Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 529

June 25, 2012

In Sudan, women set the spark

The women of Sudan have had enough. On the evening of June 16, 2012, women dormitory residents at the University of Khartoum said, Enough is Enough. Girifna. We are disgusted; we have had enough.

In response to an announcement of astronomically increased meal and transportation prices, the women students staged a protest. A few male students joined in, and together they moved off-campus. Then the police attacked the students, raided the dorms, and, reportedly, beat and harassed women dorm residents. News spread, and the campus exploded. And the police again invaded. And then…something happened. Something that feels different. Some say these are anti-austerity protests or food protests or anti-regime protests. But those have happened before. Others however call them Sudan Revolts or Sudan Spring. Some dare call them the Sudanese Revolution.

Whatever they are, just remember, they began with 200 young women getting up, walking out, and chanting, Enough is enough. Ya basta!

And now, ten days later, Sudan’s President Omar Hassan al-Bashir is described as ‘defiant.’ That’s quite a statement, when the head of State, with all his armed forces and ‘informal’ security forces is mighty enough to stand up, defiant, against women and girls who, as happened in Bahri last Thursday, have gone to the intersections of town, opened up folding chairs, sat down, and chanted for lower prices, more dignity, and a better government. Defiant, indeed.

What started as a protest by a small group of women escalated, by the following Friday, into a sandstorm, which has continued to today. That includes protests, crackdowns, arrests and disappearances, State violence. And the women keep on keeping on.

As Fatma Emam notes, as she shares a photo [above] of women in Bahri blocking the road:

women do not make sandwiches

women make revolutions

women make dreams come true

Whatever you call it, this wave of protests, this revolt, this revolution, this sandstorm, women, young women, set the spark.

Digest: Malawian President Joyce Banda talks to AlJazeera

WATCH: @AJEnglish puts the rest to shame as usual with in-depth interview with President Joyce Banda… http://fb.me/1bFgFi0wi

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:24:38

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda on resolution of April political hiatus: “International pressure important but what was critical was Malawians themselves”

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:39:05

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda: Malawi Army Chief “turned the country’s history around” by backing constitution & her presidency

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:40:09

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda: Break-up of diplomatic relations with Britain under Bingu was “devastating” for Malawi

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:43:45

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda: My “number one priority” was to restore relations with IMF.

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:45:06

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda: IMF’s $150m will be used to help cushion pain felt by poor due to Kwacha devaluation

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:46:41

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda: “I respect Pres Bashir totally, & he was v close to Bingu.” Pressure from international community decisive in canceling AU meet

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:52:22

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda ducked @AJEnglish’s repeated questioning on Bashir and if she’d have had him arrested

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:53:14

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda: Chinese are not colonisers in Malawi: “Nobody has tried to influence me”

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:54:05

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda: “The good news is that African men have showed they’re willing to allow women to lead”

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:55:08

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda: “Being in politics is a love affair. You must fall in love with the people, and then hope that they fall in love with you.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:56:38

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda: “My abusive marriage was a blessing in disguise. It prepared me for leadership.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 12:58:44

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Joyce Banda: “When I ask Malawians for their votes in 2014, I want them to be able to look inside their houses & find they have an income”

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:02:13

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

Some impressions from @AJEnglish Joyce Banda interview. Tweet back with your thoughts as we go.

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:04:38

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

1. Important not to understate precarity of situation immediately post-Bingu. JB’s conciliatory style was perfect for that moment

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:06:45

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

2. JB said little to comfort those who fear she is far too responsive to external pressure (IMF, WBank, big donors)

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:08:31

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

3. With this comes the risk (highlighted by @tmkandawire) that JB may pursue “pro-poor” agenda at expense of long-term concerns

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:10:12

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

4. Bingu loved a spot of anti-imperial tub-thumping. JB has no time for this but might benefit from taking a more cynical view of UK etc

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:12:47

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

5. Why no questions about JB’s evangelicalism? Mw’s presidents so far: Church of Scotland elder, Muslim, RCatholic, now TB Joshua’s SCOAN!

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:17:50

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

6. Hopefully JB can allow other politicians to enjoy prominence in their own right. Political pluralism might be best legacy she cd leave

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:23:05

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

7. It would probably be good if JB won narrowly in 2014. Landslide govts tend to go a bit nuts in Mw (ie the second Bingu)

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:24:25

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

8. Bingu went on 2 week jaunts to Macau & kept suitcases of US$ under his bed. JB’s outfits are world-beating but so far no such oddity

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:29:13

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

9. JB relations with China will be fascinating. I think she prefers to work with moralistic devpt partners (EU etc), total switch from Bingu

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:30:44

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

10. Mw has rich tradition of presidential style, performance, to which JB is already a top addition.

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:33:47

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

11. JB has the makings of one of those “world elder” type folks (Tutu et al). Just wait til she hits the UN, she’ll charm their socks off

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Pinterest

Share on Google

Share on Linkedin

Share by email

Africa is a Country

Sun, Jun 24 2012 13:39:52

ReplyRetweet

0

likes

·

0

comments

African Asylum Seekers in Israel

Shelter, Tel Aviv, January 2008

Guest Post by Ashley Cunningham

If you follow current headlines, you may have noticed a seemingly new conflict arising in the Middle East. Recent migratory trends in Israel have led to new challenges beyond the decades long occupation of the Palestinian Territories. The tension surrounding the influx of African asylum seekers and refugees to Israel has reached a boiling point resulting in racist violence against these groups over the last several months.

In late April and early May, a series of Molotov cocktail attacks targeting asylum seeker and refugee communities, including a primary school for refugee children, marked a definite shift from xenophobic rhetoric to indiscriminate street violence. In late May, a 1000 person mob of right-wing Jewish Israelis vandalized African-owned shops and attacked asylum-seekers in the streets of south Tel Aviv. In the most recent attack, the home of Eritrean asylum seekers was fire bombed in Jerusalem, as violence spread beyond cities with high concentrations of migrants. A warning scrawled outside the house made the message clear — Africans should leave the neighborhood or suffer the consequences.

The recent attacks have instilled an increased sense of foreboding in refugee communities. Volunteers from refugee ally organizations accompany children to school to discourage attacks, similar to the situation experienced by many Palestinians in settlement plagued areas of the West Bank. Asylum seekers fear leaving their homes and many have lost what low-paying jobs they had due to governmental policies targeting refugees and their employers. Refugee aid organizations have been subject to threats of violence and even arrest for aiding “illegal migrants”. Yet this fear is not new, nor is the violence experienced by these communities.

Africans who have sought asylum in Israel since the end of 2006, currently number between 21,000 and 60,000 people, with the majority coming from Eritrea and Sudan, traveling through the Sinai Peninsula. Though Israel is a signatory of the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees, and both the 1954 and 1967 Protocols, the Israeli government does not have a functioning asylum process and has not adopted associated asylum legislation. As such, the situation faced by refugees in Israel is tense, as the asylum process is arduous; work permits and social services are lacking and/or outright denied. To date, the Israeli government has recognized less than 200 asylum seekers as refugees, portraying most as economic migrants traveling to Israel for work. UNHRC recently reported that in 2011, only one of 4,603 asylum applications was approved, with an additional 6,000 cases pending review.

As the number of Africans in Israel increased, so have levels of hostility from local Israeli communities, particularly in south Tel Aviv. The recent attacks that received heightened media attention are merely a continuation, though more explosive, of anti-African sentiments that have pervaded the Israeli state since the arrival of Ethiopian Jews in the 1980s and early 1990s. Anti-African protests in Tel Aviv began in 2010 and the home of Sudanese refugees in the city of Ashdod was firebombed in early 2011. The media, both in Israel and abroad, has largely failed to report the presence of racial incitement and violence as a process constructed over time, preferring to portray recent events as an overnight phenomenon in reaction to uncontrollable migration flows.

The American media landscape has largely ignored the struggles of African asylum seekers in Israel, focusing more closely on high-level political events surrounding the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and tensions with Iran. In the period preceding the recent violence, there was only sporadic reporting of refugee-related issues, even as Israel began constructing the world’s largest asylum detention facility in 2011. This facility in the southern Negev is expected to open in late 2012 and will incarcerate upwards of 10,000 people, including children.

Of the limited reporting that has been done, most lacks a serious analysis of the political situation in Israel and displays a number of disturbing trends, namely the mimicry of government security claims, the prioritization of Israeli voices over those of refugees themselves, and a failure to address the role of political figures in driving racial incitement. A general lack of context and clarity has resulted in a number of misleading headlines and news reports. Following the recent xenophobic riots in Tel Aviv, CNN published a report titled “Hundreds protest in Israel illegal immigration battle,” in which the outlet refers to asylum seekers as “illegal African migrants.” Even more damaging, when highlighting the violence and arrests that ensued, the outlet does not illuminate who were the perpetrators of such violence, leaving it unclear to the reader that it was Africans asylum seekers that were under attack.

The New York Times displays similar trends, though paints a picture of re-establishing order in response to the chaos resulting from migration. Articles published by Isabel Kershner and Ethan Bronner include headlines such as, “Israeli Leader Pledges Hard Line on Migrants” and “Israel Acts to Curb Illegal Migration from Africa.” Bronner takes it a step further in parroting racist and discriminatory language such as the usage of the word “infiltrators” to describe Africans in Israel.

Israeli media demonstrates similar trends, though there has been a marked shift in the general media landscape. Since the onset of the recent attacks, a number of news outlets began interviewing asylum seekers in response to the violence. The inclusion of these individuals has been a rare occurrence over the years, as even more progressive news outlets such as Haaretz have largely given greater space to Israeli elected officials and their associated ‘law and order’ narratives.

The recent inclusion of asylum seekers is not itself without flaw. Though these interviews illuminate the experiences of asylum seekers in Israel and touch on their want of greater rights including recognition as refugees, the overall portrayal erases the agency of these individuals, rendering them solely as victims of violence and exploitation. Very few outlets have reported on protests petitioning for refugee rights or asylum seeker-led demonstrations outside the Eritrean embassy demanding political reform. As a result, it is difficult, if not impossible, to pinpoint a political solution that is sought by the individuals most seriously affected by recent events — African asylum seekers themselves.

* Picture credits: Activestills.

June 23, 2012

Her Zimbabwe

A new Zimbabwean is starting to gain both readership and wider media attention. I put some questions to Fungai Machirori, the founder and managing editor of Her Zimbabwe.

Where did the idea for Her Zimbabwe come from?

In 2011, as my Masters thesis, I conducted a study which investigated how more meaningful exchange and collaboration could be encouraged between Zimbabwean women in Zimbabwe and Zimbabwean women in the diaspora. With the increasing feminisation of Zimbabwe’s migration, I felt a need to research whether and how women were developing diasporic networks and coalitions; and whether and how these were supported by Zimbabwe-based networks.

My study revealed that Zimbabwean women’s movement-building has largely disintegrated due to increasing state politicisation and NGO professionalisation (or ‘NGO-isation’) of women’s organising. Additionally, the women’s movement in Zimbabwe has created high barriers to entry (with criteria such as experience and history, or rather lack thereof, within the movement being some of these barriers) for young women.

Furthermore, the diaspora has been largely (mis)understood as a politically motivated (that is, anti-ZANU PF) and homogeneous group of people whose main function, at least in Zimbabwean discourse, has been to buoy our economy through the turbulence of the nation’s socio-economic crisis by remitting finances. Few platforms have paid attention to the challenges that Zimbabweans within the diaspora face in negotiating and articulating a transnational identity. And such an identity is complex; for instance, Zimbabwean women in the diaspora have expressed that they enjoy greater freedom to question gender roles and identities, yet concurrently experience nostalgia for home.

Women within Zimbabwe, however, have had limited freedom and environmental support to challenge patriarchal norms and redefine gender roles (the women’s movement has provided such spaces and yet it has been faced with certain structural challenges, as mentioned previously). I started to observe how many young women in Zimbabwe were using new media, particularly blogs, to speak their various truths. And as the number of active female bloggers has increased, so too has the level of discourse around the dynamism and contradictions of life as a Zimbabwean woman. The potential for new media to encourage Zimbabwean women to freely interrogate and express their multiple identities and worldviews became obvious to me.

All these discoveries were happening at the same time as I was a runner-up in the World Youth Summit Awards held in Austria. There, I really started to see how young people were honing the potential of new media to make a difference in the world. And that’s really when I thought seriously about how a feminist cyber-activism platform could look in Zimbabwe.

So all those experiences informed what was birthed as Her Zimbabwe on March 13 this year.

How would you sum up the identity of the site?

It’s a space where we encourage women to speak up on issues, either as generators of content, or as participants in discussions. It is a space also, where we celebrate being women and having multiple identities and roles and influences. It is what I like to call the ‘alternative’ space; a space where we tell the alternative stories, the untold narratives.

It is also a space where we celebrate men who empower women; we understand not only the social relations between men and women (which has been the general portrayal of gender issues in Zimbabwe), but also the relations among women and the heterogeneity thereof.

Who is your target audience and why?

While Her Zimbabwe reaches a broad spectrum of women, its core audience is Zimbabwean women (locally and diaspora-based) aged 20-35; and women with access to the Internet, an ever-growing demographic. This does not, however, limit Her Zimbabwe to focusing solely on issues affecting this age group as the experiences of both younger and older Zimbabwean women are crucial to achieving more holistic representation and discussion.

We have targeted this age group as I, as well as the team members I work with, are more conversant in issues that affect this demographic than any other. Also, as I have already mentioned, there have been barriers to entry into mainstream gender discourse for women falling into this demographic. We are focusing on women with Internet access because we want the women who contribute to Her Zimbabwe to have right of response; in other words, we want the women to be technologically empowered to respond to issues and matters and arising from their stories. Where a story has been sought from a woman without the digital components to be able to access the site, the story is no longer authentically hers, but rather something that we have extracted from her for other people to view.

Are you read more by Zimbabweans in the diaspora, or those still at home?

I don’t have the most recent Google Analytics statistics, but we had been inching towards a million page views. Of those who visit the site, the highest number is in Britain, followed by the United States. Zimbabwe ranks third, with South Africa fourth. Of our Facebook page followers, we have an almost equal spilt; as at 21 June, we had 1 506 Facebook followers. 756 are in Zimbabwe and 750 are outside Zimbabwe with almost a third of those outside being in the UK, and another third being constituted of those in South Africa and the United States. Australia then follows with various other countries having much smaller followings. This correlates strongly with statistics around of Zimbabwe’s diasporic communities, with the bulk being situated in the UK, the US and South Africa. Twitter has been much slower with about 500 followers to date.

What is it that you offer that is new and different?

I think, first and foremost, we are not excluding men! I feel this is very important. Our website was designed by a man who understood what the ‘Her Zimbabwe’ ethos is all about. Our logo was also designed by a man. And these services were offered free of charge simply because these men bought into the Her Zimbabwe idea. So the site wouldn’t exist – as it does – without them and I am always mindful of that. Women need men as is true vice versa. We cannot overcome patriarchy without each other as it is a system that oppresses both sexes. Thus, Her Zimbabwe has a ‘His Zimbabwe’ section where we invite men to talk through issues.

Of our Facebook followers, 27% are male and they are not shy to comment about menstruation and other issues that men usually dissociate themselves from. And perhaps most importantly, women are talking about themselves to each other and to men. This is essential as the sexes need to finally start talking to each other in the same forums.

We’ve also just been running a series entitled ‘Lessons From My Father’ where we’ve seen women share profound stories about the influences of their fathers. And whether good or bad, the whole point with this series was to acknowledge the role that men play in women’s lives.

We also offer dynamic and witty content that challenges people to think and develop broader worldviews. We show the world out there that political quibbling is not all that is going on in Zimbabwe. Women are thinking, innovating, excelling, living. This is also an important outlook for Zimbabweans in the diaspora who are generally fed the usual doom and gloom fare by most media houses. We create a space for women share stories. Zimbabwe, as a nation, suffers from poor documentation of women’s moments in history. And I want Her Zimbabwe to contribute a piece to the collective memory of this moment.

You’ve had posts on interracial relationships, on celibacy, on ethnicity, on fathers… are you getting a sense of what kind of material is most popular?

Just looking at site analytics, one of the biggest stories to date is about a young woman’s experience of being coloured (of mixed race heritage) in Zimbabwe, of neither being black enough nor white enough to be socially accepted. That is a highly neglected story in Zimbabwe and it was really important to be told, not just for other coloured women, but also those who have failed to understand these women’s diverse experiences and histories. Another article that really got people talking was about a young woman reclaiming her vagina from patriarchal and societal expectations. Generally, articles that have looked at identity issues that society has generally suppressed have been very successful.

From our Facebook discussions, it’s interesting to gauge the dynamism of thoughts and beliefs. I have tended to notice how those people who are not based in-country have a different outlook or perception on a topic to those who are in Zimbabwe. And people start engaging more dynamically by having these interactions. Everyone is enriched and better informed.

There is generally an inclination to matters that discuss cultural and social expectations placed on women.

What are your ideas for developing the site — in terms of content, direction, audience… and financial sustainability?

We are currently working on a structure for Her Zimbabwe, wherein I am hoping that we can get funding to constitute a secretariat. This will greatly increase the number of hands on deck thus alleviating the work pressure I have. I have fantastic friends who have volunteered their services towards Her Zimbabwe. But as they work in full-time employment, their contributions are curtailed by this. We are collectively looking for funding opportunities and trying to think of sustainable solutions.

I am also gauging what content appears to be more robust and captivating and trying to develop programmatic focus towards that. I see Her Zimbabwe becoming a hub for cyber discussions on various issues affecting Zimbabwean women, in various formats not just limited to storytelling. We’d also love to increase our video, audio and pictorial storytelling in the process.

In terms of audience, once we have our secretariat going, we can formalise this process by having significant presence at and within various forums. But for now, the great response we’ve received has proven to us that Her Zimbabwe is selling itself well. It can only grow bigger.

But before it does, we have to evaluate this amazing pilot phase that has just come to end mid-June and target our actions according to the findings we’ve made.

Gaddafi Archives at the London Photography Festival

Queen Elizabeth II with King Idris, the Duke of Edinburgh in Tobruk May 1954 with British military official (Courtesy of Peter Bouckaert/Human Rights Watch)

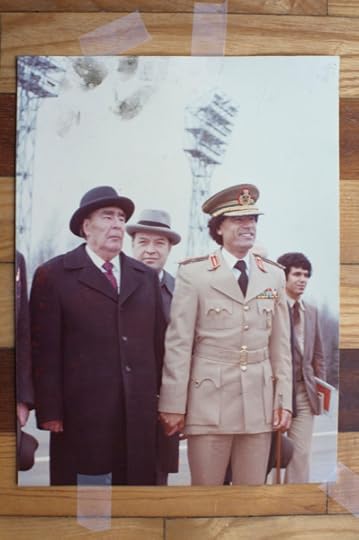

The ‘Gaddafi Archives – Libya Before the Arab Spring’, which opened this week at the London Festival of Photography is an embarrassment of riches. This exhibition of images recovered from the remains of Gaddafi’s archives and rephotographed by a team assembled by Human Rights Watch, opened at UCL. The first three rooms document official life in Libya from reign of King Idris and then, after the military coup in 1969, extensive images of the five decades of Gaddafi’s rule, including encounters with other leaders, from Nasser to Yasser Arafat, which give some suggestion of the complexion of Libya’s recent diplomatic history.

Colonel Gaddafi and Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Soviet Union, holding hands in Moscow, April 27th, 1981 (Courtesy of Michael Christopher Brown/HRW)

In the next room, television footage of the show trial of Sadiq Hamed Shwehdi in a Libyan basketball stadium in 1984. Shwehdi’s testament ‘admitted’ to being a member of the ‘stray dogs’ and collaborating with the Muslim Brotherhood’s attempt to bring down Gaddafi’s government, until the audience – many of whom are children – scream for his execution, which takes place shortly afterwards on live television, an event remembered by many Libyans. In the same room are copies of letters from the CIA to Libya’s secret services, arranging the extraordinary rendition of terrorists to their control. More materials on display include images of military pageants, weapons stockpiles, the Chadian-Libyan conflict, pro-Gaddafi artworks from Sirte and a film explaining the context for Gaddafi’s murder.

Two people who were executed at Benghazi sea port. April 7, 1977 (Courtesy of Peter Bouckaert/HRW)

At the opening of the exhibition Peter Bouckaert, Emergency Director of Human Rights Watch, explained that the images were collected at a time when Libyans were setting fire to Gaddafi’s government buildings in the belief that this would ensure he couldn’t return. It would have been interesting to see more evidence of UK collaborations with Libya before the NATO intervention but no doubt more of these invaluable archives will be available soon. The exhibition represents part of a vast project, which Bouckaert described as a contribution to ensuring a visual heritage for Libya’s future, and the photographs have been handed over to the National Transitional Council.

More information on the ‘Gaddafi Archives – Libya Before the Arab Spring’ (open until June 29th) is available here.

June 22, 2012

Friday Bonus Music Break

Quite the mixed bag this week. ‘Disco Malapaa’ by Arusha’s Jambo Squad above; nine more below.

Like Jambo Squad, Mokoomba (from Zimbabwe) switch into Latino mode halfway in their new video:

Anbuley’s ‘Oleee’ arrives just in time for European summer:

Also based in Europe, although his latest video (like the previous one) suggests a longing for elsewhere, is Gaël Faye:

Simphiwe Dana decided to take a step back from social media a while ago and concentrate on doing what she does best: speak truth through music:

Still in South Africa, taxis and drifters:

South Africa based poppy Cameroonian Denzyl:

From Guinea, the Matoto Family:

Sierra Leone’s Refugee All Stars signed up for a cause:

And — to turn it down a notch — Ablaye Cissoko and Volker Goetze wrote a subdued lament for Haiti — quite beautifully — and recorded a video for it in Gorée:

A Room Adrift in London

Here in London we have been having a lot of trouble with pageants. After the riots last August, the administration are hoping that plans for this summer – the Olympics, the Hackney festival – will be distraction from the impoverishment of life and extensive violence done by the conservative government to the state. Last month the Queen floated down the Thames on the barge – we were assured that the world was watching their television set – and, in celebration, the city was millitarised and policed to an extraordinary degree. Half-way through her stately progress the barge passed underneath a small ship, perched high on top of the brutal concretes of the Queen Elizabeth Hall, an arts venue on the city’s south bank. The ship, a collaboration of artist Fiona Banner, David Kohn Architects, built by Living Architecture, is named Roi des Belges after the boat Joseph Conrad sailed up the River Congo before writing Heart of Darkness. The project A Room for London/Roi des Belges, seems to have been conceived in this dubious tribute. We blogged about it with some incredulity when the news first hit the internet.

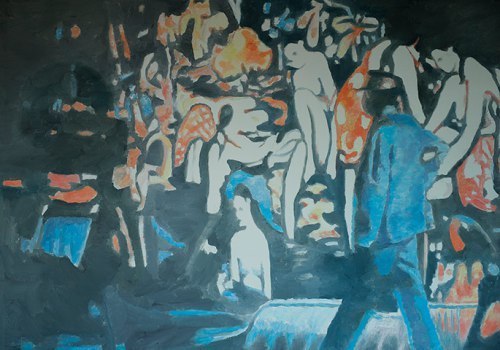

Artangel, an innovative British London-based commissioning body, invited a series of artists to inhabit the ‘ship’. The first of these was digital cartographer and Conrad-enthusiast James Bridle, whose innovation was to set up a weather station on the ‘ship’ and to create ‘a ship adrift’, a log-book for a fictional double for the ship whose movements, determined by weather conditions in London, you could follow on twitter, if you so choose. Then David Byrne spent a comfortable day in the ship, and compiled a rather appealing track from London’s noises. Then artist-curator Jeremy Deller invited a musician, Chuck, to play songs from the ship’s stern to the passing crowds below. Then Fiona Banner invited celebrated British actor Brian Cox to read Orson Welles’s unmade film of ‘Heart of Darkness’ (the reading, all 157 minutes of it, can be seen here, but only until June 30th). In April Belgian painter Luc Tuymans was invited to spend a day there and produce a painting based on a scene from Conrad’s novel. Tuymans decided instead to base his painting on a still from ‘The Moon and Sixpence’, a 1942 film adaptation of a Somerset Maugham novel inspired by the Tahitian adventures of French painter Paul Gauguin:

The particular sequence I’m interested in comes at the end of the film. Strickland, the main character, is already dead. His doctor, who speaks with a thick German accent, travels to Tahiti to visit the village where Strickland used to live. He meets with the local wife of the deceased painter and enters his cabin, which was the working place of the artist. Up to this point, the entire movie is in black and white. But when the doctor enters the space, the film jumps into bright colour.

Tuymans’s painting – Allo! – can be seen below, a man wearing a suit walking past a large and generic painting of sloping, not inelegant, women. The painting is of a photograph of a still image of the painting in the film taken by the artist from a computer screen. This confusing series of framing devices clearly attempts to deconstruct the image of the ‘exotic’ to the extent that it becomes merely an image of the artist himself, and Tuymans’s head – reflected on the computer screen – is visible as an indistinct presence on the ‘surface’ of the painting. Tuymans’s portraits of Patrice Lumumba practiced a similar form of distortion through (mis)memory.

The insistence that the framing device becomes a totalising subject of the painting – put more simply, how you look defines what you see – is a familiar one within academic discourses about travel literature. The decision not to paint an image based on a fictional text (at least partly based on actual life experience in central Africa) but a painting from a fictional film inspired by (Gauguin’s) paintings of actual life experience in Tahiti, inserts pastiche as a defense mechanism against accusations of exoticism. This seems sensible, except perhaps in light of Conrad’s own attempt to do the same. Though he had made a similar journey to the one his novel describes, Conrad decided to place the narrative in the mouth of Marlowe, who tells the story to an unknown narrator on board a commercial ship at Gravesend, the last outpost of ‘civilization’ at the mouth of the Thames. Chinua Achebe’s famous attack on the novel describes this:

It might be contended, of course, that the attitude to the African in Heart of Darkness is not Conrad’s but that of his fictional narrator, Marlow, and that far from endorsing it Conrad might indeed be holding it up to irony and criticism. Certainly Conrad appears to go to considerable pains to set up layers of insulation between himself and the moral universe of his story. He has, for example, a narrator behind a narrator. The primary narrator is Marlow, but his account is given to us through the filter of a second, shadowy person.

I don’t mean to suggest that Tuymans is making the same mistake: in his painting the artist’s own shadowy presence is no more or less socially determined than the blanched bodies of the women or the intermediate figure standing in the foreground. And, unlike Conrad, the painting is validating its obsession with an unknowable terrain through mediating figures. Tuymans’s painting is interested in the vague and distant exotic which is not known but created in paint.

The most recent celebrity inhabitant was the Guardian’s art critic Adrian Searle whose good-humoured account of the day was published last month. The article opens with Searle standing naked at night in front of Tuymans’s painting. Searle describes his approach to the painting on the wall of his cabin: “I sit and drink with it; dance around the cabin in front of it and get undressed with it.” ‘Apocalypse Now’, Francis Ford Coppola’s film relocation of Conrad’s novel to 1970s Vietnam, famously opens with the protagonist dreaming from his Saigon hotel room of forests destroyed by napalm, then freaking out and smashing his mirror. Again and again, these works serve as a mirror in which the distortions of the white male body are seen.

Searle remarks that the room ‘is beginning to get to me’ and starts to have fun: “I dance about the cabin, waving my arse first in the direction of the Houses of Parliament …” It’s a shame this rational behaviour need be induced by such a preposterous setting. Searle’s identification with the painting produces an excellent analysis: “Approaching his subject, Tuymans keeps a distance, like someone visiting the sick, hovering near the door in case they might catch something.” He spoke to Tuymans before entering the room, and tells us that the artist “said his painting is his joke on modernism, dealing with fake ideas of the new, the exotic and the colourful.” This mock-mock-Gauguin painting, whose subject has disappeared into the abyss of post-modern self-reference and cannibalising tradition, disputes the idea that art can know anything outside the artist himself. This is a conclusion Achebe identifies in Conrad also:

[I]f his intention is to draw a cordon sanitaire between himself and the moral and psychological malaise of his narrator, his care seems to me totally wasted because he neglects to hint however subtly or tentatively at an alternative frame of reference by which we may judge the actions and opinions of his characters.

Conrad, writing from ‘literary’ London, was unable to imagine an African subject with language or culture not imposed by imperialism but natural and universal. Achebe says that this is why he cannot consider Conrad’s novel to be art. And Tuymans’s painting? Searle concludes:

Allo! is a weird thing to spend the night with. But then, so am I. The horror! The horror!

The last emphatic sentences, quoting Conrad’s famous slogan, confirm our original suspicions: this is not a special lebensraum for London intellectuals but a theme-park profiting from the cultural histories of European colonialism. Amadou & Mariam played a little gig there and on BBC Radio 4 Mariella Frostrup had a conversation with some novelists about ‘literary’ London, but there doesn’t seem to have been anyone reflecting on the legacy of Conrad and London’s imperialist past (or indeed its imperialist present). If there’s a problem with Searle’s account, it isn’t lurid enough, and the organisers seem to have failed to invite a more skeptical approach to their project. Tuymans’s bathers belong in a painting but Gauguin was painting real prostitutes; the distance doesn’t affect the fact of the violence at the heart of the image. The truth is, of course, that you can’t see anything from the ship that isn’t visible on the streets of central London: the golden city of our daydreams is always around the next bend in the river. The main flaw of ‘Apocalypse Now’ is that it cuts out the scenes in the capital which frames Conrad’s narrative. All those films which decide that (pace Sartre) Hell is trying to occupy someone else’s country never adequately notice that imperialism starts at home. The site of conflict between the individual in London or Belgium and imperialism is not just in the museum or the gallery, and certainly not in ridiculous pastiche projects from literary history, but in the streets, at home or in the workplace.

Last December, the UK’s Congolese communities descended on central London to protest against the contested elections in the DRC. 139 people were arrested in one day. Protesters claimed that the international community had to take a role, when international corporations had been profiting from the conflict, and fueling it.

Given this recent history, which artists and writers have been documenting the network of relations which continue to exact imperialist violence? Sammi Baloji’s work, for example, measures the extraction industries in the DRC against the human body, a form of thinking which starts to expose the violence of global industries towards individuals and communities. Teju Cole’s novel Open City wrote a constellation of encounters which connected life in New York and Brussels to their colonial histories. Could the Room for London organisers have invited into their Conrad-themed installation someone capable of thinking about contemporary forms of colonial violence – or would it have been offensive? If so, perhaps the whole project is offensive. Inter-cultural conversations happen, in art and outside it, not just because of a lust for adventure or self-knowledge but as necessary acommpaniments to commerce and colonialism. The computer screen which gave Tuymans his image may well have contained coltan, the mineral whose illegal trade finances violent struggle in eastern Congo. Recently, corporations based in America and London have been accused of endangering the precarious political situation in order to exploit the country’s natural mineral resources. As Achebe reminds us, ‘poetry surely can only be on the side of man’s deliverance and not his enslavement’. The real work of art has new maps of material complicity to contend with.

* Photo credit: peripathetic.

Mubarak is a Diva

So much has been written on the Egyptian presidential elections already that it is a bit overwhelming to weigh in on them now. So let me be clear – this post is intended only to introduce some of our illustrious presidential candidates, the reasons why it never mattered who prevailed, and the awesome post-election battlefield that is Egypt. Oh, and Mubarak’s rumoured demise.

I’ve mostly been tweeting stream-of-thought (in epically inappropriate language) about the elections, but I would like to emphasize one of my comments during the first round of the elections: “if you voted for Shafiq, please never speak to me again. Agreed?” Who is Shafiq? you might be asking. Well, here is a bare-bones breakdown of a few of our mediocre presidential candidates:

Ahmed Shafiq: Military man, former PM under Mubarak. Purported loser of the second election rounds, though his camp alleges otherwise.

Mohammed Morsi: “Brother Muslimhood” AKA Freedom and Justice Party AKA Ikhwan candidate. Likely winner of the second round, but who knows anymore.

Hamdeen Sabbahi: Nasserist candidate for the Dignity Party.

Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh: Formerly Muslim Brotherhood, secretary-general of the Arab Medical Union, and still pretty into Islamist politics. The Salafi party endorsed Fotouh, but he’s actually kind of a righteous dude when you get right down to it.

Amr Moussa: Stank-faced professional politician, wearer of conservative ties and muted suits. I honestly paid no attention to him during the elections, he’s only here to round out the bunch.

There are more but you can go here to read about the other guys.

Most of you know this part of the story: the first election round came down to Shafiq and Morsi, both camps continue to battle it out despite the (still unannounced) second round of votes, Egyptians are still all over the streets in protest, the Supreme Constitutional Court invalidated Egypt’s elected parliament at the behest of SCAF, our military council, which is still running the country as an autonomous body. And they will continue doing so, for as long as they are able to hold power (which is probably going to be a long while). “Down with the next president,” indeed.

A closer look at SCAF’s continued hold on power is especially frightening, but not quite as surprising as Western media has made it out to be. According to GWU professor Nathan Brown, the ‘supplementary constitutional declaration’ issued by SCAF “really [does] constitutionalize a military coup” by more firmly establishing their long history of controlling the Egyptian government. I’d recommend reading Brown’s “hastily jotted down” observations here.

While everyone in the West seems really shocked by the turn Egypt’s first post-Mubarak elections have taken (the Carter Center, which monitored the elections, stated “grave concern about the broader political and constitutional context, which calls into question the meaning and purpose of the elections”), I’d like to summarize the attitudes of the Egyptians who have been paying attention since 1952: “Duh.”

We knew SCAF wouldn’t “hand over power,” and it’s quite telling that they control enough of our country that we even phrase it as “handing over power.” So SCAF has apparently decided that the parliament goes, and whoever ends up as the incoming president will only be a “transitional” figurehead until they can draft a new constitution. C’est la vie. “Ya3nni.” We’re used to this. No big deal.

So what I really want to talk about now is Hosni Mubarak. Hosni Mubarak, convicted of ‘allowing’ for protesters to be killed during the beginning of the uprising (a conviction which many have argued allows for an appeal), had to go and fake die right in the middle of all this mess. Diva. Attempt to distract Egyptians from SCAF and get them off the streets and into their homes. Etc.

The first round of news I heard of this forwarded that Mubarak was “clinically dead” according to “some officials,” shared by both Egyptians and non-Egyptian news sources. I then noted, with great amusement, the immediate “I’ll believe it when I see it!” response from many an Egyptian on my Twitter feed. Now, just as I believe that Twitter was not what made our revolution, I fully admit that my own paltry Twitter feed is not representative of a significant number of any population. But the instantaneous skepticism regarding Mubarak’s purported death, even as just as many people were sharing the unsubstantiated news, proves my faith in the Egyptian people is well-placed.

Mubarak is not dead. Nor is the humour and immense devotion to our revolutionary society that Egyptians who are not featured on your nightly news shows possess. I suppose we are in “turmoil” and that “tensions are high,” but when in the past year – and I’d argue, in the past 30+ years – has this not been the case? And yet, we manage to keep going. And keep fighting. And keep laughing.

All that said, it appears Egypt is still much closer to becoming a “real democracy” than CNN & co. would have you think – we all went out to vote on a choice of crappy candidates and an absurd judicial intervention rendered everything irrelevant.

June 19, 2012

The Very Best’s “Kondaine” and Village Beat’s advocacy

The musical group, The Very Best is a tandem between Malawian singer Esau Mwamwaya and London based producer Johan Hugo. Both met and live in London. AIAC has dedicated several posts to their music. From scanning a few of their videos, it seems they often poke light of the music video genre, taking playful measures with “Yoshua Alikuti,” which riffs off of Lil’ Wayne’s “A Milli” and “Warm Heart of Africa,” which makes use of the green screen to project ‘African’ scenes replete with two backup dancers familiar to homegrown music videos. The song, “Kondaine” released off of The Very Best’s new album MTMTMK, is no exception. It has The Very Best plus their guest singer, Nigerian-born Seye, travel to Northern Kenya, visit a witch doctor, drink Kondaine, and turn into goats. Pretty light hearted, except for the graphic goat scene, which, if not for the upbeat tone of the song, would fall more in line with a darker message. But wait, you may ask, why shoot your music video in Kenya?

Luckily the final seconds of the video answer that question: director’s choice. Both new singles off of MTMTMK were shot and directed in collaboration with the California activist arts based organization Village Beat. “Yoshua Alikuti” was shot in Nairobi, and “Kondaine” in Northern Kenya. Village Beat is active in both of these areas, currently filming a documentary on the plight of Kenyan street children in Nairobi, and working to raise funds for a music festival to increase awareness of the displacement of the Turkana people in Northern Kenya, and the controversy surrounding the building of the Gibe III Dam.

All well and good, but what does this music video addendum really do, besides act as a plug for Village Beat’s advocacy efforts? Let me lay it out below:

Love and respect to our Turkana friends of Epiding village in northern Kenya — particularly Matet & MC Maji Moto. Sacrifice and ceremony are traditional practices of the Turkana tribe used for events such as marriage, death and in our case, the welcoming of visitors. Drinking Kondaine — the magic potion — is not a traditional Turkana practice. Therefore, no members of The Very Best were actually turned into goats. To know more, visit www.villagebeat.org

With the exception of its guest extras’ shout-outs, all it does is call into question the music video even more. I generally don’t expect music videos to provide many hard truths, except what I learned from rap videos, that street living is rough. Now Village Beat wants to correct my “assumptions” about Turkana culture, as if I were in fact making any, and in the very last seconds have me reprocess this whole video in terms of reality, seeing it as inauthentic, instead of as a visually entertaining spoof on visiting a “witch doctor”. Now I have to think, why were the Turkana even highlighted in the first place if they have no relation to music’s subject matter? Oh right, because Village Beat wanted them to be.

But to close in Village Beat’s defense, if I were to have immediately coupled Kenyan rural life with a tradition of black magic, this addendum would provide me with a healthy dose of reality check: hey now, it’s just a music video.

June 18, 2012

Curating Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction

Currently showing at the Arnolfini, the exhibition ‘Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction’ brings together various fictions. Science fiction becomes racial fictions become state fictions that fold into colonial fictions and back again. Science fiction becomes an umbrella for a range of discourses that, with the distance of futurity, are exposed in all their strange power. A startling and witty symmetry is revealed through the chosen works of the exhibition. We blogged about the exhibition speculatively here, and I wrote a review of the show in the UK magazine, The Wire. For AIAC, I asked the two curators of the exhibition – Al Cameron and Nav Haq – to explain a bit more about their interest in these ideas, and how the exhibition came about.

What sparked your interest in science fictions of (and in) the African continent?

The starting point was noticing a specific tendency that seemed to be emerging in contemporary art, cinema, and wider culture, and thinking about how we could approach this within the context of an exhibition. In some ways, we also felt that this work was different to Afro-futurism, at least in its applied sense. In fact, though parallels can be made, we feel it is something that to some extent had emerged independently.

To us, Afro-futurism seemed to be a discourse about the (usually African American) diaspora’s participation in a technological futurism, as opposed to being tied to a sense of roots and tradition with which the European imaginary has daubed African-originated culture for its own purposes. That was a kind of machine-theory or a post-humanism – as you pointed out in your review of the exhibition in the Wire there was also an attempt to bypass the association of African origins with orality, which was manifested in multiple attempts to subtract the pure voice from late-20th century dub and techno, for example. A lot of the works in this exhibition – Omer Fast’s for example – place speech at the centre of their stories. In Neïl Beloufa’s film Kempinski (2006), the Malian characters inhabit the future through interviews in the present tense. Here, a series of voices that would normally be excluded from discourses on the future are made audible.

We believe that the works in our exhibition do something different in the broadest terms. In general, they place human desires, rather than technological futures, at the centre of their speculations. Technology appears in the works mainly as an oppressor.

The word superpower in the exhibition’s title goes against what most people would associate with Africa. Why did you choose this word?

We actually borrowed the title from Mark Aerial Waller’s installation film, Superpower – Dakar Chapter (2004), but clearly it indicates a shifted perspective. The idea of superpowers obviously references the science fictional idea that humans might have extra-terrestrial abilities, and in Beloufa’s film, where Malians are asked to imagine the future as if it was present reality, they propose things like telepathic communication and teleportation. Then again, the title performs a reversal of narratives and expectations about the global order of things. Throughout modernity and subsequent epochs, Africa has been subjected to the almost continual interference of outside states with the ability to project dominance beyond their borders, whilst finding those borders difficult and dangerous to cross in the other direction.

Through the three chambers of Omer Fast’s installation, Nostalgia (2009), the usual narratives about patterns of migration are disrupted, and a story about a West African immigrant’s experiences in the West is collapsed into a claustrophobic fantasy about Europeans seeking a better world in a retro-futuristic Africa. Kiluanji Kia Henda’s Icarus 13 (2010) imagines an Angolan mission to the sun – a ridiculously ambitious project, but one which the Luandan monuments already prompt. The tomb of António Agostinho Neto, Angola’s first president, was gifted by the USSR to Angola. Taking the form of a futurist spacecraft, ready on the launchpad for blast off, it promises an ambitious technological future for the fledgling Angolan state: the first mission to the sun, beyond the reach of our present superpowers. Yet, perhaps in its implausibility it cements the real historical dynamic of this future, one unevenly bequeathed by a superpower to its vassal state.

Of course, this fantastical scenario didn’t actually emerge – Neto’s socialist ambitions were dissolved in a quarter-century of civil war, while the USSR would over-extend its global reach and collapse its visions of collective prosperity. Both utopias burned up like Icarus who got too close to the sun. Only in Kia Henda’s speculative fiction does the improbable feat succeed. To extend this thinking, the sun itself has been mythologized throughout history as a supreme entity, or a superpower, with the power to burn up humans who come too close. Nevertheless, in Icarus 13, the attempt to make a claim on the future on behalf of an African state reverses the usual scenario wherein outside bodies, whether through global military power, politico-financial constraints like the “structural adjustment programmes”, or indeed through culture and media hegemonies, appropriate the right to describe the future.

A still from Beloufa’s film Kempinski

What, in the context of the collected artworks that form Superpower, is your understanding of science fiction?

Science fiction takes on many forms – it has offered experimental timespaces for testing alternative ideas and speculating on possible and probable trajectories, but equally, it describes, for example, a steady stream of mindless blockbusters which continue to trade on ossified expectations and lazy assumptions. We don’t profess to be experts in the genre, but in the context of this exhibition and the works shown, it seemed to offer a number of possibilities, especially in terms of how re-orientations of tense and folded notions of time might reconfigure our view of the present.

Perhaps the key activating principle it has in the context of this show is in the way it can produce complex diagrams of time. In general, although not exclusively, the genre is concerned with the intervention of possible futures into the present, like the light from distant stars on which Mark Aerial Waller’s film relies in a structural and narrative sense. Whether or not it imagines distant times or galaxies, SF is essentially always concerned with the present.

What seems particularly striking about the assembled works is their collective comment and critique on contemporary discourses about the African content, often accessed via the future… they critique colonialism, paternalism and the ‘white saviour complex’. Do you see this as the role of science fiction, as an important way of thinking about social realities?

In its most intriguing moment, Chris Marker and Alain Resnais’s anti-colonial film of 1953, Les Statues Meurient Aussi, introduced a science fictional element, when they state that “we are the Martians of Africa”. Although for them this reversed the typical Western ethnographic gaze at the Other, in a sense it also stated the obvious about colonial encounters. The West’s command that Africa submit to its rationalized, modernizing perspective already has something of science fiction about it – visitors from another world whose technologies coerce the submission of the visited. So, science fiction doesn’t necessarily offer a different view of reality – it also participates in that reality. To give another example from the show, we mention in the guide that Neill Blomkamp’s mock-advert for a Soweto robot law-enforcer doesn’t so much posit a worrying future trajectory as it documents a present reality. As Mike Davis notes in his book Planet of Slums, Pentagon MOUT strategists – convinced that future wars will be conducted in the slums against the marginalized, informal populations of megacities – are already planning for the extension into Kinshasa and Lagos of recent high-technology incursions into Sadr City (just one example). By pointing this out, we hope to suggest various entanglements between science fiction and documentary – the present as only apprehensible through SF; SF as a means of securing a global trajectory, and more fundamentally, how most of the artists in this exhibition use science fiction to complicate the usual documentarian or ethnographic representations of Africa.

In other words, the ideas and methodologies of science fiction must be considered critically, and we hope this comes across from the show. In some ways a lot of the works in the exhibition – Neil Beloufa’s Kempinski for example – seek to produce a different form of science fiction from that of dominant cinema. Not only by using African scenarios – reasonably unfamiliar territory for SF cinema before District 9. At some level, the big-budget CGI blockbusters turned out by Hollywood are guilty of extending and gilding global relations of dominion and submission. Not only do their narratives simply allegorize problematic current viewpoints within a (semi-)fictional setting, at an infrastructural level the imaging technologies that are essential to their commercial credibility directly descend from imperial military applications, as some of Harun Farocki’s works consider, for example. It is not enough simply to posit SF as a critique, as it takes on so many forms that support those typical expectations – although we wanted to investigate how it might offer space to resist the usual formulations of global discourse.

Do you see futurism and science fiction in contemporary art from and of Africa as a form of defiance?

Yes, in the sense that the dominant images and narratives about Africa portray a continent “mired in the present” – unable to escape recurring crises born of its unresolved histories. The future tense – which foregrounds desire and possibility – avoids these representations, which are mainly reproduced in the interests of global hegemonies. Equally perhaps, these works defy the dominant forms of SF itself, in their avoidance of the big studio system, in their attempt to produce a future that does not simply extend the present, and arguably in their African settings.

In these ways, I think they seek to disrupt the borders of Rancière’s “regime of the sensible” – producing new visibilities, and subjectivizing those who have been excluded from global discourses except, at best, as victims. Then again, we don’t see Wanrui Kahiu’s film, Pumzi (2009) as necessarily defiant, or at least only in the sense that she is a young African filmmaker producing fantasy SF to rival Hollywood, with all of the attendant geographical and budgetary disadvantages. The film itself reworks many familiar tropes of SF – the post-apocalyptic location, the totalitarian control of limited resources, and the desire to escape a futuristic state and return to a natural state, are all well-explored narratives. Perhaps it is the African setting itself which adds the extra traction to this film.

In a sense, there is a defiance of the science fiction genre too. Historically, SF has been used as a means to create allegories that consolidate difference and fear of the Other or the invader. This was very clear in the allegorical science fiction during the Cold War era for example, which aimed to represent the West’s battle with communism and generate collective fear of the unknown. The science fiction aspects in many of these works reconsider the idea of oppositions and threats.

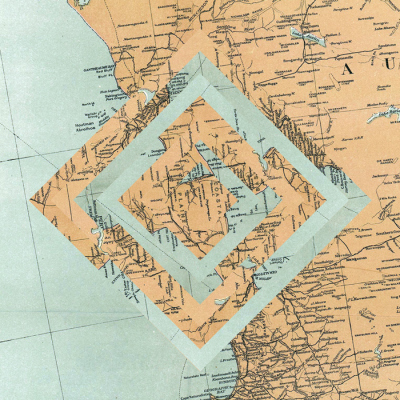

On the ground floor, Luis Dourado’s map [above] and later, Omer Fast’s video installation have been arranged into a kind of labyrinthine maze. It felt to be a very physical way of inaugurating the viewer into the complexities of science fiction and its ideas. Do you agree?

Not really in the sense of the physical experience – this is more or less how Fast’s installation is always intended to be presented. But in conceptual terms, the cut-up map was certainly intended to produce an immediate re-orientation of certain given blueprints – aiming to chart a different reality. We saw its diamond formation more like a portal, or stargate, and for us, this suggested a shift from space into time. This reflects a sense running through our research that, with global space already mapped and conquered (of course, a map is a device of conquest), it is the temporal axis that has become a contested site, as hegemonic forces seek to secure the future for more of the same, whilst others claim it as the possibility of alternative realities. In terms of the art world, the map plots a shift away from the regional representation towards a more complex, refracted viewpoint on Africa. The exhibition is not about African artists. Rather, it seeks to critically approach questions about (regional) representation by bringing together the subject of Africa and SF.

In science fiction itself, as a result of the possibility of reachable life-bearing worlds being unlikely, and in the way that the genre itself has exhausted long-ago the imaginative landscape of other worlds, time also becomes the active principle. So, this map is not so much about making a familiar continent extra-terrestrial, with all the old associations of the Other. Instead, it elevates time over space, disturbing the familiar image-regimes. In another way, and thinking about Omer Fast’s installation, the idea of the cinematic apparatus comes into it. We hadn’t really thought about it as a labyrinth, wondering if it perhaps resembled the sequential waiting-rooms of an immigration office, with flat-screens giving out information (of course, this could have a labyrinthine aspect!) It also, like the MDF viewing structure for Beloufa’s work, seems to disrupt the expected architectural space of cinema, just as it wants to complicate the expected cinematic narratives.

Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction runs at the Arnolfini, Bristol (@arnolfiniarts) until Sunday 1st July.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers