Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 523

September 12, 2012

Dutch to elect the ‘King of Africa’

Guest Post by Serginho Roosblad

Today the Netherlands is holding general elections. Although the global economic crisis and its effect on the Dutch economy dominate these elections, some parties want to make this about Africa.

It might come as a surprise, but these general elections are the fifth in a ten year period. A time in which the Netherlands went from one of the most left-wing governments it ever had (from 2007 to 2010), to the most right-wing ever, which followed right after, and which stayed in office until April this year, a mere 555 days.

To some it might seem as the purest example of how a healthy democracy should work; when things get rough, members of a government coalition pull the plug and leave it to the people. To others it may prove that the Dutch are spoiled rich people without any real problems.

The Netherlands, a country that sells itself as being peaceful, stable, prosperous and a champion of human rights, is beginning to look like one of ‘those politically unstable African countries,’ often invoked in its media and by its politicians.

And what would The Netherlands, now that it joined the ranks of the so-called ‘Banana Republics’ be without a proper, strong leader (because that’s what banana republics have)? Well, not to worry. If Emile Roemer, leader of the Socialist Party (SP), would become prime minister, “Africa would be just fine.” This prediction comes from the notorious politician Geert Wilders, leader of the Party for Freedom (PVV). In a recent debate on public radio, Wilders called Roemer the “King of Africa”. And a week before that, Wilders thought that “Africa would be happy with someone like Roemer as prime minister of the Netherlands.” If you’re wondering why, according to Wilders, the leader of the Socialist Party deserves the title “King of Africa”… the answer is development aid. Basically Africa is an election proxy.

In short, the right-wing PVV wants to stop giving development aid and start breaking down trade barriers. The latter sounds noble. But don’t forget, the PVV is the same party that wants an immigration stop on people from Islamic countries, proposed taxes on Muslim women who wear a hijab, wants to ban the Koran (which has been compared by Wilders to Hitler’s Mein Kampf) and wants the Netherlands to step out of the European Union, in order to regain sovereignty, especially on immigration policy.

The PVV, a party which one in five Dutch citizens voted for during the last elections, is your average right-wing populist party that you find throughout Europe. To them, Islam is not a religion, but is a ‘totalitarian ideology’, whatever that may entail. So no wonder that the PVV and its leader don’t ‘want to help Africa.’ The Dutch are number one and the rest can go to … Africa for that matter. But not so fast.

Before this godforsaken continent blasts itself into oblivion with their numerous civil wars and what not, the PVV and its voters (and some in the Dutch media) care about some Africans–well, white South Africans, their “brothers,” or let say their distant cousins. If we’re to believe the PVV’s party program, Afrikaans–the language spoken by, but most certainly not exclusively, Afrikaners–is in danger. Grave danger. According to the PVV:

Afrikaans is closely related to the Dutch language. The language spoken in South Africa and Namibia is continuously being marginalized. The Netherlands [should] defend Afrikaans and those who speak it for example via embassies and the Taalunie. [The Taalunie is the Dutch Language Union, comprised of the three countries where Dutch is an official language.]

What the PVV, most of its supporters and probably 99 percent of the Dutch are unaware of, is that those for whom Afrikaans is their mother tongue are in most cases either Muslim, and not white. The very religion Geert Wilders and the PVV are so against. It will then probably be a surprise to them that early writings in Afrikaans are about the Islam and written in the Arabic script.

And if this is not enough, earlier this year, a member of the party, Martin Bosma, visited South Africa to offer some sort of support to the language and the people that speak it. But even the local whites found him to rightwing. Directly upon arrival, Die Afrikaanse Taalraad (the Afrikaans Language Council) made it clear that it did not want anything to do with Bosma for the mere fact that he and his party are anti-Islam. And to make matters worse, in a column in Dutch newspaper Het Parool, Bosma created the impression that he longed back to the days of apartheid when he said:

It is regrettable that the leftist Netherlands helped putting the ANC into power. Afrikaans and the Afrikaner people will most probably be destroyed. Thank you very much Ed van Thijn for your selfless idealism. [Ed van Thijn was the mayor of Amsterdam from 1983 to 1994 and a prominent member of the Dutch anti-apartheid movement.]

Populism reigned supreme in the PVV’s election campaign and their use of their white ‘innocent’ distant relatives being threatened by the swart gevaar ["black threat"], even though not mentioning it explicitly, most surely fits into their agenda. It is unlikely that the intention of trying to ‘save’ Afrikaans will have any effect on the amount of seats the party will win; their anti-Islam and Eurosceptic ideology is doing it for them.

Of course it is easy to criticize a right-wing populist political party and the use of Africa in their election rhetoric. And looking at the other parties, it turns out that the PVV is not the only one misrepresenting Africa for political gain. Across the Dutch political spectrum, a number of parties, during the campaigns have used ‘Africa’ as metaphor to either evoke a sentiment, present themselves as saviours for the doomed or simply to demonize a political opponent (and in the course also Africa). For example, in a short and snappy 140 character tweet, Jolande Sap, leader of GreenLeft, sneered at Liberal Prime Minister Rutte:

Selfishness rules with Rutte. 70% cut on development cooperation breaks with Dutch tradition of international solidarity. Fair chances for children also in Africa.

Reading through the election program of the Green Party, it is interesting that there is no mention of ‘Africa’ whatsoever. So what its leader actually means with ‘fair chances’ is not clear. Does she mean fair chances in a bubble-blowing contest? For the party to be talking about fair chances, it should start giving the ‘children of the monolithic block of blackness’ the fair chance not to be framed as hopeless and in urgent need of Dutch help.

Indeed, the Christian Union, a party which labels itself as ‘Social Christian’ knows this. In its party program we read that “[i]nternational righteousness is more than only taking care of the poor in for example Africa.” But similar to GreenLeft, the use of Africa clearly serves as a way to illustrate an image from where the party distances itself from, to be looking like the messiah of Africa.

No, the ‘real’ messiah is the Labor Party (PvdA) which, through an ‘independent’ NGO, annually organizes the ‘Africa Day’. But ‘Africa’ is one big, black scary place; it is basically one big Somalia. As the PvdA writes in its party program: “[…] Our [ship] crews are also exposed to the threats of pirates off the coast of Africa.” The coast of Somalia of course approximates roughly one percent of the continent’s total coastline.

Again, these examples will not make the difference in whoever wins or loses the elections. But it does show that the image and misrepresentation Africa is deeply rooted in Dutch society.

* Serginho Roosblad is a journalist for the Dutch World service, Radio Netherlands Worldwide, where he produces and presents the weekly news and current affairs radio show Bridges with Africa. Recently he graduated from the University of Cape Town with a degree in African Studies. He tweets as @SRoosblad.

September 11, 2012

Rhys Ifans vs. ‘The Voodoo Mama’

The Welsh actor Rhys Ifans is best remembered (a lifetime ago now) as Hugh Grant’s fictional roommate in “Four Weddings and a FuneralNotting Hill” And he has a decent career in Hollywood, so it was a surprise to see him pop up in the “short film” on Youtube: “Rhys Ifans vs. The Voodoo Mama.”

For some background, we have the Youtube description of the film: “This laugh out loud comedy is a battle of the sexes at a ghetto bus stop, where a Voodoo Mama (Bilonda Mfunyi) destroys the family jewels of a sexual bully (Rhys Ifans) by using Voodoo Mama Hot sauce. All is at stake in this fun battle over his balls. Do you have the balls for it?”

And there’s this from the director in an short interview with IFC:

We shot the film in a rundown, drug-ridden ghetto in Palma de Mallorca. Rhys was on vacation but was kind enough to lend me his time and talent. Rhys is so passionate about acting that when he likes a piece, I think the important thing for him is to shoot it. I mean, which actor works on their vacation? That’s real passion!

Unfortunately, the internets aren’t very helpful. Everybody just forwards it.

So as we’ve done before (the discussion of Coldplay’s “Paradise” refers) I emailed the AIAC collective, to get their opinions. First up was ‘kola.

‘kola: Watched it three times and apart from the vivid cinematography (and the southern belle pimping of the lady), I really did not get it … Eggs and nerdish weirdos?

Boima Tucker: So much just from the description that I can’t even talk about the film. I was in Palma this summer visiting family (a summer trip I’ve been taking my whole life) and all I could notice is how diverse it was becoming. So many mixed race-culture kids. In the 1980′s I was the only one.

Now in this film, that diversity, which is sometimes vilified in mainstream Spanish society and which should be celebrated to combat the misinformation that permeates nationally, is a site for drug-ridden ghetto films on black American southern stereotypes played out by African immigrants and Northern Europeans on holiday.

Megan Eardley: Our protagonist doesn’t like the creep greasy white guy licking chocolate like that so she grabs a white balled object and, voodoo magic–one object stands in for another, she bites his balls off. Who is this fun for? How am I going to put hot sauce on egg products now? But Boima, just think of the branding opportunities–Voodoo Mama, as American as Aunt Jemima.

Neelika Jayawardane: This film is what I’ll be showing next time some random Euro says in wide-eyed wonder, “Why did you choose to live in America? They are so racist there!”

Tom Devriendt: Looks like it was shot in Corea (the neighbourhood), but it might as well be any other rundown, neglected part of any other city. Belgian-born Bilonda Mfunyi-Tshiabu also has a singing career.

Boima Tucker: Corea is a walking distance away from my Abuela’s house… I don’t think I’ve been there before though. I stand corrected on assuming Ms. Mfunyi-Tshiabu was a local hire, while Mr. Ifans was purely on vacation. Perhaps she was on vacation too.

Here’s a brief bio on the director, not to pick on him personally, but it’s interesting that he’s an American-Austrian born and raised in Mallorca and trained in San Francisco and Philly.

Even though it definitely could have taken place anywhere, I still think the context in which it was made matters. The director is a young Mallorquín. He’s got Austrian and American parents in a place that’s always existed on the crossroads between Europe, Asia, and Africa. Today, they’re going through an identity crisis as Germans and Brits buy whole villages for vacation homes and Africans, Latin Americans, and Chinese workers come in to build them or sell them tourist trinkets. Their children grow up as Mallorquín-Spaniards and change the definition of what that means in a nation that has been trying to understand itself for centuries. Older people who lived through Franco and only spoke their local language behind closed doors now wonder why in the wake of the economic crisis, the immigrants can’t just go home.

True, all these stories could be repeated anywhere in the world, but this is how this one director chooses to express himself in this contemporary globalized context. He frames this expression using some of the same techniques that White Americans developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to deal with their fears of cultural domination by the newly freed African descended Americans. Perhaps the film isn’t that racist, and it may not matter that it takes place in Mallorca, but it takes place in Mallorca. If it was made in say… San Francisco’s “drug-ridden” Tenderloin neighborhood, I imagine it would have come out different?

File Under No Comment: ‘Send Me To Africa’

With a click of the button… (a contest sponsored by sponsors). It’s an empty landscape. With pyramids.

Send Me To Africa

The Farafina Creative Writing Workshop

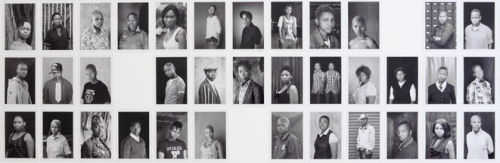

(Photo by Okey Adichie) Participants from left to right: Mona Zutshi Opubor, Senan Murray, Kechi Nomu, Francesca Onomarie Uriri, Richard Ali, Mazi Chiagozie F Nwonwu, Abdulaziz Abdulaziz, Nana Sekyiamah, Monique Kwachou, Gbenga Awomodu, Yewande Omotoso, Chika Oduah, Ese Lerato Emuwa, Yemisi Ogbe, Efembe Eke, Nasir Yammama, Samuel Kolawole, Martin Chinagorom, Kanife Kanamuo Machienti (not included in the photo: Namdi Awa-Kalu).

Guest Post by Yewande Omotoso

If someone told me when I was five or fifteen that at thirty-two I would sit in an air-conditioned room in Lagos, on Victoria Island, with a woman named Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and twenty other writers and I would sit for nine days and we would all talk about writing, our own writing and the writing of others, that there would grow a soft place inside me for all the participants and organisers of this strange meeting, that the meeting would come to an end but actually that things like this never end. If someone had tried to convince me of this it would all have sounded rather unlikely. I guess when I was five Chimamanda wasn’t yet Chimamanda the acclaimed author and Farafina did not have a workshop in its name; there was no Farafina, not yet.

Today I am grateful to have my own memories of what it was like to participate in the 2012 Farafina Creative Writer’s Workshop. And I struggle to write about it without using words like joy, profound, indelible. What struck me about the workshop and the manner in which Chimamanda led it was the intimacy she managed to create with us twenty-one strangers. The workshop days, eight-hour sessions, happened with plenty of humour, lengthy exchanges on the politics of writing, ethics, and what exactly is feminism. We were often asked to write true stories from our life experiences and then read them out to the class. In discussing our histories, our cultures, our prejudices and stereotypes there was sometimes offence taken. This brought with it many apologies, working through misunderstandings and always a burgeoning friendship.

There had been nine hundred applications to the workshop. Chimamanda took pains to explain how the selections were made, no one’s cousin made it through and there was no pandering to calls from big ogas who wanted their sons and daughters to be accepted.

On the first day, as each participant was invited to introduce themselves, I recall thinking I’ll never remember everyone’s name and by the end of the workshop it was as if I had twenty new siblings, the ones who wanted to party, the ones who longed for more pepper in their food and better suya, the quiet ones, the ones who could say one line and have the entire room laughing, the quirks, the annoying habits, the endearing ones.

Accompanying Chimamanda was a taskforce of talented writers and teachers: Aslak Sira Myhre (non-fiction writer and politician, head of Norway’s ‘House of Literature’), Binyavanga Wainana (winner of 2007 Caine Writer’s Prize, author of memoir ‘One Day I Will Write About This Place’), Jeffrey Allen (recipient of the 2002 Whiting Writers’ Award, creative writing teacher and poet) and Rob Spillman (writer and editor of award winning literary journal ‘Tin House’).

To provide an alternative to the continued telling of Africa’s histories, cultures and stories from the perspective of non-Africans, emphasis was placed on non-fiction writing; it’s time (it has always been time) that we tell our own stories. I have always been wary of non-fiction, nervous of mining stories from real people’s lives. Because of this concern I welcomed Aslak’s lecture on ethics and how to write cognisant of the fact that you provide “a” perspective versus “the” perspective. One of the most empowering statements was that sometimes “writing is about the willingness to offend”.

Towards the end of the workshop we were asked to make a list of three of our flaws. Going round the table and having each person (including the teacher) share their list meant, in some ways, we, in that room, were closer to one another than some family members ever get. This would start to fulfil on one of the objectives of the workshop – to create a community of writers that sustains itself beyond the days of the workshop. The visits from alumni proved the success of this with past groups. But it seemed the main reason behind an exercise such as this was to emphasise the very nature of what it is to write. To look and to look honestly. Over the course of the workshop the recurring theme from all the teachers echoed the saying of writer Abraham Rothberg: fiction is a lie that tells the truth. It’s a strange task the fiction writer has, to make something up, invent it, but do it in such a way that the reader forgets they’re reading. And the reason the reader forgets they are reading is because they experience authenticity, there is no story, there is just how things are. As a writer apparently what it takes to create a piece of work that accomplishes that is many hours, many years of crafting, a lot of thinking, plenty of reading and the camaraderie of other writers.

Sentences. The importance of that first sentence when you think of an editor reading your submission (one of two hundred from an initial twenty-thousand) cannot be overstressed! We looked at word-choice and Chimamanda famously said: never purchase when you can buy. It is true that writers (at their own peril) fall in love with big words, get caught up in showing off and forget to just tell a good story. Jeff Allen spoke about how the best fiction is about more than one thing and how fiction is about struggle and conflict. The beauty of simplicity was stressed and we were invited, by Binyavanga, to practice stripping our sentences down to their bare essence – nouns and verbs, naming and doing!

We were given daily readings to discuss and dissect. Why do some stories stay with us and others not? Detail was stressed versus abstract. The character needs to be at risk, have something at stake – why else would we read on if there wasn’t something threatened, a reason to turn the page. Rob Spillman quoted Kurt Vonnegut as saying: every character needs something even if it’s just a glass of water.

I left the workshop shaken. Not in a good or bad way. Just shaken, shocked by the new people in my life. I felt uncertain, I’d arrived with lots of uncertainties but I’d collected a few new ones. “Uncertainty is good” we were told. That will keep you writing, keep you looking. As often happens to me when I experience something I think is special, a sense of melancholy pervaded my last few days in Lagos. Avoiding the inevitable goodbyes, hoping the new people I care for stay well, do well and keep connected; a sense of how precious life is, how sad things can be, how love can turn and not come back to what you remember. I was very afraid and excited. Afraid, as always, of being a terrible writer, of failing. Excited to try. Renewed in my belief, echoed by almost everyone I met at the workshop, in writing as an act of faith. Even an ancient form of prayer.

* Yewande Omotoso is the author of Bom Boy. She lives and works in Johannesburg. Dylan Valley reviewed her debut novel here.

September 10, 2012

My favorite photographs N°5: Abraham Oghobase

Born in Lagos, photographer and artist Abraham Oghobase still lives in the Nigerian metropolis. His work has been exhibited in his home country, the UK, France, Finland and has traveled elsewhere as part of the Bamako Photography Encounters Exhibition. Asked about his own “favorite photographs”, he sent through these five portraits and explains what brought him to make them:

Untitled

I recently moved to a new area in Lagos called Ajah, an extension of the Lekki peninsula which, not that long ago, was a scantily populated ‘border town’ on the outskirts of Lagos but is fast becoming one of the many commercial and residential hubs of the city. One day as I was driving close to home I noticed and was drawn to the particular stretch of wall advertisements (a common sight in other highly populated areas of Lagos) that inspired me to feature them in a series of self portraits capturing my almost daily interaction with this particular aspect of the Lagos environment.

Lagos, the commercial capital of the country, is a city of over 10 million people where competition for space is a daily struggle and extends from accommodation to advertising (and everything in between). As such, every available space, from signboards to the sides of buildings, are indiscriminately plastered with hundreds of handbills and posters and scrawled with text advertising the many and diverse services offered by the city’s enterprising residents and drivers of a robust large informal economy. Validating the authenticity of the information contained in these ads becomes quite a complex task for the consumer, however, due to the disorganized mode of presentation and often incomplete details. My engagement with one such wall of ‘classifieds’ [above] serves to question the effectiveness of such guerilla marketing.

Lost in Transit

This series captures my time spent on a short language course in Berlin, in a city and country so different from my home. It was a confusing, anxious and lonely period as I was also going through other personal transitions at the time; it was also the first time I turned the camera on myself.

With Lost in Transit I explore the challenging process of finding my place in an alien environment. The mind is a function of thoughts and emotions – loneliness, hope, anxiety, enthusiasm. These feelings are revealed in my sojourn in a foreign land as I subconsciously plug into the social and cultural system, yet confused in my quest to find my place in the landscape of the city, Berlin.

In Padua

This body of work was inspired by my experience as a visitor in Padua, an economic hub in northern Italy. Of Padua’s population of 212,500, approximately 3% are African immigrants, who are generally regarded in a negative light due to a recent scarcity of jobs that has forced many migrant labourers to beg on the city’s streets. As a visiting artist in Padua in the summer of 2010, I was struck by a similar, distorted perception of me arising from the colour of my skin, my accent or perhaps my obvious unfamiliarity with a new city and country.

By creating self portraits in spherical street mirrors around the city, I explore a sense of two-way distortions – my outsider’s view of Padua and in turn, the city’s reflection of my (perceived) identity – often very small in relation to the landscape. At the same time, the mirrors allow for greater visibility, extending one’s vision beyond the immediate vicinity – perhaps reflective of my desire for a “bigger picture” view of the obviously more complex people we all are.

Päätön (headless)

I was in Helsinki, Finland in 2011 for a residency supported by the KIASMA Museum of Contemporary Art, and also took part in the ARS 11 exhibition of contemporary African artists. I stayed on an historic Island called Suomenlinna, a sea fortress that is a ferry ride away from the Helsinki. I was there in April, which was still the middle (!) of winter there, and was struck by the reality of how people on the Island live, while also trying to adapt to the harsh climate myself. I naturally continued my exploration of self in yet another ‘alien’ environment.

This work explores the human body in an alien environment – in this case, a wintry landscape void of other human beings. There is a choreographed assimilation of the body and other masses in that space. Here the body takes the form of a headless being to imply its invisibility while validating its presence by taking an ‘alien’ form itself in the environment.

Ecstatic

This series began as an experiment about using my body in relation to space, and juxtaposes the body form and the idea of freedom / self expression with a chaotic / restrictive environment. It’s an ongoing series that I am photographing in different neighbourhoods and landscapes of Lagos (and other cities).

How does one exhale in a demanding and constrictive city where millions of people struggle not just for physical space but also a mental anchor point? When one decides to climb higher than where one is expected to be, then suddenly realizes what is promised doesn’t even exist in that space at the top, do you remain there or jump? When one decides to jump, in an ecstatic moment of escape and temporary liberation, where does he expect to land?

These and many other questions overwhelmed me when I first started this series, Ecstatic. In performing and photographing Ecstatic, I make my way to the top of vehicles around my neighborhood in Lagos only to take a rapturous leap, in effect creating a temporary social space for myself before gravity returns me to reality. This unique space forming as my body curves through the air allows me to agonize, scream, exhale and at the same time empathize with other Lagosians like me in the daily struggle to exist. The inner turmoil created by a merciless city whose pressures tug at me from every side needs some form of exorcism, and Ecstatic has provided me that momentary exhilaration.

These images are all excerpts from larger bodies of work, which can be viewed on Oghobase’s website.

September 7, 2012

Friday Bonus Music Break

Rounding up some music videos we’ve been tweeting over the past weeks, this is your Friday Music Break. Produced by the hardest working rapper in Kinshasa, Lexxus (that’s him in the video, scouting for new talent in Kinshasa’s streets), ‘Bo tia K’ is the first outtake from Bawuta Kin’s upcoming album Ba Wu. Great video too. Above. Next, smooth Kenyan rap from Muthoni The Drummer Queen in ‘Feelin’ it’:

London duo The Busy Twist recorded this music video in Accra:

‘Bravo Papa’ (now with English subtitles) makes us look forward to South African artist Jaak’s Galant album:

Aline Frazão plays an accoustic version of ‘Cacimbo’ (that’s Angola’s dry season):

After a long hiatus, South African TKZee artist Tokollo Tshabalala “Magesh” has recorded new kwaito tunes:

Gorgeous Sudanese a capella by Alsarah and her sister Nahid:

I haven’t counted the times ‘Africa’ gets mentioned in this mishmash video for Madlib’s ‘Hunting Theme’ and ‘Yafeu’ (both taken off his 3rd Medicine Show), but it’s a lot.

Maryland’s Kendall Elijah belatedly got a video out for his track ‘The Wild’ (from last year):

And finally, Donal Scannell created this music video for Sahrawi singer Aziza Brahim’s ‘The Earth Sheds Tears’ in which she remembers those who fought to liberate those parts of the Western Sahara which remain outside of Moroccan control. Aziza Brahim resides in Spain these days:

Zanele Muholi’s “Mo(u)rning” | Exhibition

On Thursday, July 26, the Michael Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town had an opening: Mo(u)rning. Photographic and other works by Zanele Muholi. Muholi had lost much of her work a couple months earlier in a more than suspicious burglary, and so the exhibition was a meditation on mourning, the processes of receiving and releasing the dead and the lost, and morning, the processes of a new day, of another new day. Those who know Muholi’s work will not be surprised to hear the exhibition was brilliant. Rooms upon rooms of portraiture, of lived experience, of love. Video installation merged with photography merged with graffiti and poetry. One wall held, or exposed, Makhosazana Xaba’s poem, “For Eudy”:

For Eudy

I mentioned her name the other day

but blank stares returned my gaze

while all I could see was:

The open field in Tornado

Open hatred on the field.

I thought I could explain

but the rising anger blocked my throat

cause all I was thinking was:

This tornado of crimes

is not coming to an end.

Did anyone read a manifesto

that has plans to stop hate crimes?

Which party can we trust to bring

this tornado of crimes to an end,

an end we’ve been demanding?

How should we pen that cross

and put the paper in its place

while we remember painfully

that the open field in Tornado

is forever marked by her blood?

Name me one politician

who can stand up and talk

about the urgency to stop these crimes,

one who can be counted, to call them

what they are. Name me one.

Go, celebrate Freedom Day,

while we gather and stand

on this open field in Tornado

shouting for the world to hear:

Crimes of hatred must stop!

The next wall had the following scrawl:

Somber? Grim? Hopeless?

No. The night of the opening, the space among the pictures, the testimonies, and the videos was a space of celebration, of hugs and winks and laughter and more hugs, a space of joy. When the communities of local Black lesbians and their friends came together, the event created the joyous space. It was an opening. For one night, in South Africa, the work of mourning is the work of morning.

Dutch author: ‘If only Africans would complain a bit more’

In a recent interview, Pepijn Vloemans, a regular commentator in Dutch mainstream press and the author of the book ‘Wat hebben we weer genoten’ (What a joy we had), described how his drive for adventure and experimental urge to test himself in a low-comfort environment led him to Africa. We’ve lifted and translated some highlights from the interview:

In a recent interview, Pepijn Vloemans, a regular commentator in Dutch mainstream press and the author of the book ‘Wat hebben we weer genoten’ (What a joy we had), described how his drive for adventure and experimental urge to test himself in a low-comfort environment led him to Africa. We’ve lifted and translated some highlights from the interview:

Vloemans: In the Netherlands I lead my comfortable life, while so many things are going on in the world, of which I have no knowledge at all. I thought to myself: “What am I still doing here? I need to leave!” My goal was to test myself in a less comfortable environment. Without thinking I booked a trip to one of the unsafest places in the world. Only roughly did I outline my route. I wanted to travel up along the Nile, through Uganda, to continue to South Sudan, which had just become independent. I had not read a Lonely Planet in advance. I decided to simply go.

Interviewer: You are not particularly advertising Africa in your book.

Vloemans: I intentionally didn’t romanticize the story and left out the beautiful sunsets. Reading about how merry the life of Africans is annoys me, which is why I wanted to show its shadow side. The people over there don’t complain about their situation and as a consequence there is no progress. My book is a praise to the chagrin. [The Dutch' never-ending] complaints about delayed trains might be bad, but it does lead to improvement. In Africa buses only leave when they are full. Apparently no one minds to be late.

Next to the absence of outrage, the short term thinking of many Africans surprised me. I felt I was constantly living in some student digs. For every problem, they seek a ‘houtje touwtje’ [ad hoc] solution. Is the bus door broken? Well, let’s go without it then. It scared me how many people only look one day ahead. I saw the value in the long-term solutions as we have them in Holland, such as old age pensions and hospitals… It almost feels naughty to write something negative about Africa, but the progress that needs to take place is so fundamental that I wondered what development cooperation could contribute. Politically, I became more right wing.

The interview then drifts off into how Vloemans discovers he actually needs his comfort and envies anthropologists, whose energy and interests leads them to indulge into different cultures, before getting back to familiar subjects:

Interviewer: Despite diarrhea, visa stress, unbearable heat and pests, did you also have good times?

Vloemans: Definitely, at certain moments. The city of Gondar was a paradise to me after my journey through the dessert. And the city of Addis Abeba, high up in the Ethiopian mountains surprised me with its fresh air, fresh espressos and Eucalyptus scents. But after those rough weeks I especially enjoyed coming back home to our wealthy country, where everything is well managed.

The book comes with a blurb by much-praised author and much-invited post-colony expert Adriaan van Dis: “Pepijn Vloemans is a true Africa traveller: a man who explores the abysses and the heart of darkness.”

To ensure a minimum of lost-in-translation-damage, we have sent Pepijn an email. He has not yet responded.

Shameless self-promotion. Ghanaian film posters and film viewing culture

Axe of Vengeance: Ghanaian Film Posters and Film Viewing Culture opened last week in Bloomington, Indiana. This exhibit features hand-painted Ghanaian film posters made by Ghanaian artists in the late 1980s to mid-1990s advertising Hollywood, Kung Fu, Bollywood, Nollywood, and Ghanaian films. This was commercial art for urban film houses and theaters that consisted of a television, a VCR, and a gas generator that traveled from town to town in a latter day mobile cinema. The posters were painted with oil and acrylic paints on large flour sacks and traveled too. Young boys often carried the posters around with a bell and announced the evening’s show (according to IU African Studies Program director, Samuel Obeng, who spoke at the opening) offering an auditory component to the already compelling visual one. But as VCRs and TVs became more affordable to the average consumer, the theatres and poster painting associated with them disappeared.

I first saw this exhibit in Chicago where it was called Movie Mojo and the owner of the Chicago gallery that holds this collection, Glen Joffe, is preparing a book by the same title. There are other collections and a similar exhibit ran in Munich, Germany:

If you know these posters you may have seen Ernie Wolfe’s out of print book Extreme Canvas that also documents the phenomenon.

The posters are tied to the Ghanaian and Nollywood film industries that emerged in the late 1980s. Akin Adesokan, Carmela Garritano and Jonathan Haynes have done pioneering academic work on these industries so check them out to learn what the intersection of the IMF, new technologies, economic crisis, novel aesthetics, and entrepreneurial innovation in tough times meant for West African film practice. As Garritano points out, these videos, at least initially, pitted the new aesthetics of economically squeezed urban masses against the conservative, authenticist standards of a dispossessed, nationalist intelligentsia. Birgit Meyer points to the ways that Pentecostal religion’s emphasis on the visual facilitates its adoption of video film media. I think the posters have a static force that amplifies this effect.

While I once wondered — and there was some professorial grumbling about this at the exhibit opening — whether these posters feed negative stereotypes of the continent, I actually think just the opposite. As Glen Joffe put it in his gallery talk, these posters “win the war of engagement.” They are compelling as pieces of advertising cum art and as pieces of popular culture. They draw people in who might otherwise not ever have been interested or imagined that Africans watch B-flicks and Kung Fu movies like young Americans do. And hopefully they will get people to ask more questions about Ghanaian visual artists, Ghanaian film, and history and media. If comments on blog sites that show the posters are any evidence, some folks are now looking at Ghanaian and Nigerian films thanks to the poster paintings.

* This post falls under the category of Shameless Self-Promotion since Betsy Stirratt, Director of the Grunwald Gallery, Jeremy Sweet, associate Director of the Grunwald, and I brought this to Indiana University under the rubric of the 2012 Themester – Good Behavior, Bad Behavior. With many thanks to Nathan Donnelly for his photos of the exhibit opening.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers