Jeremy Dean's Blog, page 822

May 30, 2013

How Our Emotions Work: 10 Psychological Insights

Emotions aren't just things that happen to us, they are vital components of how we reason, motivate ourselves, think about the past and future and how we communicate with others.

Our emotional selves are sometimes remarkably resilient, sometimes out of control and often difficult to understand. Good feelings inevitably fade, while negative ones can stay with us forever.

To help explore your emotional side, here is my top 10 pick of articles from PsyBlog on the psychology of emotions:

Does Keeping Busy Make Us Happy? - People dread being bored and will do almost anything to keep busy, but does keeping busy really make us happy?

The Upside of Anger: 6 Psychological Benefits of Getting Mad - We tend to think of anger as a wild, negative emotion, but research finds that anger also has its positive side.

12 Laws of the Emotions - Emotions follow their own rules, like that of situational meaning, habituation, closure and concern.

The Psychological Immune System - We get over bad moods much sooner than we predict, thanks to the covert work of the psychological immune system.

What “The Love Bridge” Tells Us About How Thoughts and Emotions Interact - How much control do you have over your emotions?

The Power of Regret to Shape Our Future - Why people are reluctant to exchange lottery tickets, but will happily exchange pens.

4 Ways Benign Envy is Good For You - Feeling green with envy? If it's the right type of envy, maybe it's no bad thing...

Duchenne: Key to a Genuine Smile? - Experiments cast doubt on the classic marker of a genuine smile.

The Surprising Power of an Emotional ‘Memory Palace’ - Can a 'memory palace' help you recall happier times, even when life is hard?

4 Life-Savouring Strategies: Which Ones Work Best? - We can increase our positive emotions and life satisfaction by using the right mix of savouring strategies.

Image credit: Alvaro Tapia

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

In his new book, Jeremy Dean--psychologist and author of PsyBlog--looks at how habits work, why they are so hard to change, and how to break bad old cycles and develop new healthy, creative, happy habits.

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

Reviews

The Bookseller, “Editor’s Pick,” 10/12/12

“Sensible and very readable…By far the most useful of this month’s New You offerings.”

Kirkus Reviews, 1/1/13

“Making changes does take longer than we may expect—no 30-day, 30-pounds-lighter quick fix—but by following the guidelines laid out by Dean, readers have a decent chance at establishing fulfilling, new patterns.”

Publishers Weekly, 12/10/12

“An accessible and informative guide for readers to take control of their lives.”

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

May 29, 2013

What Might Have Been: The Benefits of Counter-Factual Thinking

One of the mind's great talents is to simulate events that haven't happened. Projected into the future, our imaginative power helps us plan everything from our weekends to the construction of our homes and cities.

But when our minds turn towards the past, our ability to simulate alternative realities seems less useful. What use is it to imagine how things could have been? Do we not learn more from our pasts by analysing the reasons for either success or failure?

A recent study by Kray et al. (2010), though, demonstrates a role for thinking about what might have been that doesn't invoke that horrible word: regret.

Instead they wonder if thinking about what might have been actually helps us make more sense of our lives.

In the first of four studies they had students think about the sequence of events that had led them to attend that particular college. Half the participants then wrote about all the things that could have gone differently. Finally, everyone completed measures of meaning and significance of events in their lives.

The results showed that those who had considered counter-factuals—how their lives might have been different—gave higher ratings to the significance of their choice to attend that particular college and to how meaningful this was in their lives.

Psychologically, then, thinking about how life could have been different, made people feel that what did actually happen was more special in comparison.

In three mores studies they confirmed this finding and looked at what mechanisms connected counter-factual thinking with meaning-making. Two emerged:

Fate. Thinking about what might have been makes us feel that major events in our lives were 'fated'. This is because counter-factuals make you more aware of all the other things that could have happened.

Finding the upside. When people thought about counter-factuals, they noticed more positive aspects to the true chain of events. Many people were even able to find the upside of apparently negative events (things like: "If I hadn't broken my leg, I wouldn't have met my husband").

As Kray et al. conclude:

"Mentally veering off the path of reality, only briefly and imaginatively, forges key connections between what might have been and what was meant to be, thereby injecting our experiences and relationships with deeper meaning and significance."

Image credit: pedro veneroso

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

In his new book, Jeremy Dean--psychologist and author of PsyBlog--looks at how habits work, why they are so hard to change, and how to break bad old cycles and develop new healthy, creative, happy habits.

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

Reviews

The Bookseller, “Editor’s Pick,” 10/12/12

“Sensible and very readable…By far the most useful of this month’s New You offerings.”

Kirkus Reviews, 1/1/13

“Making changes does take longer than we may expect—no 30-day, 30-pounds-lighter quick fix—but by following the guidelines laid out by Dean, readers have a decent chance at establishing fulfilling, new patterns.”

Publishers Weekly, 12/10/12

“An accessible and informative guide for readers to take control of their lives.”

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

May 28, 2013

9 Ways The Mind Resists Persuasion and How To Sustain or Overcome Them

What runs through your mind when someone tries to persuade you?

Say they start telling you about their preferred make of car, the right area to live in or why you should vote this way or that.

How do you react?

And what if you are actively trying to persuade other people; do you know what is going on in their heads? What internal mechanisms are swinging into action as you start to try and convince them?

Here are the top 9 ways that the mind resists persuasion and how to both break them down or sustain them.

1. Inoculation

Medical inoculations work by giving you a little of the disease so that your body can get used to it and fend off a full attack in the future. Psychological inoculations against persuasion work the same way.

When people have already been prepared with counter-arguments they find it easier to fend of persuasion attempts.

• When persuading: what counter-argument will people already know? Avoid the 'usual' arguments in your persuasion attempt. Instead use a new angle they haven't thought about before.

• When resisting persuasion: expose yourself to different types of arguments and counter-arguments you will likely face. When you know what's coming it's easier to defend yourself psychologically. Look for indirect persuasion attempts: perhaps it's the same old argument made in a slightly different way.

2. Forewarned is forearmed

When we can see the persuasion attempt coming, it's much easier to marshal our defences. Blatant advertising, party political broadcasts and the rest: our defences are up so it's harder to get through.

• When persuading: don't signal your attempt in advance. Try to divert attention from the persuasion attempt by hiding it within an apparently innocuous message. Emphasise how you are 'just talking' or 'only discussing' something.

• When resisting persuasion: try to spot persuasion attempts that are wrapped up in social pressure or as entertainment. For example: "A little won't hurt. Come on, we're all doing it!" or: "Find out more about [insert politician here]'s secret love child! Tonight on [insert TV network here]".

3. Reactance

People don't like being told what to do or having their freedom restricted. It can even lead to a 'boomerang effect' where telling people not to do something makes them want to do it more.

• When persuading: avoid restricting people's freedom; instead make them feel they have options and room for manoeuvre and this can work to your advantage (see: affirming the right to choose).

• When resisting persuasion: think about whether the persuasion attempt is restricting your freedom. If it is then should you go along with it? Alternatively, is the person emphasising how free you are in order to persuade you?

4. Reality check

After being persuaded, people often perform a sort of reality check. Have I agreed to something I didn't mean to? Would I have agreed if I knew then what I know now? If not, then cancel the whole thing!

• When persuading: don't give people the time for a reality check. Under time pressure people find it difficult to think.

• When resisting persuasion: take a time-out afterwards to think about whether you would still agree to it. Watch out for time pressure or limited deals—these are designed to short-cut rational processes and make us jump right in.

5. Counter-arguing and bolstering

It's the most natural defence of all: thinking about why they are wrong (counter-arguing) and you are right (bolstering).

• When persuading: strongly held beliefs are difficult to attack. Try being sneaky and sidestepping them. Minimise your point to make it less threatening or make the relationship seem more collaborative ("Hey, I'm just trying to work out the truth as much as you buddy.")

• When resisting persuasion: think about who else agrees with you. This bolsters your position by using social confirmation. Be wary of camouflaged attempts to persuade.

6. Resistance breeds more resistance

When people successfully defend themselves against an attempt at persuasion, their original position gets stronger. Say I'm trying to talk you into dying your hair blue and you think you'll look ridiculous. Unless I put forward a better case than, "Because it'll be funny", you'll be even more against it afterwards.

• When persuading: make your first attempt to persuade a strong one, don't go in half-hearted or you could just increase resistance in the long-run.

• When resisting persuasion: if you know the persuasion attempt is coming and you have counter-arguments ready then your resistance will only make you stronger.

7. Attack authority

Persuasion attempts often use the argument from authority, kind of like: "I'm your father so I know best." But like any child, we want to rebel so we attack authority.

• When persuading: make sure your credentials are rock-solid. If they're not, find someone whose authority is unquestioned. People naturally defer to those who have (or appear to have) authority.

• When resisting persuasion: attack the source of the message. Use negative emotions like anger or irritation and attribute them to the so-called authority figure. Be extremely suspicious of anyone who relies purely on authority to influence.

8. Being sharp and alert

Resistance is easiest when we feel sharp and alert. That's when you are better able to raise counter-arguments, sustain your position, spot persuasion attempts coming and so on.

• When persuading: when people are tired, their defences are down. If they are alert now, can they be worn down or their resistance blunted by a frontal attack? And, can you reduce their motivation to resist?

• When resisting persuasion: beware tiredness. Never go shopping when you're really hungry, buy a car when you're desperate or talk to a salesman when you're half-distracted. Recognise times when you're likely to be weak and closet yourself until the energy levels are replenished.

9. Not listening

Sometimes the easiest ways of resisting persuasion are the simplest. You walk away, turn off the TV or block out the drone of other people's point of view by humming the theme to The A-Team.

• When persuading: do you have their full attention? If not, then it's hard to be effective. Once they are focused on you, start with the most interesting part of the argument to draw them in.

• When resisting persuasion: are you really ignoring it? We are more easily swayed than we think. Most guess that it's other people who are influenced by adverts or political messages, not ourselves. Don't just turn it down, turn it off.

Image credit: zen

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

In his new book, Jeremy Dean--psychologist and author of PsyBlog--looks at how habits work, why they are so hard to change, and how to break bad old cycles and develop new healthy, creative, happy habits.

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

Reviews

The Bookseller, “Editor’s Pick,” 10/12/12

“Sensible and very readable…By far the most useful of this month’s New You offerings.”

Kirkus Reviews, 1/1/13

“Making changes does take longer than we may expect—no 30-day, 30-pounds-lighter quick fix—but by following the guidelines laid out by Dean, readers have a decent chance at establishing fulfilling, new patterns.”

Publishers Weekly, 12/10/12

“An accessible and informative guide for readers to take control of their lives.”

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

May 23, 2013

The Anchoring Effect: How The Mind is Biased by First Impressions

To illustrate the anchoring effect, let's say I ask you how old Mahatma Gandhi was when he died.

For half of you I'll preface the question by saying: "Did he die before or after the age of 9?" For the other half I'll say: "Did he die before or after the age of 140?"

Obviously these are not very helpful statements. Anyone who has any clue who Gandhi was will know that he was definitely older than 9; while the oldest person who ever lived was 122. So why bother making these apparently stupid statements?

Because, according to the results of a study conducted by Strack and Mussweiler (1999), these initial statements, despite being unhelpful, affect the estimates people make.

In their experiment, the first group guessed an average age of 50 and the second, 67.

Neither was that close, he was actually assassinated at 87; but you can still see the effect of the initial number.

The anchor state

These might seem like silly little experiments that psychologists do to try and suggest that people are idiots, but actually it's showing us something fundamental about the way we think. It's so basic to how we experience the world that we often don't notice it.

We have a tendency to use anchors or reference points to make decisions and evaluations, and sometimes these lead us astray.

This sort of things is going on in loads of different areas of our lives. Take the emotions for starters. Psychologists have found it can be difficult to predict our future emotions and one reason is that we are anchored in how we feel right now.

That's why people who have just had lunch feel like they'll never be hungry again; compared with those who haven't, who don't display the same short-sightedness (I have described the relevant study in the context of the projection bias).

Real estate agents, car sellers or negotiators will be nodding their heads. That's because anchors are vital in all these lines of work, and many more. The initial price you set for the car, house or, more abstractly, for a deal of some kind, tends to have ramifications right through the process of coming to an agreement. Whether we like it or not, our minds keep referring back to that initial number.

That doesn't mean you just set the highest possible price you can get away with (although in reality that's often what is done). In real life things are more complicated than the Gandhi experiment. People usually have a choice about which house or car to buy or which deal to take and they can always walk away.

Still, there's a good reason sticker prices on car forecourts are mostly so high.

You can see the same effect in salary negotiations. There's some evidence that when the initial anchor figure is set high, the final negotiated amount will usually be higher (Thorsteinson, 2011).

Incidentally, the anchoring effect is another reason that you should open negotiations rather than waiting for the employer to tell you the range: because then you can set the anchor higher (more on this in: Ten Powerful Steps to Negotiating a Higher Salary).

Looking for confirmation

Since the anchoring effect occurs in so many situations, no one theory has satisfactorily explained it. There is, though, a modern favourite for explaining the anchoring effect in decision-making. It is thought to stem from our tendency to look for confirmation of things we are unsure of.

So, if I'm told the price of a particular diamond ring is £5,000, I'll tend to search around looking for evidence that confirms this. In this case it's easy: plenty of diamond rings cost about that, no matter the value of this particular ring. For all I know about diamond rings it could be worth £500 or £50,000.

The problem is that this explanation is less satisfying when the anchor is so manifestly unhelpful, like when you tell people that Gandhi was older than nine when he died.

Perhaps, then, it's all down to our fundamental laziness. When given the Gandhi example we can't be bothered to make the massive adjustment from the anchor we're given up to the real value, so we go some way and then stop.

How to avoid the anchoring effect

Whatever the reason for it, the anchoring effect is everywhere and can be difficult to avoid. That's especially true when we are deciding what to pay for stuff since we are overly influenced by the price that's been set.

One way of avoiding this bias—whether it's emotional or in decision-making—is by trying to wriggle free from the anchor state.

This can be done by thinking about other comparisons. That's what we're doing when we comparison shop: getting some new price anchors. In the realm of the emotions it might mean trying to compare with other emotional states, not just how you feel right now (creating a 'memory palace' for reference emotions may help with this). When negotiating it might mean thinking about what the other options are (negotiation theorists call this the 'BATNA': the Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement).

Alternatively, for nullifying the anchoring effect in decision-making, find out more about the area: experts are less susceptible to it.

There's little doubt it's hard, though: some studies suggest that even when you know about it and are forewarned, the anchoring effect can still affect our judgements. It just shows the power that first piece of information can have on how we make decisions.

Image credit: Hey.Pictrues

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

In his new book, Jeremy Dean--psychologist and author of PsyBlog--looks at how habits work, why they are so hard to change, and how to break bad old cycles and develop new healthy, creative, happy habits.

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

Reviews

The Bookseller, “Editor’s Pick,” 10/12/12

“Sensible and very readable…By far the most useful of this month’s New You offerings.”

Kirkus Reviews, 1/1/13

“Making changes does take longer than we may expect—no 30-day, 30-pounds-lighter quick fix—but by following the guidelines laid out by Dean, readers have a decent chance at establishing fulfilling, new patterns.”

Publishers Weekly, 12/10/12

“An accessible and informative guide for readers to take control of their lives.”

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

May 20, 2013

How to Pick a Winner: A Psychological Trick to Improve the Odds

I'm not, as they say, a betting man; but if I were I'd put down the form book and spend my time studying a new paper by Yoon et al. (2013) published in Psychological Science.

The Korean researchers are fascinated by the question of whether thinking more carefully about a bet can actually make you less likely to win.

In their first test of the idea they looked at 1.9 billion bets placed on baseball and soccer through a Korean company called "Sports ToTo". They wanted to see how people did when betting just on who won compared with when they tried to predict the exact score.

Obviously getting the final score right is harder than just predicting the outcome; but when you guess the score, you are also predicting the outcome.

What they found was that across all the games, when people made a bet on the score they won 42.2% of the time, but when they just tried to predict the outcome they were right 44.4% of the time.

Not a massive difference admittedly and it could just be a statistical anomaly or something to do with the way people bet through this company. So they then took this finding to the lab to see if they could replicate it under controlled conditions...

The experiments

Participants in three experiments made predictions on the 2010 World Cup, the 2012 European Football Championship and the 2011 Asian Cup. For each event, half the participants tried to predict the score, while the other half just tried to predict the outcome.

This time the superiority of just predicting the outcome rather than the exact score was clearer. On the World Cup performance went up from 41.4% for the exact sore to 46.5% for the outcome; on the European Championship it went up from 47.8% to 53.5% and on the Asian cup it went up from 45.8% to 50.4%.

In other words people predicting just the outcome rather than the score increased their chances of being correct by about 5%.

Think global

What's going on here? Why do people do better at calling these matches when they just predict the score rather than being more specific?

The researchers think it's essentially because by trying to be too specific, we trip ourselves up. For example when you try to guess the score of a soccer match, you are more likely to focus on specific factors like the form of the striker, their goalie's recent divorce settlement or the colour of the manager's shirt. In doing so you neglect the fact that the match is an away fixture.

When you just try to predict the outcome of the match, though, you'll tend to take a more global view. This encourages you to concentrate mainly on really important factors.

So, will these results generalise to other decisions outside sporting events? Is it better not to think too specifically about a job candidate's skill-set or a potential partner's Toby jug collection?

Who knows? But it's a nice example of when concentrating too much on specific details gets in the way of effective decision-making. And we've all done that.

Image credit: Roger Price

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

In his new book, Jeremy Dean--psychologist and author of PsyBlog--looks at how habits work, why they are so hard to change, and how to break bad old cycles and develop new healthy, creative, happy habits.

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

Reviews

The Bookseller, “Editor’s Pick,” 10/12/12

“Sensible and very readable…By far the most useful of this month’s New You offerings.”

Kirkus Reviews, 1/1/13

“Making changes does take longer than we may expect—no 30-day, 30-pounds-lighter quick fix—but by following the guidelines laid out by Dean, readers have a decent chance at establishing fulfilling, new patterns.”

Publishers Weekly, 12/10/12

“An accessible and informative guide for readers to take control of their lives.”

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

May 15, 2013

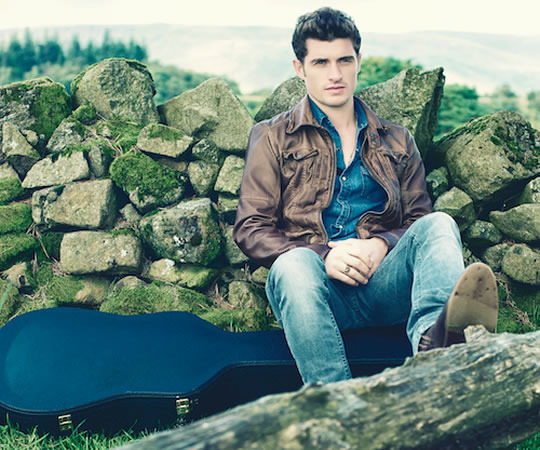

The Incredible Dating Power of a Guitar Case

In France there's a psychologist, Professor Nicolas Gueguen, who roams the North-West, asking young women for their telephone numbers—or at least his research assistants and experimental confederates do.

This isn't just to boost the national stereotype, but all in the name of science.

The results they've reported over the years confirm some things we think we already know and a few new insights. His experiments often involve approaching random strangers (usually women) in the street and asking them for something (usually their phone number). So far he's found that:

Men getting out of expensive versus cheap cars are more likely to get the numbers of passing women.

A fire-fighter's uniform makes women more likely to divulge the digits.

A touch on the forearm makes a man more likely to get a woman's number (it also works on men, see 10 Psychological Effects of Nonsexual Touch).

And, on a slightly different tack, why loud music in bars increases alcohol consumption.

Now, in his latest experiment, he's been testing the pulling power of musicians. How much extra sheen does it give a man if he's carrying a guitar case when he asks a woman for her number?

Naturally women are pretty cagey when approached by random strangers in the street, so Gueguen et al. (2013) chose a young man who had been highly rated by a panel of women.

He was told to stand in a local shopping centre and approach women of between 18 and 22, without regard to their appearance, and say to them:

"Hello. My name’s Antoine. I just want to say that I think you’re really pretty. I have to go to work this afternoon, and I was wondering if you would give me your phone number. I’ll phone you later and we can have a drink together someplace."

Then he smiled and gazed into their eyes. The poor chap had to do this in three different conditions while holding either:

a guitar case,

a sports bag or,

no bag at all.

What happened was that when he wasn't holding anything he got a number 14% of the time. The sports bag, though, put women off and dropped his average to just 9%.

It was the guitar case that did the trick, bumping up his chances to 31%. Not bad at all considering he was approaching random strangers in the street.

So the mystical, romantic image of the musician had a pretty powerful effect. Well, it will until she discovers the guitar case only has a sports bag inside.

(No mention is made of what the young man did with all the telephone numbers, but I'm sure they were dealt with ethically.)

Image credit: Kris Kesiak

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

In his new book, Jeremy Dean--psychologist and author of PsyBlog--looks at how habits work, why they are so hard to change, and how to break bad old cycles and develop new healthy, creative, happy habits.

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

Reviews

The Bookseller, “Editor’s Pick,” 10/12/12

“Sensible and very readable…By far the most useful of this month’s New You offerings.”

Kirkus Reviews, 1/1/13

“Making changes does take longer than we may expect—no 30-day, 30-pounds-lighter quick fix—but by following the guidelines laid out by Dean, readers have a decent chance at establishing fulfilling, new patterns.”

Publishers Weekly, 12/10/12

“An accessible and informative guide for readers to take control of their lives.”

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

May 13, 2013

How to Help Other People Change Their Habits

Having written a book on how to change your own habits, in interviews I was often asked: how can I change another person's habits?

Say I want my partner to stop cracking his knuckles or get my daughter to put down her mobile phone at meal times or start someone else exercising: how do I do that?

It's not something I cover in the book, which focuses mainly on how habits work, how much of our everyday lives they influence and how to change your own personal habits.

Ultimately the same techniques apply; but when you are working on someone else, you've got to take a few steps back. Do they want to change? If not, can you persuade them? How will this attempt to change them affect your relationship?

Then, if you manage that, you can move on to using all the same techniques that you might use on yourself.

So here are three preliminary things to think about when trying to change someone else's habits:

1. Are they open to change?

First up, and most obviously, people have to be open to the possibility of change.

People can be very defensive about their habits. They've taken years to develop and have become part of their identity; alternatively they are simply ashamed of them and want to try and justify them.

So, you may want your partner to stop cracking his knuckles or spending all his time on his smartphone, but is he open to the possibility that something might be done?

If not then even broaching the subject may be a waste of time. But let's say you think they might be open to change, that brings me on to...

2. Being non-judgemental

One thing therapists are taught when dealing with patients is to be non-judgemental. There's a good reason for that: it's not just that no one likes to be judged, but that it sets the wrong tone. The wrong tone is: I know best what's good for you and I'm telling you what to do. Not many people want to be ordered around like a dog.

The right tone has you both on an even footing and is warm and supportive. You're a helpful friend who is interested in their well-being but is still accepting who they are.

As you can imagine, this can be a difficult balance. But, for most people, just avoiding being judgemental is a really great start. We humans seem to love passing judgement on anything and everything and it's a difficult habit to give up.

3. Increasing their self-awareness

Along with detecting the seeds of change and being non-judgemental, one of the main things you can help someone else with is their self-awareness.

It's a central feature of habits is that people perform them unconsciously and repeatedly in the same situations. To name a few good habits: we brush our teeth in the bathroom, look both ways before we cross the road and put our seatbelts on in the car before we pull away.

A vital step in changing a habit, then, is identifying the situation in which it occurs. You can help other people identify the situations by gently pointing out what seems to prompt them to perform the habit. For example, are there particular emotions or physical situations that are associated with the habit?

If so, making the other person aware of these can help them change that habit.

Working together

So getting other people to change is firstly about backing up from the techniques of habit change and seeing if the other person is open to tweaking their behaviour. You can't make other people change if they don't want to.

After this you can move on to all the techniques I describe in the book. I've listed some of these in my article on how to make New Year's resolutions. These include things like choosing an alternative behaviour, making specific plans, thinking about things that are likely to trip them up, and so on.

These three pointers are just to get you started and by no means cover all bases. For children things are slightly different, for more seriously ingrained and destructive habits, these are only the beginning. But nevertheless these are a good place to start.

In theory with two people working together to change one person's habit, you are in a stronger position. It's not just that you can be their cheerleader; it's also that you can objectively look at their behaviour and make them aware of connections that might otherwise be mostly or completely unconscious.

Image credit: chantOmO

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

In his new book, Jeremy Dean--psychologist and author of PsyBlog--looks at how habits work, why they are so hard to change, and how to break bad old cycles and develop new healthy, creative, happy habits.

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

Reviews

The Bookseller, “Editor’s Pick,” 10/12/12

“Sensible and very readable…By far the most useful of this month’s New You offerings.”

Kirkus Reviews, 1/1/13

“Making changes does take longer than we may expect—no 30-day, 30-pounds-lighter quick fix—but by following the guidelines laid out by Dean, readers have a decent chance at establishing fulfilling, new patterns.”

Publishers Weekly, 12/10/12

“An accessible and informative guide for readers to take control of their lives.”

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

May 9, 2013

Illusory Correlations: When The Mind Makes Connections That Don’t Exist

To see how easily the mind jumps to the wrong conclusions, try virtually taking part in a little experiment...

...imagine that you are presented with information about two groups of people about which you know nothing. Let's call them the Azaleans and the Begonians.

For each group you are given a list of positive and negative behaviours. A good one might be: an Azalean was seen helping an old lady across the road. A bad one might be: a Begonian urinated in the street.

So, you read this list of good and bad behaviours about the Azaleans and Begonians and afterwards you make some judgements about them. How often do they perform good and bad behaviours and what are they?

What you notice is that it's the Begonians that seem dodgy. They are the ones more often to be found shoving burgers into mailboxes and ringing doorbells and running away. The Azaleans, in contrast, are a sounder bunch; certainly not blameless, but overall better people.

While you're happy with the judgement, you're in for a shock. What's revealed to you afterwards is that actually the ratio of good to bad behaviours listed for both the Azaleans and Begonians was exactly the same. For the Azaleans 18 positive behaviours were listed along with 8 negative. For the Begonians it was 9 positive and 4 negative.

In reality you just had less information about the Begonians. What happened was that you built up an illusory connection between more frequent bad behaviours and the Begonians; they weren't more frequent, however, they just seemed that way.

When the experiment is over you find out that most other people had done exactly the same thing, concluding that the Begonians were worse people than the Azaleans.

Explaining the illusion

This experimental method is actually from a classic study by Hamilton and Gifford (1976), which is all about how we perceive other people's positive and negative traits. In the experiment, people had different perceptions of the two groups, good for the majority and bad for the minority, purely because they had more information about the majority. It's not hard to see why this sort of process might contribute to the formation of prejudice in society at large.

Now, psychologists have not agreed how to explain this and other types of illusory correlations.

One explanation is that people over-estimate the diagnostic power of infrequent events. In other words: if there is only one Martian who lives in your street and he/she/it listens to skiffle music, then you tend to think that all Martians must like skiffle. On the other hand if half the street is filled with law-abiding Martians, only a few of whom like skiffle, you'll guess that it's only a minority interest.

Others say that illusory correlations are down to how memory or learning works or just a function of incomplete information. Whatever the explanation, we do see these illusory correlations everywhere.

Golf and stock prices

Here's an example of a much less subtle type of illusory correlation from the world of CEOs. When you are deciding what to pay a CEO, what factors do you take into account? I'm sure you can list a few but what about golfing ability? Would you pay a CEO more because they were better at golf? No?

One analysis has looked at the correlation between golfing ability and American CEO pay (Hogarth & Kolev, 2010). It found that as golfing ability improved, their pay went up. Non-golfers were, on average, the lowest paid of all.

And here's the kicker: the better the CEOs were at golf, the worse their stocks performed. So in people's minds being good at golf was associated with more pay, but in reality it was associated with worse performance!

The assumption is that there's an illusory correlation going on here. Somehow it's assumed that because someone is good at golf, they must also be good at other stuff, like running a multinational corporation, and so they get paid more.

Sticking with the business theme, all sorts of illusory correlations exist in equity markets. One sign that traders sometimes use to predict price movements is the 'head-and-shoulders' chart. It's when the stock's price movement looks like a person's head and shoulders: in other words, two smaller peaks with one big peak in between.

Although it's considered a reliable signal, and is associated with increased trading, the head-and-shoulders shape on the chart doesn't profitably predict price fluctuations (Bender & Simon, 2012). It's just another illusory correlation: what our meaning-hungry minds are seeing everywhere.

My favourite types of illusory correlations, though, are like when you turn the light on and there's a power-cut, or when you stamp your foot and there's a simultaneous clap of thunder. For a single moment, you feel like you've got super-powers.

Image credit: Village9991

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

In his new book, Jeremy Dean--psychologist and author of PsyBlog--looks at how habits work, why they are so hard to change, and how to break bad old cycles and develop new healthy, creative, happy habits.

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

Reviews

The Bookseller, “Editor’s Pick,” 10/12/12

“Sensible and very readable…By far the most useful of this month’s New You offerings.”

Kirkus Reviews, 1/1/13

“Making changes does take longer than we may expect—no 30-day, 30-pounds-lighter quick fix—but by following the guidelines laid out by Dean, readers have a decent chance at establishing fulfilling, new patterns.”

Publishers Weekly, 12/10/12

“An accessible and informative guide for readers to take control of their lives.”

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

May 7, 2013

Perform Better Under Stress Using Self-Affirmation

Have a look at the following list of values and personal characteristics. If you had to pick just one, which most defines who you are and what matters to you?

Your family

Being good at sports

Belief in a higher power

Your friends

Your creativity

Aesthetics

Your job

Perhaps what matters most to you isn't there (this isn't a comprehensive list!), in that case think about what does matter to you most.

In the burgeoning series of experiments which use this type of self-affirmation exercise, participants are then asked to write a paragraph or two on why this characteristic or value is so important to them. Sometimes they also think about a specific time or story that is illustrative.

The effects can be quite useful across a surprisingly large number of domains. It can help boost self-control in the moment and even increase social confidence for two or more months after it's carried out.

Problem-solving

In a new study, Cresswell et al. (2013) tested whether a simple self-affirmation exercise would have a beneficial effect on problem-solving under stress, particularly for individuals who have been stressed recently.

In their experiment, half the participants did the self-affirmation exercise while the rest performed a similar, but ineffectual exercise.

The results showed that those who had been stressed recently and were self-affirmed before they began the exercise performed better at the problem-solving task. This suggests the self-affirmation exercise could be useful for people under stress who are, for example, taking exams, going to job interviews or under pressure at work.

What's fascinating about the self-affirmation task is that it doesn't have to be related to the area in which you're looking to improve. So thinking about the importance of your family can increase your problem-solving performance, even though the two have little in common.

We don't know exactly why the self-affirmation exercise works; indeed the researchers tested a couple of options in their study—that perhaps it improves people's mood or that they engaged more with the task—but they don't find evidence for either.

Instead they think it more likely that the self-affirmation exercise helps you move your attention more flexibly, which improves memory function.

Whatever the mechanism, this growing body of evidence on the benefits of self-affirmation is encouraging.

Image credit: Vu Bui

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

In his new book, Jeremy Dean--psychologist and author of PsyBlog--looks at how habits work, why they are so hard to change, and how to break bad old cycles and develop new healthy, creative, happy habits.

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

Reviews

The Bookseller, “Editor’s Pick,” 10/12/12

“Sensible and very readable…By far the most useful of this month’s New You offerings.”

Kirkus Reviews, 1/1/13

“Making changes does take longer than we may expect—no 30-day, 30-pounds-lighter quick fix—but by following the guidelines laid out by Dean, readers have a decent chance at establishing fulfilling, new patterns.”

Publishers Weekly, 12/10/12

“An accessible and informative guide for readers to take control of their lives.”

→ "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", is available now on Amazon.

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

May 1, 2013

Power Up: The Performance Benefits of a Simple Mental Exercise

"Have successful professionals always been successful? Take Francesca Gino. An Associate Professor at Harvard, she is considered by many to be a superstar.

But things did not always look so bright for her: two years in a row she gave job talks at a number of top 10 schools and universities, but got no offers from those schools. Yet, in 2009, everything suddenly turned up roses; she got offers from Harvard, Wharton, Berkeley, and New York University. What had changed?

Well, clearly she was older and wiser. But she also changed her pre-talk ritual: before each campus talk and interview she sat down and wrote out a reflection of a time in which she had power." (Lammers et al., 2013)

An inspiring story, certainly, which suggests a simple way to improve your performance in job interviews and probably in other situations where boosting the feeling of power is important.

All you do is sit down beforehand and reflect on a time when you had power. By doing this you are activating your own personal sense of power.

OK, though, but as a scientist I have to be sceptical of anecdotes. This may have worked for Professor Gino, but perhaps she just got better at interviews or her talent was finally recognised. That's why a new study led by Dutch psychologist, Joris Lammers, is so interesting.

What they did across two experiments was have some people write application letters for an imaginary job and others actually do a 15-minute face-to-face interview (Lammers et al., 2013).

For both the application letter and the interview studies, though, the researchers manipulated how much power they felt:

Application letter experiment: before they wrote the letter, half the participants wrote about a time when they had power and half about a time when they didn't.

Interview experiment: one-third of participants wrote about a time they had high power, one-third low power and the final third didn't write about anything beforehand.

Here are the results:

Application letter experiment: people expressed a little more self-confidence when they thought about high-power situations beforehand, compared with lower power situations.

Interview experiment: in the mock interview, 47% of participants who didn't write anything in advance were accepted for the 'job'. This went up to 68% when they wrote about a high power situation and down to only 26% for those who wrote about feeling low in power.

This shows that the exercise of writing about a high-power situation before a job interview can be beneficial. It may also be marginally helpful when writing the interview letter.

The researchers chose the job interview situation partly because there's something intensely dis-empowering about it. Everything about it—the evaluation, the continuous requirement for self-justification and evidence—seems designed to sap your self-belief.

Most interviewers prefer to see a confident, assertive individual, but the situation tends to make people meek, defensive and subservient. This exercise may help to counteract this problem.

Still, it's not just in interviews that this exercise is likely to be helpful. Feeling more powerful also makes you feel more confident, more in control and even more optimistic. The list of situations in which that might be useful is endless.

So have a think back to a time when you felt masterful and power up!

Image credit: John 'K'

Did you know that every post on PsyBlog is written by a British psychologist called Jeremy Dean?

Did you know that he has a new book out called "Making Habits, Breaking Habits", now available on Amazon?

You did? Well, carry on then...

→ Download amazing, 100% free e-books on meditation, self-improvement and wisdom by a Himalayan mystic. Go to http://www.omswami.com/p/free-ebooks.html or http://www.omswami.com.

Jeremy Dean's Blog

- Jeremy Dean's profile

- 29 followers