it to point out how the sciences and philosophy have somewhat changed positions in terms of the priorities of society. And of course, Galileo, who incorporated mathematics into science, was one of the people responsible for science becoming as important as it is.

While Galileo is most known for his contributions to understanding the motion of objects and for his use of the telescope to view the heavens, he did also think seriously about the nature of matter. As early as 1612 in his Discourse of Floating Bodies, Galileo used atomistic ideas to explain his observations. More famously, in his Assayer (1623) he discussed the differences between properties that are inherent in an object such as weight and those that are in our mind like taste. In doing so, he uses terms such as “minimal particles” (“particella minima”) to describe the constituents of matter.

This stance put Galileo at odds with the Catholic Church. As I mentioned in a previous post about early clashes between religion and science over atoms, the Eucharist and atoms were seen as incompatible. So, the Church had difficulties with Galileo making statements about matter being made of something like atoms. Galileo, a strong Christian, had a simple solution. The Eucharist was different; concept of atoms applied to everything but it.

Galileo Facing the Roman Inquisition, 1857 painting by Cristiano Banti

However, this statement did not end Galileo’s conflict with the Church. He was also a strong supporter of a heliocentric model of the solar system. His observations through telescopes convinced him that Copernicus was right – the earth and other planets were in orbit around the Sun. For this statement, Galileo had no simple way out of conflict with the Church. In 1633, Galileo was put on trial and convicted “holding as true the false doctrine taught by some that the Sun is the center of the world.” He was sentenced to prison, but that sentence was quickly commuted to house arrest. He remained under house arrest for the rest of his life.

But was Galileo really convicted because of his statements about the solar system? One historian, Pietro Redondi, thinks that the bringing charges about the solar system was a front. Redondi hypothesizes that the real reason the Church wanted Galileo out of the way was his belief in atoms.

Redondi started to build his case based on a discovery that he made in 1982. An anonymous letter written to the tribunal of the Holy See in 1633 denounces Galileo as a heretic because of his views on the nature of matter. It states “He [Galileo] begins by explaining the [properties of matter] with the help of the atoms of Anaxagoras or Democritus, which he calls … minimal particles.” Based on this letter, Redondi speculates that the real reason for the trial was Galileo’s statements about atoms.

However, Galileo’s supporters were concerned that because atoms were seen as opposing the Eucharist, he could have been condemned to death if found guilty. To save his life, Redondi claims, the charges were focused on the solar system.

Redondi has written a book, Galileo Heretic, which makes the case much more completely than I have here. However, I have not found any other historian who considers Redondi’s argument a solid one. Stephen Greenblatt, whom I discussed in an earlier post about rediscovering Roman poet Lucretius, states bluntly that the anonymous letter “did not lead to any action against Galileo.” Bernard Pulllman, who wrote extensively on the history of the atoms, says “I am personally inclined to dismiss [Redondi's hypothesis].” On the other hand, none of us were there, and even if we were, we would not have been party to the secrets of the Inquisition.

(Just for the record, Galileo was eventually exonerated by the Church – in 1992. Sometimes things move slowly.)

Next time, we will move across the English Channel and take a look at how atoms were doing there in the 17th century.

Public domain images from Wikimedia Commons.

Previously:

What Are Things Made of? Depends on When You Ask.

Ancient Greeks Were the First to Hypothesize Atoms

Religion, Science Clashed over Atoms

Medieval Arabic Scholarship Might Have Preserved Scientific Knowledge

Rediscovering a Roman Poet – and Atom Theory – Centuries Later

Reconciling Atom Theory with Religion

Dean Zollman is university distinguished professor of physics at Kansas State University where he has been a faculty member for more than 40 years. During his career he has received three major awards—the National Science Foundation Director’s Award for Distinguished Teacher Scholars (2004), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Doctoral University Professor of the Year (1996), and American Association of Physics Teachers’ Robert A. Millikan Medal (1995). His present research concentrates on the teaching and learning of physics and on science teacher preparation.

June 27, 2013

Is He Charlemagne or Karl der Grosse?

When I told a fellow attendee of last weekend’s Historical Novel Society conference that I write novels set in eighth century Francia, he asked an interesting question: is the king Charlemagne or Karl der Grosse? In other words, does the monarch belong to France or Germany, both of which claim him?

My reply: he’s a Frank. And in the 770s, the time period for my novels, he’s merely King Charles.

A coin with Charles’s image from late in his reign (from Wikimedia Commons, permission granted under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License)

At that time, his realm encompassed today’s France and a sizeable chunk of Germany. It also included Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, and Switzerland. To make assigning a modern-day country even more difficult, his court often moved to his villas and palaces throughout the land, including Quierzy, Worms, Herstal, and Nijmegen. His most famous residence was at Aachen, also called Aix-La-Chapelle, a villa expanded into a palace.

So, it would be disingenuous to assign Charles to a country that he would not have recognized.

Charles’s geography was different from ours. He would have seen his own country as Francia, and his neighbors were Brittany to the northwest, Saxony and Frisia to the northeast, Bavaria to the southeast, Avaria further east, Lombardy to the south, and Hispania to the southwest.

Need further proof that Charles saw himself as a Frank, pure and simple? You only need look at what biographer Einhard says about Charles’s choice of clothes: “He wore the national dress of the Franks.”

June 19, 2013

She Was a Martyr’s Trusted Friend

One challenge of writing historical fiction is what, or in this case whom, to leave out, no matter how interesting. Such is the case with Saint Lioba, featured today on English Historical Fiction Authors.

An altar to St. Lioba at St. Martin in Tauberbischofsheim (photo by Schorle, Wikimedia Commons, permission granted under the terms of GNU Free Documentation License)

A learned woman, the British-born Lioba served as an abbess in Francia, installed by her kinsman Saint Boniface, who needed someone he could trust in his mission to strengthen Christianity in the region. She considered Boniface like a brother and was close to Hildegard, the young queen of Francia at the time of The Cross and the Dragon and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar.

I had read about Lioba in passing during my research, but it did not occur to me to include her in my novels. In researching the post for EFHA, I found her a woman to be admired – pious, good-natured, rarely without a book in her hands.

So why omit such an interesting woman? There was no place for her in either story.

To have included Lioba would have been a case of an author showing off her research, one of those things that leads the reader to think, if they’re being charitable, “This is interesting, but what does this have to do with the story?”

The nice thing about a blog is I can show off my research, and so I invite you to read about a nun who played a role in solidifying Christianity in medieval Europe.

June 11, 2013

Historical Novel Society Interview: Susan Spann

In the days leading up the 2013 Historical Novel Society conference, HNS is interviewing featured guest and speakers. I am honored to host two interviews this month for one of my favorite organizations, through which I know today’s author, Susan Spann. Susan will speak on the panel, “Writing the HF Mystery.” Here, she talks about her inspiration and soon-to-be-launched novel, Claws of the Cat. – Kim

In the days leading up the 2013 Historical Novel Society conference, HNS is interviewing featured guest and speakers. I am honored to host two interviews this month for one of my favorite organizations, through which I know today’s author, Susan Spann. Susan will speak on the panel, “Writing the HF Mystery.” Here, she talks about her inspiration and soon-to-be-launched novel, Claws of the Cat. – Kim

How do you find the people and topics of your books?

Susan Spann

I was attacked by ninjas, and they forced me to write about them.

In May of 2011, I was standing in front of the bathroom mirror, getting ready for work (I’m a publishing lawyer) when I had the random thought: “Most ninjas commit murders, but Hiro Hattori solves them.”

That idea gave birth to the Shinobi Mysteries, which feature a ninja detective solving murders in 16th century (samurai era) Kyoto.

From there, it was mostly a matter of dreaming up new and interesting ways to kill off my imaginary friends.

For you, what is the line between fiction and fact?

Facts are what I deal with when I can’t make up something better.

I’m kidding. Well, at least partly.

My novels take place in 16th century Kyoto, and I chose that period because I love its history and details. When writing that backdrop, I stay as close to the facts as possible, and I’d rather alter my plot to fit accurate scenery than alter the details for the sake of a story. For example, Japanese houses didn’t really have hallways until the 17th century. Rooms opened directly onto one another, which impacts the way my characters deal with movement through buildings (and, sometimes, listening at doors). Keeping those details accurate is important to me.

However, my protagonists, ninja detective Hiro Hattori and his Portuguese Jesuit sidekick, Father Mateo, are entirely fictitious – which frees me from the need to write within the historically-accurate framework of a person’s life and experiences. They do interact with real historical figures, which both limits and expands the story, but I wanted to work with fictitious protagonist characters to give myself more freedom with my storylines.

Can you tell us about your latest publication?

My debut novel, Claws of the Cat, will be published by Minotaur Books on July 16. It’s the first in the Shinobi Mystery series featuring ninja detective Hiro Hattori and his Jesuit sidekick, Father Mateo.

My debut novel, Claws of the Cat, will be published by Minotaur Books on July 16. It’s the first in the Shinobi Mystery series featuring ninja detective Hiro Hattori and his Jesuit sidekick, Father Mateo.

When a samurai is brutally murdered in a Kyoto teahouse, master ninja Hiro has just three days to find the killer before the dead man’s vengeful son kills both the beautiful geisha accused of the crime and Father Mateo, the Jesuit priest that Hiro has pledged his own life to protect. The investigation plunges Hiro and Father Mateo into the dangerous waters of Kyoto’s floating world, where they quickly learn that everyone from an elusive teahouse owner to the dead man’s dishonored brother has a motive to keep the samurai’s death a mystery.

Basically, you take a ninja, a geisha, a female samurai, a Portuguese weapons dealer, a corpse, and a teahouse owner with something to hide, shake well, and toss in a kitten for good measure – because every ninja detective needs a kitten.

***

For more about Susan, visit her website www.susanspann.com.

June 7, 2013

Historical Novel Society Interview: Gillian Bagwell

In the days leading up the 2013 Historical Novel Society conference, HNS is featuring speakers and special guests. I am honored to host two interviews this month for one of my favorite organizations. Today’s author is Gillian Bagwell, who will speak on three panels, including “The Feisty Heroine Sold into Marriage Who Hates Bear Baiting: Clichés in HF and How to Avoid Them.” Here, she talks about fact vs. fiction, her influences, and her latest release, Venus in Winter. – Kim

In the days leading up the 2013 Historical Novel Society conference, HNS is featuring speakers and special guests. I am honored to host two interviews this month for one of my favorite organizations. Today’s author is Gillian Bagwell, who will speak on three panels, including “The Feisty Heroine Sold into Marriage Who Hates Bear Baiting: Clichés in HF and How to Avoid Them.” Here, she talks about fact vs. fiction, her influences, and her latest release, Venus in Winter. – Kim

For you, what is the line between fiction and fact?

Gillian Bagwell

When I have the facts, I use them, and for me one of the most interesting parts of writing historical fiction is researching my characters and making discoveries about them – both major events and odd little facts – that will help bring their stories to life.

But inevitably, there are gaps in the record about historical figures, especially before they became well known. That was certainly the case with the heroines of all three of my books, Nell Gwynn, Jane Lane, and Bess of Hardwick. In each case, I invented their early lives, based on what I knew, what seemed probable or possible and would make a good story.

Ultimately, we’re writing fiction, and writing a great story is more important than providing facts.

Do you have an anecdote about a reading or fan interaction you’d like to share?

Well, the two readings from The Darling Strumpet for the Saturday Night Sex Scenes at the 2011 and 2012 HNS conferences were pretty sensational. Chris Humphreys suggested we read the scene between Nell Gwynn and the Earl of Rochester as a scene in San Diego, and I was thrilled when Diana Gabaldon agreed to read the narration.

My agent taped it, and it got about a zillion hits on YouTube. I was pretty nervous, and it showed! The scene was such a success that we did it again in London last fall, with Bernard Cornwell taking the part of Rochester. I was much more relaxed and having a good time! Bernard and Diana were both wonderful, and the audience was peeing themselves laughing. The links to both readings are on my website, www.gillianbagwell.com.

I like readings, and I teach workshops and coach individual authors on giving effective readings, combining my years of theatre experience with my love of books.

What are your favorite reads? Favorite movies? Dominating influences?

I grew up around theatre, and started acting in my early teens when both my parents were working in administration for the original Renaissance Faire and Dickens Christmas Fair. Being immersed in living history certainly deepened my fascination with the daily lives of people in past times.

Around that time there were several films and TV shows that I found compelling and which influenced me strongly: Upstairs Downstairs, Zeffirelli’s Rome and Juliet, The Lion in Winter, Anne of the Thousand Days, and Elizabeth R with Glenda Jackson as the queen. (I still think of Glenda Jackson when I think of Elizabeth!) I’ve acted in a lot of Shakespeare and other classical plays, and eventually began directing and producing, founding the Pasadena Shakespeare Company and running it for nine years, which has certainly helped my writing, both in terms of seeing and feeling the sensory aspects of scenes as I’m writing, and by immersing me in period language, which is one of the things I enjoy most about writing historical fiction.

Can you tell us about your latest publication?

Venus in Winter covers the first 40 years of the extremely eventful life of Bess of Hardwick, a Tudor-era lady who was married and widowed four times, becoming more wealthy and powerful with each successive husband. She built Chatsworth and Hardwick Hall, and is the ancestor of many of the noble families of England, including the current queen.

Venus in Winter covers the first 40 years of the extremely eventful life of Bess of Hardwick, a Tudor-era lady who was married and widowed four times, becoming more wealthy and powerful with each successive husband. She built Chatsworth and Hardwick Hall, and is the ancestor of many of the noble families of England, including the current queen.

Bess knew just about anyone who was anyone in the second half of the 16th century and had a close-up view of some fascinating and terrible times. As a young girl, she served in the Grey household, and Jane Grey was like a little sister to her. Later, she was a lady of the privy chamber to Queen Elizabeth. Shortly after her fourth marriage, she and her husband became the keepers of Mary Queen of Scots, an arrangement they expected to be temporary, but which lasted 17 years, contributing to the ruin of their marriage. But that story will have to wait for a second book.

***

Gillian Bagwell’s third novel, Venus in Winter, will be released on July 2, and will be available for early purchase at the HNS conference.

Venus in Winter follows on the success of Gillian’s first two novels, The Darling Strumpet, based on the life of Nell Gwynn, 17th-century actress and mistress of Charles II, and The September Queen, the first fictional account of the extraordinary adventure of Jane Lane, who risked her life to save Charles II and the future of the monarchy after the disastrous Battle of Worcester in 1651.

Please visit Gillian’s website, www.gillianbagwell.com, for links to her research blogs and more on her books and upcoming events.