Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 527

July 15, 2012

Madala Kunene for all seasons

Guest Post by Deon-Simphiwe Skade

Last Saturday, Cape Town was furiously cold. The weatherman has predicted a wet cold front that may last well over a week. Naturally, the spirits of most people are low, except for those who are braving the winter chill in search of some entertainment. I’m part of this lot, but feel that my motivation to be out in the night is more meaningful. For quite a long time I had been hoping to witness the legendary Madala Kunene perform live. And now that wish is about to come true, thanks to the organisers of the musical extravaganza simply known as the City Hall Sessions. Saturday’s bill (also featuring Caiphus Semenya) marks the end of what has been a three-day series of performance that saw the likes of Mxo, Errol Dyers and Khaya Mahlangu among others, take the stage.

The turnout is very good. Both the reserved and unreserved audience spots are filled up by warmly dressed patrons. They are cheerful, expecting a marvellous time ahead. Then comes the first sound. It seeps from a synthesizer and the notes sound like a prelude to something momentous. What follows is a belching rumble of Sibusiso Mdaweni’s electric bass. It’s easy to see why Mdaweni has been Kunene’s long time collaborator. The control he exercises over the tempered sound of the bass strings is admirable. He’s tactful, confident yet unassuming. He doesn’t wriggle his body like some over-conscious instrumentalists do when they take centre stage. He just keeps a calm demeanour that makes him a true ‘Mr Cool’.

At first, Kunene’s guitar strumming appears to be hesitant. But that seems to be deliberate. It’s clear that the maestro is assessing the mood and the temperance of the music that has already taken a firm position on stage. No part of any sound ingredient should overwhelm another. Everything should be blended into a perfect harmony. Three men throw the weight of their voices behind the song, singing briefly in isiZulu in what seems to be a refrain. But their voices are muffled and submerged below everything audible. Kunene notices the sunken voices and wears a smile. He has a graceful grin that inspires calm and hope. Perhaps this is due to his ever humble demeanour, despite being enormously gifted and seemingly oblivious to all of it. Sadly, the singing ends before there’s any improvement in the sound quality. At this stage, I can only pin my hope on the engineer, his alertness – he must have detected the flaw in the sound.

Kunene and his band continue, filling the vast space of the city hall with magic. Cheers erupt from the audience, they are happy with the start. All should go well now. The song plays on for a while, until the horns add their voices to the music too. The sound that comes out rekindles memories of great African horn players like Mankunku Ngozi and Hugh Masekela.

When the first song ends, Kunene takes a moment to speak. He starts off by greeting the crowd in isiZulu. A mild echo comes from the speakers and now I get really worried. But Kunene goes on to introduce the next song, and the music resumes right away. It’s clear now that the sound glitch comes from the voice microphones. The signature guitar sound rises, this time on its own. It’s soon joined by the sound of percussions that rattle and hiss in a coordinated fashion. Mdaweni lends his bass to the mix. The crowd cheers again and in the background a trance-like jam swells elegantly. The horns sound and are joined by the drums and the keys. The music prompts people to move, dance and whistle whichever way they can. Kunene’s voice now loud and clear.

Kunene is widely referred to as an eclectic musician by the followers of his music. This is not an off-the-mark reference, knowing that the musician is blessed with admirable musical prowess and vision. Even in its near-fitting description, ‘eclectic’ does not flaunt the fact that much of Kunene’s music is overwhelmingly progressive. This brand of music, which he simply calls Madala-line defies titles that people put on it. The long list of creative collaborators he has worked with shows just how desirable and wealthy his music is. Among those who shared in his wealth are Mabi Thobejane, Busi Mhlongo and Syd Kitchen to name but a few.

Kunene’s repertoire for the City Hall Sessions is a reflection of various artistic planes he has traversed. These journeys share valuable secrets about the myriad of the compositional structure and aspirations his music has; his unconventional guitar tuning being one example. Kunene’s compositions don’t necessarily have a benchmark to conform to, but instead reveal the continuous state of transcendence his music takes. There’s jazz and everything musical in the songs, established innovations or those still lurking somewhere in space waiting to be discovered, which is what Kunene does very well through melodies layered with rich musical flavours.

The band plays ‘Gumbela’, a trance-like gem lead by Kunene’s mouth harp. They play ‘Impukane’, a piece lifted from Madamax, a collaborative effort done with the Swiss-born guitarist Max Lasser. The version of ‘Impukane’ the band plays is mellowed. But it’s still the same jewel, only made fresher by the new approach. That vital string from Kunene is still there, leading the musical procession gracefully. Lungiswa Plaatjies, whose voice appears on the record version, is not here and I fear it may not sound as great. I’m mistaken. The three gentlemen doing backing vocals are on point – they give the live version a mysterious edge.

“Tshelani uBongani atshele uBonginkosi ukuthi amakhosi ayabonga” is a song that brings out Kunene’s mournful and nonchalant singing he is renowned for. But before that, his strings render a devastating solo – the keys are equally overwhelming. ‘Gongo’ follows, before the last song pulls down the curtain.

Kunene thanks the audience and the organisers for the support. He urges the audience to continue throwing their weight behind initiatives like the City Hall Sessions. From this remark I remember the sad marginalisation of South African legendary musicians by the very institutions that should immortalise them through acknowledging and celebrating their creations. Kunene’s appreciation for the support received feels like a lament towards the gatekeepers who control which artists or genre of music should be marketed more than others. His gratitude, as heartfelt and sincere as it is, feels like an unintentional subtext woven into his last words. I say this mainly due to the proverbial lack of indigenous music on the local broadcasting platforms. Radio stations across South Africa, particularly those like uMhlobo Wenene, Lesedi FM and others, are not doing much in helping to spread the reach of our music of legends. Instead, they dedicate the bulk of their playlist to western music, particularly American genres, with little compensation given to the local musicians by playing pop songs that only aspire to be American.

One wonders how the wisdom of our cultural icons like Kunene and many others would be passed on to future generations if these conditions continue unabated. Sadly, some of the fallen icons departed not having been acknowledged as sages of our time despite their pivotal contribution to music and culture. That said, bureaucracy or not, nothing will dissolve the love deeply felt for Madala Kunene in the city hall. The jackets are off now; it appears that the season has taken a cheerful turn.

* Deon-Simphiwe Skade blogs over at Acoustic Strings. Pictures by Jonx Pillemer.

July 13, 2012

Friday Bonus Music Break

Above is how people keep warm in Johannesburg winters. And below is what you hope to bounce to during long summer nights.

Southeast from Johannesburg. Music video made in Durban. Band’s from Durban. And they’re named after Durban:

Okayafrica tipped us off about the video for Nigerian Ajebutter22 (yeah…). Clubby:

Gazza’s ‘Friday Special’ (the song; turn down the bass a bit — quality’s grainy):

Elliot ran into revoluçionista rapper Azagaia eating prawns in Maputo this week. Here he is with ‘Minha Geração’:

Haven’t heard Mikko–admittedly, in his spare time 1/3rd of Chuck D’s Planet Earth Planet Rap program–as excited about a new release as over the past days. Must be the return of Public Enemy:

Two from Kenya. Xtatic…

…and Rabbit’s ‘Swahili Shakespeare’ (in a slower mode):

To wrap up the week: I didn’t know about Malian Sibiri Samaké until top music blog Tropicalidad (one day they’ll drop the “world music” tag) mentioned him this week. This recording in Studio Bogolan is exceptional:

Tutu’s Board Games

Shameless self-promotion. “Board Games” is a short documentary video I did for my friend Kent Lingeveldt who runs the independent Alpha Longboards company. I just showed up at his workshop when he told me to, followed him where he told me to, and drank coffee when he told me to. The video is “a day in the life”–or “a few days in the life”–of Alpha Longboards, and of Kent himself. Kent is something of a veteran and an enigma in the Cape Town skating scene, and was one of the first longboarders on the Cape Flats. The aim was to explain what made Alpha different to other board companies; they use local wood, every board is shaped and carved by hand, and every piece of artwork is unique. Also, how many other longboard companies have Desmond Tutu as a patron?

Dakar Fashion Week

Guest Post by Tanya Bindra

Last May, Vogue Italia devoted their entire issue to Africa and called it “Rebranding Africa”. Naturally, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon was on the cover. The issue details the Vogue expedition into Africa, with editor-in-chief Franca Sozzani pleading with Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan to build an “African Rodeo Drive”, and gallantly emerging with development statistics, trend reports and photo spreads that purposefully did not include anything “sad, trashy or poor”.

If the articles read like NGO-funded, feel-good “development” stories that make you half-expect a request for donations in the envelope enclosed, it might be because Sozzani has been appointed as a Goodwill Ambassador for Fashion4Development — a UN initiative intended to ‘help’ Africa.

The Vogue Italia issue is just one example of the pervasive patronizing frameworks underlying the sudden discovery of fashion and hence, ‘modernity’, on the continent. Even journalists seem to surprise themselves when, as the New York Times put it, “Africa is in the news — but not just for the sad and familiar reasons of conflict and suffering.”

But who is rebranding Africa really? And for what purpose? How much does the shift towards “positivity”, as Sozzani refers to it, actually accomplish if the main narrative still offers Africa as a continent to consume, save or exploit? Most importantly, do the tokenizing special issues really only work to allow the industry to exclude and marginalize African professionals from the fashion arena?

Indeed, a close look at the fashion industry today reveals much more than just the latest trends. In fashion and fashion media, binaries — like the local and the global, the modern and the traditional, the civilized and the barbaric — are constantly being constructed, fastened and reified.

As designers continue to release fantasy collections inspired by their latest trip to exotic, mystical and faraway lands (Michael Kors, Giorgio Armani) and fashion editorials feature white models amidst backgrounds of hyper-sexualized dark bodies in seemingly equally dark continents (Daria Werbowy for Interview Magazine), it is clear that for the fashion world, Africa represents a sort of otherness. That otherness, and especially the sexuality of the other, is marketed as flavor and spice, something new, sexually raw and stimulating. Whether depicted in high-fashion advertisements or on the runway, racial difference becomes both at once threateningly pleasurable and seductively dangerous, positioning it at the intersection of most intimate obsessions with desire and death.

The commodification of difference — with its relation to the primitive — also necessitates a sense of moral duty to conquer and civilize with law and refinement. The mechanisms of exotifying and eroticizing difference operating through discourses of fashion, travel, leisure, and style deeply effect the ways in which those part of the dominant cultures consume, whether they are sex tourists or suburban mall fashionistas.

Despite the fact that there are still hardly any people of color designers, buyers, stylists, models or organizers in the mainstream fashion industry, the catwalk essentialism continues, as do the one-time, one-issue only ‘development’ features on African or otherwise ‘ethnic’ fashion. But hey, at least blackface doesn’t happen anymore, right? Oh, wait.

Ten years ago, Senegalese designer Adama Paris created Dakar Fashion Week in an effort to highlight local designs and celebrate Senegalese fashion, art, and self-expression. Although its beginnings were humble, it has now become a major platform for Senegalese and other international designers to showcase their talents. This year featured designers from over 15 countries including Morocco, Pakistan, Haiti, Mali, Egypt and Ivory Coast, and was made open to the public.

I spoke to Adama Paris (née Adama Amanda Ndiaye), about her opinion on the representation of African designs and designers in the fashion industry.

Why did you start Dakar Fashion Week?

I wanted to create a platform for African designers that wanted to show their work in Africa and to showcase their designs to African buyers and viewers. During the past 10 years, it’s been getting bigger and better. We’re getting lots of interest from designers all over the continent, which is great. We’re aiming to be a big fashion week like Paris or London – to really be able to showcase any designer who wants to sell and show their designs in Africa.

You mentioned that designers sometimes have difficulty in finding local and international markets to distribute their creations.

Yes, it’s getting better but really slowly. It definitely affects designers’ work. If you spend months to create a collection and you’re not able to sell it afterwards…it’s really the worst thing that can happen to a designer. We’re doing it first for the fashion but we’re also doing it because it’s our job. I don’t do anything else. I’m a designer. It’s not like I design on the side and I work in the bank. If you can’t pay your rent doing whatever you do, it’s really hard.

I don’t think it’s affecting the creativity of the designers but I think it’s changing the pace of creation. If you have money or someone that’s buying your stuff, you can make a lot, but if you don’t have that much, you can’t even make two collections a year. So of course it affects us a lot.

In addition to creating Dakar Fashion Week to support designers and the African fashion industry at large, you also introduced the first Black Fashion Week last year in Prague. While it’s primarily an effort to represent black designers and the diaspora, it also features black models at a time when the majority of models used in the largest fashion weeks around the world are still white. I think some 90% of the models used in last year’s New York Fashion week were white.

It’s more. It’s 6% non-Caucasian models. So that 6% is made up of Africans, Asians, anybody not white…not only black people. So yes, the fashion industry is white.

And those are just the models.

Everybody is white in this industry…the designers, the buyers, the audience. And it’s just weird because you have the feeling in fashion that we’re so open. And we’re not. We’re definitely not. That’s why I thought about having a show that can showcase minorities. Of course when I first started to go see sponsors and partners, they were like oh yeah Black Fashion Week is really communitarian, like we just want to stay within ourselves. But that’s not actually the meaning of Black Fashion Week. We wanted to showcase black designers, not necessarily African — but anyway it’s not only about the color. We also had white people from South Africa.

I want them to be part of a black movement that can showcase black or African designers that don’t have the opportunity to show in the big fashion weeks, Paris or London or elsewhere. How many black designers are there in Paris Fashion Week? None. And New York is the same. London is the same. So those people who said to me, “Oh well why not create a White Fashion Week if you’re going to have a Black Fashion Week”…well, we don’t need a White Fashion Week because it’s already white. If we’re naming ourselves Black Fashion Week it’s because there’s a real need for it, it’s not just because we want to throw a show. It’s much more than a show, it about educating people on what black fashion is.

You read that crap in Vogue Italia. That proves that we don’t have very many journalists specializing in black fashion. Another girl can write on Michelle Obama and call that black fashion…because now black fashion means black bourgeoisie fashion? That’s nonsense. So I wanted to create Black Fashion Week to work against those systems that categorize black fashion as only one thing, especially in Europe where there is a lack of black fashion. Whatever is done in the fashion industry and termed as “ethnic” or “black” is done by white people.

That reminds me of the Vogue Italia “black” issue published a few years back, by the same Sozzani, which presumably was also edited and conceived of by white people. The industry’s fascination with “ethnic fashion” also brings to mind the countless advertisements that market “ethnicity” as a sort of sexual experience, intense and mysterious, yet also slightly barbaric and backwards.

Absolutely. I don’t like the name of “ethnic” fashion. It’s just degrading to me. We talked to several partners who wanted us to call the show “Ethnic Fashion Week” and asked us to change the name. I said no, it’s Black Fashion Week. It’s about much more than color, but it is important to name it.

It was difficult at first, but we found funding in Prague, which was cool. Now we’re going to do it in Paris, in October. We found a sponsor in Angola. So it means we have our place. When we do it in France, this will prove that we have a lot of black designers in France and we’re getting help from Africa to showcase our designs in Europe. So there’s a lot of people involved in this process and I’m glad we’ll get that sponsorship from Angola.

We’re also going to do it in Bahia, Brazil. They called me because they were impressed with what we did in Prague. After the show in Prague, which was not big, people realized the need to showcase our design outside of Africa. Especially since this is the year of Négritude, and Bahia is a black city in Brazil where all the minorities are, it’s great. They invited me for 10 days and we’re going to do 3 cities.

It seems like a great opportunity to celebrate the art of fashion, while making it more accessible by expanding dominant notions of beauty.

Exactly. To me it’s not just about business. I mean of course we want to sell. We invite buyers because we want to sell. But first it’s about our struggle. We’re always fighting to be recognized.

Are you seeing more interest in your designs abroad?

Oh yes, and it makes me smile because there are European designers who are now using wax in their designs, although we’ve been doing it for years and nobody took any interest in it. And in some ways it’s sad. I once saw designs in a magazine from Gwen Stefani and Burberry and next to it was another picture of a dress labeled “African designer”. They didn’t give any credit. It was just awful. But that’s the way the fashion industry in Europe works.

Any last comments?

I want to thank the press because honestly we’ve had lots of help from press, they stick out for us. Especially when I started out, I was small, and they were here. We have overseas press coming, Le Monde, BBC, so it’s cool to know that there is some interest.

And I’m really happy with where we’re standing now because people know that we’re not only doing it for fashion. I’m a woman of color and I’m sensitive and I do want to fight. Not because I’m black, but for entrepreneurs in Africa, because we need to develop these countries. And we women are a big part of what’s going on in the continent, so this is my part. I love fashion, that’s what I do. That’s why I come back here to Senegal, to help and support, to put Dakar in the spotlight. I think people need to give credit to African women. They’re strong and they stand really tall to pull up their countries and this continent.

* Tanya Bindra is a freelance documentary photographer currently based in Dakar, Senegal. She covers news for international media outlets and focuses on social issues in post-conflict areas. All photos are by Tanya. More below and on her website.

Utopia Unstuck: A review of Africa Utopia’s African Sci-Fi screening

Guest post by Evelyn Owen

Last week, I scuttled along to London’s Southbank Centre for the Africa Sci-Fi Screening, an event forming part of the month-long Africa Utopia season. Having failed to make it to Bristol in time to catch the event’s parent exhibition – Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction at the Arnolfini, I was curious to see what the combination of Africa and sci-fi might involve. There was a palpable buzz from the evening’s earlier book readings and talks, and the mood in the muggy Purcell Room was jovial.

Not for long. Exhibition co-curator Al Cameron gave a verbose preamble to increasingly audible sniggering, followed by a second, marginally less verbose introduction from artis Mark Aerial Waller. I wasn’t timing it, but I’d guess at least fifteen minutes elapsed before a film appeared on the screen, by which point several people had walked out. It wasn’t until after Waller’s film – Superpower - Dakar Chapter (2004), a deliberately amateurish short involving renegade Senegalese scientists, the Orion constellation and temporal disturbance – that panellist number three, design and fashion forecaster Cher Potter, finally got a look in, speaking pleasantly but somewhat tangentially about her work on future scenarios in her native South Africa.

Things improved significantly with the second short, Neïl Beloufa’s engagingly creepy Kempinski (2007). This is sci-fi at its most stripped down; opening with a man lurking in the dark amongst his cows, which seem to have become his sole companions. The film proceeds via a series of encounters with Malian men, who offer disarmingly touching present-tense visions of the future. During its most surreal moment, amid sinister beeping noises, the camera rests on a lab-coated man in dark glasses sitting in a dimly-lit room with a glowing, blank, flat-screen TV behind him. Suddenly, the film’s artifice – cameraman, artist, and constructed scenario – seems to crumble: we really are seeing the future.

Unfortunately, the future of this particular event was perhaps all too predictable, but nobody seemed to have foreseen it. After the high point of ‘Kempinski’, there followed further obscure and shambolic conversation from the panel, a downward spiral, which quickly accelerated once the discussion was opened to the floor for questions.

Oh, what a mistake. From the two audience members who managed to grab the mic before the event finished, the criticisms came thick and fast: disappointment at the event’s deceptively enticing title; disgust at the incompetent presentation and; incredulity at the lack of African filmmakers on the stage… the critique was unrelenting, and nothing the panel said seemed to make any difference. By the end, an irate woman was on her feet, aggressively asserting that she would be making a formal complaint, to the accompaniment of supportive grunts and claps from the back of the auditorium. I staggered outside sweaty and confused, full of questions.

Africa is a Country wrote about the exhibition here, and interviewed the two curators here, and clearly it worked better within a gallery context, where a counterpoint between various works reflected a thoughtful curating of the works, and allowed more time and space for the ideas on science fictions of Africa, and what that might mean, to develop.

At this event, this counterpoint was thrown out of balance. Part of the problem was undoubtedly the title which as the most vocal audience critic observed, was at best an oversight and at worst deliberately misleading. At an event called “Africa Sci-Fi Screening”, one could reasonably expect to see a series of films, but in a slot of just one hour, there was only time for two shorts of under 15 minutes each.

Arguably a bigger issue, however, was the nature of the interpretation itself, which was lacking in discernible substance beyond some musings on the ‘ethnographic gaze’. There were moments when I began to follow what was being said, but my ability to do so rested on many years spent yawning over cultural theory texts in dusty libraries. It seemed to me that there’s a time and a place for scholarly rumination, and a public stage in front of an increasingly restive crowd is most definitely not it.

Cameron and his co-curator Nav Haq have argued elsewhere that Africa-based sci-fi like ‘Kempinski’ redirects science fiction so that it “becomes not a projection of the narratives of dominion […] but rather a fissure in which new subjects can be seen and heard”. But this is not the kind of thing that can easily be conveyed to an audience rendered unreceptive and defensive by almost an hour of incomprehensible flannel. The “fissure” with its “new subjects” were evidently utterly invisible to the majority who, despite the West African settings and characters of both Beloufa and Waller’s films, saw nothing but European (and, it need hardly be said, white) approaches, attitudes and interests in something that they had been led to believe was going to be ‘African’.

And this is perhaps the crux of everything that went wrong on this difficult night for all concerned. Even if, with a bit of thought, most people can see that there’s probably something to be gained from an event attempting to ask thorny questions about what ‘Africa’ might mean, and who and what can be ‘African’, in the heat of the moment, the urge to ‘showcase’ and to ‘celebrate’ can be uncontrollable. And, with a festival called ‘Africa Utopia’ as the backdrop, why should this be a surprise? Although the season does contain many exciting and potentially insightful highlights, I rather despair of the overall packaging, which recycles the old ‘see what Africa can offer the world!’ narrative.

It’s a tricky one. Do we really still need more cultural festivals wittering on about Africa’s sunny side? The Southbank Centre has already given us Africa Remix (2005) and now Africa Utopia – what next? Africa Epiphany? Perhaps London audiences are ready for something a bit more challenging. In fact, the word ‘utopia’ contains within it a well-documented pun: it derives from the Greek eu-topos, meaning ‘a good place’, but also from ou-topos, meaning ‘no place’. It’s a pity that this double meaning wasn’t drawn out more in the festival programme. As the vociferous crowd last week demonstrated, there’s a real hunger for meaty debate, for solid content and for new ideas. How to achieve this in a way that is intellectually stimulating, engaging and accessible is a question that I hope to see explored during the remainder of the festival.

* Evelyn Owen (@africanartldn) is a doctoral student in cultural geography at Queen Mary, University of London. She also writes the blog African Art in London.

July 12, 2012

John Terry’s Africa is an Alibi

We British like nothing more than a nice inquiry. The exorbitant jail terms meted out to last year’s rioters (whether actual or merely theoretical) are commonly supposed to have been a great disappointment to us all, a sad sign of a milksop rights-obsessed “democracy” that no longer has the stomach to chasten its miscreants with anything approaching the appropriate levels of severity. But while we longed to see young people birched on the BBC last summer, or else placed in the stocks outside Foot-Locker to be scorned by paying shoe-shoppers, still we struggled to summon up the same gusto for retribution when it turned out that our political and media elites have together made a corrupt and criminal class. For the politicians, editors and media moguls, it would be a very much more clubbable sort of inquiry.

“Brave” John Terry, the rugged football player who has twice been fired as captain of the English team, is currently foraging something of a middle way between those two forms of British justice. Terry is accused of racially abusing another player, Anton Ferdinand, and faces criminal charges that carry a maximum penalty of a (for him) piddling £2,500 fine. (Sam Wallace at the Independent has the best coverage of the trial on his twitter feed.)

Rivonia, it ain’t. The case seems likely to hinge on magistrate Howard Riddle’s opinion regarding the level of sarcasm with which Terry laced the phrase “fucking black cunt”. Terry maintains that only his subsequent description of Ferdinand as a “fucking knobhead” was meant in earnest.

The slow motion replays don’t look good for Terry in terms of establishing the legal question at hand (whether or not he committed a racially aggravated public-order offence) but his lawyers have chosen to take up much of the trial probing a deeper question: not whether Terry used racist language, but whether he is in fact a bona fide racist. They have sought to answer this question in the stupidest imaginable way.

Some of his friends and team-mates are black, the court has learned, and lots of them (including Ashley Cole, Salomon Kalou and Ramires) have never heard him profess anything racist before. None of Didier Drogba, Nicolas Anelka, Florent Malouda or John Obi Mikel provided affidavits. But José Mourinho did. He wrote a statement for the court about his former player being a nice guy and not a racist, which opened with the words: “I am José Mário dos Santos Mourinho Félix and I am manager of Real Madrid.” And who are we to doubt José?

But there’s more. Terry’s most compelling proof against his own racism turns out to be somewhere in Africa. In the statement he gave to police when they began to investigate the incident, Terry explained that he had supported charity work in Africa by his former team-mates Marcel Desailly and Didier Drogba. Evidently, Terry saw no need to specify what this charity work was, or where it took place (both Desailly and Drogba have worked on various philanthropic projects including the MDG-oriented 1GOAL Education for All and the Didier Drogba Foundation, which is mainly focused on healthcare in Ivory Coast and regularly holds glitzy fundraisers attended by John Terry at the Dorchester Hotel in London). But Terry also pointed out that as part of the England football team’s corporate responsibility exercises he had been involved in promoting the popular British charity Help for Heroes, a grant-making organisation that aims to provide assistance to British soldiers wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Said Terry: “My commitments to the projects demonstrate that I’m not a racist.”

Terry’s chequebook non-racism might seem like the desperate cynicism of someone cornered in a very public way, but in fact it is not at all unique to him. Quite the opposite. If anything, Terry’s is a logic that’s so familiar to us in Britain that we can no longer see just how sordid it is. Our governments, our multinational corporations, and even our society collectively have been making identical gestures for a long time. If we can’t rid ourselves of our deeply embedded and carefully structured racism, we can at least convince ourselves that our giving to an undifferentiated entity described in the vaguest terms as “charity” and “Africa” somehow renders our racism absurd, at least to us, and so allows us to construct a defence, however flimsy, against internal suspicions of racism. This is combined with the scrupulous application of a public and legal definition of racism and racist practice that is exclusively concerned with delimiting and criminalising a narrow racist lexicon. This means that only a complete idiot would choose to deploy this vocabulary and thus make themselves vulnerable to accusations of racism. With some ingenuity, we Brits have managed to concoct for ourselves a notion of racism that allows us to feel more virtuous and less racist than ever.

And yes, the Marcel Desailly to whom Terry refers would be the same Marcel Desailly who in 2004 was described on-mic by British TV commentator and former Manchester United manager “Big Ron” Atkinson as “a fucking lazy thick nigger”. Atkinson subsequently defended himself by pointing to his good relationships with other black players in the game. At the time, Atkinson told Michael Eboda, editor of the New Nation: “I’m an idiot, but I’m not a racist.”

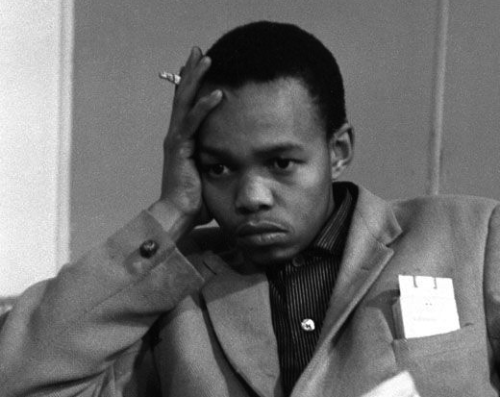

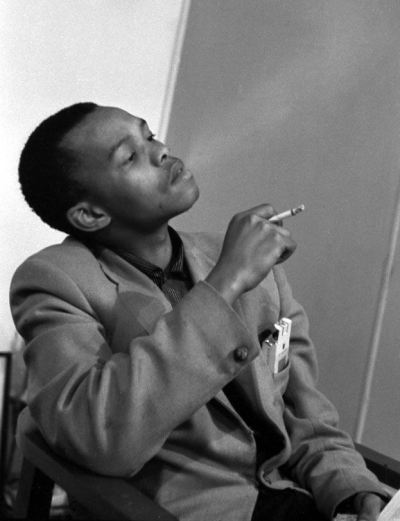

The Legacy of Nat Nakasa

Guest Post by Ryan Brown

On a warm July morning in 1965, South African writer Nat Nakasa stood facing the window of a friend’s seventh floor apartment in Central Park West. In the distance he could likely just make out the outline of the Empire State Building, a sharp reminder of just how far he was from home. Less than a year earlier, Nakasa had taken an “exit permit” from the apartheid government — a one-way ticket out of the country of his birth — and come to Harvard University on a journalism fellowship. Now he was caught in a precarious limbo, unable to return to South Africa but lacking citizenship in the United States, a place that he was beginning to feel offered little respite from the brutal racism of his own country. He was, he had written, a “native of nowhere…a stateless man [and] a permanent wanderer,” and he was running out of hope. Standing in that New York City apartment building, he faced the alien city. Then he jumped. He was 28 years old.

44 years later, nearly to the day, South African president Jacob Zuma stood before a room of dignitaries at Durban’s Elangeni Hotel to deliver the keynote address for the annual Nat Nakasa Award for Media Integrity. Given annually since 1998 by the South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF), the prize honors a journalist whose work shows a commitment to telling important and dangerous stories, no matter the political trends of the day. Facing the crowd of writers, editors and political dignitaries in the audience that night, Zuma lauded the country’s journalists as a ‘vital partner’ in protecting and strengthening South Africa’s young democracy. And staring into the past, he conjured up the name of the man who had inspired the award he was presenting. ‘This evening,’ he told the audience, ‘you are celebrating the struggle of Nat Nakasa, and many other courageous journalists like him, against a political system that sought to silence them.’

But as observers of South African politics will no doubt be aware, President Zuma’s relationship with his country’s media is nowhere near as rosy as that description suggests. Indeed, in the two years following that speech, Zuma has come to be seen to many of his critics as the very embodiment of a political system intent on silencing free speech. From the Protection of State Information Bill (dubbed the “Secrecy Bill” for its harsh repercussions against those who leak state secrets) currently winding its way through South Africa’s legislature, to the recent firestorm the ANC created over a satirical painting of the president with his genitals hanging out, Zuma has put himself and his party on the front lines of a societal debate about what can and should be done with the country’s unruly chorus of political dissenters.

In the year that I have been living in South Africa, where I am working on a biography of Nat Nakasa, I have watched the ANC’s clashes with the media with great interest. Like with so many public conversations in South Africa, debates over media freedom here frequently return to the original sin of the country’s modern history: apartheid. And in a small but fascinating way, the legacy of Nat Nakasa has become a touchstone in that conversation.

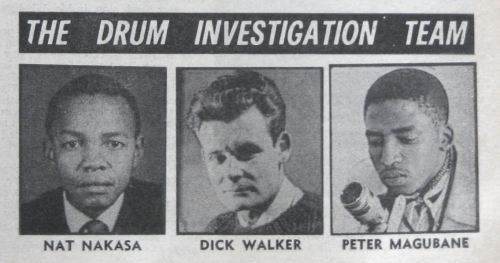

Nat Nakasa, Drum Office 1958

In 2010, for instance, Minister of Justice Jeff Radebe told the members of SANEF that the government’s proposed new press regulations would protect the country’s citizens — journalists included — from the dangers of misinformation, helping to create a media landscape that was a ‘fitting tribute to departed gallant fighters such as Nat Nakasa’. But Radebe’s Nat Nakasa also had to contend with the Nat Nakasa conjured up by critics of the government’s policy. As Oxford professor Peter McDonald, a scholar of South African censorship, put it, ‘the ghost of Nat Nakasa’ would haunt Parliament as it debated the new laws, ‘because, as [he] insisted, the freedom of expression … is an inalienable part of human dignity and a cornerstone of democracy.’ Filtered through time and memory, Nat Nakasa — the witty black writer, the exiled intellectual, the young suicide — has transformed into something far more vapid than he ever was in life: a nearly content-less symbol of the scars apartheid left on South African journalism. And so shallow a symbol, it seems, can be appropriated by whoever wants it.

Of course, there are worse legacies a person could have than to be vaguely remembered as a “gallant fighter,” a tragic hero of the anti-apartheid cause. But the fact that Nat Nakasa is celebrated this way speaks to a wider and by all accounts dangerous trend. Stripped of any substance or moral complexity, individuals like Nat Nakasa have become part of a wildly caricatured popular imagining of South Africa’s past, one that speaks in stark moral dichotomies — good and evil, right and wrong, black and white.

This view of South African history as a kind of moral fable, of course, contains a kernel of truth. After all, here is a country that was all but unhinged by its own obsession with difference, a place that for decades resisted the undertow pulling the rest of the continent toward African majority rule. I will not be the first or the last foreigner to say that the spooky singularity of modern South African history has long fascinated me. A stubborn pariah state with a white-knuckled grip on its own version of reality, South Africa was for decades a boogeyman of global politics — and with good reason.

But South Africa’s history, as with any history, is a thorny and complicated place, full of ambiguity and texture. And resistance to apartheid, in its many varied forms, was acted out not by symbols but by people, who moved through their lives without the moral clarity that historical hindsight affords. Such individuals are not simply shorthand for the injustices of apartheid. They are humans with sprawled and intricate lives that resist easy categorization.

Nat Nakasa, for instance, was no crusader for media freedom. He was simply an ambitious journalist who had the cold fortune of being born black in twentieth century South Africa, a fact that meant that throughout his life he would be constantly in battle with state-sponsored segregation. But while the Nelson Mandelas and O.R. Tambos of the world were staging protests and fermenting revolution, Nat was writing for Africa’s most widely circulated news magazine, Drum, and The New York Times. He was founding one of South Africa’s first black-edited literary magazines and penning the first black-written column for a popular white Johannesburg newspaper. In his world, freedom wasn’t the end point of a long struggle arching towards justice. It was something you seized each day — one white girlfriend, one multiracial party, one critical news article at a time.

And he did not leave South Africa as a political exile, a foot soldier of the freedom movement. He went instead, in 1964, to complete a Nieman fellowship in journalism at Harvard — in short, to advance his own career. That meant he didn’t step into the ready-made community of the freedom movement abroad. Instead, he found himself perhaps the only black South African at a staggeringly elite — and elitist — American university, persistently called upon to provide the African perspective on apartheid for audiences across Cambridge. He grew to see these gatherings with students and civic groups as wildly hypocritical. It seemed easier, he grumbled, to invite a black African to speak about his country’s fight against white rule than to address tenement housing or segregated schools in your own city.

As Nakasa’s year at Harvard progressed, he began to feel progressively more isolated and slunk toward a deep depression. His one-year student visa in the U.S. was also racing towards its expiration date. When it ran out, he would have to find another country to take him in. And despite his lack of overt politicking, Nakasa had also become a person of interest to the FBI, who opened a file on the young writer in February 1965. Five months later, under the strain of surveillance, loneliness, and a precarious immigration status, Nakasa found himself in that New York City apartment window, desperate to a point of no return.

At his funeral, South African singer Miriam Makeba — also in exile in the U.S. at the time — eulogized him with a Zulu song whose title translated as “The Faults of These Noble Men.” But indeed, what she and the others in attendance at his funeral in New York mourned was not the death of a noble man, but of one who had been, in many ways, quite ordinary. Like them, he had swept through apartheid South Africa as a young man, taking as much as he could from a state that gave little, conquering reporting assignments, women and the literary scene because he was a smart, ambitious man who saw what he wanted, and no reason why he should not have it. And like them, he had left his country not so much to take a principled stand but because it was the best option for his life and career, or so it had once seemed.

In a similar vein, the ANC’s days as a moral compass for South Africa — if indeed it ever was one — are long past. It is the ruling party in a teenaged democracy, a collection of scrappy politicians whose ambitions are far less noble than practical. They marshal figures and events in South African history in large part to prove their own legitimacy. When Jacob Zuma calls Nat Nakasa “an outstanding patriot” and a “courageous journalist,” he is drawing a line of connection between them, casting himself as a supporter of the brand of anti-establishment writing that Nat spent his career perfecting. But if that is the case, it might do Zuma and his ilk some good to take a hard, close look at the particulars of Nakasa’s life. Indeed, as he once told a student reporter at Harvard, journalists weren’t there to bend reality to fit the needs of the present. They simply “have to look at things as they are and report them.”

* Ryan Brown is a Fulbright fellow in Johannesburg, South Africa, where she is writing a book about the life of Nat Nakasa. Portions of this article originally appeared, in a modified form, in the author’s article, “A Native of Nowhere: The Life of South African Journalist Nat Nakasa, 1937-1965” in Kronos: Southern African Histories (November 2011).

July 11, 2012

Bathers at Sea Point: Photographs by Antoinette Engel

Antoinette Engel, a documentary filmmaker and photographer based in Cape Town (and a friend of this blog) took these images of bathers at Sea Point last year. We found them on the 75 photography website and asked to see the rest of the series.

Caption (from Antoinette’s 75 page): “love the way this girl was obviously begging her mom to let her swim a bit longer”

It is perhaps the ‘obviousness’ of these images, evocative of the various and numerous relationships exhibited by bodies at a swimming pool, which makes them so joyful. So here’s the rest of the series, with Antoinette’s description of how they came to be taken:

I took these photographs at the Sea Point Pavilion, a popular public salt water pool in Sea Point. One of the oldest suburbs in Cape Town, Sea Point is situated on the foothills of Signal Hill and faces the sea. Not only does it have the pavilion, it has a promenade too: a long winding walkway with an equally long grassy patch next to it that stretches along the coast for the best walk your money can’t buy because it’s free. I’d say it’s the best used public space in the city.

I took the photographs in response to a competition I’d seen on a national news site here, sponsored by a big name camera brand offering camera equipment as the prize – needless to say I decided to enter as I only have an analogue camera.

The brief was to capture a family on a typical South African holiday, and so I thought to go to the pools.

As a child my mom would make sure to pack us all into the station wagon to go to the pools. At least one adult would be along to keep watch and play life-guard, man the picnic blanket. The rest were cousins and friends, and when I was 12 an almost-crush who, lucky for me, happened to be a neighbour that was invited along. If it wasn’t the pools it was the beach or the water park in Table View where the slippery slide still stands (although I hope by now they’ve replaced it counting how many years have passed). It didn’t cost a lot, it meant getting to be in the water all day and for me and my water-baby brother who’d throw himself in the pool without abandon it meant the world.

I don’t think it cost R4 back then and it’s still really cheap by today’s standards at R11 for an adult pass into the pools.

Up until today there hasn’t been a summer I can say I didn’t make at least one trip to the pavilion… maybe I don’t cut as lean a figure in my bather anymore but I still get lots of sunshine, salt water and the buzz off the pools and the people. It gets busy, make no mistake, but some afternoons are more relaxed than others.

The day I took these photos is the first time I’ve ever been with my camera and I still managed a swim after. These were taken in Dec 2010 or Jan 2011, I forget which. I didn’t win anything, wasn’t shortlisted but I’m still really glad for that brief and the photos that came of it because I’ll always have them as a prompt to some of the best memories I cherish of my own family.

I’d say I negotiate for a living. I negotiate how to frame unguarded moments when I have a camera in my hand and otherwise access into people’s lives when the phone’s to my ear and I’m researching for the documentary series I work on. I take photographs because a part of me wants a part of life that is unmediated, which I didn’t do anything to earn but be ready.

* Antoinette Engel is currently researching for the documentary series I am Woman, and has directed two upcoming episodes, on Sandra Afrika and Marlene Le Roux, for the weekly show. Her documentary on meat production in South Africa will be broadcast on television in September.

July 9, 2012

The Reincarnation of Rockland Palace

We at AIAC are rarely known for gushing reviews. So when we heard about “The Reincarnation of Rockland Palace” as “a night of dance, style and a re-occupation of queer history, at the grounds of an old event hall in Harlem” and a documentary film project being made in collaboration with a Swedish born visual artist, our first question was… did their Kickerstarter campaign fail because the project is crap, or did it fail because of stronger social resistance to the Black and Latino youth-led LGBTQ “Kiki” ballroom scene?

I’m grateful that Palace organizers Sara Jordenö, Twiggy Pucci Garçon and some Kiki scene members took time to talk to me about their project, because we were absolutely missing the forest for the (Kickstarter) trees. Brooklyn’s 3rd Ward just donated one of their photo studios for a photo shoot with members of the Kiki scene. The Huffington Post and The New Yorker have also given them very positive shout outs since the end of the Kickstarter campaign.

What is making this reincarnation project so compelling? To start with, there is the direction of the insider/outsider collaboration. Twiggy Pucci Garçon is a powerhouse NYC-based house/ballroom runway performer, community health specialist and organizer at Faces NY, Inc. and the founder of the Kiki scene’s largest international house, the Opulent Haus of PUCCI. He says he pitched the collaboration to visual artist Sara Jordenö because she understood the importance of the Kiki scene — for the artistic development of its members and as a “pro-social movement” that supports younger members’ efforts to access health care, define community values, and develop strong leaders. (Antonio Rivera, Jai Evans, and Chi Chi Mizrahi at Faces NY, Inc. have been crucial for the development of this relationship.)

This collaboration has been directed internally, and moved forward through consensus. Twiggy and Sara emphasize that they’ve been careful to anchor and seek feedback at the Kiki Parents Council. And that’s important because Rockland Palace is not being rebuilt as a safe haven for members (though these spaces are emphatically maintained and available*). It is a call to publicly recognize the strength of the Kiki community and actively transform shared space into something that is more secure and joyous.

Hanging around their photo shoot last week, I was struck by the way Kiki scene members were working with and through the perspective of fashion photographer Marcus Ohlsson and cinematographer Lucas Millard to document each other’s performances, critique, and encourage each other to be visible as they want to be. Someone would be called up, do their thing for the camera, see how it looked on-screen, then maybe do it again. These were studies.

When I finally did ask why their first fundraiser videos didn’t go viral, organizers and performers each had their own answers. Organizers proudly claim their grassroots work. They’re not some established cultural organization, and it takes time to become visible. 5,000+ views on Youtube isn’t too shabby.

But Kiki choreographer Mathew Pasterisa put it this way — “you can’t get the energy just watching it on youtube.” Frankly, that makes us very excited to get to the ball on July 15th, and then see what Twiggy and Sara can do with the documentary. For now, we’re going to the revamped indiegogo site to support their work. Here.

* The Hetrick-Martin Institute, Heat Program and The Door are a few of the organizations that support the scene.

Tell NPR There Are Women in Botswana

Dr Refeletswe Lebelonyane

National Public Radio featured a piece this morning entitled “Botswana’s ‘Stunning Achievement’ Against AIDS.” The article reported Botswana’s very high rate of HIV and, equally, its remarkably thorough and effective response to the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Here’s an example of the success of the government’s response: “Transmission of HIV from infected mothers to their fetuses and newborn babies has been brought down to just 4 percent.”

Kudos to Botswana on this. To NPR, not so much. That sentence is the last time the women of Botswana get any mention. From there, it’s all men. This in a country in which the Director of HIV and AIDS Prevention, Dr Refeletswe Lebelonyane, is a woman. How ironic.

The centrality of women and girls to any hope of addressing anything about HIV and AIDS in Botswana, as elsewhere, is no secret. It’s not even news, at some level, except, as in this case, when it’s scanted. So, here’s a primer.

According to the Government of the Republic of Botswana, “[in] the adult female age groups, the least affected are the females aged above 50 years with prevalence rate of 12.9%. The females in the reproductive ages have been severely affected by HIV with prevalence of 29.4%. Women in the age group 25 – 29 (41.0%) are next to age group 30 – 34 (43.7%) followed by those in the age group 35 – 39 (37.8%).” This is not a case in which the government has shied away from the places and placements of women and girls in the landscape of HIV and AIDS.

And it’s not like this is new information. Four years ago, Grace Sedio, then the Project Officer of Bomme Isago Association/International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS in Botswana, wrote, “When You Think of Botswana and HIV/AIDS, Think of the Women.” Her piece, interestingly, was also a corrective to an NPR piece. Sedio’s policy advice was succinct and common sense: Support women’s sexual and reproductive health services. Support women’s human rights. Support prevention. All of that begins and ends with thinking of the women.

Sedio’s advice came out of her own experiences, out of decades of research scholarship in the field, and out of the histories of various social movements and non-governmental movements. It’s not secret or arcane knowledge. In Botswana, this is common knowledge.

Women know this and have led the struggle. In 1986, women organized Emang Basadi to advocate for and to assist women. In 1995, Dr. Sheila Dinotshe Tlou founded the Society for Women and AIDS in Africa, Botswana, or SWAABO. She was also Minister of Health from 2004 to 2008, key years in the ‘stunning achievement’ of Botswana. In 1999, K. Letsididi founded Lentswe La Basadi ba Botswana, Voices of Botswana Women, or LLBB. LLBB is a women’s writing group that links domestic abuse and sexual violence to the spread of HIV and AIDS. In Botswana, women advocates, women researchers, women writers, women organizers, women have led anything that might be called “stunning.”

Women in Botswana continue the struggle. HIV+ women continue to battle depression, they continue to struggle for decent and dignified reproductive and sexual health services and policies, they continue to struggle with sexual violence and with the gender inequalities of which it is a part, they continue to struggle with the complex of ethical and human rights that emerge in pre-natal HIV/AIDS testing. They continue to struggle with the centrality of women. Ethical and human rights are women’s rights, women’s rights are ethical and human rights. NPR does the “stunning” women of Botswana a disservice when it excludes and marginalizes them.

In “A Litany for Survival”, Audre Lorde wrote of the fear that kills all, from without and from within, and concluded: “So it is better to speak / remembering / we were never meant to survive.” The women of Botswana have been speaking … loud and proud, and they have been surviving, stunningly.

Tell NPR.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers