Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 512

November 19, 2012

French-Algerian sculptor Rachid Khimoune exhibits in New York City

Rachid Khimoune grew up in a small mining town in Northern France where his Algerian parents had settled. It was there that he saw first hand the end of industrialisation: his father lost his job at the local mine and the family moved to the suburbs of Paris. The waves of urban immigration to the cities is a phenomenon important to Rachid’s work — his word for it is ‘transhumance’, or the seasonal migration of grazing flocks, their exodus to the city, a new forms of verticality — and he is particularly attentive to its effects in the capital cities of the world.

The Algerian war broke out before the move to Paris, and Rachid remembers how his family — who “felt French, completely integrated” — were treated by the other villagers. He remembers hearing about the hundreds of Algerians driven into the Seine by the French police in 1961. He speaks of a certain look they received, and connects this to his interest in the manhole cover — called, in French, ‘un regard’. This bizarre confluence of meaning, between the intangibility of the glance and the object wrought in iron, expresses a contradiction central to Rachid’s work. He is, he says, a maker of poetic images.

His most extensive work to date is Children of the World, a project long in development which culminated with an installment at the Bercy Park, Paris in 2001. To celebrate the transition into the twenty-first century, Rachid took from twenty-one different capital cities a ‘flesh of the street’ (he retranslates it ‘peau de la rue’). Moulding objects and collecting ephemera from various streets, Rachid put together twenty-one figures of ‘children’, ambassadors of cities entering a new century.

A more recent public project involved the installation of a thousand bronze tortoises on Omaha Beach in 2011, to commemorate the landings of Allied troops [top image]. There are several tortoises, in plastic and bronze, on the floor of the Friedman & Vallois gallery in New York — and I’m reminded of the tortoise in Huysmans’s novel A Rebours (Against Nature) whose shell is encrusted with jewels. Rachid’s tortoises, however, are cast in bronze and moulded by the shape of the helmets of the soldiers who fought in the D-Day campaign.

Tortoises, Rachid says, are used in North Africa to clean the house, at the same time as warding off “bad luck and evil spirits”. The tortoise is “a symbol of wisdom” and a metaphor for the longevity of war. The works reminds me of Jacob Epstein’s Rock Drill or Picasso’s work in bronze, and Rachid talks of its relation to art of the early twentieth-century: “they said never again, but every decade there are more wars.” In Mozambique Gonçalo Mabunda has also, recently, been making tribal masks from weapons.

Rachid’s newer works, also on display, are masks and totems cast in bronze: poetic images forged in a furnace. Rachid uses discarded objects and disused parts of machines, to create new human and animal forms. Here his interest in metal-working and African art coincides with the assemblage of found objects; one mask is constituted by a large model of the Eiffel Tower stuck into the end of a trumpet. Another has a jerry-can for a face, and the golden patina and surface-working of the bronze does not dispel the idea which this image creates: of a human mouth drinking oil.

Rachid is adamant that the artist has no country, his craft enables him to access cultural traditions across the world, the metal-working in Burkina Faso, for example, or China. Walking through the gallery, the last work you encounter is the largest and most striking work, which stands in front of a large bay window, through which the sounds of Madison Avenue can be heard: a tree in wood and bronze, masks hanging on chains from its branches. This is Strange Fruit - it is, Rachid says, a tribute to Billie Holiday and the city where she lived – and here is the link between the forging of metal and the fixing stare which communicates to its object the belief that it is foreign, unwelcome.

Rachid Khimoune’s work is on display at Friedman & Vallois, 27 E 67th St and Madison Av, NYC, until 21st December.

Rachid Khimoune in NYC

Rachid Khimoune grew up in a small mining town in Northern France where his Algerian parents had settled. It was there that he saw first hand the end of industrialisation: his father lost his job at the local mine and the family moved to the suburbs of Paris. The waves of urban immigration to the cities is a phenomenon important to Rachid’s work — his word for it is ‘transhumance’, or the seasonal migration of grazing flocks, their exodus to the city, a new forms of verticality — and he is particularly attentive to its effects in the capital cities of the world.

The Algerian war broke out before the move to Paris, and Rachid remembers how his family — who “felt French, completely integrated” — were treated by the other villagers. He remembers hearing about the hundreds of Algerians driven into the Seine by the French police in 1961. He speaks of a certain look they received, and connects this to his interest in the manhole cover — called, in French, ‘un regard’. This bizarre confluence of meaning, between the intangibility of the glance and the object wrought in iron, expresses a contradiction central to Rachid’s work. He is, he says, a maker of poetic images.

His most extensive work to date is Children of the World, a project long in development which culminated with an installment at the Bercy Park, Paris in 2001. To celebrate the transition into the twenty-first century, Rachid took from twenty-one different capital cities a ‘flesh of the street’ (he retranslates it ‘peau de la rue’). Moulding objects and collecting ephemera from various streets, Rachid put together twenty-one figures of ‘children’, ambassadors of cities entering a new century.

A more recent public project involved the installation of a thousand bronze tortoises on Omaha Beach in 2011, to commemorate the landings of Allied troops [top image]. There are several tortoises, in plastic and bronze, on the floor of the Friedman & Vallois gallery in New York — and I’m reminded of the tortoise in Huysmans’s novel A Rebours (Against Nature) whose shell is encrusted with jewels. Rachid’s tortoises, however, are cast in bronze and moulded by the shape of the helmets of the soldiers who fought in the D-Day campaign.

Tortoises, Rachid says, are used in North Africa to clean the house, at the same time as warding off “bad luck and evil spirits”. The tortoise is “a symbol of wisdom” and a metaphor for the longevity of war. The works reminds me of Jacob Epstein’s Rock Drill or Picasso’s work in bronze, and Rachid talks of its relation to art of the early twentieth-century: “they said never again, but every decade there are more wars.” In Mozambique Gonçalo Mabunda has also, recently, been making tribal masks from weapons.

Rachid’s newer works, also on display, are masks and totems cast in bronze: poetic images forged in a furnace. Rachid uses discarded objects and disused parts of machines, to create new human and animal forms. Here his interest in metal-working and African art coincides with the assemblage of found objects; one mask is constituted by a large model of the Eiffel Tower stuck into the end of a trumpet. Another has a jerry-can for a face, and the golden patina and surface-working of the bronze does not dispel the idea which this image creates: of a human mouth drinking oil.

Rachid is adamant that the artist has no country, his craft enables him to access cultural traditions across the world, the metal-working in Burkina Faso, for example, or China. Walking through the gallery, the last work you encounter is the largest and most striking work, which stands in front of a large bay window, through which the sounds of Madison Avenue can be heard: a tree in wood and bronze, masks hanging on chains from its branches. This is Strange Fruit - it is, Rachid says, a tribute to Billie Holiday and the city where she lived – and here is the link between the forging of metal and the fixing stare which communicates to its object the belief that it is foreign, unwelcome.

Rachid Khimoune’s work is on display at Friedman & Vallois, 27 E 67th St and Madison Av, NYC, until 21st December.

November 16, 2012

Friday Bonus Music Break

This summer’s Fuse ODG #ANTENNADANCE competition (“one person controlling the other using azonto movements”) courtesy of the Antenna smash hit resulted in some wild entries (Google it; H/T Jacquelin Kataneksza). Above: #TeamLONDON. And more good moves in the video for Congolese artist Lexxus Legal’s ‘Petits Congolais’ (off his “music record for kids”):

Early Sages Poètes de la Rue member Zoxea, repping Benin (his dad, Jules Kodjo, used to play for the national football team):

A collaboration between Danay Mariney and Kobi Onyame, who grew up between Accra (where he was born) and London, now based in Scotland. Video was shot in South Africa:

Tapping that London connection, here’s a dreamy video for Maka Agu (aka Ti2bs):

From Queijas (Portugal), new material by video artist, slam poet, MC and beatmaker Alexandre Francisco Diaphra (who goes by many names and claims many locations, among them Pecixe Island, Guinea-Bissau):

Promo video (interviews + outtakes) for the recently released Fangnawa Experience album, a collaboration between Burkina Faso-born Korbo (and his French music collective Fanga) and Moroccan Gnawa master Abdallah Guinéa (with his band Nasse Ejadba):

There’s also a new video for the Sierra Leonean Black Street Family, shot in Freetown. Hustling and tustling:

And to slow it all down a bit: two South African singer-song writers to end. A new video for Nomhle Nongoge’s ‘Ubuntu Bhako’ (references: soul, Eastern Cape, Simphiwe Dana, Zahara):

And Birmingham-based Laura Mvula’s live session for Hunger TV makes us look forward to hearing her debut album:

It’s Africans’ turn to help Norwegians

Who ever said Norwegians don’t have a sense of humor? Just in time for the holidays, a Norwegian group calling itself Radi-Aid has launched an appeal to ship radiators from Africa to Norway. Their cause is the plight of freezing children during Norway’s harsh winter months. It’s complete with a new music video, and incorporates all the right tropes (see here, here and here) — some people might miss the satire.

These people aren’t playing around though. Their effort is a serious critique of misguided development, and of the Western media coverage which often accompanies it. What they want:

1. Fundraising should not be based on exploiting stereotypes.

2. We want better information about what is going on in the world, in schools, in TV and media.

3. Media: Show respect.

4. Aid must be based on real needs, not “good” intentions.

It looks like we’re not the only ones to be fed up with poor spokesmen and seriously misguided aid efforts (H/T Rishita Nandagiri). Hallelujah; we here at AIAC couldn’t be more thrilled. We hope to interview the good folks at Radi-Aid (and the The Norwegian Students’ and Academics’ International Assistance Fund, the people behind it), so that we can come back to you with a feature on how they developed and funded their campaign. (Also, in preparation for spending this Christmas in Stavanger, I’m curious as to whether I might qualify for a radiator, or at least a new fleece & a bottle of Aquavit?)

Just in case you think this is an isolated incidence of Scandinavian brilliance, we were also referred today by Norwegian Magnus Bjørnsen to artist Morten Traaviks’ “pimp my aidworker” project, “a mock fundraiser for Western aidworkers.”

So stay tuned next week for more. In the meantime, we hope readers take the time to educate themselves on pressing issues in Norway. Because it is really cold there folks, but it’s also entirely lovely. And put the song on repeat.

November 15, 2012

10 African films to watch out for, N°11

And by ‘African’ we mean — made by African or diaspora directors, Africa-themed, or set in Africa. Don’t spend too much time pondering about that definition though. First up this week is Re-Emerging: The Jews of Nigeria, a documentary film (trailer above) by Jeff L. Lieberman about Nigerian Igbos who have adopted Judaism. (William Miles wrote a book about the same topic: Jews of Nigeria: An Afro-Judaic Odyssey; here’s an interview with Williams about his work.) Not unrelated to the film above, I came across this headline recently: “Moroccan film on Jewish Berbers sparks debate.” The film, Tinghir-Jersusalem: Echoes from the Mellah, is a documentary by French-Moroccan director Kamal Hachkar about the history of the Jewish Berbers of the small Moroccan mountain town of Tinghir who left during the 1950s and 1960s to resettle in Israel. The film is available in full (with French subtitles) on YouTube but here’s the English trailer:

Next up, Les Mécréants (“The Infidels”) is a Swiss-Moroccan production, directed by Mohcine Besri. The trailer is puzzling, and so is the synopsis: “On the order of their spiritual leader, three young Islamists kidnap a group of actors who are about to go on tour with their latest show. When the kidnappers arrive at the place of detention, they find themselves cut off from their base. A 7-day no exit situation [ensues], in which both sides are forced to live together, confront each other and challenge their mutual prejudices.” We’ll have to watch it:

There’s a couple of interesting film events happening this week. One of them this weekend in Namibia. Details here. Among the films that will be screened is Try, a short directed by Joel Haikali. Synopsis: 8 hours in Windhoek:

Showing at the Afrikamera festival in Berlin this week (which has a focus on ‘African women on and behind the screen’) is Ramata, the first feature film by Congolese director Léandre-Alain Baker. The film is set in Dakar (Senegal). No English trailer yet:

Ici on Noie les Algériens (“We drown Algerians here”) — also showing at Afrikamera — revisits October 17, 1961, the day when thousands of Algerians marched through Paris against the curfew imposed on them; a demonstration that saw a brutal crackdown by the French police leaving many demonstrators killed. Combining narrative and unpublished archives, the film traces the different stages of events, revealing the strategies and methods implemented at the highest level of the State (manipulation of public opinion, the systematic challenging of all charges, etc). Here’s a trailer (in French):

Remember François Hollande only recently became the first French president to recognize the State’s involvement, 51 years after the facts. (More and longer fragments here and here.)

Have You Heard From Johannesburg dates from 2010 but just last month won the Primetime Emmy Award for Exceptional Merit in Documentary Filmmaking. It is a series of seven documentaries, produced and directed by Connie Field, chronicling the history of the global anti-apartheid movement, that took on South Africa’s apartheid state and its international supporters who at the time considered South Africa an ally in the Cold War. The film’s website has a wide-ranging gallery of photos, profiles and links. The trailer:

The Dream of Shahrazad is a documentary film by South African director Francois Verster (remember his excellent ‘Sea Point Days’, which you can watch here if you haven’t), “[locating] political expression before, during and after the Egyptian revolution – and also within recent times in Turkey and Lebanon – within a broader historical and cultural framework: that of storytelling and music.” The film has recently been accepted for the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam’s co-production and co-financing Forum which hopefully means the production can be brought to a succesful end. There are more fragments on its website, but here’s the trailer:

Clara di Sabura is a film directed by Guinean José Lopes, inspired by Mussá Baldé’s famous poem with the same title — a comment on the lives of youth in (the streets of) Bissau. The opening scenes:

There’s no English subtitled version available yet, but if your Kriol (or Portuguese) is up to standard, you can watch the next parts of the film here.

And finally, another documentary. L’horizon cassé (“The broken horizon”) is a film by Anaïs Charles-Dominique and Laurent Médéa about the 1991 riots that broke out in the Cauldron, a neighbourhood of Saint Denis (La Réunion), after the popular TV channel Télé Freedom was shut down by the state and its founder, Camille Sudre, was taken to court. There’s no trailer yet, but here’s an interview with both the directors (in French), including some archival footage from the film:

In other festival news, there are encouraging reports from Amsterdam, where the Africa in the Picture film festival gets to keep some of its subsidies. And kicking off today in Nairobi is the OUT Film Festival, with a screening of I Am Mary, a documentary film about Mary, a volunteer with one of the GALCK member groups, Minority Women in Action, and an active participant in the fight for human rights for LGBTI persons in Kenya.

November 14, 2012

Bono’s Big Ideas (for Africa of course)

A new post on one of The Atlantic’s blogs breathily covers Bono appearing at Georgetown University in Washington D.C. to talk about Africa and foreign aid. It’s not clear why a publication like The Atlantic (or its online equivalent) is covering Bono giving a talk about Africa but the fact they covered it at all is part of the problem.

The post starts with a description of Bono’s attire. “Bono wore a rock star uniform of black jeans, a black v-neck t-shirt, black beads, and a black blazer, along with his trademark wraparound sunglasses.”

Bono’s appearance was to open this season of The Atlantic’s “Washington Ideas Forum.” We haven’t seen the full schedule, but, apart from the coverage that comes from inviting Bono, this is not promising. In fact, there are debates occurring right now in Washington, Addis Ababa, Mexico City, and around the world on how aid is delivered, and how it can be more effective. This week, the board of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB & Malaria is meeting in Geneva to decide on the future of their malaria initiative, among other decision points which will impact global health. The UK has announced it will no longer provide foreign aid to India, which is part of a larger debate around whether “middle income countries” should be eligible for aid at all.

Yet none of these issues are covered in the Atlantic’s international section.

Instead we’re treated to advice from Bono on how to change the world. He comes up with a “new” category of humanitarian: “the Afro-Nerd.” Then Bono said this: Instead of fighting companies or politicians, the young generation should fight against “all the obstacles to fulfilling human potential.”

I am sure that the recent deaths of 45 miners in South Africa had a lot to do with the behaviors of corporations, and that the price of drugs in developing countries is directly related to patents held by pharmaceutical companies usually based in the US or Europe (among other factors).

Perhaps one reason Bono is not interested in discussing economic power and its affect on development is that he unabashedly advocates for greater private sector involvement — without much thought given to promoting human rights in the private sector. According to the Atlantic piece, ‘He recently told Muhtar Kent, CEO of Coca-Cola, that if Coke signed on to Red, it would be able to update its old “Coke Adds Life” slogan to “Coke Saves Lives.”‘

Last time I checked, Coca-Cola had been involved in some egregious human rights abuses, and continues to contribute to policies which prevent people in Africa and elsewhere from accessing free, clean water — I think we can agree they don’t deserve such a zippy advertising slogan.

We won’t say much more about the practices (if you care, look here and here for example) of one of the main sponsors of the event, Bank of America.

To the editors of the Atlantic, we beg you — please no more articles claiming to discuss African issues which are just about rock stars turning up at an American university. And when it comes to foreign aid and development, give us real debates. The issues are too important not to get serious coverage.

And to Bono: you have a pulpit. Please use it more wisely. At least we’re not as unkind as a commenter on our Facebook page: “Oh, spare us your platitudes Bono — just sing.”

* Gif via Anneke Hannine (on our Facebook page).

November 13, 2012

Revolutions and Dancing

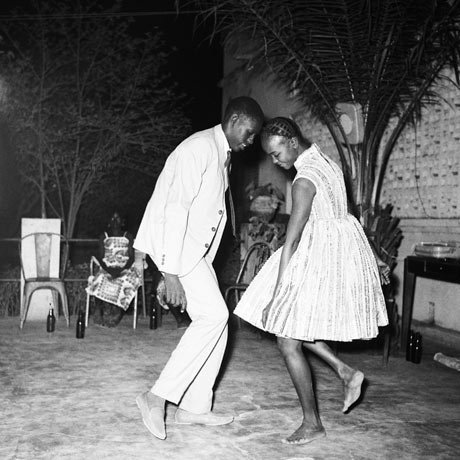

Malick Sidibé, Christmas Eve 1963.

In Egypt earlier this year I was taken by my host to a nightclub in downtown Cairo where I was introduced to a cosmopolitan group of friends — musicians, artists, poets — all drinking beer and dancing until the early hours of the morning. When the DJ played the songs of the revolution they punched the air, mouthing the words, and offering me spontaneous translations. Leaving the club around four in the morning we encountered a middle-aged man I’d been introduced to a few hours earlier — a painter, I had been told, and political satirist, he had impressive long, flowing hair, flecked with grey. Slightly unsteady on his feet, the satirist had his arm around a shorter man, a street-sweeper, speaking to him with great vigor. “He is saying,” my host explained, “the revolution is still alive inside the After 8 Club.” The other man, who had sparkling black eyes, said nothing.

*

This problem — the role of dancing (and pleasure more generally) in relation to radical politics — is exemplified by ‘You Was Dancin Need to be Marchin’, the 1976 funk classic by The Advanced Workers With The Anti-Imperialist Singers (written by Amiri Baraka and musicians from The Commodores, Parliament, Kool & the Gang).

*

The same problem emerges, more recently, in Hassan Khan’s film Jewel (2010), one of the most remarkable works of art in The Ungovernables, this year’s triennial exhibition at the New Museum (which we wrote about here). YouTube reveals an illicit video of the piece:

The occasion for this reflection is a new interview with Khan, recently published in the new ‘Platform’ (’004′) over at Ibraaz. Khan gives a really useful description of the inspiration and making of Jewel:

A few years ago (maybe 2006), I caught for a few seconds out of the corner of my eye two men dancing around a home-made speaker with a flashing lightbulb attached to it as the taxi I was in turned a corner on my way home. This moment (maybe it was the flashes of the lightbulb) initiated a sort of reverie or daydream in the taxi, where I imagined the whole piece as an artwork in one go. I remembered the piece when I got back home and noted it down. However, to achieve the piece I had to abandon the idea of replicating that daydream and to rediscover from scratch where this ‘moment’ could be found. [...] In the end the piece was choreographed [...] Some of the gestures were taken from street dances, others from fights, and others from ways of greeting.

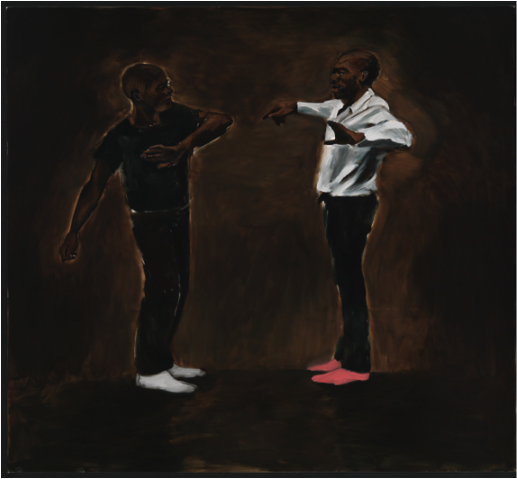

Still from Hassan Khan, Jewel (2010). Courtesy of the New Museum.

The way the actors were dressed was very important because it implied a specific position within contemporary Egyptian history: the older, heavier man in a brown leather jacket is the epitome of 80s street machismo — he is someone who maybe at that time made some money, smoked imported cigarettes, but is definitely lost nowadays. While the younger man dressed in a cheap approximation of office clothes is a university graduate probably from a small village and whose parents in some way (maybe unknown to even themselves) still subscribe to the ‘decent’ dreams of the 60s Nasserite state. [...] In the end, both of them are members of the crowd and the crowd is always many.

*

Another artist from the New Museum triennial is Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, the London-born painter, who will feature in The Progress of Love, an upcoming exhibition to appear simultaneously at the Menil Collection (Houston, Texas), the Pullitzer Foundation (St. Louis, Missouri) and CCA Lagos.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Milk for the Maestro (2012). Courtesy of the Chisenhale Gallery.

The exhibition promises to explore “the conception of love in Africa”, and the other twenty artists include Zoulikha Bouabdellah, Kendell Geers, Mounir Fatmi, Malick Sidibé (in whose native Mali civil war has politicised dancing) and Yinka Shonibare. There’s also this:

in Romuald Hazoumé’s new project the artist has founded a nongovernmental organization based in Cotonou, Benin, and is inviting his fellow Beninois to express love for self and others by making contributions to Westerners in hopes of helping them live better lives.

The mapping of the concept of love on the African continent is an intriguing prospect. We’re eager to know more.

*

Lastly — in the interests of semi-shameless self-promotion — my essay on dancing and revolution, the work of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Hassan Khan, has just been posted over here.

Kyle Shepherd X

This past summer I supervised fourteen New School graduate students for the school’s international field program in Cape Town. The students interned at a range of local organizations — a mix of NGOs, social movements and media organizations. You can watch a video (filmed by Dylan Valley) of the program here (watch from 1:33:27). One of the students, Clarissa Cummings (featured prominently in the video), interned at Chimurenga Magazine, where she wrote this profile of the pianist Kyle Shepherd (who has been featured on this blog):

Guest Post by Clarissa Cummings

Artists loathe hyper-intellectualism. Rationalization tends to eradicate emotion and surrendering passion becomes another way to pay the devil. But then there are those artists whose intellectualism is a birthright, not by choice and inescapable. Take, for example, jazz phenomenom Kyle Shepherd, raised in a provincial Cape Town home where the household language was colonial British speak and albums, from Bach to Monk, lined the shelves. If in this same home classical music poured from the radio every morning and there lived a matriarch, a violin player serious about education, how could an artist grow to not at least dabble in intellectualism? Odds are he can’t. Smaller odds are that the contradiction serves the art.

Kyle Shepherd makes no apologies for his urban aristocratic upbringing or the genetics of his cerebral trajectory. “No doubt about it, we were reading English novels and listening to classical music. And so I am thankful for that cause I was exposed to such great and very serious music at such an early age.” But at the present don’t bombard him with intellectual talk, at least as it pertains to music, because he says, “I’m not enjoying it.” It’s why he has been turning down opportunities to speak on conference panels and most recently came to the decision to decline interviews. Kyle blames all this talk for creating labels that do their job at reasoning away artistic freedom. “From my experience from music, labels are so dangerous. Labels are for programmers, festival producers. The thing is I hate when people push me into Cape Jazz.” This is the label that has Kyle retreating deeper into theories of disconcert. Transformation is a form of retaliation.

Only five years ago at the age of 21 Kyle released his first jazz album, fine ART. It was the beginning of what he saw as a trilogy that ended with this year’s aural travelogue, South African History X! The holy trinity of Kyle’s three albums, all of which carry the notes of South Africa’s historical ebb and flow, has made him the current messiah of Cape Town jazz. “That kind of bullshit,” he bristles, “I’m not into that. The ‘architect of cape jazz.’ Whatever. My mission as a musician is about personal development and not being pigeonholed. The music that I am playing now is different. And I’m gonna be subjected to what people think of me. It certainly takes me off the path but I’m more about the personal commitment.”

If Kyle’s rejection of what he has done so well, so particularly correct, appears to be a spoiled reaction to the acclaim, his commitment to evolving at least provides the context for his condemnation. “I’m moving on to bigger stories, bigger ideas, by that I mean ideas that are not subjected to a place or limited by a country. I’m trying to now use music that tells a bigger story a more worldly story.” Kyle doesn’t reject what he was. His current concern is with what he is becoming. “I’m working hard to transcend this whole cultural, race thing. It’s great to have that identity, it ties into those first three albums. I was all about discovering my identity. Now that I’ve discovered it, I’m trying to transcend it.”

Despite the pitfalls involved in artistic revolution (just ask Lauryn Hill), change is an inevitable part of the process that Kyle has claimed since his youth. Confidence is a common privilege of intellectual rearing. At sixteen he experienced a cultural awakening, came home one day and announced he was forfeiting British speak for a more colloquial Afrikaans. Soon after, he taught himself to play the piano and shed twelve years worth of identity as a classical violinist for that of jazz musician. “When I first wrote jazz, it was like home. I knew. I could relate to it, like someone speaking my language and it was a breath of fresh air for me. When I heard jazz I was like yeeeah and I knew. It was the energy and spiritual part of it. The opportunity to express. I could feel it before I was able to put words to it.”

If Bukowski was correct, an “intellectual says a simple thing in a hard way. An artist says a hard thing in a simple way.” But the complexity of Kyle raises contradiction because he is saying some hard things in a hard way. If the reputation Kyle has as the jazz voice of Cape Town now weighs heavy like a shackle, it is in some part his own fault. While his first two albums are technically refined, delicate bursts of emotion can be heard in the space between the instruments. Near the end of the track, “Dylan Goes to Church”, there is more drama in the quiet that quickly peeks out between the chanting chorus and the horn. His songs don’t build upon each other as much as they whittle their way across breaks. The listener is witness to Kyle in the process of piecing the puzzle together. It is why South African History !X stands distinctly apart from his previous works. In this project Kyle comes to us with the puzzle already complete. He knows which keys will pound out the feet of marching laborers and introduces the Xaru, a traditional Khosian bow instrument, as a significant contribution to musical structure on “Xam Premonitions”. What he delivers is undeniably Cape Town and that’s the way he wanted it. If Kyle is grappling it doesn’t seem to show. And it’s this type of confidence that makes it hard to peel your eyes away from his artistic evolution. It’s like a theory collision about to happen. Something has to happen. Kyle is restless. “When I wake up, my biggest goal is ‘I want to be moved today.’ And 5 days out of 7 I’m not moved.”

It might be Kyle’s comfort with the ramifications of his transition that most unnerves his fans and the critics. But if there is any solace he can offer it will involve a re-imagining of what is jazz? Kyle says, “The plain answer to that I don’t know.” The labels have gotten so out of hand he makes no effort to keep up. He self-identifies as an “improvisational” musician and says that all of his stage performances are performed in the moment. “In the improvisational world, or jazz, or whatever you wanna call it, I call it improvisational…there is no going back, there is no editing. It’s why I truly believe that jazz, or improvised music, which people don’t call jazz anymore, music with inspiration on the level of jazz, is the most evolved form of music in the world. I really believe that. The thing is, you have the framework which is the song and then you have to improvise. And that improv is largely based on doing things you’ve studied before, but most of it is created in the moment.” Imperfection is often brutal to the artist’s ego. But Kyle, perhaps through confidence or perhaps by way of intellectualizing, is accepting. “Imperfection is part of it, that’s the the beauty, the realness, of this music. It relates so closely to be human. It is a reflection of who we are in many ways because everyone improvises. We improvise our way through life. Creating something of the moment and only of that amount. That’s the beauty of it. That’s the the danger of it.”

Photo Credit: Kyle Shepherd’s Facebook Page.

Zambia’s Gossip Girl

Even as a child, I knew Zambia was a media dictatorship. No one dared say too much that criticised the government; and anyway, where did we get our daily news? Two sources — a nationalised newspaper, and a nationalised television station, both of which were (and apparently continue to be) government mouthpieces. The ZNBC news at 7pm and 9pm dutifully rattled off the schedule of meetings that party members attended, panning the bored audience of attending ministers (some soundly sleeping) as Kaunda or some other dignitary expounded on the merits of the One-Party Participatory Democracy. Sneaking in a shot of a sleeping party member during a 3-hour speech was as revolutionary as things were going to get.

Sean Jacobs, Marissa Moorman and I will be part of a roundtable on “Politics and Popular Culture” at the upcoming African Studies Association in Philadelphia on November 29. I’m sure Zambia will come up, and that someone will make a reference to James Ferguson’s work on Internet culture in late 1990s Zambia.

Like everywhere else, I often fear that not much has changed for Zambia’s media: we have more mobile phones, but not people who have access to much political information, nor the means of participation, except the occasional strike to protest mine conditions. The vast majority of Zambians do not have access to Internet sources, and have to rely on the television station, ZNBC, and the newspapers Times of Zambia and Daily Mail — each of which seems to compete for uniformity and blandness in reportage prizes.

However, for a small number of people, perhaps an elite group that includes those Zambians who live abroad, the well-connected, and those in the tiny segment of the Zambian upper-middle class, Zambia Watchdog (ZWD) has provided a steady stream of criticism. People tend to make jokes about the relevance of ZWD, but it’s not only addictive because of its constant updates, but reassuring because it asserts its rightful place outside the monolith of official control. And apparently, like the U.S. teen-drama Gossip Girl, it has friends and informants in high, low, and all places, who seem to vie for the right to feed the site with insider’s insights and the latest shock-story.

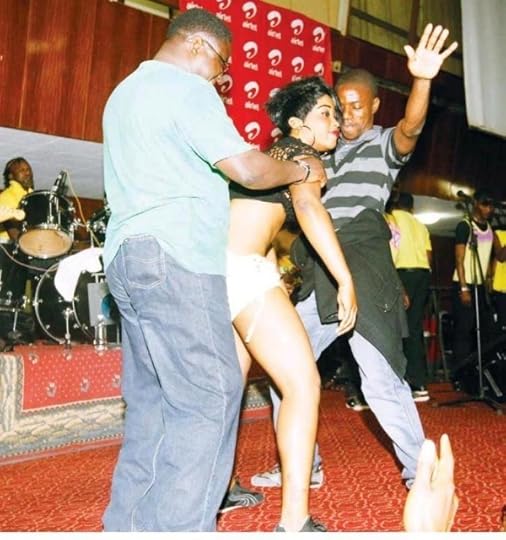

We’ve grown to love serious reportage coupled with compromising photographs and cheeky headlines, such as “Kambwili grabs Roan golf club, turns it into grazing field for his cows,” replete with a stock image of the enormously pot-bellied Sports Minister Chishimba Kambwili, and a story supplied by ‘concerned citizens’ detailing how he appropriated the Luanshya-based Roan Antelope club to feed his crew of cows and goats. And check out this recent piece covering a possible “a serious electoral showdown in Solwezi should [the] party go ahead with its latest plans to hound out those serving in the current government” (boring!) with an image of this big-talker, Solwezi East MMD member of parliament Richard Taima gyrating his crotch against the seemingly willing behind of a half-clothed woman in an apparent public dance-off (there’s a band playing in the background, while another party member, ‘Playboy’ Stephen Masumba, throws some display-dance moves to the woman’s front). Obviously, we all clicked on the image [above] and were treated to a story about how minor political rivalries are playing out in the far corners of the country.

Recently, however, it seems that ZWD had made gains in influence — perhaps there’s more access to the Internet, bringing with it a larger readership. The site has become the target of a threat of denial of service (DDoS) — allegedly by the government — and the Zambian Registrar of Societies, Clement Andeleki, had given ZWD 48 hours to provide a physical address or face de-registration. The Zambian government doesn’t just resort to empty harassment; it takes censorship seriously, using K5 billion or US$1 million to send police and security staff abroad to learn to hack websites. In April this year, ZWD listed several further measures taken by the government to crackdown on Internet users in Zambia.

However, despite the general taboo hanging over ZWD’s site, those proclaiming love and loyalty to motherland and party also seem to check the site as obsessively as the rest of us. During a Lusaka Council meeting in October, Finance Deputy Minister Miles Sampa and Minister in Charge of Chiefs Nkandu Luo were both caught on camera, browsing ZWD. And to add to this hilarity, mirroring plotlines of Gossip Girl (where New York City’s fashionable Upper East Side players frequently check-in to see if they remain relevant while threatening to ‘take-down’ the cruel person behind the Gossip Girl site), Sampa and Luo were spotted (and recorded) browsing ZWD only days after the site was threatened with de-registration. Perhaps they were gathering evidence for the government’s case against critical media.

We contacted ZWD via the email address they provide; the editors wrote back promptly: “We are humbled to note that we provide a platform where frustrated Zambians are able to vent their anger online. We feel it’s better than using pangas and machetes.” (Email, by the way, is the only way to contact ZWD editors, seeing as they have ”to protect [them]selves and [their] work from people who have been trying to destroy what [they] do and harm [them]. These include drug dealers and their lawyers, political mercenaries, corrupt public officials and some journalists.”)

Note to Michael Sata and his hounds: controlling the media may have worked for Kaunda, and even for his recent successors. But really, man, it’s not going to work for something as popular and entertaining as ZWD, especially in a country with no other expressive outlets for critiques of power and public irony. Like Chinese Internet users, people will find a way. Or they might take up pangas and machetes.

One commentor, having read the report on Sampa and Luo’s browsing habits, noted not only the uselessness of the official papers (people grab a ‘borrowed’ copy to check out the daily cartoon, or to see what the adverts are offering), but also the relevance of ZWD:

“In case you are under rating the substance and existance of the watchdog. Some of us we start with the watchdog then proceed to the office read a borrowed post newspaper just to check chocklet’s catoon. I may buy the daily mail [goverment owned daily paper] for adverts. But I don’t forget to re-check the watchdog just incase of any breaking news. Even before going to bed, I check the breaking news. Keep it up ZWD.”

November 9, 2012

Friday Music Break

Hello! Boima here, and I’m back helping out with the Friday music break. A Haitian Rara (not Ornette Coleman) sampling rap/poem by Hyperdub affiliate The Spaceape got me excited this week, so that’s my lead off pick — above! Not only do the U.S. and China have political happenings this month, but Sierra Leoneans go to the polls next week as well. Bajah and the Dry Eye Crew put out a song appealing for peace amongst young people, who are often conscripted by politicians to carry out violence during election periods. Back in Sierra Leone, the musical messages to hold politicians accountable reassuringly continue:

Meanwhile a young diaspora Sierra Leonean is making noise in the U.K. with an electro-pop sound and Nikki Minaj-esque video:

M.anifest releases a NICE neo-Hiplife video with the beautiful Efya off his album Immigrant Chronicles: Coming to America:

His countryman Sway goes full Akon this week, dropping a video for an electro pop collabo with Mr. Hudson and Crystal Waters! But I can’t help wonder, what happened to Up Ur Speed Sway?

Awadi goes to Medellín, Colombia to sing about revolution. I wonder if the FARC is in on this:

Which reminds me that I had the pleasure to spend a weekend with Medellín based, Pacifico reppin’ Explosión Negra in Philadelphia recently:

New high quality Liberian video for a not-so-Hipco rap:

I’m realizing that I kind of over-Hip Hopped this Music Break, so here’s a nice change of pace from Portugal based singer with Cape Verdian roots Dino D’ Santiago featuring Pedro Mourato and Gileno Santana:

And finally, London based A.J. Holmes, who’s learned from and collaborated with musicians from classic Sierra Leonean bands like Super Combo and the S.E. Rogie band, goes to the sea:

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers