Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 519

October 9, 2012

Interrupting Paris Fashion Week

I wasn’t given very much information. Stumbling into the secretive meeting I’d been invited to, an all female brigade greeted me quickly as they pored over a hand drawn map of targets. Drawing on an apparently endless supply of cigarettes, peppered sometimes with wine, they debated logistics. It being Paris Fashion Week, they decided Gucci, Dior, Jimmy Choo and Versace would be some of the hardest.

Some puttered about worried, complaining about the well-being of a group of mostly black women possibly being approached by aggressive French police officers. Others were too busy calculating the number of fences to be jumped in front of certain locales.

But at 3:25 am, armed with black scarves, homemade glue, brooms and emergency safety routes, they were ready.

The women hurried towards what they saw as an act of guerilla art-fare.

Volunteers hailing from Sierra Leone, Germany, Haiti, Morocco and Greece recently teamed up in Paris to participate in an extension of the French photographer JR’s ‘Inside Out Project’. Titled “Burning Borders and Building Bridges,” blown-up photographs of young men from the Folorunsho Collective in Freetown, Sierra Leone were plastered across the luxury retailers of the Parisian Avenue Montaigne.

Folorunsho is a “sharity,” a term coined by creator Mallence Bart-Williams. The boys who make up this collective range in age from 14 to 20, and most were originally members of a band of societal outcasts from an area called “Lion Base.”

Mallence teamed the young men up with local artists, who taught them batik dyeing and traditional embroidery. A sneaker company united with Folurunsho and a collection of kicks were displayed in Paris’s premier department store, Collette. The proceedings from these are used by the boys in Freetown for what is for some their first housing, private tutors and nourishing food. With the help of friends, Mallence documented it all in a book, titled Lion Base, and a soon to be released documentary.

Under the glare of the full moon, in that eerie hour that links night to morning, the women revealed the faces of “producers” Heaven Gate, Long Life, Base and others to the consumers of Paris.

The project’s press release revealed a mirror image:

We confront two individuals that each have 5000 to spend: the woman going to Avenue Montaigne to spend €5000 on a luxury accessory meets [a young man] that has SLL 5000 to spend on his next meal. When building a bridge two extremes are what give it balance and make it stand and sustain.

‘To be or to have?’ is the question we want to raise … from Freetown to Berlin to Paris … ‘Who is rich or poor?’ All is a matter of perspective.

But whose perspective was being demanded on Avenue Montaigne? Any attempt to provocatively interrupt Fashion Week activities with subjects that might make luxury consumers feel momentarily uncomfortable is often excellent fodder for media outlets. A dispute between two fashion giants makes front page. The scarred face of an African young man serves as an opportunity for voyeurism. Never mind the fact that this young man is intimately known to those revealing him.

People kind of like being voyeurs, and without an obvious context to who they’re peering at, would have and probably did denote the images of the boys to the standard “poor African” archetype. Even with a thorough press release, attempts to complicate those images were handled by most, beyond some blogs, by not being reported at all.

* Shamira Muhammad is a freelance writer/journalist based in Paris, France. A recent graduate of NYU’s Africana Studies and Global Journalism program, she has reported across the African Diaspora on subjects as diverse as Jamaican bus conductors and US foreign policy in Africa. (All pictures, except the first one by Muhammad, are by Mallence Bart-Williams.)

October 5, 2012

Friday Bonus Music Break

This week Nigeria–yes the country whose history Rick Ross mangled in his latest music video (Ross should have taken lessons from Chinua Achebe)–turned 52 to this week. Here, the “First Lady of Mavin Records,” Tiwa Savage sings the national anthem of Nigeria on a Nigerian TV show:

London-based Nigerians Afrikan Boy (he used to collaborate with M.I.A.) and Dotstar try their hand at the azonto craze:

And you’re obligatory dose of Nigerian pop:

Brussels-based rapper Pitcho (his family is from the Congo):

Oddisee (born Amir Mohamed el Khalifa)–father Sudanese; mother African-American–channels Bon Iver:

Either Fokn Bois is still on their mission to get Ghanaians (and the world) to be less serious about religion (remember their “Gospel Porn” album) or they’re want just attention:

Anything we missed?

When Solange filmed a music video in a Cape Town township

I had forgotten about American singer Solange Knowles until The Fader shared her new music video for ‘Losing You’ this week, calling it “a killer single.” The music video comes two weeks after another video by Swedish band Little Dragon surfaced on the web. Both videos were recorded in some of Cape Town’s townships. Where Little Dragon’s acoustic session is pretty dull (MTV disagrees) and the band doesn’t even seem to pretend they’re interested in their surroundings, Solange plays around, touring the unnamed township in the company of what appear to be a group of friends (whom she flew down) and an oddly out-of-place group of Sapeurs (it’s not clear whether she flew them down too). In an interview, Solange explicitly refers to the work Italian photographer Daniele Tamagni did on Sapeurs as an inspiration for the styling of the video. Tamagni is one among many photographers who swarmed to Brazzaville and Kinshasa some years ago to shoot the Congolese life-style phenomenon. (Remember the work of Héctor Mediavilla Sabaté, Baudouin Mouanda and Francesco Giusti for example.) Somehow, these kind of photo series on one and the same topic always appear to come in waves. Think also of that bulk of features on Congolese wrestling from around the same time, or in a different context, those on poor white South Africans. One photographer “discovers” a subject, others will quickly follow, and, with some delay, you’ll see the imagery start to circulate in other popular media. It’s what pop is about. (Side note: when will this grittier look on Sapeurs go viral?)

But back to the Solange’s music video. As has become custom around Africa is a Country, I decided to solicit opinion from around the “office.”

Marian Counihan: Township life has never looked so glam. In some ways it feels cheap, it’s like the (re)discovery of the ghetto — but now it’s slightly exotic, and so fresh again. Solange is a bit of a fish out of water (at some points moving like one too). But it’s a nice track, and it’s refreshing to see Africa filmed in a slightly faded pallette instead of the oversaturated one we’re used to — and it’s one that accurately conveys Cape Town’s Africa-for-Europeans feel.

Sean Jacobs: Unless Solange is making a political statement (I am being generous) about xenophobia and panafricanism (by featuring Sapeurs in a video filmed in a South African township). But we know that Cape Town was merely a stand-in. I can’t make out the mix of images and references (especially of the Sapeurs). Otherwise it looks like a series of images patched together. For the Cape Town people: It looks like it was filmed either in Langa or Philippi?

Marissa Moorman: Indeed, it’s hard not to read this as part of the “Come Film in Cape Town” trend. The Little Dragon video at least has some sonic interaction, if no physical movement around the space … but both videos just use these neighborhoods as background, as periphery ghetto chic.

Wills Glasspiegel: I like the tune, love Blood Orange. Seems like Solange should work with Boima at some point, too. The dancing looks a bit off in terms of how it was edited to the music. For some more background re: Solange and Africa, I co-shot this video that she sang on once for a project she was doing for Coke’s clean water campaign in Kenya with Chris Taylor from Grizzly Bear.

Palika Makam: Visually, the video is interesting and I enjoy it — the subdued colors, the fashion, the direction. She worked with Mickalene Thomas, a Brooklyn artist who I’ve actually interviewed for Life and Times before, a site started by Jay Z. The collaboration makes sense since it is her brother-in-law’s website. Mickalene’s work tends to have strong blaxploitation themes and specific pattern choices and color palette — all which you can see in the video. In terms of the content, the location and concept for the video make no sense and have nothing to do with the song. There’s also been some controversy over why she chose to feature those Sapeurs from Congo instead of Cape Town’s Swenkas. I don’t understand why she couldn’t disclose the location. Instead of situating the story and characters within a particular place of importance, the streets and shacks are just a representation of “Africa” or “poverty,” with no real identity.

Marissa Moorman: One of the interesting bits in the Fader interview is the fact that Solange originally wanted to film in Brazzaville but was discouraged because of the cost, ‘drawing too much attention,’ and ‘insurance issues.’ Cape Town makes it easy to film there. US citizens don’t even need visas, so boom — there they go. There is actually something called political risk and insurers have actuarials for this kind of thing. So filming this kind of video is wrapped up in a politics of stabilization — and South Africa trades repeatedly on its relatively sounder stability. And that just bugs me at some level. It disappears in all the flyness of the duds.

Neelika Jayawardane: I’ll second what Marissa said. Visa and immigration restrictions/insurance/political/other bureaucratic measures meant to roadblock life’s natural flows are the ‘real’ to which flyness often responds, with flamboyance as the jailbreak device. So denaturing or escaping the ‘real’ of the misery that such restrictions produce by replacing it with Cape Town is to remove not just the context, but to replace that symbolic space of the ‘real’ with a superficially pretty location — in fact, with a city that actively whitewashes the restrictions it places on freedom, liberty, egalité in an entirely different way. The two things that are juxtaposed here in this video — flamboyance as a response to the breakdown of human value, and Cape Town’s own set of inhuman, yet whitewashed restrictions — do not “call and respond” to each other. I think that’s why the Solange video doesn’t work on subtle levels. And once you know, the juxtaposition is quite jarring.

I’ve often thought that dandies such as the Sapeurs are not too different from their counterparts in late 19th/early 20th C Europe (not the Louis the XVIth type of dandy, who are responding to abundance and the material effluvia of Too Much; I’m referring to the effervescence of subversive gay culture circa Oscar Wilde in the late 1800s/early 1900s).

The Knowles family is known for taking the style signifiers and emptying out the context, no? So I doubt that this history and context matters to them; what sells is a flattened out landscape of signs and symbols. If it requires too much intellectual or emotional involvement, it may not be attractive to the demographic they want to reach, and therefore, not make the piles of money that videos like this usually do.

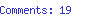

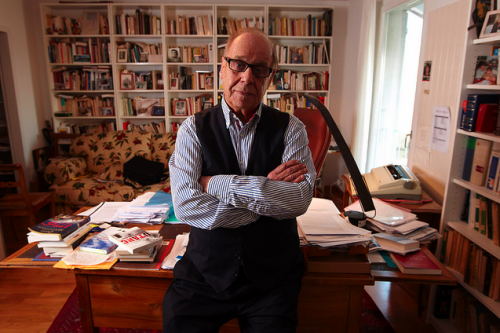

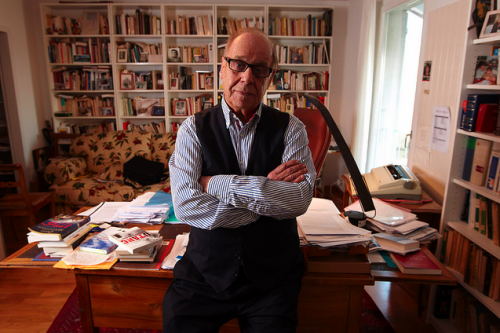

Former UN envoy Jean Ziegler on Third World hunger: “We Let Them Starve”

Jean Ziegler was until recently (2000-2008) the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, and subsequently, in a similar function, he served on the Advisory Committee to the UN Human Rights Council. He is also a vocal critic of global capitalism’s effects on the developing world, especially Africa. The last few days he has been doing the media circuit promoting his new book, “Mass Destruction: The Geopolitics of Hunger” (the French title) or “We Let Them Starve: The Mass Destruction in The Third World” (the German title). There’s no English title available yet. Ziegler is a well-known Swiss author and politician — his writing is prolific and ever since his first publication (Sociology of the New Africa, 1964), he has taken on the cause of the developing world, against imperialism, capitalism, and injustice. In 1964, as a young academic, he chauffeured Che Guevara around Geneva when the Cuban revolutionary visited the UN. His combative and at times polemical style has earned him much admiration, but also vilification, and legal persecution. As a socialist member of the Swiss parliament, he particularly attracted the ire of Switzerland’s liberal-conservatives, closely related to big business, and of course the major Swiss banks, for denouncing their hiding away of stolen funds, such as those of former dictator Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, of those of Jewish people who perished in the holocaust, and of all kinds of dubious origin that ended up in Swiss banks.

Jean Ziegler was until recently (2000-2008) the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, and subsequently, in a similar function, he served on the Advisory Committee to the UN Human Rights Council. He is also a vocal critic of global capitalism’s effects on the developing world, especially Africa. The last few days he has been doing the media circuit promoting his new book, “Mass Destruction: The Geopolitics of Hunger” (the French title) or “We Let Them Starve: The Mass Destruction in The Third World” (the German title). There’s no English title available yet. Ziegler is a well-known Swiss author and politician — his writing is prolific and ever since his first publication (Sociology of the New Africa, 1964), he has taken on the cause of the developing world, against imperialism, capitalism, and injustice. In 1964, as a young academic, he chauffeured Che Guevara around Geneva when the Cuban revolutionary visited the UN. His combative and at times polemical style has earned him much admiration, but also vilification, and legal persecution. As a socialist member of the Swiss parliament, he particularly attracted the ire of Switzerland’s liberal-conservatives, closely related to big business, and of course the major Swiss banks, for denouncing their hiding away of stolen funds, such as those of former dictator Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, of those of Jewish people who perished in the holocaust, and of all kinds of dubious origin that ended up in Swiss banks.

While his fighting spirit, his relentless engagement for justice across the world, and his international standing have earned him respect, he has remained a thorn in the side of Switzerland-based businesses (such as Nestlé*) who have been highly irritated by his denunciation of their profiteering and their active participation in practices that kept developing countries poor and dependent.

With this in mind, it is then quite understandable that business journalist Philip Löpfe’s interview with Ziegler for newsnet, the online presence of the Swiss newspapers Basler Zeitung and the Zürich-based Tagesanzeiger, would be a loaded affair. And yet, the combative and perhaps provocative personality of Ziegler and his engagement with poor countries alone do not fully explain the tendentious nature of the questions he faced. Rather, what shines through in Löpfe’s tone and in the content of his questions is the strained arrogance of those whose profiteering from global misery was usually explained away as natural and which has now, as global neoliberalism struggles and inequalities become more glaring, been opened up to closer scrutiny and contestation.

Some excerpts from the interview, which I translated from the German:

Ziegler: According to the UN World Food Programme, there is enough food in the world for 12 billion people. If today people are still starving, then this is organized crime, mass murder. Every five seconds, one child under the age of ten dies, one billion people are permanently and heavily undernourished.

Löpfe: [Your] book’s title is “We let them starve”. I am not aware that I let anyone starve.

Ziegler: That is true, but we are all accomplices. We allow multinational food corporations and speculators to decide everyday who is eating and living, and who is starving and dying.

What should the individual do? Donate money? Eat less meat?

… It is mainly about becoming politically active in order to put an end to the murderous activities of food speculators and multinationals. We can do so, we live in a democracy.

Food speculation has existed for thousands of years. What is wrong when a farmer seeks insurance against bad harvests or when a baker ensures that his supply of flour is stable?

Nothing. But that is not the point … The commodities market was ‘financialised’. Speculators are making billions, while millions of people starve to death.

[...]

How could we avoid such speculation?

We could exclude all non-producers and non-consumers from the commodities exchange — in this sense only the farmer and the baker, through the commodities exchange engage in trade with each other.

However, the experts have agreed that during emergencies, such as droughts and floods, and so on, commodities exchange and trade should remain open. It was disastrous that during the famine of 2008 some countries blocked the export of rice.

Famines, such as in 2008 and 2011, are additional disasters; they add to the daily massacre of hunger, the so-called ‘silent hunger’. It is true that at the time rice exporting countries such as Thailand and Vietnam closed their borders. Governments were afraid of riots in their own countries. That is understandable. But for a country like Senegal, importing 75% of its rice, it was a disaster.

Why is a country like Senegal forced to import rice? The majority of its population are still subsistence farmers.

It remains a fact that in terms of percentage of the population, there are nowhere more starving people than in Africa. About a third of the population’s men, women and children are permanently undernourished.

Could one not argue in a provocative way that Africa is not starving because of the speculators but because it is too poor for the speculators: there is nothing to be earned there.

No, no. African countries have incredible civilisations, based on agriculture, with much knowledge and very fertile soils.

Why is it that Africa is the continent where most people starve and which imports more than a quarter of its food supply?

Because the colonial pact is still enforced.

Isn’t this a bit too simple? Colonialism is over for more than half a century.

But there still is a small upper class, dependent on rich countries, and extremely corrupt. Again Senegal: The country exports peanuts and at the same time imports three quarters of its food requirements.

Why?

Because the colonial pact was never broken. The Senegalese farmers are forced to grow and exports peanuts because the revenue serves to pay for foreign debt. At the same time, Europe sells its food surplus at dumping prices on the African markets. How can a small farmer survive under these conditions?

African farmers are not very productive. Their productivity is less than 10 percent of Europe’s agriculture. Are they not just lazy?

On the contrary. Nobody works harder than farmers in Africa. They just cannot thrive because they are not supported: no irrigation, no seed, no draft animals, no tractors, no fertilizer, nothing.

So there you have it. Like the now jobless Greeks, if only those poor people weren’t so lazy…

But there is more to this story. Löpfe’s ‘provocative’ questions — especially his last one — are, if not racist, then surely a thinly disguised nod to the neoliberal, corporate raiders who have recently acquired one of the papers in which the interview was published. Thus, both papers are now owned by holding companies in which business tycoon Tito Tettamanti controls the majority of shares.

Georges Bindschedler, co-investor in the rather cynically called ‘Medienvielfalt Holding’ (Media Diversity Holding) makes it clear why it was necessary to acquire the newspaper.

In an interview last year, he elaborated on their ‘mission’. He suggests that the ‘liberal music’ is not heard loud enough in the Swiss media landscape, and hence Swiss voters fail to understand important political issues, and vote the wrong way, one might add. In particular, he was referring to the rejection by Swiss voters of the rationalisation of a national health care system earlier this year, which according to some analysts would have led further down the slippery slope to a two-tier system — one for the rich, and one for the poor.

As everywhere in the world, corporate control of the media is not about safeguarding the diversity of opinions, as he claims, but about propagating more neoliberal, pro-business values and ideas.

Perhaps it is a sign of the times that even in Switzerland, the sheltered island of wealth and prosperity, neoliberal capital feels the need to step up its propaganda efforts.

* Nestlé, the multinational food company who would package air and sell it if they had the technology, has its global headquarters in Vevey, Switzerland. Xstrata and Glencore, after their impending merger the world’s biggest trader, or rather speculator, in commodities, including food, is domiciled in Baar, Switzerland. Glencore’s founder, Marc Rich, built the company partly from profits accumulated by breaking the US oil embargo of Iran in the late 1970s.

Jean Ziegler: “We Let Them Starve”

Jean Ziegler was until recently (2000-2008) the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, and subsequently, in a similar function, he served on the Advisory Committee to the UN Human Rights Council. He is also a vocal critic of global capitalism’s effects on the developing world, especially Africa. The last few days he has been doing the media circuit promoting his new book, “Mass Destruction: The Geopolitics of Hunger” (the French title) or “We Let Them Starve: The Mass Destruction in The Third World” (the German title). There’s no English title available yet.Ziegler is a well-known Swiss author and politician — his writing is prolific and ever since his first publication (Sociology of the New Africa, 1964), he has taken on the cause of the developing world, against imperialism, capitalism, and injustice. In 1964, as a young academic, he chauffeured Che Guevara around Geneva when the Cuban revolutionary visited the UN. His combative and at times polemical style has earned him much admiration, but also vilification, and legal persecution. As a socialist member of the Swiss parliament, he particularly attracted the ire of Switzerland’s liberal-conservatives, closely related to big business, and of course the major Swiss banks, for denouncing their hiding away of stolen funds, such as those of former dictator Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, of those of Jewish people who perished in the holocaust, and of all kinds of dubious origin that ended up in Swiss banks.

Jean Ziegler was until recently (2000-2008) the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, and subsequently, in a similar function, he served on the Advisory Committee to the UN Human Rights Council. He is also a vocal critic of global capitalism’s effects on the developing world, especially Africa. The last few days he has been doing the media circuit promoting his new book, “Mass Destruction: The Geopolitics of Hunger” (the French title) or “We Let Them Starve: The Mass Destruction in The Third World” (the German title). There’s no English title available yet.Ziegler is a well-known Swiss author and politician — his writing is prolific and ever since his first publication (Sociology of the New Africa, 1964), he has taken on the cause of the developing world, against imperialism, capitalism, and injustice. In 1964, as a young academic, he chauffeured Che Guevara around Geneva when the Cuban revolutionary visited the UN. His combative and at times polemical style has earned him much admiration, but also vilification, and legal persecution. As a socialist member of the Swiss parliament, he particularly attracted the ire of Switzerland’s liberal-conservatives, closely related to big business, and of course the major Swiss banks, for denouncing their hiding away of stolen funds, such as those of former dictator Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, of those of Jewish people who perished in the holocaust, and of all kinds of dubious origin that ended up in Swiss banks.

While his fighting spirit, his relentless engagement for justice across the world, and his international standing have earned him respect, he has remained a thorn in the side of Switzerland-based businesses (such as Nestlé*) who have been highly irritated by his denunciation of their profiteering and their active participation in practices that kept developing countries poor and dependent.

With this in mind, it is then quite understandable that business journalist Philip Löpfe’s interview with Ziegler for newsnet, the online presence of the Swiss newspapers Basler Zeitung and the Zürich-based Tagesanzeiger, would be a loaded affair. And yet, the combative and perhaps provocative personality of Ziegler and his engagement with poor countries alone do not fully explain the tendentious nature of the questions he faced. Rather, what shines through in Löpfe’s tone and in the content of his questions is the strained arrogance of those whose profiteering from global misery was usually explained away as natural and which has now, as global neoliberalism struggles and inequalities become more glaring, been opened up to closer scrutiny and contestation.

Some excerpts from the interview, which I translated from the German:

Ziegler: According to the UN World Food Programme, there is enough food in the world for 12 billion people. If today people are still starving, then this is organized crime, mass murder. Every five seconds, one child under the age of ten dies, one billion people are permanently and heavily undernourished.

Löpfe: [Your] book’s title is “We let them starve”. I am not aware that I let anyone starve.

Ziegler: That is true, but we are all accomplices. We allow multinational food corporations and speculators to decide everyday who is eating and living, and who is starving and dying.

What should the individual do? Donate money? Eat less meat?

… It is mainly about becoming politically active in order to put an end to the murderous activities of food speculators and multinationals. We can do so, we live in a democracy.

Food speculation has existed for thousands of years. What is wrong when a farmer seeks insurance against bad harvests or when a baker ensures that his supply of flour is stable?

Nothing. But that is not the point … The commodities market was ‘financialised’. Speculators are making billions, while millions of people starve to death.

[...]

How could we avoid such speculation?

We could exclude all non-producers and non-consumers from the commodities exchange — in this sense only the farmer and the baker, through the commodities exchange engage in trade with each other.

However, the experts have agreed that during emergencies, such as droughts and floods, and so on, commodities exchange and trade should remain open. It was disastrous that during the famine of 2008 some countries blocked the export of rice.

Famines, such as in 2008 and 2011, are additional disasters; they add to the daily massacre of hunger, the so-called ‘silent hunger’. It is true that at the time rice exporting countries such as Thailand and Vietnam closed their borders. Governments were afraid of riots in their own countries. That is understandable. But for a country like Senegal, importing 75% of its rice, it was a disaster.

Why is a country like Senegal forced to import rice? The majority of its population are still subsistence farmers.

It remains a fact that in terms of percentage of the population, there are nowhere more starving people than in Africa. About a third of the population’s men, women and children are permanently undernourished.

Could one not argue in a provocative way that Africa is not starving because of the speculators but because it is too poor for the speculators: there is nothing to be earned there.

No, no. African countries have incredible civilisations, based on agriculture, with much knowledge and very fertile soils.

Why is it that Africa is the continent where most people starve and which imports more than a quarter of its food supply?

Because the colonial pact is still enforced.

Isn’t this a bit too simple? Colonialism is over for more than half a century.

But there still is a small upper class, dependent on rich countries, and extremely corrupt. Again Senegal: The country exports peanuts and at the same time imports three quarters of its food requirements.

Why?

Because the colonial pact was never broken. The Senegalese farmers are forced to grow and exports peanuts because the revenue serves to pay for foreign debt. At the same time, Europe sells its food surplus at dumping prices on the African markets. How can a small farmer survive under these conditions?

African farmers are not very productive. Their productivity is less than 10 percent of Europe’s agriculture. Are they not just lazy?

On the contrary. Nobody works harder than farmers in Africa. They just cannot thrive because they are not supported: no irrigation, no seed, no draft animals, no tractors, no fertilizer, nothing.

So there you have it. Like the now jobless Greeks, if only those poor people weren’t so lazy…

But there is more to this story. Löpfe’s ‘provocative’ questions — especially his last one — are, if not racist, then surely a thinly disguised nod to the neoliberal, corporate raiders who have recently acquired one of the papers in which the interview was published. Thus, both papers are now owned by holding companies in which business tycoon Tito Tettamanti controls the majority of shares.

Georges Bindschedler, co-investor in the rather cynically called ‘Medienvielfalt Holding’ (Media Diversity Holding) makes it clear why it was necessary to acquire the newspaper.

In an interview last year, he elaborated on their ‘mission’. He suggests that the ‘liberal music’ is not heard loud enough in the Swiss media landscape, and hence Swiss voters fail to understand important political issues, and vote the wrong way, one might add. In particular, he was referring to the rejection by Swiss voters of the rationalisation of a national health care system earlier this year, which according to some analysts would have led further down the slippery slope to a two-tier system — one for the rich, and one for the poor.

As everywhere in the world, corporate control of the media is not about safeguarding the diversity of opinions, as he claims, but about propagating more neoliberal, pro-business values and ideas.

Perhaps it is a sign of the times that even in Switzerland, the sheltered island of wealth and prosperity, neoliberal capital feels the need to step up its propaganda efforts.

* Nestlé, the multinational food company who would package air and sell it if they had the technology, has its global headquarters in Vevey, Switzerland. Xstrata and Glencore, after their impending merger the world’s biggest trader, or rather speculator, in commodities, including food, is domiciled in Baar, Switzerland. Glencore’s founder, Marc Rich, built the company partly from profits accumulated by breaking the US oil embargo of Iran in the late 1970s.

October 4, 2012

10 films to watch out for, N°5

‘One Man’s Show’ is the latest film by Newton I. Aduaka (probably best known for his 2007 film ‘Ezra’) with Emile Abossolo Mbo as the comedian who has to confront his children and past relationships after hearing he has cancer. (Two more teasers: here and here.) Next, ‘Maj’noun’ by Tunisian director-cinematographer Hazem Berrabah is “an abstract love story” told through contemporary dance, somewhat inspired by the stories about Qays ibn al-Mulawwah and Layla Al-Aamiriya, and the relation between Louis Aragon and Elsa Triolet:

‘Morbayassa’ is director Cheick F Camara’s second long-play feature, starring singer Fatoumata Diawara (left). The film follows Bella, a Guinean woman who gets trapped in a prostitution network. Recorded in Dakar, Conakry and Paris, it is in its post-production phase. Here’s the crowdfunding page.

‘Morbayassa’ is director Cheick F Camara’s second long-play feature, starring singer Fatoumata Diawara (left). The film follows Bella, a Guinean woman who gets trapped in a prostitution network. Recorded in Dakar, Conakry and Paris, it is in its post-production phase. Here’s the crowdfunding page.

Solomon W. Jagwe (from Uganda) calls ‘Galiwango’ “a 3D Animated Gorilla Film” doubling as “a wildlife conservation effort with a goal of reaching out to the Youth”:

Another animation film (series for TV), ‘Domestic Disturbance’ is the work-in-production of Kenyan filmmaker Gatumia Gatumia (who trained in Canada):

‘Le Thé ou l’Électricité’ (“Tea or Electricity”) by Jérôme le Maire is a documentary set in the small, isolated village of Ifri, enclosed in the Moroccan High Atlas Mountains. For over three years, the director captured and traced the outlines and arrival of the electricity network in the village:

‘Another Night on Earth’ follows the lives of a selection of Cairo taxi drivers during the 2011 Egyptian uprisings:

‘Congos de Martinique’ is a film by Maud-Salomé Ekila portraying “Congolese” descendants of people who were shipped as slaves to the French Antilles (and Martinique in particular). No English subtitles yet:

‘African Negroes’ is a short South African documentary about a soccer team that was used as a front for political activities in the small Karoo town of Graaff-Reinet:

And ‘Into the Shadows’ aspires to give insight into Johannesburg’s inner-city life, focussing on migrants’ lives and talking to different stakeholders:

* Our previous new films round-ups: part 1, part 2, part 3 and part 4.

October 3, 2012

Africa is a Horse

In the ambient stale haze of my father’s fags, among the empties and forlorn pages of racing print stained in stout, I have found myself glancing through the debris of an afternoon’s handicapping, pausing at the almost impenetrable nomenclature and knowledge contained therein, developing a random yet fond attachment to certain horses.

You couldn’t make up the outrageous names given to some beautiful beasts. Most though are fortunate to acquire quaint or jolly designations. A few have topical names, such as the obvious: Obamarama or Obama Rule. There are five thoroughbreds with an Obama name or prefix. More interestingly are the increasing numbers of horses representing Africa. I am not referring to horses bred or training in Africa, of which there are some notable champions and contenders, but rather the growing trend of adding an African appellation to a horse’s name.

A serious punter never picks a horse by name. It is the trainer, the booked jockey, the weight to be carried, the past course and distance record, breeding and the prize money that inform deliberations on equine investments. The name may provide a key clue to a horse’s family tree, but more often it is happenstance or a cute choice by an owner or syndicate. So what is it about Africa and why is it trending on birth certificates at stud farms?

Africa may register little in horse racing history, though it would be wrong to assume African names are a recent equine development. Horse racing aficionados have long had a penchant for placing an African prefix to a horse’s name. One could easily guess the names of such creatures: African Safari, African Sunset, African Queen and African Warrior are all horses who have raced across eras and jurisdictions, evoking for the casual rail bird or equine sophisticate that sultry yet wild expansive continent starring Stuart Granger and Deborah Kerr or Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O’Sullivan or for the discerning documentarian that glorious space of savannah and swamp as narrated by Lorne Greene.

Romantics and voyeurs have not had a historical monopoly over African horse names, however. The more down to earth breeders and owners have also kept the handicapper busy, reminding punters what Africa has really been all about. Preciously named horses such as African Diamond and African Gold have promenading history in the paddock. More recently such shiny animals have been joined by the likes of African Oil, a 2 year old bay colt bred in France who slickly strutted his stuff across England’s green and pleasant turf this past summer.

But now a whole other generation of curious about Africa horse breeders and owners are upon us. Those with the power to own and name a horse have new experiences and influences to call upon. The post-Band-Aid-Jet-Set has largely upped stakes from camp Africa and would never knowingly own a blood diamond. They cruise around in a cacophony of Bono interviews and eponymous Paul Simon tunes. George Clooney movies clutter their DVD rack and they share Nick Kristof on Facebook, often. Kristof endorsed paperbacks can be found on the back seat shag of the Range Rover, though they prefer not to deface the rear of their souped-up jalopy with “Save Darfur” bumper stickers. This is the generation that feels Africa in ways their tweedy parents never did. This generation is not about exploitation and cheering on mercenaries and or Tarzan, though they prefer not to mention mining shares their grandparents cautiously placed in their portfolios. The modern horse owner wears Hunter Wellies — a conscience and sustainable fashion choice, which also provide jobs in Ghana’s rubber industry. The modern horse owner has hiked up Kilimanjaro and raised cash for noble causes. The modern horse owner supported the No Fly Zone and NATO sorties over and freedom for Libya.

And so it follows there are now whole new categories of African horse names. We have African Action, African Appeal and African Art. There is even an Africanist, a 3 year old grey roan colt, who ran sixth when last up at Churchill Downs. Africanist was sired by the prolific stallion, Johannesburg, who was noteworthy for winning a Breeders Cup Juvenile, and currently stands at stud in Japan. There are even African names set aside for just the right future foal, such as African Hope.

It is not just Africa or African that is en vogue. Horses named after African countries are also relatively commonplace these days. For instance, the next running of the Melbourne Cup on November 6th, the world’s richest handicap race, “the race that stops a nation,” with over 6 Million Australian dollars in the purse, has a 4 year old bay gelding called Ethiopia entered. Ethiopia is proven Group 1 (highest race classification) winner, taking last year’s Australian Derby at the Royal Randwick track in Sydney.

Most African countries now have at least one horse name after it. Burkina Faso is one of the few exceptions. Maybe one day if I hit the sweepstakes, I will join the fraternity of horse owners and name my horse, Thomas Sankara. It would be quite the scene to see a horse named after a Pan-Africanist Revolutionary Marxist have his nose rubbed by the Queen of England in the winning circle at Royal Ascot or draped in garlands at Churchill Downs in the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

October 2, 2012

The Danger of a Single TED Talk

Africa.com have made a movie that’s going to change the way you think about Africa. If the trailer is any indication of what the film’s about, then we’ve reached only one conclusion: Africa is officially boring. We’ve blogged about this kind of boosterism before, including Vogue Italia’s special “Rebranding Africa” issue earlier this year, which decided UN General Secretary Ban Ki-Moon should be the continent’s new face, salivated over Nigeria’s notoriously corrupt oil minister, and scrupulously avoided any mention of anything “sad, trashy or poor”.

To cut a long critique short, we’re pretty sure Africa isn’t a brand and we find the clamour for “positive news” from Africa inane and condescending. Plus if Africa.com’s movie really does go on for an hour, as has been threatened, it’s going to be unbearable.

Who exactly is the audience for this kind of thing? It seems to be about attracting investment, but the style of the film is more likely to appeal to the development crowd — people who likely already consider themselves availed of a “positive” idea of Africa — than to hard-nosed capitalists. It will also appeal to all those Nigerians who were so outraged to see Lagos’ poor turn up on MTV the other day through the offices of Rick Ross, apparently making them look bad.

In the old days we got starving (or sometimes smiling) children and Bono. That was the age of aid. Nowadays it’s all about trade and what you get is this weird neoliberal romance where everybody’s middle class and desperate to show you their mobile phone.

The Africa.com initiative is very much a project conceived in, and aimed at, the United States (their CEO used to be a Goldman Sachs banker) and I can only think that on some level it arises (belatedly) from an anxiety at the way the Americans have been unceremoniously elbowed aside by the Chinese in recent years when it comes to making money in Africa.

The movie promises the usual “pro-Africa” cast of characters, and of course that means sitting through yet another viewing of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “The Danger of a Single Story”. (It would be nice if Adichie did another one called “The Danger of a Single TED Talk” because the army of online disciples who force everyone to watch “The Danger of a Single Story” over and over again show no sign of letting up in their exuberant rejection of her central argument in that video.)

We also get Nigeria’s neoliberal finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala (Diezani Allison-Madueke’s invitation to appear in the film must have got lost in the post). Okonjo-Wahala cracks a joke about investment in telecoms, the point being that Nigeria has a lot of investment in telecoms but “nobody” knows about it. The joke isn’t all that funny because actually loads of people already know about Nigeria’s telecoms boom. Even Arsenal FC seem to be aware of it.

No doubt there’s plenty more of this sort of stuff to come, but this “new” way of looking at Africa already feels like it’s out of date.

October 1, 2012

Nollywood: Nigeria’s Mirror

Lagos poet, Odia Ofeimun

This past summer on a rainy June afternoon, I spent a few hours interviewing Nigerian poet and critic, Odia Ofeimun. I met him while co-producing a radio documentary about Nollywood (streaming in full here). Odia has been writing about life in Lagos for the last forty years. His observations reflect many of the key tensions in contemporary Nigerian life. The following quotes are culled from my interview with him (some audio of that interview embedded below) at his home in the Oregun section of Lagos.

Odia Ofeimun: “Lagos is a city you get to and feel like you can achieve anything in the world. It is not the most beautiful city, but it has its seductions. It is a society that sucks you in, and even when you are not part of the shaking or the moving of the city, you begin to have the feeling that you too will be there one day.”

“There is a headiness the average Lagosian has — you do not really feel that the big man, no matter how big he is, is your boss, the man you call “Oga.” And he, the man you call “Oga,” knows that you do not really regard him as your master. “Oga” does mean master, but the average Lagosian who calls you “Oga” is just doing it to silly you. Those who take him seriously are fools.”

On Nollywood

“When Nollywood gets it right, there is something marvelous in having your stories told in a way that you can just lap up like syrup. Even when you know that the story has been badly told, you still want to know what comes next. There is a self-flattering in it for many Africans. And beyond that, people are generally looking for answers for questions that they don’t have answers to, and you can’t be too sure whether the next film might provide an answer.

People swallow it like gospel. In some African countries, when an original film star is visiting, you would think it is a head of state — and that is part of what makes it bothersome for me. Young people don’t get their own history told in the right way. In many Nollywood films, it is not about getting it right. It’s not about representation.

Many people do not like the word representation. But there is a need for us to know what a human face looks like before you bring to it all the jazziness that artists sometimes bring to it. In art, if you did not have those well-realized Roman noses and facial structures, the kind of things that Picasso had to do would be more difficult to understand. It’s like trying to understand African art without seeing those original Ife forms that were styled to match nature.

The standard Nollywood narrative pays very little attention to knowledge as knowledge, in which case you are not allowing the storytelling to dictate what is knowable. There is a reality before the story.”

On the portrayal of traditional culture in Nollywood

“There is a sense in which we have not quite taken traditional society seriously enough. The Westerner who moved to Africa drew a line and said this is Western and this is African, but what we needed to do was to do a proper matching. You look at a Nollywood film of pure fetish, and it does not reveal the underlying science. All of these issues about importing the West or not importing the West — that’s running away from the problem. There were inoculations in Africa against whooping cough, against all manner of diseases, before Western science brought their own methods of inoculation. Because our universities have not developed enough to the point of actually taking the knowledge of the English language into the traditional and taking the knowledge of the traditional into the English, we have a sharp divide between the two, which has made it very difficult for so called African science to become a part of the mainstream of world of science.”

“Nigerians discuss federalism like it was something imported from outer-space, but I’ve seen many traditional African societies in which federal principles were rigorously adhered to — we’ve just not managed to study them enough as federalism. We have studied them as traditional African culture, and we distinguish them from the other forms as if the two can never meet. We end up bastardizing the original without having made good use of the Western fields of discourse. In my view this creates a lot of problems. And of course, people try to solve the problems by going into magical realism in fiction, or animist realism, which is sometimes just a way of running away from what you don’t understand. So you find a lot of padding in some novels which tell you next to nothing about what is really happening.”

Religion in Nollywood

“Much of what you see in Nollywood in relation to religion is hogwash because the human capacity to solve problems is denied. The power to make things happen is given to God, who already gave you powers to use. It’s as if you are denying that God gave you those powers when you credit to him every evil or good that happens. In Nollywood, that is the way it happens. Problems that have direct objective and scientific solutions are made to appear so outlandish, so out of this world, so otherworldly, that it is solely by appealing to God that they get solved.

There are psychological problems that have direct solutions. Somebody living alone who has little oxygen may have nightmares. It is biological. But in Nollywood, when you come across someone who lives in this situation, rather then taking a look at the circumstances of that individual, you appeal to God. Every nightmare is interpreted as a spiritual attack which some pastor will deal with. People have stopped using their brains. Societies like that are asking to be colonized. They are asking for forces outside their own orbit to intervene in their environment. So much is granted to that otherworldly power that the powers that individuals have always been given by their maker are neglected and allowed to decay. Nollywood is a good example of how Africans are taught not to use their minds. I am just hoping that some smart kid, some smart young women or man, will enter that business and turn it upside down. It will be the radical revolution, the break and rupture that will make a difference.”

The role of criticism

“Much of what I am reading still fails to engage Nollywood in the way that Nollywood should be engaged, because it does not deal with the society that is producing Nollywood. The two need to be looked as connected — Nollywood as the product of our society. And you need to look at that society to see how it is either engendering, encouraging, or distorting what can be produced.”

“Nollywood films are as underdeveloped as Nigerian society, and when you watch them, you see all the forms of underdevelopment, both technically and socially. If you really want to know what is going wrong with Africa, Nollywood shows it: the very unscientific approach to problem solution is there, brazen. And the self deceit that is part of communal life is there, also brazen. So it is a case of the mirror that is itself problematic. What it tells you is not exactly what you ought to know, but without the mirror you would probably see nothing. And that’s where the relevance of Nollywood comes in. We manage to see something, even if it’s not what we should be seeing.”

“But I must confess I am sometimes kind to Nollywood because I don’t want to destroy it. It’s like: this is the only thing we’ve got, we might as well not destroy it. But again, we don’t have the media that can do it well. Everyday, newspaper attention to Nollywood is at the same time propaganda and advertisement, before it is an artistic assessment. And therefore, much of it is not valuable from the standpoint of the creation of standards. The way that the universities have started to move into it, and actually creating Nollywood subsections in the departments of film, can help. But in Nollywood, you have a situation in which those who would use the highest of standards have to go through media that would not accommodate those standards properly.

We also appear not to have acquired that academic sense of objectivity, which can take a hard look at the culture and go after it. Because, as I tell some of my friends, if you put culture or ancestors on the line, I will go after them. There is no reason I should worry about whether your ancestor was better then mine. We judge the ancestor by what the ancestor did in relation to certain values. And if your or my ancestor cannot meet those values, too bad for him or her.

At the end of the day, it is the capacity to do a critique that sometimes engenders the capacity to create. The best critique of a work of art could also be a work of art.”

To hear the full 50 minute radio documentary, ‘Nollywood: Nigeria’s Mirror’, visit http://soundcloud.com/afropop-worldwide/sets/nollywood.

Africa is a Country and London’s Film Africa 2012 Festival

This year Africa is a Country is partnering with Film Africa, London’s only annual African film festival to review some of the films that will be screening 1-11 November. Perhaps this should also be filed partly under “Shameless Self-Promotion” since I’m a programmer at the festival. However, AIAC’s writers/bloggers will pre-review films going to London, many of them UK premieres. Some of the highlights of the programme are:

This year Africa is a Country is partnering with Film Africa, London’s only annual African film festival to review some of the films that will be screening 1-11 November. Perhaps this should also be filed partly under “Shameless Self-Promotion” since I’m a programmer at the festival. However, AIAC’s writers/bloggers will pre-review films going to London, many of them UK premieres. Some of the highlights of the programme are:

A screen seminar, which was born here on AIAC in the form of a 5 Alternative Film Collectives post. At this event at London’s Rich Mix, Film Africa will screen the best of the Slum TV film festival in Kibera, alongside videos from the Mosireen Collective. Also screening is ‘Upendo Hero’, a new film by Urban Mirror about the reclamation of public space in Nairobi:

The opening night screening is Nairobi Half Life, just announced as Kenya’s nomination for Best Foreign Film for this year’s Oscars. The film was produced by One Fine Day productions, an initiative by German super-director Tom Tykwer (soon to release ‘Cloud Atlas’) to unearth new Kenyan talent.

Also showing is the moving, disturbing documentary Call Me Kuchu, which follows the struggles of the LGBT community in Uganda, and its figurehead, David Kato, who was brutally killed last year.

Otelo Burning, Sara Blecher’s first fiction feature (her previous film was the documentary Surfing Soweto), a film about actual surfing and Apartheid:

And Sons of the Clouds: The Last Colony, about the continued domination and persecution of the Saharawi people of Western Sahara by Morocco (featuring famed Spanish actor Javier Bardem):

* For full film listings, visit www.filmafrica.org.uk, or watch this space for film reviews from the AIAC team.

Film Africa is also on Twitter: @FilmAfrica and #FilmAfrica2012.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers