Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 516

October 24, 2012

My favorite photographs N°9: Halida Boughriet

On show at the Islamic Cultures Institute in Paris until January, 50 Years of Reflection, is an exhibition of the work of French-Algerian artist Halida Boughriet. It is one of many recent installments in France commemorating Algeria’s half-century of independence. Boughriet lives and works in Paris, where she has made videos, created installations, and continues to broaden her photographic portfolio. Below are her 5 favorite photographs, and her comments on how they came into being.

On show at the Islamic Cultures Institute in Paris until January, 50 Years of Reflection, is an exhibition of the work of French-Algerian artist Halida Boughriet. It is one of many recent installments in France commemorating Algeria’s half-century of independence. Boughriet lives and works in Paris, where she has made videos, created installations, and continues to broaden her photographic portfolio. Below are her 5 favorite photographs, and her comments on how they came into being.

Mémoires dans l’Oublie (Memories in Oblivion)

Photography often borrows its topics from painting, a tradition inherited from Gustave Courbet. The photo series ‘Memories in Oblivion’ (which was part of the ‘How to tame ghosts’ exhibition, curated by Bonaventure Soh Ndikung at SAVVY Contemporary gallery in Berlin earlier this year), are images of great historical figures seen through a reversed lens –one that takes ownership of the stigma attached to each of them. This aesthetic approach becomes a ritual and an act of portrayal. It is an approach that is critical of Orientalism, and inseparable from reality and its humanism — contrary to the Orientalist representations that didn’t see the human, and were mostly concerned with their own projections and lust.

‘Memories in Oblivion’, the first photo in the series (above), is still part of a work in progress. It is part of a series of portraits of widows who have suffered the violence of the war in Algeria. I was born and raised in France by my Algerian parents, and this period is an intrinsic part of my family’s history. These women in the portraits represent a collective memory: they are the last witnesses. However, when one evokes the war in Algeria, one never thinks about them, mainly because official history, nor popular imagination of the war includes them. However, these widows were very much part of that history, and that war: they have suffered, resisted, lost their husbands. I find them beautiful, regardless of their age, and I wanted, in my project, to help re-include them as a significant part of French-Algerian history in both official and popular imaginaries.

This series also relays the journeys made by these older men and women, rather than a static history in which they remain stuck. Their collective passage from one place to another resonates throughout this series of paintings.

Here, also, I wanted to use the colors within the image and transform them into the subject of the photographs, re-appropriating the surface of the image. Light is very important to my work in these portraits, though I am, of course, interested in the faces of the women and men — light and colour help draw attention to the depths of history written on their bodies, and the silences surrounding them. I have photographed all of them in the same position: lying on their side, with a sort of aura that falls on them in a relatively dark space. I am inspired here by the orientalist paintings of Ingres, Boucher and Fragonard. I love the contrast between the sensuality, the lasciviousness of their posture and the twilight appearance of the room. The halo reminds me of Bernini sculptures. But my work is a kind of reinterpretation of the ‘Great Masters’ of Europe who wrote our bodies into the ‘western’ imaginary; I work with Orientalism, and against it at the same time.

These photographs of retired Algerians, like the one below, were taken in French “Sonacotra” homes (homes for migrant workers, social residences, guest houses, hostels, shelters for asylum seekers, etc.). What the subjects in the photos have in common is that they’re all left to their own. They are the representatives of an era ending.

Maux des Mots (Problems with Words)

The objective of an artist residency in Jijel (Eastern Algeria) in which I took part not too long ago, was first to collect texts on the notion of guilt and to transcribe them in red ink on the surface of a male and female back, meaning two different entities. The intention was to leave a space to speak, to write, somehow, in the form of a quest for redemption, but also towards human existence, its doubts and fears, or to rethink a collective responsibility.

Reflections around this question of guilt have helped me to collect testimonies by artists, playwrights, directors, slammers and poets. In Jijel, I photographed these actors with the help of Mustapha Ghedjati who worked on the calligraphy on the surface of the backs of the actors.

The photos were taken in many different places, including at the edge of the sea, as a purification to wash away the evils of the world. But my choice of photos here is this diptych in which the individuals have their bodies washed by a slight movement of the water, lapping over their nude backs, the ink slowly erasing. The rhyme on the man’s back is more dense than the one on the woman’s. Some changes of color allow for a unification of these two different worlds. The sepia harmonizes both and takes over their reality. This photographic diptych, which is now part of the MAC/VAL collection (located in the Paris commune of Vitry-sur-Seine), is printed on dibond bronze, which again modifies the photographic effect.

Artists have traditionally produced works intimately linked to our collective history. Some of these works were intended to remind viewers of the important role played by those who fought for freedom–this is especially true for those of us who are both French and Algerian. I want my work to be both incisive and engaging; as an artist, I feel that it is important to be a part of how audiences re-shape their memory as they readjust their opinions in light of new information about their history.

Paul Ricœur refers to this ambiguity of the concept of an oeuvre. An oeuvre, a work, is what we do, what we create and what we make of our lives … what we are. I just know that I have always wanted to work on reality, memory, man. Through art, I want to live my time, my presence. I have been making photographs for 10 years and I hope to make something universal. My multifaceted productions are marked by some violence, informed by my own story and those of others.

What would happen if you made a film about a key figure in Finnish history and cast Kenyan actors?

UPDATED: ‘The Marshal of Finland’, a new film about that country’s first post-World War II president and national icon (and controversial war figure), Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, has left Finns divided. At the heart of the “debate” is the fact that the film was shot in Kenya, with an entirely Kenyan cast playing the Finnish roles. ‘The Marshal of Finland’ is described as “combining traditions of African storytelling and biographical elements of Mannerheim.” The characters speak Swahili and some brief English. Most of the production crew were Kenyan (the director is a Kenyan, Gilbert Lukalia). Much of the negative reaction to the film, disguised as questions about costs to the tax payer, really revolved around black actors playing Mannerheim and his wife and mistress.

Finnish nationalists also felt insulted that a national hero was played by non-Finns. Finnish media made much of the fact that “a dark-skinned actor” played Mannerheim. (The lead actor, btw, goes by Telley Savalas Oteinno). The Finnish producer has received threats.

Here’s the trailer:

The production was a collaboration between the Finnish public broadcaster YLE who forked out the money for it, a Kenyan production team (including actors, director and writers) who largely created the film, and an Estonian production company which has been in charge of the intercontinental link up.

The film was aired on Finnish TV last month.

The whole media circus that followed in Finland — mainly directed by tabloids newspapers — has created this unquestioned and inaccurate image of a nation feeling insulted, all based on anecdotal evidence, i.e. online comments in story threads. Examples: “How can we waste money on such?!”, “Our license fees go to some foreigners,” the comments read.

The film is still available online, so you can watch and judge it for yourself — if you’re fluent in Finnish (for the subtitles) or Swahili.

What would happen if you make a film about a key figure in Finnish history and cast Kenyan actors?

UPDATED: ‘The Marshal of Finland’, a new film about that country’s first post-World War II president and national icon (and controversial war figure), Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, has left Finns divided. At the heart of the “debate” is the fact that the film was shot in Kenya, with an entirely Kenyan cast playing the Finnish roles. ‘The Marshal of Finland’ is described as “combining traditions of African storytelling and biographical elements of Mannerheim.” The characters speak Swahili and English. Most of the production crew were Kenyan (the director is a Kenyan, Gilbert Lukalia). Much of the negative reaction to the film, disguised as questions about costs to the tax payer, really revolved around black actors playing Mannerheim and his wife and mistress.

Finnish nationalists also felt insulted that a national hero was played by non-Finns. Finnish media made much of the fact that “a dark-skinned actor” played Mannerheim. (The lead actor, btw, goes by Telley Savalas Oteinno). The Finnish producer has received threats.

Here’s the trailer:

The production was a collaboration between the Finnish public broadcaster YLE who forked out the money for it, a Kenyan production team (including actors, director and writers) who largely created the film, and an Estonian production company which has been in charge of the intercontinental link up.

The film was aired on Finnish TV last month.

The whole media circus that followed in Finland — mainly directed by tabloids newspapers — has created this unquestioned and inaccurate image of a nation feeling insulted, all based on anecdotal evidence, i.e. online comments in story threads. Examples: “How can we waste money on such?!”, “Our license fees go to some foreigners,” the comments read.

The film is still available online, so you can watch and judge it for yourself — if you’re fluent in Finnish or Swahili.

Finland’s history of war in Swahili

People can feel quite protective of their histories. And can get a tad sensitive about these things too. That is the premise with which I started looking at the film ‘The Marshal of Finland’. The production is collaboration between the Finnish public broadcaster YLE who forked out the money for it, a Kenyan production team (including actors, director and writers) who largely created the film, and in between an Estonian production company which has been in charge of the intercontinental link up.

People can feel quite protective of their histories. And can get a tad sensitive about these things too. That is the premise with which I started looking at the film ‘The Marshal of Finland’. The production is collaboration between the Finnish public broadcaster YLE who forked out the money for it, a Kenyan production team (including actors, director and writers) who largely created the film, and in between an Estonian production company which has been in charge of the intercontinental link up.

The film is about Finland’s only ever war marshal, and former president, Carl G.E. Mannerheim.

Public foolishness ensued when it was premiered on TV last month. The debate around it is divided into two parts: one where we hadn’t yet seen the film and speculated a lot, and another when the film was broadcasted and made available online.

Is it art or just a provocation? Times are such that strong elements of scepticism towards multiculturalism are at the centre of national political debate. A loud minority that stretches from value conservatives to counter jihadists have come in with a bang and pretty much everyone would venture a guess that a film like this would upset them great deal. And it did. Only, it’s not so easy because there never was a Kenyan production company which in some Monday staff meeting decided to make a film about some northern geezer with many medals on his chest. It was a Finnish idea. According to the producer, who has received threats and some inappropriate envelopes of unwanted matter, the concept was born when his Estonian colleague introduced the idea of making a film in Kenya. Any film. Said colleague had contacts in the East African film industry and he was keen to produce something in collaboration. It was the Finnish producer who then had suggested the topic of Mannerheim and with material and information provided from Finland, the Kenyan crew wrote and cast a film.

The whole media circus that followed — mainly directed by the tabloids — has created this unquestioned and inaccurate image of the nation feeling insulted, all based on anecdotal evidence. When I say anecdotal evidence, that’s posh for a few angry people on those papers’ comment threads. “How can we waste money on such?!”, “Our license fees go to some foreigners,” the comments read. Then it was said that the whole film cost 10 000 €. That was too little. Then it was said that while the film was cheap, simultaneously there was a documentary produced and that was more costly — according to these shaky sources it was said to have been 150 000 € — but at no point was it elaborated on how much such documentaries cost in general.

Offence is being taken as liberally as it’s being given. This 43 minutes film has been a mother lode.

It is still available online, so you can watch and judge it for yourself — if you’re fluent in Finnish or Swahili.

October 23, 2012

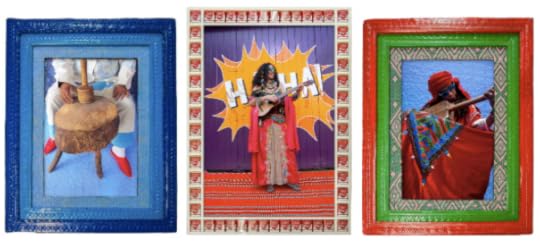

Hassan Hajjaj’s Rockstars

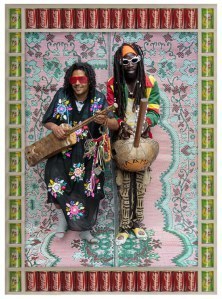

Hassan Hajjaj’s first memories of photography are from his childhood in Morocco. His mother would occasionally dress him in clothes sent from his father in England, cover him in perfume and take the whole family to the local photography studio for a family portrait. Then there were the street photographers in Lamache, the harbour town where he lived until the age of fourteen, “who would take pictures of you on a plastic horse, wearing cowboy hats and so on…” There is a similar colour and spontaneity to My Rockstars: Volume 1, a series of studio portraits Hajjaj has been working on since 1998, exhibited for the first time at The Third Line gallery in Dubai last month.

Hassan Hajjaj’s first memories of photography are from his childhood in Morocco. His mother would occasionally dress him in clothes sent from his father in England, cover him in perfume and take the whole family to the local photography studio for a family portrait. Then there were the street photographers in Lamache, the harbour town where he lived until the age of fourteen, “who would take pictures of you on a plastic horse, wearing cowboy hats and so on…” There is a similar colour and spontaneity to My Rockstars: Volume 1, a series of studio portraits Hajjaj has been working on since 1998, exhibited for the first time at The Third Line gallery in Dubai last month.

This is only the latest in what has been a busy few years for Hajjaj, exhibiting his work in Europe, Africa and the Middle East: in 2009 his photographs were featured in the Bamako Rencontres Biennale, this year he exhibited work in Riad Yima, a house he designed himself, featured in the Marrakech Biennale.

The research for My Rockstars started in Marrakech, where Hajjaj lives for part of each year, capturing shots of the people he meets: “not just musicians but the snake charmer, henna girl, bad boy, male belly dancer … I wanted to give them a backdrop and started from there.”

His sitters now have more than a backdrop, they often wear clothes he has designed, standing in spaces totally covered by patterns he has chosen, the photographs are eventually set in a frame he has constructed.

His sitters now have more than a backdrop, they often wear clothes he has designed, standing in spaces totally covered by patterns he has chosen, the photographs are eventually set in a frame he has constructed.

If his skill-set is impressive it isn’t thanks to any formal education. After leaving school, Hajjaj was unemployed and between “shitty jobs” for “five to six years”, during which he started organising parties and events with friends, booking djs and bands to play. He opened a shop called Rap in Covent Garden in London with his wife, Vanessa, and started to sell clothing designed by his friends. Seeing what sold well, he would buy the material and work out how to make them himself, learning gradually, “how not to be scared of doing stuff, of failing.”

He worked as a stylist for a fashion photographer friend and learnt about film production working on promo videos with another. In 1989 he bought a camera from a friend and started to take pictures, “just now and then, for myself.” They did some art shows at the shop, “that was my schooling,” but still he never produced anything under his own name.

He worked as a stylist for a fashion photographer friend and learnt about film production working on promo videos with another. In 1989 he bought a camera from a friend and started to take pictures, “just now and then, for myself.” They did some art shows at the shop, “that was my schooling,” but still he never produced anything under his own name.

In the late nineties he opened a tea shop with his brother and sister, and did some designs for the interior, and it was soon after that, he says, “I started doing stuff I wanted to present as art work.”

Several years later, his most enduring and well-known project until that point, he started to design Andy Wahloo, a bar in Paris he planned with his friend Momo, which opened in 2003. The name is partly in tribute to Warhol, whose influence isn’t difficult to see in his designs; it also puns on the Arabic for “I have nothing”, and gestures towards his tendency to redesign found materials, turning a crate into a seat, a lightbox into a table.

It was at this time he first met Rose Issa, whose gallery now represents him, and she started to encourage him to make serious art. At this stage his work becomes more personal, and he starts to photograph people he knows, who trust him. Was this a natural move? “Art,” he says, “is just like fashion, music, film.” But he wanted to document life around him, in London, his friends who might “never make it into the mainstream.”

Take, for example, friends, Simo Lagnawi — gnawa-player, member of London-based “eclectic groove adventurers” Electric Jalaba — and Paris-based Kora-player Boubacar Kafando (left): “the stuff they’re wearing is all theirs, apart from their sunglasses, shoes, headband…”

Take, for example, friends, Simo Lagnawi — gnawa-player, member of London-based “eclectic groove adventurers” Electric Jalaba — and Paris-based Kora-player Boubacar Kafando (left): “the stuff they’re wearing is all theirs, apart from their sunglasses, shoes, headband…”

The frame around this portrait is a neat shelf crammed with 7 Up and Coca-Cola cans, symbols of a burgeoning import market, the artist explains, designed to “trap the eyes, bring the viewers to your work.”

The design of the frame is important, he says, “I’m trying to create something which has as much of my identity as possible … something that is fresh in Europe and Africa … it’s like when you see the jars and the sweets in the shop as a child.”

Do you feel there’s a difference, I ask, presenting work in Morocco and London?

The frames, he says, give people something “quite immediate” to react to, whether it is in Morocco or London. They harness “the power of brands as a sense.”

He always finds it funny when he is introduced as “the guy with the Coca-Cola frame”. These brands give his work an international identity, though it is still context-dependent:

“Growing up, guests would come over and you would go and buy the bottle … Now it’s more regular, but that dream of wealth … You go to a Macdonalds in Washington DC, and it’s ghetto, rough, but if you go to Morocco it’s middle class.”

There are plans for a London installment of his Rockstars for next year, an exhibition at Rose Issa’s gallery with a nightclub afterwards. I wonder if he would design the club too — with the opening of Silencio in 2011, the interior designed by David Lynch, it seems that the nightclub is a new model for a total work of art. I tell him it sounds as if he wants to design the whole world.

“I wish I could!”

Rockstars has affinities with the work of photographers like Samuel Fosso and Seydou Keita, but Hajjaj doesn’t talk much about his influences. Malick Sidibe’s photos of Malian nightlife made a big impact on the work, he says: “those are cool, important pictures.” But where does he go, I ask, to find a similar scene in London?

“I’m lucky, I’ve been on this earth quite a while … so I don’t have to go out too far … I find, close to what’s around me, enough people to document.”

As if to prove this, I hear some friends enter his studio and one shout over, “can I get a photo in this hat?” A woman ducks her head into the Skype window and says hello, sporting a hat which sprouts large artificial flowers.

“That’s why it’s called Volume One: this is a life thing for me, I just don’t have enough time.”

“The intellectual home of the democratic left”

In 2012 the University of the Western Cape in Cape Town turned fifty. That milestone alone demands retrospection and celebration given UWC’s place in South Africa’s higher education set-up. But such celebration also comes with pitfalls: “Histories of universities are difficult undertakings because they open onto such complex questions of our modern subjectivity and its relations to the exercise of power, not to mention the internal dynamic which proves elusive at the best of times,” write the editors in the introduction to the new edited volume, Becoming UWC: Reflections, pathways and unmaking Apartheid’s legacy.

From the book it is clear that UWC—as the university is more generally known—struggles with its roots. It has its origins in Apartheid’s grand plan as a separate university for coloureds. “The original planners of UWC in the late 1950s hoped that, hidden from view, it would offer no views of its own,” writes Lalu, a former UWC student and now professor of history who heads the Center for the Humanities Research on the campus.

UWC’s location is significant. It is situated on the outskirts of Cape Town, close to the airport and a series of impoverished coloured townships bordering an industrial area that’s hard to reach, even by public transport. That contrasts sharply with the surroundings of the two other major universities in the area, the University of Cape Town and Stellenbosch University, both well resourced and with roots in whites-only education.

Slurs abound for UWC: for example “Colouredstan” and “the bush”. These have been turned into badges of honor, UWC is still synonymous with “lack and burden,” though UWC’s national role in political, social and economic life is assured.

The editors have ambitious aims: to engage with the racial origins of the university and the “normalizing racial discourse” it bolstered. “Specifically,” they write, “we are interested in what it meant to overturn and disavow the apartheid foundations of the university and how, in challenging these precepts, the university may unfortunately have been rendered blind to the pitfalls of nationalism” (p.19).

Though the book never provides a chronology of UWC’s 50-year history, the outlines emerge clearly. These include its austere beginnings in Apartheid higher education; replicating the Calvinism of Afrikaner universities (students, mostly young men, were “required to wear ties and jackets”), repression of politics, and the fact that administrators, with few exceptions, were all Afrikaners. In the early 1970s, the pro-government university council would appoint the first “non-white” vice chancellor Richard van der Ross (in South Africa university presidents are known as vice chancellors). Van der Ross’s tenure also coincided with the radicalization of UWC student politics, followed by the rejection in 1982 by the new rector, Jakes Gerwel (in the photo above), of the “political-ideological grounds” on which UWC was established.

Later, in 1987, Gerwel would declare UWC “the intellectual home of the democratic Left” (Martin, p.27), as separate from the “liberal” white campuses (UCT, Rhodes, Wits University) and Afrikaner universities (like Stellenbosch) with their explicit ties to Apartheid. In the early 1990s, UWC became “the premier institution” (p.93) from whence the ANC prepared to govern.

The book carefully balances the fine line between celebration and critical distance. Poems (by among others the late Arthur Nortje) and photographs (both from the university’s own archive and a set commissioned from photographer Ingrid Masondo) complement chapters on space, architecture, personal recollections (by history professor Ciraj Rasool) and reflections on UWC’s academic legacy. More recent history appears with a discussion by Leslie Witz of controversy around an on-campus exhibition of photographs by Zanele Muholi documenting the black lesbian experience in South Africa; and Neil Myburgh’s chapter on the transformation of the dental faculty (UWC absorbed Stellenbosch’s dental school).

The book would suggest that the legacies of Van der Ross and Gerwel still need to be unpacked. Van der Ross—characterized briefly by Lalu as complicated, if mostly, negative; he attempted to “translate apartheid’s reason for separate education into a project of class mobility” (p.53)–later emerged as a member of parliament for a small white opposition party, while Gerwel has had a larger role. In fact, his public profile has overshadowed his equally impressive academic work, which includes his scholarship on Afrikaans cultural politics. Gerwel also played a central role in constructing the new postapartheid state. He went to work as chief of staff for the new president Nelson Mandela. Separately, he has worked to increase black people’s share in the economy, fronting, for example, a share scheme by an Afrikaner-owned multinational media company.

Early in the book, English professor Julia Martin captures UWC’s new challenge. She writes that UWC’s origins and development over the last 50 years “seems distant history” to the university’s current crop of students who face a new set of dilemmas. This generation of students wants “to talk about love and Palestine and the corporate branding of their clothes. About music, imagination, and the politics of food. About poverty, displacement, desire and education. About the internet, the spiritual quest, and the globalization of the mind.”

However, Martin finds that “for all their techno-cool, the present generation of students seem more tender than their predecessors were, less confident of victory.”

* This review was first published on Humanities Net.

German amnesia and Herero women

Over the weekend, Geoffrey York, the Africa correspondent for the Canadian Global and Mail (and apparently also the only correspondent for a major Canadian publication on the African continent) wrote, from Namibia, about the current Herero struggle for land, dignity, and reparations. The 1904–1908 German genocide against the Herero is considered by many to have been the first genocide of the twentieth century, as such it serves as the gateway to the Modern Age.

Over the weekend, Geoffrey York, the Africa correspondent for the Canadian Global and Mail (and apparently also the only correspondent for a major Canadian publication on the African continent) wrote, from Namibia, about the current Herero struggle for land, dignity, and reparations. The 1904–1908 German genocide against the Herero is considered by many to have been the first genocide of the twentieth century, as such it serves as the gateway to the Modern Age.

As York, accurately, describes the situation, nothing much has changed:

In the bush and scrub of central Namibia, the descendants of the surviving Herero live in squalid shacks and tiny plots of land. Next door, the descendants of German settlers still own vast properties of 20,000 hectares or more.

The Herero want their land back. They would prefer the State find a way, but if not, land invasions will do. That option is described as “a new kind of radicalism.”

York ends his article with an old kind of European, and North American, representation, that of the tired old African woman:

A Herero grandmother named Gendrede Kavari lives on a small dusty plot of land on the edge of Okakarara. Once she had a few animals, but she had no fence and they were stolen. Now she survives on a pension and a small income from collecting firewood. Some day, if she had a bit more land, she would like to have some goats. ‘We must get our land back,’ she says.

Gendredi Kavari was never meant to survive. Neither were her grandmothers and great grandmothers.

Germans butchered somewhere between 50 and 80% of the Herero population in a mere four years, and Herero women were special targets. Germany used a Herero uprising to justify the “streams of blood” program of annihilation. That uprising was partly inspired by Herero resentment at German sexual violence against Herero women.

In 1903, after 20 years of colonization, 712 European women lived among 3,970 European men in German South-West Africa. What to do? Rape. Although rape by German men of Herero and Nama women was common, prior to 1904 not a single case of a white man raping an African woman came before a German court. This became particularly acute in the attempted rape, and then murder, of Louisa Kamana.

Louisa Kamana was married to the son of Chief Zacharias. The two gave a ride to a German settler, who, that night, “made sexual advances” on Louisa Kamana. She refused. He killed her. The Court acquitted him. The case was appealed, and the settler was given three years in prison. Rape and murder of Herero women were common occurrences. The case only went to trial because a Chief’s family was involved, and no one among the Herero thought three years made up for a Herero woman’s life and dignity.

That’s the story of the genocide as well. Women and children were targeted. When the Herero were ‘allowed’ to escape into the Kalahari Desert, it was assumed most would die. It was also assumed more women and children would die. That assumption was correct. The German authorities explained that Herero women and children had to die because they carried dangerous diseases. Meanwhile, the German press shrieked that Herero women were ‘black amazons swinging clubs and castrating their foes’.

And so good riddance.

When concentration camps were established for the few survivors, one female-only camp was set up to ‘service’ the German troops. Sound familiar? As Herero leader Mburumba Kerina explained: “Hey, that’s my grandmother — a comfort woman.” In the other camps, along with sexual violence at the hands of settlers and troops, Herero women were forced to boil heads, often of their own family members, and then scrape off the flesh with shards of glass. Those skulls were then shipped off to museums and universities, as well as anthropological and private collections in Germany, providing decades of ‘scientific’ research as well as ‘entertainment.’

To date, only a few Herero remains have been returned, while the overwhelming majority remains in Germany.

Sexual violence was part of the colonization and subjugation process. From rape and murder to abduction and sex slavery to forced removal of women, German settlers and the German Empire had a special fate in store for Herero women.

So, when you read about the Herero grandmother named Gendrede Kavari who only wants a bit of land and perhaps some goats, remember the reparations not paid. Remember the debt never even acknowledged. It’s about more than a bit of land and perhaps some goats. It’s about time that debt was paid — with interest.

German amnesia and Herero Women

Over the weekend, Geoffrey York, the Africa correspondent for the Canadian Global and Mail (and apparently also the only correspondent for a major Canadian publication on the African continent) wrote, from Namibia, about the current Herero struggle for land, dignity, and reparations. The 1904–1908 German genocide against the Herero is considered by many to have been the first instance of formal genocidal. As the first genocide of the twentieth century, it serves as the gateway to the Modern Age.

Over the weekend, Geoffrey York, the Africa correspondent for the Canadian Global and Mail (and apparently also the only correspondent for a major Canadian publication on the African continent) wrote, from Namibia, about the current Herero struggle for land, dignity, and reparations. The 1904–1908 German genocide against the Herero is considered by many to have been the first instance of formal genocidal. As the first genocide of the twentieth century, it serves as the gateway to the Modern Age.

As York, accurately, describes the situation, nothing much has changed:

In the bush and scrub of central Namibia, the descendants of the surviving Herero live in squalid shacks and tiny plots of land. Next door, the descendants of German settlers still own vast properties of 20,000 hectares or more.

The Herero want their land back. They would prefer the State find a way, but if not, land invasions will do. That option is described as “a new kind of radicalism.”

York ends his article with an old kind of European, and North American, representation, that of the tired old African woman:

A Herero grandmother named Gendrede Kavari lives on a small dusty plot of land on the edge of Okakarara. Once she had a few animals, but she had no fence and they were stolen. Now she survives on a pension and a small income from collecting firewood. Some day, if she had a bit more land, she would like to have some goats. ‘We must get our land back,’ she says.

Gendredi Kavari was never meant to survive. Neither were her grandmothers and great grandmothers.

Germans butchered somewhere between 50 and 80% of the Herero population in a mere four years, and Herero women were special targets. Germany used a Herero uprising to justify the “streams of blood” program of annihilation. That uprising was partly inspired by Herero resentment at German sexual violence against Herero women.

In 1903, after 20 years of colonization, 712 European women lived among 3,970 European men in German South-West Africa. What to do? Rape. Although rape by German men of Herero and Nama women was common, prior to 1904 not a single case of a white man raping an African woman came before a German court. This became particularly acute in the attempted rape, and then murder, of Louisa Kamana.

Louisa Kamana was married to the son of Chief Zacharias. The two gave a ride to a German settler, who, that night, “made sexual advances” on Louisa Kamana. She refused. He killed her. The Court acquitted him. The case was appealed, and the settler was given three years in prison. Rape and murder of Herero women were common occurrences. The case only went to trial because a Chief’s family was involved, and no one among the Herero thought three years made up for a Herero woman’s life and dignity.

That’s the story of the genocide as well. Women and children were targeted. When the Herero were ‘allowed’ to escape into the Kalahari Desert, it was assumed most would die. It was also assumed more women and children would die. That assumption was correct. The German authorities explained that Herero women and children had to die because they carried dangerous diseases. Meanwhile, the German press shrieked that Herero women were ‘black amazons swinging clubs and castrating their foes’.

And so good riddance.

When concentration camps were established for the few survivors, one female-only camp was set up to ‘service’ the German troops. Sound familiar? As Herero leader Mburumba Kerina explained: “Hey, that’s my grandmother — a comfort woman.” In the other camps, along with sexual violence at the hands of settlers and troops, Herero women were forced to boil heads, often of their own family members, and then scrape off the flesh with shards of glass. Those skulls were then shipped off to museums and universities, as well as anthropological and private collections in Germany, providing decades of ‘scientific’ research as well as ‘entertainment.’

To date, only a few Herero remains have been returned, while the overwhelming majority remains in Germany.

Sexual violence was part of the colonization and subjugation process. From rape and murder to abduction and sex slavery to forced removal of women, German settlers and the German Empire had a special fate in store for Herero women.

So, when you read about the Herero grandmother named Gendrede Kavari who only wants a bit of land and perhaps some goats, remember the reparations not paid. Remember the debt never even acknowledged. It’s about more than a bit of land and perhaps some goats. It’s about time that debt was paid — with interest.

October 22, 2012

Running with white people

Two weeks ago, I was part of a 20 000 person strong crowd that participated in the Sophomore Nike Run Jozi. The first one was a 10km run (with an extra kilometer or so) through the Johannesburg CBD. From Braamfontein, through Troyeville, Yeoville and Hillbrow; the finish line was at Mary Fitzgerald Square in Newtown. We ran under a banner of reclamation and greatness. Armed with neon green tops and over-priced running shoes, we ran as corporate soldiers. Unified, running to “take back the city” and “reclaim our streets”.

Two weeks ago, I was part of a 20 000 person strong crowd that participated in the Sophomore Nike Run Jozi. The first one was a 10km run (with an extra kilometer or so) through the Johannesburg CBD. From Braamfontein, through Troyeville, Yeoville and Hillbrow; the finish line was at Mary Fitzgerald Square in Newtown. We ran under a banner of reclamation and greatness. Armed with neon green tops and over-priced running shoes, we ran as corporate soldiers. Unified, running to “take back the city” and “reclaim our streets”.

It’s unclear where the city went in the first place. No-one knows who stole it. And what of the streets? Did they always belong to us, these misplaced streets? This time around, we ran not under the dark shroud of night, but rather in the brutal, revealing light. We gathered on the bottom of Katherine Street in Sandton, shielding our eyes from the sun.

The route was to take us through Alex to Innesfree Park. 20 000 people; anxious, excitable and loud. Loud that is, until it was time for the national anthem to be sung. I imagined it was the nerves, the heat, the exhaustion but somehow, these factors miraculously disappeared in time for “Die Stem”. A thundering roar built up into crescendo, crashing like a wave over “In South Africa Our Land”. False start.

Alexandra Township lies just east of Sandton, separated from the Capital of Glam by two intersecting main roads. Proclaimed a “native township” in 1912, it was one of few urban areas in which black people could own land. In its 100 year history, the township has survived many demolition attempts. Its proximity to wealthy white suburbs made it a target for eradication. But it lived through the Group Areas Act, and breathed through the bulldozers. It came to a standstill in the Bus Boycotts and burnt in shame during the xenophobic attacks of 2008.

Alexandra is, for many, a place of pride. A nucleus for active resistance which housed many great leaders and writers. I know we’re not allowed to think this anymore. We’re no longer permitted to be in love with the township. We stand accused of romanticizing the unacceptable. Indicted for believing that some kind of culture breeds there. Do not make the hood look pretty. Do not portray it as if real people live there. If it’s not about poverty or violence, then it’s glossing over the facts and the hardships. Because apparently these things are mutually exclusive. You can’t be both hood and happy.

Running through Alex, known to its residents as Gomorrah, with a bunch of white people is an interesting experience. The previous day, 1 in 9 activists had been told to “go back to the townships” at Jhb Pride. A few minutes earlier at the starting line, a majority of the runners (who were white) refused to sing the beginning parts of the national anthem. I was feeling unsettled. Discouraged. Heavy under the weight of wealth and privilege.

It’s a lot to live with, let alone run for. On 18th avenue a burst pipe spews clean water onto the half-tarred road. “Oh my,” comments a blonde runner, “I can’t believe these people choose to live like this.” Another is concerned about the smell. “I’m going to struggle to get the stench of Alex off me when I get home.” You see, as much as this could have been a bridge built, for me it only highlighted the contrasts. That two communities a street apart can be so separate. South Africans have chosen ignorance. We have decided to not know what’s on the other side of the road. To be safe in our enclaves, and only venture out to edify our prejudices or prop up credentials.

October 21, 2012

President of France, King of Africa?

[image error]Why should it be a big deal if a French president gives a speech in Dakar? Lots of reasons. Rarely does anyone walk softly and carry a big stick in quite the same way that François Hollande did earlier this month. Hollande was walking softly—even talking softly—while in Dakar. Some five years after Nicolas Sarkozy’s infamous speech asserting that “the African man had not sufficiently entered into history,” Hollande seemed to be both pandering to and hectoring Senegal’s National Assembly in his address before it. Africa was the continent of the future, he insisted—young, with a growing economy, forward-looking. But Hollande also looked backwards, recognizing that Senegal had given a great deal to France in the past, whether voluntarily or not. Blaise Diagne took a seat in the French Parliament in 1914, he noted; Léopold Sedar Senghor helped to write a new French constitution in 1958. Democratic lessons keep coming—there are more women in parliament in Dakar than in Paris. The debt is deep, Hollande said, and it passes through the slave trade, recruitment into the world wars, the massacre of mutinying soldiers at Thiaroye in 1944, and so much else.

In New York for the UN General Assembly, Hollande’s diplomats had been waving the big stick. They pushed the Security Council to give conditional approval for a West African force to intervene in Mali. Hollande picked up that theme in Dakar, too. Tough to look like the new democrat when you are effectively arguing for an invasion—as necessary as that might be. Was this a new African policy or the old FrançAfrique?

Hollande was unequivocal about that. During his presidency, he said in an interview, “There will be France. There will be Africa. There won’t be any need to fuse the two words.” French-African relations would be transparent, he asserted, and characterized by respect.

Still, Hollande’s trip had a kind of look-at-the-birdie quality to it, and not just because of the saber-rattling in New York. The visit to Dakar was meant to serve as a counterpoint to his next stop, in Kinshasa, which Hollande clearly had mixed feelings about. The 14th francophone summit was being held there recently, but Congo’s President Joseph Kabila is not exactly the company that Hollande wants to keep, and Congo was not the first place on the continent he wanted to visit. Even while there, he went out of his way to express his discomfort with the “unacceptable” fashion in which Kabila governs the Congo, with the turbulent elections that kept him in power, and with the murky murder of human rights activist Floribert Chebeya in 2010. At Kinshasa’s French Institute, Hollande inaugurated a new A/V center named in honor of Chebeya, even as the investigation into his murder continues. He also met with opposition leaders and generally behaved… well, not exactly like an invited guest.

Another gesture—made the same week—was no less symbolic. Fifty-one years after French policemen murdered dozens, maybe hundreds, of protesting Algerians in the center of Paris on October 17, 1961, Hollande became the first French president to recognize that fact. Millions of tourists walk past the tiny plaque on the Seine that notes discreetly that here, from the bridges, policemen threw Algerians to drown. This is not some hidden place like, say, Philadelphia, Mississippi. But here, like there, the past isn’t dead; it isn’t even past yet. What the presidential confession means, no one knows yet. But if Hollande wants to talk colonial crimes, he’ll be a busy man.

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers