Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 517

October 19, 2012

Jazz Bonus Break

Uploaded in mid-August on YouTube, this 1968 clip may be the earliest known clip of Abdullah Ibrahim. In the video, a wiry (all arms and legs) Ibrahim is performing with his band at the time — consisting of John Tchicai, Gato Barbieri, Barre Phillips and Makaya Ntshoko — on German television:

If you haven’t had enough of Ibrahim, it was also his birthday last week Tuesday — we Storified an Abdullah Ibrahim Birthday Edition.

Tchicai, the tall, thin man playing saxophone on that 1968 live set in the video above died last week. Tchicai (Congolese father, who has an interesting story of his own, and a Danish mother) also collaborated with the South African bassist Johnny Dyani. RIP.

Here’s Tchicai performing in April this year (fast forward to the 6.23 mark):

Hugh Masekela performs a live version of Louis Armstrong’s “Rocking Chair” for The Guardian at Womad this past summer:

Drummer Tete Mbambisa, who doesn’t say much, has a new album. Buy it.

Now for the younger cohort. First up the Belgium-based, South African-born vocalist Tutu Poeane and her band:

Then Chicago’s Hypnotic Brass Ensemble.

From London, Soweto Kinch and Shabaka Hutchings:

French double bass Stéphane Kerecki talking about his new record:

Finally, though not strictly classified as jazz (but what is jazz?), check out this trailer for a new film about chaabi musicians from Algiers:

Read more here.

Kenya’s #purplezebra Spring

Political springs, as in social movements that topple and/or transform political regimes, occur when the youth of a nation get on the move. And that may be what happened in Nairobi this past Monday. A harbinger of spring.

Four hundred or so young women marched, shouted, hooted, danced, chanted, filled the streets of Nairobi. They carried a banner that read, “50% of all positions allocated to women should be reserved for women under 35 years. Give women an opportunity for fair representation through nomination rules of political parties.”

The women wore purple to symbolize their demands for fair and balanced appointments. They were a rolling democratic action. They were … a purple zebra. As Youth Agenda has explained, “Young women (Purple) in appointive and elective positions in political parties should appear as many times as the white on a zebra…#purplezebra”.

The #purplezebra emerges from many sources. The new, improved Constitution of Kenya (pdf) provides more rights and protections to women, children and youth, both defined as vulnerable citizens. In particular, the Bill of Rights of Kenya’s recently passed Constitution specifies the State’s responsibilities to women, children, youth, minorities and marginalized groups, and elders. The Constitution also mandates that no gender will have more than 2/3 of elected or appointed positions. This does not limit women to 1/3 but rather ensures that at least 1/3 of elected and appointed positions will be women. It’s a definite step forward, which of course relies on implementation.

The young women of Kenya have looked at the results thus far, and kept their eyes on the prize. In a country in which 70 percent of the population is 35 years or younger, age matters. Or at least it should. And Kenya is that country right now, and all predictions and projections suggest that it will continue to become younger and younger again.

This means, for women like Susan Kariuki, Chief Executive Officer of Youth Agenda, the group that brought the women who came from all political parties and structures together, the women in office must be from the 70%, the 35-and-under super majority. This means that restrictions, such as fees, must take into account the high levels of unemployment and underemployment of young women and address them accordingly. This means that the Parliamentarians as well as the appointed officials are on notice: don’t stand in the doorway, don’t block up the hall, there’s a purple zebra coming to do more than rattle your walls.

Canada likes Africa’s “new image”

Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper receives the Great Cross of the National Order of the Lion of Senegal from the hands of Senegal President Macky Sall (October 12, 2012).

After spending its first six years in power largely ignoring the continent, the Conservative Party of Canada has finally “discovered” Africa. Last week, Prime Minister Stephen Harper undertook a four-day trip to Senegal and the DRC—only his second trip to sub-Saharan Africa since taking office in 2006, and his first in five years.

Harper’s policies have (at least rhetorically) emphasized government belt tightening. Accordingly, the Conservatives have repeatedly cut Canada’s foreign aid commitments in order to focus on priorities such as lowering the budget deficit and buying $25 billion worth of fighter jets. Given their espoused economic policy focus, it is not surprising that the Conservatives sought to portray the Prime Minister’s recent trip as focused not on delivering foreign aid, but on promoting international trade.

The Canadian press largely embraced this narrative: “Africa no longer needs your help. It needs your investment,” read the first line of one article.

“These days Africa has a new image,” a Harper spokesman explained in a newspaper interview during the trip. “It has emerged as the region with the world’s second-highest growth rate … Wars and coups are declining, foreign investment is soaring, and democracy is expanding.”

Yes, it appears as though the “Africa rising” narrative has reached the halls of the Canadian Parliament.

This narrative was readily apparent in a speech given by Ed Fast, the Minister of International Trade, at a press conference following Harper’s trip. “There are more cell phones in Africa than India,” he noted, in announcing a 2013 trade mission to Ghana and Nigeria.

While Harper did announce an aid package during his visit to Dakar, he mostly focused on expanding the two countries’ trade relationship. A few days earlier, John Baird, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, had undertaken a similar trip to Lagos and Abuja, announcing—using a metaphor surely familiar to all Nigerians—that Canada would seek to increase its commercial ties with Nigeria because that was where the “puck” of the international economy was “going to be” in the future.

The other stop on Harper’s trip proved rather difficult to fit into the narrative of an emergent Africa ripe for Canadian investment: From Senegal, Harper traveled to the DRC to participate in the annual summit of La Francophonie. Harper used his speeches at the summit to rebuke the Congolese government, telling a gathering of opposition and civil society leaders, “We’re concerned about many things in the Democratic Republic of Congo, including … violations of human rights, difficulties, problems (and) unfairness in some of the electoral process.”

Again, the Canadian media were content to play along with this narrative. “Stephen Harper enters Africa’s heart of darkness,” read one headline.

The rhetoric surrounding the Prime Minister’s trip last week, then—both from government spokespeople and from the press—demonstrated a troubling bifurcation, a dividing of Africa into “good” and “bad” states. This portrayal, it should go without saying, is overly simplistic. The DRC has demonstrated strong economic growth and increased foreign investment, while Nigeria has struggled with sectarian violence and popular dissatisfaction with President Goodluck Jonathan’s policies. Neither of these facts is captured in a straightforward labeling of Nigeria as a “good” trade partner and the DRC as a “bad” human rights violator.

While it may not be politically wise to discuss Nigeria’s continued political problems at the same time as promoting increased trade with the country, or to encourage investment in the DRC while rebuking Joseph Kabila’s human rights record, one hopes that, behind closed doors, Canada’s policy toward Africa less resembles the simplistic media coverage of this past week than Prime Minister Harper’s public statements would seem to suggest.

* Nicholas Barber is a doctoral student in the Department of Anthropology at McGill University in Montreal. His research interests include representations of Africa and Africans in Western media, indigenous film and video. He has worked on development projects in Ghana and Lesotho and for the Film and Video Center of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in New York City.

October 18, 2012

10 African films to watch out for, N°7

I was surprised to find very few films by African directors in this year’s programme of the International Documentary Film Festival of Amsterdam. At my count, 4 out of 317 — Samoute Andrey Diarra’s Sand Fishers, Karima Zoubir’s Woman with a Camera, Nadine Cloete’s Miseducation and Muhammad Taymour’s One Minute — but maybe I have overlooked some. That said, if you’re in Amsterdam this week: another festival, Africa in The Picture, has a fair selection and kicks off tomorrow. AITP, not unlike that other Africa-focussed film festival in the Low Countries mentioned last week, had its subsidies cut this year — the Arts Council of Amsterdam who advised the city government on this is on record quoting “it is no longer needed” — so I’m happy to see its 15th edition organized despite the odds. Continuing our series here on the blog, below are 10 more films we’ll be looking out for.

From North to South (sort of):

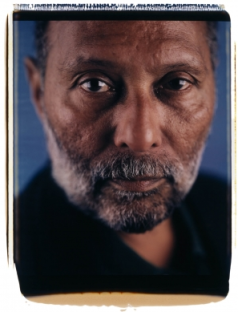

Accra-born, London-based John Akomfrah will turn his video installation The Unfinished Conversation on the life and work of academic Stuart Hall (photo above) into a film. Visitors to the Taipei and Liverpool Biennials were given a first glimpse of Akomfrah’s work, and reviews so far (here, here and here) have been promising.

One of the films showing at Africa in the Picture is Kenneth Aidoo’s first long feature Op de Grind (“On the grind”, filed under “Theme: Dutch Diaspora”). No English trailer yet:

Also tackling “diaspora” issues is Rengaine (“Refrain”). Rachid Djaïdani’s fiction film is set in Paris and tells the story of Dorcy (“a young Christian black man”) who wants to marry Sabrina (“a young arab girl,” according to the liner notes):

In A Minha Banda e EU, Inês Gonçalves and Kiluanje Liberdade share a story about “a new generation of Angolans — from Porto to Lisbon to Luanda — who see Semba and Kizomba as the greatest expression of their cultural identity”:

Afric Hotel is a documentary by Nabil Djedouani and Hassen Ferhani about South-North migration. A first fragment (“Jazz The Casbah”):

And here’s a second.

Shot mostly before the various uprisings in North Africa, Hala Alabdalla’s As if We Were Catching a Cobra originally set off as a film about political cartooning in Egypt (and Syria). It should make for insightful viewing. Here’s a longer rush:

Rui Simões’s film Kolá San Jon é Festa di Kau Berdi (2011) is now available on DVD. The film follows a group of Portuguese Cape Verdeans originally from Cova da Mora, Lisbon who travel to Cape Verde to attend the yearly São João Baptista festivities.

The Fade is Andy Mundy-Castle’s portrait of four barbers across the world. One of them is Offori “Tupac” Mensah who works in Labadi, Accra. Details.

In Maris de Nuit (“Night husbands”), French-Martinican writer Fabienne Kanor (who already has several other films about Martinique under her belt) travels between Martinique and Burkina Faso, portraying the phenomenon of the “dorlis” (jinns, spirits):

And for Espoir Voyage (“Voyage hope”) Michel K. Zongo followed the itinerary his brother and many other young Burkinabé migrants make to Côte d’Ivoire:

* Africa in the Picture runs until October 28. Also happening this week is the Festival de Cine Africano in Cordoba, Spain. And starting soon is the Kenya International Film Festival (in Nairobi, October 24-November 3).

#Kony2005

I didn’t pay much mind to the #Kony2012 kerfuffle when it first surfaced back in March. I couldn’t be bothered to watch the film and was a bit blasé about the re-emergence (as it seemed to me) of the Lord’s Resistance Army as a topic of wide international interest. But now Invisible Children has released another film that promises the unleashing of a new wave of activism (they’re promising to take over the US capital in mid-November) and awareness-raising. The new film is an ode to martyrdom (a frivolous aside: watch Ben Keesey from 20:02 onward and compare his embattled defense to this one) but I otherwise found no reason to add to the blogosphere’s thorough deconstruction of the phenomenon. Instead I went through my notes from a 2005 research travel through Acholiland. Over one month, I talked to representatives of the Ugandan Army and other organizations in Gulu, Kitgum and Pader. The conflict had been underway at that time for nearly 20 years already.

The research, which was intended to guide a planned documentary film, went in the end toward my own edification. My knowledge of the conflict, even if not necessarily my ability to make sense of it, increased. But the film that got made, “War Dance,” concentrated on an annual dance tournament held in Acholiland, and like #Kony2012 avoided delving into any political, economic and sociohistorical context.

Rather than explain why I left Northern Uganda without drawing hard conclusions on Kony, the LRA, and the popular support it enjoyed among Acholis, I’ve reproduced a small section here from the notes and photographs taken in 2005.

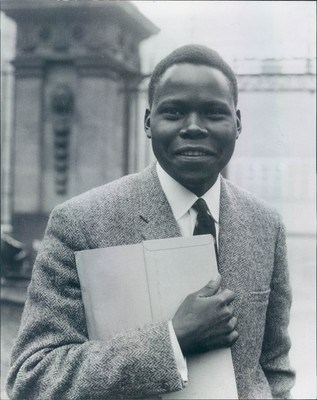

Kilama George (in the photo above) is slim and shy, introspective. He, like many of the young Acholis one meets in Acholiland, northern Uganda, shows no signs of trauma. Also like many young Acholis, Kilama George was abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army and spent time in the bush, fighting the Ugandan army and terrorizing civilians. In the bush, Kilama George was a bodyguard of Otti Vincent, the number two man in the LRA and a commander renowned for extreme viciousness, reputedly because of sexual impotence. Kilama George claims to have killed many people, merely carrying out orders, as he put it, and it was his ruthlessness on raids—torching huts, beating and maiming civilians—that brought him to the attention of Otti.

Kilama George is a particularly fascinating subject to interview for this reason: he is exceptionally thoughtful and perceptive about the LRA and its mystical leader. Unlike virtually all of my correspondents, George described Kony as having a mental problem, an assessment he made from seeing the LRA leader burst into sudden and inexplicable laughter. He also was able to explain that Kony’s frequent foretelling of government attacks was the result of maintaining regular radio contact with his commanders.

Kilama George’s story, and academic research currently being done in IDP camps increasingly affirms that simple readings of the LRA, its support among the Acholi populace and even the experience of abduction and return undergone by children are frequently wrong and with potentially harmful outcomes.

Many aid agencies have set up rehabilitation centres to provide psychosocial counseling to returnees. Much, if not all of this counseling is premised on the notion that time spent in the bush is essentially a continuous nightmare for the children, and that all children yearn to escape; only fear or death prevents some from actually doing so.

Most of the returnees I spoke to admitted that life in the bush was hard: in the dry season, water and food is particularly scarce and the lack of foliage cover means frequent attack by the Army’s helicopter gunships. Many, however, spoke of incidents that were startling, of unexpected kindnesses and actions that any casual follower or observer of the LRA would not expect.

George remembers being bound very tightly with rope by a commander at the time of his abduction, so tightly that he thought his arms might break. However, a few days later, his feet swollen to the point where he was unable to walk, the same commander carried George on his back, while other children similarly afflicted were summarily clubbed to death.

Alternatively, take the account of Anena Grace, a shy sixteen year old with a lovely smile. Grace walks with crutches as a result of being shot in the leg during her capture by the Ugandan Army. The leg is not healing properly and she has been in a rehabilitation center since February 2005 receiving medical attention and counseling. Further, Grace is seven months pregnant with the child of her “husband,” a rebel commander to whom she’d been given, and who died in the attack in which she was rescued. Grace was favoured over the commander’s five other “wives,” given the choicest foods, and never moving far from his side. In fact, when he was ordered to send his wives to Sudan for inspection by Kony, Grace alone remained with him. Grace attributes this treatment to her education, which meant that he relied on her heavily; both he and the other wives were illiterate.

As these stories reveal nuances in the experiences of abductees in the bush, so it must be that counseling and psychosocial care should not be automatically administered from a standpoint of presumed trauma. In fact, much of the discourse, whether economic, social or political about the war in Northern Uganda is reductive and facile, accepting as true and established ideas and conceits that are at best, only partly true and sometimes patently false.

The findings of Ben Mergelsberg, a young German researcher I interviewed who spent time in Northern Uganda, are striking if preliminary, and point toward the need for a more tailored approach to psychosocial care for returnees. Mergelsberg posits that newly abducted children are torn between two strong urges: growing in to the LRA and escaping out. These two essentially war with one another in the mind of the child, and typically cause tremendous stress, particularly in the initial period in the bush.

However, those children that survive what is essentially an initiation into a world with new rules and expectations experience an improvement in life and greater acceptance and trust, as they receive a gun and become full members of a community. Bullying by other more senior members tends to stop after a child becomes a soldier, and there is a sense of power attendant with wielding a weapon. The extent to which the urge to escape out persists determines whether a child soldier will actually attempt to do so, but it is far from certain that all abductees wish to escape. Many of Mergelsberg’s correspondents were able to enumerate advantages of life in the bush over life in the village, or still worse, the IDP camp.

A “wife” and son of Kony

Similarly, when a child does escape, it is the crossing once more of boundaries into a world, that of the wider Acholi community, with rules that are now unfamiliar and even incomprehensible after those of the bush. Further, between escape and rescue is a period of extreme peril, in which both the LRA and the government’s soldiers are potential enemies and represent equally the possibility of death. The trajectory of successful escapees—military barracks, reception centre, rehabilitation centre, home—is a bewildering series of transitions, accompanied by the loss of power and self-belief that comes with surrender of one’s gun, and the realization that one’s actions in the bush are likely to be perceived unfavourably by the wider community.

The experience of having lived in two worlds and retaining within oneself, perhaps permanently, the knowledge of both is the source of much difficulty for many returnees from the bush. While the war continues, both are options, although few seem to choose to return to the bush. There is however banditry in the region, often attributed to the LRA, that may be the work of returnees.

What is still more interesting is the claim by many former abductees that they remain soldiers. Perhaps this is acknowledgement that there is always a potential to react to an incident or situation by reverting to violence or drastic action. Perhaps it is acknowledgement of a skill acquired; many former LRA fighters join the 105th battalion of the Ugandan Army, a unit comprised entirely of those who once fought for Kony. Olum Michael, the commander that carried Kilama George on his back, is now a member of the 105, as it is known. The creation of the battalion last year has boosted the effectiveness of the army in countering LRA attacks.

Ex child combatants make radio appeals to those still in the bush

For Kilama George, and many others, the future seems uncertain, if not bleak. He walks several kilometers into Gulu from a nearby IDP camp to volunteer for the War Affected Children’s Association, a local NGO seeking to assist returnees. There is no money for further studies, partly because many livelihoods have been destroyed by life in the IDP camps, and partly because he did not do well in his O-level examinations, a fact that might be connected with having spent years of his life in the bush. While Kilama George is at times painfully eye shy, diffident and soft spoken, I cannot help but think that the past holds part of the key to his future. He has choices, both of which he understands, and knows, and who can say what frustration or desperation might impel him to choose.

October 17, 2012

Germany’s Turn

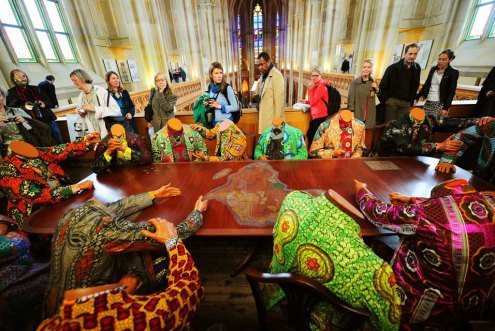

Yinka Shonibare’s installation ‘Scramble for Africa’ (Berlin, Germany, 2010)

If Ethiopian filmmaker Haile Gerima’s award winning film Teza (2009) is anything to go by, Germany’s relationship to art coming from African producers can be a helpful model. After fifteen years of trying to complete his film, he was finally able to release it worldwide with some help from German backers. Gerima rewrote parts of the script to take place in Germany, and independently casted and edited the film, keeping its integrity intact. Just a year earlier, a German university funded its first professorship in African Art. But what to make of Germany’s newest arts funding program for the African continent?

The German Federal Cultural Foundation (a government program) hopes to reinvigorate its relationship to the African continent through TURN, a 2 million euro art and culture initiative that will last through 2015. Wanting to build off the desire to have storehouses in Africa for pieces of cultural memory produced and preserved by Africans themselves, they created a new international program. Their goal, they say in a press release (pdf),

is to allow cultural institutions in Germany to gain knowledge about the art scenes in African countries, and by means of cooperative ventures between African and German artists and institutions, spark new impulses in the German cultural and artistic sector.

TURN in fact encourages German institutions to stage events involved in the program not only in Germany, but in Africa as well. Much like the American Fulbright scholarship, applicants must apply in conjunction with a German institution. However, unlike the Fulbright, the German institution assumes responsibility for ensuring that all funds are spent as contractually agreed upon. On the other hand, German institutions can also apply to do research projects in Africa, they need not jointly apply with local centers. Nor will the funds be distributed by said centers. This is in line with the initiative’s stated goal, though its fairness is questionable.

And who will determine the allocation of funds?

The three-person-jury is comprised of Sandro Lunin, a Swiss theater artistic director who has previously worked in Bamako and elsewhere, Nana Oforiatta Ayim, an art writer and the only jury member of African descent, and Jay Rutledge, a popular DJ and music journalist who has closely followed popular music in sub-Saharan Africa.

TURN’s biggest critic so far is Safia Dickersbach, the PR director of Artfacts.Net, an online art database located in Berlin. Dickersbach writes on her blog:

Does “TURN” really “revolutionize” the hegemonial treatment of the value and quality of African traditions and idiosyncrasies by the European art establishment which we have observed for too long? Will the time come when numerous diverse art scenes, creative communities and cultural circles on the African continent finally be taken seriously and treated as an equal, a partner that has an opinion – a voice that must be heard?

It’s great when funds can be made available to institutions and artists to progress their work, and the exposure it receives. Hopefully the integrity of the African artists and institutions involved can be maintained through what may be an unbalanced initiative.

“Our love is hot” for Nigerian pop singer Tiwa Savage’s new music video

Love is a theme used so regularly in many Nigerian pop songs. Many of them sound alike in the ears, and I’ve learnt not to expect too much. Yet, listening to and watching Tiwa Savage’s latest music video “Ife Wa Gbona” (translates: “Our love is hot”) has kept me murmuring: indeed love is a good thing. This song is a good reason to fall in love or want to.

From the opening scene where a car drives towards a house and a family is outside to receive a prospective groom and the surprise, cheers and hugs. Next: we see the groom sitting next to his bride-to-be in a room filled with relatives. Wedding preparation is being made. It is a convivial environment. The warmth is infectious even from watching the beginning of something good about to happen.

Then: Tiwa enters a room bearing a gift, and she is introduced, by a man we can assume to be her father, to a relative as “the little cousin” with “the best voice in town.” The surprise at how much she has grown, gives way to the couple offering her to sing at their engagement later that day. All this time, at the background, the song is playing under the conversations–and I’m still savouring the big difference in the setting from her other video when a final warning sounds from her father: “do not disgrace us.”

And does she disgrace?—Well, I have the song on repeat! (At last count—earlier today—the video has been seen by about 100,000 viewers on YouTube’s iRocking channel.)

The narrative of the video is as engrossing as the song, which blends pop with juju and highlife. It does well to bring up the warm feelings to the listener’s heart. Just as the title, this song is indeed hot: intense and bold. It is a reminder of many good things–mutual love, good wine, family, gathering warm feelings that rise to the throat.

The guitar that carries the song brings good memories of the twang in Victor Uwaifo’s Guitar Boy. And of course I have a feeling that it will the preferred wedding song at traditional weddings in Nigeria, as was Tosin Martin’s Olomi, Tuface African Queen, Sola Allyson’s Eji Owuro and not to forget Sunny Neji’s Oruka.

The scenes capture symbolic objects that translate affection: from play-acting lovers (Tiwa and featured artist Leo Wonder) crooning sweet-nothings to themselves in a coconut groove, camera pans to capture a hibiscus flower which blends with the choice of costumes–the buba and Iro Tiwa is wearing and the tye-dye of Leo Wonder, and when it translates to her sitting in front of a mirror, mulling over this “hot love” between herself and a lover. Her father dragging her off from loverboy and her unwillingness, all bring freshness to the narrative. The role-playing is all well put together. I also love the way her name—Tiwa—which translates to “our own” becomes a refrain for Leo Wonder. In it, I can capture the intent of innocence and natural love and desire.

Well, do I have to celebrate the agreeable tinge in Tiwa Savage’s voice, which retains that soothing feel, as this song offers her, an even better show of it. “Ife Wa Gbona” is apart, and it sets a different agenda for Tiwa Savage’s other singles like Love me 3x or Omo Ga.

Benin sculptor Gérard Quenum’s dolls never die

As the Beninese proverb rings out, ‘an old story does not open the ear as a new one does’. No illusions exist in here. If dolls never die, neither does their past. Much like the synthesised histories present in Gérard Quenum’s new sculptural works at the October Gallery, they will now, not die. Yet the gallery space simmers with an unsettling, murderous oppression and the stench of premature obituaries. These triumphant, looming figures demand a reactive first reading from the viewer, of haunting visions. They detain you by their presence, as they begin — from their distant glassy eyes, or defunct holes of the doll figureheads — to question you. Quenum’s aesthetic, his concentrated palette; a hue of black and a gamut of browns, with intricate punctuations of colour, mostly crimson red cloth produces a very particular kind of mausoleum.

Commanding the majority of the gallery floor is ‘Mort au dictateur. Vive la dictature!’ (Death to the Dictator, Long Live Dictatorship!). A rolling procession of child-like tanks composed from exhausted mortars, helmets and a singular doll’s head. Low in height and linear, the piece speaks in a muffle of the abhorrent history of dictatorship, but infers a more direct association with the recent fall of Gaddafi. There is a circularity at play, as Quenum describes: “a new leader is installed and the game begins again. So even though the dictator is dead, the insidious system of Dictatorship creates a new vision that’s exactly the same.” The sculpture gives birth to a layered concept of unerring disquiet. Creating a vast schism between such a vision of horror and its unchanging repetition, within the frame of an innocent childhood game, placing a child’s position in dialogue with their bounded imagination’s landscape and the adult reality.

Each of the plastic, mass-produced dolls heads; worn mortars, discarded beads, cloth, metal piping, shells and large recovered pieces of wood, have all been rescued by the artist. Before Quenum begins to assemble, he listens in to his objets trouvés. Explaining that he “can’t work with any object that’s brand-new or completely clean, since it wouldn’t contain that essential vibration which allows me to intuit things about which it’s trying to tell me.” He acts as a receptive, sensitive therapist, before he can start to resurrect, nourish and transform. Claiming that when putting them together “it’s as if another life begins.” But this is not a religious purification, or righteous resurrection; it is everything at once, with all its scars, blemishes, blisters and perversions intact, simultaneously.

Following from the artist’s excavation of each objects past, the pre-existent stories of his rescued dolls, his treatment of their heads varies. From a gentle positioning, leaving mud — and with it their history — to dry upon their faces, to scorching them with a blow torch, cauterising their skin and hair, a seemingly violent reclamation of their origin, from Western aid packages, sent away for their next life with African children. Eventually discarded, all stories and projections are still present. All of the freestanding sculptures that dominate Quenum’s new works are all composed of variegated wooden anatomy, with differing limbs and appendages. Quenum appears to favour the use of an absurdist scale, best represented in his piece (above) ‘En jouant les gros-bras’ (Flexing Muscle) in which a doll’s arm juts out, humorously in a ‘clenched fist’. A well-worn symbol of solidarity, unity and strength, next to a minute doll’s head on top of a towering torso.

Quenum becomes a ventriloquist. He allows the dolls to reveal and recite their own histories while projecting his intentions into them, all spoken complete, in his own distinct precise voice. With such a cacophony of embedded histories accommodated within each object that Quenum recovers from his urban landscape. That “might have served for decades as drums, mortars to grind food, or as pilings that supported the houses of peoples living on the lagoons around Porto-Novo,” in Benin. It is therefore dizzying — especially with the inclusion of the dolls’ heads — that once assembled, it doesn’t diffuse each pieces potency, silencing its ‘vibration’. But this serves as a testament to Quenum’s craft and plasticity as author. An overarching master of narration, with bravery and delicacy steers his collected histories towards his own semantic ends, safely.

Each figure presents a conflicting image of ourselves, not as infants, but the infant innocence and truths cloaked within a layered adult. Buried parts of ourselves that yearn for the comfort of truths, however feral, over illusions. These works unearth such a propensity, placing your innocence and vulnerability back on your skin. By the instigation of a reconciliation; that as we peer into the darker visions of life, the more cleansed we become because of it. Within Quenum’s challenging and bleak stage, he has amassed an apocalypse. But not a universal, widespread disaster or wasteland, barren. But from the original Greek translation, apocalypse, as a revelation of something hidden. Artefacts that victoriously proclaim — with fertility — the permanence of human endurance to outside agents. That society’s collective bad parenting and maltreatment cannot ever, completely ransack the spirit. That like well-formed thoughts, art transcending death, we never really die and neither do dolls.

Gérard Quenum’s exhibition runs until the 27th of October at the October Gallery in London.

Legson Kayira, the first Malawian novelist, has died

Malawi had three first novelists: David Rubadiri, Aubrey Kachingwe, and Legson Kayira, who has died this week in London aged 70. In the 1960s and 1970s Kayira wrote a number of works of fiction, but he will be remembered most of all for his 1965 memoir, I Will Try, an account of the astonishing journey he made after setting out on foot from his home village in the northern part of Malawi. He went first to Kampala, then to Khartoum, and finally to the United States, where he had won a scholarship to study at Skagit Valley College, Washington State.

All three of Malawi’s first novelists were exiled in short order following independence. President Kamuzu Banda based his popular legitimacy on reiterating ad nauseam a set of personal myths that sought to subsume the history of the new nation within his own biography, and there was simply no room for anyone who could write their own stories on a national level. Kayira’s memoir was especially problematic for the symmetries it contained with Banda’s own life. Both had been educated by Scottish missionaries at the prestigious Livingstonia Mission school and won scholarships to undertake further studies in the United States. Banda loved to recount how as a youth he had walked to the mines at Johannesburg (he had, but so had generations of other young men from the region). Kayira walked north rather than south, but he walked thousands of miles further, and at the end of his journey he wrote an autobiography that remained on the New York Times bestseller list for sixteen weeks.

The only surprise is that Kayira’s story, which imagines with great charm the Malawian subject’s coming-of-age/decolonisation as a single epic journey towards America, was never made into a Hollywood film.

Kayira sets off on his “walk to America” with copies of two books, the Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress, and a badge on his shirt which reads simply “I Will Try”. He understands his journey as a direct successor to those made by missionaries over the previous one hundred years:

Equipped with nothing better than sheer faith, faith in one’s self and one’s Creator, David Livingstone had tried and succeeded. Equipped with no greater tool than this same faith, Dr Robert Laws, the author of our motto, had tried amid unknown hazards and had succeeded [...]

The following excerpt is the opening to Chapter 7, “Legson’s Progress”, in which Kayira describes his first hours in Kampala.

On January 19 in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and sixty, I arrived in Kampala, a vast and impressive commercial city in the Protectorate of Uganda.

It was a fine morning. The sun had been in the sky for two or three hours, and the thermometers were rising. As soon as I had awakened that morning I had freed myself of the heat-infested cabin down in the basement of the steamer where we were sleeping and hurried up on the deck, where I had the pleasure of admiring the scene on the not far-off shore and enjoying the cool breeze of nature’s pure breath. The steamer anchored at Port Bell, only five miles away from downtown Kampala. My heart was throbbing with anxiety now, wondering whether or not I would be able to get into the city without any traveling documents. I stepped out, and slowly walked on what I thought to be the only pier, leading to the Customs Office. “Passes, passes,” I could hear men calling, as the mass of people in front of me slowly shuffled along the same pier. On the left side of the pier, two men were calling out: “Schoolboys, this way please.” This was my chance, really the only chance I had. I quietly joined a small group of boys and girls called “schoolboys”.

“Schoolboy,” one of the men would ask as each one came to pass through the line, and each one of us would nod in agreement.

I thus arrived in Uganda, my temporary destination, but America, my goal, was still far away, far away across land and ocean. I had told my friends at home that when I got to Uganda I would know what to do next, but now I did not know. I pulled out my map as soon as I was beyond sight of the suspecting Customs men. With my fingers I compared the distance I had covered and the distance still to be covered. I had come that far and there was no point in turning back now, I tried to console myself. At the same time I pitied myself for having plunged into such a journey. The motto on my shirt still said “I Will Try”, and I repeated the words as I had done now times without number: I Will Try. My shirt, however, was dirty, my shorts were dirty, and I was dirty. I would have to stay in Kampala longer than I had expected. I would try to get a job.

“Matoke (bananas) for sale here”, a young boy was calling a short distance away. Another one, standing not far from the other, was calling out, “Sugar canes for sale here.” I folded my map and after putting it back into the pocket went to the boy and bought a few bananas. Sitting down to eat my bananas, I pulled out my Pilgrim’s Progress and opened to my favorite page. “… and if you will go along with me, you shall fare as I myself, for there, where I go, is enough and to spare.”

October 16, 2012

‘Syn City’ Harare

Zimbabwe is a paradox. A country riddled with contradictions. While the often unpalatable and sometimes hair-raising stories are making news, the stories of everyday people of Zimbabwe are less reported, if not altogether the country’s best kept secret. “Generally, Africa seems to be portrayed in a negative light,” says Gerald Mugwenhi, better known as Synik, the four times nominee of the 2012 Zimbabwe Hip-Hop awards. “If people are showcasing the positive side they are usually the exception. Zim is like anywhere else, there are problems, yes, but there are also great things to talk about. However, the focus, when people hear of Zim, is the politics, but the people are a better story.”

Synik is a lyrically talented and much respected Hip-Hop and spoken word artist from Harare. He earned his initial stripes in the Zimbabwean Hip-Hop scene in 2008 when he released an EP which gained him the momentum to make contacts with other local artists. His debut album Syn City has been making some waves as a free download recently.

“The point of the free download was to make the music accessible to everyone. It is available to buy on all major online platforms but I wanted to give people who aren’t familiar with me or my music a chance to hear it as well. It made the album popular as many people got to talk about it, and to share it as well. I believe that sales would never have translated into much had we made it strictly for sale. A number of people got the free download and still bought it to show support, but for many people in Zimbabwe – and maybe some other parts of Africa – buying online is not a possibility.” The buzz that resulted from the album release had a lot to do with its accessibility. “I didn’t have any misgivings about the free download. I think it’s a good strategy for a debut album and the focus is more long term than immediate returns.”

Syn City, produced by Begotten Sun, is a result of a collaboration with many of Zimbabwe’s finest emcees such as Metaphysics, JnrBrown and Karizma to name a few. Out of mutual respect these artists got together with Synik to share their life experiences in Harare, so that the album could give a clearer reflection on their lives, and allowing for different voices to tell their stories. To Synik this album is a tribute to the city which helped shape him as an individual — particularly having left his job as an account assistant to pursue his music. The album offers a rare opportunity to get a glimpse into the capital city of one of the most demonised countries of today through the lenses of articulate young people, giving a broader understanding of what is really going on. One could argue that it gives an account of life in Zimbabwe that is not of the newspaper variety. These artists — cue Chuck D — are the news anchors of the streets of Harare.

“I live in Harare, which I dubbed Syn City playing on my moniker and loosely borrowing the art from the movie,” Synik explains, “but the stories in the album are not unique to Harare. Syn City can be any city.” The film he is speaking of is Sin City, and its visuals are also referred to in the video for the title track which is said to be the first 3D music video from the African continent:

“Syn City was shot on a green screen, the backplates are photos we took around the city. The wide angle of the city is a photo we took which was then built into something resembling a 3D environment. By so doing we were able to control the separate elements and achieve the Sin City feel were going for.”

The video, produced by Nqobizitha Mlilo and Rufaro Dhliwayo, has been released online but is not intended to be limited to the online market only. So far it has not yet enjoyed airplay on Zimbabwean television or regional music channels. However, Synik is determined to have it shared on as many platforms as possible.

The album is a mixture of various sounds including the mbira combined with the occasional use of his mother tongue Shona to give it a Zimbabwean feel.

“I think a true reflection of my communication is the balance between my mother tongue and English. There are ideas one can express easier in one language and not the other, so using both gets the message out truthfully.”

The album is self-explanatory. Synik is being brutally honest in his account of life in general and his life in specific, not even shying away from showing his vulnerable side. The track ‘Muripo’ is the one song he says was made at his most vulnerable, expressing his emotions quite freely. It is a deeply personal album. The original album had 12 tracks, but soon after its release a bonus track ‘Marching as One’, originally just an interlude, was added.

“Marching as One is a rebellious song,” Synik says, “so on the album it was good for transitioning into the AfrICan joint. We later on did the full version of ‘Marching’ for the [urban art] Shoko Festival special edition of the album.”

Apart from music, Shoko Festival seeks to incorporate many other art forms such as photography, comedy and dance. It also has a strong element of skills-sharing through workshops and discussions to bring about social change. One of the themes discussed this year was freedom of expression.

Since the Zimbabwean government introduced tough media laws in 2002, freedom of expression has been under attack, and it is interesting to see what the role of artists has become.

“There is a joke here,” Synik laughs, “you may have freedom of expression but no one guarantees you freedom after expression.” He points out that fear may have been used as a political tool so much that paranoia has become a by-product. “Hip-Hop as a radical and outspoken art form is the perfect tool in cultural activism.” That doesn’t mean, he adds, that one would automatically have to become the ‘voice of the voiceless’. “There are artists, who speak boldly, but personally I am not an outright political individual.” But in the same breath he admits that the line between the personal and the political is thin — especially in a place like Zimbabwe.

“I’ve never really felt motivated to be a voice because of the conditions around me. I just express what I’m feeling at the time. I try to bring about positive change through my music. Whether it’s through introspective music, where I try to deal with myself from the inside, or through asking bigger questions about what’s going on around. I just believe artists have a great opportunity to hold up a mirror to society so it can change if it needs to. It takes a certain amount of bravery to speak against some things.”

Although Synik is gradually getting recognition for being a Hip-Hop artist, he also has performed as a spoken word artist and still supports the poetry events happening in Harare. To him, Hip-Hop and poetry are very much interrelated. Synik continues to grow in his musical expression and has recently incorporated the acoustic guitar to his performances. He considers himself to be one who is still trying to find himself.

There is no denying that Zimbabwe is experiencing tough times. Popular western media have been almost relentless in their reporting about the calamities it is facing. Amid all the chaos, human rights violations and economic turmoil, in meeting Synik, a different kind of story is unearthed. A story of a young and driven individual who is determined to realise his dreams, making it despite all the portrayed doom and gloom. Media is only telling one story, so it’s only right that Synik tells another one. His story is told from his — and possibly many other urban Zimbabweans’ — perspective. Just because not everything is a dream doesn’t mean that everything is a nightmare. Home is home and the place Synik calls home is Harare; Syn City is a shout-out to this place.

* Amkelwa Mbekeni is one half of the Planet Earth Planet Rap International Hip-Hop segment of And You Don’t Stop! radio show on WBAI (New York).

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers