Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 525

August 1, 2012

Sight & Sound’s once-a-decade poll of the greatest films of all time

[image error]

Tonight in London, film magazine Sight & Sound (published by the British Film Institute) announces its once-in-a-decade poll of the greatest films of all time, “perhaps the most recognized poll of its kind in the world.” The poll was first conducted in 1952. Earlier this year they asked about 800 critics, programmers, academics and curators from around the world to make submissions, including yours truly. Below I’ve copied the list I sent in along with my motivations. And yes I included one film with a sports theme. I think probably one or two of my selections made it to the final rankings. I would love to hear your opinions.

My ten films (in no particular order) are:

3. The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On

4. Raging Bull

5. Cassablanca

7. Borom Sarret

9. Mapantsula

10. The Birds

I chose these ten films as they have had the biggest impact on my own view of cinema. Battle of Algiers stands alone as a piece of fictional documentary. I like both Emile de Antonio’s 1968 documentary “In The Year of the Pig” (1968) and Peter Davis’s “Hearts and Minds” as definitive pieces of work on Vietnam (I think Davis used some of de Antonio’s footage). Filmmakers as diverse as Michael Moore and Errol Morris swear by “The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On,” about a Japanese World War II veteran. “Casablanca” (a film set in Africa with hardly any Africans in it), Hitchcock’s “The Birds,” “The Godfather (I)” and “Raging Bull” are all classic films. Finally, I picked two African films knowing full well those won’t probably make it far in the poll, but I feel strongly about their value as cinema. “Borom Sarret” (The Wagoner), an 18-minute film set in newly independent Senegal by Ousmane Sembene. The film is considered the first directed by a black African in 1966. And finally, I decided on including “Mapantsula,” a 1988 film about a gangster-activist made by the black-white South Africa duo of Thomas Mogotlane and Oliver Schmitz and which I consider the definitive film on Apartheid.

July 31, 2012

Take The A Train

I’ve recently taken on a new daily commute from Bed-Stuy to Harlem via the A Train. This route, once celebrated in song by Duke Ellington, was and remains famous for connecting New York’s two largest and most historical Black Communities. Today, both communities retain their importance as cultural nodes for the descendents of Black migrants from the American South, but both have also become central nodes for New York’s newest waves of African immigration. The almost hour long commute has given me plenty of time to get through a few DJ mixes. Given my daily trip’s musical and cultural connection, perhaps it’s only appropriate that I present “Take the A Train” updated for the 21st Century, a list of some of my favorite Africa-connected mixes from this year so far.

Olugbenga’s Africa in Your Earbuds #15 for OkayAfrica

Olugbenga’s Africa in Your Earbuds #15 for OkayAfrica

By far my favorite in the Africa in Your Earbuds series over at OkayAfrica. This schizophrenic but brief mix takes us from Highlife to Grime via Naija pop and Afrobeat, transitioned by Olugbenga’s own productions. The personality that comes out in this mix is something that all mix creators should strive for. Otelo Burning Mixtape

Otelo Burning Mixtape

I haven’t seen the movie, but the mixtape is outstanding. There are plenty of surprising elements and favorite tracks, but standouts include Zaki Ibrahim’s “Something in the Water” and “Walk on Water” by Reason. Both artists are on the lineup of Motif Records. The Jungle Book Beat Tape by DJ Juls

The Jungle Book Beat Tape by DJ Juls

This is a beat-tape, a mix made up of original productions that sample from sources that have influenced the beat-maker. While others have attempted to do similar Dilla-esque sampling of West African sounds, DJ Juls’s The Jungle Book beat tape is by far the best I’ve heard. The mix is perfect to vibe out to while doing something else, allowing oneself to get surprised by the various musical elements he throws in. Check out the great write up on Juls by Benjamin Lebrave at This is Africa. Ngoma 13: Juju-Juke by DJ Zhao

Ngoma 13: Juju-Juke by DJ Zhao

The great thing about the Internet is the ability to give a lot of context to a DJ mix to learn about what inspired the sound, and give background on the artists included. No one does this more thoroughly than Berlin-based DJ Zhao. His latest mix in his Ngoma series “Juju-Juke” is my favorite of his. Zhao expands on an idea I myself have played with, and puts it together into a beautifully executed mix. Afro-House 2012 by Dubbel Dutch

Afro-House 2012 by Dubbel Dutch

I’ve repeatedly said that Angolan House is one of the genres I’m most excited about. Benjamin Lebrave points to a flawless mix by a key figure in the industry, DJ Satellite. But it is an American who put together my favorite mix of African House tunes in 2012 so far. This mix culled entirely from the Soundcloud pages of various producers in Portugal and Angola is a stellar representation of the Kuduro-House sound. The Ultimate Azonto Mix CD by DJ Neptizzle

The Ultimate Azonto Mix CD by DJ Neptizzle

A springtime round up of the best in Azonto sounds via UK DJ Neptizzle. This is probably the most comprehensive round up I’ve heard of the impending Ghanian take-over of the global pop pallette. A great mix to get anyone dancing! Fact Mix 307: Ayshay

Fact Mix 307: Ayshay

This mix officially dropped in 2011, but in December, so I mostly listened to it in 2012. Ayshay is the alias of New York via Dakar via Kuwait producer Fatima Al Qadiri. A deeply personal cross-section of the artist’s Afro-Arab sonic identities, the entire mix is stellar. But it’s the point where Madinina suddenly slips into Medina that made this one of my favorite mixes ever. Yo No Soy Virgen, Pero Hago Milagros by Maracuyeah

Yo No Soy Virgen, Pero Hago Milagros by Maracuyeah

Based on the name and cover of this mix, it already deserves attention. Sonically you get Cumbia, Vallenatos, smashed together with the Dembows and Moombahtons of DJ Rat and Mafe’s DC Latino experience. It’s a formula to create another deeply personal and well put together DJ mix. My only critique comes inspired by my El Salvadoran friend who grew up in DC when it was still “Chocolate City,” who said he wanted to hear Cumbia and Go Go mashed up. Dark York by Le1f

Dark York by Le1f

This mix is one I’m still wrapping my head around. Partly because the Uptown lingo, that Le1f spits mutedly over an amazingly curated selection of futuristic electronic beats from the best of the up and comers in the electronic dance world like Nguzunguzu, Skin and Bones, Matt Shadetek, is taking me a while to fully understand and interpret. Le1f raps fast and continuous around colloquial concepts that will have most of us playing catch up for awhile long after he’s moved on to his next projects. It’s also worth mentioning that Le1f (Khalif Diouf) is a representative of New York’s Senegalese community via Harlem, and that’s a perfect place to end our ride on the A Train. Almost. Don’t forget my own Africa-centered mix from earlier this year over at the XLR8R Podcast!

Don’t forget my own Africa-centered mix from earlier this year over at the XLR8R Podcast!

Africa is a Country is taking a break from blogging during August. We’ll be back in September. Till then, follow us on Twitter or keep up to date via Facebook.

Winter List: Festivals in Southern Africa

Steel-pan soloist Ken Philmore will perform at this year’s Joy of Jazz Festival in Johannesburg

While some in the virtual AIAC office have been putting together their summer lists, I thought I’d keep it real and put up a winter list. (Yes, it’s winter here in South Africa.) If you ever get tired of summer in the Northern hemisphere, this list is for you. While this is by no means a definitive list, all these festivals are worth the travel to get there. Here are my top winter festivals to visit in Southern Africa.

Grahamstown National Arts Festival (South Africa)

Grahamstown Festival, as the National Arts Festival is known locally, is essentially a melting pot of what’s happening in the arts in South Africa, from live shows, to film screenings, to exhibitions. In particular, it’s a great place to see new theatre and live music from around the country. While the festival has some way to go in terms of inclusion (it can be read as a bubble of privilege in a region facing high inequality), it is an important part of South Africa’s cultural landscape. The jazz jam sessions in those cold Eastern Cape nights are nothing short of legendary. The fest has already passed this year (28 June to 8 July) but be sure to check it out next year.

Lake of Stars (Malawi)

Lake of Stars is an international music festival on the shores of one of Africa’s largest lakes, Lake Malawi. According to the festival press release, last year’s festival headlined by Foals was hailed by “the international media” as the “most spectacular festival in the world.” Previous headliners include Zimbabwean musical giant Oliver Mtukudzi, The Very Best and Groove Armada. Started by a British guy called Will Jameson who initially traveled to Malawi to do NGO work, the festival aims to not only bring in cash to the country from international visitors but to improve on Malawi’s ‘brand’ as a country, moving away from representations only focused on famine and AIDS. The festival seems to also place local participation and development at the centre of its ethos, pairing with charities such as the Micro Loan Foundation. I’ve never been, but a friend has described it as “mind-blowing.” I can’t wait to go. Lake of Stars is taking a break this year, but will return in September 2013. Put it on your iCal.

Harare International Festival of the Arts (Zimbabwe)

HIFA is another one of those festivals I always mean to go to but never make it there (I’m a Capetonian, to us Johannesburg is a far-off concept). This year’s festival ran in May and boasted an impressive musical line up including Tumi and the Volume, Ismael Lo, and, of course, Tuku AKA Oliver Mtukudzi. Previous years have seen the likes of BLK JKS and Nneka. The festival extends far beyond music however. It has become somewhat of an island of free speech and artistic expression in Zimbabwe with many of the theatre pieces and visual artworks directly confronting the ills of the Mugabe regime. Like Lake of Stars, the festival aims to bring in tourism and boost Zimbabwe’s economy, but more importantly it serves as a great symbol of National Pride. As Kati Auld recently wrote over at Mahala, “in the context of Zimbabwe’s past, every triumph must be placed carefully in the display case of national memory, and polished often.”

Durban International Film Festival (South Africa)

As a filmmaker, I just had to throw this one in there. DIFF is South Africa’s longest running film festival, and probably the most important film festival in South Africa at the moment. It’s a great mix of social and filmic experiences, and one of the rare moments when Cape Town and Jo’burg get to meet in a neutral space. The last time I was there I got to hang out with my favourite local filmmakers, pitched to international broadcasters, and met some international heavyweights. And somehow I managed to see some films as well. It was a good time. Another plus is that Durban is almost always warm, both in spirit and in climate, even in the middle of winter. This year, DIFF ran earlier this month.

Joy of Jazz (Johannesburg, South Africa)

Finally, a festival on my list that hasn’t passed yet this year. The Joy of Jazz festival is coming up from the 23 – 25th of August in Johannesburg’s hip gentrified inner city Newtown District — although things move so quickly in Jo’burg I’m not really sure if it’s hip anymore. Do people still say “hip”? With each year, it seems as if Joy of Jazz will eventually eclipse the hugely successful Cape Town International Jazz Festival, which takes place in our summer. It seems to poise itself as more of a “strictly jazz” festival, and will feature some international and local heavyweights such as Grammy award-winning Kurt Elling, trombone maestro Wycliffe Gordon, local legends Caiphus Semenya and Bakhiti Khumalo. Also on the bill is Jane Monheit and the hip hop inspired trumpeter Erik Truffaz. And Thandiswa Mazwai, Swazi Dlamini and Vusi Khumalo will be playing a tribute to Winston Makunku, Zakes Nkosi and Joe Malinga. Sounds like a crash course in jazz school. Time to get an education!

July 29, 2012

Summer List: More Readings in New Academic Books

Segregation: A Global History of Divided Cities by Carl Nightingale (University of Chicago Press, 2012) examines the world history of segregation, highlighting the notorious role played by South Africa in dividing communities along racial lines (a central case study is Johannesburg). As Nightingale reminds us, segregation in South Africa began long before it became formally instantiated as apartheid. And while divisions between people in cities goes back to Mesopotamia, the practice became entrenched as part of European colonialism’s urban planning, glaringly depicted, for instance, in the separation between the Casbah and the European quarter in Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers. In his examination of segregation in the United States, Nightingale looks at how division along racial lines continued after the abolition of state-sanctioned segregation laws. Certainly in the second half of the twentieth century apartheid laws were the exception rather than the rule, and it does us well to think about how urban patterns of racial division persist when the state no longer directly enforces them.

Segregation: A Global History of Divided Cities by Carl Nightingale (University of Chicago Press, 2012) examines the world history of segregation, highlighting the notorious role played by South Africa in dividing communities along racial lines (a central case study is Johannesburg). As Nightingale reminds us, segregation in South Africa began long before it became formally instantiated as apartheid. And while divisions between people in cities goes back to Mesopotamia, the practice became entrenched as part of European colonialism’s urban planning, glaringly depicted, for instance, in the separation between the Casbah and the European quarter in Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers. In his examination of segregation in the United States, Nightingale looks at how division along racial lines continued after the abolition of state-sanctioned segregation laws. Certainly in the second half of the twentieth century apartheid laws were the exception rather than the rule, and it does us well to think about how urban patterns of racial division persist when the state no longer directly enforces them.  A difficult but rewarding book, The Event of Postcolonial Shame by Timothy Bewes (Princeton UP, 2011), zeroes in on the shame that inheres for writers in the postcolony when the question, “how to write without thereby contributing to the material inscription of inequality?” remains hard to answer. Focusing on works by a cross-section of writers from the global south, Bewes examines “what possibilities exist for a literary form that might be adequate to the ethical complexity of the postcolonial world” suggesting particularly that South Africans Zoë Wicomb and J.M. Coetzee, as well as the Caribbean writer, Caryl Phillips, address explicitly in their themes, and implicitly in their formal choices, the ethical imperatives at stake after slavery, colonialism, and apartheid.

A difficult but rewarding book, The Event of Postcolonial Shame by Timothy Bewes (Princeton UP, 2011), zeroes in on the shame that inheres for writers in the postcolony when the question, “how to write without thereby contributing to the material inscription of inequality?” remains hard to answer. Focusing on works by a cross-section of writers from the global south, Bewes examines “what possibilities exist for a literary form that might be adequate to the ethical complexity of the postcolonial world” suggesting particularly that South Africans Zoë Wicomb and J.M. Coetzee, as well as the Caribbean writer, Caryl Phillips, address explicitly in their themes, and implicitly in their formal choices, the ethical imperatives at stake after slavery, colonialism, and apartheid. If Bewes is correct that “in a certain strain of postcolonial scholarship informed by Spivak’s conceptualization of the subaltern…the real histories of national liberation in Third World countries disappear into an abyss of epistemological méconnaissance,” Susan Andrade’s book The Nation Writ Small: African Fictions and Feminisms, 1958-1988 (Duke UP 2011) provides a useful corrective. It explores how women writers who wrote during the mass wave of continental decolonization were vitally involved in representations of political realities, despite the simplistic tendency to equate women’s writing with domestic spheres seemingly cut off from the public sphere. Instead Andrade makes clear how writers such as Mariama Bâ, Aminata Sow Fall, Tsitsi Dangarambga, and others, depicted worlds very much inflected by the changing political field, and exposed the disappointments and tragedies of independence as much as its optimism. Including an examination of more recent work by Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Andrade’s book reminds us how much these women’s work informed and continues to inform the language of political debate.

If Bewes is correct that “in a certain strain of postcolonial scholarship informed by Spivak’s conceptualization of the subaltern…the real histories of national liberation in Third World countries disappear into an abyss of epistemological méconnaissance,” Susan Andrade’s book The Nation Writ Small: African Fictions and Feminisms, 1958-1988 (Duke UP 2011) provides a useful corrective. It explores how women writers who wrote during the mass wave of continental decolonization were vitally involved in representations of political realities, despite the simplistic tendency to equate women’s writing with domestic spheres seemingly cut off from the public sphere. Instead Andrade makes clear how writers such as Mariama Bâ, Aminata Sow Fall, Tsitsi Dangarambga, and others, depicted worlds very much inflected by the changing political field, and exposed the disappointments and tragedies of independence as much as its optimism. Including an examination of more recent work by Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Andrade’s book reminds us how much these women’s work informed and continues to inform the language of political debate. Finally, A.B. Xuma. Autobiography and Selected Works (Ed. Peter Limb. Van Riebeck Society, 2012) reminds us of the importance of primary materials for scholarly work on African history. The compilation of works by Alfred Bitini Xuma, president of the ANC from 1940-49, gathers his (mostly) unpublished autobiography along with a variety of other genres, including letters, speeches, eulogies and pamphlets, much of which level overt critiques of the state’s white supremacist segregation policies. Xuma fell out of favor for being less radical than Young Turks such as Mandela and Sisulu of the Youth League. However Xuma, cosmopolitan and nationalist, is finally getting some of the attention he deserves here, as ideological divisions in the early history of the ANC no longer require obfuscation for the sake of presenting a unified political front. In an interview on the Africa Past & Present podcast, editor Peter Limb relates that he hopes the book will “open up more research on a range of issues such as [Xuma’s] life and times, related themes of medical, social and ANC history; the history of African women in politics; intellectual history and social biography…. to facilitate textual analysis in South African historiography and draw attention to the need to develop the study of the genre of the works of black authors.” This book could certainly begin to do this.

Finally, A.B. Xuma. Autobiography and Selected Works (Ed. Peter Limb. Van Riebeck Society, 2012) reminds us of the importance of primary materials for scholarly work on African history. The compilation of works by Alfred Bitini Xuma, president of the ANC from 1940-49, gathers his (mostly) unpublished autobiography along with a variety of other genres, including letters, speeches, eulogies and pamphlets, much of which level overt critiques of the state’s white supremacist segregation policies. Xuma fell out of favor for being less radical than Young Turks such as Mandela and Sisulu of the Youth League. However Xuma, cosmopolitan and nationalist, is finally getting some of the attention he deserves here, as ideological divisions in the early history of the ANC no longer require obfuscation for the sake of presenting a unified political front. In an interview on the Africa Past & Present podcast, editor Peter Limb relates that he hopes the book will “open up more research on a range of issues such as [Xuma’s] life and times, related themes of medical, social and ANC history; the history of African women in politics; intellectual history and social biography…. to facilitate textual analysis in South African historiography and draw attention to the need to develop the study of the genre of the works of black authors.” This book could certainly begin to do this.

A renewed narrative on the non-renewable: Romuald Hazoumé’s Cargoland

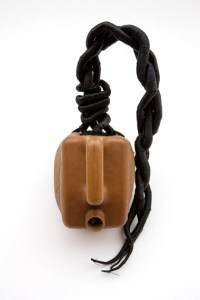

‘Water Cargo’

Guest post by Jonathan Duncan

Romuald Hazoumé’s third solo exhibition at The October Gallery, Cargoland, is a re-appropriated and extended title — a familiar technique for those who follow his work. A play on ‘cargo’, which translates in West African French to mean “anything of weight and value that needs to be transported,” the Cargoland presented within the gallery space is largely commanded by two mixed media installations entitled ‘Water Cargo’ and ‘Petrol Cargo’, two large tricycle scooters re-fashioned to bear the transportation of loads beyond their original design.

First in the gallery, ‘Water Cargo’, which has been redesigned to deliver fresh water, has feathered wings to accommodate its load. Its less avian partner, ‘Petrol Cargo’, which houses petrol vials of decreasing size evoke a memory of antiquated medicinal bottles made for the illegal trafficking of black market petrol — ‘kpayo’ — from Nigeria to the artists home country, Benin. These aged, wrinkled, wrought iron butterflies sit in conceptual opposition. Where ‘Petrol Cargo’ re-iterates the unpalatable consequence and human reality of our reliance on non-renewable fuels, ‘Water Cargo’ predicates an image of the future trade of drinkable water, reminding the viewer that much like the perishing oil reserves being plumbed in Africa and around the world, water may soon also be fiercely fought over.

Both flightless birds command gravity and sit onerously in the mind. Not merely because of the size and imagined mass of the scooter and its cargo, but for both objects representation of entrapment. Both are artefacts of the incessant demand for petrol that lures the driver and maintains them clasped in the illegal channels that distribute this ‘black gold’. It’s a global enslavement by proxy.

In a steely, surgical stare the artist bears witness to the realities of this illegal trade, presented in five panoramic, documentary style photographs. They depict the final destination of the illegal petrol. The photographs are detached; these amputated visions cold and judgmental.

Hazoumé as the bricoleur — the assembler of foraged objects. Further into the gallery, are seven of his recent ‘masks’ that brought the artist into prominence in the U.K. when they were included in the Saatchi Gallery’s show ‘Out of Africa’. Each ‘face’ is assembled from a variety of appropriated petrol vessels, with tightly wound hair woven into their plastic heads. Once the faces emerge, conjured from the blank palette of the white walls, a wry smile is helpless. However, that soon dissolves, as the potency in connotation and intent of the petrol canisters used, demands a secondary contemplation. As the ‘masks’ reconfigure in front of the eye, disheveled and contorted, wheezing rounded vowels from their mouths, the fuel vessels’ form and meaning are compounded, as the space the petrol once occupied is now full with Hazoumé’s commentary on the petrol that was once there.

One of the ‘masks’ was renamed ‘Fukoshima’, ‘out of respect for the pain of the Japanese people displaced by the twin natural disasters of March, 2011′ thereby forging a connection to another site and the horrific consequences of relying on non-renewables, strengthening the artist’s thematic discussion.

Hazoumé’s bond with his community is distinct and present. He takes the role of narrator of his community’s collective and of shared narratives with an ease. The humanism of his artistic practice reveals an indication to his ideas on the artist’s moral responsibility to their society, while simultaneously allowing the viewer to be easily enveloped in the place of the works birth, and his evaluation and subversion. He achieves a robust potency of voice and content while avoiding didacticism, instead warmly encouraging voyage, interpretation and critique. For after all, are these not just another collection of ‘exotic objects’. Hazoumé both addresses and subverts this viewpoint.

Although all the work in the exhibition is saturated with its geographic origin, Hazoumé’s discourse resonates far beyond. ‘As a reminder to everyone that Cargoland really exists — and we all belong to it.’

Cargoland is open till the 11th of August at October Gallery, 24 Old Gloucester Road, London.

Jonathan Duncan (@Tobe_averb) is a writer and designer living in London.

July 28, 2012

Wet Hot African Summer

We’ve scoured the web to bring you the best and worst romance, adventure, intrigue, and kinky fantasies Africa has to offer.

10. Burning Embers by Hannah Fielding

When someone says “Africa” and “romance novel” Burning Embers by Hannah Fielding is the obvious choice. It’s trashy, if a bit timid for our taste.

Burning Embers, published by Omnific Publishing, is a contemporary historical romance novel set in Kenya in 1970. It depicts the developing attraction and love between a young and naive woman, Coral, who has come home to Africa, the land of her birth, and Rafe, a handsome, virile, commanding plantation owner who carries a dark secret heavy in his heart. It is an evocative and passionate story of coming of age, of letting go of the past, of having faith in a person and of overcoming obstacles to love, set against the vivid and colourful backdrop of rural Africa and its culture.

We like

• African women returning home to Africa young and naïve

• Handsome and virile plantation owners

• Unimportant mundane things, blossoming, yearing

• The vivid and colourful backdrop of Africa and its culture

• The title showing up in this scene:

Though the afternoon sunshine was beginning to fade, the air was still hot and heavy. Coral was struck by the awesome silence that surrounded them. Not a bird in sight, no shuffle in the undergrowth, even the insects were elusive. They climbed a little way up the escarpment over the plateau and found a spot that dominated the view of the whole glade. Rafe spread out the blanket under an acacia tree. They ate some chicken sandwiches and eggs and polished off the bottle of wine. They chatted casually, like old friends, about unimportant mundane things, as though they were both trying to ward off the real issue, to stifle the burning embers that were smoldering dangerously in both their minds and their bodies.

All the while, Coral had been aware of the need blossoming inside her, clouding all reason with desire. She could tell that he was fighting his own battle. Why was he holding back? Was he waiting for her to make the first move? Rafe was laying on his side, propped up on his elbow, his head leaning on his hand, watching her through his long black lashes. The rhythm of his breathing was slightly faster, and she could detect a little pulse beating in the middle of his temple, both a suggestion of the turmoil inside him. Rafe put out a hand to touch her but seemed to change his mind and drew it away. Coral stared back at him, her eyes dark with yearning, searching his face.

The shutters came down. “Don’t, Coral,” Rafe whispered, “don’t tease. There’s a limit to the amount of resistance a man has.”

9. The African Queen

…is Audrey Hepburn as a British missionary’s “sister” trapped in German Eastern Africa when the First World War breaks out. When she convinces a wild riverboat captain to attack an enemy warship they face unnaturally bloodthirsty parasites and their own budding romance in stunning Africanesque Technicolor.

Watch the trailer here, then click around for some more scenes.

8. Healing Inc. by Deneice P. Tarbox

Full disclosure—we haven’t read this one, and the publisher’s description is a bit convoluted, but this cover is doing all kinds of things right.

7. Gito L’ingrat by Léonce Ngabo

Virile White men and their delicate counterparts aren’t the only ones finding romance in Africa. Meet Gito, a talented and ambitious Burundi student who goes to Paris to get a sophisticated accent and a cabinet post back. He meets a French woman, falls in love, and promises to send for her as soon as he gets set up at home. But then, it takes a long time to find a job, and soon sparks are flying with his childhood sweetheart. Everything is going fine until the European girlfriend shows up. She is charmed by his rural family life and his parents are happy to have her stay. When two girlfriends find out about each other Gito is taught a lesson he won’t soon forget.

Rent the movie for $5 here.

6. Every Dark Desire by Fiona Zedde

This popular Jamaican lesbian vampire erotica is not strictly set in Africa, but we’re glad to see that Twilight has been written better and without the predatory nobleman.

From the author’s website:

When a sensual encounter under the full moon transforms her into one of the immortal undead, Naomi McElroy, now known as Belle, is trained in the ways of the vampire as she spends her days with her new family, an ancient clan that opens new doors of erotic pleasure for her to explore.

Read the first chapter here.

5. Zulu Heart by Steven Barnes

A Novel of Slavery and Freedom in an Alternate America.

Generations ago, ships from Egypt and Ethiopia sailed west to the New World, bearing African colonists and savage European slaves. But the settlers in the proud young land of Bilalistan are not free from the conflicts of the motherland…

Multiple award-nominee Steven Barnes returns to the brilliantly envisioned world of his acclaimed nove [sic] Lion’s Blood – in which all the complexities and wonders of African civilization have flourished, dominant and unchallenged. Depicting profound evocations of African traditions and Irish-European cultures, Barnes presents a unique, insightful epic of American speculative fiction…

The year is 1294 –or, to Christians, 1877. Egypt’s Pharaoh threatens war against Ethiopia’s Empress and plans to embroil the New World in his cause. While the Northern colonists are subjects of the Pharaoh, Southern revolutionaries are loyal to the Empress.

Caught in the cneter (sic) of the storm is Kai ibn Rashid, married to the Empress’s niece and lord of a vast Southern estate. A senator who only wants peace, Kai is opposed to the Pharaoh’s war — a position that may cost him dearly, for assassins have targeted his family. Meanwhile, the New World’s other major power, the unpredictable Zulu nation, has pressed Kai to accept their princess, the exquisite niece of Shaka Zulu, as his second wife. Tantalized by her beauty, Kai also fears that the princess is a spy with lethal plans.

Now in desperate need of help, Kai summons a childhood friend, the freed slave Aidan O’Dere, to go on a deadly mission. Aidan’s reward is information to save his long-lost sister, Nessa, and safe passage home. Yet to succeed, Aidan must willingly submit himself to the greatest degradation he has ever known — the cruel yoke of slavery.

With war looming and betrayal threatening on every side, failure will mean execution for Kai and Aidan. But will success cost even more? For by challenging the will of the Pharaoh, Kai could be signing his family’s death warrants. And by aiding the South, Aidan could be keeping millions of whites in bondage.

Buy your copy on Black Books Direct.

4. Libyan Lust by James Orr

Popular British romance novelist James Orr takes taken his political romance novels to the Arab Spring.

From the publisher: “James is sent to Libya, North Africa. He finds the Libyans are looking for fun, freedom and sex.”

Libyan Lust is 197 pages of hot gay sex. The first seven pages are full of charming factoids about Libya’s population and history to orient the reader. On page eight our narrator has sex with a guy who works at the hotel:

He stood very close to where I sat and began to turn the pages. From where I was sitting I was at eye level with his crotch. I waited with halted breath trying to detect any movement in his trousers.

Then it happened there was a sudden jump next to his zipper followed by several more. His cock had started to grow. Within seconds, what appeared to be his large cock was fully erect, causing an obscene bulge in his trousers.

“You seem to like the magazine,” I said, unsure of his knowledge of English.

He looked down at me and smiled seductively then looked at his crotch.

* BONUS Orr writes other hot gay sex scenes in such exotic locations as Burma, Egypt, England, The Fertile Crescent, Indonesia, Jordan, Morocco, and Thailand.

** ANOTHER SOLID OPTION: The Lower River by Paul Theroux:

Ellis Hock never believed that he would return to Africa. He runs an old-fashioned menswear store in a small town in Massachusetts but still dreams of his Eden, the four years he spent in Malawi with the Peace Corps, cut short when he had to return to take over the family business. When his wife leaves him, and he is on his own, he realizes that there is one place for him to go: back to his village in Malawi, on the remote Lower River, where he can be happy again.

Arriving at the dusty village, he finds it transformed: the school he built is a ruin, the church and clinic are gone, and poverty and apathy have set in among the people. They remember him—the White Man with no fear of snakes—and welcome him. But is his new life, his journey back, an escape or a trap?

3. Coup de Torchon by Bernard Tavernier

Coup de torchon (Clean Slate) is adapted from Jim Thompson’s 1964 pulpy Pop. 1280. Lucien Cordier is a chief of police who can’t get any respect in a French West Africa town. His wife berates him and he can’t control the unsavory activities of either Black criminal agents or lazy, sexy White people. But a man can only take so much before he becomes an angel of vengeance…

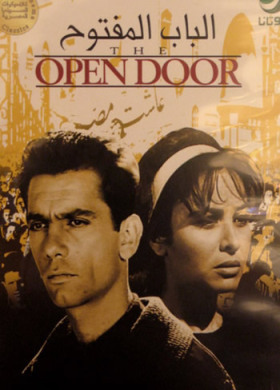

2. The Open Door by Latifa al-Zayyat

Nationalists usually love women symbolically, but this is a more thoughtful and sexy account of changing sexual mores in revolutionary mid-century Egypt. Layla’s father is humiliated when his daughter starts menstruating and vows to marry her off to her cousin. She becomes active in the Suez Canal war in 1956, and gains the courage to call off her conventional engagement to pursue another kind of relationship with a revolutionary colleague.

1. In Darkest Africa by JJ Argus

Publisher’s description:

Kristin is an ambitious and studious California grad student in archeology delighted at being allowed to accompanies a dig searching Ethiopia for a lost palace. But disaster strikes, trapping all the other members of her expedition in a cave-in. Only Kristin is left alive, with very little water, in a small cave on the edge of the desert. Dehydrated and barely conscious, she is found by primitive Ethiopian tribesmen who see in her beautiful golden hair and flawless white skin, the chance for great profits for their poor village. Using ancient tribal potions and skilled caresses, keeping her dehydrated and suggestive, the villagers careful treatment condition her body and mind to helpless, incredible pleasure. Unable to communicate with the backward villagers, naked and helpless, Kristin gives herself to a pleasure so intense her mind can hardly stand it. Sapped of her will to resist, she is slowly turned into a sexual slave, a carnal creature of uninhibited sexuality and lust, and eventually sold to a local trader for transport to the distant city and its decadent princes.

Buy your copy on Amazon, Modern Erotic Library doesn’t seem to have its own site.

July 27, 2012

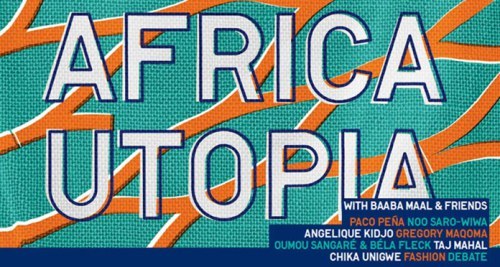

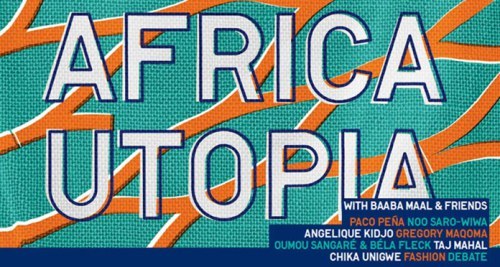

Africa Utopia and London’s “Festival of the World with Mastercard”

The London Olympics starts tonight and certain streets of the city are swollen with purple-shirted volunteers, track-suited athletes and tourists. In Hyde Park, the continent of Africa has been reincarnated as ‘Africa Village’ and ‘Africa Land’; the emphasis is on colour and diversity, mass acceptance of bland positivisms, but the whole event feels mainly about corporate sponsorship. The views are familiar from world fairs in Europe’s colonial capitals, but a different kind of colonizing force is dilligently at work. The ‘renovation’ of London’s east end in advance of the Olympics has been accused of the destruction of historic buildings and common land, the displacement of working-class neighbourhoods in the inscrutable advance of gentrification. Locals have been wondering whether libraries and sports fields lost under our Conservative government might have been a better waste of funds than stadiums which will never again be filled. The media has been arrested by the failure of the security contractors G4S (‘Securing Your World’) to provide the agreed number of security guards, and the armed forces have flooded into London to replace them. This is notable only for the fact that the three G4S ‘escorts’ – in whose unpleasant company Jimmy Mubenga, an Angolan refugee being deported from the UK suffered a mysterious death – have recently been told they will not face a criminal trial for ‘insufficient evidence’. Despite any possible concern, Danny Boyle’s opening ceremony promises to make the effacement of local community by global capitalism an unavoidable spectacle.

Nowhere is this more visible than at the Southbank, the perpetual carnival which happens along the river between Westminster and London Bridge. In tune with this summer’s sporting events the cultural institutions of the Southbank, mindful of their regulators and paymasters on the facing bank of the river, have scheduled “The Festival of the World with Mastercard”, to celebrate the nations competing in the games. Great Britain is no longer the superpower it once was, and in order to maintain its unfeasibly high position at the dining tables of international diplomacy, London is constantly rebranding itself as a ‘world city’, full of global culture, in which the world’s financial elite can live, puffing away at the property market bubble. The British Library, another offender, currently sells itself as a bank of ‘the world’s knowledge’. The attempt to remake the world in England’s image is familiar throughout the history of the British Empire – The Globe Theatre opened on the Southbank in 1599, when English colonialism was first being plotted by the nation’s mapmakers. We wrote about the little boat which overlooks the river from its perch on the Queen Elizabeth Hall, and from the public walkways you can occasionally see lucky individuals standing on the little deck, bemusedly trying to enjoy the experience, like accidental extras in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

A subdivision of “The Festival of the World with Mastercard” is “Africa Utopia”, which has been taking place at the Southbank Centre and Queen Elizabeth Hall over the last month. Contrived by the Southbank Centre to capitalise on the coincidence of (Sub Saharan) African performers in their summer programme, and led in spirit by Baaba Maal, the festival aimed to prove that arts can show the way for social change. The music programme seems packed with acts. One highlight was Saturday night’s Afrobeat evening, and this performance by Nigerian club favourite Brymo.

Mindful of making predictable exclusions, and very conscious of the need to diversify their usual demographic of white British middle-classes, the Southbank organisers devised a youth delegate scheme to invite 10 youths from Africa and 20 from the UK and invite them to discuss art and social change in Africa. I took up, with some awkwardness, an invitation to speak to the delegates as a representative of AIAC. I used the opportunity to rehearse some predictable suspicions about a “Festival of the World with Mastercard”, wondering how the whole world is available to us in London. I attempted, as Evelyn Owen did on this blog (here) to consider the odd premise of Africa Utopia: why use a concept ushered into a troublesome existence in Western political thought by Thomas More’s speculative Latin fiction 500 years ago to think about the histories and contemporary realities of the African continent and diasapora? The youth delegates are a fascinating group of individuals whose various projects are too numerous to mention here. They are aiming to produce a publication as the culmination of their programme (more on that soon, hopefully).

Africa Utopia organiser Hannah Pool gathered some noteable speakers in the ‘Front Room’ of the Queen Elizabeth Hall – swathed in African fabrics – to discuss film, art, politics and development. AIAC’s own Basia Lewandowska Cummings convened a panel on Nollywood and financial models for film industries. Granta Magazine organised a ‘literary salon’ with three novelists, including Numbi organiser and writer Diriye Osman, who gave a brave and exuberant reading. There was a discussion of the We Face Forward exhibition of African art in Manchester (a post on that soon). Tiwani Contemporary curated a panel discussion about Africa and the contemporary art market. The events (which were all free and unticketed) took place in front of large audiences of engaged and vocal individuals, some appeared to have simply walked in straight off the street. This is a rare thing to find on the Southbank. Sunday evening came to a beautiful conclusion with a set by Miryam Solomon. They promise Africa Utopia will happen again next year; we only hope that they consider using a different name.

Africa Utopia and the “Festival of the World”

The London Olympics starts tonight and certain streets of the city are swollen with purple-shirted volunteers, track-suited athletes and tourists. In Hyde Park, the continent of Africa has been reincarnated as ‘Africa Village’ and ‘Africa Land’; the emphasis is on colour and diversity, mass acceptance of bland positivisms, but the whole event feels mainly about corporate sponsorship. The views are familiar from world fairs in Europe’s colonial capitals, but a different kind of colonizing force is dilligently at work. The ‘renovation’ of London’s east end in advance of the Olympics has been accused of the destruction of historic buildings and common land, the displacement of working-class neighbourhoods in the inscrutable advance of gentrification. Locals have been wondering whether libraries and sports fields lost under our Conservative government might have been a better waste of funds than stadiums which will never again be filled. The media has been arrested by the failure of the security contractors G4S (‘Securing Your World’) to provide the agreed number of security guards, and the armed forces have flooded into London to replace them. This is notable only for the fact that the three G4S ‘escorts’ – in whose unpleasant company Jimmy Mubenga, an Angolan refugee being deported from the UK suffered a mysterious death – have recently been told they will not face a criminal trial for ‘insufficient evidence’. Despite any possible concern, Danny Boyle’s opening ceremony promises to make the effacement of local community by global capitalism an unavoidable spectacle.

Nowhere is this more visible than at the Southbank, the perpetual carnival which happens along the river between Westminster and London Bridge. In tune with this summer’s sporting events the cultural institutions of the Southbank, mindful of their regulators and paymasters on the facing bank of the river, have scheduled “The Festival of the World with Mastercard”, to celebrate the nations competing in the games. Great Britain is no longer the superpower it once was, and in order to maintain its unfeasibly high position at the dining tables of international diplomacy, London is constantly rebranding itself as a ‘world city’, full of global culture, in which the world’s financial elite can live, puffing away at the property market bubble. The British Library, another offender, currently sells itself as a bank of ‘the world’s knowledge’. The attempt to remake the world in England’s image is familiar throughout the history of the British Empire – The Globe Theatre opened on the Southbank in 1599, when English colonialism was first being plotted by the nation’s mapmakers. We wrote about the little boat which overlooks the river from its perch on the Queen Elizabeth Hall, and from the public walkways you can occasionally see lucky individuals standing on the little deck, bemusedly trying to enjoy the experience, like accidental extras in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

A subdivision of “The Festival of the World with Mastercard” is “Africa Utopia”, which has been taking place at the Southbank Centre and Queen Elizabeth Hall over the last month. Contrived by the Southbank Centre to capitalise on the coincidence of (Sub Saharan) African performers in their summer programme, and led in spirit by Baaba Maal, the festival aimed to prove that arts can show the way for social change. The music programme seems packed with acts. One highlight was Saturday night’s Afrobeat evening, and this performance by Nigerian club favourite Brymo.

Mindful of making predictable exclusions, and very conscious of the need to diversify their usual demographic of white British middle-classes, the Southbank organisers devised a youth delegate scheme to invite 10 youths from Africa and 20 from the UK and invite them to discuss art and social change in Africa. I took up, with some awkwardness, an invitation to speak to the delegates as a representative of AIAC. I used the opportunity to rehearse some predictable suspicions about a “Festival of the World with Mastercard”, wondering how the whole world is available to us in London. I attempted, as Evelyn Owen did on this blog (here) to consider the odd premise of Africa Utopia: why use a concept ushered into a troublesome existence in Western political thought by Thomas More’s speculative Latin fiction 500 years ago to think about the histories and contemporary realities of the African continent and diasapora? The youth delegates are a fascinating group of individuals whose various projects are too numerous to mention here. They are aiming to produce a publication as the culmination of their programme (more on that soon, hopefully).

Africa Utopia organiser Hannah Pool gathered some noteable speakers in the ‘Front Room’ of the Queen Elizabeth Hall – swathed in African fabrics – to discuss film, art, politics and development. AIAC’s own Basia Lewandowska Cummings convened a panel on Nollywood and financial models for film industries. Granta Magazine organised a ‘literary salon’ with three novelists, including Numbi organiser and writer Diriye Osman, who gave a brave and exuberant reading. There was a discussion of the We Face Forward exhibition of African art in Manchester (a post on that soon). The events (which were all free and unticketed) took place in front of large audiences of engaged and vocal individuals, some appeared to have simply walked in straight off the street. This is a rare thing to find on the Southbank. Sunday evening came to a beautiful conclusion with a set by Miryam Solomon. They promise Africa Utopia will happen again next year; we only hope that they consider using a different name.

Summer List: Paris is a Continent

What’s good in Paris this summer? Its airwaves of course. Featuring Kamelanc’ (born in Oujda, Morocco) and Atheena (representing Senegal) for example, with ‘Pas besoin’:

Or Orelsan (born in Alençon, France). ‘La terre est ronde’:

Kayna Samet’s (born in Nice, France) ‘Ghetto Tale Remix’ feat. Youssoupha (born in Kinshasa, DRC), Médine (representing Algeria) and Leck (Mokobé’s protegé):

Alonzo (né Kassim Djae d’origine comorienne, in Marseille, France). ‘Avoir une fille’:

Princess Sarah prefers autumn over summer:

Collectif Métissé’s (many nationalities here but based in Bordeaux) summer tune ‘Z dance’ (I wouldn’t mind if we forgot about it by autumn):

M.A.S (né Malik, representing Morocco) riffs off Lil Wayne and Bruno Mars’ ‘Mirror’ in his ‘Des regrets’:

Kenza Farah’s (born in Béjaïa, Algeria) ‘Quelque part’:

Tal (representing Yemen and Israel) featuring Mokobé (representing Mali) on ‘Je prend le large’:

And there’s Matt Houston’s (born in Sainte-Anne, Guadeloupe) collaboration with Nigerian duo P-Square:

July 26, 2012

More than one specter haunts South Africa

This week, the World Bank issued a report, South Africa Economic Update: Inequality of Opportunity. The report accurately and unsurprisingly details the depth of inequality in the new South Africa. For some, this report, and even more inequality itself, proves that “the spirit of Verwoerd still haunts” the nation. For others, the report details a present day threat to the future, a future that should be one of growth. For others, it’s something of a mix of national and global. A global sluggish economy takes a special form in a nation marked, perhaps constituted, by “a yawning gap between the nation’s richest and poorest citizens”.

Everywhere the reports comment on the persistence and roots of this inequality. Rightly so. As some note, the report itself identifies the subjects of the inequality: “In addition to being young and living in certain locations, being a woman and non-white still matters, increasing the likelihood of being unemployed or underemployed significantly (over and above any impact of these attributes on education).policy—one of the rare policy goals on which a political consensus is easier to achieve.”

Elsewhere, the report suggests, “Whether a person is born a boy or a girl, black or white, in a township or leafy suburb, to an educated and well-off parent or otherwise should not be relevant to reaching his or her full potential: ideally, only the person’s effort, innate talent, choices in life, and, to an extent, sheer luck, would be the influencing forces. This is at the core of the equality of opportunity principle, which provides a powerful platform for the formulation of social and economic policy—one of the rare policy goals on which a political consensus is easier to achieve.”

As far as the report goes, it’s fine. The data seems more or less reasonable and in line with many other reports on inequality in South Africa. The history, however, has one glaring omission. The World Bank itself. Nowhere in a report on the roots and persistence of inequality in South Africa is there any discussion of the role that the World Bank, the IMF, and other powerful multinational agencies played in the development of South African economic policies, from Kempton Park to Mangaung and beyond.

If this report suggests that South Africa is still haunted by the spirit of Verwoerd, it also suggests, by omission, other specters must be named as well, starting with the authors of the so-called Washington Consensus.

* About the video. As Equal Education members and supporters from across South Africa gathered at the movement’s first national congress in Johannesburg last week, the question of what it means to be an “equaliser” was front and center. In the video, five learners [from Khayelitsha] from Equal Education’s Social Activism and Documentary Filmmaking workshop reflect on their experiences as equalisers. This was also their first time producing, filming and editing interviews. [The learners were trained by students from The New School—Palika Makam, Jordan Clark and Carlos Cagin—who are in South Africa for two months supervised by AIAC's Sean Jacobs.]

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers