Jeremy Dean's Blog, page 823

April 24, 2013

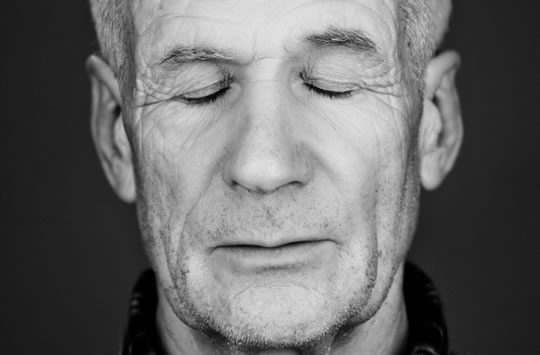

The Peaceful Mind: 5 Step Guide to Feeling Relaxed Fast

We worry about work, money, our health, our partners, children...the list goes on.

And let's face it, there are plenty of things to worry about, and that's even before you've turned on the news. This means that when the mind is given an idle moment, often what it seems to fill it with is worrying.

Worry can be useful if it's aimed at solving problems but less useful when it's just making us unhappy or interfering with our daily lives.

The standard psychological methods for dealing with everyday worry are pretty simple. But just because they're simple and relatively well-known doesn't mean we don't need reminding to use them from time-to-time.

So here is a five-step plan called "The Peaceful Mind" that was actually developed by psychologists specifically for people with dementia (Paukert et al., 2013). Because of this it has a strong focus on the behavioural aspects of relaxation and less on the cognitive. That suits our purposes here as the cognitive stuff (what you are worrying about) can be quite individual, whereas the behavioural things, everyone can do.

1. Awareness

This is the step most people skip. Why? Because it feels like we already know the answer. You probably already think you know what makes you anxious.

But sometimes the situations, physical signs and emotions that accompany anxiety aren't as obvious as you might think. So try keeping a kind of 'anxiety journal', whether real or virtual. When do you feel anxious and what are the physical signs of anxiety?

Sometimes this stage on its own is enough to help people with their anxiety. As I never tire of saying, especially in the area of habits, self-awareness is the first step to change.

2. Breathing

If you've been reading PsyBlog for a while you'll know all about how both mind and body each feed back to the other. For example, standing confidently makes people feel more confident. Mind doesn't just affect body, body also affects mind.

It's the same with anxiety: taking conscious control of breathing sends a message back to the mind.

So, when you're anxious, which is often accompanied by shallow, quick breathing, try changing it to relaxed breathing, which is usually slower and deeper. You can count slowly while breathing in and out and try putting your hand on your stomach and feeling the breath moving in and out.

In addition, adopt whatever bodily positions you associate with being relaxed (although suddenly lying down before giving a talk in public might be a step too far!). Typically these are things like relaxing muscles, adopting an open stance to the world (unfold arms, hint of a smile).

3. Calming thoughts

It's all very well saying: "Think calming thoughts", but who can think of any calming thoughts when stressful situations are approaching and the heart is pumping?

The key is to get your calming thoughts ready in advance. They could be as simple as "Calm down!" but they need to be things that you personally believe in for them to be most effective. It's about finding what form of words or thoughts is right for you.

4. Increase activity

It might seem strange to say that the answer to anxiety is more activities, as we tend to think the answer to anxiety is relaxation and that involves doing less.

But, when unoccupied, the mind wanders, often to anxieties; whereas when engaged with an activity we enjoy, we feel better. Even neutral or somewhat wearing activities, like household admin, can be better than sitting around worrying.

The problem with feeling anxious is that it makes you less likely to want to engage with distracting activities. You see the problem.

One answer is to have a list of activities that you find enjoyable ready in advance. When anxiety hits at an inactive moment, you can go off and do something to occupy your mind.

Try to have things on your list that you know you will enjoy and are easy to get started on. For example, 'invent a time machine' may be biting off a tiny bit more than you can chew, but 'a walk around the block' is do-able.

5. Sleep skills

Often when people are anxious they have problems sleeping. Sometimes when you feel anxious there's nothing worse than lying in bed, in the dark, with only your own thoughts to occupy your attention.

And lack of sleep leads to anxiety about sleeping which can lead, paradoxically, to worse sleep.

Breaking out of this loop can be hard but practising 'sleep hygiene' can help. This is all about getting into good sleeping habits. I've covered this before in 6 Easy Steps to Falling Asleep Fast, so check that article out for the details.

Image credit: Several seconds

Did you know that every post on PsyBlog is written by a British psychologist called Jeremy Dean?

Did you know that he has a new book out called "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", now available on Amazon?

You did? Well, carry on then...

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

April 15, 2013

Can Everyday Hassles Make You Depressed?

When it comes to pinpointing the source of our woes, we tend not to think too much about the little hassles of everyday life; after all they're just little hassles, nothing compared to the big stuff.

You're late for a meeting, you run out of biscuits or you get a parking ticket; irritating certainly, but nothing really serious, or anything like it.

Instead, we tend to blame the big events in life: divorce, disease and bereavement. And, when looking for what puts people over the edge, that's exactly where psychological researchers have concentrated their attention: on the big stuff.

But many are waking up to the fact that although the little hassles in life are smaller, they're also more numerous, so they can really add up over time. And, whether stressful events are big or small, it matters a lot how we deal with them.

Daily stressors

In new research published in Psychological Science, Charles et al. (2013) looked at people's reactions to everyday stressors and how this played out a decade later. Participants were asked about their daily stressors over eight days and generally how they felt. People reported having all the usual sorts of stressors like having arguments, a fridge breaking down or being late for an appointment.

Then, 10 years later, they were revisited and asked whether they had been treated for anxiety, depression or any other emotional problems in the last year.

What the results showed was that how people reacted to the little stressors of everyday life predicted whether they developed psychological problems a decade later (incidentally, the number who did report a disorder was almost one in five).

This fits in with other recent studies which have also shown that people's reactions to ordinary stressors predict depressive symptoms (e.g. Parrish et al., 2011).

Whether problems are big or small, what matters is how we react to them. People who tend to do worst are those that have the strongest emotional reaction to both big and small events.

We tend to think that depression is always a reaction to some really bad thing happening and sometimes it is; but sometimes it's all those little things piled on top of one another that can get you down.

Image credit: Stephen Poff

Did you know that every post on PsyBlog is written by a British psychologist called Jeremy Dean?

Did you know that he has a new book out called "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", now available on Amazon?

You did? Well, carry on then...

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

April 9, 2013

Are Men or Women Better at Multitasking?

First a confession: I have never understood the popular fascination with whether women (or men) are better at multitasking.

That's because multitasking is something that's best avoided for any task that needs concentration. Humans don't multitask well, unless one of the activities is automatic and doesn't require much (conscious) processing.

Still, one of the reasons the question keeps coming back is because of the media obsession with the battle of the sexes; they like to report anything that shows even the most minuscule psychological gender differences.

As a result what we get is the news that, one week, women are better at multitasking and the next week it's men.

Part of the reason you see these articles is that some studies do indeed find a small superiority for women and some find a small superiority for men, depending on the exact tasks.

But let's take a real-world activity like driving. What if you compare how good men and women are at driving while talking on a mobile phone? Now, somewhere at the back of your mind, perhaps, there may be prejudices brewing.

Stifle those thoughts, though, because Watson and Strayer (2010) have found no difference between men and women on this sort of multitasking.

And it turns out that this is the case in general for multitasking. Overall studies struggle to find strong, consistent evidence one way or the other (Strayer et al., 2013).

Certainly, some people, both men and women, are better multitaskers than others, and that is interesting. But as for the difference between men and women, the truth is there is much more variation amongst men and women than there is between men and women.

As ever with a young science like psychology, the balance of evidence may change in the future, but at the moment the best guess is that the differences are very small or non-existent.

So the next time someone makes a comment about gender differences in multitasking, you can say: "Rubbish, I read on PsyBlog that there are no proven differences between men and women at multitasking."

Image credit: Rodrigo Sombra

Did you know that every post on PsyBlog is written by a British psychologist called Jeremy Dean?

Did you know that he has a new book out called "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", now available on Amazon?

You did? Well, carry on then...

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

April 3, 2013

Rethinking The Stress Mindset: Can You Find The Upside of Pressure?

It's striking how much of our emotional experience is down to interpretation.

Take the physical feelings you get when you're about to talk in public: the sweaty palms, the churning stomach and the spinning room. Isn't that much the same physical experience you get when you've fallen in love?

Yet one experience most would run a mile from and the other we enjoy. The difference is partly down to the meaning we give these events.

But how far does this go? What about the hassles of everyday life and stress in general? Is stress really a killer or can it be reinterpreted away?

Well, there's certainly such a thing as the way that we habitually think about stress. One of the most common, which is frequently reinforced by the media, is the 'stress-is-debilitating' mindset.

What Crum et al. (2013) wonder in a new paper is: can we change this mindset and does thinking about stress in a positive way have any effect on how we react to it?

To conduct some preliminary tests, they recruited a group of investment bankers, who were split into three groups, each of which were shown a different 10-minute video. Some of them watched a video that suggested stress can be good for you.

The 'stress-is-enhancing' video suggested that some people do their best work under pressure: for example, Captain "Sully" Sullenberger landed his stricken airliner on the Hudson River and Winston Churchill successfully led Britain through WWII.

A second group watched a video reinforcing the idea that stress is debilitating, while a third acted as a control.

The bankers reported back over a few weeks on their stress mindset, how they were doing at work and their levels of stress. The results showed that those who'd seen the 'stress-is-enhancing' video did develop a more positive stress mindset. This led to them reporting better performance at work and fewer psychological problems over the subsequent two weeks.

This suggests something as simple as a short video can start to change how you think about stress, at least in the short-term.

Another study by Crum et al. examined one possible mechanism for how a changed mindset might be beneficial. This found that people who tended to think stress was enhancing were more likely to want feedback. So, people who think positively about stress are likely to use that to help them solve problems.

In addition, thinking that stress is enhancing was associated with lower levels of cortisol, a hormone closely associated with the stress response. In other words, people's physiological reaction to stress was better when they endorsed the idea that stress is enhancing.

So, is stress good or bad for you? This evidence underlines the fact that, as so often, what you believe influences how both mind and body reacts.

Image credit: Truthout.org

Did you know that every post on PsyBlog is written by a British psychologist called Jeremy Dean?

Did you know that he has a new book out called "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", now available on Amazon?

You did? Well, carry on then...

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

March 20, 2013

The Temporal Doppler Effect: Why The Future Feels Closer Than The Past

Sometimes psychologists come up with such good names for their findings that I'm powerless to resist. Take this newly minted expression: 'the temporal Doppler effect'.

This really appeals to both the psychologists in me and my inner physics geek.

Here's a reminder of the Doppler effect, which I'm sure you've experienced even if you haven't heard of the Austrian physicist Christian Doppler (click here for YouTube video):

(In case you can't see the video: the Doppler effect is most often experienced when an ambulance with siren blaring travels past you. The pitch of the siren shifts downwards as it whizzes past. The siren's notes aren't actually changing in pitch; it's the effect of the ambulance's movement on the sound-waves reaching your ear that produces the effect.)

So, what is a temporal Doppler effect and what does this have to do with psychology?

It seems to suggest that as events approach us from the future they feel closer, compared with events in the past, which feel further away as they recede. In other words: one week in the future feels closer in time than one week in the past.

How far away does it feel?

Could that be true? For example, imagine I ask you one week before Valentine's Day how psychologically distant that feels to you. Then, imagine I ask you the same question one week after Valentine's Day. Surely they should feel about the same distance?

What the temporal Doppler effect suggests is that Valentine's Day will feel closer in time one week beforehand than one week after.

Sounds mad? Well this is exactly the experiment that Caruso et al. (2013) carried out. And guess what? They got this temporal Doppler effect. On a 1 to 7 scale, where 1 means it feels close in time and 7 means it feels far in time, people rated an upcoming Valentine's Day an average of 3.9 when it was one week in the future, but an average of 4.8 when it was one week in the past.

They got similar results for comparisons of time-points both one month and one year in the future and the past. This temporal Doppler effect kept showing up: the future seems to feel psychologically closer to people than the past, despite the fact we know it's exactly the same.

Metaphors of time and space

So why does it happen? Caruso et al. put forward two explanations, one more abstract than the other. I'll do the abstract one first but feel free to bail out and get on to the concrete one if it gets too much!

The abstract argument goes like this: we don't directly experience time although we see its effects. Unlike space, which we can clearly see, time is invisible. In contrast, you can reach out and touch objects and feel the space between them.

Because time is abstract we try to understand it psychologically using metaphors. We say that 'time flows like a river', 'time marches on' or 'time flies'. These are all spatial ways of thinking about an abstract idea.

The result is that we unconsciously apply the same spatial rules to time. Just like things that are coming towards us sound higher in pitch and appear to us closer in space than things going away, so we intuit that things ahead of us in time are also closer than things in the past.

Convinced?

If not you'll be interested in a further experiment Caruso et al. carried out where they tried to reverse the temporal Doppler effect with a simple manipulation: they had people walking backwards in virtual reality (VR).

Compared to those walking forwards in VR, those walking backwards showed no tendency towards thinking the future was closer than the past. This helps support the idea that how we think about time is linked to how we think about space and why the temporal Doppler effect occurs.

Future-facing

Now here's the more concrete explanation. The temporal Doppler effect is also highly adaptive. It's very useful for our survival and success in life that the future seems closer than the past. What happens tomorrow we can plan for, what happened yesterday is just a memory.

Yes, it's important to understand where you've come from, but without a plan, you can't know where you're going. The temporal Doppler effect is one example of how we're future-oriented creatures; always scheming for, worrying about, plotting and simulating the future. So that hopefully, when we get there, we've got some kind of plan.

Image credit: Myxi

Did you know that every post on PsyBlog is written by a British psychologist called Jeremy Dean?

Did you know that he has a new book out called "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", now available on Amazon?

You did? Well, carry on then...

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

→ Latest Novel by Psychologist David Liebert--A Psychological Gritty Tale of Socipathic Lust and Revenge.

March 12, 2013

The Endowment Effect: Why It’s Easy to Overvalue Your Stuff

No matter what it is—a pair of jeans, a car or even a house—in that moment when an object becomes your property, it undergoes a transformation.

Because you chose it and you associate it with yourself, its value is immediately increased (Morewedge et al., 2009). If someone offers to buy it from you, the chances are you want to charge much more than they are prepared to pay.

That is a cognitive bias called 'the endowment effect'.

It's the reason that some people have lofts, garages and storage spaces full of junk with which they cannot bear to be parted. Once you own something, you tend to set its financial value way higher than other people do.

When tested experimentally the endowment effect can be surprisingly strong. One study found that owners of tickets for a basketball match overvalued them by a factor of 14 (Carmon & Ariely, 2000). In other words people wanted 14 times more than others were prepared to pay. However, this is a particularly high one and the ratio will vary depending on what it is.

The endowment effect is particularly strong for things that are very personal and easy to associate with the self, like a piece of jewellery from your partner. Similarly we also overvalue things we've had for a long time.

Sometimes, of course, the sentimental value of things is justified; but more often than not people hold on to old possessions for no good reason. So if you're surrounded by rubbish, ask yourself: do I really need all this, or is it the endowment effect?

After all, it's just stuff.

Image credit: Kevin Utting

Did you know that every post on PsyBlog is written by a British psychologist called Jeremy Dean?

Did you know that he has a new book out called "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", now available on Amazon?

You did? Well, carry on then...

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

→ Latest Novel by Psychologist David Liebert--A Psychological Gritty Tale of Socipathic Lust and Revenge.

March 11, 2013

“Is the Internet Good/Bad For You?” and Other Dumb Questions

Over the last few years we've been bombarded by articles and books about Facebook, social media and the Internet in general. The slant of these tends to go one of three ways (and for each one 'Facebook' is interchangeable with 'Twitter', 'the Internet' or whatever):

Facebook is great! We're all connected to each other so it's easier to get a new job, find old friends, create amazing stuff together and live happily ever after.

Facebook is horrible! It's filled with stalking; it generates jealously, loneliness and destroys our real relationships with each other.

Facebook's effects are mixed: some research says it's good for you, some says it's bad for you.

Unfortunately all these approaches are based on a bad assumption; even the third one (although it gets closest to the truth). The problem is that they're all a bit like asking: is life good for you? The question is crass.

The effects of Facebook, the same as for all social media, the Internet in general, and even life itself will depend on exactly what you do with it.

Consider Facebook for a moment. There are all kinds of things you can do: stalk old partners, play games, find fascinating content, keep in touch with old friends or look at random pictures of other people's drunken nights out (not all of these are recommendations).

People's creativity in using online services streaks way ahead of our knowledge of what it means and how it affects us. In fact we're only just starting to see studies that make more fine-grained distinctions about what people are actually doing online and how that may, or may not, be good for them.

A recent example made a telling distinction between active and passive Facebook use (Burke et al., 2010). Passive Facebook use includes scrolling through other people's photos and reading their updates while active use includes updating your status and writing private messages. Perhaps you'll be unsurprised to learn that the active kind is the good one for increasing social bonding.

Although this is a relatively crude distinction, at least it's starting to look at how people are using social media like Facebook, not just how much.

In a similar vein, there's a new study looking at Facebook use and loneliness. It examines the old question about whether being online makes us lonely which, I've discussed along with other bugbears here.

Instead of doing a survey, though, they carried out an experiment (Deters & Mehl, 2012). They wanted to know if Facebook status updating could cause you to feel less lonely. Long story (as it must be nowadays) short; in the group they studied, it did.

When participants made more Facebook updates, they felt less lonely and this was caused by feeling more connected to their friends on a daily basis. Surprisingly it didn't depend on whether their friends replied or not, or how they replied, just reaching out had the effect of reducing loneliness.

Now this won't be the end of the argument about whether Facebook or the Internet in general is good for us, but it's a great start and at least it asks the right questions. It looks experimentally at a specific aspect of Facebook usage, status updating, to look at the effects on loneliness.

If anything, the study reiterates something we know from our everyday, offline lives. If you see a friend in the street it's better to say hi and ask how they are than passively observe them from a distance. But it's good to know that this simple intuition is confirmed in an online environment.

More broadly, it's the type of study that's looking a bit deeper into what social media and the Internet are doing to us by breaking the question down. It's an encouraging sign.

We may not yet be able to say that much about what aspects of Internet use are psychologically good or bad for us, but at least we're starting to ask the right questions.

Image credit: Viktor Hertz

Did you know that every post on PsyBlog is written by a British psychologist called Jeremy Dean?

Did you know that he has a new book out called "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", now available on Amazon?

You did? Well, carry on then...

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

→ Latest Novel by Psychologist David Liebert--A Psychological Gritty Tale of Socipathic Lust and Revenge.

March 5, 2013

Mental Practice Makes Perfect

If you were to undergo brain surgery, would you care if the surgeon regularly carried out mental practice of the operation? Or, would you only be interested in the physical practice?

(By mental practice I don't mean getting 'psyched up' or making plans or getting in the right frame of mind; I mean mentally running through the physical movements required for the operation.)

Quite naturally you'd probably be much more interested in how often the surgeon had carried out the operation in real life, rather than in his imagination.

But should you be? What is the value of mental practice, not just in surgery, but in life in general? How much benefit is there to mental rehearsal and do we undervalue the power of mental practice?

Rehearsal

For neurosurgery specifically there is no study looking at what difference mental practice can make (although some surgeons do carry out this sort of rehearsal). But we do know that for basic surgical techniques, mental practice can benefit performance.

One study by Sanders et al. (2008) was carried out on medical students. On top of their usual training—which included physical practice—half were trained in mental imagery techniques, while the other half studied their textbooks.

When the students carried out live surgery, those who'd used mental imagery performed better, on average, than those assigned the book learning.

Another study looking at laparoscopic surgery has also shown benefits for mental practice for novice surgeons (Arora et al., 2011).

Away from the operating theatre, the main way we're used to hearing about mental rehearsal is in sports. Whether it's an amateur tennis player or Roger Federer, sports-people often talk about how mental rehearsal improves their performance.

My favourite example is the British Formula 1 driver, Jenson Button. In practice he sits on an inflatable gym ball, with a steering wheel in his hands, shuts his eyes, and drives a lap of the circuit, all the while tapping out the gear changes. He does this in close to real time so that when he opens his eyes he's not far off his actual lap time.

Powerful pinkies

The reason that sports-people, surgeons and many others are interested in the benefits of mental practice is that they can be so dramatic, plus they are effectively free.

Here's a great example from a simple study in which some participants trained up a muscle in their little fingers using just the power of mental practice (Ranganathan et al., 2004). In the study participants were split into four groups:

These people performed 'mental contractions' of their little finger. In other words, they imagined exercising their pinkies.

Same as (1), but they performed mental contractions on their elbows, not their little fingers.

Did no training at all.

Carried out physical training on their little finger.

They all practised (or not) in the various different ways for four weeks. Afterwards, the muscle strength in their fingers and elbows was tested. Unsurprisingly those who'd done nothing hadn't improved, while those who'd trained physically improved their muscle strength by an average of 53%.

The two mental practice groups couldn't beat physical training, but they still did surprisingly well. Those imagining flexing their elbow increased their strength by 13.5% and those imagining flexing their little finger increased their strength by 35%. That's surprisingly close to the 53% from physical training; I bet you wouldn't have expected it to be that close.

Thinking practice

This is just strength training, but as we've seen there's evidence that mental rehearsal of skills also produces benefits. Examples include mentally practising a music instrument, during rehabilitation from brain injuries and so on; the studies are starting to mount up.

Indeed some of these have shown that mental practice seems to work best for tasks that involve cognitive elements, in other words that aren't just about physical actions (Driskell et al., 1994).

So it's about more than mentally rehearsing your cross-court forehand. Rehearsal could also be useful for a job interview or important meeting; not just in what you'll say but how you'll talk, carry yourself and interact with others. Mental rehearsal could also be useful in how you deal with your children, or make a difficult phone call or how you'll accomplish the most challenging parts of your job.

Notice the type of mental imagery I'm talking about here. It's not so much about visualising ultimate success, with all its attendant pitfalls, but about visualising the process. What works is thinking through the steps that are involved and, with motor skills, the exact actions that you will perform.

To be effective, though, mental practice has to be like real practice: it should be systematic and as close to reality as you can make it. Just daydreaming won't work. So if you make a mistake, you should work out why and mentally correct it. You should also make the practice as vivid as possible by tuning in to the sensory experience: what you can see, hear, feel and even smell, whatever is important.

If it can work for surgeons, elite athletes and little-finger-muscle-builders, then it can work for all of us.

Image credit: Adam Rhoades

Did you know that every post on PsyBlog is written by a British psychologist called Jeremy Dean?

Did you know that he has a new book out called "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", now available on Amazon?

You did? Well, carry on then...

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

→ Latest Novel by Psychologist David Liebert--A Psychological Gritty Tale of Socipathic Lust and Revenge.

February 28, 2013

Twitter: 7 Highly Effective Habits

If you want more Twitter followers, new research provides some easy pointers to the right type of tweeting.

This is the first study to examine what factors are associated with an increased follower-count on Twitter over an extended period of time. Hutto et al. (2013) studied 507 Twitter users over 15 months and half-a-million tweets (PDF).

Some of these are just handy reminders of good Twitter practice, but you may find the odd surprise—see what you think.

1. Avoid negative sentiments

If you're quite a negative Tweeter, then it could be time to change, if you care about getting more followers. In general people are attracted to those who put out broadly positive tweets.

It seems that negative or sarcastic tweets are not endearing. In this study, being consistently negative was one of the strongest predictors of low follower growth. The average ratio was two positive tweets to one negative, so you'd be looking to beat this to help draw in other users.

2. Inform, don't meform

This one is so important for gaining new followers. A previous study has shown that there are broadly two types of Twitter users (Naaman, 2010):

Informers: 20% share information and reply to other users

Meformers: 80% mostly send out information about themselves.

This study found that it's the informers who get more followers, while the meformers lose out.

Being informative was one of the strongest predictors of gaining new followers in this study: this included passing on links and retweeting. In fact being an informer rather than a meformer was associated with 30 times more growth in followers!

3. Boost social proof/trust

Not only should you produce informative tweets, but they should be the kind that are retweet-worthy. Being retweeted is a sign to others that you are worth following. Unfortunately there weren't any further clues in this research on what makes a tweet retweet-worth.

However one easy way you can boost social trust is by completing your user profile. Those who gave a web address, a location and a long description were more likely to attract followers in this sample. This has also been found amongst Facebook users, where more complete profiles attract more friends.

4. Stay on topic

Many Twitter users tweet about all kinds of subjects, perhaps thinking that a broader focus will attract more users. Celebrities, in particular, can afford to talk about what they like because it's them we are interested in. But if you're not a celebrity, then a scatter-gun approach to tweeting may not be so effective.

In general, people want to find others who share their interests and are like them. This is just as true on Twitter as it is in face-to-face relationships. This study found that people who remained more 'on-topic' tended to attract more followers.

Why? Well, it may be a signal-to-noise-type thing. If you stay on-topic, your interests are clearer and it's easier to make the choice to follow you.

5. Write well and avoid hashtag abuse

Everyone who cares about good writing will be glad to see this one come up. Apparently people really do seek out well-written content, even if it's only 140 characters or less.

The usual approach online, beyond correct spelling, is to pitch your writing at a reasonably intelligent 12-year-old. But in this study some moderate complexity was associated with increased followers, so don't be afraid of the odd long word.

While we're talking about writing well, another Twitter faux pas is the overuse of hashtags. In this sample it was associated with a reduced number of followers. People seem to hate the #random #use #of #hashtags.

6. Be bursty

There's nothing wrong with having a burst of Twitter activity, say 10 messages in an hour. Twitter users who were bursty from time-to-time tended to attract more followers.

7. Switch from broadcast to direct tweets

Do you direct your tweets to particular people or are they just general broadcasts to the world?

It's usually a balance between the two and in this study the average split was about 45% broadcast to 55% targeted.

In this sample, though, it paid in terms of more followers to increase the proportion of directed tweets and decrease the broadcasts. Naturally people usually like it when you talk to them directly.

***

• Do remember that this study is correlational so we can't tell that these factors are causing the increased follower counts, but because the data were collected over 15 months, it is a good indication of what works.

• For more in-depth research on Twitter, check out: Twitter: 10 Psychological Insights. And for companion Facebook info, see Facebook: 7 Highly Effective Habits.

• And (here comes the inevitable!) you can follow me @PsyBlog.

Image credit: mkhmarketing

Did you know that every post on PsyBlog is written by a British psychologist called Jeremy Dean?

Did you know that he has a new book out called "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", now available on Amazon?

You did? Well, carry on then...

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

→ Latest Novel by Psychologist David Liebert--A Psychological Gritty Tale of Socipathic Lust and Revenge.

February 27, 2013

The Surprising Power of an Emotional ‘Memory Palace’

"I'm going to my happy place!"

Saying this in moments of stress has become a rather tired joke. And the joke conceals the fact that having a so-called 'happy place', or even several happy places can help boost mood when times are hard.

However, the problem with thinking back to happy moments from the past is that it's hard if you're not in the habit.

Indeed people experiencing depression find it particularly difficult. Worse, when they do recall happier times, they tend to do it abstractly, focusing on the causes, meaning and consequences, and looking for clues as to how to regain it. Unfortunately it's re-experiencing the pleasure that gives you the boost in the moment, not thinking about it abstractly.

The problem is frequently memory. To feel better by thinking back to past glories, you've got to pull up the right memories and in the requisite detail. This can be hard enough for the most equable of souls and nearly impossible when low mood strikes.

What is required is a really strong technique for instantly conjuring up the right moments from the past so that you feel right there, in the moment.

Method-of-loci

The 'method-of-loci' technique (literally method-of-places) for enhancing memory has been around for thousands of years. It was recommended by the Roman philosopher Cicero and in 2006 was used by Lu Chao to recall π to 67,890 places (he recited it for 24 hours and 4 minutes before he made a mistake).

But you don't have to be a specialist memoriser or super-brain to find the technique useful; it has dramatic effects on recall for even the most humble of us.

The method-of-loci technique, which relies on spatial memory, is remarkably simple to explain, but does require some mental effort to set up. What you do is think of a place that you know really well, like a house you lived in as a child or your route to work. Then you place all the things you want to remember around the house as you mentally move around it. Each stop on the journey should have one object relating to a memory. The more bizarre and surreal or vivid you can make these images, the better they will be remembered.

If you carried out this process for a series of good memories, you'd have what is called a 'memory palace' of happy times that you could return to in moments of stress.

Building a memory palace

As ever here on PsyBlog, though, we want to know if it really works. Can creating a memory palace be effective even for depressed people: those who find it particularly difficult to remember happy times?

That's what was tested in a new study by Dalgleish et al. (2013) who recruited 42 participants who were currently experiencing a major depressive disorder or who had suffered in the past and were now in remission.

Half the participants were taught the method-of-loci technique. Here's an example of how one person encoded a memory to give you the flavour:

"...one participant in the main study had generated a memory of an important conversation over coffee in New York with her best friend. She associated the memory with the front of her childhood home (one of her selected loci) by imagining the fascia of the house transformed into an outlet of a popular U.S. coffee chain with her friend standing outside smiling and dressed as a barista."

Everyone rehearsed 15 of these self-affirming memories and placed them around their memory palaces. They then practised going around their individual mental routes until they could easily retrieve the memories and the associated feelings in high levels of detail.

The rest of the participants also recalled 15 positive events but used a memory technique that you'll be more familiar with from school. They simply rehearsed them over-and-over again until it seemed to have gone in.

Unsurprisingly both groups reported that remembering happy past memories made them feel better.

But the key for the researchers was to see whether people could still recall the memories one week later, in a surprise telephone call. The results showed that the participants who had rehearsed the memories repeatedly had forgotten, on average, two of them. In contrast, the average barely dropped for those who had used the method-of-loci.

This is an encouraging result and suggests that the method-of-loci is an effective way to easily recall a set of happier times, even in people who find it difficult to do so.

OK, enough theory, I'm off to create my emotional memory palace right now and spend a little time wandering the halls and enjoying myself.

Perhaps you might like to try it yourself?

Image credit: Manuela de Pretis

About 50% of our everyday lives is habitual. While we're awake, then, about half the time we are repeating the same actions or thoughts in the same contexts. Automatically. Without thinking. It's part of the reason change is so hard.

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits', gives you a blueprint for how to create new habits and tackle bad ones, whatever they are, and how to make it automatic so that willpower is no longer an issue.

→ You can dip into the first chapter, or check it out on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

→ Latest Novel by Psychologist David Liebert--A Psychological Gritty Tale of Socipathic Lust and Revenge.

Jeremy Dean's Blog

- Jeremy Dean's profile

- 29 followers