Jeremy Dean's Blog, page 825

February 6, 2013

How to Give The Slip to Persistent Negative Thoughts

Have you ever said a word over and over again until it lost its meaning? It's a trick many discover in childhood which can provide the first inkling that words aren't the solid, dependable, unchanging labels they seem.

Instead words start to feel slippery, open to interpretation and (whisper it) interchangeable.

Anyway, it's a fun game: if you like, try it again now: say your own name over and over again out loud until it loses all meaning.

This is an effect that psychologists have been studying, on and off, for at least a hundred years. The hope is that if words can come to have no meaning through repetition then perhaps negative ideas and thoughts can be tackled in the same way.

Nowadays repeating words over and over again is part of a therapeutic technique called cognitive diffusion. The theory goes that if you have negative habitual thoughts going around in your head all the time, then perhaps their power can be diffused through repetition.

Some psychologists see it as particularly useful in the treatment of depression. That's because one of the cognitive components of depression is negative automatic thoughts. These are things like repeatedly thinking to yourself: "I am worthless," or "I am an idiot."

People experiencing depressive episodes often find that these types of thoughts go around in their heads endlessly.

In theory, then, it may be possible to tackle automatic negative thoughts by trying to diffuse their meaning (remember, suppression doesn't work and has all sorts of weird consequences).

What therapists do is extract the essence of the thought, for example "idiot", and get the patient to repeat it over and over again.

What you'll be asking, as did I when I came across it: is there evidence that it can work? And if you've been reading PsyBlog for a while, you'll know I wouldn't mention it unless there was!

In a recent study Masuda et al. (2010) recruited 147 participants, only a few of whom had mental health problems. Each person identified a negative thought about themselves and boiled it down to one word like 'idiot', 'fat' or 'angry'. Then each person rated how uncomfortable that word made them feel and how much they believed it referred to them.

The participants were split into five groups. In one of them they repeated the word over and over again as fast as they could for 30 seconds, before rating the associated discomfort and believability again.

The results showed that in comparison to other techniques including distraction, a control condition and a weaker diffusion condition, it was the full cognitive diffusion that worked best. Participants in this condition experienced the largest decreases in the thought's believability and associated discomfort. Even those who had confirmed depressive symptoms found the exercise useful.

Like repeating your name over-and-over again, the effect does wear off. In the long-term it is better to try and change the content of these thoughts, or at least your relationship with them.

Still, there is some new evidence emerging that cognitive diffusion can be useful in the longer-term (Deacon et al., 2011).

But in the meantime, sometimes we need to reduce the impact of a thought for a while and even a short respite can help us think more clearly in the moment. When next you need to do that, try it, see what happens.

Image credit: Wasfi Akab

New Book: Making Habits, Breaking Habits

New Book: Making Habits, Breaking Habits

About 50% of our everyday lives is habitual. While we're awake, then, about half the time we are repeating the same actions or thoughts in the same contexts. Automatically. Without thinking. It's part of the reason change is so hard.

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits', distils the results of hundreds of studies containing thousands of participants, to give you a blueprint for how to create new habits and tackle bad ones, whatever they are, and how to make it automatic so that willpower is no longer an issue.

→ You can dip into the first chapter, or check it out on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

February 5, 2013

Food on the Mind: 20 Surprising Insights From Food Psychology

We invest food with so much meaning, and rightly so: it changes our mood, it strengthens our relationships when we eat together and food choices express who we are.

But food has a dark side. We worry about eating unhealthy, about weight gain and how we can control our intake. Eating is not just pleasure; it is also about the struggle with ourselves.

In the last few decades we've learnt an enormous amount about the psychology of food. Here are 20 of my favourite findings.

1. America's terrible relationship with food

Americans have a very dysfunctional relationship with food.

Compared with the French, Belgians and Japanese, Americans get less pleasure from food and are most obsessed with whether it is 'healthy' or not (Rozin et al., 1999).

In contrast, the French have fewer hang-ups and enjoy their food the most. Perhaps it's no coincidence that they are also half as likely to be obese as Americans.

Americans, then, get the worst of all worlds: they are more dissatisfied with what they eat, are more concerned about whether it is healthy, try to make more dietary changes and are twice as likely to be obese as the French.

Something has clearly gone badly wrong with America's relationship with food.

2. You don't know when you're really full

We tend to think that the amount of food we eat is a result of how hungry we are. It's a factor, but not the only one. We are also affected by the size of the plates, serving spoons, packets and so on.

This has been most memorably demonstrated in a study where participants ate out of a soup bowl that was filled up secretly from under the table (Wansink et al., 2005). Others were served more soup in the usual way. Those eating out of the magically refilling bowl had almost twice as much soup but felt no less hungry and no more full.

The moral of this strange tale is that our stomachs provide only crude messages about how much we've eaten. Instead we rely on our vision and the eye is easily fooled.

Here's my healthy eating tip: force yourself to buy smaller packets of everything. Oh, and get rid of your automatically refilling soup-bowls: they're really doing you no good at all.

3. Fat = bad?

This is a great example of the law of unintended consequences.

Many people have come to believe that high-fat food is bad. Public health campaigns, books and articles in the 80s promoted this idea.

Here are the problems. Not all fats are bad; in fact some are very good, necessary parts of our diet. As a result people avoid small snacks with high-fat content in favour of large snacks with low-fat content. In reality the low-fat snack may have way more calories simply because it's much bigger.

Because people think that fat=bad, some foods get unfairly categorised as bad for us, while other low-fat foods are supposed to be good. This leads to the situation were people regularly under-estimate the amount of calories in low-fat, 'good' foods and over-estimate the calories in high-fat 'bad' foods (Carels et al., 2006). The difference in that study worked out to about 35%.

The same is true in restaurants where dishes billed as 'healthy' are estimated by diners to contain up to 35% less calories than they really do.

4. It's never 'just lunch'

Eating together has powerful psychological overtones.

Lunch is a serious undertaking, especially when it's with an ex-partner, according to a study by Kniffin and Wansink (2012). They found that compared with things like having a coffee or talking on the telephone when their partners had lunch with an old flame, it provoked the most jealousy.

The symbolic power of eating with other people is strong: it's never 'just lunch'.

5. Taste fades with age

As we age, our sense of taste gets weaker. One study found that the ability to detect salt was most affected, as was the ability to detect 'umami', now considered one of the basic tastes, along with sweet, sour, salty and bitter (Mojet et al., 2001).

Depending on the exact taste, older people may need between 2 and 9 times as much of a condiment like salt to experience the same taste. Men seem to be particularly affected by this loss in the ability to taste.

The reason is partly that older people have fewer taste buds but mainly that the sense of smell weakens with age. We actually taste much of our food with our noses, so when the nose doesn't work so well, taste sensation is lost as well.

6. Carrots taste weird for breakfast

We tend to think that there's something intrinsic about say, a carrot, that means we either like it or don't. But a simple thought experiment shows this isn't true.

What if you had to eat a carrot, on its own, at six o'clock in the morning? Does it taste the same then as it does mixed in with other vegetables and meat, and eaten at the 'usual' time of day?

No.

The context in which food is eaten affects us much more than we might imagine. This includes the time of day, who is around us and where we are.

7. Fat waitress = fat customer

Here's a case in point for how context affects what you might choose from the menu in a restaurant. McFerran et al. (2010) looked at how the effect of your server's body-weight might affect what you choose.

They found that people who were dieting ate more food when encouraged to choose unhealthy snacks by an obese waitress than when the waitress was thin. You might have predicted exactly the reverse result—surely an obese server will put you off your food. Apparently not. Instead it may unconsciously give people who are dieting 'permission' to overeat. In other words: if she can overeat, so can I!

Incidentally exactly the opposite effect was seen for those who weren't dieting. They ended up eating more when the waitress was thin. This may be simply because attractive (thin) people tend to be more persuasive.

8. Fat friends = fat self

It's probably going too far to say that having fat friends causes us to be fat ourselves, although there is evidence for this. Christakis et al. (2007) found that people's chance of being obese was increased by 57% if they had obese friends.

Still, it's very safe to say that people are enormously influenced by the eating behaviour of those around them. We clearly see in studies that people eat more when those around them eat more, and less when those around them eat less. Women seem particularly susceptible to this.

Even while eating on our own we are indirectly influenced in our choices by society—psychologists call these 'social norms'. When norms are manipulated in experiments, people can be made to eat less or more at will.

One great example is that manly men are thought to eat big meals and feminine women eat small meals. Hence: a steak for the 'gentleman' and a salad for the 'lady'.

9. Eating intentions are beaten by habits

What's the best way to predict what food you're going to eat tomorrow? Should I ask about your intentions, your preferences or that diet you've just started?

Don't bother. All I need to do is ask you what you ate yesterday. The best way to predict what you're going to eat tomorrow is to examine your habits. On average habits tend to trump our best intentions and even our stated preferences.

Changing our eating habits is hard because so many decisions are made automatically, in response to routine situations we find ourselves in, and also because of...

10. Mindless eating

Eating is so routine that we easily zone out from the experience. While our minds are wandering, though, our hands are shovelling it in faster and faster.

Studies have shown that people eat more when they are distracted, like when watching TV or talking with friends (Bolhuis et al., 2013). Unfortunately when not focusing on our food, we tend to eat more and get less enjoyment from it.

This is why one approach that's used to combat eating disorders and obesity is mindful eating. This is taking smaller bites and paying more attention to what you are eating. Not only do people eat less this way, but they also enjoy it more.

11. Suppressing food thoughts leads to bingeing

Regular readers of this blog will probably be bored witless with me going on about how trying to suppress a thought makes it come back stronger. Sorry. Here we go again.

The same is true for food. People on diets who habitually try to suppress their thoughts about food are more likely to experience food cravings as well as being more prone to binge eating (Barnes & Tantleff-Dunn, 2010).

So, don't try to avoid, instead try these 8 alternatives to thought suppression.

12. If it's healthy, you can eat more!

Unfortunately this seems to be a widely held belief, or at least way of behaving. In studies, when people are given the same food, but in one instance it is labelled more healthy, they will eat more than when it is labelled unhealthy. In Provencher et al. (2009), it was 35% more.

It's another situation in which so-called healthy foods can be bad for us because they encourage higher consumption.

13. Anyone for smoked salmon ice-cream?

Food labels and the expectations they set up have all kinds of effects on how we experience food. Most people have now heard about the studies where they put fancy labels on ordinary bottles of wines and magically people say they taste better. It's the same effect if you tell people the wine is really expensive (read more here).

Here's a weirder one, though. Researchers came up with a strange new concoction: smoked salmon ice-cream (Yeomans et al., 2008). But they told some people it was a new type of ice-cream and another group that it was a frozen savoury mousse.

People hated the food when they were told it was a type of ice-cream, but found it acceptable when told it was a mousse.

So it's all very well putting fancy labels on things, but they've got to set up the right expectations.

14. Label it full-fat and it tastes better

Forget about weird ice-cream, what if you take the same food and give it to some people telling them it is 'full-fat' and others that it's 'low-fat'?

Well, they say that the 'full-fat' option tastes better, but they eat less (Wardle & Solomons, 1994). This effect seems to be strongest for people who are most worried about the effect of the food they eat on their health (Westcombe & Wardle, 1997).

15. Bad moods make you eat bad stuff

'Emotional eating' is the idea that the emotions, not just hunger, affect how and what we eat. There is some truth to this.

In experiments, generally when people are put in a bad mood, they are more likely to reach for sugary and high-fat snacks. Negative emotions also make people prefer a snack rather than a proper meal and eat fewer vegetables.

Unfortunately good moods don't necessarily make you eat good stuff. People do seem to eat more when they are in a good mood, but just more of everything rather than specific foods.

16. Healthy foods improve your mood

We know that people who eat more fruit and vegetables are generally more satisfied with life and happier, but we couldn't be sure that it was the fruit and vegetables that were really causing it.

The very latest research, however, suggests that eating fruit and vegetables one day can actually improve your mood the next day (White et al., 2013). This is based on the idea that micronutrients like folates found in fruits and vegetables can help improve depression.

In their 21-day study White et al. (2013) asked participants to log how much fruit and vegetables they ate as well as their mood. This showed that eating more fruit and vegetables one day actually predicted mood the next day. However, they needed to eat 7 or 8 servings for the effect to be clear. So the oft-recommended 5 portions may not be enough to get the full boost to mood.

17. I won't have what she's having

Have you ever been to a restaurant in a group, chosen what you're going to eat, then heard a couple of other people order the same thing and changed your mind?

According to one study this is a recognisable trend (Ariely & Levav, 2000). One of the causes is the desire to be individual and stand out. Ordering something different seems to express individuality.

The punch-line, however, is that in Ariely & Levav's study, people enjoyed their second choices less than their first. Sometimes being different for the sake of it is a kind of conformity (see what I did there to make you feel better about ordering the same thing as other people? Go on, have what you really want!).

18. Small changes beat weird crash diets

If you want to lose weight, forget all those weird diets, whatever they are. The latest fad is the 5:2 diet where you eat normally for five days and fast for two. There's almost no evidence this works. These sorts of extreme diets require big changes to habits, which, as I describe in my book, are hard to make.

Instead of all those crazy diets, it's much better to make small changes that are sustainable in the long-term: by which I mean the rest of your life. Participants in a recent online healthy eating study made very small sustainable changes to their habits and succeeded in losing weight (Kaipainen et al., 2012). Note that they lost weight without going on a diet!

The habits to adopt included: put down your utensils between bites, use smaller plates, drink water with every meal or snack and don't eat directly from the package. It was that simple.

19. The Pepsi challenge

In the same way that lunch is never 'just' lunch, food is never 'just' food. It can also represent an idea and that can influence how we experience the food itself.

Here's an example: Allen et al. (2008) did a version of the Pepsi challenge. Participants were given either Pepsi or a store-brand cola to assess.

Pepsi's advertising encourages the idea that life should be exciting and full of enjoyment whereas store-brand cola doesn't particularly have any marketing message.

The results showed that those who most strongly agreed that life should be full of excitement thought the cola they were told was Pepsi was more tasty. The trick was that often they were just drinking the store-brand cola.

So it's not just the actual taste that affects our evaluations but the beliefs we have about that food or drink.

20. I'm eating an idea and it's a tasty one!

What weird foods have you eaten? Fried bat or tarantulas, an ox penis or tuna eyes?

Perhaps you've been involved in this type of conversation. People start listing all sorts of exotic foods they once tasted—each trying to outdo the last. What's that about? According to one theory we don't just eat food, we eat ideas.

'Conceptual consumption' is our desire to tick boxes on our experiential CVs.

People know, for example, that bacon ice-cream will taste unusual, but there is a clear pay-off in conceptual consumption. It's not just bragging rights, they also like the very idea of each of these things and they want to 'possess' the experience.

It's also about self-image. People want to see themselves, and be seen by others, as interesting people who choose a variety of different experiences for themselves. (Hence the fried-bat-chat.)

Image credits: lallou & sea turtle & Kathrin and Stephan Marks & Robert Fornal

New Book: Making Habits, Breaking Habits

New Book: Making Habits, Breaking Habits

About 50% of our everyday lives is habitual. While we're awake, then, about half the time we are repeating the same actions or thoughts in the same contexts. Automatically. Without thinking. It's part of the reason change is so hard.

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits', distils the results of hundreds of studies containing thousands of participants, to give you a blueprint for how to create new habits and tackle bad ones, whatever they are, and how to make it automatic so that willpower is no longer an issue.

→ You can dip into the first chapter, or check it out on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

January 31, 2013

Sway: The Psychology of Indecision

A lot of stuff in life provokes that feeling of ambivalence where we can't quite decide which way to go.

Both sides of an argument are persuasive or both plans for the weekend are equally attractive.

We lean one way, then the other. We feel ourselves wavering or saying: "Well, on the one hand...but on the other hand..."

Our minds are metaphorically wavering but do we perhaps also physically enact being torn between two decisions or two points of view?

A new study by Schneider et al. (2013) has tested this out using a fiendishly simple method. They had participants read two different articles about abolishing the minimum wage for adults:

The first just stated the case for abolishing the minimum wage.

The second listed both pros and cons.

As they read the article they stood on a Wii Balance Board (right) which was used to measure how much they moved from side-to-side.

As they read the article they stood on a Wii Balance Board (right) which was used to measure how much they moved from side-to-side.

Sure enough, those who read the article containing the pros and cons really did move from side-to-side more than those who read the one-sided article. So, in situations in which people are wavering they do actually physically move to indicate they are torn.

But, after thinking about the article for a bit, they were asked to make a decision. The Wii Balance Board showed that when they did this, they really did 'take a stand' and lessened their side-to-side movements.

The cool thing is that it worked the other way around as well.

Researchers approached people in the park and told them a cover story about how they were investigating tai-chi movements. The results of this second study showed that those told to enact side-to-side movements felt more ambivalence than those carrying out up-and-down or no movement at all.

This suggests that this feedback between mind and body works both ways. We move from side-to-side when we feel ambivalent and starting to move from side-to-side can also cause us to feel more ambivalent about whatever we are thinking about.

We don't know from this study but swaying from side-to-side may well help us make up our minds.

→ Like things like this on 'embodied cognition'? Check out 10 Simple Postures That Boost Performance and Five Effortless Postures that Foster Creative Thinking.

Image credit: Mitchell Joyce

New Book: Making Habits, Breaking Habits

New Book: Making Habits, Breaking Habits

About 50% of our everyday lives is habitual. While we're awake, then, about half the time we are repeating the same actions or thoughts in the same contexts. Automatically. Without thinking. It's part of the reason change is so hard.

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits', distils the results of hundreds of studies containing thousands of participants, to give you a blueprint for how to create new habits and tackle bad ones, whatever they are, and how to make it automatic so that willpower is no longer an issue.

→ You can dip into the first chapter, or check it out on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

January 23, 2013

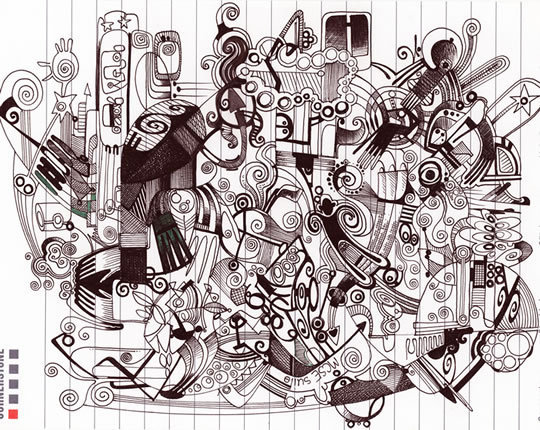

Can Doodling Improve Memory and Concentration?

All sorts of claims have been made for the power of doodling: from it being an entertaining or relaxing activity, right through to it aiding creativity, or even that you can read people's personalities in their doodles.

The idea that doodling provides a window to the soul is probably wrong. It can seem intuitively attractive but it falls into the same category as graphology: it's a pseudoscience (psychologists have found no connection between personality and handwriting).

Although it's probably a waste of time trying to interpret a doodle, could the act of doodling itself still be a beneficial habit for attention and memory in certain circumstances?

To test this out Professor Jackie Andrade at the University of Plymouth had forty participants listen to a mock answerphone message which was purportedly about an upcoming party (Andrade, 2009). People were asked to listen to the message and write down the names of all the people who could come to the party, while ignoring the people who couldn't come.

Crucially, these participants were pretty bored. They'd just finished another boring study, were sitting in a boring room and the person's voice in the message was monotone. The question is: even though the task is pretty simple, would they be able to concentrate long enough to note down the right names?

Here's the experimental manipulation. Half the participants were told to fill in the little squares and circles on a piece of paper while writing down the names. The rest just listened to the message, only writing down the names.

Doodlers' memories 30% better

Looking at the results the beneficial effects of doodling are right there. Non-doodlers wrote down an average of seven of the eight target names. But the doodlers wrote down an average of almost all eight names.

It wasn't just their attention that was enhanced, though, doodling also benefited memory. Afterwards participants were given a surprise memory test, after being specifically told they didn't have to remember anything. Once again doodlers performed better, in fact almost 30% better.

So perhaps if you're stuck in a boring meeting or someone is droning on at you about something incredibly uninteresting, doodling can help you maintain enough focus to pull out the salient facts.

The mind on idle

But why does it work? We can't tell from this study but Andrade speculates that doodling helps people concentrate because it stops their minds wandering but doesn't (in this case) interfere with the primary task of listening.

When people are bored or doing a simple task, their minds naturally wander. We might think about our weekend plans, that embarrassing slip in the street earlier or what's for supper.

Perhaps doodling, then, keeps us sufficiently engaged with the moment to pay attention to simple pieces of information. It's like keeping the car idling rather than turning it off. On idle we're still paying some attention to our surroundings rather than totally zoning out.

Obviously doodling is not a task you want to indulge in while concentrating on a complicated task, but it may help you maintain just enough focus during a relatively simple, boring task, that you can actually get it done better.

Research on doodling might sound a little trivial but it's fascinating because it speaks to us about many facets of human psychology, including mind wandering, zoning out, attention and the nature of boredom. Plus it's a really nice idea that doodling has a higher purpose, other than just wasting time and paper.

• Have you read my new book 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits'? Would you mind reviewing it on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk? Your honest opinion will help others decide. Thank you.

Image credit: Filippo C

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

About 50% of our everyday lives are habitual, according to some research. That means that, while we're awake, about half the time we are repeating the same actions or thoughts in the same contexts.

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits', distils the results of hundreds of studies containing thousands of participants, to give you a blueprint for how to create a new habit, whatever it is, and how to make it automatic so that willpower is no longer an issue.

January 21, 2013

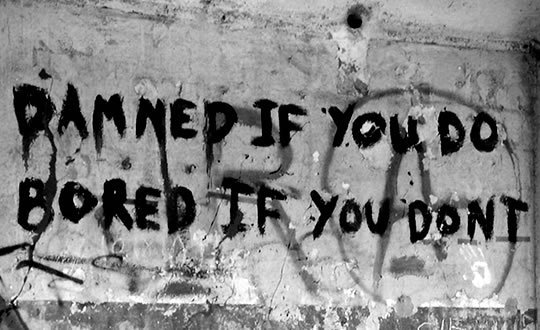

Boredom Explained (in under 300 words)

There are these weird people who never seem to get bored.

"Oh!" say the chronically interested and engaged, "What a fascinating and exciting world we live in. How wonderful it is to be alive. How can anyone possibly be bored with all the variety in life?"

Lucky you.

I'm with French philosopher Albert Camus, who said (in The Plague):

"The truth is that everyone is bored, and devotes himself to cultivating habits."

'Everyone' might be a slight exaggeration, although some estimates suggest up to 50% of us often feel bored. For teenagers that's definitely an underestimate.

And boredom is not to be taken lightly. There's evidence that those who are bored are more likely to die earlier than others (Britton & Shipley, 2010). Also, bored airline pilots make more mistakes as do bored nuclear military personnel. So you really can be bored to death.

Here's how psychologists describe the experience of boredom (Eastwood et al., 2012):

Frustrated: being unable to engage with a satisfying and interesting activity and finding this really frustrating.

Meaningless: everything seems meaningless. Boredom is an existential crisis: you want to shout, "What is the bloody point?"

Boring environment: feeling that everything and everyone around us is boring.

And here are the three psychological strategies that people spontaneously use to cope with boredom (Nett et al., 2009):

Reappraise: mentally work to increase the value or importance of the situation or activity.

Criticise: change the situation to dispel the boredom.

Evade: distraction with another activity.

Of course we use all of these strategies at different times. But there's tentative evidence to suggest that we should rely more on reappraisal than the other two. The worst strategy seems to be trying to evade boredom (think: drink, drugs and gambling).

Image credit: Cassidy Curtis

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits: How to Make Changes that Stick' is now available on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk, and at all good retailers.

January 14, 2013

Can You Be Addicted to Facebook or is it Just a Bad Habit?

From my new book:

"We don't know her name, but her problem illustrates a new fear. According to a short case report in an academic journal, a 24-year-old woman presented herself to a psychiatric clinic in Athens, Greece. She had joined Facebook eight months previously, and since then, her life had taken a nosedive. She told doctors she had 400 online friends and spend five hours a day on her Facebook page. She recently lost her job as a waitress because she kept sneaking out to visit a nearby Internet cafe. She wasn't sleeping properly and was feeling anxious. As though to underline the problem, during the clinical interview she took out her mobile phone and tried to check her Facebook page."

It seems we live in an age of paranoia about what the Internet is doing to our minds. Inspired by this, some psychologists are now creating scales designed to measure whether the Facebook habit is getting out of control.

One of these asks you to answer the following questions on a scale running through very rarely, rarely, sometimes, often, up to very often (Andreassen, 2012). Note that you should decide how often these have happened during the last year:

Spent a lot of time thinking about Facebook or planned use of Facebook?

Used Facebook in order to forget about personal problems?

Felt an urge to use Facebook more and more?

Become restless or troubled if you have been prohibited from using Facebook?

Used Facebook so much that it has had a negative impact on your job/studies?

Tried to cut down on the use of Facebook without success?

According to the author, if the answers are either 'often' or 'very often' to at least four of these six questions, then the Facebook habit may well be getting out of control.

This is described as a 'Facebook Addiction Scale', but can you really be addicted to Facebook? It's debatable and I've discussed this before (see: Does Internet Use Lead to Addiction, Loneliness, Depression…and Syphilis?). Technically, probably not because Facebook gathers together all kinds of activities, like gaming and social networking, and these need to be tested individually (Griffiths, 2012).

That said, some aspects of Facebook use (likely the social networking) do certainly come to rule some people's behaviour, such that it starts to interfere with their everyday lives.

Bad habit or addiction?

Although I'm a little skeptical about the scale, you can use it to check up on whether any of your habits, not just Facebook, are getting out of control. Try replacing 'Facebook' in the questions with any other routine. This is a good informal way of working out if a target routine behaviour might be slipping over into the danger zone.

There is certainly a lot of crossover between bad habits and addiction. For comparison, here is what we classically think of as an addiction:

They dominate thoughts and behaviour,

They change the way we feel,

You need more of them to get the same initial effect,

You suffer withdrawal when they are reduced or removed,

They conflict with our everyday responsibilities, whether at work or socially.

After abstinence, the pattern of behaviour reasserts itself.

When you look at this you can see why the confusion about whether some behaviours are addictions has arisen. Suddenly even very benign behaviours like reading, watching TV or, indeed Facebook use, can start to look like addictions.

It's important to remember that we're talking about a sliding scale here. It's only at the top end, when these behaviour are seriously interfering people's lives that habits become pathological.

Image credit: nate bolt

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits: How to Make Changes that Stick' is now available on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk, and at all good retailers.

January 10, 2013

How to Stop Biting Your Nails

The bad habit of nail-biting is much more common than you might think.

Some studies have found about one-quarter of children bite their nails habitually (Ghanizadeh & Shekoohi, 2011), others say it may peak at almost 45% in adolescence (Peterson et al., 1994).

More surprisingly, the prevalence amongst adults may be just as high, with some estimates at 50% (Hansen et al., 1990). I had no idea it was potentially that high—I guess it's a habit that people hide well from others.

Nail-biting is certainly something that has emerged as a hot topic as I've been speaking to people about my new book. As I don't specifically cover it there, although the general techniques I describe are applicable, here's my 8-step guide based on the psychological research available:

1. Seems obvious, but you've got to want it

It might seem redundant to say, but any change has to be desired, really desired. And for such a simple behaviour, nail-biting is surprisingly hard to quit, perhaps partly because it doesn't seem that big a deal and our hands are always with us. This is especially a problem if you are trying to change someone else's behaviour.

One method for boosting motivation is to think carefully about the positive aspects of changing the habit, for example attractive looking nails and a sense of accomplishment.

Also, make the negative aspects of nail-biting as dramatic as possible in your mind. If you tend to think it's no big deal then you're unlikely to make the change.

In addition, you can try mental contrasting, which has been backed by psychological research.

2. Do not suppress

It doesn't matter if it's you or your child that you're trying to change, suppression does not work. Punishing a child for this 'bad habit' is a bad move. They will know it's a way to attract attention and they will use it.

The same is true when changing your own habit. Trying to tell your unconscious to stop doing something is like trying to tell a child. It reacts childishly by doing the complete opposite. Here's the technical explanation for why thought suppression is counter-productive.

3. Instead replace bad with good (or at least neutral)

One of the keys to habit change is developing a new, good (or at least neutral) response that can compete with the old, bad habit. The best types are ones that are incompatible with your old habit.

So, for nail-biting you could try:

chewing gum,

putting your hands in your pockets,

twiddling your thumbs,

playing with a ball or an elastic band,

clasping your hands together,

eating a carrot,

or clipping or filing them instead.

4. Use visual reminders

If you keep your nails clipped short then there is less temptation to bite them. Some people recommend having a manicure because the money spent, along with how much better your nails look, will deter you from biting them.

You could also paint your nails a bright colour as a reminder, although most men seem to find this look difficult to pull off—I can't imagine why.

Another method is to wear something around your wrist, like a bracelet or elastic band, to remind you of your goal. Remember that habits live in the unconscious so you bite your nails automatically. Visual cues are a way of reminding you of the change you want to make.

Research has even shown that a wristband that is difficult to remove can be helpful (Koritzy & Yechiam, 2011).

5. Notice the situations

Habits are heavily bound up with situations.

Unfortunately it can be difficult to spot habits because they are performed unconsciously. However you may spot particular times during the day when the habit occurs, like while watching TV.

If you can bear it, enlist those around you to help point out when you are performing your bad habit.

Painting your fingernails with that nasty tasting fluid can help pull you out of autopilot and alert you to situations in which the habit is performed. But it probably won't work on its own. Some people even say they get to like, or at least tolerate, the taste!

6. Notice associated thoughts and feelings

Just like situations, our thoughts and feelings cue up our behaviour. If you can spot the types of things you are thinking about or feeling when you bite your nails then this can help. Some people like to use mindfulness as a way of increasing self-awareness.

When you notice the thoughts coming (for example, anxiety) you can prepare your alternative response (for example, getting the worry beads out of your pocket).

7. Repeat the competing response

Your new replacement habit will build with repetition, but at first it will have to compete with your old habit. Try to avoid beating yourself up for slip-ups, as they are bound to happen. It's a gradual process. (See: The Surprising Motivational Power of Self-Compassion)

8. Keep up the good work

Keeping the new response going can be hard. One method to make your progress more obvious to yourself is to take pictures of your nails on your phone every few days (Craig, 2010). When you see how far you've come (or, alternately how little progress has been achieved), this should help push you on.

Remember that old habits do not die; they lie in the unconscious waiting to be reactivated. Go easy on yourself if you slip-up, but remember that a lot of the battle with bad habits is about self-awareness.

What about the deeper psychological issues?

People often wonder if nail-biting is a symptom of a deeper problem. Perhaps if that deeper problem were fixed, the nail-biting would go away on its own?

Opinion is divided on whether this is true. Counter-intuitively, there is no strong evidence that nail-biting is related to anxiety. Worse, it's very difficult, if not impossible, to probe the unconscious for the reasons for our behaviours (yes, that's why they call it the unconscious!). (Also see: the hidden workings of the mind)

Most, though, agree that whatever the cause, the learned habit needs to be targeted. So start with these approaches and see how it goes. If it's not working, try making small tweaks, like using a different replacement habit, and then have another go.

Image credit: myklsc

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits: How to Make Changes that Stick' is now available on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk, and at all good retailers.

January 7, 2013

Get the First Chapter of ‘Making Habits, Breaking Habits’ for Free

Say you want to go to the gym regularly, eat more fruit, learn a new language, make new friends, practice a musical instrument, or achieve anything that requires regular application of effort over time. How long should it take before it becomes a part of your routine rather than something you have to force yourself to do?

I looked for an answer the same way most people do nowadays: I asked Google. This search suggested the answer was clear-cut. Most top results made reference to a magic figure of 21 days. These websites maintained that "research" (and the scare-quotes are fully justified) had found that if you repeated a behavior every day for 21 days, then you would have established a brand-new habit. There wasn’t much discussion of what type of behavior it was or the circumstances you had to repeat it in, just this figure of 21 days. Exercise, smoking, writing a diary, or turning cartwheels; you name it, 21 days is the answer. In addition, many authors recommend that it’s crucial to maintain a chain of 21 days without breaking it. But where does this number come from? Since I’m a psychologist with research training, I’m used to seeing references that would support a bold statement like this. There were none.

My search turned to the library. There, I discovered a variety of stories going around about the source of the number...

→ Now click here to read the first chapter for FREE (PDF format).

~~~~~~

Kindle owners: If you would like the first chapter delivered to your Kindle device then visit Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk and click 'send sample now'. It will be sent to you for free.

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits: How to Make Changes that Stick' is now available on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk, and at all good retailers.

December 31, 2012

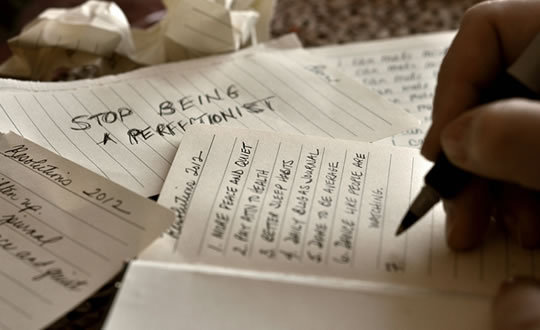

10 Step Guide for Making Your New Year’s Resolutions

One of the main reasons that New Year's resolutions are so often forgotten before January is out is that they frequently require habit change.

And habits, without the right techniques, are highly resistant to change, as I explain in my new book 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits'.

But because habits work unconsciously and automatically, we can tap into our in-built autopilot to get the changes we want.

So here is my quick ten-step guide to making those New Year's resolutions, based on the hundreds of psychology studies I cover in the book.

1. For big results, think small

The classic mistake people make when choosing their New Year's resolutions is to bite off more than they can chew. Even with the help of psychologists, people find it hard to make relatively modest changes. So pick something you have a reasonable chance of achieving. You can always run the process again for another habit once the first is running smoothly.

2. Mental contrasting

Choosing what to change about yourself and sticking to it isn't easy. There is a method you can use, though, to help sort the good ideas from the bad, and to help boost your commitment.

Mental contrasting is described in more detail here but in essence it's about contrasting the positive aspects of your change with the barriers and difficulties you'll face. This helps you to be more realistic about what is possible.

Research has found that following this procedure makes people more likely to give up on plans that are unrealistic but also commit more strongly to plans they can do.

3. Make a very specific 'if-then' plan

The types of plans for change people make spontaneously are vague: things like: "I will be a better person" or "This year I'll get fit".

These are fine as overall aims but it's much better to make really specific plans that link situations with actions. For example, you might say to yourself: "If I feel hungry between meals, then I will eat an apple." When repeated these types of actions will help you achieve your overall goals.

I talk more in my book about how to make these types of plans. The details are really important.

4. Repeat

Habits build up by repeating the same action in the same situation. Each time you repeat it, the habit gets stronger. The stronger it gets, the more likely you are to perform it without having to consciously will it.

So, how long will the habit take to form? Well, it depends on both the habit you've chosen and your personality. The idea that it's always 21 days is demonstrably wrong.

5. Tweak

Everyone is different, so what works for one person might not work for another. Habit change is no different. If your very specific plan seems to be going wrong after a while, or doesn't feel right, then it may need a tweak. Try a different time of the day or performing the habit in a different way.

Habit change needs self-experimentation. Are there any tweaks to your environment you can make? Those trying to change eating habits might try buying smaller plates, putting fruit on the counter and avoiding TV dinners.

6. Don't suppress...

An odd thing happens when we try to suppress thoughts: they come back stronger. It turns out that thought suppression is counter-productive. The same with habits: if you try to push the thought of cake out of your mind, suddenly it will be everywhere.

7. ...instead replace

Habits cannot be killed off. It's like the old saying that you never forget how to ride a bike. Old habits are lying there in the back of your mind waiting to be cued off by familiar situations.

It's much better to plan a new good habit to replace the bad old one. Try to learn a new response to a familiar old cue. For example, if worrying makes you bite your nails, then, when you worry, do something else with your hands, like making a hot drink, or doodling.

8. Shield yourself

There's bound to be some competition between old and new habits at first. This is normal. Try to notice or anticipate what the mental danger points will be and plan for them.

For example, you may want to get up earlier but know that you'll feel lazy when you wake up. Plan to think about something that will make you jump out of bed, like an activity you are looking forward to doing that day.

9. Pre-commit

We're most likely to give in to old habits when we're tired, low and hungry. So pre-commit to your new habit when your self-control is strong.

For example, clear all the unhealthy food and drink out of the house, cut up the credit card or give the gaming controller to a friend for safe-keeping. Getting in the habit of planning ahead is one of the best ways of keeping your New Year's resolutions.

10. Self-affirmation

Another trick to boost your self-control in the moment is to use self-affirmation. This involves simply thinking about something that is important to you, like your friends, family or a higher ideal. Studies suggest this can boost depleted willpower, even when your ideas aren't connected to the habit you are trying to ingrain.

The habit of habit change

Once you've successfully ingrained a modest new habit, it's time to go back to square one, choose a new habit to work on and start again.

This is the best, most sustainable path to self re-invention—forget about waking up tomorrow a totally different person. Instead go little-by-little, step-by-step, and eventually you will get there.

Forget all that haring around, be the tortoise.

Image credit: Flood G

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits: How to Make Changes that Stick' is now available on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk, and at all good retailers.

December 18, 2012

PsyBlog’s 10 Most Popular Psychological Insights From 2012

Here's my review of the psychological insights covered here on PsyBlog in 2012 that have proved most popular with you, the readers.

1. How the mind works

Never let it be said that the titles for my articles lack ambition! Here we dipped our toes into 10 counterintuitive psychology studies, the findings from which help show that psychology is much more than just common sense.

Insights included the fact that suppressing your thoughts is counter-productive, brainstorming doesn't work and hallucinations are more common than you'd think.

2. How to be a great leader

Six factors seem to set apart the truly great leaders from the rest: decisiveness, competence, integrity, vision, persistence and, perhaps most surprisingly: modesty.

We could really do with some more modest leaders, don't you think?

3. The dark side of creativity

Creativity is always a favourite topic here on PsyBlog but usually we're talking about the positive aspects. Like most things in life, though, creativity has two sides.

In fact research suggests that creative individuals are also more likely to be arrogant, good liars, distrustful, dishonest and maybe just a little crazy—OK, let's say eccentric.

Yes, we need all those creative people or the world would be a much more boring place, but take heed and watch out: they're dangerous!

4. Why the incompetent don't know they're incompetent

While our thoughts are on darker matters, here's a quote from Bertrand Russell:

"One of the painful things about our time is that those who feel certainty are stupid, and those with any imagination and understanding are filled with doubt and indecision."

The simple reason is that the incompetent don't learn from their mistakes. Even telling them seems to make little difference. Unfortunately talented people also tend to underestimate their brilliance. Could this partly be why society doesn't change?

5. Psychological distance: 10 effects of a simple mind hack

To cheer you up after that, here's a neat, multi-purpose mind hack.

Imagine you're suddenly in another country, thousands of miles away. This is one way of achieving psychological distance, which has all sorts of neat effects.

Evidence from studies in the last few years has shown that this can help challenging tasks seem easier, generate self-insight, increase persuasiveness, increase emotional control and much more.

6. Why do people yawn?

It seems like a simple question, but why do people yawn? It turns out that it isn't just because of boredom or tiredness, but it may also be a social signal or possibly a way of cooling down the brain.

Whatever it is, the best way to stop a chronic attack of yawning is to put a cold cloth on your forehead and breathe through your nose.

(I don't recommend doing this in a meeting, though, even if it is really, really boring.)

7. How to defeat persistent unwanted thoughts

As we found out earlier in the year, trying to suppress thoughts tends to make them come back stronger. So, what can you do when plagued by thoughts that just won't go away? Some suggestions on how to defeat persistent unwanted thoughts came from expert on the subject, Professor Daniel Wegner.

They included focused distraction, thought postponement, paradoxical therapy, meditation and writing about it. Some are relatively new techniques, but all are likely to beat the most natural response of trying to push unwanted thoughts out of mind.

8. Memory enhanced by a simple break after reading

I really like this study that found that a 10-minute break after reading enhanced recall 7 days later.

It corroborates my own perception that I remember books better which I've read on trains, perhaps because I pause more often to contemplate the view, so enhancing the memory.

9. How memory works

Inspired by the short article on taking a break after reading, I dug up more fascinating facts about how memory works. This culminated in one of my personal favourites of the year.

In 'How Memory Works: 10 Things Most People Get Wrong', I covered some of the vital but less-known facts about memory. These include that forgetting helps you learn, recalling memories alters them and that learning depends heavily on context. Most controversially of all, though: memory does not decay.

10. Making Habits, Breaking Habits

Bit of cheat now because this article comes from 2009: how long does it take to form a habit? But, it was the wonderful response by you to this article 3 years ago which sparked off a journey that led to my new book: 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits: How to Make Changes that Stick'.

It looks at how habits work, why they are so hard to change, and how to break bad old cycles and develop new healthy, creative, happy habits. Some of the answers, I think, will surprise you. As ever here, the book is based on findings from psychological science.

It's available now on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk and at all good retailers.

Image credit: Corie Howell

Making Habits, Breaking Habits

My new book, 'Making Habits, Breaking Habits: How to Make Changes that Stick' is now available on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk, and at all good retailers.

Jeremy Dean's Blog

- Jeremy Dean's profile

- 29 followers