Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 524

September 6, 2012

10 African films to watch out for

This is a random selection of ten films we don’t know much about, yet, but which we hope to see once completed or screened at the nearest film festival. ‘The Door of No Return’ (La Puerta de No Retorno) follows Santiago Zannou who accompanies his father, Alphonse, to his homeland, Benin, 40 years after he left it. Trailer above.

‘Finding Mercy’ (which premieres at the Tri Continental Film Festival in Johannesburg this month) is about retrieving a childhood friendship in a newly independent Zimbabwe:

‘Meanwhile in Mamelodi’ is a documentary by Benjamin Kahlmeyer on life in a Pretoria township during the 2010 World Cup:

‘Healers’, directed by Thomas Barry, highlights the work of The Umthombo Youth Development Foundation and tells the story of how a doctor and a matron at a rural South African hospital in KwaZulu Natal started a groundbreaking scholarship programme to enable local youth to qualify as healthcare professionals:

‘Gardens of my Ancestors’ is a short film by South African filmmaker Tsholofelo Monare:

‘After The Battle’ is an account of two people caught up in the Egyptian revolution:

‘Fidaï’ tells the story of an ex-fighter for Algerian independence, and has had its first screening at some recent film festivals:

‘The Hidden Smile’, a short film by Ventura Durall, set in the streets of Addis Abeba:

‘Walking at Dawn’ is a film by Silvia Firmino, set in Mozambique and premiering at the Dockanema Documentary Film Festival in Maputo this month:

And the trailer for ‘The Marshal of Finland’ had a few people up in arms in Finland. True, having a Kenyan actor to play the country’s most famous military figure is quite the coup.

The Vershtunkende Toronto Zoo

The sprawling Toronto Zoo clearly never heard about the controversy surrounding the German Augsburg Zoo’s experience of setting up an “African village” in the summer of 2005. If they had, perhaps they would’ve been more circumspect before hosting one of their own.

The Toronto Zoo is like a North American suburb for animals. It’s sprawling and charmless with domesticated inhabitants either at peace with their lot or chomping at the bit to flee its confines. There are many reasons to stay away from zoos according to those who promote the rights of animals. I have a fair reason for going – an outdoor activity for the kid even in the dead of winter. And my good reason is that the right-wing Toronto mayor is eager to slash its subsidies along with pretty much everything else the city supports beside private property and policing it. (I was about to call Rob Ford moronic or idiotic or cerebrally challenged, but in deriding his capacity for thoughtfulness, we mask his politics, his ideology, normalize it as the stuff of white male suburbanness. It might be normalized. But it needn’t be normal. Public space is under attack under the weight of his austerity drive. And the push-back should be more determined and considered than fixating on his stupidity.)

So, we go to the zoo. It was a steaming hot day in this stereotypically frigid place. And in this zoo, this place where animals are displayed for urban dwellers and other humans who don’t encounter nature much anymore, in this zoo, in its Africa section, we happened upon an African marketplace. Between the slumbering rhinos and the ferocious meatball eating cheetah was a stall selling African curios and fabrics. I have been bothered in the past by the little hut that is usually there denoting a ubiquitous African living space, at one with nature. The kid and I have giggled that the zoo people have clearly never been to say, Windhoek (where even Angelina and Brad have been) because then they’d have to have other types of African buildings too, like houses, and apartment blocks, churches and shacks. But maybe those are associated with a modernity that doesn’t belong on the continent of huts and naturalness. Of course the zoo is a place of commerce and money-making. There are shops near the entrance that sell over-priced stuffed toy animals and other mementoes from the day at the zoo to over-indulged kiddies from over-wrought caregivers. But these are spaces clearly demarcated from the great outdoors by their air-conditioned environs and their location at the zoo’s entrance/exit. There is also no cultural spectacle attached to the consumptive imperative of the Zoo shop. Not so much with the African curios. Curious indeed.

The Toronto Zoo, apparently ‘back’ by virtue of ‘popular demand’, saw fit to host an ‘African Arts and Culture Festival’ from June 30 to September 3 2012. On its website, the zoo promises that “[t]raditional and contemporary artists will transform the African Savannah landscape of the Zoo into an interactive Market Place for our visitors to learn and engage in the African experience.” Considering the context and some of the signage, the lessons learned by visitors would be to associate Africa and Africans with wild and untamed nature, with cultural production deeply rooted in their feral habitat. The Augsburg Zoo’s African Festival was met with outrage; Toronto’s with apparent enthusiasm. No doubt this is also a contextual response. German history has come to demand increased appreciation of the ways in which stereotyping can participate in producing justifications for grotesque human acts (although guest workers and their descendants may not believe that). Toronto, on the other hand, regards itself as a multicultural fantasy-land.

While the idea of multiculturalism can force us to think of opportunities for change and dynamism as we figure out new ways of being conscious and living together, it all too often permits us to lazily inhabit the realms of stasis. What I mean by this is that ‘culture’ often stands in for the more antiquated, discredited and odious pre-occupation with biology. Culture is understood to be as genetically determinant as race once was. It operates in a similar way to racism; although of course theoretically we can immerse ourselves in ‘different’ cultures and adopt them. This is still limited though by the cultural heritage that runs through our veins, like blood: the schnorrer Jew by virtue of culture, of generations of miserliness, not of genetic codes; or the philandering black man by virtue of tradition that has become nature rather than omnipotently ordained proclivity. It is not racist per se. But we could consider it to be neo-racist.

In case it’s not offensive enough to display the products of hard labour aside the scent of elephant shit, the Toronto zoo in its wisdom had a collection of Southern African art on display too. The display was beautiful, shaded by willows, whose weeping was perhaps for the association of this artwork with a vershtunkende zoo.* Not far from there is a permanent display of Inuit and First Nations art. Seems the place for indigenous talent, like its African counterpart, is in the zoo. And there we thought the final word on noble savagery could be given to Joseph Conrad.

Recently, the Toronto Zoo imported penguins from Cape Town. There was a bit of a brouhaha when they arrived as two of the male penguins shacked up… but heteronormativity and the pre-occupation with breeding in penguin-land has subsequently been re-established. This summer, two white lions from Timbavati joined the other creatures from the African Savanna in Toronto. The African elephants have been all over the news these past few months as a battle ensues as to where best they should retire (stay in Toronto or head to California). And into this growing family of African animals, come the humans, their crafts and their music. Call me sensitive, but given the history of denigration of the African continent and the people who live there, a zoo seems a particularly inappropriate space for the promotion of African arts and culture.

On a separate but equally offensive note, the kid and I also went to see the exciting “Giants of Gondwana” exhibit at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). Neither of us knew though just how old Africans are. We were gratefully enlightened by the ROM store that had its dinosaur wares on sale decorated by African masks and carvings. Gondwana, the supercontinent of the South, was home to some of pre-history’s largest creatures like Tyrannosaurus Rex. They were wiped out during the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event some 65 and a half million years ago. According to the museum store display, transporting African crafts back millions of years is an acceptable articulation of Africans outside of time, outside of history.

* “vershtunkende” is a Yiddish adjective loosely translated as ‘darned’, ‘exasperating’, ‘maliciously idiotic’. It is not a nice word to use for either a person or thing.

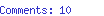

My favorite photographs N°4: Nana Kofi Acquah

My grandmother had a pub where wayfarers, fishermen, their wives, officers and anybody who had trouble or was looking for a little happiness would come, buy tots of the local gin, “akpeteshie” and start pouring their souls out. I would crawl under tables, eaves dropping and soaking it all in. When I got bored listening to them, I’d run to the beach, sleep in a docked canoe, play soccer with my friends, catch crabs or help some fishermen pull in their catch of the day.

Picking up the thread from earlier this year, Ghanaian “storytelling” photographer Nana Kofi Acquah sent through his “5 favorite photographs”, and explains why.

“Impressive but Depressive.” Those three words are stuck in my head and always pop up when I remember my exhibition in Bamako. I was showing The Slaughter Boys — a series on animals slaughtered on the beach in commercial quantities for consumption across Ghana’s capital. Those were the words from one of the viewers and the photograph above is my favourite from that series.

You must remember that I consider myself, first and foremost, a storyteller before a photographer. I love people and the stories they have to tell. When you take photos for a living, there’s always the temptation to treat assignments as just assignments but if I worked like that, my love for photography will die in no time. I need to always connect. Feel. Explore. Discover. Disrupt. Observe. Challenge. I made this quiet photograph of a woman harvesting maize on a very busy farm; in a hyper-charged atmosphere of laughter and celebration. Harvest is always a good time for farmers. It took a lot of effort to not get carried away, to get something simple and beautiful. I am happy to say this photograph graces the cover of a just released coffee table book.

I’ve been working on a series called ‘Bedroom Portraits’. I’ve been looking at Accra, its people and where they sleep. In the pursuit of this story, I have photographed folk who sleep in cemeteries and those who live in mansions. One of my favourites from this set is of James. James hasn’t slept on his bed in eight years. He’s a self-employed IT guy and has a few companies that hire him as auditor.

On this particular assignment, I also got to photograph the two Liberian women who, not long afterwards, won the Nobel Peace Prize but it’s not their photographs I’m sharing with you. This girl is a seamstress’ apprentice. Trying to pick up life from where the war left it. I don’t know what her experiences were but the sticker on her sewing machine spoke volumes.

This last photograph is from Elmina, where my umbilical cord is buried. Elmina is my love and pain. I was born about 200 metres from where that slave castle stands but I never went in there as a child. My mother has never been in there. Most people from Elmina never go in there because it’s depressive. So imagine me walking out of that haunted edifice and then these noisy school girls, just walk past me shouting, laughing out loud in a language I love to speak: Fante. It really was a breath of fresh air and the whisper of hope my soul so needed to hear.

September 5, 2012

Paulo Flores’s Ex-Combatentes

Paulo Flores (Photo via Irina Tatiana de Almeida)

Earlier this summer Paulo Flores launched Ex-Combatentes Redux, a 15 track version of his 3 CD Ex-Combatentes (2009) at the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris and then played at the Rio Loco Festival in Toulouse. If you are an assiduous consumer of Putamayo compilations or of Portuguese language music you may know Flores’s work. Sadly, his music is not distributed or well-known in the U.S., despite the fact that he can never be anonymous on the street in Luanda, no matter the hour of the day.

It is easy to slather him with superlatives as his fans on Facebook and the press do. He deserves all that and more. The more of course would be serious critical attention. The international press – and this was the case for the most part this summer in France – still mostly cast him as a poster boy for post-war Angola even when they give him high praise. Now, the album is titled “Ex-Combatentes” (Ex-Combatants), which happens also to be the name of the street he lives on in Luanda, but the music in sound and lyrics has little to do with war. Unless one thinks of war in the widest sense – war with the self, war with family, neighbors, friends, etc. Like in the blues tune on Ex-Combatentes, ‘Eu quero é paz’, written with Albano Cardoso. Perhaps what Flores does most brilliantly is to capture Angola’s humanity, at its extremes and in its intimacies; the war on all fronts, the small peaces made every day.

The 3 CD version of Ex-Combatentes celebrates twenty years of work as a musician (Flores started playing professionally at the age of 16) and includes a tremendous diversity of styles and collaborations with Mayra Andrade (Cape Verde), Manecas Costa (Guinea Bissau) and Jacques Morelenbaum (Brazil), among others. On earlier CDs, like Recompasso, Flores has collaborated with Sara Tavares and Tito Paris and he always works with a diverse set of Angolan artists including Eduardo Paim, Yuri da Cunha, Carlos Burity, Banda Maravilha, Teddy Nsingui, Pirika Duia and others. He’s been reinvigorating semba, the Angolan music of the 1960s and ’70s that was eclipsed by other forms and forces by the late 20th century — so old Angolan tunes are riffed, re-worked, and re-imagined on these CDs too.

The 3 CD version of Ex-Combatentes celebrates twenty years of work as a musician (Flores started playing professionally at the age of 16) and includes a tremendous diversity of styles and collaborations with Mayra Andrade (Cape Verde), Manecas Costa (Guinea Bissau) and Jacques Morelenbaum (Brazil), among others. On earlier CDs, like Recompasso, Flores has collaborated with Sara Tavares and Tito Paris and he always works with a diverse set of Angolan artists including Eduardo Paim, Yuri da Cunha, Carlos Burity, Banda Maravilha, Teddy Nsingui, Pirika Duia and others. He’s been reinvigorating semba, the Angolan music of the 1960s and ’70s that was eclipsed by other forms and forces by the late 20th century — so old Angolan tunes are riffed, re-worked, and re-imagined on these CDs too.

The 3 CDs are titled Viagem (Journey), Sembas, and Ilhas (Islands) and here’s a sample from each below but you should really seek out the full Ex-Combatentes if you can because it is a very complex and rich set of music. If you understand Portuguese you will have the double pleasure of Flores’s poetry and clever lyrics, which both charm and, I sometimes think, elude his fans.

If you want to hear more of this music you might check out the excellent Caipirinha Lounge blog where it was reviewed in 2010.

And pay attention. Paulo Flores has spent most of the summer in the studio recording a new album. We promise to keep you posted.

‘Pé na Lama.’ This video is by the artist Nastio Mosquito, whose work we’ve mentioned before:

‘Rumba Nza Tukiné,’ a tune by David Zé who died an untimely death in 1977. Here’s an acoustic version at Luanda’s Teatro Elinga, recently de-classified as historic patrimony so that a skyscraper can be built (but we’ll save that for another post).

‘Amba,’ also an older song by Murimba Show. The video was shot by Sergio Afonso in the Namibe desert in Southern Angola and at Miradoura da Lua, outside Luanda. Here a song from the late colonial period is used as a critique of poco society: the new man sees no evil, hears no evil…

While we were tweeting…

The month of August came and went explosively in South Africa, with 34 striking miners killed in a hail of police bullets. Ten more have died in the protracted strike (2 police, 2 security guards, and an additional 6 mineworkers).

While the Africa is a Country collective was officially on vacation, we tweeted extensively about the Marikana Massacre, and published some analysis in traditional media. Sean Jacobs and contributor Daniel Magaziner argued in ‘The End of South African Exceptionalism’ (in The Atlantic Magazine) that

the lessons [of Marikana] are not so much about fulfilling the promise of post-apartheid as they are the less particular but even more daunting challenges of poverty and inequality, those faced by the entire international community… Rather than judge South Africa in the wake of this 21st century Sharpeville, the rest of the world ought to ask what kind of community post-apartheid South Africa has joined.

AIAC contributor, Jonathan Faull, reflected on the uncanny coincidence of the ongoing Lonmin strike with the 25th anniversary of the 1987 National Union of Mineworkers strike, in ‘A World Upside Down’ (in the Mail & Guardian):

the killing at Marikana must serve as a catalyst for re-examining what constitutes “leadership” in South Africa’s business community, and the relationships between elites forged so quickly in the name of “transforming” South Africa’s economy.

Also engaging with South Africa’s past, Lily Saint published an article in Social Dynamics on “Reading subjects: passbooks, literature and apartheid”, in which she argues that

despite passbooks’ unparalleled control over South Africans’ everyday lives [under Apartheid], passbooks failed to mould all life stories into the rigid forms promulgated by apartheid doxa. Counter-narratives in black and ‘coloured’ writing of the period provide a useful framework for re-evaluating the role of reading and writing in the production of power. As interventions in the apartheid state’s monopoly of public discourse, such writing insisted that there be alternative ways of writing the apartheid subject into the archive. (Full article.)

And in response to Elliot Ross’s rejoinder to the Fund for Peace and Foreign Policy’s Failed States Index, Elliot was invited to debate “Who Decides When States Fail?” on Al Jazeera’s The Stream:

Our collective thoughts and condolences go out to the families of all the 44 dead at Marikana. A tragic, and entirely avoidable, chain of events.

Makoko: This sea shall be uprooted

Guest post by Jumoke Verissimo. Images by Adolphus Opara

I

Dreams brought us here and we arrived

With no enthusiasm for things stirring

– Currents, currencies – concurrently drift us

Into adamance, but we learnt before to be.

Lagos: the Nigerian coastal city is shriveled up by growing population; each new government seeks newer ways to expand the territory. The current governor started by clearing illegal structures and refuse dumps. It is difficult to believe that there was a time when Lagos was largely a scenery of garbage heaped so high that some mistook it for mountains waiting for climbers. Before long, many inhabitants of the city welcomed the initiation of “a new Lagos”, where the streets are cleaner, and cleaners in uniform sweep away dirt at intervals—a city which deserves the tagline: City of Excellence. Lagos is still not too clean, yet the ‘visible’ change and immersive Public Relations of Governor Raji Fashola’s first term in office has helped inhabitants to see the place differently, especially with the I see Lagos adverts. Fashola’s goodwill has been rising, until just recently, when it sunk a few metres below sea level with the demolition of some parts of Makoko, a pile dwelling that has existed for over 200 years.

Two years ago, the BBC shot a documentary, Welcome to Lagos, which generated many debates, and brought more pilgrimages to Makoko than it had ever received in the past. It seemed not to be the type of imagery the state government wanted amid its efforts to attract tourism and investments, and though it took 48 months to issue a 72-hours quit notice to the inhabitants of Makoko in July, it was issued.

Two years ago, the BBC shot a documentary, Welcome to Lagos, which generated many debates, and brought more pilgrimages to Makoko than it had ever received in the past. It seemed not to be the type of imagery the state government wanted amid its efforts to attract tourism and investments, and though it took 48 months to issue a 72-hours quit notice to the inhabitants of Makoko in July, it was issued.

This demolition has generated a wide response, for and against. Support for the destruction of the place is mostly from those who have bought into Fashola’s vision of the New Lagos, while those against are of two types: those who are concerned about the lack of alternate residence, and those who are looking at the cultural ecology and history of Makoko’s people. Sadly, most media descriptions have looked at Makoko—which has over 100, 000 residents—as a shanty. There’s more to it. This is the destruction of a community.

II

After today we shall berth, in a row

Unlike other days our boats floating in semblance

We will haul desires to shores,

Perhaps come back with everywhere on our minds

With power in our loins, we’ll find repose in luck.

Driving across the bridge, on Third Mainland, one would see the rows of boxes, lumbers floating on the waters and sometimes fishermen in their canoes slipping past. While the scenery can be beautiful as the sun sets, the area still does not represent the ideal home for many Lagosians because it is figured as a place for a particular people—the Ilaje, the Ijebu, the Egun, who history favours as those who live close to water. The government has remained obstinate about its position on demolition, saying that the people should place their trust in government, “rather than any other person”, and that the demolition is best for them, as it will protect them from those who extort money on their behalf. There appears to be something personal about Governor Fashola’s accusation. Who are those extorting money from the residents of Makoko?

Even if the governor has this knowledge, he is more comfortable with knowing the settlement as a hideout for immigrants arrived from Cameroon, Benin and Togo without papers, which would be an argument against city districts anywhere across the world. But Makoko comes with a different story. It is interesting that over four different languages are spoken in the locale, principally Egun, Ijaw, Ilaje, Yoruba, the lingua franca, and some sub-groups. Neighbours may not even speak the same language, yet co-existence is cordial. Some of the inhabitants have never left the waters, so their total life experience is involved in the mundane activities peculiar to the place: fishing, logging, and perhaps television. The only school in Makoko was instituted by an inhabitant who returned to start one.

For an area with a pile-dwelling population that now numbers over a hundred thousand to have lurked for two centuries within a state, is without doubt a significant oversight. The absence of basic infrastructure like schools means it has never been a part of the state in the actual sense. It was just a kind of self-sufficient extra area bordering the city, until foreigners took note of it, and gave it media attention. It may not be wrong to think that the government’s lack of concern over this environment has quickened its degradation, and that is what is being said between the lines: Makoko has been denied infrastructural facilities because it is not official. Preserving the identity of a people is as important as the social amenities, and it appears the government believes the residents of Makoko lack one.

Knowing that the residents of Makoko voted in the last election, it is merely fair that Governor Fashola should use this crisis to create an “official” Lagos which accommodates a more diverse range of conditions, a Lagos that genuinely caters for the varied class structure occupying the state at this time. The diversity of Lagos should be put into the plans of his proclaimed “mega city” architecture, or else the excellence he seeks will become another social-class illusion that is informed by Western values. One major eviction that got as much attention as this was the clearing of Maroko in 1985 by Colonel Raji Rasaki, then governor of the state. Rasaki claimed to have an alternative involving resettlement plans for the inhabitants, but these plans only reached a very few. The court case over the clearance of Maroko is still open against the government.

Raji is again in the news: a Raji Fashola this time, on another destruction assignment and he has chosen a name close to his namesake’s: Makoko!

Jumoke Verissimo is the author of “I am memory”, a book of poetry. She lives in Lagos and blogs at WRITESTUFF.

With many thanks to Adolphus Opara for his photographs of Makoko. We touched on his ‘Shrinking Shorelines’ series in January and his ‘Emissaries of Iconic Religion’ when it was shown at the Tate last year. Just last week he was profiled by the Guardian.

Makoko: This Sea shall be uprooted

Guest post by Jumoke Verissimo. Images by Adolphus Opara

I

Dreams brought us here and we arrived

With no enthusiasm for things stirring

– Currents, currencies – concurrently drift us

Into adamance, but we learnt before to be.

Lagos: the Nigerian coastal city is shriveled up by growing population; each new government seeks newer ways to expand the territory. The current governor started by clearing illegal structures and refuse dumps. It is difficult to believe that there was a time when Lagos was largely a scenery of garbage heaped so high that some mistook it for mountains waiting for climbers. Before long, many inhabitants of the city welcomed the initiation of “a new Lagos”, where the streets are cleaner, and cleaners in uniform sweep away dirt at intervals—a city which deserves the tagline: City of Excellence. Lagos is still not too clean, yet the ‘visible’ change and immersive Public Relations of Governor Raji Fashola’s first term in office has helped inhabitants to see the place differently, especially with the I see Lagos adverts. Fashola’s goodwill has been rising, until just recently, when it sunk a few metres below sea level with the demolition of some parts of Makoko, a pile dwelling that has existed for over 200 years.

Two years ago, the BBC shot a documentary, Welcome to Lagos, which generated many debates, and brought more pilgrimages to Makoko than it had ever received in the past. It seemed not to be the type of imagery the state government wanted amid its efforts to attract tourism and investments, and though it took 48 months to issue a 72-hours quit notice to the inhabitants of Makoko in July, it was issued.

Two years ago, the BBC shot a documentary, Welcome to Lagos, which generated many debates, and brought more pilgrimages to Makoko than it had ever received in the past. It seemed not to be the type of imagery the state government wanted amid its efforts to attract tourism and investments, and though it took 48 months to issue a 72-hours quit notice to the inhabitants of Makoko in July, it was issued.

This demolition has generated a wide response, for and against. Support for the destruction of the place is mostly from those who have bought into Fashola’s vision of the New Lagos, while those against are of two types: those who are concerned about the lack of alternate residence, and those who are looking at the cultural ecology and history of Makoko’s people. Sadly, most media descriptions have looked at Makoko—which has over 100, 000 residents—as a shanty. There’s more to it. This is the destruction of a community.

II

After today we shall berth, in a row

Unlike other days our boats floating in semblance

We will haul desires to shores,

Perhaps come back with everywhere on our minds

With power in our loins, we’ll find repose in luck.

Driving across the bridge, on Third Mainland, one would see the rows of boxes, lumbers floating on the waters and sometimes fishermen in their canoes slipping past. While the scenery can be beautiful as the sun sets, the area still does not represent the ideal home for many Lagosians because it is figured as a place for a particular people—the Ilaje, the Ijebu, the Egun, who history favours as those who live close to water. The government has remained obstinate about its position on demolition, saying that the people should place their trust in government, “rather than any other person”, and that the demolition is best for them, as it will protect them from those who extort money on their behalf. There appears to be something personal about Governor Fashola’s accusation. Who are those extorting money from the residents of Makoko?

Even if the governor has this knowledge, he is more comfortable with knowing the settlement as a hideout for immigrants arrived from Cameroon, Benin and Togo without papers, which would be an argument against city districts anywhere across the world. But Makoko comes with a different story. It is interesting that over four different languages are spoken in the locale, principally Egun, Ijaw, Ilaje, Yoruba, the lingua franca, and some sub-groups. Neighbours may not even speak the same language, yet co-existence is cordial. Some of the inhabitants have never left the waters, so their total life experience is involved in the mundane activities peculiar to the place: fishing, logging, and perhaps television. The only school in Makoko was instituted by an inhabitant who returned to start one.

For an area with a pile-dwelling population that now numbers over a hundred thousand to have lurked for two centuries within a state, is without doubt a significant oversight. The absence of basic infrastructure like schools means it has never been a part of the state in the actual sense. It was just a kind of self-sufficient extra area bordering the city, until foreigners took note of it, and gave it media attention. It may not be wrong to think that the government’s lack of concern over this environment has quickened its degradation, and that is what is being said between the lines: Makoko has been denied infrastructural facilities because it is not official. Preserving the identity of a people is as important as the social amenities, and it appears the government believes the residents of Makoko lack one.

Knowing that the residents of Makoko voted in the last election, it is merely fair that Governor Fashola should use this crisis to create an “official” Lagos which accommodates a more diverse range of conditions, a Lagos that genuinely caters for the varied class structure occupying the state at this time. The diversity of Lagos should be put into the plans of his proclaimed “mega city” architecture, or else the excellence he seeks will become another social-class illusion that is informed by Western values. One major eviction that got as much attention as this was the clearing of Maroko in 1985 by Colonel Raji Rasaki, then governor of the state. Rasaki claimed to have an alternative involving resettlement plans for the inhabitants, but these plans only reached a very few. The court case over the clearance of Maroko is still open against the government.

Raji is again in the news: a Raji Fashola this time, on another destruction assignment and he has chosen a name close to his namesake’s: Makoko!

Jumoke Verissimo is the author of “I am memory”, a book of poetry. She lives in Lagos and blogs at WRITESTUFF.

With many thanks to Adolphus Opara for his photographs of Makoko. We touched on his ‘Shrinking Shorelines’ series in January and his ‘Emissaries of Iconic Religion’ when it was shown at the Tate last year. Just last week he was profiled by the Guardian.

Kaleidoscope goes to Africa

The summer issue of Kaleidoscope, a contemporary art magazine based in Milan, is devoted to ‘art and culture produced in (or related to) the African continent today.’ It’s full of good stuff. Many of the artists we’ve written enthusiastically about in the last twelve months — Santu Mofokeng, Hassan Khan, Rotimi Fani-Kayode — are there, alongside some work we’ve been troubled by and critical of. I am largely ignorant of the provisions for fair use in international copyright law, so here’s a summary of the magazine’s contents, with liberal excerpts of some of the most interesting bits.

The summer issue of Kaleidoscope, a contemporary art magazine based in Milan, is devoted to ‘art and culture produced in (or related to) the African continent today.’ It’s full of good stuff. Many of the artists we’ve written enthusiastically about in the last twelve months — Santu Mofokeng, Hassan Khan, Rotimi Fani-Kayode — are there, alongside some work we’ve been troubled by and critical of. I am largely ignorant of the provisions for fair use in international copyright law, so here’s a summary of the magazine’s contents, with liberal excerpts of some of the most interesting bits.

1. A brief and curious essay on the work of Santu Mofokeng:

His photographing from recalcitrant space outwards likely accounts for the vast difference between Mofokeng’s photography and that of his South African colleague David Goldblatt, who prefers an unbelievably sharp, clear-cut and transparent image.

An interview by Shahira Issa with Hassan Khan and Wael Shawky, both have work in this year’s dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel, Germany. Khan’s film Jewel featured in the New Museum Triennial earlier this year and I thought was great; his work in Kassel is “Blind Ambition” part-film, part-installation — you can see more images of it over at Al-Ahram. Shawky’s work at Kassel — Cabaret Crusades: The Path to Cairo – is a film adaptation of Amin Maalouf’s text, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes (1984). In the Kaleidoscope interview (which can be read for free online) Shawky explains how he used the puppets to create ‘a historical narrative’ which is also a ‘critique of historiography’, and chose to focus on ‘events that are mentioned only briefly in historical references’. You can see images of his terrifying puppets over at Nafas.

2. An illuminating article on Sci-Fi narratives by Nav Haq and Al Cameron, curators of the Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction exhibition which we’ve already written far too much about (here and here and here).

3. A piece on the work of the performance artist Athi-Patra Ruga, ‘Considering its commonalities with hysteria’:

Athi-Patra Ruga is wearing ridiculously high heels. A leotard clings to the artist’s cock, which is circumcised. It is the opening night performance for La Mama Morta (They Killed My Mother) at YoungBlackman, Cape Town in 2010. Inside the white cube, behind glass, the artist is convlusing. He throws himself hard against the gallery walls.

4. Information on the Cinémathèque de Tanger, a non-profit organization which aims to promote cinema culture in Morocco. Words by Bouchra Khalili, one of the co-founders:

It was at Casa Barata, Tangier’s extraordinary flea market, that we fully realized that we were founding a cinémathèque. We were literally picking up Super 8 reels that were older than we were, off the ground, and dreaming about the treasures they might contain.

5. A portfolio of the photographs by Viviane Sassen.

6. An essay by writer and curator Nana Oforiatta-Ayim on her Cultural Encyclopedia project, which featured as a sketch alongside the work of the Invisible Borders collective in the New Museum Triennial. The essay, which can be read online, describes the project’s extraordinary ambitions:

It is these monumental changes that the Cultural Encyclopedia, a massive documentation project that I’m currently involved in, will account for. For now the prism of the nation is still the most comprehensive one we have, even though it might not always be so. The Cultural Encyclopedia will map, in fifty-four volumes, the trajectories of historical and contemporary cultural production on the African continent. It will be headed by a core team based in Africa, but its expression will expand out to thinkers, artists, philosophers and scientists from across the world. It will be printed in book form on a model based on the Bibliothèque Bleue, which was distributed not just among an urban elite, but also amongst the masses, distributed through both the formal and informal networks, at petrol stations, through mobile vendors and markets, as well as on the Internet.

7. Olufemi Terry (see his pieces for this blog here) in conversation with Frances Bodomo, Jean-Pierre Bekolo and Mahen Bonetti. Frances Bodomo has some particularly interesting comments on Pieter Hugo:

Pieter Hugo’s photos are a constant inspiration for my visual idea of Africa, but I struggle with the way many have come to see him as a “voice of Africa.” And I don’t think it’s about losing a sense of wonder. I think if any of his subjects were to make a film or take pictures from their lives we would find in these infinitely more “exotic” things. But they wouldn’t simply be “exotic,” but a refreshing portrayal of human experience – a humanized depiction of Africa, rather than an objectified and/ or exotic one. This is my struggle with Pieter Hugo: he takes uniquely beautiful photographs, but many viewers of these photographs assimilate them into their view of Africa, and make the subjects objects.

See Megan Eardley’s interview with Bodomo on this blog in April here.

8. An essay on music, mainly on the use of pidgin in Ghanaian kuduro, by Benjamin Lebrave, which can be read online here.

9. An essay on urban planning in Africa by Antoni Folkers, especially interesting for its mention of speculative plans by Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez. You can see more images of his models here.

10. A portfolio of photographs by Rotimi Fani-Kayode (whose exhibition in New York we reviewed here).

11. An interview with Nicholas Hlobo, an artist who has been making some extraordinary work with leather, by Sean O’Toole. Hlobo says:

I am curious about who I am, my origins, the migratory origins of black South Africans, and the mosaic qualities of Xhosa rituals. […] I feel I should not rob the viewer of the opportunity to create his or her own understanding of the work. Hence, the titles of my works are not translated, so that whoever is reading the title is made to look at the object. […] People have often said my work is too white, which I find very interesting. My work and my personal life are intertwined; I find it difficult at times to separate myself from my work.

This is literally true of several works pictured in the magazine, in which the artist is either contained by or attached to large leather pouches. The interview is followed by two essays, by Tracy Murinik and Liese van der Watt, the first of which can be read online here.

12. A portfolio of images by Namsa Leuba, from her book Ya Kala Ben, produced in Guinea-Conakry.

13. An interview by curator and art-world-titan Hans Ulrich Obrist with ‘the Afropolitan artist’ (a label not discussed in the interview) Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, whose paintings at the New Museum Triennial I describe with stupidly little detail here. The artist, born in London in 1977, makes some of the most exciting and challenging paintings being exhibited right now. Obrist asks her about the influence of Ghana on her practice, and Yiadom-Boakye emphasises an understatement:

HUO: I would like to ask you about Ghana, as your family comes from there. I was wondering if you have any connections to Ghana or Africa?

LYB: Not very strong ones. I mean, my strongest connection is my parents.

HUO: Who live there?

LYB: NO, they live here in London, and they have for forty years. But just the fact of them having raised me the way that they did, they are my connection. I find of have an idea of Ghana from them, but I wouldn’t say I have a strong personal connection with it, in that I haven’t been there that much and I certainly never lived there. I wasn’t born there – I was born here, and I was raised here. Really my connection is through my relatives, the people who raised me, and their way of thinking, which to me is very Ghanaian, and that has obviously effected how I think and what I think about. But it would be disingenuous of me to claim some strong connection with Ghana as a place because I don’t really know it and I wasn’t raised there.

HUO: But it’s there through the transmissions of your parents.

LYB: Definitely. The way I always put it was that Ghana is present as a way of thinking and a way of seeing, which has influenced me.

The rest of the interview can be read here.

14. ‘Notations from the public diary of Invisible Borders’ by Emmanuel Iduma, a writer documenting on the photography collective’s second annual journey, currently underway, between Nigeria and Ethiopia. The article takes three themes — Safety, Borders, Transportation — to raise the objects and obstacles of travelling through Tchad, Sudan and Ethiopia.

Yes, there are rumors that turn out to be true. But there are rumors that never turn out to be true, rumors that are in fact not true. There are even warnings that are given based on past occurrences, based on the fear that wht happened in the past might reoccur now. The instant challenge when you receive a warning is to understand that an event is not bound to occur, that the future is not the past or the present. The future is yet to happen. So it was with us. We received warnings.

Check the Invisible Borders Facebook page for their updates and photos.

15. A historical study of the 1935 exhibition at MoMA of “African Negro Art” by Paola Nicolin, which makes some incisive points on the curation of contemporary African art:

MoMA’s space was also completely white: an absence of color that seemed like an aesthetic response to the objects. How does the choice of colors and materials in museums today reflect a different – or identical – approach to cultural diversity? It was [Alfred J.] Barr, in line with the MoMA mission, who thought of the exhibition as a crucial tool for the creation of the occidental canon of African art, and grasped the importance of its documentation and the possibility that the exhibition project, once finished, could continue to be used as an educational tool, through its representation.

16. A piece on Massimo Grimaldi, an Italian artist who hijacks art prizes by submitting applications for works of art which involve giving most of the money to medical charities working in Afghanistan, Sudan and Sierra Leone, a gesture one judge apparently described as “moral blackmail”:

I think the intelligence of some of the jurors was to recognize that the moral blackmail was a structural part of the work, just like a painting technique. The lack of scruples, almost the violence of these projects that test the ethical character of an institution and even the moral character of the individual jurors is clear, confronting them with the question: “What is better: to make some art-work or to save human lives?”

In 2009, the artist gained funds from the MAXXI 2per100 award, a competition established by the MAXXI museum, compelled under Italian law to set aside at least 2% of their total budget to the production of art. The artist used 92% of the 700 000 euro prize to build a pediatric hospital in Sudan. Images of the project — Emergency’s Pediatric Center in Port Sudan Supported by MAXXI — were then projected on a wall of the Roman museum.

17. Last, an interview by Carson Chan with Elvira Duangani Ose, recently appointed Curator of International Art at the Tate Modern, a post sponsored by Nigerian Guaranty Trust Bank, who is involved in plans for partnerships with art institutions in Africa (more on that in this interview with the Mail & Guardian). The Kaleidoscope interview, which can be read online here, has lots of interesting points and references. For some reason Chan uses the interview as an opportunity to respond to criticisms (like the one we made here and here) of the Marrakech Biennale, which he co-curated.

Chan tries to persuade Duangani Ose to agree that criticisms of his exhibition by ‘Western critics and observers’ (but also, remember, by the Jamaa collective) aren’t valid. We critics are, apparently, guilty of ‘ideological patronage’ for having suggested that the organisers had failed to make adequate representation of art from the African continent. Duangani Ose eventually answers Chan with the simple statement, “it’s the curator’s choice”. But it’s also about the choice of curator. Chan is clearly an intelligent curator, sensitive to the political implications of these things, and he has done impressive research with which he defends himself against criticism, but this doesn’t change the fact that the Marrakech Biennale is the play-thing of Vanessa Branson, who chose the wrong curators.

*

Elsewhere, Kaleidoscope elegantly negotiates its descriptions of art in the African continent and disapora with the demands of identity politics and universalism. But as the editor, Alessio Ascari writes, ‘this overview is necessarily not exhaustive, partially arbitrary and … to be continued.’ The mapping out of Africa in contemporary art is a mammoth task but it too often excludes many of the same countries. As usual, art from South Africa, Ghana and Nigeria predominates. What about Tunisia? Chkoun Ahna, an exhibition at Carthage Contemporary earlier this year, suggested interesting things are happening there. What about Zimbabwe, Algeria or Tanzania? Exclusions made in these overviews are rarely arbitrary and have much to do with relations between the art market and local economies, the politics of the diaspora, the development of art institutions in Africa.

Any project — Kaleidoscope magazine or this blog — which makes even the most obscure claims to (or extravagant refusals of) representing a region of the world must confront these questions. Third Text journal recently issued a call for papers on contemporary art and ‘Lusophone’ Africa, suggesting that recent interest in contemporary art from the continent has been ‘skewed’ towards countries with larger English-speaking populations. Representations which seek to map out these exclusions, and describe obstacles to the growth of contemporary art culture in the countries frequently ignored in such overviews, would offer a better understanding of the art objects which educate and please Western observers without obscuring the fact that they threaten the whole idea of “an occidental canon of African art” with its necessary and inevitable destruction. Since Ascari has promised that this is ‘to be continued’, we hope their next Africa issue is as strong as this one and can explore art from some of the regions neglected here.

September 4, 2012

Il Manifesto

It may come across as self-indulgent and somewhat presumptuous that I named the original version of Africa is a Country “The Leo Africanus.” But it was also a fortuitous choice for a blog name that helped me initially draw links between the Early Modern “Moorish diplomat,” who similarly reported on the wonders of Africa to his European audiences, and what I wanted to do by maintaining a public diary of my own experiences as an out-of-place African.

If you may recall, Leo Africanus refers to the 16th century writer and traveler about whom “few facts are known,” except “that he was born al-Hasan al-Wazzan, in Granada,” which was known as “the New York of that time” in Islamic Spain (as part of al Maghreb). He moved with his family to Fez, in Morocco, after the Spanish defeated the Islamic rulers there. In Fez, al-Wazzan studied at the famed University of Al Karaouine. As a teenager, he accompanied his uncle who traveled as an envoy of the Sultan of Fez. Al-Wazzan was later employed as a diplomat himself and claimed to have journeyed to Timbuktu and Gao in what was then part of the Songhai Empire, and what is now Mali, Sudan (“the land of the Blacks”), Egypt and Constantinople. Then, in 1518, as he was traveling back to Tunis, he was kidnapped in the Mediterranean by corsairs (“official” pirates) who brought him to Rome. The normal fate of Muslim prisoners was slavery, but al-Wazzan was taken to the papal court where he became a confidant of Pope Leo X. The Pope personally converted and baptized him; from thenceforth, al-Hasan al-Wazzan became known as Leo Africanus. He would live in Rome for the next nine years and serve as an adviser to his Catholic hosts, providing political and military intelligence on the Maghreb.

While all these details about an African man’s encounter with Europe might be fun to reminisce about, what links Africa is a Country’s contributors’ part-time (we all have other jobs) objective—disseminating information, truth-telling, providing a platform for multiplicitous viewpoints of our experience of Africa and its diasporic people, and sometimes calling out those who are in error–is that we modestly attempt to do online at Africa is a Country what Leo Africanus attempted to do in “The Description of Africa,” a book he published while in Italy,

That manuscript was completed in 1526. Its significance lies in the fact that for a long time afterwards, it “shaped European ideas about Africa.” Clifford Geertz, in a review of historian Natalie Zemon Davis’s biography of Africanus, concluded that it was “a remarkable book [that] for centuries [was] a shaping force in the European imagination of Africa.”

What was in it? Africanus’s writing is variously described “a collection of learning, hearsay, and personal anecdote,” and it is often said to reflect the world of someone “straddling two warring cultures.” And invariably, Africanus is similarly described as “a man between two worlds,” and “with a double vision.” For other Western critics, the book was characterized by a “tolerant and non-sectarian tone.” Zemon Davis, the Princeton historian, has written that Africanus offers “the possibility of communication in curiosity in a world divided by violence.” Africanus became, like his book, known for his tolerant views on race, sexuality, Islam (even after he converted) and for getting along with Jewish colleagues.

Why should we refer back to this Early Modern traveler, who, to our modern minds, may come across like a fabricator with too much obsequiousness towards his European masters? Leo Africanus is important for a reason that remains relevant across the centuries: he translated the strange and wonderous things with which he was familiar into knowable language for those who might initially balk at difference.

However, I am not so stupid as to compare myself directly to Leo Africanus. I was born in Cape Town, South Africa, under Apartheid. I went to segregated, working class schools in that city. My parents were domestic workers. I first came to the US in the mid-1990s as a graduate student in Chicago. I returned to South Africa working for a NGO and then lived briefly in London before making Brooklyn my home. I edited some books on postapartheid politics and media culture. But that’s all. Nothing spectacular.

I arrived to live in New York City a few days before 9/11. It was in this post-9/11 climate, when I, and many others like me, were bombarded by negative, a-historical and decontextualized images of Africa. Whether that ahistoricity was connected to the general anti-Muslim atmosphere or not is unclear, but it seemed to be part of a wave of American exceptionalism that threatened to fashion anything un-European into something backward. What were the popular go-to pages about Africa on the blogosphere at the time? They were what can best be described as “development” blogs, concerned with US foreign policy and USAID’s programs and budgets.

Around 2004, I haltingly volunteered to edit an online edition of Chimurenga Magazine, the Cape Town-based literary magazine. However, that effort did not get far and proved frustrating for various reasons, chief among which was my location in New York City. (To their credit, the collective at Chimurenga has since built the magazine’s blog and its online off-shoots, notably Power, Money, Sex, into essential reads.)

Meanwhile in 2005 I started my own blog, choosing Leo Africanus as my avatar, and as the blog’s title. Leo Africanus was hosted on Google Blogger; my posts were infrequent, and I was merely experimenting with the platform. (Sadly, I deleted it. Anyone know how to retrieve the pages?) But already, I had developed a template for it. And it also developed a small, dedicated readership, though I hardly actively promoted the blog. (Among these was someone who used the identity Ibn Battuta; he later turned out to be a successful novelist. But that’s a story for another day.) And I made connections to other early adaptors of blogging—including those on the continent like Jeremy Weate, who ran Naijablog from Abuja, and a few others. The South African blogosphere, to which I paid close attention, was mainly focused on rugby, technology, the country’s version of “the Park Slope mom” blog, and white, rightwing or “liberal” politics.

Also around that time, in the summer of 2007, Tony Karon, who works for Time Magazine and blogged as “The Rootless Cosmopolitan” (his blog title referenced a slur Stalin used for Jews) asked me to write a commentary for his blog on Vanity Fair’s special Africa issue. Reading it now, it sums up a lot of what Africa is a Country’s current postings and preoccupations still are about. Here’s a sample:

Africa, of course, is now everyone’s pet cause. It offers an opportunity to shine for northern political leaders unpopular at home, and for Hollywood actresses and former and current pop stars to be seen doing their bit for humanity by lining up to visit the continent (mainly its children) or pleading its case in Western capitals.

Gradually I started to take blogging more seriously, studied up on developing a style and tone (a mix of snarkiness and irreverence) and purchased a URL, http://theleoafricanus.com, and a month later moved to WordPress. I started blogging more regularly—at least one substantive commentary daily that consisted of 500 words or thereabouts. The commentaries also became more timely, and related to topical events.

In January 2008, I changed the name to Africa is a Country. The name change was deliberate. I had been lampooning journalists, celebrities, public officials and politicians, who had made the elementary mistake of referring to or implying that the continent was one big, monolithic nation (both literally and figuratively). From then on, the blog would combine my commitment to knowledge production, with a nod to the popular, the frivolous, and the crazy. Posts became a mix of links, indented quotes, music, rapid-fire criticism and also some thorough critical investigation.

One year later, the blog ceased being just about my “description of Africa” as I invited others to join me. The first was a former New School student Sonja Uwimana, who had written an MA thesis on celebrity humanitarianism. Possessed of a sharp wit, Sonja proved to be invaluable in that first year of joint blogging, posting as often as people said ridiculous things about Africa and Africans. Later, other graduate students, professors, activists, development workers, journalism students, art critics, novelists, photographers, filmmakers, a DJ, and a curator, among others, came on board. Their names are listed on the sidebar of the landing page. We also have a group of occasional contributors who post when they feel so moved.

That brought its own challenges, but also possibilities. The blog is now more a collective, though it still carries my individual stamp to some degree. Writing posts together online has become standard. We of course give credit to individual writers, but we definitely write some things together. Some have better editing skills (like Neelika Jayawardane, an English professor, and Tom Devriendt, an anthropologist), while others know more about a certain angle connected to the subject of a post or have insight into how the reader will encounter the information—whether we are being snarky for no reason except to show off our wit, or the snark is there for a ‘reason’.

Neelika reminded me recently that her involvement in AIAC removed, for her at least, the isolation of academia, as well as the geographical and intellectual isolation of being a traveler and on-demand educator —formally in the classroom, and informally when someone inevitably spouts some Heart of Darkness nonsense at a gallery opening, a department committee meeting, or at a potluck dinner. Blogging about it the next day—reflecting on the historical weight of ‘Africa’ and the undeniably attractive mythology attached to it, while calling out the idiocy that relies on that mythology as a primary informative source—is infinitely more rewarding than stewing in one’s own juices or venting about it to one friend.

The arrival of Twitter changed the nature of blogging somewhat. Short posts that didn’t require much analysis or reflection would, instead, become tweets; blogging now became mostly for longer, considered pieces. It helped immensely that the blog was no longer a one-person outfit. And along with the changes that we were experiencing at Africa is a Country, blogging as a whole was also changing around this time. We witnessed the emergence of a range of other voices—that of music entrepreneurs, of the African diaspora, of young immigrants engaged in boosterism and identity politics, for example.

Simultaneously, we’ve been wondering what it means to de-center the blog from the US to include not just London and Paris for example, but also African locales; and how to define ourselves as something apart from traditional journalism (some of us have journalism training or have worked as journalists), as well as the slew of new blogs. Finally we’ve arrived at some kind of identity. As Neelika writes on our Facebook page:

The ironic title of the blog, Africa is a Country, acknowledges the re-hashed images of ‘Africa’, undermines those notions, and re-inscribes the image and narrative bank that ‘Africa’ evokes. Beyond the project of ‘re-imaging’ Africa, the blog is a project of re-imagining a nation-ness that exists outside the borders of the classic nation state and continental boundaries. While counter productions like ours are hardly ever ‘networked’ within existing power structures, we use the image field of the blogosphere to construct a new vision of self vis-à-vis networks outside the mainstream. Africa is indeed a ‘country’: the ‘citizens’ of Africa is a Country critique the story and images, contributing to the intellectual dynamics of image consumption and narrative engagement. We aren’t about famine, Bono, or Barack Obama. For that, go to Newsweek.

As with Leo Africanus’s “Description of Africa”—heavy on North Africa and Morocco—there are questions about geographical spread. The blog grew out of my obsessions with reporting and critiquing what passes for analysis about Southern Africa in Anglo-American media in particular. While the blog has adopted a larger continental remit—with the arrival of other contributors enhancing our coverage—it has retained some of its particularly Southern African focus to its detriment, undermining its claims to a greater focus on all corners of Africa and its diaspora. But we’re slowly rectifying this.

Some of us use the blog as a testing ground for ideas we want to publish elsewhere, and at times, we’ve had some success. For example, In May 2008, a post I had written about the deep roots of xenophobia in South Africa—initially published on the Guardian’s Comment is Free site—made it into the newspaper’s print edition. Other pieces that first appeared on Africa is a Country have appeared in Caravan (India), Chimurenga, and Transition Magazine.

We’re also facing new issues—like having to deal with the considerations of a “publication.” Now, we have to think about editorial decisions, an “editorial line,” so as not to contradict previous posts (though we’re very open to that happening) and with vetting contributors.

We continuously find that our words, word for word, have been copied and pasted on other blogs, or turn up in articles of “legitimate” journalists. Because we’re unpaid, attribution and recognition is the only reward. All we ask is a hyperlink, but we don’t always get one.

Topical events also challenge us. #Kony2012, for example, exposed tensions: whether we were letting it define our blog agenda and whether we would be seduced by the attention (one of the posts on #Kony2012 received nearly 30,000 page views on its own in one afternoon). So let me use the madness around #Kony2012 to to reflect on one of the key questions about our blog (something that also dogged Leo Africanus): questions about authenticity and representation.

At some level, we at Africa is a Country were of two minds about getting caught up in the hyped-up “discourse” about #Kony2012 earlier this year. We were, in fact, going to let that circus pass. I had actually blogged last November about the hunt for Joseph Kony; that post included a link to an Iranian (!) TV program where 3 Ugandan experts discussed Barack Obama’s announcement to send advisers to Uganda to deal with Kony’s small, ragtag army. The Ugandans speculated on the reasons for announcement and essentially concluded that Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army had moved on from Uganda and had not been a threat since 2003 and that the real issue for Ugandans was the 26-year reign of Life President Yoweri Museveni.

Of all the posts we did, probably the one representing us the best was one by Elliot Ross, a comparative literature PhD student at Columbia University, that went up three days after the video went online. Offline, in social media and through emails we were contacted by various people and media who were now obsessed with finding out what “African voices” say: meaning, what do ‘authentic’ Africans think about the film—as if the authenticity of the African will make the criticism ‘real’, add ballast to #Kony2012’s fading truthfulness.

Obviously, we agree that the lack of voices of Africans from the regions in which the Lord’s Resistance Army operates (or once operated) is part of the problem in this ‘activist’ film, with its easy ‘to do’ list aimed at the Facebook slacktivist. (After all that’s something that’s part of Africa is a Country’s remit.) But we were not sure how being ‘authentically African’ makes someone a purveyor of opinion on the issue. And we don’t just say that as a blog composed of like-minded people who came together because our politics and our passion for writing intelligently about Africa are aligned in similar ways, rather than because we have our skin colors aligned within the ‘correct’ spectrum, or because we believe our origins give us some sort of authenticity juju.

Africans can also go wrong badly when they draw uninformed (or purely self-interest driven) conclusions about what’s going on in their own backyard. So we were unclear if the ‘authenticity’ of the Africans engaged in (or critiquing) any given ‘African’ situation is the solution per se.

The Western media seemed to be thunderstruck by a sudden “awareness” of critiquing “African voices”: if you report on something happening in Uganda (or name your country) without bothering to talk to any people from said-country (a noble tradition in Western media coverage of the continent since forever), you’re likely to come up with something that looks as utterly crackers as #Kony2012. Since then, they’ve been anxiously casting around for as many Africans as they can find to provide some kind of unchallengeable African Truth. You’re from Sierra Leone? You know something about child soldiers? Oh well, close enough, you’ll do, now tell us what to believe, and please do try to be polite and not say anything horrible about racism, especially if it might be ours.

It was obvious to us that #Kony2012 was/is above all about Americans, not Uganda. It had little to say about Ugandan history or politics and as a media phenomenon, it provided more insight into American mass culture. Elliot’s post analyzed and captured that sentiment. He didn’t have to be “authentic” or have a special pass in order to do better than most of the New York Times staff on Africa’s case.

Sure, Africa is a Country knows how to write snarky responses to all sorts of inane media reports on Africa, but we also recognize that the mentality required for that kind of critique has little to do with Africa or Africans—something I think Leo Africanus knew very well.

August 21, 2012

On Safari

[image error]

If you’re wondering where we are (if you don’t read through to the end of posts) and why the page doesn’t change, we’re on a break this month. However, we’re still tweeting away and updating our Facebook page. We’ll be back on September 1st.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers