Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 521

September 23, 2012

My favorite photographs N°7: Aida Muluneh

Ethiopian Aida Muluneh is one of the hardest working and most talented photographers I have ever met. Identifying African female photographers who document the continent is worth a PhD thesis due to the amount of research that will be required to find them. Aida breaks the mould and lives in Addis Ababa where she founded D.E.S.T.A (Developing and Educating Society Through Art), an organization that promotes cultural development through the use of photography by providing workshops, exhibitions and creative exchanges. Her photography book Ethiopia: Past/Forward (Africalia, 2009) explores Ethiopia through the lenses of identity, personal journey and family nostalgia after a 30-year absence. Her work has been exhibited at the National Museum of African Art in Washington, DC and other venues including some in Cuba and Senegal.

Aida Muluneh: It is difficult for me to select my five favorite photos because each image I have ever shot, mind you since the age of 16, is embedded in my memory like a reminder of my various developments in photography. However, since the start of my career, I knew that my main obsession was with documenting people as opposed to getting into commercial photography or any other type of photography. When I returned to Ethiopia in 2007, I spent a great deal of time documenting people in their surroundings as they worked, prayed, played and so forth. I guess in a way I was creating a collection of missing memories of a country that I never knew growing up. Eventually, the images became a book called Ethiopa: Past/Forward, which was a look at my country through a perspective of nostalgia. Here are, with the exception of the first one above, some of the images from the book:

The World is Nine (acrylic paint and ink drawing on photo paper, 2012)

I had taken the above photograph one sunny afternoon in an area called Bole as I was coming back from the grocery store. The wall was a striking orange from a newly constructed hotel and shopping center. As I was rummaging through my archives I found this image, which really didn’t have a place in my collection. However, when I started doing my line drawings, it was a perfect fit. The process of drawing on the photograph is something that I had in mind a few years ago. I have been doodling these line drawings for a long time and as I tell people, for some unexplainable reason they bring me joy. The process is quite long and requires some form of focus but I find myself at peace when I am doing this work. I have created a few pieces that were exhibited recently but I still feel attached to continuing with my black and white photography. The title is a saying that my grandmother always says…that basically, the world isn’t perfect.

Woman at Doorway (Dese, Welo, Ethiopia, 2008)

I spent almost a week in the city of Dese, Welo waiting for the rains to pass. It was a frustrating period because it was raining heavily most of the day and the little sun that I could find only came towards the end of my stay in the city. In Dese, I had decided that I would document the Muslim community in the country, so in my month long tour of the country, I spent a great deal of time looking for Muslims. By coincidence, I was taken to this old woman’s house; she was a widow and had no means of earning an income. Her eyesight was failing and her husband did not leave much behind for her. I entered her humble home and the first thing that I noticed was the fact that she had an egg on her bed. I decided to shoot the bed and as I looked up I saw this amazing ray of light enter her darkened house through the doorway. I asked her if I could take a photo of her and hence, this was the image created.

It was not until after I had loaded the picture on my computer that I saw the beauty, sadness and I am sure the many stories that this woman carries on the lines of her face. I still think about this woman and often wonder how she is doing.

Past/Forward (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2008)

Originally the chair that the palace security guards used during the reign of Mengistu Hailmamriam. I found it in the home of Prof. Andreas Eshete and thought it symbolized basically the story of a generation. The rule of the Dereg under the leadership of Mengistu Hailmamriam was a period for us that was marked by the massive exodus of a population in order to escape the oppressive system.

This chair to me is fascinating in the sense that whomever was using this chair decided that instead of painting over the Emperor’s emblem (you can see the crown and cross), they chose to stencil the communist symbol of the sickle and hammer.

The Road to the Art School (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2008)

When I first arrived in Addis Ababa in 2007, one of the first things that I did was teach photography to a group of art school students. In their first week of the workshop, they spent a few days shooting along this road that led to the art school, which is part of Addis Ababa University. This small side road that is marked by cobblestones was a short cut for many of the students and they had an interesting relationship with the community.

For me personally, over the years I have seen the neighborhood kids growing up and the various old residences still waling back and forth on this road. In this image, the shadows are the students along with myself and the little kid came out of nowhere chasing a ball. I took the shot because I like the shadows but later on in retrospect I realized the kid reminded me much of my first son.

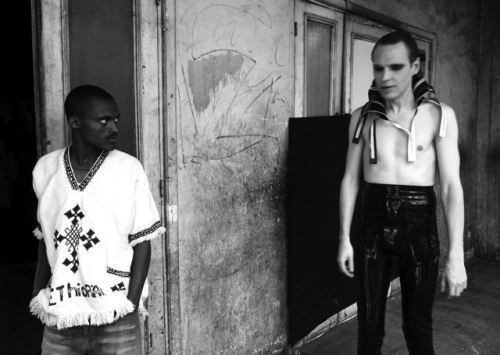

The Look (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2008)

Sometimes when you are shooting, you have to expect the unexpected. This is one of the funniest images that I have in my collection because it is a statement about who we are as a group of people. I cannot remember the full details of the event but it was a performance that took place at Asni Gallery a few years back.

The invited guests came from Sweden and gave various performances in the gallery. When this man came, I could see the looks of the audience because he was wearing high heels along with this outfit. As he did his performance, people were trying to comprehend the whole situation. After he completed his piece, he walked out and it was at this moment that I took this photo. For me there are many things in this image that symbolizes the country. The fact that the guy is wearing a traditional shirt that says Ethiopia, his suspicious glance, and the fact that he is standing at a doorway. Need I say more?

September 21, 2012

Friday Bonus #MusicBreak

Yes, I’ve been listening to pop music a lot. You get work done and don’t have to think too much. First up above is Nairobi’s Camp Mulla and their generic rap pop. Nigeria’s Iyanya presents “Ur Waist.” Yes, he could not have been more obvious:

More Nigerian pop: “Fine Lady” by Lynxxx (featuring Wizkid) with its brief Fela sample.

Might as well get continental here. Congolese pop from Shakalewe:

… and Zambian pop from B1 and Debra:

Congolese-French rapper Youssoupha pays homage to his father — 1970s Congolese rumba star Tabu Ley Rochereau (Google him if you don’t know):

Cane Babu and Young Starz Basagalamanya Squad from the Ugandan capital, Kampala, where the desperate ruling party puts forward 19 year olds for election to Parliament:

Second generation Cape Verdean migrants to The Netherlands shout out Nelson Mandela and the modern state’s founding father Amilcar Cabral:

The Ghanaian-German singer Y’akoto, all neo-soul, with “Good better best”:

And Brooklyn-based Kilo Kish shot this video around Manhattan:

* Bonus: I’ve blogged about this South Sudanese immigrant rapper (more marketing genius) based in Australia before:

When Rick Ross filmed a music video in a Lagos slum

Outsized American rapper (and music executive) Rick Ross shot the latest version of his “Hold me Back” song mostly in Obalende, a poor section of Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital. The video — which resembles the travel diaries shot by rappers on tour — is a strange mix of images and ideas over a nonsensical rap. Shot in black and white, it opens with grainy late 1960s footage from a US television news show of the Biafran War in which a general of the Nigerian Federal Government declares himself pleased with the war’s outcome. It then cuts to a series of disconnected images (Nigerians in a mosque, goats, expensive wrist watches, children crying, a man washing his feet, theater performers on a boat, Ross handing out money to children, more poverty, etcetera) while shirtless Ross raps obscenities (“Niggas” and “bitch” feature heavily). Ross declares that Lagos “holds me back.” The music video ends with grainy images of the Nigerian national football team’s greatest moments — in the 1994 World Cup in the United States and the 1996 Gold Medal performance against Argentina in the Olympic final.

It’s unclear what Ross — who has featured a music video with Nigerian pop stars before and has traveled elsewhere on the continent — or the directors of the video, listed as DRE Films & SpiffTV Films, tried to say with this video. Is it a statement against Igbo claims about the Biafran War in which nearly 3 million people lost their lives? (Boima says he is certain Ross doesn’t really know anything about Biafra.) Or is this about Ross being a fan of soccer now, especially of the Nigerian national team?

What we do know is that Ross shot a previous version of this music video for the song in New Orleans; Ross’s reason then was that he wanted to show that city’s reality for its poor. (In the New Orleans video at least, one of the extras, a local, complains that the government built some inadequate housing for $2 million.) That version of the video was banned by the American channel BET.

As usual the Internets aren’t very helpful. Most websites, especially music blogs, posted the video with no or minimal context and asked their readers to interpret it. The comments on sites frequented by US rap fans are of especially poor quality. More helpful are those on Nigerian blogs (like Nairaland and Linda Ikeji’s) or tweets by Nigerians on Twitter. The condemnation and praise for Ross is evenly divided. Here are some samples from the 200 odd comments to a post of the video (again, with little interpretation or context) on Linda Ikeji’s blog:

This is SO DISGUSTING, are we at war, why are we portrayed as barbaric. FAT RICK ROSS, go to hell.

look at the dirty area the video was shoot. nawah o. i wonder what will be going through G.O.O.D Music acts mind. Rick ross is wicked for shooting his video in a place like this. Fat Fool

my prayer is that lightening will strike rick ross and hailstones will wipe out his entire family even to generations yet unborn.

Some appreciated Ross’s choice of location:

I felt so sad watching this video!!! Everything wrong with/ in Nigeria was shown!!! Nigeria needs a revolution!!! Am so tired of the suffering pain and injustice…… Kudos to rick Ross for highlighting this and remaining us to act n do something about our country.

So Sad. Nigerian artist need to stand against this humiliation. Does D’banj have the guts to go the dark Brooklyn or Michigan, or even the hoodest downtown Baltimore to go shoot a video. Idiots.

Separately a commenter noted on YouTube (to a version of the video posted on WorldstarHipHop’s account and since removed because of a copyright claim):

I don’t really like Rick Ross, or care for his music. However, I have to give him some credit for doing a video of Nigeria which presents the rugged parts of Nigerian society, without passing judgment on it. I’ve never seen D’Banj or P Square do anything like that (who are indigenous Nigerian artists) – they’re too busy copying US music industry cliches instead … there’s nothing in the video or title which suggests he’s intending to represent the whole of Naija. Nigerians should stop constantly complaining at people who present ‘the bad side’ of Naija, especially if they’ve done nothing to help correct it. If our government, society and economy was competent, then much of these images of poverty wouldn’t exist to be filmed.

The negative reaction against Ross is understandable, though misplaced (and boring). It’s like the cottage industry calling for “positive” news about “Africa” in Western media. But equally problematic are those praising Ross for “exposing” poor conditions in Lagos when Ross is merely using Nigeria as a backdrop to make him look hard: “We’re so hard we throw dollar bills off boats to poor kids in Nigeria.” And the references to the Biafra war and old soccer games are baffling. If he was trying to show how Nigerians are struggling with poverty or resisting their conditions, why not use more recent/relevant images like Occupy Nigeria?

After all this, I still think the best retort to Ross comes in the form of comedy:

* Dylan Valley, Boima Tucker, Elliot Ross and Olajumoke Verissimo contributed to this post.

September 20, 2012

We get into the party business

September 19, 2012

10 African films to watch out for, N°3

‘O Grande Kilapy’ (“The Great Kilapy” — ‘kilapy’ is Kimbundu for ‘scheme’, or ‘fraud’), the new film by director Zézé Gamboa, portrays the last decade of Portuguese rule in Angola through the story of Joao Fraga (played by Lazaro Ramos):

The film’s facebook page has some clips. Also check this production video for the images and footage that helped the makers recreate the Angolan ’70s atmosphere.

‘Los Pasos Dobles’ (“The Double Steps”) by Isaki Lacuesta is set in Mali with most of the dialogue in Dogon and Bambara. The story is somehow inspired by the life of writer and painter Francois Augiéras. An ominous trailer, but Lacuesta’s previous poetic work has always been no less than interesting:

(From the same filmmaker, there is also ‘El Cuaderno del Barro’, a documentary about the Spanish artist Miquel Barceló, which serves as a counterpart to — the making of — ‘The Double Steps’.)

‘Les Pirogues des Hautes Terres’ (literally: “the small boats of the highlands”; the film’s official English title is ‘Sand’s Train’) by Olivier Langlois is a made-for-TV production but has been showing at some recent film festivals — and getting good reviews too. It tells the story of the 1947 Senegalese railroad workers strike which set in motion various anti-colonial movements:

(For those interested in the making of the film, I came across these snippets.)

Kenyan “gangster” movie ‘Nairobi Half Life’ is making waves in Nairobi at the moment:

‘Jajouka, Quelque Chose de Bon Vient Vers Toi’ (“Jajouka, something good comes to you”), is a film by Eric and Marc Hurtado, set in the village of Jajouka (in the Rif Mountains of Morocco) featuring Bachir Attar and his “Master Musicians of Jajouka”. The inspiration for the film are the fertility rites led by Bou-Jeloud, a Pan-like “Father of Skins”:

And then some documentaries.

‘Stitching Sudan’ is a film by Mia Bittar about four Northern Sudanese characters from Khartoum who set out on a road trip to discover their newly separated country:

‘Brussels-Kigali’ is the latest film by Marie-France Collard. In 2009, a Belgian Court tried in absentia Rwandan Ephrem Nkezabera, one of the leaders of the Interahamwe militias. Collard was able to film the case and the surrounding debates. With victims and persecutors continuously crossing each others’ paths (both in Rwanda but also abroad), questions are asked about the possibility of mourning, reparation and justice. No trailer as yet, but you’ll find a fragment here.

‘Brussels-Kigali’ is the latest film by Marie-France Collard. In 2009, a Belgian Court tried in absentia Rwandan Ephrem Nkezabera, one of the leaders of the Interahamwe militias. Collard was able to film the case and the surrounding debates. With victims and persecutors continuously crossing each others’ paths (both in Rwanda but also abroad), questions are asked about the possibility of mourning, reparation and justice. No trailer as yet, but you’ll find a fragment here.

‘La Khaoufa Baada Al’Yaoum’ (“No More Fear”) is a feature documentary by Mourad Ben Cheikh about the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia:

In ‘La Vièrge, les Coptes et Moi’ (“The Virgin, the Copts and Me”), French-Egyptian filmmaker Namir Abdel Messeeh goes to Cairo to investigate the phenomenon of miraculous Virgin Mary apparitions in Egypt’s Coptic Christian community. A subtitled fragment, and the trailer (in French, but I’m hopeful it will be soon available in English as well):

And written by Réunion-born Jean-Luc Trulès, “Maraina” is said to be the first ‘Opera from the Indian Ocean’: it tells the story of ten Malagasy and two Frenchmen who left from Fort-Dauphin, Madagascar for Réunion Island in the 17th century to plant and farm tobacco and aloes. The film traces the opera cast’s journey back from Réunion to Madagascar, via France:

Bonus: Maraina, the opera.

Yasiin Bey plays a mbira …

This was done for GQ Magazine. He also raps half-heartedly. I suppose, we should be “tril(led).” He should’ve asked Shabazz Palaces* about what you can do with a mbira:

* BTW, watch out for Shabazz Palaces’ new mixtape next week.

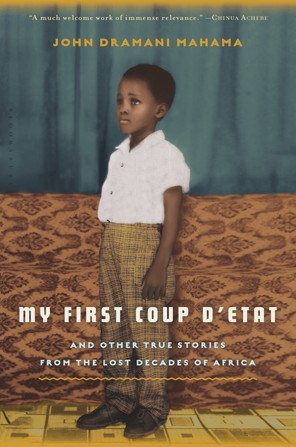

Michael Jackson in Tamale: The memoir of Ghana’s new President

For two decades Ghana has been celebrated for its democratic politics, on-schedule elections and peaceful transfers of power. The record contrasts with the country’s prior instability, going back to the 1966 coup that unseated Kwame Nkrumah, a blow to pan-Africanist dreams and the event that opens John Dramani Mahama’s memoir My First Coup d’Etat: And Other True Stories from the Lost Decades of Africa (Bloomsbury).

For two decades Ghana has been celebrated for its democratic politics, on-schedule elections and peaceful transfers of power. The record contrasts with the country’s prior instability, going back to the 1966 coup that unseated Kwame Nkrumah, a blow to pan-Africanist dreams and the event that opens John Dramani Mahama’s memoir My First Coup d’Etat: And Other True Stories from the Lost Decades of Africa (Bloomsbury).

Back then, Mahama was a nine-year-old boy, returning to the family home to find it surrounded by soldiers, and his father, a Nkrumah official, taken away. Today, Mahama is Ghana’s president, the beneficiary of its latest orderly transition. This one took place not via election, but with the death in office of President John Atta Mills, on July 24 this year. Mahama, the vice president, took over as the constitution mandated. A previously little known figure, he was suddenly front and center—and also suddenly more knowable, as the memoir had appeared just a few weeks earlier. Days before events lifted him to the presidency, Mahama was on a book tour in the US, speaking at the Schomburg Center in New York City and appearing on NPR, where the host asked him to read a passage about an encounter, as a child in his mother’s village, with a snake.

Mahama is Ghana’s first president born after independence, in 1958. But more significant to him, at least in his teenage years in the northern city of Tamale, was that he was born only three months after Michael Jackson. That, plus the fact that they both came from big families, felt like kinship: “I had more in common with Michael Jackson than any of those boys who purposely spoke in awkwardly high voices or stood in front of the mirror every morning and diligently picked their Afros,” Mahama writes. In the early 1970s, upcountry Ghana was caught up in the “cultural exchange taking place between black America and West Africa”—while dashikis proliferated in US streets, “we in Ghana had taken to wearing hipsters, miniskirts, and polyester shirts that were left unbuttoned straight down to the navel.” But the music, Mahama writes, was the “main event.” Motown and Stax were the rage. The 1971 Soul to Soul festival brought Wilson Pickett, Roberta Flack and many others to Black Star Square in Accra. Young Mahama didn’t make the trip, but the provincial discos relayed the energy, and it wasn’t long before Mahama’s older siblings were forming their own bands, Frozen Fire and Oracles 74.

Those were good days. Mahama’s father, E. A. Mahama, had rebounded, having survived the post-Nkrumah purge. At first, he had sought ways to make himself useful in Accra but confronted Ghana’s notorious regional prejudice against northerners; in Mahama’s delicate phrasing, “the south wasn’t being especially welcoming to him in his attempt to start anew.” The father’s decision to go back to Tamale, which Mahama frames as an act of sankofa, looking back so as to better move forward, brought rewards. The elder Mahama set himself up as a farmer and moved into agribusiness, growing and processing rice for the national market and even export. He became, Mahama says plainly, “enormously wealthy.” The children benefited: “He liked for us to have all the things that he did not have while he was growing up … He especially indulged us in our love for music, buying us top-of-the-line music systems … He even bought us a little convertible MG so that we could zip around town.”

But a darkness was looming. General I. K. Acheampong’s regime, for a time viewed as somewhat benevolent or at least pragmatic, was hardening and succumbing to typical symptoms of self-aggrandizement and paranoia. E. A. Mahama’s work appealed to Acheampong, who sought national food security, and the two men had a cordial rapport, until Mahama senior committed a mistake: he wrote a letter to the general “to offer him a bit of the insight he’d gleaned from his years as a politician.” He advised Acheampong to quit while he was ahead—“to leave when the applause is loudest,” and to secure his legacy by lifting the ban on political parties and beginning the transition to civilian rule. The advice was not well received: Mahama senior was brought in for questioning, and later, when somewhat obliquely described events saw him lose control of his company to other shareholders, the general was of no recourse. In 1980 the father re-entered politics under the short-lived and ineffectual Limann civilian government; after Flt. Lt. Jerry Rawlings staged his second coup, on December 31, 1981, another round-up and bloody purge beckoned, and this time, E. A. Mahama fled the country, escaping to Côte d’Ivoire in a fraught journey that the son describes vividly, and later moving on to Nigeria.

By that point, John Dramani Mahama had earned his history degree (his third choice of subject, but one he came to enjoy) from the University of Ghana, and returned to Tamale to fulfill two years of national service by teaching at the secondary school from which he’d graduated. His status as a teacher earned him a modicum of respect, but soldiers were roaming about, and the atmosphere was unpleasant. The economic situation was catastrophic and an immense brain drain was on. Mahama joined his father in Nigeria: “Leaving Ghana wasn’t as difficult as I imagined. The country had hit rock bottom.”

Nigeria offered only temporary shelter. The wealth contrast was striking—“Nigeria was beaming with prosperity and promise”—there was construction everywhere and the rich sprinkled money around ostentatiously. But social relations were poor. Religious and ethnic communities clashed violently in the north. More ominously, anti-Ghanaian prejudice was brewing unchecked. One day, Mahama watched a vigilante mob murder a Ghanaian alleged thief, first beating him to a pulp then hoisting a tire over his neck, dousing it in petrol and setting it alight. Mahama was powerless: “If I so much as spoke a word, they would be able to tell that I was a Ghanaian, too. … I’d never witnessed someone being murdered before. It was devastating.” By the time Nigeria enacted its mass expulsion of Ghanaians in 1983, Mahama and his father had left; the father, for London, the son, back home.

“Writing became my salvation,” Mahama says of that time. It was both coping mechanism and useful tool: “I wanted to become a better communicator.” He found his way to a post-graduate program in communication studies at the national university, and later, to a two-year social science fellowship in Moscow while the Soviet Union was in the throes of perestroika. That experience put Mahama, who had become enamored with socialism in secondary school, in the midst of the ideology’s self-questioning and crisis. It made him feel better about Ghana, where things were improving on both economic and political fronts. To expect Ghana or any other newly independent country to find all the answers in a few short years, he realized, “was to deny it the right to grow and learn on its own terms.” How this revelation would lead Mahama into politics is left unsaid: this memoir ends in the mid-nineties, and Mahama characterizes that period, when Rawlings remained president but as a civilian, in only cursory terms, and doesn’t touch on the last 15 years at all. With Mahama now president and running for election in his own right this December, representing a National Democratic Congress (NDC) in which Rawlings and his wife, Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings, command a strong faction, the editorial decision seems, in hindsight, most politic.

“Writing became my salvation,” Mahama says of that time. It was both coping mechanism and useful tool: “I wanted to become a better communicator.” He found his way to a post-graduate program in communication studies at the national university, and later, to a two-year social science fellowship in Moscow while the Soviet Union was in the throes of perestroika. That experience put Mahama, who had become enamored with socialism in secondary school, in the midst of the ideology’s self-questioning and crisis. It made him feel better about Ghana, where things were improving on both economic and political fronts. To expect Ghana or any other newly independent country to find all the answers in a few short years, he realized, “was to deny it the right to grow and learn on its own terms.” How this revelation would lead Mahama into politics is left unsaid: this memoir ends in the mid-nineties, and Mahama characterizes that period, when Rawlings remained president but as a civilian, in only cursory terms, and doesn’t touch on the last 15 years at all. With Mahama now president and running for election in his own right this December, representing a National Democratic Congress (NDC) in which Rawlings and his wife, Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings, command a strong faction, the editorial decision seems, in hindsight, most politic.

My First Coup d’Etat is at least as much a family memoir as a political one, though on this front too, one feels that quite a lot more could have been told. A number of set pieces feel forced: for instance, an extended section in which Mahama recalls standing up to a bully while a primary school pupil at the prestigious Achimota School, and compares the bully’s method of intimidation to those of the dictators who were sprouting across Africa at the same time. Various allusions to myth and folk tales fall a little flat. And the prose, while clear, open, and possessed of the ring of honesty (writer Meri Nana-Ama Danquah is warmly credited, in the acknowledgments, for her collaboration), takes few if any risks.

But the work has plenty of force, not only as a vibrant testimonial to the experiences and influences that mark the generation now ascending, across the continent, to the apex of politics and industry, but on its own narrative merits as well. One very strong theme—supported by material that is little short of haunting—is the arbitrariness of family and individual destinies, even identities, in the compressed experience of colonization and its aftermath. Mahama senior, we learn early in the book, owed his Western education (and ensuing status) to the whim of a colonial district commissioner, who had come to the grandfather’s compound to find a child to enroll in school. The elder Mahama was a small child with a protruding navel, which the commissioner felt moved to pinch. The child instinctively struck back, knocking off the commissioner’s hat, but also inscribing himself in the man’s mind as the boy to select for education. From this small act of colonial condescension and patronizing magnanimity, a family’s fortune was made.

Names, too, are arbitrary. The colonial system required patronyms, so Mahama, the father’s first name, became the family surname. Christian schools demanded Christian first names, so the father became Emmanuel, and eventually the author’s older siblings became Adam, Peter and Alfred, those being the choices offered by a school headmaster. These older brothers in turn selected “John” for their younger sibling Dramani. “Our father didn’t protest or disagree,” Mahama writes. “I think that’s because he knew that he would merely be delaying the inevitable.” Only much later, upon entering politics, would John Mahama bring his birth name, Dramani, back into his public appellation.

There was another son too: Samuel, who, in an eerie echo of their father’s experience, was taken to London in the late 1960s by a missionary couple who were returning there. Mahama waits until the book’s final chapters to introduce this topic, and it’s devastating. “The Thompsons told Dad that in order to take Samuel to London with them, they would have to be his legal guardians … Dad agreed to sign over his parental rights. To him it was nothing more than a formality.” The mother disagreed; like Mahama senior’s mother in her time, who “suffered an anguish that everyone believed eventually led to her death,” she too was devastated. “The hurt never went away,” Mahama writes; the marriage did not survive. The missionary couple supplied the family with updates but when Mahama senior visited England for work, they never let him see his son. When E. A. Mahama took refuge in London after leaving Nigeria in the 1980s, he became obsessed with finding Samuel; that search’s ending is related in the memoir’s coda. It’s not an unhappy dénouement, but it’s still bittersweet—a reminder that in countries still so new, those entrusted with the high goal of assembling and leading the nation do so against the background of so many private wounds and ruptures, usually untold.

Guinean-Swiss photographer Namsa Leuba “merging” aesthetic traditions

Namsa Leuba is a Guinean-Swiss photographer who is occupied with merging two aesthetic traditions in her artwork. Leuba’s photographs for NY Magazine’s recent (and annual) “Fashion Issue” (also featured on the magazine’s new fashion blog The Cut), are at one glance visually compelling. Bored with your average fashion spread, Leuba instead uses the shoot as a means to experiment with cultural iconicity, fine art photography, and of course, fashion. Parsing through her images for this series it isn’t hard to spot her wide array of visual tropes: layering textures, juxtaposing backgrounds, displacing the familiar, vibrant punches of color, cultural allusions etc. Perhaps just as interesting are her tag along texts. Here, between word and image, is our gateway in.

Namsa Leuba is a Guinean-Swiss photographer who is occupied with merging two aesthetic traditions in her artwork. Leuba’s photographs for NY Magazine’s recent (and annual) “Fashion Issue” (also featured on the magazine’s new fashion blog The Cut), are at one glance visually compelling. Bored with your average fashion spread, Leuba instead uses the shoot as a means to experiment with cultural iconicity, fine art photography, and of course, fashion. Parsing through her images for this series it isn’t hard to spot her wide array of visual tropes: layering textures, juxtaposing backgrounds, displacing the familiar, vibrant punches of color, cultural allusions etc. Perhaps just as interesting are her tag along texts. Here, between word and image, is our gateway in.

In her accompanying comments, Leuba discusses the emanating power and energy of her models’ strong poses and potent, symbolic accessories. She even begins to interchange the terms model, statuette, woman, and this fusion becomes visually evident in her work. In the best of these photos, the models co-opt the surreal backgrounds while retaining a quiet, collected power. This is quite the coup in contrast to many fashion shots, whereby power is achieved through flaunting sexuality, exaggerating poses, or securing action shots. Leuba, however, manages to circumvent these obvious plays, and this she does by mining Guinean culture, pulling out those aspects which draw from objets d’art and social bearing.

Indeed, much of her word choice evokes the otherworldliness she attempts to construct through her choice and hidden placement of material objects and accessories. Words such as “magical”, “enchanting universe”, “goddess”, “potions”, “spirits” draw from both the mythology, and religious and cultural practices found in many cultures, but most specifically, she draws from Guinea. These accessories she imbues with charged words, and charged properties hang from the bodies of her models. Most prevalent in the series is a wig, which invokes the power of hair: a force to keep away evil spirits, to increase beauty, display youth, etc. Hair has a long and widespread cultural history of power, Samson, Samurai, here, Guineans, and, of course, women, all come to mind. Other accessories included are cow horns, a shell, and bottles packed with protective potions.

We can see a direct link to this series of fashion photographs from her previous work Ya Kala Ben. In her artist statement for Ya Kala Ben Leuba writes, “In recontextualizing…sacred objects through the lens, I brought them in a framework meant for Western aesthetic choices and taste.” And this vision comes through strong in her series for The Cut. This desire to aestheticize the western experience of consuming fashion by infusing it with Guinean visual culture stripped of its significance. The surface beauty of her photographs is thus rendered thin, which is why her side commentary is so important; it adds the meaty, missing layers that her “recontextualizing” stripped. Yes, her photographs can stand alone. But if so they stand alone in fashion not fine art.

Leuba’s work is important because first, it helps us understand what the normative is, and second it tests the soft spots in the “western framework” and profits from its (and the audience’s) malleability to accommodate the work. We are increasingly headed into a remix culture, one that is constantly adding to our understanding of old and new, foreign and domestic, in ways that enrich us all in our approach to navigating the chimeric visual landscape. Leuba is well in keeping up.

Namsa Leuba: African Accessories to the Western Aesthetic

Namsa Leuba is a Guinean-Swiss photographer who is occupied with merging two aesthetic traditions in her artwork. Leuba’s photographs for NY Magazine’s recent (and annual) “Fashion Issue” (also featured on the magazine’s new fashion blog The Cut), are at one glance visually compelling. Bored with your average fashion spread, Leuba instead uses the shoot as a means to experiment with cultural iconicity, fine art photography, and of course, fashion. Parsing through her images for this series it isn’t hard to spot her wide array of visual tropes: layering textures, juxtaposing backgrounds, displacing the familiar, vibrant punches of color, cultural allusions etc. Perhaps just as interesting are her tag along texts. Here, between word and image, is our gateway in.

Namsa Leuba is a Guinean-Swiss photographer who is occupied with merging two aesthetic traditions in her artwork. Leuba’s photographs for NY Magazine’s recent (and annual) “Fashion Issue” (also featured on the magazine’s new fashion blog The Cut), are at one glance visually compelling. Bored with your average fashion spread, Leuba instead uses the shoot as a means to experiment with cultural iconicity, fine art photography, and of course, fashion. Parsing through her images for this series it isn’t hard to spot her wide array of visual tropes: layering textures, juxtaposing backgrounds, displacing the familiar, vibrant punches of color, cultural allusions etc. Perhaps just as interesting are her tag along texts. Here, between word and image, is our gateway in.

In her accompanying comments, Leuba discusses the emanating power and energy of her models’ strong poses and potent, symbolic accessories. She even begins to interchange the terms model, statuette, woman, and this fusion becomes visually evident in her work. In the best of these photos, the models co-opt the surreal backgrounds while retaining a quiet, collected power. This is quite the coup in contrast to many fashion shots, whereby power is achieved through flaunting sexuality, exaggerating poses, or securing action shots. Leuba, however, manages to circumvent these obvious plays, and this she does by mining Guinean culture, pulling out those aspects which draw from objets d’art and social bearing.

Indeed, much of her word choice evokes the otherworldliness she attempts to construct through her choice and hidden placement of material objects and accessories. Words such as “magical”, “enchanting universe”, “goddess”, “potions”, “spirits” draw from both the mythology, and religious and cultural practices found in many cultures, but most specifically, she draws from Guinea. These accessories she imbues with charged words, and charged properties hang from the bodies of her models. Most prevalent in the series is a wig, which invokes the power of hair: a force to keep away evil spirits, to increase beauty, display youth, etc. Hair has a long and widespread cultural history of power, Samson, Samurai, here, Guineans, and, of course, women, all come to mind. Other accessories included are cow horns, a shell, and bottles packed with protective potions.

We can see a direct link to this series of fashion photographs from her previous work Ya Kala Ben. In her artist statement for Ya Kala Ben Leuba writes, “In recontextualizing…sacred objects through the lens, I brought them in a framework meant for Western aesthetic choices and taste.” And this vision comes through strong in her series for The Cut. This desire to aestheticize the western experience of consuming fashion by infusing it with Guinean visual culture stripped of its significance. The surface beauty of her photographs is thus rendered thin, which is why her side commentary is so important; it adds the meaty, missing layers that her “recontextualizing” stripped. Yes, her photographs can stand alone. But if so they stand alone in fashion not fine art.

Leuba’s work is important because first, it helps us understand what the normative is, and second it tests the soft spots in the “western framework” and profits from its (and the audience’s) malleability to accommodate the work. We are increasingly headed into a remix culture, one that is constantly adding to our understanding of old and new, foreign and domestic, in ways that enrich us all in our approach to navigating the chimeric visual landscape. Leuba is well in keeping up.

September 18, 2012

Hugh Masekela’s ‘Stimela’ gets a makeover

R&B singer-songwriter Wynter Gordon is taking a considerable step outside her comfortable mid-commercial range with her new single ‘Stimela’ and its self-directed video, but it’s hard to argue that it isn’t reeking of the worst type of structural World Music arrogance. It practically has it all: the cleverly metaphorical words from Hugh Masekela’s lament of migrant workers reduced to exotic vocal effect. (Or are they? “Running, running…”) The full gamut of stereotypes of Africa – wilderness, tribalism, “wisdom and truth” and the ignorant generalization of having a tiger to represent Africa.

But something in the blinking, refracting shadows of the video and the Weeknd-inspired cross-linking swirl of wavering sound suggests more challenging possibilities: borders dissolving between human, animal and machine, and between certainties and stereotypes. “I’m a hostage in this skin,” she sings, yet somehow the music and images make escape from the power structures sound eminently possible.

* ‘Stimela’ is available as a free download on Wynter Gordon’s EP Human Condition: Doleo.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers