Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 531

June 8, 2012

Flame-Grilled Chicken Politics

I am writing this from Cape Town, where it took me a while to load the 53 seconds video of the latest Nando’s ad (above) on Youtube, so I am not sure how “it is going viral” here. (Though viral here also means 300,000 people viewed it on online.) For those who don’t know, Nando’s is the South African fast food chicken chain taking on a “global” footprint–well as far as I know in the UK, US (in Washington D.C)., Australia, Dubai and a few African countries. As for the ad, Nando’s claims it is a comment on xenophobia. For those who have or can’t watch it online, it opens with scenes of black undocumented migrants crossing the country’s border while a voice over says, “You know what’s wrong with South Africa? It’s all you foreigners.” It then cuts in quick succession to a series of stereotypes and references to Chinese (yes, offloading good), Indians (Oriental Plaza, I think), Kenyans (in running gear), Afrikaners (yes, farmer with dog in front seat and black workers in the back), Zulus, Tswanas, and Sothos, among others, all disappearing in puffs of smoke. The only person who survives the puff of smoke effect is “a traditional Khoisan man” who, using expletives, says he’s not going anywhere because “you found us here.”

The public broadcaster, SABC, then announced it wouldn’t show the ad on its channels, and now satellite operator DStv as well as terrestrial channel ETV have done the same thing. This played well into Nando’s marketing strategy. Its ads thrives on political controversy. The result would be people talking about them and more sales of peri peri chicken. This is chicken nationalism. It does not help that South Africans–remember the country where the media acts like they’re writing/reporting from Somalia and North Korea as political researcher Steven Friedman puts it so well–are now obsessed with saying everything is being banned. So of course when the SABC–synonymous with the ANC “dictatorship” in the media and the suburbs, clumsily announced its decision (its spokesman said the SABC was concerned “that the public might interpret [the ad] differently”), the papers insinuated that it was a “political” decision and that the ad was “banned.” Nando’s CEO went on about “freedom of expression” and “censorship.” (He wasn’t saying anything about how happy he was about the whole thing blowing up.) Of course you can still watch it online. But what about the ad itself? The reporting here on the content of the ad has been very poor–to put it mildly.

I actually find the ad unfunny and problematic. It basically endorses, on the one hand, the white right-wing parliamentarian Pieter Mulder’s willful denial of South Africa’s violent history especially on land dispossession (and with aspects of the sunny politics of the Democratic Alliance) and on the other hand it bolsters the similarly ahistorical and ethnocentric claims of coloured nationalists who are all “Khoisan” now (that category in itself is a 20th century construction since the two–Khoi and San–that make up “Khoisan” are separate, distinct peoples). In the end this is about Nando’s wanting attention and it got it. Nando’s wants to sell chicken and it pretends that it has good “politics,” though we know that politics goes only so far.

I then ask around the AIAC “office” for comments. Here’s an edited version of the conversation.

Melissa Levin: I totally agree with you. That’s how I read it too. That we are all ‘colonizers’ and the fight was one between groups of land invaders. In addition, it persists in buoying the nonsense about cultural identity, diversity, multiple groups making up the South African fabric–no majorities and minorities, blacks and whites, but Xhosas, Afrikaners, etcetera. “We are all minorities now.” The contest over the meaning and content of public life is quite brutal it seems.

Daniel Magaziner: Unfunny and problematic is putting it kindly. The ad traffics in the long disproved ‘empty-land’ thesis on the early 20th century, which held that South Africa’s current residents–whether white or black–were conquerors, who had displaced the subcontinent’s legitimate inhabitants. If both whites and blacks were conquerors, than what right could Africans possibly have to cry foul at land dispossession and segregation? Bantu-speakers (the ad’s fast disappearing array of Zulus, Tswanas, Sothos, etcetera) had simply lost the great game of imperial conquest to the whites. Boo hoo. Let’s not even dwell on how the ad’s comparison between Kenya and Lesotho, Cameroon and ‘Zululand’ traffics in apartheid era claims that Bantu-speakers’ legitimate homes were in the Bantustans (including those supposedly pure ethnic enclaves beyond South Africa’s ‘white’ borders), just as whites were legitimate in their white republic. And the stereotypes, oh, the stereotypes. Although I enjoyed the running Kenyans, I found the the Boer in the bakkie with the dog in front and the workers in the back a little too real. Nando’s chicken is delicious; its historiography and social criticism less so.

Basia Lewondowska Cummings (@mishearance): It’s strange that they portray the ‘Khoisan’ guy at the end in some with a kind of hip hop style aggressive cool. Why make him swear? I suppose the only interesting thing the advert throws up, other than a brilliant array of stereotypes, some dubious looking chicken and a poke at xenophobia, is: whose place is it now to question social realities like xenophobia?

It’s interesting why Nando’s feel they can/should comment on it, and think that it’s a lucrative means of advertising their product. And if advertising will increasingly become a place to address these concerns, can we predict that it will continue to fall into such crude, stereotypical, de-contextualised ‘advert-myths’ like this one? Also, with a range of only 2 apparently ‘diverse’ styles of chicken their product isn’t even very diverse. 2 types of chicken is still only–using their own analogy–just black and white.

Herman Wasserman (@hwasser): I think there are various issues here that have become conflated in the somewhat predictable public outcry against ‘censorship’.

For one, there is the feeble attempt at humour that falls flat. I also find the ad unfunny–as a joke, the ad does not quite gel, perhaps because it takes itself too seriously. Then there is the ideology–problematic to say the least. The ad flattens out history, denies any possibility of asymmetrical distribution of visibility among competing cultural identities, and ignores the relationship between ethnicity and political and economic power. “We are all just foreigners here,” it tries to say, “so don’t come and make any claims to restitution or redress. If those people in Alexandra could just learn to laugh at themselves, they wouldn’t have gone and burnt immigrants alive.” But the lack of humour and problematic ideology aside, I do think the refusal to screen it was misguided. The SABC’s claim that it had ‘xenophobic undertones’ missed the point. It was meant to look like xenophobia, not hidden away underneath, but so exaggerated that the very possibility of xenophobia becomes impossible. By refusing to screen it, the TV channels bought into the current discourse about ‘media freedom under attack’ and lent gravitas to an ad that wouldn’t have attracted half the attention it has if it were allowed to disappear among the many other mediocre ads on television.

Mikko Kapanen (@mikmikko): Nando’s has always presented a moral conundrum to me: I like their vegetarian burger, but find their advertising very off-putting and this advert is perfectly in line with their TV advertising strategy. It has got practically no connection to the product they are selling, millions of Rands [the local currency] have been thrown into its production and it’s offensive. I am not even one of those people who are looking around for things to be offended by, but this just is. Just like probably every advert by Nando’s I have ever seen. I think textually these visuals have been analysed spot on here by others (empty-land etc.), but purely from a production point of view, I’d say that even in general this is a very typical South African TV advert. The advertising industry–having observed it in action especially in Cape Town–is very detached from the majority of South Africans, but they are too proud, stubborn or just unaware to admit it. I remember a friend who is an industry insider telling me how his white supervisor had told him with no irony or regret that in advertising “white is aspirational” and as a logical consequence of that they didn’t have to understand the Black cultures of South Africa while coming up with adverts to them. Many industry people also focus so hard on trying to win the TV Laurie (advertising award) meanwhile most radio adverts are pretty terrible regardless of the relative efficiency of that medium. No other country I have ever lived in has had such abundance of locally produced expensive looking TV adverts that effortfully try to connect the product and its potential consumers–and Nando’s is just one of the companies that have climbed on this ox-wagon.

Brett Davidson (@brettdav): Of course I’m sure that as long as people are discussing the ad, whether positively or negatively, Nando’s is happy.

Herman Wasserman: Yes, Brett, Nando’s might even be happier with the ad being ‘censored’ and gaining credibility online than having it screened on TV. But does this whole saga not also point to a certain failure of mainstream media, commercial or public, to engage their audiences in an informative, creative and entertaining manner in debates about race, culture and power? When these issues enter media debates, it is often done in such heavy-handed manner that audiences become fatigued and then the repressed racial tensions in those dreadful comments at the bottom of online news stories that we see everyday on South African based websites.

Lily Saint (@lollipopsantos): The manner by which people are eliminated (by a puff of smoke) is pure euphemism. Meant, I suppose, to recall various moments in South African history when different groups featured in the ad were targets and victims of brute violence, would the ad still have any claim to humor if people were shot dead by bullets instead of lamely evaporated into clouds of smoke? While there is certainly offense to be taken in the stereotypes and exclusions in this ad, the real problem as others have pointed out, is the erasure of actual histories of violence that continue to plague the present. By making light of these the ad wants to make consumerism the only identity that can unify people–the pun on “real South Africans love diversity” of course evokes national, ethnic and racial diversity, but more ominously speaks to the rhetoric of “choice” allowing us all to think we are free agents while keeping us spoon-fed capitalism.

Melissa Levin: On Brett’s earlier point. He is spot on. There is something important to be said about the multiple ways in which public space is increasingly privatized. Whether it is football teams that are owned by big business rather than supporters, or public parks that are sponsored by private companies, whether it is the roll-back of basic state services that are doled out to the well-connected or whatever. In this case it is a business that sells its product by both defining and giving meaning to the issues of the day. So public space is increasingly occupied by corporate soundbites. At the apparent end of history, social issues are addressed through buying a bag to end hunger, for instance, or eating ‘anti-xenophobic’ chicken. I cannot help myself but to carry on yelling about this and giving the chicken people more air-time, because I am all for the post-Nazi adage that suggests that the imperative of humanity is to be at home nowhere. That way, we make no claims above another. I am against the trite evocation of this theme that reinforces the politics of difference and the political imperative of being nice. The dominant exposition of the idea of culture transfers an idea of a categorical, immutable, static identity from the notion of race which we must no longer have an appetite for. But the claims are similar. Someone else has spoken of this process of trading race for culture as being neo-racist.

Kathryn Mathers: This discussion keeps making me think back to those SAB (the now multinational South African Breweries) adverts from the 1980s [and through the 1990s], you know, the perfect embodiments of South African cosmopolitan masculinity both black and white getting together in a bar for beer? I am pretty sure it was the 80s because I remember discussions about how they were filmed when black and white couldn’t drink in the same bar and how technology was used to paste together two separate but equal (sic) scenes. (There are also the post-apartheid versions like the Klippies “eish/met ys” romance.) I have always found those advertisements confusing since they were certainly utopic if you believed in a nonracial South Africa but they could not have been simply aspirational since it seemed pretty clear that the majority of potential SAB drinkers did not aspire to a nonracial South Africa. This discussion is making me wonder how these two advertisements are part of a long tradition in South African media that has less to do with erasure of violence past and present than with its displacement. By shifting the terms of racism/xenophobia rather than trying to erase them, which would be near to impossible, it makes it much easier to live with, making viewers/participants doubly implicated ultimately not just for the violence but for trying to hide it in plain site. I argue that this is a gesture typical of romanticized images of Africa in the US where the white savior is made possible not by the erasure of Africans but by their relegation to a backdrop or by the kind of move that Disney’s Animal Kingdom makes, which is not to ignore the social/political challenges of the continent but to bring one of the less disturbing ones forward, big game poaching, even in the context of an amusement park. Nando’s does not try to suggest that South Africans are not xenophobic–rather they show how everybody is xenophobic but we can still laugh about it so it doesn’t really matter, thereby displacing the problem without denying it, and making it even more invisible than erasure would or could.

Tom Devriendt (@telamigo): The male voice-over is the “Voice of Reason,” holding the moral high ground: “This is your history. History is not how you live it.” Reason trumps experience. The advertising genius trumps the consumer. But a stereotypical hypocrite is hard to visualize in a one-second shot. So the soutpiel, not for the first time, is let off the hook. There’s no time for self-criticism in the ad world.

Herman Wasserman: Good point, Tom. Perhaps this points to the invisibility of white South African English normativity and supposed ideological neutrality.

Melissa Levin: To Tom and Herman, I thought the white couple in the fancy car that were referred to as Europeans are the souties? And ‘even the Afrikaner’ who disappears is clearly another category of identity.

Herman Wasserman: Melissa is right. Appropriately, the English white stereotypes in the ad are not in some ‘tribal’ gear but can fit in anywhere looking thoroughly modern as we know.

Tom Devriendt: That, or–how I read it–it is a generic reference to the tens of thousands Belgian, Dutch, German or English immigrants that have made South Africa their home over the last decade — “Bought this house in Clifton for a steal!”

New Media and Activism

Lukonga Lindunda

A couple of weeks back I had the privilege of being able to bring together a few of the leading lights in social media in eastern and southern Africa, for a discussion about the role of social media in health and rights activism. The panel formed part of a meeting titled OpenForum 2012 – Money, Power & Sex: The paradox of unequal growth. Organised by the Open Society Foundation for Southern Africa in collaboration with its sister Open Society Africa Foundations (OSIEA – Eastern Africa, OSF-South Africa and OSIWA – West Africa), the meeting brought together an eclectic mix of activists, academics, artists and policy-makers to talk about “the factors driving change on the continent and how these will influence the African democracy, development, human rights and governance agendas over the next decade” – to quote the conference programme. (Full disclosure – I work for the Open Society Foundations, in its Public Health Program.)

The social media panel consisted of Rachel Gichinga, Kenyan blogger and the Co-Founder of Kuweni Serious; Elsie Eyakuze, a Tanzanian media and political analyst, columnist for the East African newspaper and blogger at the Mikocheni Report (highly recommended reading for lots more detail on the Open Forum); and Lukonga Lindunda, co-founder of the Bongo Hive in Lusaka – one of around 50 tech hubs on the continent. The discussion was moderated by activist Paula Akugizibwe.

In bringing these folks together I was interested in hearing about the possibilities, tensions and challenges presented by social media. For example, how much it is used for policy advocacy versus simply applying technology to boost service provision, the potential for mobilization weighed against the dangers of increased surveillance; the dangers of over-exposure and violations of privacy.

Rachel Gichinga

What struck me was that each of the participants – each of them new media innovators – emphasized the limitations of working in the online space in their countries, given the small percentages of people with online access (despite the expansion of mobile technology). For example, Gichinga, creator of a platform focused on energizing young, middle-class Kenyans as social and political change-makers, insisted that “you can’t work online without also working offline” and that for all the hype about African tech innovation, the number of genuine online participants remains low. “You don’t start the conversation in the online space,” she said, although “you can continue it there.” She said those working in the social media sphere need to apply a lot more discipline and rigor if they really want to have lasting impact. Lindunda highlighted the proliferation of disparate small-scale donor-funded projects using mobile technology to help deliver services (such as m-health). All very exciting and innovative, but seldom taken to scale and usually ending abruptly as soon as the initial donors lose interest. Eyakuze also emphasized that in Tanzania online conversations are still limited to a tiny elite.

But despite these cautions, there was also a clear sense of some of the benefits and possibilities offered by online participation. Possibilities which are likely to increase as bandwidth opened up and costs continue to drop. While Lindunda could not point to a clear role for social media in political activism in Zambia yet, he has seen it being used to mobilise consumer boycotts of, of all things, a cellphone company. He also mentioned that a mobile app is under construction, to enable Zambians to read the draft constitution on their phones (inspired by the The Nigerian Constitution App).

Although Gichinga underlined the limitations of online activism, she still felt it was important – with many of those people who did take some sort of online action, often becoming increasingly politically involved. “I don’t know whether that so-called ‘slactivism’ exists,” she said.

Elsie Eyakuze

Elsie Eyakuze felt that even in the still constricted Tanzanian context, “social media can be used in a mind-boggling number of ways.” For example, activists sometimes use Twitter as part of a ‘buddy system’: tweeting to their networks if they have been arrested – mobilizing support and ensuring they don’t just disappear into the system. Of course as much as activists and marginalized groups can use social media for organizing and solidarity, the state can also use it for surveillance and control.

Eyakuze said a number of the younger MPs and Ministers are on Twitter, and this creates the possibility for direct contact with citizens. And she herself also uses social media to test and push the limits of free expression in Tanzania.

June 7, 2012

Mutua Matheka and the Cityscapes of Nairobi

Mutua Matheka is a young Kenyan photographer who has taken it upon himself to re-visualize the city of Nairobi through the lens of the camera. To him, Nairobi has been ill abused by contemporary photographers who have only ventured to show it through the worst depictions of itself, its growing poverty, slums, and eroded infrastructure, “All we have are pictures that do not do the city any good and people, used to seeing them every day, start believing that that is all Nairobi has to offer” (Daily Nation). And this is the platform on which Matheka’s work stands. He has taken hold of the idea that photography extends beyond mere aesthetics, and can even shape and affect our own sense of self. His aim is to instil in Kenyans, and eventually all Africans, pride in their cities and pride in their place within them.

Matheka’s photography of Nairobi’s urban-scape envisions the city on both approximations of scale: the very minute and detailed versus the monolithic and sprawling, the latter a visual testament to its thriving, absent populace. His focus on light, both soft morning glows and, the more striking, vibrant pulsations of night capture the city’s various moods, energies, and activities that correspond to its inhabitants. While his signature twinkling night lights act as beacons of the metropolis, and signals of industry.

However, the presence of digital remastering within Matheka’s work complicates the reading of his images. With the introduction of digital manipulation, Roland Barthes’s idea (read: Camera Lucida) that the photograph marks an irrefutable place in time becomes more malleable. In Geoffrey Batchen’s estimate, “Digital images are in time, but not of time.” Thus Matheka’s photographs, while marking the historical (now contemporary) presence of Nairobi, they do so beyond the realm of objective reality. Shirley Jordan brings our attention to Regis Durand’s criticisms of ‘photographic excess’ in urban depictions. Photographic excess is brought on by “ocular experiments, which puncture our idea of the real and do violence to any simple idea of representation.” Matheka’s panoramas of Nairobi’s skyline, reworked in Photoshop to provide the viewer with an impossible 200° view, and taken from improbable vantage points, strip away human scale and puncture reality. His wide angles, depth of recession, and focus on the monumentality of his subject dissolve any sense of individual connection with his photographs of the urban sprawl. Additionally, many of his skylines are shot through with irresistible saturations of color, which further numb our senses to nature’s often more muted palette.

Matheka himself notes that this violence is done not only to the viewer, but to the cities, when their images become distorted by photographers, “You look at Paris, New York and Dubai and you just want to visit them, but when you get there, of course they are nowhere close to the pictures you saw.” And yet, it seems that Matheka is trying to force Nairobi into visually conforming to these contrived idealizations found in pictures of New York, Paris, Dubai, and thus to what Rem Koolhaas coined the uniquely, familiar “Junkspace” of the postmodern city. Is this the direction artists should be merrily marching towards — a consensual urban ideal?

For Matheka, it seems the answer is yes. In essence, Matheka’s art is reaching for the future by manipulating the present. He is orchestrating a relationship between what is and what can be in the creation of his urban-scapes. For him this opens up the door to “change the mentality of those living in these cities because if people believe they live in this bad place, you cannot motivate them to make it better.” His work leaves behind present realities for the tantalizingly benefits the future holds in the wake of globalization. And in doing so, maybe, people have something visual to hold onto in their minds eye, and something concrete to hang on their walls. But if he fails, it is because, despite his photographs’ commanding presence, the viewer cannot locate his/her place within them.

June 6, 2012

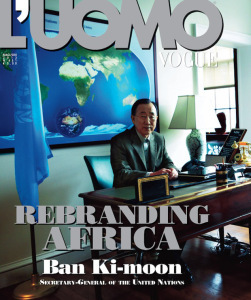

Vogue Italia’s “Rebranding Africa” disaster

Everybody’s trying to rebrand Africa, and it isn’t going so well. Vogue Italia’s latest issue — boosted by great billowing gusts of editorial hot air from both the New York Times and the Guardian — is called “Rebranding Africa”, and as you’d expect the whole thing is an embarrassing and insulting shambles. The images are okay, but otherwise it feels like something a middle-schooler cobbled together for a class project. And then got a “D” for it.

First: you’re re-branding the continent of Africa — as one does — so who do you pick as your cover star? Well, it was the obvious choice. What self-inflating fashion magazine wouldn’t lead their Africa edition with a picture of a South Korean diplomat sitting behind a desk in Manhattan? That’s right, people. The new face of Africa is none other than UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon. There are so many way to read this choice. An obvious take is that Vogue Italia, despite their claims of “rebranding” Africa must have decided Africans can’t govern themselves and need UN intervention.

The interview with Ban is very curious reading indeed. Apparently, the man is just world class at regurgitating very precise development statistics. It reads like an annual report of a large multinational NGO. Either that, or what we’re reading is a mashed up press release or a stilted email exchange dressed up as a conversation that actually took place (the latter is most likely the case). He drones endlessly on about the Millennium Development Goals, which is exactly what you’d expect him to do, but is also precisely the opposite of the kind of thing which invites the readers of Vogue Italia to think of Africa in a new way. With Ban Ki-Moon as its new face, Africa is (a) boring and uncool, and (b) a stubborn problem to be managed by foreign technocrats. No change there.

So why is he on the cover? We have absolutely no idea. The man dresses like any other boring technocrat. The Guardian said the Vogue Italia coverage showed that the effort to rebrand the continent “wasn’t just a token effort” and that it made us (in the West, naturally) sit up and take notice. How? To us, all that this shows is that the addled people at Vogue Italia are incredibly unimaginative, and quite weird when it comes to its coverage of the unfamiliar — that is, the dark continent/country of Africa.

One guy they could have picked instead for the cover is Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan, whose moribund interview with chief editor Franca Sozzani really ought to be somehow preserved in formaldehyde and wheeled out at journalism school graduations as a chilling example of just how bad journalism can get. Much of the copy is taken up with Sozzani’s worrying whether they can photograph Goodluck the Vogue way.

The “interview” is really long passages of Sozzani generously offering her explanation to Jonathan of exactly what is wrong with Nigeria:

All the richest Nigerians spend their money abroad because there a no shops here, no hotels with a chic African flair, no hip restaurants or clubs. Why not build an African Rodeo Drive in Lagos or Abuja, with boutiques carrying both imported and Nigerian goods?

Finally, there’s a single lonely quote from Jonathan in there, in which he agrees with the long speech Sozzani has made. It’s not often we feel sorry for Goodluck Jonathan, but seriously, poor chap. It also not sure when they did the interview. There’s no word of #OccupyNigeria, which showed Jonathan up to be insensitive and dithering.

You also get the sense that the next time Vogue Italia “do” Africa, Nigeria’s notoriously corrupt and terrifyingly incompetent oil minister will probably be the new cover star, as Sozzani drools mindlessly over one of Nigeria’s most detested politicians:

We are joined by the Minister of Petroleum Resources, Diezani Alison-Madueke, a gorgeous and elegant woman – who also happens to be a princess – dressed in traditional robes, with a Master’s from Cambridge and the distinction of being the first woman to run Nigeria’s most important ministry.

Actually they did already. In the same issue.

Sozzani’s representation of Nigeria’s complex social and political situation is as astute as you’d expect it to be, and thanks to the internet, she gets called out big-style by a Nigerian called “Rachel”, whose comment on the website is by far the best piece of writing in the entire magazine, print or online:

“This is possibly this worst piece of journalism on Nigeria I have EVER read. I cannot tell you how angry people are reading this. It is a shallow piece of vanity which glosses over the complexities of the tensions in Nigeria. When you say ‘Muslim’s ultimatum to the Christians’ – do you mean that all the Muslims who make up half of the 158 million people living in Nigeria have a vendetta against Christians? WHAT ARE YOU TALKING ABOUT???? It was Boko Haram’s ultimatum – you can’t just say ‘Muslims’ throwing in millions of people into a sentence who have felt just as much violence and suffering as Christians in Nigeria. It isn’t just Christians who have died during the violence but many Muslims. Sweeping statements like this fuel tensions between Christians and Muslims but of course that is perfect for the American audience who probably believe every Muslim is part of Al Q’aeda.

Your dramatic entrance to Nigeria was completely unnecessary. There are thousands of expats who have lived here for years in complete safety. It is reports like this that do nothing for the country. Do not flatter yourself to believe that you would be of ANY value to a terrorist. You would probably annoy the hell out of them. WHY did the editors think it would be important for readers to hear what you think what should be done in Nigeria? You were talking to the President of the country who is dealing with increasing rates of poverty and a decline in security and you are telling him to build an African Rodeo Drive? Oh yes, please build it so the 5% of the super wealthy population that can actually afford to buy from these sort of shops will no longer travel. The rest of the population can look on with their begging bowls in envy.

And also – the Petroleum Minister is probably one of the most corrupt people in Nigeria who has only added to the poverty, and therefore the security problems in the country. Don’t you know ANYTHING about the fuel subsidy scandal here? Do you know how many people are calling for her resignation? I feel so disappointed. I dread to think what the issue is like. I agree with you on one thing, it is important that people see beyond the famine and death in Africa and see the potential it has to grow but the potential has to be found in communities who are doing what they can to get out of poverty whether it be telecommunications to do banking, solar energy to power their small businesses or community initiatives to support women. What use is a Banana fricking Republic?”

Sozzani responded with this rather bitchy outburst:

“@Rachel: It’s been a long timesince I last received such an idiot comment on my website. When I say Muslims, I never thought that the entire population of muslims is against Catholics as I live part of my life in Morocco and all my friends there are Muslims. I think that you took the negative side of the article and I’m sorry to say that is you who is against your own country, not me, as if we give work to women and we build up new shops and hotels, even for the 5% of the population, it can attract tourism and give job to local people. Is this nothing for you? Is it so unnecessary that I go to see them and try to help them?Iif so, I’m sorry for you, you don’t love your country and don’t want to help it. I don’t care and I go on my own way and certainly you won’t stop me. Just for yuor info, all the people – young designers, tailors and those producing fashion – are very happy and selling well thanks to me. This is the most important thing for me.” [sic]

Blimey. It’s a close one, but I think overall we’re with Rachel on this.

Other than that there’s a short piece on El Anatsui which wrongly says he works in Ghana and then miraculously manages to rebrand (why not?) his transcendent genius as yet more developmental gobbledygook:

Forerunner of a big part of the continent’s contemporary art, with his artwork he has shown how a possible solution for his country is that of believing in the concept of recycling as a source of creativity and richness.

Some bearable features on African footballers in Italy and Didier Drogba, they discover Nollywood again (The New York Times has done so too recently), the formerly disgraced Kenyan TV journalist Jeff Koinange (whose style is something to behold), that country’s Prime Minister Raila Odinga, Swedish-Ethiopian chef Marcus Samuelson (there are other top African chefs Vogue Italia), a picture of the Rwandan Ambassador to Britain handing his credentials to Queen Elizabeth II who is dressed in what resembles a nightgown, more Presidents, and a few models.

And then there’s Tommy Hilfiger, who gets some great free advertising with an African alibi as the magazine reproduces yet another long, unreadable press release. An unattributed quote explains how the mostly boring fashion scenster Hilfiger is basically the new Jesus Christ:

When Tommy Hilfiger came to the village for the first time, no one knew who he was. But when locals realized how famous he was in the rest to the world, they were very impressed: they were satisfied that if someone so important, rich and privileged could be interested in them and spend time with them, they themselves counted more than what they had been led to believe. They began to have more faith in the possibility of change”.

Well, Africa, consider yourself rebranded.

Sodade

By Olufemi Terry

Saudade. European Portuguese: [sɐwˈðaðɨ], Brazilian Portuguese: [sawˈdadʒi], Galician: [sawˈðaðe]; a deep emotional state of nostalgic longing for an absent something or someone one loves, often carrying a repressed knowledge that the object of longing might never return; related to the feelings of longing, yearning; vague and constant desire for something that does not and probably cannot exist; a turning towards the past or towards the future.

He’s learned the word from songs that invoke Brazil, Sao Tome, Angola. Bonga’s version, the voice gruff yet plaintive, is preferable to Cesaria Evora’s; and there’s a fitting bittersweetness in the knowledge that Bonga was Savimbi’s man.

Meaning is elusive, but in Cape Verde, he hopes to locate the very roots of sodade. The elements are here on these islands: geographic isolation, a strain of the melancholic Lusitanian blood. Also history’s cruelty: enslavement, drought, diaspora.

He recognizes the season—Harmattan—the instant he enters Boa Vista’s small hangar of an airport: the gusts of chill wind, in spite of which dust hangs unmoving in the air; and the flat and far-off whiteness of the forenoon sun. From a tinny unseen radio, kizomba is playing.

Boa Vista is an unanticipated echo of half-forgotten cities: St George, Grenada; Bo-Kaap; Hargeisa. In sudden moments, it might even be Lamu. The island, its main town, Sal Rei, the creole inhabitants, all these are palimpsests of the slave trade even if the arid landscape bears none of the usual characteristics; there are neither cotton plantations nor cane fields. Cape Verde, like Cape Town, served for a way station; a broodhouse for chattel, a purgatory.

Sal Rei drowses but the air is feverish with tourist development, with migrants from Italy, Senegal, Spain. Most of the corner shops, the lojas, are in the hands of mainland Chinese.

He slips without difficulty into a routine, placing cultural distance between himself and the European package tourists. He rises each morning, leaves the rented, bare flat and trudges over dunes to buy food in town. North, across a strait of the Atlantic, is an uninhabited isle, a spit of paler sand on which the sun always seems to be shining. From Sal Rei’s sole bakery he buys bread of a familiar, nutritionally useless sort, made from overmilled white flour and flavored with cinnamon or custard.

In the fish market it is, for him, always 2 o’clock: sea light pouring in onto the steel surfaces so that they throw off an unendurable glare; the boats have just moored at the dock and fishwives are setting to work with flensing knives.

One moonless night, he stands over the sea on an open gazebo, listening to irresistible violin music: mazurkas, mornas, coladeiras; medieval folk rhythms of Mitteleuropa, itself provincial and hardscrabble, that have long since infiltrated this remoteness via the old country, Portugal. Conversation with the stranger in his arms is out of the question. So long as he says nothing he’s able to pass for a local. During two months whenever it comes out that he’s in fact not Caboverdianu and speaks no Kriolo, he receives looks of suspicion rather than surprise.

In rituals and in wanderings though the wreck of half-built tourist apartments, he perceives ironies that are like glimpses of sodade: the dark-skinned men with the lowly, futile job of standing guard are Bissauans, economic migrants but heirs also of the revolutionaries that freed Cape Verde from Salazar. News comes that the airport in the capital city, Praia, is to be renamed for Nelson Mandela, a decision that strikes him as expiation for the quiet collusions of the past. And on the night of the African Cup of Nations final, he hunts for a bar in which to watch but no one is interested, or even aware. He makes do, at last, with Portuguese football via Satellite: lowly Guimaraes vs. Setubal.

The dead from other islands, someone, an acquaintance, tells him, were formerly brought here to Boa Vista in ships for burial. This bit of apocrypha, for which he finds neither refutation nor evidence, is offered as a reason for Boa Vista’s “strange madness.” At the end of two months, after visits to other islands, he’s decided Boa Vista is the Germany of Cape Verde. Its people are reserved, even stoic; the tourist economy is comparatively strong, unemployment is low.

In the space of a decade, modernity has slipped over Cape Verde like an opaque, close-fitting skin. Its effect on this secluded, endogamous people has been one of re-syncretisation. This is not Africa, he’s told in Sao Vicente, the second-largest island. “It’s Europe.” Listening, he thinks: here are creoles flaunting their inheritance: an instinctual ambivalence (or is it complacence?) toward Africa he’s observed in the Antilles, in Cape Town, also in himself; middle-aged men exercise a slaver’s droit de seigneur over comely young women; and there is the near-imperceptible influence of hair texture and skin tone.

His arrival on the small island of Sao Nicolau coincides with the start of Carnaval. For three days Sao Nicolauenses crowd the capital’s floodlit main praca. Bacchanalia is raucous but restrained; there are no naked, oiled bodies. Ringing the praca are several Chinese lojas which remain open late into the night, after other businesses are shuttered. The proprietors venture out now and again to observe the spectacle, and, to his helplessly exoticizing eye, their faces betray bemusement. Is there any cognate in Mandarin for sodade?

The island’s two Carnaval bands have each composed two songs. After thirty-six hours, in which the bands alternate, the music has become tiresome. He’s content when the fête has ended and he can sit typing notes beneath the benevolent stone gaze of Baltasar Lopes, the father of Cape Verdean letters. The cobbles are swiftly cleared of broken glass. At the edge of town, papier-mâché Carnaval floats lie discarded like straw dogs.

And a Lenten hangover now descends on Ribeira Brava, which, with its statues and gardens intimate as bowers, resembles a 19th century Portuguese country town. As light fails, a listlessness indistinguishable from desperation shows itself in the faces of the Bravenses. Every night is the same—a little death—and his own pleasure at the town’s charm and languor is tempered. Life in the mountain crevasses above may be more trying than here in town but neither existence offers much stimulation. Remittances and the packages of Nikes and iPhones sent by relations in Rotterdam and Brockton, Massachusetts have made of Sao Nicolau an existential limbo conducive to creeping, fretful madness. The wait from one carnaval to the next goes by at a trickle.

‘Sodade’ is part of a more extensive mixed media project, ‘A creole odyssey’. Read Olufemi Terry’s previous contribution here.

Safe House

In February, a reporter for DIY, a London based culture and style magazine, sat down at a press junket with Denzel Washington, star and executive producer of the big budget spy thriller ‘Safe House’ (the film came out on DVD this week). Over the course of the interview, the reporter asked Washington how involved he had been in choosing the films shooting location and setting—Cape Town, South Africa. The actor answered, “None. I think it was originally supposed to be Buenos Aires? Rio! … Daniel [Espinosa, the director] went to South Africa, and he liked South Africa, and that was it. I think it was the right choice. I think just practically, aside from the look and all that, for my character’s perspective, it was going to be easier for me to blend in, in a “black” country than in a “brown” country.”

As a friend and I exited the theater on 19th Street in Manhattan back in February after seeing ‘Safe House’, which co-stars Ryan Reynolds, we discussed the discontinuity in what the American audiences think of as Africa and South Africa in particular—what was largely displayed on screen was anything but South Africa. Instead, the Cape Town of the film, where most of the action takes place, has a generic diversity to it. It resembled something closer to a side of an unnamed North African or Middle Eastern city. Other scenes suggested that bits of Rio, Istanbul and Cairo had been cut and pasted together to create a completely new city.

Filmed in the vein of the ‘Bourne’ movies, the director’s camera movements simulate the violence they portray, this along with the close-up fight scenes aid the overall feel of the story as a gritty spy thriller; Washington, a supposedly traitorous CIA agent plays a game of cat and mouse with Reynolds as the under-experienced, good-guy agent. Though certainly a better-than-average action movie, some reviewers were critical of Espinosa’s style, which is notorious for making terrible use of locations; ‘Safe House’ was certainly no exception. “Espinosa’s shaky, kinetic camera is a familiar action movie trope by now, but rarely has it been accompanied by such a lack of geography,” explains Katey Rich on CinemaBlend.

Early on in the film, Washington, fleeing from unnamed bad guys—of Middle Eastern descent, another recognizable Western trope—runs into a crowd of protesters (with placards demanding jobs), but they are anything but the conceptualized black countrymen the actor makes reference to. Surrounded by the young and overwhelmingly white assembly, this looked more like a scene from an early Occupy Wall Street event, since unemployment is hardly a problem for young white people in South Africa. And Washington is far from blending—with his ragged Cornel West hair, standing a few inches taller than everyone around him, Washington stands out like a sore thumb.

Early on in the film, Washington, fleeing from unnamed bad guys—of Middle Eastern descent, another recognizable Western trope—runs into a crowd of protesters (with placards demanding jobs), but they are anything but the conceptualized black countrymen the actor makes reference to. Surrounded by the young and overwhelmingly white assembly, this looked more like a scene from an early Occupy Wall Street event, since unemployment is hardly a problem for young white people in South Africa. And Washington is far from blending—with his ragged Cornel West hair, standing a few inches taller than everyone around him, Washington stands out like a sore thumb.

But we should not be surprised at these casting decisions.

AIAC has posted previously about the transformation of Cape Town into a fictional landscape, able to play the role of such locations as modern day Seattle, Civil War era Gettysburg, and L.A. circa 1930. Sean wrote back in January that not surprisingly the booming international film industry growing in Cape Town contributes “to the racial political economy of the city. There’s lots of work for mostly local and expatriate whites as actors, models and extras in front of cameras. Blacks, with few exceptions, it seems do lots of the heavy labor in the industry.”

When Washington finally meets black people, he travels to Langa, a black “township” just outside the old city center, to meet a go-to man—who can get you everything from fake IDs to copies of hacked government databases—in order to obtain a fake passport. Apart from the strange plotline of a Salvadoran hacker living in a black township in Cape Town with unlimited internet access—any visitor to South Africa will point out the dismal internet situation there, despite all the hype—said black township is depicted as just one vast slum.

The majority of audiences rarely see past guise of set dressing into the political and racial implications of not only the film but also of the film industry itself. Western audiences remain content with Hollywood’s constructed perceptions of both countries and cultures outside of their own, when in reality the differences stick out almost as much as Denzel Washington in a “brown” country.

June 3, 2012

Village Portraits

Wim De Schamphelaere’s ‘Village Portraits’, often made out of more than 700 different shots, are printed on meters wide photographs and displayed at galleries in Europe. The photographer prides himself on returning to the (African) villages where he took those portraits — and where the first reaction usually is “to cut them up and divide the different parts among the ones portrayed”.

De Schamphelaere’s panoramas are really gorgeous, exploring the linkages of families and familiarities in close-knit communities where there is a sort of “calling out” to each other through signals sent by physical stature, facial features, clothing, ways of standing and arranging oneself. We also see that smiling for the camera, a trope that only came to be common in the West as photography became faster, and more ubiquitous (and therefore, not a solemn occasion to comport oneself for a portrait), and when one’s teeth were expensively cared for (see the gloriously irreverent A Brief History of the Smile by Angus Trumble). When there’s a slightly odd-man-out, we see that difference immediately, too, even though these are not our own people; and yet, we also see that he, too, is embraced and included (hilariously, this inclusion/exclusion reminds me of Southpark episodes).

And we also get to see a certain picturesque diversity in what and who constitutes an “African village.” It is the kind of thing one would want to have hanging above one’s settee, or in the headquarters of your NGO’s office.

For the photographer’s part, we can comprehend that he feels a wonderful connection to the people he photographs, who must bestow upon him a great deal of love. And yes, of course we understand that the people in those villages want to get copies of ‘their’ picture. They are poor, and will not have many chances to see themselves in print. And a powerful white figure from another world arrives with his magical, expensive equipment, including them in his generosity — what’s not to like?

The images are striking: quite beautiful, quite poor, quite “villager/other”. But if the purpose of making images of the other is to create intimate links of familiarity, and share with them one’s own ways of seeing self and other, why display the images in the west? If the purpose is to give the photographed people a way to see themselves as beautiful, as photographers of otherness often claim, then De Schamphelaere might think about limiting himself to giving those very subjects a copy. To display them — with all the connotations of poverty, the hovel-quality, and the dirtyness that those of us who live outside of that existence (such as a gallery-goer in Europe) will undoubtedly assign — simply reifies that otherness and difference. I’m not saying that we must all pretend that poverty, grass-hut dwelling, and otherness does not exist. Nor am I saying that it is impossible to look beyond our frames of reference and see people who are simply living their lives without National Geographic-ing them. But why display it all, and why stare at this?

June 2, 2012

Cannes is a Country

Another May, another champagne drenched Cannes festival. Soaked in the Riviera sun, there were a few interesting films screening from outside of Europe, some of which caught my attention. First, a film from veteran Senegalese director Moussa Toure (not the footballer). His film, ‘La Pirogue’ screened in the Un Certain Regard section of the festival, and stars Bassirou Diakhate and Moctar Diop:

The film follows the story of 40 men who try to make an illegal crossing from Dakar to the Spanish coast. Many of the men have never seen the sea, or know what to expect upon their arrival to Europe. (Three more fragments of the film here, here and here.)

About his inspiration for the film, Toure says:

You know, there are subjects that you don’t go looking for, they’re just there, right in front of you. When I open my window, we’re by the sea. In Dakar we’re not by the ocean, we’re in the ocean. We can see the sea on both sides and people leave in pirogues from both sides. Leaving by pirogue is easy, but what is it that makes them leave?

From the view of the yacht-riddled Riviera bay, the contrast to ‘La Pirogue’ could not be more striking. By taking on the subject matter of illegal crossings and the risks that migrants take on treacherous water crossing, Toure’s film links to a tide of others released recently that address this subject matter, a few of which we mentioned here. It also somewhat morbidly chimes with the recent international outrage about the ‘left to die’ boat, abandoned and ignored by NATO forces. The film did not secure distribution at the festival, but perhaps we can hope that it will soon.

Next, another Senegalese director, Alain Gomis, whose film ‘Aujourd’hui’ (‘Today’) gained distribution from its screening at the festival, also screened at the Berlinale earlier in the year, which we wrote about here.

Gomis describes the film as “the kind of tale that takes place in an imaginary society in which death comes looking for someone. The film starts when he opens his eyes and ends when they close.”

A still from ‘Aujourd’hui’

Also screening as part of the Official Selection was Nabil Ayouch’s ‘Les Chevaux De Dieu’ (‘God’s Horses’), a film about the 2003 Casablanca bombings, a film The Hollywood Reporter described as an ‘intimate portrait of boys growing up in a toxic environment’. Written by Jamal Belmahi, the film is based on a book about the five simultaneous explosions in Casablanca in 2001, and “uses current events — the death of King Hassan II, the attack on the World Trade Center — to explain how dwellers in the Sidi Moumen slum slowly turned towards keeping women at home and tolerating, when not embracing, the rise of fundamentalism.” Trailer below (only with French subtitles):

Next, a film that has divided critics with its uncomfortable subject matter — sex tourism in Kenya. ‘Paradise: Love’ screened in competition at this year’s festival, directed by Ulrich Seidl. Anyone who has travelled to Kenya will recognize the scenes depicted, so it almost falls into a caricature of itself. Yet the delicate, vulnerable side of white women looking for sex with ‘beach boys’ is a side to prostitution that critics seem to, as yet, be uncomfortable with.

Here is the trailer:

And three more fragments here, here and here. A synopsis: “sugar mamas” = European women who seek out African boys selling love to earn a living. Teresa, a 50-year-old Austrian woman, travels to this vacation paradise.

Finally, also in Cannes but away from the cameras, Kivu Ruhorahoza presented his plans for his second feature film ‘Jomo’ (you remember we loved his ‘Grey Matter’) in which “Jomo, a young gay Kenyan man named after Jomo Kenyatta, the father of Kenyan independence, gets deported from London after ten years spent in the United Kingdom. His arrival coincides with that of famous American televangelist Rev. Stanley Renge who is organizing a month-long “I Want You for Heaven!” Christian campaign. Meanwhile, men from a Washington-based organization are busy meeting high profile local politicians.” Promising stuff.

June 1, 2012

Friday Music Break

I’m taking over the Friday music break this week. First up, the prolific Azonto producer E.L. surprises us this week with a 25 track debut album. He had so many songs stored up he decided to release a video for one that’s not even on the album. Check his Swagga.

The Very Best drink some magic juice in Northern Kenya.

Kanye and Jay Z team up with Romain Gavras who capitalizes on images of our global instability. Will marrying Hip Hop with riot chic help out Angolan protesters? Probably not.

In video that is a little more grounded than your average commercial Hip Hop video (and especially contrasting with the one above), Nas, who’s collaborated with family members before, releases a song and video tribute to his daughter!

Trying to deliver on the promise to incorporate more Afro-Latino-ness on the blog, here’s Colombian Pacific Coast Hip Hop group Choquibtown’s latest “Hasta El Techo.”

And, Maga Bo’s “No Balanço da Canoa” featuring Rosângela Macedo and Marcelo Yuka. The remix album for his Quilombo do Futuro project dropped this week.

Nos vemos a primeira feira!

The African Diaspora in the Indian Ocean World

The online exhibition, The African Diaspora in the Indian Ocean World, put on by the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture provides an overview of the transit of East Africans into Diaspora communities within the Indian Ocean world, and their various settlements among Arabic, Indian, Persian and Asian communities. The exhibition draws from several collections within the Library’s holdings and from outside sources. It includes an array of medias, photography, illuminated manuscripts, drawings, prints, and watercolors. Omar H. Ali, Associate Professor of African American and Diaspora Studies, at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, was the consulting scholar and essayist.

Ali’s essays provide ample quantitative research into the movement of peoples due to the slave trade. His focus is on the historical transplantation of East Africans, and he documents their social statuses and the lives they led within their new Diaspora communities. Ali also highlights the lives and deeds of several prominent transplanted Africans, as well as touches on the modern day formations and realities of the Diaspora people. While Ali makes only passing references to the visual cultures of the Diaspora people, he does elaborate on several musical and performance contributions, such as the ‘tanburah’, a ritual performance “used for curing illnesses caused by spirit possession (‘zar’), for mourning the dead, or for celebrating weddings” that incorporates both music and dance.

Regrettably, most of the digitized drawings and photographs in the exhibition are pulled from European sources, which does not give the viewer a substantial picture of how Arabic, Indian, Persian and Asian populations’ visual culture incorporated and represented these diasporic populations. For this, you have to look to the pages taken from the illuminated manuscripts, within the NYPL’s collection there are the ‘Shâhnâmah’ and the ‘Siyar-i Nebi’, or to a selection of the color photographs for a contemporary view.

Despite the lack of coverage linking the visual cultures of East Africa and the regions surrounding the Indian Ocean, and the Diaspora communities therein, the visual ties between these cultures are quite strong. Architectural connections can be drawn between the images provided of the Sidi Said Mosque, built by the Ethiopian, Sidi Said in 1570-71 in Gujarat and the numerous rock-hewn churches in Tigre, Ethiopia, or perhaps better still the intricate lattice work in the arches of the Mosque and that within the metal and wooden hand and processional crosses of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Protective amulets in Ethiopian, Jewish and Islamic societies are a visually performative means of linking faith and visual culture. Magic scrolls from Ethiopian are a commonly employed protective amulet. These scrolls are written on vellum or paper, and often hung around the neck in leather cases. They are inscribed with protective prayers, powerful visual symbols, and spells that shield and aid the wearer from harm. (See Jacques Mercier’s Ethiopian Magic Scrolls for further reading.) In the Jewish tradition, ‘Tefillin’, scrolls inscribed with verses from the Torah stored in black leather boxes, are worn around the arms and forehead in order to physically remind Jews of their faith and to spiritually connect them to God’s words. And in the Islamic tradition miniature books or cases with verses of the Koran set within, often served as talismans, providing Divine protection in battle and in everyday life. (See also Heather Coffey’s ‘Between Amulet and Devotion: Islamic Miniature Books in the Lilly Library’.) Like ‘Tefillin’, these amulets, or ‘bazubands’, could be worn on the arm or hung around the neck, and in the Ottoman tradition even affixed to battle standards.

Contemporary visual parallels can be found in the colorful decorations on local public transportation vehicles. The above exhibition image titled, “A Sidi Family in Gujarat”, shows a family on a ‘chhakda’, or auto-rickshaw most similar to a ‘bajaji’ in Tanzania. The colorful designs on the chhakda match the spirit of the ‘matatu’ buses in Kenya and the ‘twegerane’ minibuses in Rwanda.

The resettlement of diasporic artisan communities throughout the Indian Ocean is one of the binding forces in the region’s linked visual cultures. Though further research is needed on this subject, Mark Horton (in his article ‘Craftspeople, Communities, and Commodities: Medieval Exchanges between Northwestern India and East Africa’), archaeologist at the University of Bristol, England provides one example of archaeological evidence for these relocated communities, “an African community living at Sharma on the southern Arabian coast around l000 AD, [is] evidenced by substantial proportions of African pottery. [...] Around 30 percent of the pottery is of African origin, quantities that cannot be explained through a trade in ceramic containers (most of the pottery is cooking pots) but must be an ethnic indicator of a resident African community.”

Overall this online exhibition provides a good historical entry point for familiarizing oneself with the historical trade, travel, and cultural intersections of the Indian Ocean world. But to truly appreciate the artists and art works of the region that depict these intersections, you must be able to see the art in person — the next step I hope for the Schomburg Center.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers