Revolutions and Dancing

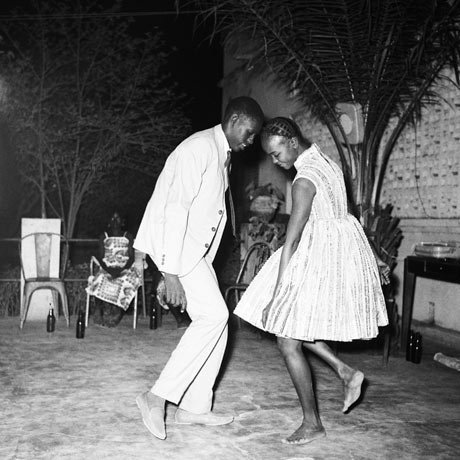

Malick Sidibé, Christmas Eve 1963.

In Egypt earlier this year I was taken by my host to a nightclub in downtown Cairo where I was introduced to a cosmopolitan group of friends — musicians, artists, poets — all drinking beer and dancing until the early hours of the morning. When the DJ played the songs of the revolution they punched the air, mouthing the words, and offering me spontaneous translations. Leaving the club around four in the morning we encountered a middle-aged man I’d been introduced to a few hours earlier — a painter, I had been told, and political satirist, he had impressive long, flowing hair, flecked with grey. Slightly unsteady on his feet, the satirist had his arm around a shorter man, a street-sweeper, speaking to him with great vigor. “He is saying,” my host explained, “the revolution is still alive inside the After 8 Club.” The other man, who had sparkling black eyes, said nothing.

*

This problem — the role of dancing (and pleasure more generally) in relation to radical politics — is exemplified by ‘You Was Dancin Need to be Marchin’, the 1976 funk classic by The Advanced Workers With The Anti-Imperialist Singers (written by Amiri Baraka and musicians from The Commodores, Parliament, Kool & the Gang).

*

The same problem emerges, more recently, in Hassan Khan’s film Jewel (2010), one of the most remarkable works of art in The Ungovernables, this year’s triennial exhibition at the New Museum (which we wrote about here). YouTube reveals an illicit video of the piece:

The occasion for this reflection is a new interview with Khan, recently published in the new ‘Platform’ (’004′) over at Ibraaz. Khan gives a really useful description of the inspiration and making of Jewel:

A few years ago (maybe 2006), I caught for a few seconds out of the corner of my eye two men dancing around a home-made speaker with a flashing lightbulb attached to it as the taxi I was in turned a corner on my way home. This moment (maybe it was the flashes of the lightbulb) initiated a sort of reverie or daydream in the taxi, where I imagined the whole piece as an artwork in one go. I remembered the piece when I got back home and noted it down. However, to achieve the piece I had to abandon the idea of replicating that daydream and to rediscover from scratch where this ‘moment’ could be found. [...] In the end the piece was choreographed [...] Some of the gestures were taken from street dances, others from fights, and others from ways of greeting.

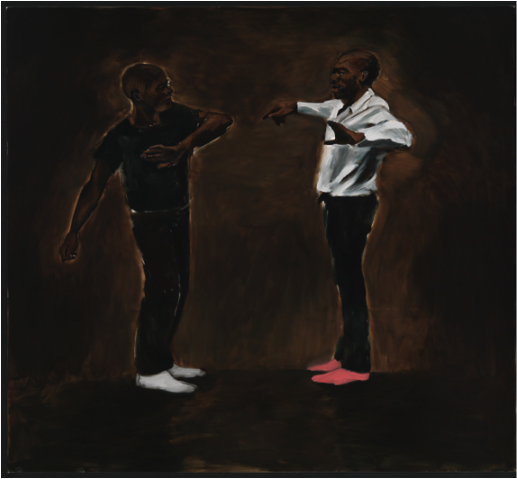

Still from Hassan Khan, Jewel (2010). Courtesy of the New Museum.

The way the actors were dressed was very important because it implied a specific position within contemporary Egyptian history: the older, heavier man in a brown leather jacket is the epitome of 80s street machismo — he is someone who maybe at that time made some money, smoked imported cigarettes, but is definitely lost nowadays. While the younger man dressed in a cheap approximation of office clothes is a university graduate probably from a small village and whose parents in some way (maybe unknown to even themselves) still subscribe to the ‘decent’ dreams of the 60s Nasserite state. [...] In the end, both of them are members of the crowd and the crowd is always many.

*

Another artist from the New Museum triennial is Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, the London-born painter, who will feature in The Progress of Love, an upcoming exhibition to appear simultaneously at the Menil Collection (Houston, Texas), the Pullitzer Foundation (St. Louis, Missouri) and CCA Lagos.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Milk for the Maestro (2012). Courtesy of the Chisenhale Gallery.

The exhibition promises to explore “the conception of love in Africa”, and the other twenty artists include Zoulikha Bouabdellah, Kendell Geers, Mounir Fatmi, Malick Sidibé (in whose native Mali civil war has politicised dancing) and Yinka Shonibare. There’s also this:

in Romuald Hazoumé’s new project the artist has founded a nongovernmental organization based in Cotonou, Benin, and is inviting his fellow Beninois to express love for self and others by making contributions to Westerners in hopes of helping them live better lives.

The mapping of the concept of love on the African continent is an intriguing prospect. We’re eager to know more.

*

Lastly — in the interests of semi-shameless self-promotion — my essay on dancing and revolution, the work of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Hassan Khan, has just been posted over here.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers