Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 520

September 30, 2012

My favorite photographs N°8: Sydelle Willow Smith

Among the most striking portraits in South African photographer and filmmaker Sydelle Willow Smith’s online portfolio are those taken in the Western Cape, reflecting much of what Cape Town and the wider province stand for: the engaging (solidarity and protest marches; parades; a reportage about Blikkiesdorp, no longer just a “temporary” village echoing the crudest forms of Apartheid-like urban planning), the entertaining (the music and party scenes), and the ugly (simmering xenophobic feelings against foreign migrants). When asked to pick and comment on her five favorite photographs, she sent through the following.

Among the most striking portraits in South African photographer and filmmaker Sydelle Willow Smith’s online portfolio are those taken in the Western Cape, reflecting much of what Cape Town and the wider province stand for: the engaging (solidarity and protest marches; parades; a reportage about Blikkiesdorp, no longer just a “temporary” village echoing the crudest forms of Apartheid-like urban planning), the entertaining (the music and party scenes), and the ugly (simmering xenophobic feelings against foreign migrants). When asked to pick and comment on her five favorite photographs, she sent through the following.

This first photo (above) was taken on the outskirts of Livingstone during Greenpop’s Trees for Zambia Project last July. I am always amazed at how keen people are to have their photograph taken, even if you tell them you probably won’t be able to get them back a copy. The kids began performing for the camera at their school and we took a couple of fun shots of myself and them; in a moment they relaxed and I snapped, and got the “real” moment I was hoping for — whatever that means.

Earlier this year I was given a press pass to photograph the J&B Met, a high-end horse racing event in Cape Town. I wondered around in the hot sun thinking of Martin Parr’s work. At the end of the day, sunburnt and annoyed with the lavish nature of the event I left. At the entrance a group of promoters were eagerly harassing passers-by and I snapped this picture. I love the balance between the strength of the man and the delicateness of the woman:

In January 2010 I was lucky enough to travel to Diani Beach in Kenya to work on ‘Skiza’, a cultural exchange project. After that my partner and I decided to go and explore Lamu Island. Off the coast of Mombasa, teeming with Muslim Kenyans, a couple of tourists, and donkeys, this no car tourist haven was fascinating.

Fishermen still use ancient dhal fishing boats, the serenity was incredibly calming. When we left we learnt oil had been discovered off the coast. I am not sure what Lamu is like now.

I am working as an anthropology researcher/photographer on a book by The African Centre for Cities at the University of Cape Town. I met a woman, Thoka, selling chickens (“nkukus”) on Landsdowne Road and got to know some of her chickens soon to be sold for R15-20 a pop, township free-range style.

When I was studying photography at The Market Photo Workshop I used taxis to get from the North of Johannesburg where I grew up to town. Jozi taxis use a sign system. When I moved to Cape Town I was fascinated by the fact that taxis work in a team with a gaatjie who shouts out the route, counts the change (thank god as getting stuck in the front of a Jozi taxi and having to count change sucks). This gaatjie let me hang out with him for an afternoon on his Claremont route, he also explained that he used tik while he was working as the kick made him better at his job of herding potential customers to his taxi.

Visit Sydelle’s website and her facebook page to see more of her work.

September 29, 2012

Weekend Music Break

Got caught up in other stuff yesterday, so this week’s Bonus Music Break comes a day late. “Sister Deborah” Owusu-Bonsu calls herself a “creative hustler” and yes, she is the sister of FOKN Bois’s Wanlov the Kubolor, which helps explain the video above.

Yahkeem from Motherwell, Port Elizabeth (also known as the Nelson Mandela Metropole) in South Africa’s Eastern Cape:

E.L.’s “infusion of Japanese and Chinese culture with Ghanaian Azonto music” (H/T 25toLyf):

Serge Beynaud, working those Abidjan-Paris connections:

New Sexion d’Assaut. ‘Ballader’ (“taking a stroll on the Champs-Elysées”):

I’ve been listening to Staf Benda Bilili’s album ‘Bouger Le Monde’ a lot lately. It’s excellent:

From the archives (1974), taken from the “Soul Power” documentary, Miriam Makeba performs ‘Qongqothwane’:

Makeba introducing the song in French reminded me of a question I’ve asked elsewhere but to no success so far: between 1985 and 1990, and in between touring with Paul Simon, she lived in Brussels (in the Woluwe-Saint-Lambert area). I’ve never found the house she lived in. Anyone knows where exactly she stayed?

Now and then I browse the web looking out for work by the elusive cinematographer Kahlil Joseph. This video he did for Flying Lotus recently is sublime:

Lee Fields’s retro soul style (I’m a fan, of his live shows especially):

And Alabama Shakes got a new studio video out too:

September 28, 2012

Antjie Krog and the ‘magical power of literature’

South African poet and writer Antjie Krog recently gave a talk at the Open Book Festival in Cape Town, republished in The (UK) Guardian this week. Krog spoke alongside Njabulo Ndebele, who is seminal to discussions on South African literature not only because of his call to include, in new South African narratives, the lives of women who quietly soldiered on, but also because of his beautifully crafted criticism reflecting on the need for his fellow writers to turn towards ‘ordinary’ subjects, after traumatic years of writing about the extraordinarily violent lives they led under apartheid. His piece was not published by The Guardian. (You can read it here.)

South African poet and writer Antjie Krog recently gave a talk at the Open Book Festival in Cape Town, republished in The (UK) Guardian this week. Krog spoke alongside Njabulo Ndebele, who is seminal to discussions on South African literature not only because of his call to include, in new South African narratives, the lives of women who quietly soldiered on, but also because of his beautifully crafted criticism reflecting on the need for his fellow writers to turn towards ‘ordinary’ subjects, after traumatic years of writing about the extraordinarily violent lives they led under apartheid. His piece was not published by The Guardian. (You can read it here.)

We are unsure about the politics of inclusion and exclusion here; perhaps it was just a case where one writer agreed to publish in one newspaper, and the other in another. However, having both writer-critics’ talks published together would surely permit readers to think in clearer and broader critical terms about what’s at stake for literature, especially during shaky political periods.

Basically, in her talk, Krog is saying that the political has always been intertwined with the poetic in South Africa. Afrikaner and African alike, South Africans made poetic language the vehicle through which they expressed their desires for inclusion into/what it meant to experience rejection from the centres of power’s embrace. In this essay, she is able to poetically (and magically) evoke such disparate threads and braid vastly different leaders (Verwoerd and Mbeki among others) into a rope that does not — though it seems she should — hang them.

Krog is able to revisit the reviled Verwoerd with complicated adoration (although I have a hard time agreeing with her argument here — that Verwoerd did not censor the playwright NP van Wyk Louw, but ‘engaged’ him by trashing his play’s tentative questioning of nation-formation and nationalism in front of “three quarters of a million people” assembled at the Voortrekker monument). So heavy was the power Verwoerd wielded that the poet was wounded beyond the flesh. Did van Wyk Louw recover? Could the public re-embrace him after such a masterful censure (though he was not directly censored)?

These spots where I find Krog romanticising with fly whisk and magic water are the most troubling in her essay.

I’m troubled by the tendency to regard literature as a ‘solution’ in times of political trouble. As if it will magic potion away the ignorant actions of the powerful people who often control our destinies. People who are well read are often immune to others’ suffering and conversely, one may easily find illiterate people who are compassionate.

Her claim that “literature inflects the anguish of reality in a way that theoretical discussions of the same issues cannot achieve, making possible a kind of understanding not accessible by other means” also has ritualistic overtones, with ‘story’, ‘narrative’ and perhaps also ‘author’ and ‘book’ as material objects aiding transfiguration.

As I read her essay, I am waking up to an ancient Buddhist tradition in Sri Lanka: monks chanting ‘pirith’: sutra and incantations to form a pearl necklace of protection around the sangha (followers) and the island. My parents’ families and ancestral homes are within earshot of Kelaniya Vihara, a renowned temple here. Waking up at 5 am to hear that rhythmic incantation through the chants of tree frogs, night birds, and still-sweeping fruit bats means I cannot dismiss the mythical ability of poetic language to alert, direct, and yes, transform the subject.

It is enchanting, quite literally.

Krog is alluding to that ability of narrative to involve the emotional, and invoke the intellectual and spiritual, to have staying power in a way that journalistic reportage cannot (today’s headline is tomorrows chip roll wrap).

It is an old theme, explored as far back as 1579, by Sir Phillip Sydney in ‘The defense of Poesy’.

I can let that cliché go, given all the homeland magic I’m experiencing at dawn. And I always remember that reading Krog’s work, I learnt a lot about what it means to be part of a tradition-bound, privileged group who reinforced their powerful positions by misusing religious texts, erroneous history, military might, political rhetoric, and yes, breathtakingly beautiful poetry about our right to a magical location.

However, I must take issue with Krog’s focus on literature and its relationship to what she calls ‘anguish’. I know that it is trauma that she has special aptitude for writing. It’s true that Krog’s ability with language can make the vilest moment of human debasement sing an aria: not in glory of that deed, but in/as an offering. It is as if she writes, “this, too, Lord, is we whom you created” — the horrors through which one can still witness the divine are an essential portion of such transfigurations. In doing that, Krog is in Goya territory, meditating on suffering in order to get to ecstasy.

So I return to that anguish: suffering may help us understand that transfiguration is necessary, inevitable, unavoidable. But small daily beauties and simple meditations also have that same capacity.

In the interdisciplinary courses I teach, literature, art and photography play an essential part of that transformative process. But it only really happens together with the intellectual, theoretical,and historical. The students I see truly moved are not made so mobile by the poetic and emotional alone, but are more apt to be so if their reading is accompanied by foundational knowledge that provides them with tools to analyse, stand aside, jump into the foray, and critique as they absorb story.

Surely, Krog can’t be naive enough to say that if Mbeki or Zuma et al read x, y, or z, they would understand their subjects’ anguish, and make better policies. After all, much of what she had to read as a child was meant to mould her not into a rebel but a ‘righteous’ woman, who in turn produced similarly moulded children. Verwoerd, upon seeing van Wyk Louw’s play, used his might and platform to effectively demean tentativeness or querulousness in the face of grand glory and nation-building. He wasn’t aiming to encourage the dissident heart, let alone outright dissent.

Our monks’ chanting is now over. Part of listening to this rhythm in the morning, before the honking of buses and rumble of lorries, is in the meditative dream state that rhythmic incantation brings about — like listening to a quiet choir. But the reflection on the meaning of the Pali words engages a different set of processes. You don’t have to know Pali or know the contexts in which these verses were produced — in fact, most Sri Lankan Buddhists do not. In order to experience ‘ecstasy’, one does not have to go through the rigours of ecclesiastical discipline in order to feel that unexpected and often undeserved moment where the sacred enters one’s ordinary life. But knowledge of Buddhism’s teachings, arrived at through a combination of the historical, political, theoretical and spiritual, changes so much of about how I experience my small transformation at dawn each day here.

September 27, 2012

The musical journey of Bongeziwe Mabandla

Forty-two kilometres from Umthatha, the former capital of Transkei in the Eastern Cape, South Africa, is kuTsolo. It’s a small town with a name which means pointed, referring to the shape of the hills characterising the rural landscape. It is far from the scintillating big city lights, and it is home to the young and undeniably talented musician Bongeziwe Mabandla. As is often the case with many a budding artist in South Africa, Bongeziwe now lives in Melville — the decidedly cool and creative suburb of Johannesburg — where he is currently mixing and blending his music. With his distinct voice, Bongeziwe has begun to pique the interest of many in South Africa, and beyond. There is a certain quality in his voice, which lends itself to the exploration of raw emotion.

“I felt like there was a lot of pain beneath a song; that even an optimistic song has an underlying sadness,” Bongeziwe says, while describing the title track of his recently released album Umlilo. The name means “fire” in isiXhosa, but aside from its direct meaning, it is also a word play on isililo, meaning a cry. “I wrote the song ‘Umlilo’ and realised that this was the central theme. Tears, crying, pain and anger turned into something powerful; Fire!”

Umlilo has a deep melancholic tone and is a fusion of various elements, mixing ingredients from maskandi, dub, rock and traditional folk music tempered with a blues sensibility. Dr. Cornel West defines blues as ‘personal catastrophe lyrically expressed’. An apt description for Bongeziwe who is no stranger to pain. However, he has found a way, through the process of a kind of alchemy, to transform that pain and anger into something sublime, something powerful.

“I sometimes take a moment to think whether people really know where my songs come from,” he says. “I always have to remember why I wrote a song so I can perform it with the correct feeling.”

There is a strong storytelling element in his music, spinning tales of freedom, poverty, struggle, anger and love, all in the context of South Africa.

“I write about things that impact me a lot, I always want my music to relate to people’s lives so a lot of the lyrics are about what I go through. I am inspired by the pain, the joy, the anger, the passion but mostly the sadness.”

Bongeziwe’s list of influences is long, the most prominent being Lauryn Hill along with Tracy Chapman, Busi Mhlongo, Jabu Khanyile, Ayo and Simphiwe Dana.

In high school Bongeziwe taught himself to play the guitar from YouTube videos. It was merely for the fun of it then. During this time he also discovered that he enjoys song writing and could see himself recording. His musical journey took a more serious turn when he started playing with a group called The Fridge and this, he says, helped him shape his sound and gain the experience of playing with a band. What had started as a hobby began to turn into something more.

“The first song I worked on was ‘Isizathu’. At that time I wanted to write something clean and clear! I wanted to prove myself and I was very nervous, but ‘Isizathu’ is one of the singles in my album now!”

A few years ago Bongeziwe met producer Paulo Chibanga of the group 340ml and they started putting together some songs. Umlilo is a product of their cooperation. In June this year Bongeziwe signed a deal with a major label, Sony Music Africa. Now, a few months later the ink has dried and a few illusions have been shattered.

“I thought that it would mean I would not have to worry about anything again,” he laughingly admits and adds, “it’s really funny how one always wants to get the deal not thinking about the struggles within the deal — I thought that things would change overnight, but I have to work harder now. I have so much to do and need to do it right.”

The latest single ‘Gunuza’ is a social commentary on the behaviour and goings-on of the rich and powerful people in a country with a brutal history of oppression.

“That song was written around election time here in South Africa,” Bongeziwe stresses. “As a person I felt ignored in my society. I felt that people that mattered were people with money! So I wrote about the character Mr Gunuza. I wanted to show people that we are driven by money and that we only respect people who have it. I wanted to ask the question! What if we went deeper into a rich man and asked ourselves who is he? Would we still applaud or would we be disappointed?”

The video for ‘Gunuza’ is shot in a rural setting reminiscent of his humble beginnings in kuTsolo. It depicts an environment of relative poverty which he is familiar with, having been raised by a single mother in the village of Somavili.

“I never thought that where I grew up was important, but now I understand the beauty of growing up in rural Transkei. I am aware of the value of the lifestyle in rural areas — how we didn’t know what it was to be disrespected or devalued just because we were poor or black. I wanted to place people in an environment, like back home, and also just to tell the story as I saw it happen.”

Bongeziwe speaks very fondly of his mother saying she taught him the importance of pursuing his dreams. The song ‘Ngawe Mama’ is dedicated to her.

Bongeziwe shows obvious concern about the album sales. So far, the media and audience response have been positive, although the excitement generated hasn’t yet fully translated to sales. The process seems to be taking some time. This however hasn’t detracted him from his resolve to continue to work on his craft. He is determined to keep making the kind of music that means something to him. He’s already making plans for the next project. Perhaps the music sales will gain momentum as Umlilo spreads from place to place around South Africa, or perhaps it will create a cult following; one that does not subscribe to any particular geographical or linguistic borders. After all, it is not unheard of for African musicians with a distinct style, to receive a warm welcome internationally, while struggling to get a response from the home audiences.

As the revenue streams of the music industries are changing, the album sales are becoming less central. While money can be made out of hit singles, for a career in music one stands a better chance with powerful live performances and touring. For that there needs to be a connection between the audience and the artist. The audience has to feel the art and if there is one thing above everything else to be said about Bongeziwe Mabandla, it is that his sound will make you feel.

* Amkelwa Mbekeni is one half of the Planet Earth Planet Rap International Hip-Hop segment of And You Don’t Stop! radio show on WBAI (New York).

September 26, 2012

10 African films to watch out for, N°4

Here are another 10 films we’re hoping to see in the (near) future. First, three “fiction” films. ‘Winter of Discontent’, a film by director Ibrahim El Batout is set against the backdrop of the 2011 Tahrir Square protests, zooming in on the the lives of activist Amr (Amr Waked), journalist Farah (Farah Youssef) and state security officer Adel (Salah Alhanafy):

‘Kedach Ethabni’ (“How Big Is Your Love”) is a film by Algerian director Fatma Zohra Zamoum probing “tradition and modernity” through the lives of a three-generation family in Algiers. An English-subtitled trailer here and an interview with the director here.

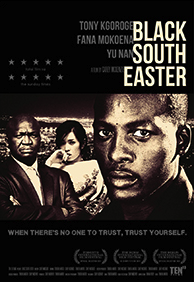

‘Black South-Easter’ by director Carey McKenzie, starring Tony Kgoroge, is set in Cape Town and tells a story of police corruption. I’m told it has a very good soundtrack too. No trailer yet.

‘Black South-Easter’ by director Carey McKenzie, starring Tony Kgoroge, is set in Cape Town and tells a story of police corruption. I’m told it has a very good soundtrack too. No trailer yet.

And seven documentaries:

‘Babylon’ is a film by Ismaël Chebbi, Youssef Chebbi and Ala Eddine Slim. In the aftermath of its own revolution, Tunisia received an influx of displaced persons from Libya, who got housed in camps. The film traces, without any voice-over commentary, the construction and closure of one such camp. A fragment:

(Three more fragments here.)

‘Noire ici, Blanche là-bas’ (“Black here, White there”) is an addition to the growing diasporic body of recent and very personal films about the searching for one’s roots. Born in Congo to a French father and a Congolese mother, and having moved to France at a young age, Claude Haffner films her own ongoing quest, returning to and visiting relatives in Mbuji-Mayi. No English trailer yet:

Philippa Ndisi-Herrmann is working on a documentary about the development of “Africa’s largest port” on the island of Lamu, off the Kenyan coast. We Want Development (but at what cost?)

In ‘Our Bright Stars’, a film directed by Sidi Moctar Khaba and Frédérique Cifuentes, various people from South Sudan share their expectations of the new nation:

François Ducat and Frank Dalmat have made a documentary about Zimbabwean music band Mokoomba (‘d’une rive à l’autre’; “from one [river] bank to the other”):

(Here’s another fragment.)

In ‘One Day in the Madrassa’, filmmaker Youssef Ait Mansour goes on a journey to meet his brother who has chosen to live in a secluded madrassa in the Moroccan desert:

And, also set in Morocco, ‘Bahr Nnass’ (“Sea of Tears”) by director Marouan Bahar is a critical film that follows a seaweed-digging diver as she struggles to make ends meet for her family:

* Our previous new films round-ups: part 1, part 2 and part 3.

The art cliché about ‘struggle photography’

The American historian and curator Jon Soske has written how it is now an art cliché that during the final decade of Apartheid, South African photographers embraced a social documentary mode that subordinated the image to the propagandistic needs of the moment.

The American historian and curator Jon Soske has written how it is now an art cliché that during the final decade of Apartheid, South African photographers embraced a social documentary mode that subordinated the image to the propagandistic needs of the moment.

The cliché further goes that these photographers embraced “naïve literalism over aesthetic experimentation,” and “reduced the complexities of interior experience” to “the mute fact of African suffering.” Documentary photographers were said to have become content merely “to record spectacular instances of repression or deprivation.” The result: They codified a one-dimensional and thus dehumanizing image of black life; “political reportage straight-jacketed the artist. Realism trumped self-reflection … High politics eclipsed the importance of everyday life.”

One of the groups usually included, unfairly, in this cliché is the 1980s photography collective and photo agency, Afrapix. Launched in 1982 by a group of black and white photographers and political activists, the group played a “seminal role” in the development of “a socially informed school of documentary photography in Apartheid South Africa.” Basically, a second wave of social documentary photography in South Africa. In effect, updating David Goldblatt and Ernest Cole for late Apartheid.

In their own words Afrapix “stretched the boundary between the requirements of hard news and developed a socially relevant documentary photography practice that raised critical issues around the role of the photographer (as a witness to the times) and the complex relationship of how people in a racially fractured society were portrayed.”

Because they photographed community- and mass-based struggles and most of them openly themselves allied with anti-apartheid movements, their photography became known by the generic “struggle photography” description that would be later used as a slur against these photographers well after the group’s disbandment in 1991.

But that was also a caricature of Afrapix. In fact, Afrapix promoted a much broader range of photographic idioms, reflected complex emotions of his black subjects, their humanity, dignity, and the everyday realities of these black communities in often very personal terms “without abstracting their sorrows and joys from the overarching political context of Apartheid.”

One of the key members of that collective was Cedric Nunn, the subject of this retrospective exhibition and described by curator Okwui Enwezor as “one of the most important photographers of South Africa to emerge in the 1980s.” Born into a rural part of what is now South Africa’s Kwazulu-Natal province, into a large, significant mixed-race family with deep roots in the region (his paternal ancestors are English settlers and his maternal ancestors Zulu and Khoi), Cedric’s work incorporates a range of familiar themes (both overt and subtle)—structural racism, class politics, the legacies of Apartheid and the chimera of new South African black empowerment; of people on the margins, farm workers, homeless people and landless people. At the same time, Cedric’s work is also very personal. (Much of the work exhibited here comes from “Blood Relatives” that he started as a young photographer and also put the cliché outlined above, to a lie). It is also about his identity as a coloured South African.

What is interesting about Cedric is that he kept at these themes well after legal Apartheid ended, without necessarily implying a division between these two focuses—the struggle and the personal. Throughout the time he was photographing for Afrapix, he would return periodically to rural Kwazulu-Natal, where he photographed the world of his childhood, his extended family, and especially that of his grandmother, Amy Madhlawu Louw (in the photo above), who worked her own land until she was 88 and died when she was 103 in 2003. Amy Louw’s house—destroyed by land invaders when she died—now only exists in Cedric’s photographs. His work also includes photos of his mother who died in 2010.

As a long-time fan of Cedric’s work, I was delighted to be asked to say a few words at the opening of this retrospective. And it’s been wonderful hanging out with him and talking to him about the subjects of his photographs, his personal history, his approach to photography and his improbable personal journey.

Somewhere else Cedric has described his childhood as “very image scarce.” Cedric was expelled from high school at the age of fifteen, and was working in a sugar factory soon after he turned sixteen. He spent the next eight years working in that factory, and the experience was a transformative one in which he was swept up in the upsurge of worker organization and politics of the mid- to late seventies. In his own words, he had found himself a factory worker by default and sought to change that. Given his lack of education and the job discrimination of the day, this wasn’t easy. It was his father, Herbert Nunn, a shopkeeper, who told him when he was frustrated with his life, “Do something about it.” Cedric found photography when he saw the portfolio of a photography student at a technical college in Durban, Peter McKenzie (also later a member of Afrapix). He recognized the medium as one he could attempt and master.

With McKenzie’s help he set out to learn and soon found a mentor in Omar Badsha, probably the most prominent photographer of the Afrapix collective. Cedric also recalls with hindsight that he’d been exposed to the best of the Magnum photographers through the Time Life that his father subscribed to. Other influences on his work include other Afrapix members: Paul Weinberg, Santu Mofokeng (whose work is being exhibited in the same building) and Guy Tillim. Through Afrapix he was also influenced by David Goldblatt.

In Cedric’s works you’ll note a mix of the familiar sites of anti-apartheid struggle, of the news events of that time, that we can identify easily if you know that history, but it also includes work that is not as headline grabbing, which one critic has described as “more quotidian, and considerably quieter.”

I want to conclude with a quote from an interview I did last year with Cedric for a South African academic journal, Social Dynamics, where I asked him about his approach to photography. He said:

I have never felt comfortable with the category of ‘documentary photography’ and half seriously say that I’m not ‘a photographer’s photographer’. I see photography as one of the most democratic mediums of the contemporary world, much as writing is, in that since the advent of Kodak and the Brownie camera, photography has been a potential medium of the masses. Quite untrained, I was able, with a little direction, to use the medium to express my view of the country and world I inhabited. So, I wasn’t really trying to document neglected aspects of my society, as bringing witness to a view that was neglected by the mainstream media of the time. Naively, I thought I could record images of my familiar world, as well as the attempts to change the socially engineered world of the time, and this intuitive attempt was largely proved correct with time.

Let me close with something else Cedric has said about his work. In an interview with Okwui Enwezor, published in the book “Call and Response” that accompanies this exhibition, Cedric is asked to reflect on his work, and he responds:

I was a bit disappointed by the fact that I didn’t have that strength of conviction to follow my original vision. I would have produced far stronger work if I had followed that vision — those quiet images that I could have made if I had spent far more time exploring the backwaters and backstreets of the world that I lived in. If I had stayed with that, those are the images that I would have made…

* I made these remarks on September 12 at the opening of the exhibition “Cedric Nunn: Call and Response” at David Krut Projects in New York City. Here is a link to some images taken by the Gallery at the opening.

September 25, 2012

Torture in Zimbabwe

Last Thursday, Zimbabwe’s Supreme Court unanimously “chastised” state security agents for torturing Jestina Mukoko, national director of the Zimbabwe Peace Project, four years ago.

Last Thursday, Zimbabwe’s Supreme Court unanimously “chastised” state security agents for torturing Jestina Mukoko, national director of the Zimbabwe Peace Project, four years ago.

They came at dawn, December 3, 2008. Armed men broke into the house of Jestina Mukoko, the only surviving parent of a teenage child who watched, helplessly. They took her, in unmarked cars, and held her incommunicado for 21 days. During that time, they beat her feet with rubber truncheons. They dumped her into solitary confinement. They forced her to kneel on gravel, to endure searing pain. They questioned her about the whereabouts of her son. As Mukoko explains, “Psychological torture was the order of the day.” Under duress, the abductors, which is to say the State, handed Jestina Mukoko over to … the State. Where she was again imprisoned, in the notorious Chikurubi Maximum Detention Centre, after having spent time in police cells that had already been deemed “unfit for human habitation.”

Mukoko told this story in May to the Oslo Freedom Forum in a panel titled “Spotlight on Repression: A glimpse into some of the world’s least known and most repressive regimes.” Her talk is entitled “In Mugabe’s Crosshairs.”

Where does that torture begin? As Mukoko notes, at the outset of her talk, she was denied her freedom for 89 days in prison, but she has been denied her freedom for far longer than that.

Where does the torture begin? At the house invasion? The abduction? The disappearance? The beatings? The kneeling on gravel? The nights with drunken captors taunting and threatening her? The police cell? The prison? The mandated weekly visits to the police, while awaiting trial?

It also begins in the globally constructed status of “least known”. Four years ago, when Jestina Mukoko was abducted, and then for the three months of her ordeal, she was in the news. Zimbabwe was in the news. Then Mukoko was released, and her story was relegated to the conference halls of human rights organizations.

And so Zimbabwe, somehow magically, receded into the Brigadoon fog at the season’s end.

Except that Zimbabwe did not go away. Jestina Mukoko was not the only person abducted that year. Among the 20 or so abducted, at the same time, by ‘State security agents’, there was Nigel Mutemagawu, two years old. He was taken with his parents and held incommunicado. He was beaten and then left without medical attention. All of those cases are still pending. That means, as Mukoko explains, that they must drag themselves, every Friday, to the police station to verify their whereabouts: “I know how traumatic that is.”

Jestina Mukoko and so many others are still kicking in Zimbabwe. She’s suing the government for torture. She continues to document violations and to give voice to those who suffer atrocity. She, and many others, continue to work for the project that is peace. Where does the torture end?

September 24, 2012

Kehinde Wiley goes to Israel

Kehinde Wiley has seemed unstoppable. In the last five years, the artist has gathered praise from all over the place, established a high price for this work, and developed a highly distinctive style. His wildly ambitious World Stage series, documenting life in Africa, Asia, South America and the Middle East, looks for an unparalleled authority to represent the African diaspora. A recent trip to Israel, however, and the new sub-set he produced there — World Stage: Israel — raises some doubts about his practice.

The paintings were exhibited at the Jewish Museum in New York earlier this year (and can be seen on the artist’s website). The portraits are broadly consistent with Wiley’s previous work: a diverse group of men Wiley met during his trip, posed but realistically represented, overlaid with patterns from fabrics Wiley finds in a market.

There’s a video of Wiley’s trip, in which he meets a group of young Ethiopian-Israeli men, one of whom — Kalkidan Mashasha — raps about his journey from Africa to Israel:

Another version of the video, by Dwayne Rodgers, is available here. We see Wiley interviewing the rapper, who says:

Inside of me with hip hop I got no fear … when I got the hip hop you know I’m fearless … I feel like a got a weapon.

There are images of Wiley and his crew directing the sitters’ poses, and we hear the artist’s explanation for the World Stage series:

Each location I choose in the World Stage comes about because I want to mine where the world is right now, and chart the presence of black and brown people throughout the world … Every time I travel throughout the world I find there is a certain essence to black American culture that has been globalised, and there’s a sense in which every country finds its own specific response.

None of this is particularly objectionable; indeed it all feels a natural extension of Wiley’s artistic project up until now. The artist talks about how his expectations travelling to Israel were overturned, but it is not clear what they were replaced by. In spite of Wiley’s stated desire to ‘mine where the world is’, there does not seem to be any deep-thinking involved in his taxonomy, for which the social is mere ornamentation. Perhaps this is why his rationale for the Israel series seems superficial, almost naive.

After recent debates over the treatment of black and African citizens in Israel, including the complex exclusions of national identification Olufemi Terry wrote about on this blog, it is clear that this is an issue worthy of confrontation, and a contribution by an artist of Wiley’s stature should enrich the conversation. In a valuable review of the Jewish Museum exhibition at the Jewish Daily Forward, Jillian Steinhauer notes that it first appeared at Wiley’s gallery in LA, Roberts & Tilton, before coming to the east coast, and remarks “there’s still something disconcerting about vines of the commercial art world creeping into museum galleries like this.”

There’s no doubt that Wiley’s practice is determinedly founded in the commercial, almost Catholic interest in contemporary iconography: the details on a man’s t-shirt, his piercings, the numerous subtle ways cosmopolitans signal our distinction. In these paintings the tentacles of the decorative overlay are woven over and into the subjects, as if the painting were flirting with the idea of dispensing with its subject altogether, and filling the canvas with ornamentation.

Steinhauer’s conclusion is sharp, and possibly unimprovable:

Wiley has created small sculptures of two lions holding the Ten Commandments to top the frames of the Jews; the Arabs, meanwhile, get two lions holding a plaque with a Hebrew translation of the famous Rodney King line, “Can we all get along?” This vexes; its significance beyond vague feelings of brotherly solidarity is elusive. A more logical and potentially meaningful choice might have been a line from the Quran or from Arabic poetry — or at least the Rodney King line in Arabic. As an artist concerned with power and empowerment, Wiley could do better.

It’s unclear exactly what an art which confronts the complex political realities and powerful injustices of life in Israel would look like. The quotation from Rodney King’s appeal to racial unity is the most obvious evidence of Wiley’s failure to confront the demands of the task he set himself. A tragic footnote to twentieth century American history, King — the construction worker whose famous beating by a vicious gang of police was one of the catalysts of the 1991 LA riots, later won a large compensation settlement, struggled to overcome his alcoholism, appeared on several celebrity addiction TV programmes — was found by his fiancée at the bottom of a swimming pool in June, days before Wiley’s exhibition came down.

Kehinde Wiley’s practice

Kehinde Wiley has seemed unstoppable. In the last five years, the artist has gathered praise from all over the place, established a high price for this work, and developed a highly distinctive style. His wildly ambitious World Stage series, documenting life in Africa, Asia, South America and the Middle East, looks for an unparalleled authority to represent the African diaspora. A recent trip to Israel, however, and the new sub-set he produced there — World Stage: Israel — raises some doubts about his practice.

The paintings were exhibited at the Jewish Museum in New York earlier this year (and can be seen on the artist’s website). The portraits are broadly consistent with Wiley’s previous work: a diverse group of men Wiley met during his trip, posed but realistically represented, overlaid with patterns from fabrics Wiley finds in a market.

There’s a video of Wiley’s trip, in which he meets a group of young Ethiopian-Israeli men, one of whom — Kalkidan Mashasha — raps about his journey from Africa to Israel:

Another version of the video, by Dwayne Rodgers, is available here. We see Wiley interviewing the rapper, who says:

Inside of me with hip hop I got no fear … when I got the hip hop you know I’m fearless … I feel like a got a weapon.

There are images of Wiley and his crew directing the sitters’ poses, and we hear the artist’s explanation for the World Stage series:

Each location I choose in the World Stage comes about because I want to mine where the world is right now, and chart the presence of black and brown people throughout the world … Every time I travel throughout the world I find there is a certain essence to black American culture that has been globalised, and there’s a sense in which every country finds its own specific response.

None of this is particularly objectionable; indeed it all feels a natural extension of Wiley’s artistic project up until now. The artist talks about how his expectations travelling to Israel were overturned, but it is not clear what they were replaced by. In spite of Wiley’s stated desire to ‘mine where the world is’, there does not seem to be any deep-thinking involved in his taxonomy, for which the social is mere ornamentation. Perhaps this is why his rationale for the Israel series seems superficial, almost naive.

After recent debates over the treatment of black and African citizens in Israel, including the complex exclusions of national identification Olufemi Terry wrote about on this blog, it is clear that this is an issue worthy of confrontation, and a contribution by an artist of Wiley’s stature should enrich the conversation. In a valuable review of the Jewish Museum exhibition at the Jewish Daily Forward, Jillian Steinhauer notes that it first appeared at Wiley’s gallery in LA, Roberts & Tilton, before coming to the east coast, and remarks “there’s still something disconcerting about vines of the commercial art world creeping into museum galleries like this.”

There’s no doubt that Wiley’s practice is determinedly founded in the commercial, almost Catholic interest in contemporary iconography: the details on a man’s t-shirt, his piercings, the numerous subtle ways cosmopolitans signal our distinction. In these paintings the tentacles of the decorative overlay are woven over and into the subjects, as if the painting were flirting with the idea of dispensing with its subject altogether, and filling the canvas with ornamentation.

Steinhauer’s conclusion is sharp, and possibly unimprovable:

Wiley has created small sculptures of two lions holding the Ten Commandments to top the frames of the Jews; the Arabs, meanwhile, get two lions holding a plaque with a Hebrew translation of the famous Rodney King line, “Can we all get along?” This vexes; its significance beyond vague feelings of brotherly solidarity is elusive. A more logical and potentially meaningful choice might have been a line from the Quran or from Arabic poetry — or at least the Rodney King line in Arabic. As an artist concerned with power and empowerment, Wiley could do better.

It’s unclear exactly what an art which confronts the complex political realities and powerful injustices of life in Israel would look like. The quotation from Rodney King’s appeal to racial unity is the most obvious evidence of Wiley’s failure to confront the demands of the task he set himself. A tragic footnote to twentieth century American history, King — the construction worker whose famous beating by a vicious gang of police was one of the catalysts of the 1991 LA riots, later won a large compensation settlement, struggled to overcome his alcoholism, appeared on several celebrity addiction TV programmes — was found by his fiancée at the bottom of a swimming pool in June, days before Wiley’s exhibition came down.

Project Runway’s Southern belle vision of Africa

The 10th season of the American ‘Project Runway’ fashion show closed with its usual grand catwalk finale. Gunnar Deatherage, one of the budding candidates, said that for his collection he “was inspired by aborigines and exotic tribes”. There’s always one, isn’t there? But frankly, he doesn’t have the reference points to do ‘tribal’ even badly, especially when the tailoring is terrible and his understanding of how draping and fabric sit on a woman’s body is fundamentally in error (these are skinny women and they look all wide-hipped and chunky-waisted in the gathered skirts). The colour scheme is off. Do ‘tribals’ only wear earth tones mixed with dirty pink for some reason? Do paint splotched ‘aboriginal’ models always need to showcase a designer’s lacklustre tribal style over a soundtrack of loungy drums music?

Armani gives the same treatment to ‘Africa’ as does Michael Kors, with an over-abundance of dust on the colour scheme and plenty of geometric shapes on prints. But mostly, armani et al use solely white models, super-tanned with spray. The use of black models might give Deatherage some plus points, but when it’s used to reinforce a literally ugly stereotype, what’s the point? He may as well insert an Uncle Ben stirring rice and an Aunty Jemima serving breakfast, and have them saunter down the runway. This shouldn’t be the way beautiful black women get work — having to look like some Southern belle’s vision of Africa from yesteryear, one that said belles can visit for the fashion season, in order to get exoticism credentials.

One blogger’s advice to Deatherage: get yourself a passport and travel a bit first.

But I feel that might be exactly what he did: go on safari to Masaai Mara/Ngorongoro/(insert your fave), and cobble this thing together after taking some desperate notes back at the lodge, on the stylings of the ‘tribals’ hired to dance for visiting foreign bwanas.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers