Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 514

November 2, 2012

My favorite things from the last six months

Recently I was asked to pick my “Best Six,” i.e. pick my “favorite (six) things from the last six months” for a regular feature in “Art South Africa” magazine. Here they are. Filmmakers Dylan Valley (also an AIAC contributor) and Khalid Shamis, in the image above, were part of the list. I added the hyperlinks.

Recently I was asked to pick my “Best Six,” i.e. pick my “favorite (six) things from the last six months” for a regular feature in “Art South Africa” magazine. Here they are. Filmmakers Dylan Valley (also an AIAC contributor) and Khalid Shamis, in the image above, were part of the list. I added the hyperlinks.

1. Spoek Mathambo, #APARTHEIDAFTERPARTY #JUNE16, 2012

New South African electrorapper Mathambo released this mixtape to commemorate the 36th anniversary of the famed student uprising against apartheid. Sixty-three tracks — an eclectic mix of South African sounds from the last forty years or so — make up the mixtape. It includes samples and songs from a range of musicians as diverse as Chris MacGregor (of The Blue Notes; Spoek counts him as an influence) to fellow mc Ben Sharpa, nostalgic takes from the eighties (Sipho Mabuse’s “Break dance”) and nineties (TKZee) as well as fellow Jozi hipsters The Brother Moves On (listen to their new EP ‘ETA’ here) and Dirty Paraffin. There’s also ridiculous soundbytes of Julius Malema (“You must treat me exactly like Nelson Mandela”) and Jacob Zuma. Mathambo is a poster boy for a colourblind post-apartheid hipster culture in the West, but the mixtape is proof that he is a more politically astute artist.

2. Mary Beth Meehan, Undocumented, 2012

Meehan, based in Brockton, Massachusetts, photographed the homes of undocumented migrants (from places like Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde and Guatemala) living around New England — people usually blamed for job losses and crime. The photographs show a collection of neat, functional rooms filled with a few personal effects. Meehan decided to photograph the rooms sans occupants, so as not to expose her subjects to adverse attention. As Orlando Reade blogged here at Africa is a Country, “the result of this is a peculiar attention to the dimensions and decoration of rooms and the objects with which they are populated.”

3. PowerMoneySex.org.za From the people who brought you Chimurenga Magazine (remember the all-white cover for the Cape Town issue or the use of a Rotimi Fani-Kayode image for the “Black Gays and Mugabes” cover?), the “speculative newspaper” project, the Chimurenga Chronic (too bad it is not published every Sunday) and the annual music festival the Pan African Space Station comes this Open Society-funded online portal (or blog?) of text, audio, video and photography. It contains a mix of classic texts, cut and paste here and there and fresh writing from young people from across the African Diaspora. It is also proof that despite their success (exhibiting at Documenta 12 and a big Dutch government prize), Chimurenga keep coming up with new, big ideas.

From the people who brought you Chimurenga Magazine (remember the all-white cover for the Cape Town issue or the use of a Rotimi Fani-Kayode image for the “Black Gays and Mugabes” cover?), the “speculative newspaper” project, the Chimurenga Chronic (too bad it is not published every Sunday) and the annual music festival the Pan African Space Station comes this Open Society-funded online portal (or blog?) of text, audio, video and photography. It contains a mix of classic texts, cut and paste here and there and fresh writing from young people from across the African Diaspora. It is also proof that despite their success (exhibiting at Documenta 12 and a big Dutch government prize), Chimurenga keep coming up with new, big ideas.

4. Filmmakers Dylan Valley and Khalid Shamis

Separately they’ve directed critically acclaimed feature documentary films — Valley’s “Afrikaaps” (2010) and Shamis’s “Imam and I” (2011) — but also collaborate regularly. “Afrikaaps“, a film about the creole roots of Afrikaans, is as much also Shamis’s work — he edited it. Capetonian Valley shot his first documentary on hip hop pioneers Prophets of da City (2006) while still a student at the University of Cape Town. “Iman and I” is Shamis making sense of his South African family history: his grandfather is Imam Abdullah Haron, who was murdered by apartheid police in 1969. Their latest collaboration is “Jumu’a: The Gathering” (2012), a short film commissioned by South Africa’s public broadcaster, about a small community of Murabitun Muslims in Muizenberg started by a Scottish convert to Islam. Shamis, who grew up in London, is also working on a film about his father, a Libyan dissident who returned home after the fall of Gaddafi. Shamis destabilizes neat struggle narratives and confronts the duplicitous history of some in the Muslim community in Cape Town.

5. tUnE-yArDs

I first heard the band tUnE-yArDs (that’s the way they write it) in early 2011. They cite reggae crooner Barrington Levy, blues singers Odetta and Woody Guthrie, Fela Kuti, former American first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, film genius Charlie Chaplin and Bertolt Brecht as influences for their brassy mix of rhythmic and melodic chants and loops. I wouldn’t have cared about them, but for lead singer Merrill Garbus. A force of nature (a friend described her as a “musical shaman”). Her voice may comes as a surprise to some. Her style is influenced by a short stay in Kenya and she’s clearly impacted by Björk and Fela Kuti. Garbus, for me at least, also fills the stage — two other contemporary women singers who pull that off are, Brittany Howard of Alabama Shakes and Rita Indiana.

6. Meleko Mokgosi Born in rural Botswana, Mokgosi is a painter who works out of Los Angeles, where his current work, “Pax Kaffraria: Sikhueselo Sembumbulo” (2012), a sixty-foot canvas, part of a series, comprises ten interlocking panels and fills three adjoining gallery walls. I first heard about his work while he was an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Pax Kaffraria is currently on display at the Hammer Gallery. Mokgosi is also a finalist for the Mohn Award, LA’s top prize for young artists. Yael Lipschutz (June 2012): “This allusive visual strategy, in which larger-than-life African priests, soldiers and grandmothers float atop blank zones of negative space, results in a ‘realism’ that is magical, imaginative and fluid. Rather than emulating journalistic set pieces with fixed story frames, Mokgosi’s paintings come to us as detective stories or dreamscapes from a faraway continent.”

Born in rural Botswana, Mokgosi is a painter who works out of Los Angeles, where his current work, “Pax Kaffraria: Sikhueselo Sembumbulo” (2012), a sixty-foot canvas, part of a series, comprises ten interlocking panels and fills three adjoining gallery walls. I first heard about his work while he was an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Pax Kaffraria is currently on display at the Hammer Gallery. Mokgosi is also a finalist for the Mohn Award, LA’s top prize for young artists. Yael Lipschutz (June 2012): “This allusive visual strategy, in which larger-than-life African priests, soldiers and grandmothers float atop blank zones of negative space, results in a ‘realism’ that is magical, imaginative and fluid. Rather than emulating journalistic set pieces with fixed story frames, Mokgosi’s paintings come to us as detective stories or dreamscapes from a faraway continent.”

* This is an edited version of the Art South Africa feature.

November 1, 2012

Sathima Benjamin, jazz and postwar “modern” Africa

[image error]

Recently the life and career of Cape Town-born jazz singer Sathima Bea Benjamin has been the subject of both popular and scholarly attention. In the last two years alone, she’s been the subject of an excellent documentary film (“Sathima’s Windsong” by anthropologist Daniel Yon) and she is one of four jazz musicians profiled in Africa Speaks, America Answers: Modern Jazz in Revolutionary Times, a new book by American historian Robin D. G. Kelley that interrogates the links and influences between American jazz and postwar “modern” Africa. (The other artists featured in the book are Ghanaian drummer Guy Warren and the African-Americans Randy Weston and Ahmed Abdul Malik.) Most significantly, Benjamin has now collaborated with University of Pennsylvania music professor Carol Muller to produce a book-length study of Benjamin’s life and career, Musical Echoes: South African Women Thinking in Jazz.

Muller (also a South African) and Benjamin wanted to ensure that “both the biographical and the geographical coexist[ed]” in the book. The book is structured like a “musical echo”; it uses “a kind of call and response method.” So each chapter consists of a recounting of Sathima’s life (“the call”), followed by Muller’s reflection (“the response”). Muller, though, takes responsibility as the primary author. (The book is the result of 20 years worth of interviews and archival research.)

Benjamin, born in 1936 in Johannesburg and raised in Cape Town, left South Africa in 1963 to forge a music career in Europe and then in the United States alongside her husband, the great jazz pianist Abdullah Ibrahim. Muller credits Benjamin with “discovering” Ibrahim; while in Switzerland, Benjamin introduced Ibrahim (still known as Dollar Brand at the time) to Duke Ellington, who recorded Ibrahim’s trio of South African musicians (minus Benjamin) in Paris, thus launching Ibrahim’s international career.

Ellington also recorded Benjamin, but the recording was never publicly released. For long periods the recordings were feared lost, but were found in 1997 and released to critical acclaim as “Morning in Paris.”

That album, and a 2000 recording “Cape Town Love”, recorded with a group of older Cape Town musicians, serve as bookends to Musical Echoes.

In-between we get frank and rich recollections by Benjamin of her early life—she was at times physically and sexually abused as a child and had a nervous breakdown; and her family did not warm to Ibrahim, whose father was Sotho. We also read about Benjamin’s marriage to the talented and at times dominating Ibrahim; what it was like to be a woman in the jazz world (Benjamin raised two children—her daughter is the rapper Jean Grae and her son is an artist—while running her own label and recording her own music). Her self-imposed exile, the anti-apartheid struggle, and censorship (her most productive period coincided with Apartheid in South Africa) are all covered in stages.

The sections on Benjamin’s childhood and early adulthood double as something of a social history of coloured cultural and social life in Cape Town before the National Party came to power in 1948. The book contains a rich description of talent concerts, dance bands, jazz clubs, and the impact of radio, records and cinema on Benjamin’s imagination and musical education.

While Benjamin was classified as coloured, she rejected that label; instead emphasizing her cosmopolitanism, including her family roots in St Helena, a small island in the South Atlantic as well her connection to New York City, her home from 1977.

While in exile, Benjamin’s racial identity (Muller describes Benjamin at one point as “a women of ambiguous racial marking”) and the fact that she sings in English, complicated her position. The exiled ANC would often exclude her from singing at their events because she was “not African enough” and American music executives and promoters preferred the equally talented Miriam Makeba singing in “exotic” African languages.

The book (part of a Duke book series on “Refiguring American Music”) contributes to a growing literature on the intersection of US-South African cultural politics and history (see, for example the work of Rob Nixon, Robert Vinson, and younger scholars like Tyler Fleming). Musical Echoes also contains sections on South African musicians and Cold War politics. Muller reveals Benjamin and Ibrahim’s entanglements with the CIA-sponsored Transcription Center in London—“the most significant site for South African musicians, artists and writers”—throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. Sathima was “not enthusiastic” about revealing these connections.

Muller has preoccupations similar to Robin Kelley’s: both aim to complicate jazz history by showing how Africans reshaped American jazz in the twentieth century. For Muller, Benjamin’s transnational travels and influences “constitute a worldwide, comparative, and more equitable representation of jazz historiography” from the “margins of jazz history. The aim is not to read jazz cultures—in the US and elsewhere—in parallel, but “to put jazz cultures in dialogue with each other.” Muller describes Benjamin as “a voice that is incessantly in exile,” negotiating a complicated relationship with New York City, where she lived and performed for much of her professional life, and Cape Town, where she started her career and where she recently returned to live.

* This is an edited version of a review first published in The International Journal of African Historical Studies.

Sathima Benjamin, American jazz and postwar “modern” Africa

[image error]

Recently the life and career of Cape Town-born jazz singer Sathima Bea Benjamin has been the subject of both popular and scholarly attention. In the last two years alone, she’s been the subject of an excellent documentary film (“Sathima’s Windsong” by anthropologist Daniel Yon) and she is one of four jazz musicians profiled in Africa Speaks, America Answers: Modern Jazz in Revolutionary Times, a new book by American historian Robin D. G. Kelley that interrogates the links and influences between American jazz and postwar “modern” Africa. (The other artists featured in the book are Ghanaian drummer Guy Warren and the African-Americans Randy Weston and Ahmed Abdul Malik.) Most significantly, Benjamin has now collaborated with University of Pennsylvania music professor Carol Muller to produce a book-length study of Benjamin’s life and career, Musical Echoes: South African Women Thinking in Jazz.

Muller (also a South African) and Benjamin wanted to ensure that “both the biographical and the geographical coexist[ed]” in the book. The book is structured like a “musical echo”; it uses “a kind of call and response method.” So each chapter consists of a recounting of Sathima’s life (“the call”), followed by Muller’s reflection (“the response”). Muller, though, takes responsibility as the primary author. (The book is the result of 20 years worth of interviews and archival research.)

Benjamin, born in 1936 in Johannesburg and raised in Cape Town, left South Africa in 1963 to forge a music career in Europe and then in the United States alongside her husband, the great jazz pianist Abdullah Ibrahim. Muller credits Benjamin with “discovering” Ibrahim; while in Switzerland, Benjamin introduced Ibrahim (still known as Dollar Brand at the time) to Duke Ellington, who recorded Ibrahim’s trio of South African musicians (minus Benjamin) in Paris, thus launching Ibrahim’s international career.

Ellington also recorded Benjamin, but the recording was never publicly released. For long periods the recordings were feared lost, but were found in 1997 and released to critical acclaim as “Morning in Paris.”

That album, and a 2000 recording “Cape Town Love”, recorded with a group of older Cape Town musicians, serve as bookends to Musical Echoes.

In-between we get frank and rich recollections by Benjamin of her early life—she was at times physically and sexually abused as a child and had a nervous breakdown; and her family did not warm to Ibrahim, whose father was Sotho. We also read about Benjamin’s marriage to the talented and at times dominating Ibrahim; what it was like to be a woman in the jazz world (Benjamin raised two children—her daughter is the rapper Jean Grae and her son is an artist—while running her own label and recording her own music). Her self-imposed exile, the anti-apartheid struggle, and censorship (her most productive period coincided with Apartheid in South Africa) are all covered in stages.

The sections on Benjamin’s childhood and early adulthood double as something of a social history of coloured cultural and social life in Cape Town before the National Party came to power in 1948. The book contains a rich description of talent concerts, dance bands, jazz clubs, and the impact of radio, records and cinema on Benjamin’s imagination and musical education.

While Benjamin was classified as coloured, she rejected that label; instead emphasizing her cosmopolitanism, including her family roots in St Helena, a small island in the South Atlantic as well her connection to New York City, her home from 1977.

While in exile, Benjamin’s racial identity (Muller describes Benjamin at one point as “a women of ambiguous racial marking”) and the fact that she sings in English, complicated her position. The exiled ANC would often exclude her from singing at their events because she was “not African enough” and American music executives and promoters preferred the equally talented Miriam Makeba singing in “exotic” African languages.

The book (part of a Duke book series on “Refiguring American Music”) contributes to a growing literature on the intersection of US-South African cultural politics and history (see, for example the work of Rob Nixon, Robert Vinson, and younger scholars like Tyler Fleming). Musical Echoes also contains sections on South African musicians and Cold War politics. Muller reveals Benjamin and Ibrahim’s entanglements with the CIA-sponsored Transition Center in London—“the most significant site for South African musicians, artists and writers”—throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. Sathima was “not enthusiastic” about revealing these connections.

Muller has preoccupations similar to Robin Kelley’s: both aim to complicate jazz history by showing how Africans reshaped American jazz in the twentieth century. For Muller, Benjamin’s transnational travels and influences “constitute a worldwide, comparative, and more equitable representation of jazz historiography” from the “margins of jazz history. The aim is not to read jazz cultures—in the US and elsewhere—in parallel, but “to put jazz cultures in dialogue with each other.” Muller describes Benjamin as “a voice that is incessantly in exile,” negotiating a complicated relationship with New York City, where she lived and performed for much of her professional life, and Cape Town, where she started her career and where she recently returned to live.

* This is an edited version of a review first published in The International Journal of African Historical Studies.

Film Africa (6): ‘Tey’

In the beginning, we are addressed in quote. “This is a place where Death sometimes still warns of its passing. How? No one could answer exactly. It happens the day before, like a certitude that descends upon our bodies and minds…” Against a brooding shot of the breathing sea, cloaked in near darkness — our original womb — a baritone voice speaks, “A tale”. In unison a group responds, “Tell us”. The grave voice continues, “Once upon a time”, the group complies, “It really happened.” “Were you there?”, he asks. “It’s up to you to tell.” The sea collapses to a vacant black screen before being illuminated with a fluid, blood red nebulous, as if you are sitting in a red tent aglow from outside light. Alain Gomis has us and his protagonist born into his latest film: ‘Tey’, ‘Aujourd’hui’, today.

In the beginning, we are addressed in quote. “This is a place where Death sometimes still warns of its passing. How? No one could answer exactly. It happens the day before, like a certitude that descends upon our bodies and minds…” Against a brooding shot of the breathing sea, cloaked in near darkness — our original womb — a baritone voice speaks, “A tale”. In unison a group responds, “Tell us”. The grave voice continues, “Once upon a time”, the group complies, “It really happened.” “Were you there?”, he asks. “It’s up to you to tell.” The sea collapses to a vacant black screen before being illuminated with a fluid, blood red nebulous, as if you are sitting in a red tent aglow from outside light. Alain Gomis has us and his protagonist born into his latest film: ‘Tey’, ‘Aujourd’hui’, today.

Satché (Saul Williams) awakes in his mother’s house. Lying on a bed, he touches himself tenderly on his stomach, he is here, but as he soon discovers, when he closes his eyes at night, he will leave with death. Gomis describes his film succinctly as ‘the kind of tale that takes place in an imaginary society in which death comes looking for someone’. Satché leaves his room, generous with memories in objects and photographs, to a mourning party reception. His mother clings onto him as his father releases her midwife-like clasp, “Be brave, be brave. Let him go.”

Having filmed in luscious colours, Gomis elevates naturalism through his visual diction to a kind of serene poeticism, which feeds the films impressionistic, magical realism. Stretching time in each scene, he allows the content to linger, asking the viewer to consume the film instinctively, emotionally and in fragments. Gomis allows the narrative to suspend itself in a collection of moments, a gentle cradling of the film’s unique temporality, as we explore Satché’s eulogy.

Satché meanders through an anonymous city in Senegal to what is most meaningful to him: his community, friends, an old but now dispassionate lover, his uncle and finally to his wife and children. Having returned from studying in the U.S., Satché perceives with childlike, wide eyes his surroundings as both familiar and unfamiliar. But the protagonist’s impending death catalyses his reintroduction to his ‘home’, sharpening his sight. Satché embarks on a self-reflexive journey to resolve his feelings of incongruity where “Time does not seem the same anymore, and suddenly he starts seeing the world with the eyes of a stranger — someone who is about to leave.” Carrying himself like a flâneur, Satché vibrates between: lightness and weight, dread and dream, burden and levitation. Confessing his emotions deftly upon his face, accentuated by Gomis’s economic use of dialogue, it is through Satché’s journey that Gomis dissolves these conceptual poles — of life and death — to a tender haze. Blending the codes and symbols of lightness and weight to produce a soulful warmth as one.

The narrative ebbs when Satché purposely visits his Uncle Thiemo (Jean Mendy) to ask if he will wash him for burial. While Satché lies on the ground motionless, his uncle demonstrates how he will prepare him for his soul’s departure. This reverential moment, both chilling and cleansing, allows Satché to accept his fate in entirety. After the demonstration, he stands and walks to collect himself; in portrait, we see a single tear left to run down his face. Expressing an Amor Fati, ‘love of one’s fate’, that within death, life is affirmed.

Satché stands stagnant on a street while Gomis temporarily surrenders his dreamlike colours for reality. A series of short vignetted scenes follow that feel like portraits in Satché’s mind as he gazes into his ‘home’. Three children dance in unison on a crowded road, a group of men argue and fight, a petrol bomb is thrown, a women shouts through the screen “You want to know the truth. The king’s sons are princes? The prince’s sons are thugs. There’s a gas and coal shortage. Even the teachers are on strike. What will become of our children tomorrow? We are fed up! Especially the women.” People bustle in a mass protest. Gomis reapplies his fantastical colour palette as Satché walks languidly, looking upon the disbanding protest. His innocence has dispersed from his face as he is once again joined with Sélé (Djolof Mbengue) who has lovingly shepherded him throughout the film.

The practical silence and enduring presence of Sélé throughout the film, is suggestive of him as author or mind of Satché, while Satché navigates his perception of ‘home’ through experience. Satché’s endeavour to re-establish himself within his ‘home’ during his last day on earth imbues the narrative arc with a meditation on identity, alienation and migration. So when his eyes droop shut while lying with his wife in bed for the last time, in death, through art, he is unified in mind and body. Dissolving the duality as his true identity and self are reconciled, but as his uncle asserted “No one ever finishes anything, we just stop.”

* Africa is a Country is a media partner of Film Africa, the UK’s largest annual festival of African cinema and culture (starting in November 2012 for 10 days showing 70 African films) in London. Tey screens twice during the festival:

Fri, 9 November 2012, 6:30pm, The Ritzy (Followed by a Q&A with director Alain Gomis)

Sat, 10 November 2012, 8:45pm, Hackney Picturehouse.

10 films to watch out for, N°9

In no particular order, here are another 10 films — still in production, recently completed or already making the rounds — we hope to see one day. All of them documentary films this week. First up, Electrical Rites in Guinea-Conakry, Julien Raout and Florian Draussin’s music documentary on the omnipresence, the appropriation and the different roles of the electric guitar in Guinea’s musical landscape. Trailer above. Next, Le Chanteur de l’Ombre (“Singer from the shadow”) is Yann Lucas’s portrait of maloya singer Simon ‘Dada’ Lagarrigue, “pillar of the culture of Réunion” (film pitch), and the role Dada played in the political and union fights in the French département d’outre-mer during the seventies and eighties:

In Revolution under 5′ Rhida Tlili tails a group of Tunisian street artists (Ahl el Kahf) in the wake of the ousting of Ben Ali:

Cinéma Inch’Allah! is a film about four Belgian-Moroccan friends who grew up making movies; the documentary follows the production process of their latest film. Promising trailer in French:

The Last Hijack is a film about two Somali cousins — “both a feature-length documentary and an online transmedia experience, which offer the viewer a unique and original way to explore the story of Somali piracy from different perspectives,” according to the production’s very serious notes:

La vie n’est pas immobile (“Life isn’t immobile”) is Senegalese director Alassane Diago’s portrait of Houleye Ba, leader of a group of “indignées” women who stand up against their men’s decision over what will happen to their land. No English subtitles yet:

Arian Astrid Atodji put to film the villagers of Koundi’s (East Province, Cameroon) decision to organise a union and to create a cocoa plantation to be able to depend on themselves, very much aware of the riches they sit on. Koundi, Le Jeudi National (“Koundi, National Thursday” — a reference to the monthly day on which the villagers all work on the development of the plantation) is a film from 2011 but only recently surfaced at international film festivals. As yet, no English subtitles either:

In Letters from Angola Dulce Fernandez delves into the lives of six Cubans (men and women) and their relation with, and participation in, the Angolan War for Independence:

Documented over eight years, Afrikaner Girl is Annalet Steenkamp’s first feature length documentary. It’s a portrait of a South African family (her family) — four generations of Afrikaners in rural South Africa:

And finally, also set in rural South Africa (Eastern Cape), is Tim Wege’s King Naki and the Thundering Hooves. Here’s the official trailer, but watch this 12 minute fragment:

Next week: more fiction.

October 30, 2012

Only decent white people know how to insult

The most talked about film in the Netherlands now is the comedy Alleen Maar Nette Mensen (“Only Decent People”), which, to be blunt, may shape Dutch views of its black citizens, and Afro-Surinamese in particular, in very negative ways from which we may not recover for a while. The film is already a smash hit. It is based on a controversial bestseller by Dutch author Robert Vuijsje that in 2009 also caused a heated debate about the portrayal of Surinamese as oversexed and simplistic–in fact, Vuijsje has received death threats because of the film. But now, with real life people acting out the stereotypes, it becomes just more appalling.

The most talked about film in the Netherlands now is the comedy Alleen Maar Nette Mensen (“Only Decent People”), which, to be blunt, may shape Dutch views of its black citizens, and Afro-Surinamese in particular, in very negative ways from which we may not recover for a while. The film is already a smash hit. It is based on a controversial bestseller by Dutch author Robert Vuijsje that in 2009 also caused a heated debate about the portrayal of Surinamese as oversexed and simplistic–in fact, Vuijsje has received death threats because of the film. But now, with real life people acting out the stereotypes, it becomes just more appalling.

As this film probably won’t be shown outside of the Dutch speaking world, the trailer may be the only way to get an introduction to what the film is about and moreover, why it’s so controversial:

It’s useful to set the context first. The blog Afro-Europe (which focuses on cultural politics and media portrayals of people of African descent in Western Europe) has posted a detailed English translation of the trailer. But here’s a quick summary of the trailer: the protagonist David Samuels is a “nice Jewish guy” who is bored with his vanilla life. He hates his girlfriend and his “overbearing” mother. He develops “a thing” for black women. He tells two black friends: “The darker she is, the closer she is to nature.” He falls for Rowanda (“Is that a Dutch name?”, asks his father). She is 23 and has 2 kids. When parents and girlfriend finally meet, David informs his parents: “We eat on the couch.” Black men tease him: “You are going to tell me that Rowanda is your only chick.” Soon David turns into “a gingerbread”: a white man who “hangs around with black people too much” and takes on “all the bad habits” presumably associated with black men. The trailer ends with an angry Rowena screaming at David: “Fuck you with your posh neighborhood. Only decent people!”

Anyway, I went to go see it. If you find the trailer insulting and tasteless, the film is much worse.

Because David has no “swag,” nor any black friends, he phones the only black person he knows from back in high school, hoping he can hook him up with “a black negro woman,” and more precisely a “ghetto queen.” It soon becomes clear what is meant by that descriptor: a black woman who wears hot pants three sizes too small, spends large sums of money on her hair (extensions) and nails and, most prominently, has a big butt.

Of course his friend takes him to “the field” where he will collect his “ghetto queen.” Rowanda lives in the Bijlmer, a real-life, largely immigrant and Dutch Surinamese neighborhood in Amsterdam of concrete high-rise buildings developed in the late 1960s. The Bijlmer is situated south-east of the city centre and is sometimes called “Little Paramaribo,” an endearing reference to the capital of Suriname.

Every conceivable cliché and racist prejudice about Surinamese people and the Bijlmer is put into action.

For those not familiar with Dutch colonial history, Suriname is a small country in South America between Guyana and French Guyana to the east and west respectively, and Brazil to the south. Suriname gained its independence in 1975. Surinamese have always migrated to the Netherlands, but there was a large influx, especially to Amsterdam, following a 1980 coup by Desi Bouterse (the current democratically elected president).

Suriname, like other countries in the Caribbean, has a mixed population with no real racial or ethnic majority. It’s divided between Creoles or Afro-Surinamese (black people, descendants of slaves) and South Asians (brought to Suriname as contract workers after the abolishment of slavery). But for many Dutch people, Suriname might as well be an island of just black people.

Because of a number of socio-economic problems, which are not endemic to the Netherlands but were seen in many urban areas with a large concentration of third world migrants, the Bijlmer soon became the Netherlands’ “ghetto.” Although ghetto is a very strong word with devastating consequences in recent European history and despite the neighborhood being subject to gentrification more recently, it is still seen as a “no-go area” by those living outside it.

Rowanda is depicted as the “average” Bijlmer resident. She doesn’t seem to have a job. Her children are from two different men who in turn cheated on her with dozens of other women. Because of her seemingly “traumatic” experience with men, Rowanda is already a “mad black woman.” Don’t mess with her, or she’ll set you on fire or cut off your penis. Apart from Rowanda’s mother, all her friends — in fact all black women — in the film are portrayed as “ghetto fabulous” women with big booties and appear not to have any problem sleeping with whoever “talks the talk.” None of them seem to have any agency over their own body. The sex seems coercive as the men, in exchange for sex, buy the women clothes, mobile phones or hair extensions.

Rowanda is depicted as the “average” Bijlmer resident. She doesn’t seem to have a job. Her children are from two different men who in turn cheated on her with dozens of other women. Because of her seemingly “traumatic” experience with men, Rowanda is already a “mad black woman.” Don’t mess with her, or she’ll set you on fire or cut off your penis. Apart from Rowanda’s mother, all her friends — in fact all black women — in the film are portrayed as “ghetto fabulous” women with big booties and appear not to have any problem sleeping with whoever “talks the talk.” None of them seem to have any agency over their own body. The sex seems coercive as the men, in exchange for sex, buy the women clothes, mobile phones or hair extensions.

The men on the other hand only live for sex and with the exception of their own mother are portrayed to have no respect for women as they cheat and lie all the time while glorifying their behaviour.

Nearly all black people in the film talk with an accent, all are loud and no one appears to have any intellect.

Much can be said about the film and the portrayal of stereotypes. But what has struck me the most has been the debate about whether the film is racist or not.

The film has come in for some fierce criticism, mainly from black critics in the Netherlands, whether a few in the mainstream, on blogs or other social media (on Facebook and Twitter); mostly in Dutch. Here, for example, you can read the criticisms of the artist Quincy Gario who questions why people who have some knowledge of the Bijlmer did not make the film. He also questions why public money (which partly subsidized the film) was used to propel century-old racist images into the world.

The film’s producers and its director responded to critics by saying it is all entertainment; that the film should be read as satire. And what with the portrayal of black women? The film is an ode to them, according to the actor Géza Weis, who plays David. So, in 2012, portraying black women simply as brainless whores seems to constitute homage.

Author Vuijsje’s wife, who is black, approves of the book and film. Supporters of the film cite this as further evidence that the criticism is “over the top.”

The most striking development since the film premiered, is ‘left-wing’ Dutch media going out of their way to defend the film and argue it is not racist. Nausicaa Marbe, a writer and prominent columnist for De Volkskrant, argued that the film is not a freak show. In the same article, however, Marbe argued that the Bijlmer is “a dangerous neighborhood.” The Dutch public broadcaster’s breakfast news called the controversy around the film “a fuss.” And Dutch academics have also weighed in. Sociologist Jan Dirk de Jong argues that critics don’t understand the narrative since, according to him, it is not about ethnicity, but about social and cultural class. De Jong failed to acknowledge that these classes have been historically constructed in the Netherlands along racial lines and that they continue to exist today.

On top of that, it turns out that the only way for actress Imanuelle Grives got to play Rowanda, was by gaining 15 kilograms, or she wouldn’t have looked “authentic” enough.

Defenders of the film also the deny charge that the narrative could in any way be racist, by putting forward an argument about High Literature: the novel won the esteemed Golden Owl literature prize (for Dutch language Literature) in 2009 and the Inktaap Literature Prize, a prize awarded by high school pupils.

The Dutch, obviously, are very sensitive to accusations of racism and discrimination. The country prides itself on being one of the most liberal and multicultural societies in the West. Reality suggests otherwise. The use of the word neger (“negro”) in the Dutch language serves as a perfect example. For instance, in the film, David is said to be craving for a “black negro women.” The word “neger” is commonplace in everyday usage to refer to a black person. In 2006 — following years of complaints — the Dutch version of the chocolate-coated marshmallow called negerzoen (“negro kiss”) was changed to just “Kiss.” Not because it was deemed racist or racially sensitive. No, only because it was regarded as “politically incorrect”. Today, however, in every day use people still refer to the chocolate as “Negerzoen”.

The Dutch, obviously, are very sensitive to accusations of racism and discrimination. The country prides itself on being one of the most liberal and multicultural societies in the West. Reality suggests otherwise. The use of the word neger (“negro”) in the Dutch language serves as a perfect example. For instance, in the film, David is said to be craving for a “black negro women.” The word “neger” is commonplace in everyday usage to refer to a black person. In 2006 — following years of complaints — the Dutch version of the chocolate-coated marshmallow called negerzoen (“negro kiss”) was changed to just “Kiss.” Not because it was deemed racist or racially sensitive. No, only because it was regarded as “politically incorrect”. Today, however, in every day use people still refer to the chocolate as “Negerzoen”.

Then in December 2011, Dutch fashion magazine Jackie took it a step further. The editor decided to give its readers fashion advice: they could dress like a “Nigga Bitch.” The magazine associated the “style” with pop singer Rihanna. When Rihanna, in colourful language, objected on Twitter, the editor was forced to resign. Many black Dutch people believe the editor would have kept her job, if the controversy hadn’t been picked up outside the Netherlands. In fact, as is the case now, critics were labelled as too sensitive and taking the matter too seriously — when the editor was first confronted about the racist slur, she responded that it was just a “bad joke.”

It is not so surprising then that Alleen Maar Nette Mensen could be produced and turn into a hit in a country where it’s regarded as an offense to label something or someone’s remarks racist. It’s also a country where people who are of ‘non-western’ decent are labeled allochtoon (“allochthonous”), and this not only by the white (autochthon) society, but also by law.

And of course the most problematic example of the Dutch’s engagement with black people remains the annual controversy around ‘Zwarte Piet’ (or ‘Black Pete’) which we blogged about before.

It seems to be part of the Dutch discourse to deny any form of critique of “race relations” or cultural politics in the Netherlands, and there seems to be a lack of understanding that cultural expressions and words such as “neger” which are perceived as “normal” and are used in everyday life can still be hurtful to people.

One does not have to be a racist to say or do something racist.

Attempts in Dutch media to discuss how some members of the Afro-Surinamese community feel misrepresented by Alleen Maar Nette Mensen, led to Afro-Surinamese opinions being muted by irrelevant arguments that not only black people are mocked in the film, but also Jews, Moroccans and Dutch people.

It might me true that jokes are indeed made about other communities in the film, but these are merely comments made by the characters. Jewish people are the one other group subjected to stereotypes; but they — David’s parents, his ex-girlfriend and his relatives — are represented, at worst, as quirky. It is stereotypes of black people that are constantly confirmed – not only in the interaction with other black people, but also when juxtaposed to white people. (David’s ex-girlfriend is appalled by the “dirty things” he has been doing in the Bijlmer. Instead of challenging her views, the idea of dirty sex of black bodies is reinforced by sex scenes of gangbangs in a random apartment and the camera lingering over black women’s bodies).

The final straw is the use of a remixed version of the Surinamese anthem as the movie score that makes the reproduction of historical stereotypes of Afro-Surinamese people and people living the Bijlmer complete.

The fact that the film is controversial has made it a huge commercial success, and ironically not just in the Netherlands, but also in Suriname, where in the first week after it premiered, it was .

This, no doubt, will serve as more fodder and evidence for the supporters of the film that critics are too sensitive about the narrative. Unlike to what one might expect, a large part of the Afro-Surinamese community doesn’t feel the film misrepresents them. Other members, on the Surinamese forum Mamjo.com, have called for a boycott. But one commenter, calling herself Rowanda, has written: “If white people want to believe all Surinamese are like that, then that is their problem.”

Debating Afrocolombianidad

Gold miners in Tadó (Chocó, Colombia) are predominantly Afro-Colombians [Photo © Jan Sochor]

Most people outside Colombia know about the country’s African population through the music of groups like Latin Grammy winners Choquibtown, with their references (see here and here) to Chocó, a Colombian state populated by a majority of African descendants. In their song El Bombo, Choquibtown sing: “Encima África viva — ¡Mía! Esta es mi herencia llena de alegría” (And Africa is alive — It’s mine! This is my heritage full of happiness).Despite Choquibtown’s efforts to create awareness about other aspects of Afro-Colombian life, people in Colombia and around the world continue to associate Afro-Colombians largely with dance or music, “but they refuse to actually show any kind of real solidarity with African Colombians,” according to Claudia Mosquera, professor of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Mosquera was one of the guests of a special edition on current Afro Colombian issues of Punto Crítico, a show aired by the university’s channel Prisma TV, which you can watch online here (in Spanish).

A further concern brought up in the program is that the local population does not want to be related to Afro-Colombians’ historic experience and that Afro-Colombians, in turn, in many cases, don’t want to either.

Gold mining makes one of very few work opportunities in the inhospitable jungle region

on the pacific coast of Colombia. [Photo © Jan Sochor]

Meanwhile Mosquera spelled out the many ways of Afro-Colombian identity: the acknowledgement of an African history of tragedy and resistance, without considering themselves as victims, but instead revisiting their role in the construction of the nation. For others, instead, it is a way to escape from that historical moment and just recognize themselves through cultural expressions and kinship. It can be almost like a “fashion trend”, she says. Finally, there is a group that might consider itself Afro-descendent in those situations in which they need to apply to certain benefits established by the multi-ethnic and multi-cultural state.

Contrary to popular belief, the largest population of African descendants is located in Colombian cities. However in urban areas the acceptance of an “Afro identity” is lower than in rural areas. That said, the countryside is not a safe haven for cultural heritage as Afro-Colombian families located in areas such as the South Pacific and the Coast of the state of Nariño remain to be forcibly uprooted as a consequence of the current armed conflict. Furthermore, the conflict risks the lives of those who carry knowledge of black culture. Both in urban and rural areas, this population lives in poor conditions, but many do not believe they are living any kind of hardship, given that kinship networks allow them to think poverty is something they can overcome. “Poverty is not politically processed by those who live it nor by the organizations working for their well-being,” according to Mosquera.

In the midst of this confusing process of recognition and identity politics of and by Afro-Colombians, at the local level a crucial step has been the passing of many laws for their protection. Still “legal treatment is homogeneous to other vulnerable populations, and does not take into account Afro-Colombian social dynamics and cultural specifics,” said activist Martinez.

The daily earnings of gold miners do not reach over a couple of dollars but every barequero is convinced that thousands of dollars can be made here. [Photo © Jan Sochor]

Lately, music has not been the only vehicle to create awareness and discussion; TV and films have made efforts towards this goal as well. Besides Punto Crítico, the film La Playa D.C. (trailer here), for example, screened locally and internationally, exploring emerging black identities marked by dilemmas related to the African ancestry of the countryside, which is continuously being transformed as thousands of African Colombians keep moving to cities such as Bogotá.Watch: Afrocolombianidad.

* Photographs by (and with kind permission of) Jan Sochor from his series on Women Gold Miners in Chocó department, western Colombia (October 2004).

Film Africa (5): ‘The Assassin’s Practice’

Somewhere in the opening shot of The Assassin’s Practice there is a woman crying alone in bed, tangled in a blue room. If the sound of her racking sobs is enough to turn your stomach, you won’t be able to handle all of the sudden hysterical plot twists or the unpredictable side stories that fuel Andrew Okoko’s latest thriller. The Assassin’s Practice runs the overwrought, low-budget excess of Nollywood off the rails.

It starts out innocently enough; a respected stockbroker, secretly failed gambler, and desperate family man puts in motion an elaborate plot to kill himself, and make his own death look like a violent crime, so that his second wife and bratty daughter can keep up their lavish living on his life insurance policy.

Then you begin to notice that Okoko has tampered with the tempo of melodrama. Skeletons and confessions come out faster than they can develop intrigue. Clever dialogue winks at us, and the talented Kate Henshaw takes a backseat to static shots to announce, “I hate clichés.”

Consider this a response to Steven Soderbergh’s masterful Bubble. Okoko’s Assassin movie cuts prepared emotional responses off short; asks the audience hard questions about artifice, fidelity, and the anxieties that are true-to-life; and keeps one eye on its own charm.

Although its wit can seem a bit smug, the film is strengthened by its honest discussion of the uncertain loyalties of pop culture. Our sense of place “in Largos” is exposed as a series of clichéd images. A mysteriously glamorous London beckons, and the daughter announces she won’t go on safari with her father’s second wife because, “there’s no telling you’ll do with my passport.”

* Africa is a Country is a media partner of Film Africa, the UK’s largest annual festival of African cinema and culture (starting in November 2012 for 10 days showing 70 African films) in London. The Assassin’s Practice screens Sun, 4 November 2012, 8:45pm Hackney Picturehouse.

October 29, 2012

Film Africa (4): ‘Veejays in Dar es Salaam’

My first thought was wow; some anthropologists went to Tanzania to make a documentary about the politics of translation and made something a lot more fun. This is the inside story of Lufufu and DJ Mark, the best of the best of the charismatic men who have broken into the entertainment industry dubbing international blockbusters and narrating them for live audiences in small theaters on the edge of East Africa’s cosmopolitan centers.

Portraits of the VJs as established masters and scrappy upstarts respectively are stitched together from a series of interviews with veteran promoters, fans, and their rivals. The biggest question — when are you satisfied with your work? and, what would you rather be doing — are directed at the VJs themselves. They also give studio tours and interviews, talking warmly about the kind of details and explanations they add to help their audiences contextualize the films, for example that Titanic scene of Kate Winslet dancing down in steerage. (And make us think about the explanations we’ve seen authorized before.)

Veejays comes across as an earnest attempt to learn about the ways people are remixing dominant culture industries to make their own. Cameras follow interviewees’ instructions to see tools of the trade, personal libraries, and demos. Quiet cuts and tight frames assure our attention. But it is also an ambitious project; made for the big screen. Long shots of the audience at live performances inside small, sandy theaters in Dar es Salaam face out into another audience in an impossible act of seeing.

Like classic anthropologists, the filmmakers Carvajal and Gross keep their international film crew out of their shots. Their panoramic views are what make this demented mirror work but also leaves us to wonder who is calling the shots during the shoots. (Who is being told to stand where?)

Happily, the organizers at Film Africa have organized a guest VJ performance, promising to push the vanguard of global pop culture consumption. You should be there, especially if you are already in London.

* Africa is a Country is a media partner of Film Africa, the UK’s largest annual festival of African cinema and culture (starting in November 2012 for 10 days showing 70 African films) in London. Veejays in Dar es Salaam screens Sun, 4 November 2012, 12:00pm Rich Mix

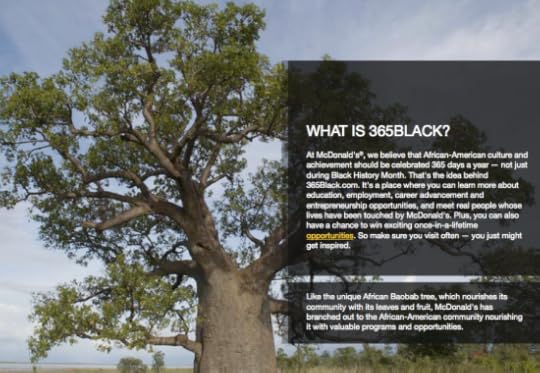

McDonald’s Baobab Tree

These days, it’s not uncommon to see Western fast food chains alongside local favorites in the post-colony. Lagos, for example, has its Nigerian fast food chains (Mr. Biggs, Chicken Republic, etcetera) but also a brand-new, shiny KFC in the upscale Ikoyi neighborhood, a symbol to many of the city’s modernization and integration into the world economy. This kind of “culinary imperialism” has been discussed before, but less discussed has been the inverse — the use of black and African pride by Western fast food chains to appeal to African-Americans.

Enter McDonald’s new website, 365Black, whose slogan reads “Deeply rooted in the community®!” How deeply? As deeply as “the unique African Baobab tree, which nourishes its community with its leaves and fruit,” just as “McDonald’s has branched out to the African-American community, nourishing it with valuable programs and opportunities.”

The website features pictures of smiling young African-Americans, one even in a cap in gown — if you eat at McDonald’s, it suggests, you’ll be as beautiful and successful as these beautiful people! In its “Opportunities” section, it touts the Ronald McDonald House’s college scholarship program as evidence of its deep roots, but it also touts McDonald’s’ “diverse employment.” Never mind that these diverse employees are paid, on average, about $7.60 an hour, perpetuating cycles of poverty or at least preventing the kind of upward mobility touted on 365Black for many of its employees.

Of course, not all of McDonald’s employees are black, and neither are all of its customers. But the chain’s role in promoting fatty, unhealthy foods in areas with low purchasing power, many of which are predominantly black, is so obvious it need not be addressed. What ought to be addressed, briefly, is the defense of McDonald’s and other fast food chains, which claims that fast food is the cheapest way for the poor to feed themselves. Not true. So even from a “we provide calories” standpoint, McDonald’s has no legitimate claim to being vital for the community, African-American or otherwise.

Aside from issues of health, hegemony, and markets, what we have here is McDonald’s, a Western behemoth pushing a product that could not be even remotely considered African, using an African symbol to appeal to a population of African origin, in order to make itself look like something it isn’t. And it’s a shame that this tactic hasn’t been attacked more widely.

* Justin Scott is a graduate student in African studies at Yale, focusing on access to energy, information, and social networks in Nigeria.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers