Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 518

October 15, 2012

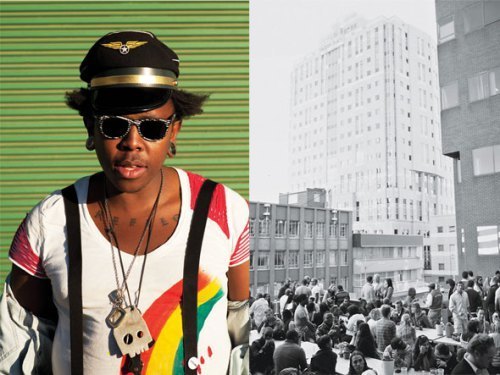

Africa is a Jockey

I want to share the story of an African Jockey, Sean Levey (in the photo above), but a blush biographical blurb about a rising star from Swaziland, particularly when his fresh face, a black face, is such a rarity in racing, would be like a cosmologist describing the universe without reference to dark matter.

I want to share the story of an African Jockey, Sean Levey (in the photo above), but a blush biographical blurb about a rising star from Swaziland, particularly when his fresh face, a black face, is such a rarity in racing, would be like a cosmologist describing the universe without reference to dark matter.

Levey is not some celestial trailblazer for African or jockeys from its diaspora, but a reminder of a heritage now barely discernible through race binoculars. In introducing the bright young thing that is Sean Levey, I will also consider his peers and look back at some of the black stars of the game. Black jockeys once had cache akin to today’s gold medal Olympians or Superbowl winning quarterbacks, but now the sight of a black jockey is as rare as the proverbial black swan. Who were the black star riders of a bygone age and how did we lose track of them in the racing galaxy? And what does it say about the nature of the sport today that so few black jockeys are aligned with the world’s greatest racehorses? Will the breakthrough of one African jockey change the global stakes for African and Diaspora riders?

When eighteen horses lined up in Europe’s richest race, Le Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe at Longchamp this past Sunday, there was not a black rider in the saddle. Similarly, when twenty-four horses parade in the Flemmington paddock before the world’s richest handicap, the Melbourne Cup, in early November, no one will be giving a black jockey a leg up. You can also be sure that when the bugler signals the start of the Breeders Cup at Santa Anita (what American racing enthusiasts casually refer to as “the World Championships”) next month, there will probably not be an African American jockey in the gate. It follows the same is largely true across global racing’s prestigious Group and Grade race cards, as well as among the less glamorous daily Handicap features that sustain the sport. It is a pattern. Some believe racing has a ‘race’ reputation. This may be unfair since racing has diverse participants and stakeholders across the globe. The rise of Indo-Caribbean and Latino jockeys in America being a compelling counterpoint. Female jockeys rode past the glass winning post decades ago. There seems to be few soccer-like racist incidents pulling on the sport, yet there remains serious inertia regarding the participation of black jockeys (and it would follow, black trainers and owners).

Sean Levey is vying to be champion apprentice jockey in Britain this year. He has the potential to win the world’s greatest horse races and change perceptions of the sport. It was a long way to Tipperary from Southern Africa for the teenage Levey. His parents’ decision to relocate to the county with the bluest grass in Ireland proving prescient for their prodigious child. Tipperary is home to Irish breeding and bloodstock giant, Coolmore. Sean’s father took up employment as an exercise rider for Ballydoyle, the racing arm of the concern, and soon Sean was hired as a stable lad. Between mucking out stables and riding pony races, Sean’s skills were quickly recognized and he was granted an apprenticeship under famed trainer, Aiden O’Brien. In 2006, Levey was chosen to ride in his first Group 1 race aboard Beauty Bright in the Irish 1,000 Guineas, a phenomenal booking for such a young rider. O’Brien’s trust in the rider extended further to France in 2009, when Levey got the ride aboard Cornish, a pacemaker for stable star Fame and Glory in the 2009 Arc de Triomphe. Last year, Levey relinquished the apron strings and reins in Tipperary and set out to make his name in British racing. He is now 2nd jockey at Champion Trainer Richard Hannon’s yard. Here Levey will surely pick up rides on Group rated horses and prosper. His career trajectory is now tight to the rail. You can bet on him winning big races in the future.

From left to right: Eduardo Pedroza, Johan Victoire and Adeline Gadras

Levey is not alone. There are other black riders ploughing the dirt and turf and trying to swoop in Europe, North America, Southern Africa and in the jockey clubs of South and Central America, though not as far as I know with any regularity in Asia, which as far as The Economist is concerned is certain to dominate racing in the decades ahead, with jockey clubs in the Middle East and Far East hosting the three richest races in the world. The most successful black jockey riding in Europe today is Panamanian Eduardo Pedroza. “Eddie” made his name in the rather unfashionable world of German racing, winning the German 1,000 Guineas, German Derby, and claiming the title of German champion jockey on four consecutive occasions. In the rather more rarified air of the French gallops, Johan Victoire wins occasional minor flat races, but only possesses a single digit win percentage rate. Adeline Gadras makes his living riding over fences in the French provinces. Before Sean Levey, Royston Ffrench had been the only black jockey riding regularly in Britain, and although he won the historic Cesarewitch Handicap in 1996, as well as two German classics, a German Derby and a German St Leger (a long distance gallop), and was champion apprentice in Britain in 1997, he has never won a Group 1 race at any of the esteemed English turf venues — a reflection, I would say, of the horses booked for him rather than his jockeyship.

Muzi Yeni and S’Manga Khumalo

In South Africa, the stalls handlers, stable lads and work riders are invariably black. Stable jobs are relatively highly paid and much sought after in South Africa. The weighing room, however, on the big race pay days remains largely the domain of whites–Afrikaners, English and or the occasional Irish pilot. Muzi Yeni and S’Manga Khumalo are local black riders who now seem best placed to buck that trend. Yeni rode Master Plan for his Group 1 victory in the Champions Cup at Greyville at the Durban July festival this year, while Khumalo rode the filly Dancewiththedevil to his first Group 1 victory in last year’s Oppenheimer Chesnut Stakes, Gauteng’s premier Weight for Age race at the Tuftfontein track in Johannesburg.

Black Zimbabwean jockeys are similarly overlooked, with white South African jockeys generally flying in to ride the big races in Harare. Last year’s running of the Castle Tankard Stakes, the oldest sponsored race in Zimbabwe, featured only two black Zimbabwean jockeys from a field of sixteen runners, while the Grand Challenge saw only three local riders given mounts at Barrowdale Park. It seems incomprehensible that a crowd of over 30,000 can gather at a racetrack in Harare, yet the best chance some local jockeys have of winning big is to enter the “Shop OK” tambola.

There are only a handful of black jockeys riding in North America. The most successful black jockey riding in the world today is probably Patrick Husbands (left). Husbands has been a top tier jockey in Canada for over a decade and has been leading jockey at Toronto’s Woodbine track on five occasions. His most spectacular achievement was winning the Canadian Triple Crown aboard Wando in 2003. Husbands was a prodigy, winning the Barbados Gold Cup in 1990 as a mere 16 year old. The Barbadian does take occasional rides at more prestigious US tracks, twice winning Grade 1 contests at Belmont and Keeneland, yet it is surprising his Canadian success has not earned him more rides in exalted stakes races in the United States. One could argue Husbands’s relative anonymity at US tracks is a case of location, logistics and transportation, but racing is now a truly global affair with top jockeys crossing continents over the course of a weekend for rides. Husbands’s one and only mount in the Kentucky Derby was when riding Seaside Retreat in 2006. (Stop Press: Husbands did not have a ride in any of Woodbine’s three biggest races this year. The Nearctic Stakes, the E.P. Taylor Stakes and the Canadian International Stakes have combined winning purses approaching US$2 Million. It is the one day of the year when the racing world focusses on Canada, but those who watched yesterday won’t have seen Husbands. The card was loaded with top riders from Europe and United States, however.)

There are only a handful of black jockeys riding in North America. The most successful black jockey riding in the world today is probably Patrick Husbands (left). Husbands has been a top tier jockey in Canada for over a decade and has been leading jockey at Toronto’s Woodbine track on five occasions. His most spectacular achievement was winning the Canadian Triple Crown aboard Wando in 2003. Husbands was a prodigy, winning the Barbados Gold Cup in 1990 as a mere 16 year old. The Barbadian does take occasional rides at more prestigious US tracks, twice winning Grade 1 contests at Belmont and Keeneland, yet it is surprising his Canadian success has not earned him more rides in exalted stakes races in the United States. One could argue Husbands’s relative anonymity at US tracks is a case of location, logistics and transportation, but racing is now a truly global affair with top jockeys crossing continents over the course of a weekend for rides. Husbands’s one and only mount in the Kentucky Derby was when riding Seaside Retreat in 2006. (Stop Press: Husbands did not have a ride in any of Woodbine’s three biggest races this year. The Nearctic Stakes, the E.P. Taylor Stakes and the Canadian International Stakes have combined winning purses approaching US$2 Million. It is the one day of the year when the racing world focusses on Canada, but those who watched yesterday won’t have seen Husbands. The card was loaded with top riders from Europe and United States, however.)

While Husbands remains a relative unknown outside Georgetown and Toronto, DeShawn Parker (left) is even more anonymous in his own country. Parker is one of about five African American jockeys currently riding in the United States. In 2010, Parker won more horse races at US tracks than any other jockey, an incredible achievement though barely recognized inside or outside of the sport. Bluegrass born and bred, Parker claimed those 377 wins at the relative backwater tracks in West Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania, a world away from America’s Triple Crown venues and other historic hippodromes, such as Santa Anita and Saratoga. Parker has since set about showing off his skill set at Tampa Bay Downs, which is probably a notch above the Mid West tracks he once owned, though still probably not quite the place to find the calibre of horse to propel his career further. Parker has never won a Grade 1 race in the US. It is his stated aim to win a Breeders Cup or a Triple Crown race, but it remains to be seen whether will ever get a ride in, let alone win such contests. Parker is now 41. Time is against him. Before Husbands’s appearance in the 2006 Kentucky Derby, the last black jockey to feature was Louisiana based Marlon St. Julien, who rode Carule to 7th in 2000. Before St Julien took that mount, there had not been an African American jockey in America’s premier horse race for an astonishing 79 years!

While Husbands remains a relative unknown outside Georgetown and Toronto, DeShawn Parker (left) is even more anonymous in his own country. Parker is one of about five African American jockeys currently riding in the United States. In 2010, Parker won more horse races at US tracks than any other jockey, an incredible achievement though barely recognized inside or outside of the sport. Bluegrass born and bred, Parker claimed those 377 wins at the relative backwater tracks in West Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania, a world away from America’s Triple Crown venues and other historic hippodromes, such as Santa Anita and Saratoga. Parker has since set about showing off his skill set at Tampa Bay Downs, which is probably a notch above the Mid West tracks he once owned, though still probably not quite the place to find the calibre of horse to propel his career further. Parker has never won a Grade 1 race in the US. It is his stated aim to win a Breeders Cup or a Triple Crown race, but it remains to be seen whether will ever get a ride in, let alone win such contests. Parker is now 41. Time is against him. Before Husbands’s appearance in the 2006 Kentucky Derby, the last black jockey to feature was Louisiana based Marlon St. Julien, who rode Carule to 7th in 2000. Before St Julien took that mount, there had not been an African American jockey in America’s premier horse race for an astonishing 79 years!

Such successes as achieved by Pedroza, Ffrench, Husbands and Parker, are praiseworthy. These few black jockeys are established professionals and bona fide champions. African jockeys like Muzi Yeni, S’Manga Khumalo, Kevin Derere and Irish accented Sean Levey now have global role models. Yet, it must also be said that in the context of world racing, the achievements of today’s African and Diaspora jockeys are relatively modest. Canadian, German and West Virginian racing are not generally viewed as being the most glamorous, no disrespect meant to those racing authorities, or indeed to esoteric jockey clubs like Barbados, Guyana and Mauritius, where black jockeys regularly ride winners.

The current racing scene contrasts greatly with a time long gone, a time when black jockeys bossed the biggest horse races, mostly in the United States. It’s often forgotten, but a black jockey, Oliver Lewis, won the first Kentucky Derby in 1875. In the first fifteen Kentucky Derbies, the winner was ridden by a black jockey on thirteen occasions. Success was not just restricted to the Blue Grass State. In the late 1800s and through the turn of the century, African American jockeys were winning from coast to coast and in some of the most prestigious horse races in Europe. Remarkable times. Here are a just few historical highlights.

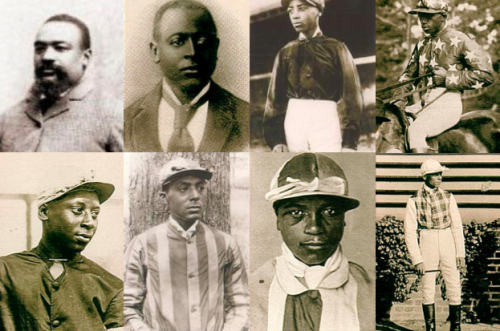

From left to right: Ed Dudley Brown, George Anderson, Alonzo Clayton, Tony Hamilton;

Jimmy Lee, Isaac Burns Murphy, James Perkins and Willie Simms

Ed Dudley Brown rode Kingfisher to victory in the Belmont Stakes in 1870. Brown went on to train two Kentucky Derby winners in Baden Baden in 1877 and Hindoo in 1881. Brown also trained and owned two Kentucky Oaks winners. In 1889, George “Spider” Anderson was the first African American to win the Preakness, riding Budhist to victory at the Pimlico track in Baltimore. Alonzo “Lonnie” Clayton became the then youngest jockey to ever win the Kentucky Derby aboard Azra in 1892. Lonnie also won two Kentucky Oaks in 1894 and 1895, as well as numerous stakes races in New York, including the prestigious Travers Stakes at Saratoga. Tony Hamilton won the Futurity Stakes aboard Potomac in 1890, as well two Brooklyn Handicaps in 1889 and 1895. Erskine “Babe” Henderson won the Kentucky Derby with Joe Cotton in 1885. Jimmy Lee won the Latonia Derby with The Abbott in 1906, but is probably best remembered for sweeping the entire race card at Churchill Downs on June 5th, 1907, a year in which he won 47 races during the Spring meeting, a record that stood until 1976. Isaac Lewis won the Kentucky Derby with Montrose in 1887. Isaac Burns Murphy was the first jockey to win the Kentucky Derby on three occasions, with Buchanan in 1884, Riley in 1890 and Kingman in 1891. Murphy remains the only jockey to win the Kentucky Derby, Kentucky Oaks and prestigious Clark Handicap in the same year. He managed 628 wins in 1,412 races, a career win percentage of 44%, a statistic no jockey will ever match.

And the hits kept on coming. James “Soup” Perkins was America’s Champion Jockey in 1895 with 192 wins, a year he also won the Kentucky Derby aboard Halma. Georgia’s Willie Simms was the only African American jockey to win all three Triple Crown races, winning the Kentucky Derby in 1896 and 1898, the Preakness in 1898, and the Belmont in 1893 and 1894. Simms’s fame also extended to British tracks were he was a notable presence in the 1890s, introducing the “short” style of riding, leaning far up the neck of a horse, revolutionizing the art of race riding in England and Europe.

Simms was not the only African American jockey to have had an impact on European racing. Jimmy Winkfield (left) was another. Winkfield accomplished the rare feat of winning back to back Kentucky Derbies with His Eminence in 1901 and Alan-a-Dale in 1902. Known as the King of the Chicago tracks, Winkfield also won the Latonia Derby, New Orleans Derby, Clark Handicap and Tennessee Derby, but it was in Europe where he had the biggest impact, winning a whole host of classic races including the Russian Derby (four times), Russian Oaks (five times), the Warsaw Derby (twice), the Prix President de la Republic and the Grand Prix de Deauville (two of France’s most renowed races, then and now). I cannot begin to do justice to Jimmy Winkfield’s legacy here, but those interested in the life of man who witnessed lynchings, had his American career halted by Jim Crow laws and ended up in Czarist Russia with white man as his personal valet, then I recommend Joe Drape’s tour de force, Black Maestro: The Epic Life of an American Legend.

Simms was not the only African American jockey to have had an impact on European racing. Jimmy Winkfield (left) was another. Winkfield accomplished the rare feat of winning back to back Kentucky Derbies with His Eminence in 1901 and Alan-a-Dale in 1902. Known as the King of the Chicago tracks, Winkfield also won the Latonia Derby, New Orleans Derby, Clark Handicap and Tennessee Derby, but it was in Europe where he had the biggest impact, winning a whole host of classic races including the Russian Derby (four times), Russian Oaks (five times), the Warsaw Derby (twice), the Prix President de la Republic and the Grand Prix de Deauville (two of France’s most renowed races, then and now). I cannot begin to do justice to Jimmy Winkfield’s legacy here, but those interested in the life of man who witnessed lynchings, had his American career halted by Jim Crow laws and ended up in Czarist Russia with white man as his personal valet, then I recommend Joe Drape’s tour de force, Black Maestro: The Epic Life of an American Legend.

Jim Crow curtailed the careers of African American jockeys in their prime and pomp. Horse racing in America has never been the same. Hollywood has told plenty of romantic horse stories and great horses like Sea Biscuit and Secretariat are now immortalized, ‘On Demand’, but the story of the great African American jockeys, the horses they rode on and how they once ruled the Sport of Kings remains a niche narrative. Black South African jockeys never reached the heights of their American cousins, but what achievements there may have been from the first races Khoikhoi riders rode against British officers at Green Point in 1795 to the tracks that sprouted up after diamond and gold rushes and wool booms have been buried.

What Jim Crow could do, ditto the South African Jockey Club, which banned participation of non-whites in racing, except as grooms, in the 1920s — decades before Apartheid. It seems the residual effects of such shameful bigotry have continued to handicap the progress of black jockeys to this day. Sean Levey now has the potential to replicate the achievements of the great Isaac Burns Murphy, Willie Simms and Jimmy Winkfield. This is largely because of a combination of family decisions, his skill and determination and a little luck. One always needs a little luck in racing. The prospects of the Swaziland jockey have not been enhanced because the industry in its various manifestations stepped up in any significant way to do more for black riders. If they had have done, there would be many more black jockeys racing at the highest levels in Britain, France, South Africa and the United States. It is also fair to counter and say most jockeys of whatever ethnicity have a hard time finding mounts on the very best racehorses. It is a very competitive business.

All of which is not to suggest the racing establishment is racist, but perhaps aloof, absent-minded and disconnected in some way from its own black history and from a community that can once again contribute so much to the sport. Racing jurisdictions cannot force owners and trainers to choose jockeys, and no one is calling for some politically correct allowance, but racing’s constituents can and should do more. Mark Casse, Andreas Wohler, Aiden O’Brien and Richard Hannon are establishment trainers who have given young, gifted, black jockeys opportunities. Others should consider how they too can make racing more inclusive and appealing to wider audiences.

In the meantime, Sean Levey has a lot of weight and history to carry.

#Tintingate (in Sweden)

On September 25, one of Sweden’s most prestigious national dailies blew up an article on its front page about cultural director at Stockholm Culture House Berhang Miri (a Swede of Iranian descent) reshelving Hergé’s Tintin books because of their perceived colonial taint, generating heated press and internet debate. Surprisingly, the furor rages on three weeks later, which if you also include the discussion about Stina Wirsén’s film character Lilla Hjärtat marks a very unusual month of the Swedish public sphere discussing historical racist stereotypes and colonial traces in children’s literature.

We asked Nathan Hamelberg, member of The Betweenship group (which probes racist structures from a young, mixed-heritage perspective), to explain the discussion and its wider implications in Swedish society.

What is #tintingate? How did it develop?

To an extent, it’s a part of a larger discussion that’s been ongoing for at least a year, in which racism has been discussed more openly, but where the exceptional thing has been a specific focus on the trivial places where racism has appeared: on candy packaging, as an artist’s cake, and so on.

Then the whole thing exploded when a major newspaper wrote about the artistic head of a youth culture centre moving the Tintin books to an adult section, after which the negative Twitter reactions came almost immediately. Some were opposing it because they claimed it was censorship. Others were saying it was counter-productive, that Tintin wasn’t racist. And of course there was a third, not worth responding to but very vocal group who basically were just provoked by the fact that a Swede of Iranian descent was allowed into the media spotlight at all. On the other side, anti-racists generally were standing up for Behrang, claiming to see the problematic traces in the Tintin books.

What’s interesting is that there appears to have sprung from what could be seen as a rather marginal discussion a much broader shift in who gets to have the privilege of defining what is racist or not. A lot of non-white voices have been permitted to be heard in the biggest media for the first time. That is amazing to me.

What are your thoughts on the arguments presented?

I think there are problematic exaggerations and generalisations on all sides. No-one is really advocating using censorship as a simple solution, which commentators seem to claim is what’s happening. I don’t event want to tell you all the nasty things Behrang’s decision has been compared to. Truth is, with libraries there’s always a decision of what books end up being placed on which shelves, what kind of literature is promoted, and which books ends up in storage.

The whole thing became unnecessarily polarised. For all the lofty expressions about freedom of speech, we have never applied those principles to children’s literature the same way. I wish we could have a more nuanced, ongoing discussion about libraries, selections and children’s texts, because these are important issues.

Some have claimed that the whole thing was a journalistic set-up, blowing up a regular reshelving decision by an inexperienced middle manager in order to generate precisely the debate that occurred.

I think there’s some truth in that. The newspaper, Dagens Nyheter, was somehow goading Miri to make a brash statement and it became so incendiary because of it. Part of the strength of the reaction was a direct result from that article, with people believing that Berhang has a carefree attitude towards censorship.

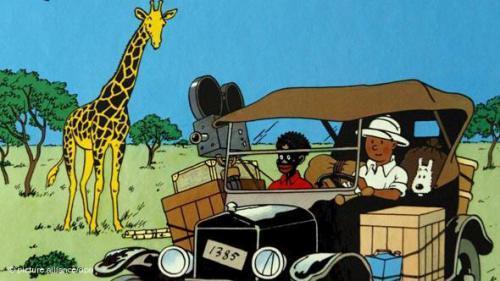

Do you personally think the Tintin books have problematic colonialist elements to them?

I think there are several layers that are problematic, yes. First of all, there are the early books that are blatantly and openly racist, like “Tintin in the Congo.” As a second layer, there are things that would be considered racist today but that were quite normal in Hergé’s time. This can be apparent to critical-minded adults, but not to the pre-teens who this particular library is made for. Thirdly, there’s the very fundamental problem that even the anti-racism in the books is typical of Hergé’s time and its racial hierarchies. The anti-racist effort in the adventures of Tintin is portrayed as a sort of civilatory white man’s burden — a knightly, gentlemanly missionary activity. At the time before decolonisation this may have appeared normal, even radical to an extent, but today it’s at best infantile and at worst derogatory. It exemplifies the essential problem with white anti-racism in general, certainly the problem with anti-racism in Sweden.

That said, and to complicate matters, I’m also a fan of Tintin.

Nathan Hamelberg

How would you connect this discussion to a wider debate on the problems of literature with a colonial heritage?

There’s the standard argument, almost playing the devil’s advocate, that it’s necessary to keep these colonial depictions “for an educational purpose”. But necessary for whom? Do we need, in our current time, to have racist imagery stockpiled on us again and again? What kind of message does that send to children? What kind of message does it send to those depicted?

And if these “educational examples” are so important, why does it appear as if the same white people who are advocating for them have learnt nothing from them? I’ve seen, for instance, Prisoners of the Sun being referred to as a shining example of Tintin’s anti-racism. And yet it portrays Andean Quechua people as incredibly superstitious and practicing human sacrifice, with only the fully westernised Quechua boy Zorrino shown in a positive light. The native people not siding with the whites are made out as evil, completely ignoring the horrors of colonial crimes. And of course Tintin is the white man to the rescue… And these people are supposed to have learnt something from being critical to racist literature? Honestly, it’s as if Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom were to be considered a fair representative of Hindu culture.

It’s also problematic that we need to continually review and respond to the books that are obviously racist. I’m more interested in the works that are in between, the ones that can be kept, and the question of how we can guarantee that there will actually be a critical discussion around them. I really don’t think it’s so strange to take something like Tintin away from children. We are perfectly ready to make this sort of appraisal when it comes to gender roles, or sexuality, or the negative stereotyping of poor people in very old books, but I think the problem here is that it’s seen as a group concern, something internal to Afro-Swedish people. The wider implications around children’s rights not to have their group depicted as a racist stereotype are missed. And honestly I don’t know which white parents would want their children exposed to racist imagery anyway!

In the Anglo-Saxon and Francophone world the discussion around Tintin’s colonial heritage has been ongoing for a lot longer, with Tintin in the Congo for instance not published in English until the 90s because of concerns about its stereotypical, racist depictions. How is Sweden different here?

Sweden’s national identity is interesting. We’ve got this view of our country as being fundamentally anti-racist at a deep level. This has almost become the big official Swedish ideology. And yet our anti-racism is different from that of the UK, France or the United States because their anti-racism has been framed against a backdrop of an awareness of the crimes of colonialism, and as a response to them. Sweden has a colonial history as well. It participated in the slave trade and was the last of the Western European countries to abolish slavery. Yet people here know almost nothing about it! It’s just a note in history textbooks, and there are almost no efforts to commemorate the victims.

Up until the Second World War, Sweden was a pioneer state when it came to eugenics and scientific racism, and continuing a programme of forced sterilizations way after. I had a discussion with my uncle — Sierra Leonean like my father but living in the Netherlands — and he was shocked to learn that the left-leaning social democratic country he held as an ideal was actually sterilizing citizens as recently as in the seventies. I had to correct him, “Harold, Sweden is actually still sterilizing transsexual people in this very day and age…”

And at the same time: after WW2, which left Sweden untouched, the increased economic prosperity and the large built-up surplus led to an almost 100% reversal of self-image, with Sweden suddenly wanting to appear as a shining beacon of foreign aid and international solidarity. Now, I’m not saying there isn’t some good reason for this. For instance, the Swedish state secretly and illegaly supported the ANC (of South Africa) economically when no other western countries did — when there seemed to be little hope for Apartheid ever ending. Sweden helped refugees flee Chile after Pinochet’s coup there. And at times we’ve had the most liberal asylum laws in Europe. Many Vietnam War draft dodgers came here, and Sweden was (perhaps together with Canada) one of the few western countries where criticism of the Vietnam War moved from the fringes of the debate to its mainstream.

But what actually changed on the ground is a different matter. There has remained a systematic silencing of non-white and dissident voices that questioned the official truths. And the official anti-racist line (with its generous foreign aid) contrasted and coexisted with a continual state racism against national minorities, especially the Roma, with forced sterilizations, bans on settlement a common practice. And a strong social segregation along racial lines continued to exist.

Sweden is a country with a strongly enforced sense of homogeneity and a strong central political power. We never had to compromise to share power with regional minorities as Britain or Spain had to, inscribing rights to non-Castillian or non-English groups. Comparatively, Sweden’s national minorities — Jews, Sami people, Roma, and Finns (which is a very large minority indeed) — were very slow to receive their rights. Instead, there’s been a pressure to conform, a passive aggression directed at those who do not comply with the official line of “when in Rome”. Minorities and immigrants are supposed to be grateful for being allowed to stay here — a claim which ignores that Sweden has played a role in sustaining the conflicts that led many to seek refuge here in the first place, selling weapons to both sides in the Iraq-Iran war under the table, for instance.

“Tintin in Congo – the IKEA version” by Åke Forsmark.

Do you think Sweden is finally waking up to its colonial heritage then?

I’m not sure. In a sense, this debate is like a childhood disease: while having it earlier would have resulted in milder symptoms, the way it’s happening now is quite difficult. So I don’t think things will change in the short term. Still, the fact that non-white voices are entering the debate is amazing, and necessary. The cultural establishment in Sweden has been lagging behind on this issue in so many ways, even compared to the rest of society. For instance, a senior sports commentator recently was caught on tape calling an African footballer a “darkie”, and the initial reactions were miles ahead of the naive #tintingate discussion. The widest implications of this whole affair must be about the cultural establishment. It needs to be de-segregated! It can no longer be the case that only white voices are allowed to define what is and isn’t racist.

If Sweden is so ignorant about racism, why did this discussion start now?

It’s a series of things. The “war on terror” has fuelled a lot of islamophobia. Post 9/11 there’s been a lot of room for a populist, xenophobic right, as we now see in Sweden, with the Sweden Democrats in parliament and with violence against Roma and against black people. The economic crisis has fuelled this as well. The fact that these movements have become so prominent has led to a lot of mainstream politics agreeing on the presumptions of their world view, a division of us-and-them, a discussion based on racial hierarchies. Anyone who questions these hierarchies is punished, and that is what we’re seeing here.

Do you feel the conversation is likely to continue after #tintingate?

Not necessarily as much in the spotlight. Perhaps in a more low-key way, and mostly in critical circles. After all, to some extent, that this has happened right now is largely a fluke. One thing we’ll see more of is a discussion of these issues among feminists, who have had their own vicious attacks against them and whose more left-wing elements are strongly rooted in anti-racism. In this conversation, much of the most resolute opposition has come from non-white feminists.

October 14, 2012

“This is My Route!” Race, Entitlement and Gay Pride in South Africa

By T.J. Tallie and Maria Hengeveld

It’s been a week since the now infamous events of the Joburg Pride Parade, where the organization One in Nine attempted to disrupt the parade in order to protest both systemic violence targeting black lesbians in South Africa and the commercialization of the Pride event itself. The heart of the protest, calling for one minute of silence for black queer victims of violence, was met by animosity and additional violence from the predominantly white attendees. Reading media reports of the event itself, we are reminded of the complexities of Marikana; in the days and weeks following the mining massacre, there was no clear or easy story, but rather multiple histories of capitalism, violence, state repression, and brutality, each jostling against each other and refracting in confusing new realities. Yet as Brett has stated on this site, this “was not a crime and a tragedy on the scale of Marikana. It was not even startling and unusual.” But it was gripping to see it captured so vividly on film, where both the violence and fearful, misguided claims of legitimacy are revealed in such simple, disheartening ways.

One of the most salient moments of the Pride exchange occurs in the video when white organizer Jenny Green shouts “This is my route!” at the protestors; yelling with confusion and anger from her car. There is, perhaps, an understandable sense of anger at someone’s meticulously planned public event being ‘ruined’ by the arrival of unexpected bodies. Yet the confusion and incredulity that anchor that angry sentence say so much more. “This is my route!” is a claim to space, and to authority and legitimacy on the highly politicized streets of Johannesburg, and South Africa in general. The stakes are not merely over the timeliness of organizing and schedules on a springtime march through the city; rather, that simple sentence reveals much about claims and counter claims of legitimacy in a postapartheid South Africa, made infinitely more complicated through the politics of sexuality and LGBTQI rights. Who is allowed to claim the legitimacy and authority to plan the “route” in question? In an ostensibly post-apartheid South Africa, where political legitimacy no longer rests in the hands of the white minority but the economic and social inequalities still weigh highly in their favor, these questions loom large.

South Africans sympathetic to the One in Nine Campaign have viewed the protest as a legitimate social critique of Pride’s evolution from its dangerous and politically powerful beginnings in 1990 under the apartheid regime. In particular, filmmaker Gillian Schutte, photographer Nadine Hutton and journalist Charl Blignaut have been deeply critical of the racial assumptions and entitlements that have produced such angry, defensive responses from Joburg Pride Parade supporters, most of them white. Schutte pointedly asserts, “The violence and hatred shown to the One in Nine protestors was another example of white entitlement. Not a jot of embarrassment was shown by the abusers.” In her assessment, Hutton made explicit the consequences of white entitlement at the Pride Parade: “the face of this year’s gay pride was ugly and racist and violent. This is the daily horror of black queers.” Schutte adds that the violence towards the black protestors threatened by Green (who revved her car at the protestors amid calls to ‘run them over’) and directly enacted by fellow organizer Tanya Harford, served to “show just how little most white people empathise with black issues, black bodies and black emotionality. The inherent mantra of ‘white is right’ was written all over this event.” Blignaut decried the “privileged white queers who want to place us all in a neat, homogenous box,” allowing a “queer apartheid” to slowly develop within Pride celebrations.

Writing for South Africa’s Daily Maverick, Rebecca Davis argues that the racial lines both in South Africa—and particularly within the LGBTQI community—are enduring and powerful. The article privileges One in Nine member Kwezilomso Mbandazayo as a major source, and reports some of her (and the group at large) concerns faithfully: that the Joburg Pride board is exclusively white, that Pride has become a depoliticized, commercialized space existing only as a social celebration without any social power or purpose, and that all of this is taking place in a moment where queer black people face daily threats of violence that are completely ignored by the Parade.

As Davis’s piece (and Brett’s post on AIAC) make clear, the politics of white supremacy and resistance have been stamped upon South Africa’s LGBTQI history as much as everywhere else within the country. The utter insularity of many white South Africans from the daily realities experienced by over eight-tenths of the population from whose outright oppression they benefitted collectively is threaded through the history of LGBTQI struggle in South Africa. The largely white dominated GASA (Gay Association of South Africa) refused to denounce apartheid, and its leaders publicly equivocated when black gay activist Simon Nkoli was jailed by the apartheid state, showing the very thin level of queer solidarity within the country.

The media analysis and the video footage from Saturday’s event both illustrate an obvious point: the assumption propagated by the Pride Parade that people possessing a shared experience of oppression by heteronormative society will unite in solidarity is at best a naïve illusion and at worst a dangerous deception, as the protestors attacked on Saturday can surely attest. Living in South Africa, we have observed a sense of ‘black rights fatigue’ playing at the edges of many forms of white political discourse. The idea that the systemic exploitation and disadvantage of the country’s majority should be ‘fixed’ after two decades, or can be solely assigned to the incompetence of the ANC is a convenient myth that justifies this dangerous white entitlement. It is used by white South Africans weary of having to feel guilty or even think about the entitlements that have led them to such extremely different circumstances from those dwelling in the townships (or lokshini, as a white Pride marcher derogatorily referred to the supposed homes of the One in Nine protesters).

Yet as we have watched the video over and over, that sentence still haunts us. “This is my route.” The fraught politics of belonging rear their head in those four words. For all of the assertion of power and threats of violence behind Green’s words, she is trying, desperately, to assert that she belongs, that she is control, and that she has a place in South Africa. Yet the black bodies lying in front of her on that Rosebank road tell her that she does not, should not have the power to draw the routes she desires. The bodies in the street attempt to crack a racialized sense of entitlement that allow Green and others like her to pretend they are not part of the larger forces that have turned a historic political demonstration into a commercial party, and continue to obscure the lived terror of less privileged members of her own ostensible ‘community.’

October 12, 2012

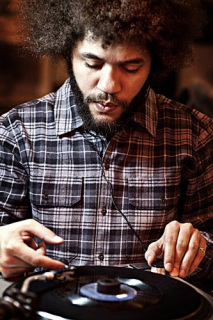

Friday Bonus Music Break

Nigerian-Swedish pop star Dr Alban features in this new St. John’s Dance video above. Swedish-Finnish-Gambian (yeh) rapper Adam Tensta is the guy behind the group. (Tensta started with more straightforward rap, but has since found a slightly different sound, as illustrated in this Nollywood-influenced video.) Next, more common Nigerian pop:

Your weekly dose of kuduro courtesy of JD, Nagrelha and Rei Panda:

Jean Grae created this video for ‘Kill Screen’:

A Sauti Sol & Spoek Mathambo collaboration:

Via okayafrica: Octa Push’s ‘Mambowrp’.

A dramatic video for new music by Nëggus (repping for Togo):

From Grahamstown, South Africa, the Wordsuntame duo:

A down-beat version of the closing song of Terakaft’s new record Kel Tamasheq (from Mali):

And a Nomadic Wax moment with Kisangani (Congo) artist Alesh:

Those Nigeria-Finland-Sweden-Gambia connections? That’s Mikko. We’re back on Monday.

“To Bring the Beat Home”: Soul Power in Kinshasa

The opening scene: Soul Brother No. 1 dressed in a skin tight matador-cum-gimp suit, drop-kicking the mic, screeching, roaring, galvanising a Congolese crowd into pure hysteria, while chanting ‘I’m black and I’m proud’, so camp as to be almost melting. This is Zaire ’74, the little known concert to accompany the mega-fight Rumble in The Jungle between Mohammed Ali and George Foreman, and the subject of Jeffrey Levy-Hinte’s Soul Power (2009), now released on DVD by Eureka Video. It’s a riotous, uplifting film. It dazzles in its capture of the glitter and bare-chested kitsch of the 70s black soul acts and their ‘homecoming’ to Kinshasa. Masterfully edited from the off-cuts of Leon Gast’s Oscar winning documentary When We Were Kings (1994), Levy-Hinte’s devotion to the material is palpable, and yet there remains a discrete critical distance.

The greats of 70s soul were there: BB King, Bill Withers, James Brown, Miriam Makeba, Sister Sledge, The Spinners, Celia Cruz and Fania All Stars…. Soul Power captures a moment in African-American music during the 1970s that was exploring its own associations, testing its boundaries. Scenes in a hotel dining room in New York, the night before departure, fizz with the furious excitement of organisers to ‘bring the beat home’; the almost frantic determinism of the performers to re-locate blackness as authentically ‘African’ is the subject of every exchange on film.

Muhammed Ali’s philosophizing runs as a meta-commentary throughout the film, as Levy-Hinte’s editing allows for shots of Ali’s political freestyling to continue at length without cutting; “I thought the Congo was a lot of jungle and little rough mau mau’s moving around attackin’…some people scared to come over here. It ain’t so bad. New York is more of a jungle that here.” At times, the film seems to capture Ali in a spoken-word trance, freely exploring and (re)formulating his ideas, live.

“Black Power is sought everywhere, but it is already realised here in Zaire,” reads a billboard at the concert’s stadium ground, which cuts to a brief shot of Mobutu Sese Seko’s portrait on the side of a building, leopard-print cap at its now iconic jaunt. The original footage seems to lack any interaction with Kinshasa as a place, instead reflecting the bubble of political rhetoric that the performers created for themselves, but didn’t share with their ‘brothers’ on the streets outside. By 1974, Mobutu already far into a violent campaign of ‘authenticity’ aimed at eradicating all European influences in Congolese culture but which inevitably frayed into violence towards his colleagues too, and which by ’74 had already morphed into untrammelled dictatorship. But acknowledgement of this, or even a hint, is completely absent from Soul Power, perhaps a sharp indication of the murky relationship between the US and Mobutu’s regime at the time.

But apart from a lack of political content, which through its absence becomes a another (silent) meta narrative of the film, Soul Power is above all an astounding document of soul. Bill Withers gives a spine-tingling performance, an almost masochistic rendition of ‘Hope She’ll Be Happier’; he tests himself emotionally and physically on stage, humming on the verge, holding a note for what seems an eternity while beads of sweat bulb onto his forehead. Cut with James Brown’s impish energy, Soul Power manages to capture the best of 70s black soul at a moment when it was exploring itself politically, emotionally, while keeping a critical distance, allowing the whole motivation for a musical ‘homecoming’ to be investigated.

October 11, 2012

Soukous for Francophonie (and for Kabila)

Big concert this week, October 10, in Kinshasa to honor the 2012 Francophonie summit. Performances by Papa Wemba and Werrason with their groups have already been posted online. Also on the program were Mbilia Bel, Tshala Muana, Nyoka Longo, Koffi Olomide and other titans of soukous and ndombolo, plus a few artists from other countries. Watch the clips: great fun. But the roster replicates the schism that has occurred in Congolese music over politics – specifically, whether to endorse President Joseph Kabila, and gain from official patronage; or whether to oppose him, either from outside the country, where numerous soukous veterans have sought shelter, or domestically, in the largely hip-hop-driven Kinshasa underground.

Indeed, in the run-up to the election of November 2011, which returned Kabila to power over perennial opposition figure Etienne Tshisekedi against a backdrop of violence and observed irregularities, a great many musicians had come on board with praise songs exhorting people to vote for the president. Here’s Olomide, for example, with this spoken intro: “Parce que son amour du Congo a fait ses preuves, Koffi chante Joseph Kabila” (“Because his love for Congo has been demonstrated, Koffi sings for Joseph Kabila”). The song sounds great, of course. So do the others in this terrific compendium on the Congo Siasa blog, with videos from Papa Wemba, Tshala Muana, Werrason and others, and an interesting discussion in the comments. (There’s another rich conversation on the same topic on this message board.) Whatever the sincerity of their political sentiments, artists who line up behind Kabila stand to benefit from patronage and opportunities like this gala concert.

This has not gone over well in the Congolese diaspora, where artists linked to the government have seen their concerts boycotted or their venues blockaded when attempting to perform in Belgium, France or elsewhere. (There’s a good summary here, in French.) These actions stretch back to 2005, when demonstrators succeeded in shutting down a JB Mpiana concert in London. Opponents have resorted to violence as well: Werrason, for instance, was ambushed in 2005 in a Brussels restaurant, and again in 2011 in a Congolese restaurant in St.-Denis, outside Paris. Although some of the more extreme incidents have given rise to controversy over motives and perpetrators, the self-styled “Combattants,” who want to shut down overseas performances and sales of artists they view as collaborators, maintain a proud presence online. They document their actions, which can be found by searching “combattants Congo” on YouTube or DailyMotion; here’s an example, where Combattants in Paris last year sought to have CDs by Olomide, Werrason and Mpiana removed from the shelves at the FNAC shop on the Champs-Elysées, and later in the video are seen handing out pirated copies of these artists’ discs, each stamped “COLLABO” on the front.

When I met the great soukous guitarist Diblo Dibala in New York recently, he mentioned the Combattants: “They’re shutting down the artists who are based in Congo, the ones who sing the praises of the government and who eat with the government,” he said. Dibala, who has been based in Paris for many years, said he keeps away from politics, but at the same time was clear about his view of Kabila and the recent election. “Those weren’t even elections,” he said. Dibala travels back to Congo, but won’t perform there until the situation changes. When it does, he said, he hopes all the expatriate artists can return home and play a concert together. “We don’t want to go and endorse this government. But as soon as things change we’ll be the first ones there.”

Of course, there is plenty of dissident music being made in Kinshasa right now. It largely takes the form of hip-hop, as documented for instance in this recent round-up by Radio Netherlands Worldwide. But what separates this youth underground from the soukous and ndombolo establishment, whether those on stage at the Francophonie concert or their opponents abroad, isn’t just politics, but the change of social outlook that comes with a new generation.

P.S.: Readers in New York City may want to check out “Congo in Harlem,” a very strong series of films and events that runs October 12-21.

The Indelible Mark of the Mbira

The multi-named thumb piano is quite an important foundational instrument for contemporary music all over the world, although it’s perhaps not always recognized as such. In Congo, colonial era missionaries banned the instrument from their services, saying that its association with traditional spiritual practices sullied the sacredness of the choral music they were adopting to the musical cultures of the people they sought to convert. But, the instrument lived on in Congolese pop as guitarists in Kinshasa adapted the style to their finger picking Cuban-son infused Rumba. The instrument has also travelled far and wide beyond Africa. I’ve seen versions of the thumb piano in historical photos of Jamaican Mento bands, and it is common in Latin American musical history as well. I wouldn’t be surprised if a few thumb pianos made their way to the American South helping to influence the blues guitar style that originated there.

Today in the wake of the international stardom of such groups like Konono N˚1, the thumb piano has made somewhat of a resurgence in contemporary pop music. I tend to be wary of the exoticism that sometimes accompanies the flash popularity groups with strange traditional instruments, so it’s funny to me how much that same instrument has figured so centrally in my life recently.

For the past week I’ve been touring with Sierra Leonean Kondi virtuoso Sorie Kondi. He and bandmate Ibrahim finally arrived at my house last week after his Sierra Leone based producer Luke Wasserman and I spent several months working to bring Sorie to tour in the United States. Our initial intention was to structure the tour around the SXSW music festival in March, which we raised money on Kickstarter for, but the timing didn’t work out since the U.S. Immigration office waited until the last second to grant Sorie his visa. But, I have to say the wait was worth it as I’ve been having such a wonderful time with the Sorie Kondi crew this week.

My relationship with Sorie Kondi began one morning in Oakland, California when I saw a link to the video for his song “Without Money No Family” sent by my friend Banker White. I knew instantly that I wanted to remix his song: firstly because the sound of the recording was so sparse ready to remixed; secondly because I knew that a larger audience than those interested in Sierra Leone (literally 5.5 million of us) needed to know about the musical genius of this man; and third the intelligible English lyrics carried a social message that I knew audiences in the North could understand (and perhaps transcend ideas of exoticism). I found the album available on iTunes, downloaded it, remixed the song, and passed a rough version of it to a German DJ, who put it in a mix.

The unfinished draft of the remix sat on my hard drive for a couple years, until I received an email from Luke, who had been working with Sorie since 2007. Luke had helped Sorie record his album Without Money No Family, and was now looking for other opportunities to promote his music. They had just finished recording his second studio album at Big Fad studios in Freetown. I thought about remixing the album or coming to Sierra Leone to work on some original tracks with Sorie. Luke mentioned he wanted to bring Sorie to the U.S. for a tour, so at that moment the wheels to bring Sorie Kondi to America were set into motion. I finished the “Without Money No Family” Remix, put it on my release African in New York, and one kickstarter campaign, a couple visa applications, and a trip false start later, Sorie Kondi is in America.

So far we’ve played shows in Washington DC and Philadelphia where Sorie and Ibrahim wowed audiences with their Sierra Leonean version of cultural dance music. The event in DC, hosted by Mothersheister, DJ Rat, and DJ Underdog at Tropicalia was warm and welcoming, and the crowd danced the night away to Sorie’s Kondi and his bass box boom pumped up to sound like a House music club. The show in Philadelphia really made me sink into thoughts of blurring of the lines between traditional, folk, or world music and contemporary pop, electronic, or dance music. The venue was an old church in West Philadelphia, whose acoustics made the Kondi reverberate off the walls and back into itself creating waves of tones that sounded like the rising of arpeggiated synths. There was an impressive amount of sound coming from that small wooden box.

Beyond the amazing musical aspects, the cultural exchanges that happened on the road were inspirational in themselves. One highlight of the gig hosted by the Tropicalismo crew and Sonic Diaspora in Philly, were the exchanges that happened between the Sorie Kondi team and Colombians Explosión Negra who performed and partied with us late into the night on Saturday. While neither Sorie Kondi nor Explosión Negra could communicate through spoken language, and this separated the crews in every other space, on the dance floor it was a Champeta Soukous, Temne Techno, Chirimía Soca dance celebration! Not to harp too much on the cliché but it was really amazing to be part of a such a moment where the universality of music was so evident. I really believe that it is during these types of moments that this new lightweight and mobile, do-it-yourself global bass club scene (or whatever you want to call it) is at its best.

Sorie Kondi is in New York this week, and if you are a music lover of any genre, from folk to Techno (or like me, the amalgamations that blur the lines between them) then you don’t want to miss his performance at Public Assembly in Williamsburg Brooklyn this Saturday October 13th. We’ll be celebrating the release of Lamin Fofana’s Africans Are Real project (which I have a remix on as well) who will be performing live alongside Brooklyn rappers Old Money, and DJing will be Binyavanga Wainaina, Clive Bean, GiKu, Matt Shadetek, and myself:

If you miss that one, or you aren’t in New York this weekend check all of his tour dates on Vickie Remoe’s site.

The other major way the thumb piano has appeared in my life is in the Zimbabwean form, known as the Mbira, via Shabazz Palaces beat maker Tendai Maraire. Talk about pushing the boundaries between traditional and contemporary, Shabazz Palaces have been able to challenge music fans of all backgrounds with their mind blowing videos, inspiring live performances, and futuristic Hip Hop beats wrapped around Tendai’s skilled live percussion and Mbira playing. Sometime this summer Tendai called me up and said that he wanted me to do a mix for him after hearing some of my work. Just by coincidence the first mix of mine he listened to started out with the a plinking Mbira, and he said he knew right away that he knew he had found the DJ to work with.

After we discussed details of the project, I really took up the challenge to try and find any Mbira playing in the old records I have collected along the way, and may have not listened to that closely. I think the most exciting realization to make was that one record that I had once bought in the discount bin at Amoeba records in San Francisco (and later saw on sale in the premium section for $60 — I wondered, and still wonder why the vast price difference for the record) was in fact a record by Tendai’s father Dumi Maraire. This made both father and son’s music really come alive with brilliant historical context. The record I have seemed to have been from a live performance in Seattle a little after or around the time Tendai was born. The label on the record also describes the record as “Zimbabwe,” which is interesting because it was recorded at a time when Zimbabwe was still called Rhodesia. With that realization, the military-tinged images that Tendai paints in his lyrics suddenly start to fall into place for me:

When I try to do mixes I always try to base them around a central theme or concept. This one proved a challenge for me since I don’t know as much about Southern Africa as I do about West Africa. But I do know that music and a contentious politics from Mozambique to South Africa to Zimbabwe to Angola are intimately intertwined in a history of struggle against colonial rule and state-based violence. So, being an outsider to all that, all I could do was try to connect the dots across national boundaries to show how the cultures (and by extension the struggles) of Southern Africans are very much intertwined. In my record collection, I was able to find a bunch of Mbira related songs from across Southern Africa including Bonga (Angola), the Kasai All Stars (Congo), and DJ Sbu (South Africa). Of course there are plenty of Zimbabwean tracks from the likes of Thomas Mapfumo and Tendai’s father, Dumi! Lastly, I just included some of my favorite songs, like the ones from Khaled and Yossou N’Dour, that I thought fit well with Tendai’s original productions, which he in turn remixed to amazing results!

10 African films to watch out for, N°6

One of the reasons recently given by members of the local advisory committee to the responsible authorities for withholding much-needed subsidies to the Africa film festival in my home town was the question whether enough films were available. Yeh. Here are another ten films we’ll be looking out for.

First, ‘The Golden Calf’ by Hassan Legzouli (trailer above) in which 17 year-old Sami gets sent by his father to a village in the Moroccan Atlas mountains “to make a man of him”. But, says the plot, “all Sami wants is to go back to France before his 18th birthday so he can get French nationality and get back together with his girlfriend. Sami and his cousin come up with a plan to steal an ox from the Moroccan royal family’s ranch and sell it to pay for the crossing back to France.” A timely film.

Next, not quite new but I still haven’t had the chance to see Deron Albright’s police drama ‘The Destiny of Lesser Animals’, set in Ghana:

From Mauritius comes ‘The Children of Troumaron’. Troumaron, an area in Port Louis, forms the backdrop for a story about four youngsters. The film is an adaptation of Mauritian author Ananda Devi’s novel ‘Eve de ses décombres’ (Gallimard, 2006), and one of the only films by Mauritians (Harrikrisna and Sharvan Anenden, Ananda Devi’s husband and son) made in Mauritius (a big deal of this was made of a similar story when ‘Grey Matter’ became the first fiction feature made in Rwanda by a Rwandan, in 2011…):

‘Braids on a Bald Head’ is a short film by Nigerian director Ishaya Bako:

Another short, ‘Taharuki’ by Ekwa Msangi-Omari is set in Kenya in the aftermath of its 2008 post-election violence:

‘Bafatá Filme Clube’ is a portrait of cinema operator Canjajá Mané, who’s been on the job for over 50 years in the town of Bafatá (Guinea-Bissau):

Related to the one above is ‘Calypso Rose’, a documentary film about the “diva of Calypso music”. French-Cameroonian filmmaker Pascale Obolo spent four years with Calypso Rose on a journey which took her to Paris, New York, Trinidad and Tobago and “her ancestral home in Africa” [Guinea-Bissau]:

‘Xilunguine, The Promised Land’ is a documentary about a generation of “Tsongas” exchanging their pastoral life for a life in the city (Xilunguine, Maputo):

‘In Search of Oil and Sand’ is a film about a film about a coup d’état shot by members of the Egyptian royal family in 1952 – just weeks before they were swept from power by a real revolution:

And lastly there is the documentary ‘Hinterland’. Synopsis: “In 2002, the young Sudanese asylum seeker Kon Kelei starred in the Dutch feature film Sleeping Rough, about the friendship between a Sudanese refugee and a grouchy war veteran. At that time, the former child soldier had just been refused asylum in the Netherlands. During the shoot and afterward, documentary filmmaker Albert Elings taught Kon how to use a video camera and how to make a video diary of his life … When the situation in Sudan is considered safe enough, Elings follows Kon on his first trip back.” A fragment:

When W magazine went to Johannesburg

Praise be to W magazine for its vanguardism! They have finally and single-handedly put the rest of the world on to how hip, cosmopolitan, and modern the city of Johannesburg truly is! At long last someone has acknowledged the existence of a “multiracial creative class utopia” in downtown Johannesburg. The city is even home to those most crucial indicators of modernity and civilization: hipsters! Who knew?! And best of all, people do not have to be quite as concerned for their personal safety in Johannesburg any longer since crime is not quite as bad as it used to be (even though “one does not feel particularly safe walking” in the city – nonetheless, it’s not really that bad. I promise!).

But wait a minute. The article keeps mentioning a group of young fashionistas calling themselves the Smarteez; a South African indie band known as BLK JKS; and the rap-rave internet phenomenon, Die Antwoord. This is all sounding vaguely familiar. These are the same examples that every trendy Western fashion or pop culture publication has been using for the past several years now, whenever they run special pieces on South Africa.

Not to toot our own horn or anything, but we first talked about the Smarteez back in 2009, in the blog’s earlier incarnation, Leo Africanus. Then, last year, the ‘video magazine,’ Stocktown, published a short documentary on the group, which has been around for something like seven years already. As for BLK JKS, it would be hard to forget how they had American hipster blog The Fader drooling all over them in the run-up to the 2010 World Cup in South Africa. And the same goes for Die Antwoord and the well-known American music site Pitchfork after the (Capetonian!) group’s music videos were featured on the uber-blog, Boing Boing.

Isn’t it time for Western taste-making outlets to ‘discover’ some new South African creative darlings to present as evidence of the country’s (as well as of their own) hipness? Moreover, bands like Die Antwoord and BLK JKS really were only culturally relevant within specific South African niches two years ago, so what makes a publication like W magazine think they would be any more relevant now? They remain South African culture and music for export (much like Spoek Mathambo or Dirty Paraffin). This is not to say that these musicians are making bad music, but I guarantee that if you were to go around Johannesburg asking young people if they liked the BLK JKS, quite a few would wonder who the BLK JKS are.

How about all the great and wildly popular house and kwaito music being produced throughout the country? Musicians like Black Coffee and Zakes Bantwini (members of the South African label, Soulistic Music) are putting out some great ‘deep house’ and slowly beginning to chip away at the global dominance of European and American house acts like Louie Vega and Quentin Harris. Then there are artists like DJ Sbu, Professor, and Shota who are blurring the lines between house and kwaito. In another realm altogether, there are neo-soul and R&B acts like the lovely Zahara, the immensely successful Mi Casa, or the young up-and-coming crooners, The Muffinz. These musicians may not fit the standard hipster mold, but they are certainly hip, cosmopolitan, and creative. It’s a shame that so many fashion and pop culture publications with American readerships are stuck in this groove, writing about the same things for years at a time, whenever their focus is on how cool and stylish South Africans are.

October 9, 2012

Gay Shame

Dear Tanya Harford and Jenny Green,

At 3am in my hotel room last night, jetlagged and sleepless, I was dawdling online and read about the confrontation at Johannesburg Pride between you and a group of black lesbians and feminists who were forcing the march to halt, and demanding a mere 1 minute of silence for all of those who have been raped and killed across South Africa for their sexual orientation or gender expression. I then clicked on the accompanying video and saw one of you revving your car and threatening to drive over the women blocking the way with their banners and their bodies. I saw another of you hurl your white self at one of the black protesters and begin to fight. And as one of the other marchers yelled, ‘go back to the location’, my body turned hot and cold and I started to cry. Not only cry. I sobbed.

I sobbed for the memory of those heady days in the early 90s when we went to the first Gay and Lesbian film festivals. When the likes of Judge Albie Sachs came and spoke at the opening nights and we turned to one another and said, ‘would you ever have imagined?’ When we went to see everything, no matter how bad and experimental, just because it felt so great to see others like us up on the screen.

I sobbed for the memory of the Pride marches I had been on. When it started in downtown Johannesburg and wound through Hillbrow, and the residents of the high rises came down and lined the street as we walked past. Some people shouting encouragement, others yelling abuse. Not because of our race but because of who we slept with. The clusters of mean-faced Christians with their banners yelling ‘God Hates Fags’ and ‘Turn or Burn’. One year we had a piece of the Rainbow Flag from the Pride parade in New York. It was as wide as the road and about 100m long. We held on to it as it billowed in waves, feeling a thrill of connection with that fabled parade across the Atlantic.

I sobbed for the pride we felt when discrimination was outlawed in the Constitution. When we won immigration rights for same-sex partners. When our marriages were legalized.

I sobbed for the women and men I’ve met over the past few years who have still not felt the benefit of all these wonders. Women who cannot bear children because a doctor thought they should be forcibly sterilized simply for being HIV positive. Women and men and trans-people who have shown me the marks and scars on their bodies from fists and knives and ropes and God knows what. The most amazing woman I met early this year, who carries her passport as her most treasured possession – because it means that if she is killed, somebody will know who she is and be able to tell her children what happened to her. All the incredible, truly courageous people across our country for whom you could not spare a minute of silence. Sixty seconds out of 1440 available that day.

Dear Tanya and Jenny, watching what you did on Saturday, my tears surprised me. I’ve seen much worse. Your action was not a crime and a tragedy on the scale of Marikana. It was not even startling and unusual. We’ve always known that racism and bigotry is as rampant in the LGBTI community as it is in the rest of South Africa. What you did was mundane and nasty and mean.

My sobs startled me. You didn’t violate any legacy of mine. I’m no great struggle hero. I’ve been to my share of marches and protests and parades but I haven’t been jailed or beaten or sacrificed terribly much.

Nevertheless, what you did on Saturday, dear Tanya, Jenny and company, robbed me of something sacred. You spat on all of those who have marched before you. You severed any semblance of a connection with a proud legacy. All that pride I’d learned and nurtured and expressed over the years, you took it away. And you replaced it with shame.

Shame on you.

Shame on you.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers