Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 530

June 19, 2012

The Very Best’s “Kondaine” and Village Beat’s advocacy

The musical group, The Very Best is a tandem between Malawian singer Esau Mwamwaya and London based producer Johan Hugo. Both met and live in London. AIAC has dedicated several posts to their music. From scanning a few of their videos, it seems they often poke light of the music video genre, taking playful measures with “Yoshua Alikuti,” which riffs off of Lil’ Wayne’s “A Milli” and “Warm Heart of Africa,” which makes use of the green screen to project ‘African’ scenes replete with two backup dancers familiar to homegrown music videos. The song, “Kondaine” released off of The Very Best’s new album MTMTMK, is no exception. It has The Very Best plus their guest singer, Nigerian-born Seye, travel to Northern Kenya, visit a witch doctor, drink Kondaine, and turn into goats. Pretty light hearted, except for the graphic goat scene, which, if not for the upbeat tone of the song, would fall more in line with a darker message. But wait, you may ask, why shoot your music video in Kenya?

Luckily the final seconds of the video answer that question: director’s choice. Both new singles off of MTMTMK were shot and directed in collaboration with the California activist arts based organization Village Beat. “Yoshua Alikuti” was shot in Nairobi, and “Kondaine” in Northern Kenya. Village Beat is active in both of these areas, currently filming a documentary on the plight of Kenyan street children in Nairobi, and working to raise funds for a music festival to increase awareness of the displacement of the Turkana people in Northern Kenya, and the controversy surrounding the building of the Gibe III Dam.

All well and good, but what does this music video addendum really do, besides act as a plug for Village Beat’s advocacy efforts? Let me lay it out below:

Love and respect to our Turkana friends of Epiding village in northern Kenya — particularly Matet & MC Maji Moto. Sacrifice and ceremony are traditional practices of the Turkana tribe used for events such as marriage, death and in our case, the welcoming of visitors. Drinking Kondaine — the magic potion — is not a traditional Turkana practice. Therefore, no members of The Very Best were actually turned into goats. To know more, visit www.villagebeat.org

With the exception of its guest extras’ shout-outs, all it does is call into question the music video even more. I generally don’t expect music videos to provide many hard truths, except what I learned from rap videos, that street living is rough. Now Village Beat wants to correct my “assumptions” about Turkana culture, as if I were in fact making any, and in the very last seconds have me reprocess this whole video in terms of reality, seeing it as inauthentic, instead of as a visually entertaining spoof on visiting a “witch doctor”. Now I have to think, why were the Turkana even highlighted in the first place if they have no relation to music’s subject matter? Oh right, because Village Beat wanted them to be.

But to close in Village Beat’s defense, if I were to have immediately coupled Kenyan rural life with a tradition of black magic, this addendum would provide me with a healthy dose of reality check: hey now, it’s just a music video.

June 18, 2012

Curating Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction

Currently showing at the Arnolfini, the exhibition ‘Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction’ brings together various fictions. Science fiction becomes racial fictions become state fictions that fold into colonial fictions and back again. Science fiction becomes an umbrella for a range of discourses that, with the distance of futurity, are exposed in all their strange power. A startling and witty symmetry is revealed through the chosen works of the exhibition. We blogged about the exhibition speculatively here, and I wrote a review of the show in the UK magazine, The Wire. For AIAC, I asked the two curators of the exhibition – Al Cameron and Nav Haq – to explain a bit more about their interest in these ideas, and how the exhibition came about.

What sparked your interest in science fictions of (and in) the African continent?

The starting point was noticing a specific tendency that seemed to be emerging in contemporary art, cinema, and wider culture, and thinking about how we could approach this within the context of an exhibition. In some ways, we also felt that this work was different to Afro-futurism, at least in its applied sense. In fact, though parallels can be made, we feel it is something that to some extent had emerged independently.

To us, Afro-futurism seemed to be a discourse about the (usually African American) diaspora’s participation in a technological futurism, as opposed to being tied to a sense of roots and tradition with which the European imaginary has daubed African-originated culture for its own purposes. That was a kind of machine-theory or a post-humanism – as you pointed out in your review of the exhibition in the Wire there was also an attempt to bypass the association of African origins with orality, which was manifested in multiple attempts to subtract the pure voice from late-20th century dub and techno, for example. A lot of the works in this exhibition – Omer Fast’s for example – place speech at the centre of their stories. In Neïl Beloufa’s film Kempinski (2006), the Malian characters inhabit the future through interviews in the present tense. Here, a series of voices that would normally be excluded from discourses on the future are made audible.

We believe that the works in our exhibition do something different in the broadest terms. In general, they place human desires, rather than technological futures, at the centre of their speculations. Technology appears in the works mainly as an oppressor.

The word superpower in the exhibition’s title goes against what most people would associate with Africa. Why did you choose this word?

We actually borrowed the title from Mark Aerial Waller’s installation film, Superpower – Dakar Chapter (2004), but clearly it indicates a shifted perspective. The idea of superpowers obviously references the science fictional idea that humans might have extra-terrestrial abilities, and in Beloufa’s film, where Malians are asked to imagine the future as if it was present reality, they propose things like telepathic communication and teleportation. Then again, the title performs a reversal of narratives and expectations about the global order of things. Throughout modernity and subsequent epochs, Africa has been subjected to the almost continual interference of outside states with the ability to project dominance beyond their borders, whilst finding those borders difficult and dangerous to cross in the other direction.

Through the three chambers of Omer Fast’s installation, Nostalgia (2009), the usual narratives about patterns of migration are disrupted, and a story about a West African immigrant’s experiences in the West is collapsed into a claustrophobic fantasy about Europeans seeking a better world in a retro-futuristic Africa. Kiluanji Kia Henda’s Icarus 13 (2010) imagines an Angolan mission to the sun – a ridiculously ambitious project, but one which the Luandan monuments already prompt. The tomb of António Agostinho Neto, Angola’s first president, was gifted by the USSR to Angola. Taking the form of a futurist spacecraft, ready on the launchpad for blast off, it promises an ambitious technological future for the fledgling Angolan state: the first mission to the sun, beyond the reach of our present superpowers. Yet, perhaps in its implausibility it cements the real historical dynamic of this future, one unevenly bequeathed by a superpower to its vassal state.

Of course, this fantastical scenario didn’t actually emerge – Neto’s socialist ambitions were dissolved in a quarter-century of civil war, while the USSR would over-extend its global reach and collapse its visions of collective prosperity. Both utopias burned up like Icarus who got too close to the sun. Only in Kia Henda’s speculative fiction does the improbable feat succeed. To extend this thinking, the sun itself has been mythologized throughout history as a supreme entity, or a superpower, with the power to burn up humans who come too close. Nevertheless, in Icarus 13, the attempt to make a claim on the future on behalf of an African state reverses the usual scenario wherein outside bodies, whether through global military power, politico-financial constraints like the “structural adjustment programmes”, or indeed through culture and media hegemonies, appropriate the right to describe the future.

A still from Beloufa’s film Kempinski

What, in the context of the collected artworks that form Superpower, is your understanding of science fiction?

Science fiction takes on many forms – it has offered experimental timespaces for testing alternative ideas and speculating on possible and probable trajectories, but equally, it describes, for example, a steady stream of mindless blockbusters which continue to trade on ossified expectations and lazy assumptions. We don’t profess to be experts in the genre, but in the context of this exhibition and the works shown, it seemed to offer a number of possibilities, especially in terms of how re-orientations of tense and folded notions of time might reconfigure our view of the present.

Perhaps the key activating principle it has in the context of this show is in the way it can produce complex diagrams of time. In general, although not exclusively, the genre is concerned with the intervention of possible futures into the present, like the light from distant stars on which Mark Aerial Waller’s film relies in a structural and narrative sense. Whether or not it imagines distant times or galaxies, SF is essentially always concerned with the present.

What seems particularly striking about the assembled works is their collective comment and critique on contemporary discourses about the African content, often accessed via the future… they critique colonialism, paternalism and the ‘white saviour complex’. Do you see this as the role of science fiction, as an important way of thinking about social realities?

In its most intriguing moment, Chris Marker and Alain Resnais’s anti-colonial film of 1953, Les Statues Meurient Aussi, introduced a science fictional element, when they state that “we are the Martians of Africa”. Although for them this reversed the typical Western ethnographic gaze at the Other, in a sense it also stated the obvious about colonial encounters. The West’s command that Africa submit to its rationalized, modernizing perspective already has something of science fiction about it – visitors from another world whose technologies coerce the submission of the visited. So, science fiction doesn’t necessarily offer a different view of reality – it also participates in that reality. To give another example from the show, we mention in the guide that Neill Blomkamp’s mock-advert for a Soweto robot law-enforcer doesn’t so much posit a worrying future trajectory as it documents a present reality. As Mike Davis notes in his book Planet of Slums, Pentagon MOUT strategists – convinced that future wars will be conducted in the slums against the marginalized, informal populations of megacities – are already planning for the extension into Kinshasa and Lagos of recent high-technology incursions into Sadr City (just one example). By pointing this out, we hope to suggest various entanglements between science fiction and documentary – the present as only apprehensible through SF; SF as a means of securing a global trajectory, and more fundamentally, how most of the artists in this exhibition use science fiction to complicate the usual documentarian or ethnographic representations of Africa.

In other words, the ideas and methodologies of science fiction must be considered critically, and we hope this comes across from the show. In some ways a lot of the works in the exhibition – Neil Beloufa’s Kempinski for example – seek to produce a different form of science fiction from that of dominant cinema. Not only by using African scenarios – reasonably unfamiliar territory for SF cinema before District 9. At some level, the big-budget CGI blockbusters turned out by Hollywood are guilty of extending and gilding global relations of dominion and submission. Not only do their narratives simply allegorize problematic current viewpoints within a (semi-)fictional setting, at an infrastructural level the imaging technologies that are essential to their commercial credibility directly descend from imperial military applications, as some of Harun Farocki’s works consider, for example. It is not enough simply to posit SF as a critique, as it takes on so many forms that support those typical expectations – although we wanted to investigate how it might offer space to resist the usual formulations of global discourse.

Do you see futurism and science fiction in contemporary art from and of Africa as a form of defiance?

Yes, in the sense that the dominant images and narratives about Africa portray a continent “mired in the present” – unable to escape recurring crises born of its unresolved histories. The future tense – which foregrounds desire and possibility – avoids these representations, which are mainly reproduced in the interests of global hegemonies. Equally perhaps, these works defy the dominant forms of SF itself, in their avoidance of the big studio system, in their attempt to produce a future that does not simply extend the present, and arguably in their African settings.

In these ways, I think they seek to disrupt the borders of Rancière’s “regime of the sensible” – producing new visibilities, and subjectivizing those who have been excluded from global discourses except, at best, as victims. Then again, we don’t see Wanrui Kahiu’s film, Pumzi (2009) as necessarily defiant, or at least only in the sense that she is a young African filmmaker producing fantasy SF to rival Hollywood, with all of the attendant geographical and budgetary disadvantages. The film itself reworks many familiar tropes of SF – the post-apocalyptic location, the totalitarian control of limited resources, and the desire to escape a futuristic state and return to a natural state, are all well-explored narratives. Perhaps it is the African setting itself which adds the extra traction to this film.

In a sense, there is a defiance of the science fiction genre too. Historically, SF has been used as a means to create allegories that consolidate difference and fear of the Other or the invader. This was very clear in the allegorical science fiction during the Cold War era for example, which aimed to represent the West’s battle with communism and generate collective fear of the unknown. The science fiction aspects in many of these works reconsider the idea of oppositions and threats.

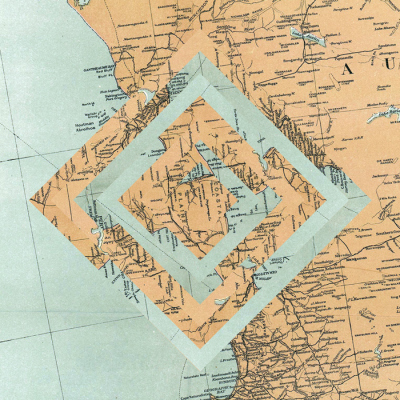

On the ground floor, Luis Dourado’s map [above] and later, Omer Fast’s video installation have been arranged into a kind of labyrinthine maze. It felt to be a very physical way of inaugurating the viewer into the complexities of science fiction and its ideas. Do you agree?

Not really in the sense of the physical experience – this is more or less how Fast’s installation is always intended to be presented. But in conceptual terms, the cut-up map was certainly intended to produce an immediate re-orientation of certain given blueprints – aiming to chart a different reality. We saw its diamond formation more like a portal, or stargate, and for us, this suggested a shift from space into time. This reflects a sense running through our research that, with global space already mapped and conquered (of course, a map is a device of conquest), it is the temporal axis that has become a contested site, as hegemonic forces seek to secure the future for more of the same, whilst others claim it as the possibility of alternative realities. In terms of the art world, the map plots a shift away from the regional representation towards a more complex, refracted viewpoint on Africa. The exhibition is not about African artists. Rather, it seeks to critically approach questions about (regional) representation by bringing together the subject of Africa and SF.

In science fiction itself, as a result of the possibility of reachable life-bearing worlds being unlikely, and in the way that the genre itself has exhausted long-ago the imaginative landscape of other worlds, time also becomes the active principle. So, this map is not so much about making a familiar continent extra-terrestrial, with all the old associations of the Other. Instead, it elevates time over space, disturbing the familiar image-regimes. In another way, and thinking about Omer Fast’s installation, the idea of the cinematic apparatus comes into it. We hadn’t really thought about it as a labyrinth, wondering if it perhaps resembled the sequential waiting-rooms of an immigration office, with flat-screens giving out information (of course, this could have a labyrinthine aspect!) It also, like the MDF viewing structure for Beloufa’s work, seems to disrupt the expected architectural space of cinema, just as it wants to complicate the expected cinematic narratives.

Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction runs at the Arnolfini, Bristol (@arnolfiniarts) until Sunday 1st July.

June 14, 2012

Spring revolution or a summer of discontent?

I’m still mulling over the Openforum 2012 conference, which took place a few weeks ago in Cape Town. The meeting’s theme was ‘Money, Power and Sex: the paradox of unequal growth’. The meeting brought together an interesting collection of artists, activists, academics and technocrats for a pretty open-ended conversation. One of the panels was titled ‘The Arab Uprisings: Spring revolution or a summer of discontent?’ Panelists were Nobel Laureate Dr Shirin Ebadi, Professor Asef Bayat of the University of Illinois, Egyptian writer Mona Eltahawy, and Dr Khaled Hroub of the Cambridge Arab Media Project.

Bayat has talked and written a lot about the ‘Arab street’ as a space of deliberate political action, a space of everyday life, and a space of artistic intervention. The ‘street’ was the theatre where revolutions were enacted in the Middle East and North Africa, but the panelists were asked how they viewed the role of the ‘Arab street’ in the post-revolution period.

Bayat’s response was that while Tahrir square played a crucial role in the revolution, it is a mistake to still bank on the street after the dictator has stepped down. A different venue is needed for the post-revolution struggle.

“The street is the immediate representation of public opinion,” said Hroub. “This is then materialized in political institutions – elections, the democratic process. The post-Arab spring societies are in the process. There are many difficulties but the transformation of the Arab street from a chaotic state of affairs into institutionalized public opinion structures is taking place.”

Hroub also addressed the argument that Arabs do not want democracy. “Arab exceptionalism, the idea that specific cultural and religious structures that do not go hand in hand with democracy, this argument has now been completely dismantled. They have the same longing for freedom and emancipation as everyone else.”

I should note there that during discussions on this issue, the concept of ‘Arab Spring’ was contested – with participants pointing out that societies are diverse – ‘not everyone is an Arab’ – and many asserting an African identity.

Writer and blogger Mona Eltahawy emphasized that in any narrative it is important to remember who told the story. “The Arab street – which street was it? There was this ludicrous narrative – ‘the Nile is a slow-running river, therefore Egyptians are laid back people who like their pharaoh.’ Who likes the pharaoh? American presidents, European leaders. We never told our own story.”

“The presidential elections in 2005 were the first time we had people competing against Mubarak,” said Eltahawy. “But then the street was totally ignored, as it didn’t fit into the narrative, which was invented by old white men in think tanks in DC. On the real street we’re running so far ahead of them that we’re now saying – when you’re ready to catch up, we’ll talk to you.”

Eltahawy and Ebadi talked a lot about the role of women in the revolutions, and the fact that although women played a key role in the uprisings, they are again being sidelined in the post-revolution arrangements. “The time has arrived for women to come up with their own interpretation of Islam,” said Ebadi. “I’m sure that any interpretation given by educated Muslim women will be very different to what we have at present.”

Eltahawy told of having both her arms broken during the uprising, of being detained for 12 hours and being sexually assaulted during this time. She feels she now faces another assault on the Egyptian streets from a patriarchal Egyptian society. “We started the political revolution. We now need to remove the Mubarak in our head and in our bedroom. Unless we do that, the social, sexual and cultural revolution, the political revolution, will not be completed. The revolution was started by a man in Tunisia, but will be completed by a woman.”

Asked about the role of social media, Hroub said “the youth were far ahead of everyone else, including in their use of technology. There was a huge gap that the youth exploited heavily.” But he emphasized that now the security apparatus in every country is fast catching up, with the huge assistance from Western companies. “There’s huge investment in surveillance and control of the internet,” he warned.

Hroub talked of the media as one of three interrelated powers that worked from bottom-up. “Media power, youth power and the Islamists’ power – could not be contained by regimes from the top.” In his conceptualization, social media is the ‘zoom’ in media, while mainstream media provides the wide angle view. He feels they are most powerful when married together – mobile phones and cameras feeding into the broadcast media.

Hroub also warned against too much focus on media as a cause of change rather than a tool, and emphasized that revolutions only happen if the social and political root causes exist. “This is not a Facebook revolution. Media is just a facilitator. In 1978 people used audio cassettes.”

Film Review. Dear Mandela

Midway through ‘Dear Mandela’, Mazwi Nzimande, one of its young protagonists, is rallying a crowd. He’s young, nervous. He looks down at his hands as he takes the microphone, wearing his organisation’s trademark red t-shirt.

“We are fighting for what is ours!” he declares, his energy tangible to the gathering. “Down with people who disrespect our leaders! Down with people who discriminate against shack dwellers!” he cries. “Down with the IFP party, down!” People are answering his calls with enthusiasm, united by his determination. He’s part of a group who have been tirelessly fighting for the rights of shack dwellers in the informal settlement of Kennedy Road, in the outskirts of Durban. Encouraged and at ease, Mazwi shouts on;

“Down with the ANC party, down!”

But with this chant, an excruciating silence halts the crowd.

This scene seems to encapsulate all that ‘Dear Mandela’ — this startling new documentary from Dara Kell and Christopher Nizza — is concerned with. As viewers, readers and writers we are well-used to narratives reminding us of the struggles undergone by activists and the ANC under the Apartheid regime. It is a heavy history to bare, and impossible to ignore. But ‘Dear Mandela’ questions, without ever explicitly asking the question, of whether the ANC’s history now obscures its corruption and immoralities. For Mazwi, part of a new generation of politically aware young people, the ANC is not the untouchable political zenith, not just the liberators of South Africa, no, now they are a government failing him. For Mazwi, life is frustrating, he and many like him feel let down. The film therefore takes the new government of 1994 as its point of departure and instead asks: what were the promises made to a new generation of South Africans when the new ANC took over? Have they been delivered?

In the case of Abahlali baseMjondolo, the group of activists fighting for their rights to stay in temporary settlements without the fear of eviction and violence, the promises have been continually broken or ignored. They fight against the newly written ‘KwaZulu-Natal Elimination and Prevention of the Re-Emergence of Slums Act’ and in particular against Section 16 that allows for the immediate eviction and destruction of shacks or ‘impermanent housing’. They file a suit against the government and demand section 16 be removed for it is ‘unconstitutional’. “They think we don’t know the law. They don’t think we know the constitution. You can’t evict people like us, we know.” I won’t tell you what the outcome is, you’ll have to watch it to see.

But this isn’t just another good documentary about activism. It takes these questions — of political legacies, of the pressures of the historical burdens on younger generations — and examines them. It isn’t just another film about inequality in South Africa, although it does this extremely well — particularly in one scene where members of the group, exiled from Kennedy Road due to threats of violence against them, are kept in a ‘safe house’ somewhere closer to Durban’s port, and realize ‘the grass really is greener of the other side’.

‘Dear Mandela’ dares to document the rising bitterness against the ANC, and its figurehead — Nelson Mandela — by a generation of young people who feel let down by their government. These are people like Mazwi, who are determined to “write a new Long Walk To Freedom, one that takes into account the lives that have been lived in the shacks” and the broken promises of the ANC.

In many ways, the film follows a classic documentary format; smart politicians are shown defending their policies and weaving sugared, neutered statistics to camera, while the tired and determined activists show how hollow those statements really are. Scenes of violence in ‘the shacks’ by anonymous thugs threatening to kill members of Abahlali and their houses destroyed are ignored by police, and politicians fake surprise at the statistics. “We have not been informed of this,” they say.

It’s a usual juxtaposition in political documentaries, yet here it is all the more sharp for the ANC’s self-imagined demi-god-like status in South African politics, and at its head the chiefly untouchable “Jesus Christ figure, Mr. Nelson Mandela”. Can you criticize Mandela? The silence in Mazwi’s speech shows that people are uneasy doing so, and find it difficult to separate Mandela from the ANC. Is it too soon? ‘Dear Mandela’ is asking.

Interspersed with these moments of bold and honest film making are truly beautiful sequences that add another layer to the story, as if the filmmakers had shifted a filter, and a different world is exposed. Kaleidoscopic sequences a little slowed down reveal the intimate and slow gestures of the everyday in Kennedy Road, and uncover another rhythm to the informal settlements. The colors jump, the movements are graceful and moving in the delicacy of their capture. These moments affirm the importance that the people in the difficult conditions of Kennedy Road are a part of something, and are willing to fight together.

In a beautiful end sequence, another young protagonist of the film says “You don’t need to be old to be wise. That is why we need to show our character while we are still young.” True indeed, and ‘Dear Mandela’ is a beautiful and insightful portrait of how young people are trying to define a new politics that does not follow in the long shadow cast by an increasingly problematic ANC leadership.

* Dear Mandela is directed by Dara Kell and Christopher Nizza. It won Best South African Documentary at the Durban International Film Festival, and Best Documentary at the Brooklyn Film Festival.

The United States of Africa

The rapper Awadi was a founder of a Senegalese’s brand of political hip hop. As ‘kola wrote on this blog, Awadi was at the forefront of a 1990s social movement that helped to galvanize a youthful constituency to help elect Abdoulaye Wade as the new president in 2000. “Of course, after [Wade] got the presidency, he disregarded the scores of youths and rap artists that supported him and pandered instead to wealthy and influential members of the business community, which included prominent Mourid (religious brotherhood) leaders.” Awadi continued his activism, calling out Wade over corruption, subsidizing North Korea, electricity shortages and the tragic cases of young Senegalese drowning on small boats to Europe trying to flee unemployment back home. Wade was eventually voted out earlier this year. (The new president is Macky Sall, a former Wade prime minister.) Awadi remains prominent in local politics, but has been casting his net wider for a more continental remit. His last album, Présidents d’Afrique, is an expression of his continental and diasporic politics. Which is where director Yannick Létourneau’s film “United States of Africa” comes in. The film follows Awadi through Senegal, Burkina Faso, South Africa, France and the United States (including the inauguration of Barack Obama) as he records the album with musicians (Smockey, M1 of Dead Prez, Zulu Boy, among others) who share aspects of his political vision. After watching the documentary I asked the Canadian filmmaker about its genesis, politics and why so many political pop stars come from West Africa. But first the trailer.

Can you say something about the process of making the film and your and Didier Awadi’s respective visions? What you were trying to communicate?

My initial idea was to make a documentary on African hip hop. It was an idea that I carried since the end of the 1990s. The idea manifested itself more clearly when I was invited to screen my previous film, ‘Chroniques Urbaines’, in Burkina Faso in 2004. At the time that I was there, they also had the Waga Hip Hop Festival, an urban music festival with artists from Africa and Europe. That’s where I saw Awadi live in concert as a solo artist. He was there with a full band, 10+ people musicians and dancers on stage, which left a strong impression on me — in terms of the quality of the show, Awadi’s lyrics and the relevancy of everything he had to say. I went to see him after the show and told him about my project. I first heard about Awadi back when he was part of Positive Black Soul. Their first album — which was released early 90s — had equally left a strong impression on me. I had had the opportunity to see them live at several big festivals here in Montreal. So I was quite happy to meet him in person ten years later. And Awadi was open to a collaboration. That same time, I met [the Burkinabé rapper] Smockey who also features in the documentary (more about him later). That’s the early genesis of the project.

I quickly realized I could not just do a film on “African hip hop”. That was too broad and I wasn’t interested in doing a who’s who of African hip hop. That would rather be something for a book. I could not just make a film about ‘music’; because what these artists are doing is ‘bigger than hip hop’. They are concerned with social justice, not only in their own countries but on the African continent as a whole. I needed to go deeper to understand better their commitment to political hip hop. The film took about four years of research, development and financing. It was very difficult to find anybody interested in Africa and/or anybody interested in (African) hip hop. It took a long time but I finally managed to pre-sell it to four Canadian broadcasters, and then a fifth broadcaster (the South African public broadcaster SABC1). After that, it took me about two years to shoot (ninety days) and about a year of post-production. So overall it was a 7-year process. That’s the short version.

My interest in Africa goes deeper than just my interest in hip hop. My first encounter with the continent was when I travelled to Burkina Faso in 1993 to visit my mother who was working there for an NGO. She lived there for 9 years. I wasn’t particularly interested in Africa. I had all these stereotypes in my head as a young Canadian citizen. I didn’t know much about what I was going to see or what was going to happen once there. But that first trip changed me and my perceptions: the people that I met, the stories that I learned, my hearing about the story of Thomas Sankara who had been killed five years earlier. From the youth of Burkina Faso who saw him as a fallen hero and by studying Sankara, I found out about the unhealthy relationship with France and their former African colonies; I learned about the issue of debt and its use by the IMF and the World Bank to justify privatization of health, education and other common goods. I got more interested in the socio-political aspect of what was going on in Burkina Faso but also throughout the continent, as the same dynamics are at play in other African countries. This film for me is the result of 20 years of traveling back and forth, lots of reading, meeting people, engaging in conversations and finding out more about a history I didn’t know of. I realized I didn’t know any of the African heroes and thinkers like Diop, Nkrumah, Lumumba, Nyerere, Biko, Cabral or Hani. It’s only with time that I got better acquainted with the concept of the United States of Africa, a concept initially put forth by Marcus Garvey (and which was pushed further through Nkrumah etcetera). That concept became the frame of this film.

This film has become for me a way to challenge the stereotypes and the negative representations I had of the African continent and the contribution by Africans to civilization and history — too often portrayed in a negative way as if Africa was somewhere outside of history. Sarkozy’s speech in Dakar in August 2007 (where Sarkozy said Africans had “not fully entered history”) sums up that colonialist point of view very well. This film is my way to talk about this other Africa we unfortunately don’t know much about.

In the film, Awadi focuses his energies on at least three contemporary presidents. The film suggests that two of these fall short: not surprisingly, he has clear dislikes for Abdoulaye Wade and Nicolas Sarkozy. In contrast, he is excited by Barack Obama’s ascent to the American presidency in 2008 and even defends his position against that of critics like M1 of Dead Prez, who’s also a collaborator on Awadi’s album “Présidents d’Afrique” and distrusts Obama (to be fair, Awadi mostly sees symbolic value in Obama’s election). As things stand, Sarkozy and Wade are now both confined to history. Has Awadi’s position on Obama changed? What is your position vis a vis Obama?

I understand Awadi’s position when he says that what is important for him is the fact that the son of an African father is now the president of the United States of America. That meant a lot to him then in terms of symbolism. No matter how dark your skin is, you can be the most powerful man on the planet. But other than that, Awadi clearly says in the film that he’s aware Obama won’t change American policy, he’s just a part of a system that is much bigger than himself. Awadi is far from being naive. M1, in the film, is much more reactive and outspoken about what Obama stands for. But M1 also understood what Awadi was saying and where he as coming from. It was important for Awadi to be in Washington DC for the inauguration. It was an opportunity to witness history. But we now see things haven’t changed that much since — be it on a foreign policy level or on a national level; think: the reinforcement of the Patriot Act, the military spending and the extra-judicial killing outside the US and AFRICOM. All of that just shows it’s more of the same.

As things stand, yes, Sarkozy is gone, replaced by a socialist government, and Wade is gone as well. But what Sarkozy is recorded saying in the film is still relevant. His Dakar speech was a resumé of the colonial mindset which has justified a perpetual involvement by France (and other world powers) in African affairs and politics, always for the control of resources. That’s what it is. The dream of the West is having an Africa without the Africans. They really don’t care about the development of the African people. Again, the IMF and the World Bank’s policies encourage the different countries to remove their trade barriers which are essential to developing a national economy yet these same trade barriers are used effectively by the US and Europe. Why is that? It doesn’t make sense. There needs to be trade barriers in order to stimulate national growth and economy. Some form of protectionism is needed to develop and protect local industries — whether cultural or agricultural, in Africa.

My position regarding Obama? I have no hope in the president of the United States. You can now be arrested and searched in the US if police says you look suspicious. Protesting close to a president can get you in prison. These laws were put in place by Obama. Is that democracy? Let’s not be blind. It really is the business world controlling governments everywhere. It’s the 1% against the 99%.

Awadi is very articulate about what ails Africa (harsh and indifferent global realities along with profligate African leaders). To confront these realities he offers the examples of past anti-colonial and African (and black) nationalists leaders as well as his music. Yet he also concedes that symbolic politics won’t be enough or get us very far, and suggests people “need to organize.” Yet Awadi leaves the latter option open. Is he deliberately leaving that open? Does he have a political program and if so what is it?

Awadi is not a politician. He’s an artist. And artists have limits in terms of what they can do as artists. You can sing about revolution, you can talk about the conditions of the people, you can pinpoint specific problems or offer solutions. You can encourage people to go out into the streets. You can serve as a voice for the voiceless and speak truth to power. But at a certain point it’s up to the people to organize politically. And Awadi knows that. That’s why he says that if we want things to change, we need to jump the fence and commit ourselves beyond just attending concerts and lifting your fists in the air screaming ‘revolution!’.

If you look at history and the revolutions that have happened (e.g. the fall of the Berlin wall or the struggle against apartheid), it’s because people organized en masse. There was mass education and mass action. This is what the film suggests at the end with the example of South Africa and the speech of Blandine Sankara. Smockey for example goes beyond his role as a musician and reaches out to the kids as an organizer of sorts — not with a political party but through the ideal of humanism and social justice. He confronts the kids with their fear. Their fear of action. I believe it’s only through action that change will come. If there is to be change, it needs to come from the people, and that includes the artists who need to step down and go into the streets and organize. There’s no other way. That is what Awadi meant when he says politics of symbolism won’t be enough, nor get us very far. Yes, we leave the question open. Deliberately. We wrote the film and left it open — and went through the whole narration with Awadi too so it could be his as well — because it’s not up to us or to Awadi to say how the people need to organize. People know what to do and can do it very well. Take the recent of example of what happened in Burkina Faso last year, where the same dictator has been around for the last 25 years, with support of Western powers. There were huge protests by youth and young adults who were protesting the beating and killing of a kid in the police station — protests that where barely covered in the mainstream press here. Or in Senegal, where you have hip hop artists who stepped down as artists and started organizing politically through Y’en A Marre. That’s a very concrete and real example of people taking things into their own hands as citizens, not as artists. Getting down with the people, doing education and organization. Whether through a political party or just as citizens fighting for social justice. I don’t think Awadi has a political program other than letting the people speak and let’s have justice prevail. There are politicians out there who do have a political program and those we believe in should be supported. Real people democracy. That’s his program. (Or at least my personal interpretation of what Awadi stands for.)

As discussed earlier, the film was completed before the recent Senegalese elections that saw Wade voted out of power, but we get glimpses of Awadi openly criticizing and ridiculing Wade’s policies. Apart from Awadi’s more continental and symbolic politics, what was his role in the recent political struggles inside Senegal? What is his relationship to groups like Y’en A Marre?

I know he was supportive of what Y’en A Marre were doing. Yet, he decided to align himself with the broader M23 movement — a coalition of which Y’en A Marre was part of, bringing together citizens, political parties, NGOs and other interest groups from civil society. He has worked with artists that are part of Y’en A Marre. He recorded some songs during the events and he was very outspoken about it in national and foreign press. He’s always been very critical of governments that are messing up. He’s not a kid anymore. He’s in his forties, he has a lot under his a belt as a man, as a father, as an artist, as a citizen, and I think he’s got a very acute understanding of the politics in Senegal and in Africa in general — an interesting point of view as to what needs to be done for the country and the continent to emerge as a force. First and foremost in the best interest of the people.

I was very impressed by the Burkinabé rapper Smockey (above). He is very courageous and politically involved. Can you say more about him and his musical and political movement in Burkina Faso. He is not alone with his stance in that country, right?

Smockey is definitely not alone. One of his friends Sams’K Le Jah, a reggae artist who is very outspoken, was attacked by the government and received death threats yet continues to fight for social justice in Burkina Faso. Smockey is an impressive character, an artist, and a very courageous citizen. (When I speak with Awadi we worry for Smockey’s safety because he’s risking his life doing what he’s doing.) At the same time, Smockey knows it and there’s nothing that will stop him. He has received death threats before, directly and through his family and close ones. But, fortunately, he’s not alone. He is part of a larger network and is known in and outside the country. It gives him some sort of protection because the Burkanibé government wants to be seen as being open and democratic. Partly because in 1998, elements of that government killed an investigative journalist, Norbert Zongo, who was critical of the corrupt elite of that country, of the government and the people close to the government — which made him an easy target. When he was killed there was almost a coup d’état: people came out massively, and President Blaise Compaoré almost stepped down. So yes, it’s dangerous in that country. Others in the past have disappeared and were killed in strange circumstances. Smockey, again, is not a politician. And Awadi is concerned about the development of the people and his country. When you see the exploitation and the poverty of the people, you can’t just sing about love, sex and party.

There is an urgency and an everyday threat, there is hunger, there is exploitation and repression. So I understand and can only agree when they say they have a responsibility as artists to talk about what is going on because many people are afraid to talk.

Even if there’s an illiteracy rate of 85% in a country like Burkina Faso, the word gets out thanks to artists like Smockey, and people learn through him and others like him about what’s really going on, and how the elite is only really interested in preserving their privileges. These artists have an influence because they’re using rap and words everybody can understand. Hip hop is the music of my generation. We grew up with that music. That is, I guess, also why I was interested in doing this film.

Why do you think Thomas Sankara holds such attraction for especially young West Africans?

Sankara is an important political figure on the continent. Not just for West Africans but also for anyone who’s interested in politics and history. He was a revolutionary who proved that even the poorest country on the planet could lift itself out of poverty. He set an example for the oppressed people of the world. I believe that’s why people appreciate what Sankara managed to do for Burkina Faso in only four years. Younger generations know that he wasn’t perfect but he was always seeking and fighting for that ideal. He was a pan-africanist as well. He was killed by the actual government with the complicity of several other African countries, and France, to set an example to anyone who would consider taking that route. Sankara tried to break the vicious circle of debt and privatization that enslave people around the world.

Sankara is called the Che Guevara of Africa by some, but many are inspired by Sankara because of what he has achieved in a mere four years. You might be the last country on the development list of the UN, but that’s no reason why you can’t develop yourself. You might be the poorest country in the world, it is within our means to get ourselves out of the underdevelopment and to change things around. He showed that was possible through massive vaccination, eradication of famine, through putting wome in power in all the key sectors of society. He’s an example for every developing country. (Watch: ‘Thomas Sankara: The Upright Man’.)

Finally, I kept thinking of Awadi as a younger version of Tiken Jah Fakoly or Fela. What is it about West Africa that it produces political pop stars?

That’s an interesting parallel. Awadi and Tiken Jah are about the same age and they have collaborated together (on Coup de Gueule’s first track, ‘Quitte le pouvoir’). And yes, Fela is definitely part of the family of thinking. But I’m not sure why so many political pop stars come out of West Africa. Is it because there’s such a strong popular culture which is rooted in consciousness or politics? When you listen to, say, Nigerian or Ghanaian hip hop music, it’s harder to find political conscious artists. Of course there are, but it seems as if you go to Burkina Faso or Senegal, most artists are politically conscious. Probably because there’s so much wrongs in West Africa. Look at Nigeria and its oil politics, or Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso and Senegal: too much corruption. You’ll have people who barely eat once or twice a day. It is tough out there. There’s massive unemployment, youth is disenfranchised, there’s not a lot of opportunities. People are pissed-off because they’ve been promised development, by their government and financial institutions such as the IMF and others. Now, five, ten, twenty years later, we see that nothing has changed. It has become harder than ever. People are fed-up. So the fight of Fela, or Tiken Jah, is only more relevant today. This is something we need to hear. You often learn much more by listening to these artist than to reading news-feeds from AFP or Reuters. If you really want to know what’s going on, wherever you are…listen to these politically conscious artists. You’ll have a better perspective about the people, and a better understanding of the powers at play in those countries.

* ‘United States of Africa’ is available to US cable subscribers through InDemand (VOD and Pay-TV) since May 15th and on iTunes as from July 3rd. The film is currently touring film festivals worldwide. Tom Devriendt transcribed the interview.

June 13, 2012

Wainaina’s writing out of depression

Guest post by Jonathan Duncan

The wobbly giraffes doing the splits next to my bed reveal my recent bedtime narrative. Subconsciously and adrift, I appear to have amassed a week long collection of literary conquests, scampering around on my bookshelf. So, after placing them apologetically back on their communal bed — their shelf — I unpacked the delivery of Binyavanga Wainaina’s book, One Day I Will Write About This Place.

Opening in Kenya in the late 1970s, the birth of the story sees Wainaina at his most playful. A young boy of seven is recollected in acrobatic and staccato sentences. He exchanges tangential poetic imagery — imbued with colour and lucidity — with structurally orientating map pins, which place you within the geography of the narrative. These pins serve as pricks for departure, and for the divergences and plasticity of his imagination and attention as “the shape” of his ideas start to “form. There is air, there is water, there is glass. Wind moving fast gives form to air; water moving fast gives it form. Maybe … maybe glass is water moving at superspeed, like on television, when a superhero moves so fast, faster than blurring, he comes back a thousand times before you see him move.”

These early sections feel like a memory, present but not wholly there, levitating above the pages, rather than just being self-evident of a ‘memoir’. His early self is absorbing — accreting himself and his landscape — by a multi-sensory osmosis. A landscape punctuated by Kenyatta, Afro’s, Diana Ross and the Jackson Five, careering out of TV’s, radio and posters.

If I focus, I can let it into me, let in the whole wide woosh of the world. I grit my teeth, harden my stomach […] If I get that moment right, I can let my mind burst out of me and fold into the world’. He exhibits a helpless fascination with sound; the sound of words, dividing the world into ‘sounds of onethings and the sound of manythings’; sketching people, history and emotions with the sounds they make; ‘frying sausages sound like rain on a tin roof, which sounds like a crowd.

Going even further to construct a “new word, my secret”, ‘Kimay’, a “talking jazz trumpet: sneering skewing sounds, squeaks and strains, heavy sweat, and giant puffed-up cheeks, hot and sweating; bursting to say something, and then not saying anything at all; the hemming and hawing clarinet. Kimay is yodelling Gikuyu women.” For Wainaina, ‘kimay’, is a way of seeing, of hearing.

Such a persistent use of sound livens his images, making them heard, orchestral. But, within the colourful compositions of sound there is a counter-melody, a disquiet, that radiates from his relationship with the exterior world of people and things and that which is interior. Recollections are assembled on tensions and imbalances. Where they interweave, a place forms for Wainaina, which he fears, “afraid of being hijacked by patterns”. Visual and emotional encounters introduced in the infancy of the book, like undercurrents, emerge in shifting and recomposed forms throughout, some painfully acute while others more quietly so.

Already by the age of 11, Wainaina is retreating to a refuge in fiction. His Ugandan mother interrupts his reading and stops him going to the library “because they found out that I had managed to spend the whole year avoiding math homework and reading novels in class”. A seeming place of safety to evade the impositions of his school and parents which, is for “future doctors, lawyers, engineers, and scientists” — a prescription that makes Wainaina uncomfortable and itchy, like wearing someone else’s clothes. During his time at boarding schools the sentences become less flighty, instead becoming increasingly affecting. Still ravenously reading but now turning the pages with a thumb “mushy and bleeding, with pus. Over the last few months, I have been peeling my nails with a razor blade during night prep. Short, right bursts of quiet peeling, nibbling and scraping, only stopping to turn the page of my novel.”

Writing on depression in Africa is a rarity. Here, Wainaina’s book seems singular. While at a South African university studying commerce, Wainaina’s equilibrium alters dramatically. His unevenness sees his tight rope walker plunge, as he “moves out of the campus dorms and into a one-room outhouse [falling] away from everything and everybody”. Within this room he barely leaves, the scope of the writer-camera adjusts to macro. The scenes thickly stick to objects surrounding him, bound in vignettes:

when you are lazy and locked in your room for days, fluff, in the right light, looks like thousands of starlike creatures somersaulting in the air. They swell out of nothing and somersault and burst or vanish again into nothingness, and others swell, as if something on the other side of reality is blowing the smallest bubbles in the through holes we can’t see.

Only reading remains; exchanging books and stealing a few from a second-hand bookstore. Wriggling “back into my own pillow [...] tears start falling, and they don’t stop.” On the disparate occasions that the gravity of the room frees Wainaina to leave, it is only a bottle smashed over his head — the resolution of a fight — that pierces his stupor. He describes it lovingly as “wonderful. There are little delicious explosions in my head for days.” Such a long period of paralysis, a disfiguring depression, is contained in a seemingly short section. As if resurrecting this time is too painful, or the time was stolen away from him. But its re-emergence is discernible thereafter, returning in a less debilitating form, as Wainaina awaits ‘the next surge’.

By the midpoint of the book Wainaina still appears nomadic, having lived in different geographical and mental locations without explicitly announcing a mentionable love for one above, or besides another. Yet, weary of his mental health he returns to Kenya, “I want to be home,” he writes, “just to be home.” His continuing struggle and recovery is then perceived and expounded through his family and their concern. “They are worried about me and, for the first time in my life, worries enough to not bring it up.” His father endeavours to talk, help and nurture allows Wainaina to unveil the greatest insight into their relationship, which has been written about quietly until now. His father’s attempts are noticed, but avoided by Wainaina whose “face was, as usual, hidden behind a novel,” like a shield, as he was still riddled with guilt about the unfinished efforts to complete his degree. Wainaina closes the chapter with an admission; “what a wonderful thing. I think, if it were possible to spend my life inhabiting the shapes and sounds and patterns of other people.” He makes an agreement with his father to go back to university and finish his studies. He lasts just a month.

At the end of a family visit to his mother’s home country of Uganda, enveloped in the warmth of his multilingual, multinational family, love does bubble in his words and allows the reader entry into his idea that the “world of his family is as solid as fiction.”

He decides, “one day I will write about this place.”

His ascension as a writer occurs in grades and shades, with expanding successes, without the burdening weight of indecision, guilt or his families impositions. Accepting his trade and denying the gravity that once consumed him, “no, no, says my self-pity, I am not a spineless flibbertigibbet.”

Home in Kenya, following his mother’s death, he found he could not leave. Sentences increase in size, heavily punctuated while expelling a commentary of the upcoming Kenyan elections and the country-wide tension formed by uncertainty. At times, it seethes, reminding you that really you are reading a memoir.

But yet again, Wainaina retreats, after tearing up his ‘voter’s card’, he boards a plane to Lamu, “as far away from the poisonous election as I can get and still be in Kenya.” This sense and actuality of distance, so integral to Wainaina, permeates the book and dictates his writing, living with people in his head, instead of close beside him. It is the becoming of an artist not by great discovery or conscious choice but by an innate natural necessity; a process for Wainaina, to remain buoyant. Providing rudder and keel, to avoid “falling into and getting tangled by messy shapes,” instead giving ‘patterns’, shapes and sounds form. Pushing into places of his experience that had no previous articulated understanding, a resolution of the images that plague him and a validation of language’s ability to place and orient in time. “When I wake up to an awareness of place and time, I find I have gone far away from others, and I do not have the confidence to make my way back. In a way, writing keeps me close to people.”

The predominant motif is introduced within the initial chapters and pervades throughout, where the line of the story turns and closes a circle. Elegantly painting a concluding symmetry between what is made to be heard, ‘kimay’, and Kenya, its people and writing. “It is a literary form, and the song, the tune of the song, does not follow a separate and parallel musical scale: it too is a slave to the story, its peaks and troughs, its moments of wisdom, its bad behaviour. And people dance, moving around the music to inhabit the story.”

The connections in the book and the passages of time are clear and meaningful; but without attention could disrupt, like little rocks in the road. Which could be accounted for as the book developed from shorter published works. The alliance in structure nurtures a wholeness, but not into a such coherence to define it definitively as a memoir.

* Jonathan Duncan (@Tobe_averb) is a writer and designer living in London. Kwani? recently launched the East Africa edition of One Day I Will Write About This Place.

The New York Times goes to Zimbabwe*

Lydia Polgreen’s recent NYT article “In Land’s Bounty, a Political Chip,” while a good introduction to one side of the indigenisation policies of ZANU-PF, is far too nice to the lead character, Savior Kasukuwere and lacks a serious analysis of the political situation in Zimbabwe today. The report linked to in the story by Derek Matyszak of the Research and Advocacy Unit in Harare does a better job demonstrating just how tenuous the indigenisation plan is that Kasukuwere has worked out with South African companies, particularly South African-owned platinum mining Zimplats. Polgreen correctly points out that companies such as Old Mutual and the large mining companies are now paying out directly to local communities as part of the cost to do business, as they do in South Africa, but the turning over of ownership to Zimbabwe’s new rich, as represented by Kasukuwere and others in ZANU-PF is less clear.

Polgreen necessarily has to be careful working and traveling in Zimbabwe, and therefore doesn’t want to antagonize a powerful figure in the ruling party such as Kasukuwere, but all the same there is more to Savior than handing out checks to ululating and grateful constituents. For example, a recent story by Zimbabwean reporter, Tererai Karimakwenda, claims that Kasukuwere has urged unemployed youth in Zimbabwe’s second largest city Bulawayo to take over Indian-owned businesses in that city comparing Kasukuwere to Idi Amin’s disastrous indigenisation policies in the 1970s.

Some have compared Kasukuwere to South Africa’s Julius Malema, as a younger leader who uses his own personal wealth to show poor youth that they too can make it. Like the growing number of prophet preachers in Harare, Kasukuwere links power and money and the promise of land accumulation to those with exclusive membership in ZANU-PF.

Roy Bennett, the Movement for Democratic Change leader, who was never sworn in as deputy Minister of Agriculture because Mugabe and others wouldn’t have it, gave a speech in Oxford two weeks ago where he referred to Savior Kasukuwere and what he represents:

Indigenisation has flipped the order of priorities. The propaganda is still populist in its presentation, but Zanu-PF knows that no-one is listening.

And if you look closely at the slide show that accompanies the NYT’s story, the expressions on the faces of the Binga crowd show this. Bennett goes on:

There is no chance of pulling back electoral support. The talk now hides, very barely, sheer gluttony and rampant avarice. This is a disease, an addiction unhinged and uncontrollable. Many of Mugabe’s acolytes have become unimaginably rich. But, now, in Zimbabwe, enough is never enough. The perpetrators, the white and black mafia, Zimbabwe’s Cosa Nostra, connive, steal, smuggle and murder together, shifting the country’s resources out the back door and trampling the people underfoot.

Bennett went on to say there is no racial distinction in Zimbabwe, whites and Asians (Chinese) are able to join in the accumulation if they play by ZANU-PF’s rules. He attacks companies such as Old Mutual for entering into a partnership with the ZANU-PF cronies:

Bottom feeders from South Africa, many of them outwardly respectable companies like Old Mutual, have trampled on ethics and human beings in the stampede for the Zimbabwean carcass. Arrogant and hard-hearted, they have shown no hesitation in standing on the heads of the Zimbabwean poor as they cavort with the Zimbabwean rich. They believe they are untouchable, practicing, as they see it, their own cunning brand of worldly-wise expediency-and now practicing it, judiciously they think, at home in South Africa. ‘TIA’, they say-‘This is Africa’; ‘walk in with the bowler’. What they do not realise is that they are bringing with them the people and practices that will annihilate the very foundations upon which their comfortable lives are based. South Africa is ripe for the Zanu-PF variety of national liberation. Ethnic and racist propaganda will work a treat for those whose mouths have been fed by the same corrupt corporates and whose appetites have been whetted yet further by the feeding frenzy across the border. Already there is a dialogue between the demagogues in Zimbabwe and South Africa.

The president of the ANC Youth League, Julius Malema, visited Zimbabwe to learn some of the tricks of the trade from our Minister for Indigenisation, the ironically-named Savior Kasukuwere. Malema probably thought he had to give them something back, so he taught them the song, ‘Kill the boer’, which was banned in South Africa-though they changed the lyrics to ‘Kill Roy Bennett’.

It is good that Polgreen introduced a wider audience to Kasukuwere and ZANU-PF’s attempts to force South African companies to create photo-ops with large checks in poor places like Binga. But readers should know that this does not mean ZANU-PF is now suddenly looking out for the interests of the people. Zimbabwe would never had gotten into the situation it did had that been the case. ZANU-PF remains committed to defending its own control of the state, mineral wealth, and the deals with international ‘bottom feeders’ at all costs. That is why ZANU-PF clamors for another election as they mobilize youth militias willing to give that up in a national election. That is why the succession battle in ZANU-PF is so fraught with danger at the moment—and apparently Vice President Joyce Mujuru, one of the most powerful ZANU-PF leaders next to President Robert Mugabe, criticized Kasukuwere for not doing enough for her and others in her faction in recent party elections. That is also why ZANU-PF elites refuse to give up control of the diamond mines that could, if handled in properly, help get Zimbabwe’s economy back on track. Instead, ZANU-PF insiders remain in control of the revenues along with their Chinese and Russian partners.

These links between ZANU-PF insiders, the military, and a global shadow economy would be a good story for Polgreen to take on next, along with the continued killings of MDC activists, such as the one that recently occurred in Mudzi. A ruling party that has managed to kill and torture the opposition with impunity for as many years as ZANU-PF is not about to change its ways without a much more serious challenge. Polgreen may want to look to see if the UK and the US can play a more active role in challenging this entrenched strategy. Binga and photos of colorful fabrics in nice light are par for the course for the NYT’s portrayal of Africa these days, why not try something old school like really covering politics and economics?

Polgreen does a great job in her article explaining why Zimbabwe is potentially so wealthy given the mineral wealth found there. It should be hoped that the NYT and the American media more generally could focus on the real political struggles in Zimbabwe and not think that the government of national unity has brought Zimbabwe out of a period of violent political conflict.

* I didn’t write the post, just posting it. This post was sent in by a reader who wishes to remain anonymous.

June 12, 2012

Steve Bloom photographs 1970s Cape Town

The London Festival of Photography has opened, and one of its most appealing features is an exhibition of images by Steve Bloom – Beneath the Surface – a unique document of South African life in the 1970s. There are images of squatters camps, protests (and police violence) in Cape Town, the demolition of buildings in mixed-race neighbourhoods (later repurposed as ‘white areas’), as well as intimate portraits of people in their homes and close-ups of wrinkled and emotionless faces.

One image, above, simply called ‘Manenberg, 1977’, shows a bare-chested man standing in a room whose bare-brick walls we can only dimly see. His face is half-turned towards a light source out of shot – a window, presumably – which softly illuminates his head and torso. In his arms a baby whose tipping head, open mouth and hand outstretched towards the viewer provide dramatic lines which off-set the man’s firm grip and solid stance. The baby’s stomach, a shocking white bulge against the shadowed man’s torso, feels like the focal point of the composition. The circumstances of the photograph are unclear: it doesn’t feel like other pieces of photojournalism, doesn’t yield up a particle of pre-conceived meaning for the viewer’s consumption.

Next to this, the theme is reprised in another photograph, also ‘Manenberg, 1976’, in which a wild-haired young child looks warily up at the camera. She is clutching a white plastic doll wrapped in light swaddling, pressing to its cheek against her mouth, its eyes unfocused and slightly insane, its arms stretched out with a pre-fabricated hunger for affection.

These images – from a series taken in the township outside of Cape Town in 1976 (about which, incidentally, Abdullah Ibrahim’s classic piece had been written two years earlier) – are images of empathy and tenderness, found in closely observed moments of relation between light and dark bodies.

This relation appears to be the organising theme of Bloom’s work of this period. In an essay, published by the Guardian and distributed as a small freepaper at the gallery, the photographer reflects that “In the years that I lived in South Africa, I felt discomforted by the unearned rights assured by my white skin.” The work documents different times and places of South African life, the domestic and public existences of polarised demographics: a man sunbathing on Sea Point Beach, someone soliciting donations to a charity for ‘spastics’, women walking past segregated toilets.

One of the unearned rights Bloom’s race permitted him was access both into the policed zones of white society and into exclusively ‘coloured’ townships, and the photographer used this to observe privilege and its opposites, juxtaposing images of the leisure of an affluent society and the suffering of an oppressed people. One series of images shows two children walking on a pavement consuming ice creams while, in the background, one man tends to a woman who appears to be injured. The caption reads: “Green Point, Cape Town, 1977; a residential suburb close to the city centre. The effect of apartheid was to engender feelings of indifference across the colour line.” The distance (and awful intimacy) between bodily suffering and pleasure in the same public place to which these images attest is coupled by an unerring tenderness. This is the gaze of the photographer, both removed from the situation and – almost embarrassingly – concerned by it.

Bloom left South Africa in 1977, landing in London the day before Steve Biko’s funeral, and lent to the International Defence and Aid fund for Southern Africa, who used them to publicise and raise funds for the anti-apartheid movement. This prevented the photographer’s return to the country of his birth for thirteen years.

The exhibition, at the Guardian Gallery, continues until June 28. Some more of these images can be seen here.

June 11, 2012

Struggles over memory in South Africa

[image error]

Struggles over memory are commonplace in contemporary South Africa. The 1980s are an especially contested part of its past. That decade witnessed a mass resurgence of popular struggles that picked up a thread of civil opposition going back to the 1976 Soweto uprising. From outside South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC) stepped up its armed struggle and sanctions campaigns; inside the country the United Democratic Front (UDF)—a loose federation of women’s, youth, and civic organizations founded in 1983 in Cape Town as a response to tepid government reforms—coordinated rent, service and consumer boycotts; and a new national trade union federation privileged political struggle. The state responded with more “reforms,” states of emergency, proxy wars, assassinations, and mass detentions. Today legal apartheid is a distant memory for most South Africans. The reasons are multiple: a youthful society because of poverty and, more recently, an AIDS pandemic; preoccupations with consumption and class mobility; and a rush to forget on the part of most whites. For the most part the ANC’s current behavior—associated with corruption, cronyism and personalism—is presented as an extension of how the ANC and other opposition groups operated throughout the 1980s.

This revisionism is contested, however, by ANC and other struggle figures. The poet-politician Jeremy Cronin has decried such “revisionism” (Cronin 2003). He denies that the history of the ANC’s armed wing can be reduced to what happened at “Quatro detention camp” where ANC generals executed dissident members, or that the legacy of township self-defense units that defended communities against a “bitter apartheid-launched low intensity conflict strategy” can be downgraded to a story of “indiscipline.” Apartheid-era struggles over education, similarly cannot reduced to a call for “No education before liberation,” a slogan that “was roundly condemned by both the ANC and the UDF at the time.”

Cronin may be right that such revisionism pervades popular culture. Fortunately, however, the data about the “real thing” is out there. Documentation of struggle history (and of the extent of oppression and its legacies) is increasingly available in and outside South Africa, particularly online. Think, for example, of Padriag O’Malley’s biography of Mandela’s Robben Island colleague Mac Maharaj (the book comes with an online database of interviews and commentaries); or the website sahistory.org.za with its short essays, biographical sketches, scanned books, and copious references maintained by photographer Omar Badsha in Cape Town. Similarly, I can recommend Overcoming Apartheid, an online compendium of video interviews, rare photographs, and historical documents. (There, for example, I saw a former colleague, Shepi Mati, recall his activist roots in the Eastern Cape.)

The progenitor of all these is the ‘From Protest to Challenge’ series, the invaluable multi-volume collection of documents from South Africa’s liberation struggle, of which the sixth and final volume recently appeared. It’s worth recalling the history of the series.

Tom Karis, an American diplomat, had been an observer at the treason trial of 156 opposition leaders from 1956 to 1961 and had befriended one of the defense lawyers, George Bizos. A few years after the trial ended, Bizos gave Karis, now an academic, a set of the thousands of documents collected by the state to use as evidence in the trial. Karis, now working with another academic, historian Gwendolen Carter, also obtained a set of the trial transcript. In 1965 the Hoover Institute decided to publish some of the trial, to be selected and introduced with historical essays by Karis and Carter.

Originally Karis and Carter had planned to publish a single volume with an introductory text and a biographical appendix. This proved insufficient and eventually they produced four volumes spanning the period 1882-1964. Volume one covered the period 1882 to 1934, volume two 1935 to 1952, and volume three (which was banned in South Africa) 1953 to the 1964 Rivonia trial. Volume four was a series of short biographical sketches of resistance personalities.

Karis wrote the texts of volumes two, and together with Gail Gerhart, the texts of volumes three and four; Sheridan Johns III authored the text of volume one. Carter provided editorial oversight. All are or were American political scientists. These books, published in the 1970s, are now out of print, but revised editions are currently in preparation by Gerhart.

After a long hiatus during which the South African government denied them visas for many years, Karis and Gerhart resumed the series in 1997 with a fifth volume that examined the period 1964-1979. Volume six, edited by Gerhart and Clive Glaser, a historian at the University of the Witswatersrand in Johannesburg—and the first South African to be a co-author in the series—focuses on the 1980s.

Like the previous volumes, number six consists of introductory text plus primary documents. The text chapters are broken up thematically and historically, with sections on “reform and repression in the era of P. W. Botha,” the securocrat president whose regime and response to the lingering political and economic crises came to define the decade; the wide spectrum of internal protest politics; exile and underground politics; and finally, the secret early phase of political negotiations.

Part Two, the bulk of the book, consists of primary documents organized to parallel the essays in Part One. The book ends with a bibliography and a detailed index.

As with previous volumes of this series, the essays in Part One are well researched, clearly written and concise, providing useful context for the selected mix of organizational minutes, reports, letters, statements, pamphlets, interviews with struggle leaders, and other documents that follow. Part Two opens with Percy Qoboza’s March 1980 speech at Wits University calling for the release of Nelson Mandela and closes with Mandela’s speech from the balcony of the Cape Town City Hall to a crowd of thousands on February 11, 1990, the day he was released after serving twenty-seven years in prison.

The 180 documents in between offer stark evidence of police brutality, executions, forced removals, and multiple states of emergency. But we also get a sense of how resistance movements sought to define their own struggles. The documents also reveal the ideological and strategic contests that presaged the revisionist debates of today.

Protest politics in the 1980s were dominated by piecemeal government reforms that included new local government structures for Africans and separate and unequal parliamentary legislatures for coloureds and Indians at the national level alongside the whites-only legislature. The latter institution, of course, held real power. Documents of religious, sports, labor, and community organizations show that instead of dividing resistance, these reforms served to galvanize and unite opposition to the state. Though localized concerns drove the UDF, these struggles were always linked to an overarching opposition to apartheid, and in some senses, to the negative effects of an exploitive capitalist production system.

We also see evidence of the ANC’s work to win the propaganda war in Europe and the United States. For example, Gerhart and Glaser include a transcript of a meeting at Britain’s House of Commons in October 1985 at which Oliver Tambo and Thabo Mbeki respond to hostile questions from British MPs. In one exchange MP Ivan Lawrence lists a number of instances of ANC bombings in public places and assassinations of security policemen, community councilors, and former ANC members turned state witnesses. He wanted Tambo and the ANC to condemn any future terrorist acts. Tambo responds:

Let me get back a little to the first part of the question … In 1981 one of our most outstanding leaders [Joe Gqabi] was assassinated by South African agents … In that year South Africa had raided our people—raided Mozambique—and massacred very brutally some 13 of our people who were simply living in houses in Mozambique. That was 1981. In 1982 the South African army invaded Lesotho and massacred not 19 but 42 people, shot at point blank range. 42. Twelve of them nationals from Lesotho. So there was this mounting offensive against the ANC. I think your question fails to [relate to] this aspect: that we were victims of assassinations, of massacres, and in return for what? We were not killing anybody … An armed struggle is an armed struggle. People die. It has been fortunate perhaps, in that time that there have not been so many people dying on the other side of the conflict … [On our side people] have been hanged, they have been sentenced to long terms of imprisonment, for exploding a bomb, [a] bomb that destroyed a pylon; sentenced to life imprisonment. That is violence. This is what we are going through. As to these other people you are mentioning, we cannot condemn it. That is part of the struggle. The enemy is the enemy. (p. 584)