Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 528

July 9, 2012

Cabo Verde music: Nha morna, nha Terra

Nho Nani, a bruxo with the fiddle [Photo by Tó Gomes]

I’ve long thought the UN or the OECD ought to measure, as a development indicator, nations’ musical (and cultural) influence per capita. Cape Verde (and Jamaica) would surely top the rankings, while Norway and Germany (Modern Talking, anyone?) would be straggling toward the bottom.While Cesaria Evora is revered in Europe, particularly in France, and by her fellow Mindelenses, she has very many peers, most of whom are less well known abroad: Bana, Ildo Lobo, Norberto Tavares, Os Tubaroes, Luis Morais. Perhaps a rung below these are Maria Alice, Tito Paris, Boy Ge Mendes, and there’s a cadre of relatively young artists — Mayra Andrade, Lura, Tcheka, Sara Tavares — pushing through. But rather than try to write about music I’ve simply posted links to songs that savour of my travels through the islands.

A friend in New York recently wrote me to insist, in response to Sodade, that Tito Paris’s version of the song is the best. You can hear it here. I still prefer Bonga’s sparer interpretation below, in which he can be heard making reference to Sao Nicolau, the home island of its composer Armando Zeferino Soares. Soares was in 2006 recognized at last as the song’s official author after many years of legal dispute.

Morna may be Cape Verde’s best known traditional genre internationally (in part because of Cesaria) but older Cape Verdeans expect, when out for an evening of live music, to also hear livelier funanas, coladeiras, and contratempos.

In Boa Vista I witnessed Nho Nani, a bruxo with the fiddle, segue among multiple genres, mesmerizing the crowd with his bow work. He comes not from Boa Vista but from Fogo, an island in Cape Verde’s southern (“more African”) chain known for wine-making, growing coffee and violin music.

Outside of Sao Vicente, one hears Cabo love and international pop oftener than the more traditional styles. Publicidade for night clubs is usually nothing more than a Suzuki Vitara or Samurai driven at an amble through the main praças of town. Fixed to the roof are enormous speakers blaring looped announcements of upcoming live performances interleaved with snippets from songs currently hotting up the floor. In Sao Nicolau, in Boa Vista, even Mindelo, three songs played over and over: The first two — ‘Moves like Jagger’ by Maroon 5 and P Square’s ‘E no easy’ — are bog-standard autotune global pop.

The third is Cabo love artist Amarildo’s highly infectious Ka bu Tchora (Cabo tears) from the album My Number One. At a Carnaval after party on Sao Nicolau, the large contingent of American peace corps volunteers ground their hips to it as hard as anyone else.

A digression: If you like Cabo love/zouk/kizomba in all its forms and want to trace its evolution and influence, check out Monique Seka’s late 80’s vintage Missounwa and Bisso na Bisso’s remake of Bebe Manga’s ‘Amio’. And if you didn’t think ‘Sinzia’ by Nameless of Kenya was a zouk track, give it another listen.

In Sao Nicolau I received a massive transfusion of digital music, too much to begin sorting through to discover what I liked. And then in Mindelo, I met people that offered recommendations and in this way, discovered Bius and Cordas do Sol, a youngish band out of the island of Santo Antão that successfully melds traditional and contemporary sounds.

In terms of the Morna greats, two names were invariably mentioned: those of Bana and Ildo Lobo. But it was the voice of Jorge Humberto that stirred me. Here are three songs from the album Identidade: Ilha Nha Ceu, Resultod and Novo Olhar.

July 6, 2012

The Photographs of Mary Beth Meehan

In his 2009 anatomy of the financial crisis, First As Tragedy, Then As Farce, Slavoj Žižek noted that ‘it is a sign of the maturity of the US public that there have been no traces of anti-Semitism in their reaction to the financial crisis.’ It remains impossible to generalise about the implications of the crisis for race relations, the positions available in America today – most invisible in the controversies surrounding the murder of Trayvon Martin case or the racist law against immigrants in Arizona – suggest that the application of identity politics to austerity-era politics risk masking the tensions between different economic classes with a false and distracting plurality. And yet the refusal to differentiate between the ’99%’ is surely just as dangerous. Within this contradiction the true nature of race and class relations must lie.

The effects of the economic downturn forced Mary Beth Meehan, a photographer based in New England, to think about race relations. I spoke to Meehan on Skype, from the middle of a rainy London night as daylight flooded into her webcam, and we discussed the problems of representing life in an economic downturn. ‘I started to ask, what happened here? Everyone’s so sad. Everyone’s got someone to blame.’ In an ongoing series – Undocumented – Meehan has been photographing the undocumented residents of several cities. The premise of this project was explicitly political, she tells me, the result of thinking about ‘the way people are dehumanised.’ Frustrated by the limitations conservatives enforced in the representation of those who Arizona State Senator Russell Pearce described as ‘drug smugglers, human smugglers, gang members and child molesters,’ the photographer started to wonder how she could ‘use the medium to contribute something more three-dimensional and humane to this horrible conversation.’

New England, Meehan tells me, has ‘a rich immigrant history,’ which is of course ‘ongoing’. Growing up with Italian and Irish roots in Brockton, Massachusetts, ‘it was a predominantly white and working-class place whose roots are in Western Europe.’ More recently she has watched the racial character of the city change, and seen ‘the old and new clash.’ ‘Witnessing the city decline,’ she adds, ‘the blame [for that] is completely displaced.’

Previous projects have included research into the working-class Italian and Irish communities which populate Brockton, Massachusetts, the city where the photographer was born. The initial subjects of the series were people she met through the bilingual charter school her son attends, and people she knows from previous work in immigrant communities. Many are from Spanish-speaking countries such as Guatemala, Mexico, El Salvador and Columbia, some from Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau. Later she gave speeches in classes for English as a foreign language and encouraged students to contact her.

She circumvented the first problem, of representing her undocumented subjects without exposing them to adverse attention, by photographing the places in which they live. The result of this is a peculiar attention to the dimensions and decoration of rooms and the objects with which they are populated. These things carry an especial significance in the life of those who, she tells me, ‘come for a vacation then never go home.’ There is a visible tension between objects brought from the subject’s country of origin and those accumulated in America. The rooms are often indifferent to their subject, the interiors of temporary residences which lack conscious attention, and here lies what the photographer identifies as ‘an interesting paradox: they are off-camera but their presence is so palpable.’

Meehan conducted interviews with the subjects, and rotating text from these was projected onto the walls of the Rhode Island Community College, when the photographs were exhibited there. ‘You’re hearing this testimony,’ Meehan says, ‘not only the mechanics, how you make do, how you get paid, what street you go to for the permit etcetera.’ The psychological underpinnings of emigration are evidence in the work itself; ‘the interviews happened after the photography. The photography was its own relationships of negotiating.’

‘In some cases I visited classes for English as a foreign language made speeches.’ Meehan encouraged the students to contact her anonymously. ‘So those conversations and those steps, negotiating my entry, framed my experience with the person, and got me in the rooms. Once I was in the rooms my concerns were really aesthetic ones. The pictures which were most successful come together on those levels, come together aesthetically in terms of the emotive quality of a space.’

With her most recent project, Meehan turned her attention back to Brockton. City of Champions – twelve large-scale portraits of residents hung on public buildings in the downtown area – takes its title from the city’s nickname, which refers to the fact that it is the hometown of the boxers Rocky Marciano and Marvin Hagler. The sincere ironies which the name implies are embodied in the image (above), of Turon Andrade, a young boxer of Cape Verdean origin, which has been hung high on a shabby building next to a poster of the two champion fighters which declares ‘Welcome to Brockton’, a juxtaposition which somehow does justice to Meehan’s complex vision of the city.

Most of these images seem to offer their insights – and participate in an overarching argument about present-day and historical Brockton – without any accompanying text. The image below is possibly an exception.

Caption: A nurse shot in her doorway in the middle of the night shows the scars from the bullet and subsequent surgeries. Her attacker had awoken her by pounding on the door, but had mistaken her house for that of the person he was trying to kill.

After this extreme imposition of the arbitrary and motivated violence of city life, the eye is especially sensitive to the way bodies are represented in the rest of the image: smartly-dressed white police officers prepare for the mayor’s inauguration; two women hold each other at the funeral of a 15-year-old boy shot after a row over a video-game; a hooded figure at a downtown homeless camp; the exposed midriff of a woman on Main Street; a woman contorted in prayer against the pew of a Haitian church; cheerleaders of the New England Patriots finger their hair on a windy day; the photograph on the wall of a tailors showing Rocky Marciano punching Jersey Joe Walcott in the face.

In another photograph, former undisputed world middle-weight champion ‘Marvelous’ Marvin Hagler appears, talking to veteran trainer Bill Connolly (right):

Boxing, which has for centuries offered a form of social mobility to members of the dominated classes, is a peculiar example of how the class structure invites individuals to participate in violence to escape the deprivations of city life. The sport, in which members of the working-classes possessing a particular form of bodily mobility – graceful footwork and devastating upper-body strength – sacrifice the right to state protection from attack in exchange for a promised escape from poverty. As a portrait of Brockton, these images present a diverse group of bodies, forced into a variety of different postures by the demands of life and work in the city.

In an interview with the New York Times, Meehan admits that the narrative of the city she heard as a child was “The blacks are ruining my city.” This project presents a narrative vastly more complex, and her website describes the project as one aiming to understand ‘the contradictions [which] embroider life in a once-proud American city some people call “dead.”’ This is also a modest proposal for arts in cities suffering an economic downturn, and Meehan notes that ‘cities who have experienced this decline realise engaging artists is a way of revitalising them.’ She asks about race tensions in London and I mention the riots which happened here last August. ‘There’s nothing that overt,’ she replies, ‘but it does raise the question why isn’t the community more integrated? Why don’t these people run for office?’ This summer she is working with high-school photographers and a historian of modern African history, talking to the students about how they represent an extensions of this history, and the history of New England. Meehan doesn’t know if there are more photographs to be taken (by her) in Brockton, but there are plans for the students’ images to go up around the city, and she hopes that the project will become an annual installation. We certainly hope so: these are photographs of a city worth living in.

Friday Bonus Music Break

Fofo-born Shokanti released a video this week in celebration of Cape Verdean Independence (slipping in those famous words by Amílcar Cabral at the very end). Above. You’ve noticed our blogging went into holiday mode but there’s always time for music. So 9 more below. Brazilian Kamau’s 21/12 finally gets a video; not surprisingly it’s another tribute to skate life:

Warongx (from Khayelitsha) live at Tagoras (Observatory, Cape Town; H/T Sixgun Gospel):

Ghana pop for northern summers. 5Five’s ‘Bossu Kena’:

And some Pan-African pop from Ruff N Smooth:

There seems to exist a standard script for how to record a music video as a diaspora artist on a visit somewhere on the continent (in this case, Abidjan), as Soprano and R.E.D.K. confirm:

Neneh Cherry knows her MF Doom classics (H/T Sarah):

Cameroonian Jovi throws Tabu Ley Rochereau’s ‘Pitié’ in the mix:

True, Youssoupha did that better.

A remix from a different kind: Brussels-based débruit “sampling lost African VHS and reinterpreting discovered African melodies and rhythms.” Seriously though, his music is a lot more exciting than the selling line suggests:

And lastly, via Ricci, “Senegal’s political hip hop for effect”. Red Black:

Africa Express: A Different Breed of Alternative Energy

Guest post by Rosie Spinks

Hear the words ‘alternative energy in Africa’ and you might think of a massive solar plant somewhere in the expanse of the Sahara desert, churning out electricity courtesy of the relentless African sun without a human being in sight.

While that image isn’t entirely inaccurate—construction on the behemoth North African Desertec project began last year in Morocco and is expected to supply 15% of European’s electricity by 2050—it doesn’t involve the group of people that stand to benefit most from alternative energy in Africa: citizens of the continent themselves.

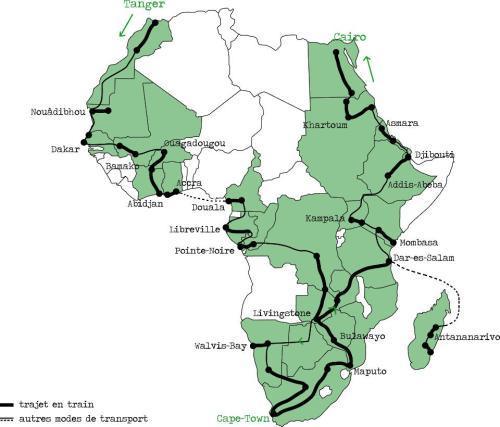

A new project called Africa Express, being carried out by Frenchmen Jeremy Debreu and Claire Guibert with support from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), is bringing attention to a different breed of alternative energy on the continent, one where Africans who lack access to energy are the main beneficiaries.

For a period of ten months, the pair are traveling 20,000 km through 23 countries using trains and buses to survey a range of alternative energy projects. From a community refrigeration project in northern Senegal to a massive hydroelectric dam in Morocco, the size and nature of the projects differ, though they all have one notable in common.

“Africa Express aims to promote energy projects with good practices that are intended to benefit Africans,” Guibert said. “We are not only talking about renewable energy, but with the access to energy to people at the base of the pyramid.”

The United Nations named 2012 as the year of International Sustainability for All, hence the organization’s support of the project, but it’s notable that some of the high profile sponsors of Africa Express are not exactly names you would associate with alternative energy. In addition to the non-industry sponsors of the UNEP and the African Development Bank, energy industry giants EDF energy and Schneider Electric are listed as main backers. Asked how he would respond to criticism from environmentalists on this point, Debreu explained the logic behind the involvement of such large energy corporations.

“It is true that part of the business model of Schneider Electric or EDF is based on fossil fuels and [conventional energy sources],” Debreu said. “But for them, access to energy is more and more linked to the development of sustainable energy and new development models. This is a strategic answer for them for different reasons.”

Guibert also added that the 18 projects they are visiting were chosen independently and without input from their sponsors. After mapping the train routes and existing transport networks they would use to get around the continent, the pair consulted a panel of experts to select roughly 20 projects from 100 potential options. The selection criteria was based on economic, social and environmental benefits, impact on biodiversity, and replicability.

Guibert and Debreu are planning to produce a documentary and a white paper outlining the findings of their trip, which they hope will show what kinds of projects are successful and fill a notable void of research about alternative energy on the continent. They also maintain that central to the ethos of their project is the idea that the model of NGOs and foreign aid fixing Africa’s problems is not effective.

The most successful projects so far, they say, are those that train the local population to become contributors to the project and not just beneficiaries, that have support of local authorities, and have a self-sustaining business plan rather than an expectation of long-term aid.

“The biggest challenge is actually to understand that a centralized electricity network over [a whole] country is not the solution everywhere, especially in countries where there are a lot of little rural villages,” Debreu said. “That is why we think that generally, projects developed by NGOs without any local implementation are going to fail.”

A highlight of the trip so far has been the “ecovillages program” initiated by the Senegalese government. Far from the tourist resort that the name suggests, the 21 villages already initiated in the scheme form de-centralized electricity networks, which are using small-scale solar charging stations and bio-digestors in rural areas which the national energy company can’t yet afford to electrify.

Debreu and Guibert are also excited about the level of social entrepreneurship they have seen, such as individuals engineering improved cookstoves and briquettes as an alternative to wood for fuel.

A rural cooperative they visited in Burkina Faso was able to meet local demand for energy just one year after opening by offering training to local technicians, which meant problems could be solved easily when they arose.

“It’s very important not only to consider that alternative energy is benefiting lives, but also to take into account individual and ongoing training before and after the installation.”

You can follow the progress of Africa Express on Facebook and Twitter.

* Rosie Spinks is a London-based freelance journalist. Her work has been featured in publications including Sierra magazine, GOOD magazine, The Ecologist, Urban Times, EcoSalon, Matador Network, and the Guardian Environment Network. You can follow her on Twitter and Tumblr.

July 4, 2012

Independence Day Edition: What’s more ‘American’ than Chevron Corporation?

July 4. U.S. Day of Independence. What’s more ‘American’ than … Chevron Corporation? It’s pretty much always in the top 5 of U.S. based corporations. It’s deeply involved with everything having anything to do with energy or power. Oil, gas, geothermal. You name it, Chevron’s there, but not like a good neighbor. It’s got history, well over a century of environmental ‘intrusions’. And its corporate logo is red, white and blue. If Africa’s a country, the USA is a red white and blue multinational corporation. So, let’s celebrate Chevron.

Or better, let’s celebrate the Nigerian women who shut it down for a couple weeks, ten years ago, July 2002. At that time, a few hundred unarmed Itsekiri women, mostly mothers and grandmothers, occupied the Chevron Oil Tank Farm in Escravos. Their weapon? Their threat? Nudity. That threat of stripping themselves naked shut down the multi-billion dollar plant for eleven days. As Sokari Ekine explained, “The mere threat of it would send people running. These are mature women and for mothers and grandmothers to threaten to strip is the most powerful thing they can do. It’s a very, very strong weapon. Chevron is American, but they have Nigerian men working for them, and women are held in particular esteem in Nigeria – and if a woman of 40 or 70 takes her clothes off a man is just going to freeze.”

The men froze. And so did the oil for a while.

And then there were ‘negotiations’. Emem Okon is a feminist activist organizer in the Niger Delta, who has consistently pushed and prodded Chevron. She founded the Kebetkache Women & Development Centre, in Nigeria, and is a key member in the global True Cost of Chevron network. She is more than a thorn in the side of Chevron. She’s a bomb in the lap and a stake through the heart. Emem Okon is the feminist face of petro-sexual emancipatory politics.

Here’s how Emem Okon sees the ‘negotiations’ that followed:

There were negotiations. But the reason the women took over the oil tank farm was that Chevron and other oil companies is fond of negotiating with only the men, because the community leadership comprises of only the men and the male youths. So because Chevron was not listening to the women and not paying attention to the concerns and interests of the women, the women decided to mobilize and organize, and took over the oil tank farm, because they wanted to get the attention of Chevron. They stopped production on the oil tank farm for 11 days, and they insisted that Chevron management staff should come down to Burutu community to discuss with them. But by the time Chevron decided to come and discuss and negotiate with the women, the process was taken over by the men. The state government sent representatives, the traditional rulers sent representatives, and it was only two women that was part of the negotiation.

Chevron makes it a policy of not listening to the women, and in particular not listening to strong activist women, like Emem Okon. In May 2010, Okon, as a legal proxy holder, tried to attend the Chevron’s shareholders meeting in Houston. She wanted to speak to the shareholders Chevron’s devastating environmental impact in the Delta. She was barred. So were sixteen other community representatives from around the world. Five members of the True Cost of Chevron coalition were arrested.

This year, Chevron let Emem Okon speak – for a whole two minutes. In two minutes, Emem Okon had enough time to state the obvious. Chevron lies in its reports from the Niger Delta. Chevron’s activities in the Niger Delta – poisoning the water, ruining the land, devastating the local economies – directly attack women: women as fisher-folk and as farmers, women as mothers, women as community members, women as women: “The women of the Niger Delta call on Chevron and every other oil company to leave the Niger Delta oil under the ground. Stop destroying our environment. Let our oil be.”

The women of the Niger Delta are calling. They have had enough of Chevron’s charity, violence, exploitation and duplicity. Want to celebrate independence this year? Support Emem Okon and the women of the Niger Delta.

* Photo Credit: Jonathan McIntosh

July 3, 2012

In North Kivu, R&B is pure art

The text that comes with Agata Pietron’s photographs of youth in Kiwanja and Rutshuru (North Kivu, Congo) flirts with the clichés (the Conrad reference; the brave missionaries; the photographer is a “muzungu” who “discovers” youth who are into R&B and rap, wearing “Chinese made sportswear knockoffs”; and despite the “absurd” circumstances people have “strong spirits”), but her portraits are striking, and introduce us to a music scene we won’t find on Youtube. More below:

And the full series on Pietron’s website.

July 2, 2012

My delicious ‘Afrigasm’

We’re always ready to travel far to get satisfaction. God knows we’re prepared to get hot and sweaty. So when, after months of romanticizing and exoticizing, our dreams finally take off, there is only one thought on our mind: Oh Africa, I’m coming! The experience of the Afrigasm is limited to a particular group. We tend to be white Euro-Americans and are drawn to Sub Saharan Africa by an urge to explore and to do good, or by a more existential desire for an encounter with radical difference. We come as tourists, interns, entrepreneurs, volunteers and exchange students. Quite a few of us engage in sustainable development projects, while others’ efforts are more short-term in nature or draw some criticism here and there (think Invisible Children). What we all share, however (and this is crucial to get an Afrigasm), is an “Africa Sweet Spot,” which we express in This is Africa-themed stories that keep the home-front updated about our African adventures. We used to write endless emails about these experiences, but now we post them on our blogs and successive FB posts. ‘This is Africa’ or TIA, connotes the exotic and romantic randomness that we Western visitors attach to Africa. TIA sentiments are the foreplay of our Afrigasms, and they overwhelm us every time we witness ‘the hopeless continent’ in action.

The experience of the Afrigasm is limited to a particular group. We tend to be white Euro-Americans and are drawn to Sub Saharan Africa by an urge to explore and to do good, or by a more existential desire for an encounter with radical difference. We come as tourists, interns, entrepreneurs, volunteers and exchange students. Quite a few of us engage in sustainable development projects, while others’ efforts are more short-term in nature or draw some criticism here and there (think Invisible Children). What we all share, however (and this is crucial to get an Afrigasm), is an “Africa Sweet Spot,” which we express in This is Africa-themed stories that keep the home-front updated about our African adventures. We used to write endless emails about these experiences, but now we post them on our blogs and successive FB posts. ‘This is Africa’ or TIA, connotes the exotic and romantic randomness that we Western visitors attach to Africa. TIA sentiments are the foreplay of our Afrigasms, and they overwhelm us every time we witness ‘the hopeless continent’ in action.

Afrigasms feel as good as they do because they confirm the way media (and our own local mythologies, passed around by and down from friends and family) taught us to view the continent: Mostly a place of hunger, disease, helplessness and struggle. They consolidate the position of the African other. This African other is slow, late, poor, powerless, dresses funny, drips exotic, and speaks with the television African accent. He or she always has time to chat. No rush. We admire his courage to live by the day, we adore her children and can’t get enough of the amazing stories he has to tell: everything from tragic sob-stories to courageous struggle narratives. We respond open-mouthed with “Oh my God, so you were beaten up by the apartheid police”? Afrigasm! Even when we’re hungrily waiting for our (super cheap!) sushi and cocktail plate (should we add ‘in Cape Town’ here?), only to find out the waiter mixed up the Mohito with a ToffeeBerry Martini, we shake our heads, smile, think TIA and whoop! … Exactly.

Don’t be mistaken, we are aware of our stately mix of white guilt and our distaste for our colonial capitalist ancestors; Eish, they were arrogant! But today, we have the chance to make up for it. Or at least a little bit. Driven by a remix of the White Man’s Burden, thousands of us are currently pursuing Afrigasms. Africa’s landscape, chaos, slowness, ever-so-friendly but powerless people, and last but not least, Africa’s endearing children offer us an emotionally fulfilling experience which is unique in its gratifying potential. That’s how these same children – with or without consent – often end up in picture frames in Eindhoven, Hannover or Tennessee.

Though many consider Cape Town too developed to be a part of Africa and prefer to detach it from the rest of the homogenously-postulated continent, it still manages to deliver Afrigasms wholesale. “I just feel happier here, I love this city!” Of course we do. Even with a study loan or a – by Western standards – modest income, Cape Town offers us the opportunity to move up a social class and enjoy a standard of living many of us could never afford back home. Try having your sushi and cocktails in Stuttgart or Den Haag thrice a week with a study loan. (Didn’t think so. But can you blame us?)

Though many consider Cape Town too developed to be a part of Africa and prefer to detach it from the rest of the homogenously-postulated continent, it still manages to deliver Afrigasms wholesale. “I just feel happier here, I love this city!” Of course we do. Even with a study loan or a – by Western standards – modest income, Cape Town offers us the opportunity to move up a social class and enjoy a standard of living many of us could never afford back home. Try having your sushi and cocktails in Stuttgart or Den Haag thrice a week with a study loan. (Didn’t think so. But can you blame us?)

Yet it’s not so much the high life in itself that turns our Africa Sweet Spot on. Rather, it’s the combination of many things; yes, the joyful upper class experience in places like the Radisson, Sheraton or Cape Town’s Camps Bay, and the chance to stroll the streets in bohemian Observatory in bare feet without worrying about tetanus turn us on; but so do the ‘do-good’ opportunities on every street corner and the chance to generously reward our cleaning lady with a bag of left-overs, whilst paying her the equivalent of a couple of Stockholmian espressos for a day of labor.

So every time we see a broken-down car being pushed down the street or when we find ourselves waiting for a late taxi and catch a ‘umlungu’ or ‘Hey Lady!’ from a bypassing overcrowded bus, we sigh, we smile, we think TIA and whoop!

It is these kinds of TIA experiences that are often written home about. Whilst seemingly innocent and often written with affection, it is these nonstories and their reproducing position within the dominant western discourse on Africa that keep our distorted perceptions and disturbing stereotypes alive. They subtly legitimize the occasional KFC and Big Black Mambo joke, when (guess what!) they’re racist! It’s this same legitimizing power that made the editor of the Dutch magazine Jackie wonder why people were overreacting to her magazine’s lively explanation on how to dress like a N* bitch, late last year. The Western discourse on Africa, grounded in centuries-old traditions of rigid stereotyping, continues to define the African ‘other’ who is most often portrayed as a powerless victim or random struggler.

Successful and actualized Africans hardly ever get a place in this discourse. Nor does functional Africa. Because they don’t appeal to our more ‘real’ African experiences (which are, needless to say, different in various cities, locales, and regions, and dependent on the day, weather, our mood/mood of the persons we encounter, and maybe also the way the wind blew) and don’t correspond with what media has told us ‘Africa’ is. The problem is that by disseminating and singling out the TIA non-stories, we ourselves actively perpetuate the same colonial discourse that has dominated Western media and legitimized white domination for centuries. We choose not to see our own experiences as random, individualized, and varied. The assertive, self-reliant, successful, confident, functional and orderly version of the many ‘Africas’ out there won’t help string our special experience to those millions of TIAs that came before it.

My Dutch driver’s license is about to expire, so I applied for a South African driver’s test today. Around 2pm I entered my local traffic department office, where a lady approached me and asked me how she could assist me. Professionally. She directed me to the appropriate queue to get my application form stamped. Slickly. The queue moved quickly and I got my stamp within three minutes. Efficiently. The lady behind the counter referred me to office 14 where I would undergo an eye test. Logically. Less than 10 minutes later I found myself staring through a modern machine, following instructions to count differently-sized squares. Finally, I paid my 69 Rand application fee and walked out with a printout listing the date for my exam. It stressed I had to be on time.

A nonstory indeed. Hardly an experience, really. But it’s a manifestation of something that shouldn’t be ignored and is worth writing home about: It’s Functional Africa. Quite the turn-on, isn’t it?

* Maria Hengeveld studies Sociology and Gender at the University of Cape Town. She currently works for the Children’s Radio Foundation. Previously, she blogged here (with TJ Tallie) about pinkwashing South Africa. The images are by Mimi Cherono Ng’ok, a Kenyan photographer working in Nairobi.

The failed index from hell*

We at Africa is a Country think Foreign Policy and the Fund for Peace should either radically rethink the Failed States Index, which they publish in collaboration each year, or abandon it altogether. We just can’t take it seriously: It’s a failed index.

This year, pro forma, almost the entire African continent shows up on the Failed States map in the guiltiest shade of red. The accusation is that with a handful of exceptions, African states are failing in 2012. But what does this tell us? What does it actually mean? Frankly, we have no idea. The index is so flawed in its conception, so incoherent in its structuring criteria, and so misleading in its presentation that from the perspective of those who live or work in those places condemned as failures, it’s difficult to receive the ranking as anything more than a predictable annual canard issued from Washington, D.C. against non-Western — and particularly African — nations.

The problem is that there are any number of reasons why the Fund for Peace might decide that a state is failing. The Washington-based think tank has a methodology of sorts, but Foreign Policy insists on making the list accessible primarily through a series of “Postcards from Hell.” Flipping through the slide show, it’s impossible to shrug off the suspicion that the whole affair is a sloppy cocktail of cultural bigotries and liberal-democratic commonplaces — a faux-empirical sham that packs quite a nasty racialized aftertaste. How do we know if a state is failing or not? Old chestnuts like the rule of law are certainly considered, but also in play are things like economic growth, economic “success,” poverty, inequality, corruption, nonstate violence, state violence, human rights abuses, body counts, terrorism, health care, “fragility,” political dissent, social divisions, and levels of authoritarianism. And yes, we’ll be indexing all of those at once, and more.

The golden principle by which this muddle is to be marshaled oh-so-objectively into a grand spectrum of state failure coefficients is apparently the idea of “stability.” But is it really? Well, if you’re an Arab Spring country, then yes, it’s the “instability” of revolution or popular revolt that has put you in the red this year. Sorry about that. But if you’re North Korea (the paradigmatic failed state in the U.S. imagination — hence why Zimbabwe is often branded “Africa’s North Korea”), it’s because you’re far too stable. If stability is the key to all this, and yet there’s an imperative for places like North Korea still to be ranked as failures, then we’re in trouble. The cart has long ago overtaken the horse. It would be very difficult indeed to conceive of a more stable form of rule than having power descend smoothly down three generations of the same family over six decades and more (perhaps the Bushes will pull off something like this one day). And, of course, it helps if the names of overweening rulers are spelled correctly: Cameroonian readers of the slide show were startled to discover that they had been led for many years by someone by the name of “Paul Abiye,” of whom they had never heard (the spelling has since been corrected).

Clearly, the value of stability to any society is uncertain and subjective. Foreign Policy explains to its readers that Malawi (No. 36 on this year’s index) is to be considered a failed state on account of the 19 people killed by police during popular protests against Bingu wa Mutharika’s government a year ago. Yet such dissent is evidence of the strength of Malawian civil society and the determination of ordinary Malawians not to get screwed by their government. Malawi is undoubtedly better off for these protests, not worse. What makes the country’s listing as a failed state look even sillier is that Malawi recently endured a blissfully peaceful transition of power following Mutharika’s sudden death, with constitutional guidelines scrupulously adhered to despite the vested interests of many of the country’s ruling class.

One of our readers, the cartographer Jacques Enaudeau, called the index “a developmentalist ode to no-matter-what political stability and linear history.” He’s right, but as we’ve seen this stability fetish only applies to those states perceived as non-totalitarian. So how exactly can a democratic country like, say, Nigeria ever hope to satisfy the whimsical judgment of Foreign Policy magazine? The Occupy Nigeria movement that demonstrated against corruption and the removal of the country’s fuel subsidy in January was a peaceful mass movement that achieved major gains for working people. It was a thoroughly global protest, with Nigerians in the diaspora taking to the streets of Brussels, London, New York, and Washington, D.C., to demand better governance in Nigeria. Yet these protests are listed on the country’s “postcard” alongside terrorist attacks by Boko Haram as equal evidence of Nigeria’s “hellishness.” For some reason, the postcard neglects to mention the extraordinary spectacle of protesters in Nigerian cities standing guard outside each other’s places of worship — Muslims outside churches, Christians at the doors of mosques — so that each group could pray without fear of further bombings.

Many of the Postcards from Hell, in fact, simply show popular protests taking place, as though dissent and social demonstrations are themselves signs of state failure. What kind of half-baked political theory is this? Maybe protests are bad for business and troublesome, but for whom exactly? And are we ranking the state or the society? Or both at once?

It baffles us that a U.S. magazine that prides itself on attempting to offer smart, detailed, historically rich analysis of other countries should so rejoice in deliberately rejecting nuance and complexity, offering a single emotive image as the representation of “what living in a failed state looks like.” The decision to recycle old photographs (a quick glance indicates that Mozambique’s, for example, is from 2010, while Madagascar’s is from 2009) suggests that some of these states have stubbornly refused to look sufficiently like failed ones for quite a while. So who loses out when Foreign Policy does something like this? We don’t think the answer is as obvious as it might first appear. Another of our readers, Sara Valek, writes, “There is so much more to a country than one photograph. I feel sorry for the people viewing this article who now only have this image in their brains about Mozambique, as opposed to the beauty that I know and love.”

The Postcards from Hell also insist that there are no white people in this year’s story of state failure — not even the people of Greece, who are informed — surely to their incredulity — that they are living in one of the 40 most stable nations in the world. Egypt is ranked 31st, but nowhere in the account of “just how it came to be that way” is there a mention of the annual $1.3 billion of U.S. military aid (recently reinstated) that continues to complicate attempts to establish parliamentary democracy in the country. European colonialism and the Cold War are scarcely mentioned, yet the reader is somehow expected to form an adequate understanding of the problems faced today by a country like Angola. Is late 20th-century history too far back in the past for Foreign Policy to bother itself with?

Flicking through the Postcards, we can’t help wondering what can possibly be gained through this bombastic annual display of geopolitical smugness. Why not choose to be self-critical instead of blithely rubbishing faraway countries every summer?

There will never be a Postcard from Hell that bears a picture of an American street. But what if there were? What would go on there? Might it not apply the very same criteria that condemns much of Africa and lament the deeply corrupt political system that makes legislative progress virtually impossible, inhibits the establishment of truly pluralistic multiparty politics, places the bulk of power in the hands of unaccountable corporations, and offers only the very rich the chance to pursue successful political careers? It might make mention, too, of the baffling lack of affordable public health care, the rapidly growing inequality that can only foment social unrest, or the way in which young men of color continue to be harassed by state police. Maybe we could refer to these police officers as “security forces loyal to the current regime.”

Nor must we forget the enduring popularity of capital punishment, the country’s ongoing program of extrajudicial detention and killing that proceeds without any substantial accountability, and the nation’s vast stockpile of nuclear weapons, which proliferates in shameless contravention of the international commitments made by the United States. America’s Postcard might add that, in recent years, its soldiers, humanitarians all, have become notorious around the world for choosing to record footage of the atrocities they commit on mobile devices, in order to share these images with friends and colleagues. It would certainly bemoan the beatings and intimidation meted out to the many Occupy protestors who demonstrated peacefully in American cities last fall. Perhaps the picture could be of the moment last year when a police officer seized a U.C.-Berkeley college professor by the hair and flung her to the ground.

* This post first appeared on ForeignPolicy.com.

June 27, 2012

Euro 2012 Semi-Final Preview: Mozambique vs Spain

Here in Maputo there’s only one thing on tonight: Portugal’s clash with Spain in the semi-finals of Euro 2012. Fancy bars are pushing up their cover prices and there are images of Cristiano Ronaldo all over the city centre. All the matches in the tournament have been watched with interest here, but when Cristiano Ronaldo stooped to head Portugal to victory against the Czech Republic last week, most Mozambican football fans were on their feet, whooping and high-fiving one another as though it were the Mambas, their own selecção, that had triumphed.

After that game, I suggested — much too loudly — that Ronaldo is still some way off the level of play sustained by his nemesis, Lionel Messi. This heresy draws scowls from all corners of the pub and I am soon put to rights as to Ronaldo’s undeniable superiority. I admit that I am surprised to find such fervour attached to the football team of Mozambique’s former coloniser. We Scots tend to root for a shape-shifting nation by the name of “ABE” (Anyone But England) in such competitions, with our own side still languishing in the doldrums. “The Portuguese are our brothers,” my friend explains. “And of course, there was Eusébio.”

In a typically illuminating piece, Laurent Dubois yesterday looked at how the ongoing Euro championship offers a window into ”how histories of immigration have reshaped the world of European football”. Dubois is acutely sensitive to how international football provides a stage for the creation of national symbols and myths. He writes:

During international football competitions like the European Cup, eleven players briefly become their country, for a time, on the pitch. A nation is a difficult thing to grasp: unpalpable, mythic, flighty. Historians might labor away to define the precise contours of a country’s culture and institutions, and even sometimes attempt to delineate it’s soul, while political leaders try mightily (and persistently fail) to stand as representatives of it’s ideals. But in a way there is nothing quite so tactile, so real, as the way a team represents a nation: during their time on the pitch, they have in their hands a small sliver of the country’s destiny. And in those miraculous and memorable moments when individual trajectories intersect with a national sporting victory, sometimes biographies and histories seem briefly to meld. At such moments, the players who inhabit the crossroads of sporting and national history –Maradona in 1986, Zidane in 1998 — become icons, even saints.

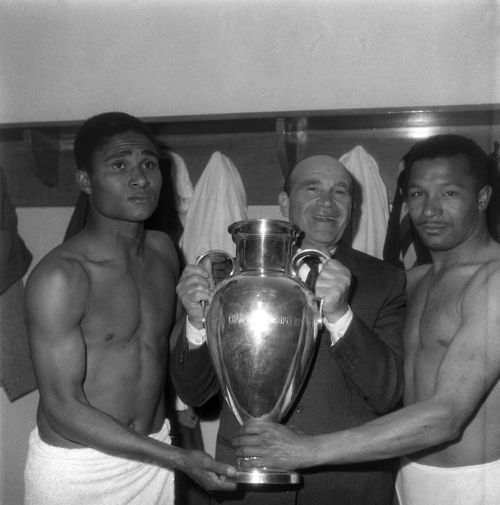

In Maputo, soccer’s communion of saints is presided over by Eusébio, the local boy. With Eusébio as the totem for the great Portuguese side of the 1960s, Mozambicans developed the enduring attachment to the Portuguese national team that will see them cheering on Paulo Bento’s players later today. Nicknamed “Os Magriços”, Eusébio’s side enjoyed an enthralling run to third-place at the 1966 World Cup, and around that period many other Mozambicans joined him in the red and green: players such as Mário Coluna (pictured above with Eusébio and the European Cup, Coluna captained the team at the 1966 World Cup, played in five European finals with Benfica, and later became president of the Mozambican Football Association and Minister for Sport), the extraordinary forward Matateu (who scored 218 goals in 289 Primeira Liga games for FC Beleneses), and Matateu’s brother Vicente Lucas (whom Pelé called the greatest defender he had ever faced) Hilário da Conceição, and Alberto da Costa Pereira. Together they could have made Mozambique a fearsome force in world football, but at the time there was no independent Mozambican nation, and no Mozambican national side to play for. Yet if there was something coercive about Mozambique’s golden generation representing the country that had colonised them, Mozambicans still felt a great thrill at seeing their countrymen becoming world-beaters. The bond with the vehicle for that pride — the Portuguese national team — still holds.

Not all former colonies can look back to such a moment, and yet for the most part it seems that African fans retain a surprising affection for old colonisers when it comes to international tournaments. Apparently in South Africa pretty well everyone was, as usual, behind Hodgson’s team. This is probably as much to do with SuperSport’s ongoing conquest of the South African weekend by means of the English league (and players who have excelled in it during its rise such as Steven Gerrard and Wayne Rooney) as it is with old colonial ties. It will be interesting to see, as immigration continues to shape the European game, whether these loyalties begin to fracture. Ghanaian affection for England may have taken on more of an edge in this tournament with Danny Wellbeck starring for them, but in their quarter final Italy fielded an even better Ghanaian striker in Mario Balotelli.

Top tweeter @Kweligee said he reckoned he was one out of a total of possibly just two Kenyans, worldwide, who reveled in Scottish-style schadenfreude as England were beaten by Italy at the weekend. He suggested that our glee was the cheapest possible expression of our postcolonial condition. Yet isn’t there something enjoyable about choosing to flout the Anglophone broadcasting edict according to which one must cheer for England as a matter of public decency, and stubbornly backing “Johnny Foreigner” instead?

Tunisian Art Riots and the Play of the Serious

The long running art show, Printemps des Arts, held in La Marsa, a wealthier suburb of Tunisia, was the site of riots and attacks against art that incited the religious rancor among Salafi fundamentalists. On June 10, the last day of the exhibition, fundamentalists were incited to wreak havoc on the art when a government official (referred to as a bailiff) visited the exhibition, took photos and brought them back to show to a mosque populated by Salafist zealots. Calls for attacks against artists, and photos of the offending images on exhibition were circulated through the use of social media. In this case Facebook was the launch pad for a compilation video of images and text, as well as for a recorded statement from Cheikh Houcine Laabidi, an imam at the Zitouna mosque, denouncing the artists involved. Groups of agitators went back later that night, and the next, throwing bombs, burning and slashing artworks, and contending with police. The government subsequently shut down the exhibition.

In the wake of the ensuing riots and threats, and in a bid for defense, the Tunisian Union of Artists (SMAP) held a press conference on June 15 to address these attacks. In particular the speakers addressed the comments of the Culture Minster, Mehdi Mabrouk, who stated, “Art’s role is to provoke. Sometimes art provokes which is its role. But there is a huge difference between provocation and attacks on religious symbols.” What began as a positive statement upholding artistic license ends up doubling back on itself and calling into question government assurance of artists’ freedom of speech. In response to this statement, Amor Ghedamsi, head of SMAP, has said: “Even though [Mabrouk] has not yet censored artwork, he presented an ideology that paves the way for censorship. This is a conspiracy to brainwash public opinion against artists.” As the Tunisian artists see it, they are facing increased alienation from their government and from Salafist agitators who, by condemning the artists as infidels, are trying to stir up and use religious sentiment as a means of co-opting a nationalist agenda.

So, how does one fight back?

We believe that it is mere idiocy and folly to reduce modern art, as some desire, to a fanaticism for any particular religion, race or nation.

Along these lines we see only the imprisonment of thought, whereas art is known to be an exchange of thought and emotions shared by all humanity, one that knows not these artificial boundaries.

O men of art, men of letters! Let us take up the challenge together! We stand absolutely as one with this degenerate art. In it resides all the hopes of the future.

Even though the lines above were taken from Egyptian artist Georges Henein’s manifesto “Long Live Degenerate Art”, signed in 1938 by artists and writers living in Cairo, perhaps we can draw a lite parallel between then and now.

Working within an environment of political transition, volatile social conditions, and general unrest contemporary Tunisian artists are facing similar conditions to Egyptian artists of the 1930s and 40s. Though Egyptian artists in the Surrealist movement were reacting against different factors, namely academic painting, the Nazi banning of modernist art in Europe, and nationalist sentiment, their focus on social ills, inequalities, and popular culture as a means of advocating for reform and increased social dialogue, parallels current Tunisian artistic aims and discourse.

But perhaps there is an added element within Tunisian contemporary art that can be found in many of the contested works on display at Printemps, namely the tension that exists between the playful and the serious, especially in the works of a religious nature. Johan Goud argues (in At The Crossroads of Art and Religion. Imagination, Commitment, Transcendence) that “seriousness needs the perspective that play provides to be able to remain itself.” Thus, the unease we may feel in the gap between play (or humor) and seriousness in religious art, permits the needed distance to accrue between the aesthetic contemplation of the work and the subject of the work, which then, in Goud’s opinion, allows for new facets of interpretation that otherwise may be stymied in normal contexts. Take for example the canvas by artist Ismat Ben Moussa portraying a cartoon version of an angry Salafist, replete with smoke fuming from the ears, zombie eyes, and a fang toothed mouth. Normally, religious men are treated and depicted with respect, but here the artist’s mockery of the angry religious zealot pokes fun at the serious political struggles, and religious undercurrents, roughing up Tunisian society.

A second example is the work which depicts a trail of ants coming out of a schoolbag forming the words “Glory to God”. Though considered blasphemous by the rioters, the canvas did not attempt to depict Allah in a figural manner, which is prescribed against in Islamic doctrine. Its message is also in keeping with a section of the Qur’an, the Surat An-Naml (27:16-19). Its playful use of the insect as an artistic medium, calls upon the viewer to re-examine the verse, and the place of the very small, and potential overlooked (who do indeed have a voice, even a female voice!), in society.

In a more democratic not-quite-a-manifesto spirit, The Tunisian collective for Art, Culture and Freedom has created an online petition as their own modern day call to action. The petition lists some of the artworks called into question, addresses the resulting negative attacks against the artists, and appeals for solidarity among fellow artists and the wider media, in an attempt to foster support for freedom of artistic license for all Tunisian artists.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers