Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 513

November 8, 2012

How to write about children in Africa

In early October this year, PBS released the documentary ‘Half the Sky’, based on the book by frequent AIAC target and New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof and his wife Sheryl WuDunn (a former Times journalist) focusing on the lot of girls and women in the Global South. As part of Kristof’s mission to replace their oppression by opportunity, he visits a number of sites. The action usually revolves around Kristof accompanied by a famous American actress. The first stop had to be in Africa, of course. Kristof visits Sierra Leone where he, along with actress Eva Mendes, takes on the case of a 14-year old girl Fulamatu, who has been raped repeatedly by a next door neighbor, passing as a “pastor.” Kristof and Mendes visit the shelter where the girl was taken by her mother. Over the next few minutes, Kristof proceeds to do his own police work, and takes it upon himself to arrest the rapist. He also counsels the young girl. By the end of the segment however, it is unclear whether the rapist will stay in prison and pay for the crime and whether Fulamatu will be safe (her father throws Fulamatu and her mother out of the house because of the “shame” and attention they bring to the family). The whole ends with an odd scene, with Mendes — who looks as she does not want to be there — saying goodbye to Fulamatu, offering her a necklace and hugging her: “You are so beautiful, brave and strong.” Kristof then moves on to Thailand and Mendes goes back to the US.

In early October this year, PBS released the documentary ‘Half the Sky’, based on the book by frequent AIAC target and New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof and his wife Sheryl WuDunn (a former Times journalist) focusing on the lot of girls and women in the Global South. As part of Kristof’s mission to replace their oppression by opportunity, he visits a number of sites. The action usually revolves around Kristof accompanied by a famous American actress. The first stop had to be in Africa, of course. Kristof visits Sierra Leone where he, along with actress Eva Mendes, takes on the case of a 14-year old girl Fulamatu, who has been raped repeatedly by a next door neighbor, passing as a “pastor.” Kristof and Mendes visit the shelter where the girl was taken by her mother. Over the next few minutes, Kristof proceeds to do his own police work, and takes it upon himself to arrest the rapist. He also counsels the young girl. By the end of the segment however, it is unclear whether the rapist will stay in prison and pay for the crime and whether Fulamatu will be safe (her father throws Fulamatu and her mother out of the house because of the “shame” and attention they bring to the family). The whole ends with an odd scene, with Mendes — who looks as she does not want to be there — saying goodbye to Fulamatu, offering her a necklace and hugging her: “You are so beautiful, brave and strong.” Kristof then moves on to Thailand and Mendes goes back to the US.

Kristof has drawn criticism for his storytelling techniques, his tendency to exoticize cultures, his parachute style of engagement, his disregard for the impact of structural forces and power dynamics and ill-suited solutions. But Kristof is not the first and will certainly not be the last Western reporter who, in his conscientising endeavors, locates himself central to the stories of vulnerable children. Neither will he be the last one to steer his parachute towards Africa.

The category “African children” occupies a rather distinct, almost symbolic position in Western media. Stories about African children as victims of hunger, malnutrition, disease and violence attract quite some attention, compassion, aid and increasingly hands-on ‘help’ from visitors from wealthier Western countries. Interest in the lives of these young people and awareness of the challenges they face is important, not lastly because there are so many of them. Around 50% of sub-Saharan Africans are under 25 years old. They’re also Africa’s “future.” They’ll be running the continent at some point. (As we know this is also becoming a cliché and platitude pulled out at every conference or press conference by self-serving politicians and those undermining public education.) A second reason why these young Africans deserve a spotlight is that they carry the brunt of today’s developmental problems. When it comes to hunger, malaria, malnutrition and poverty, it’s often the children who are most vulnerable. Reporting on the challenges this group faces and thinking of ways to protect and empower them is therefore essential to meaningful development initiatives.

Yet the ways in which the media frame and report their lives reveal some fundamental shortcomings that directly relate to the particular position that African children occupy in the collective Western imagination. Here, the child has turned into a ‘type’; a type with a typical and singular story of despair and helplessness. This story started in 1968 with photos of child victims of the Biafran secessionist war and was passionately taken to the global stage by Band Aid’s 1984 ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas’ campaign which effectively drew global attention and compassion to the victims of the Ethiopian famine. Photographs of perishing children with flies on their faces and desperate stares into the cameras shocked the world, pulling in millions of dollars. The overwhelming momentum of the campaign and its usage of the pictures seem to have set a trend. Having proved their shock — and some would say sensational value — African youth came to serve as the ultimate illustration of disaster and hopelessness.

Thirty years after Band Aid’s Campaign, ideas around the typical ‘African child’ as the ultimate victim of drought, famine, poverty and disease have firmly taken root in the Western imagination. Today, the “remember the children in Africa” guilt-trip seems as effective in pushing obstinate European kids to finish their supper as it was during the campaign.

Similarly, much of disaster reporting (and NGO funding appeals) on Africa have made use of the African child’s compelling victimhood; from nature, disease and geography casualties to mutilation and abduction targets. To argue that these child victims don’t exist or shouldn’t get outside support would be senseless. As real as the Ethiopian famine was in the 1980s, as real are the devastating effects of malaria, HIV/AIDS, famine, wars and displacement today. The problems are real, the children are real and many are in need of real support. The problem, however, is that the ‘African child’ has become a rather static and one dimensional symbol; a symbol that renders all children in Africa into unclothed, dirty, muddy and powerless creatures. It obscures the wide diversity in children and renders those that do not suffer ‘the African way’ invisible.

Like Kristof’s documentary, CNN’s report on ‘The Life of an African Child’ (which aired earlier this summer), is also a case in point. In the report, CNN quantifies the story and presents it as statistics. There is an obvious attraction in telling stories by numbers. Not only is it clear and space efficient, this type of numerical message is more likely to stick with readers. Yet the power of simplicity goes hand in hand with the defect of falsehood. The danger is that in the process of convenient simplifying, a plethora of fictional tales will trump the facts.

Like Kristof’s documentary, CNN’s report on ‘The Life of an African Child’ (which aired earlier this summer), is also a case in point. In the report, CNN quantifies the story and presents it as statistics. There is an obvious attraction in telling stories by numbers. Not only is it clear and space efficient, this type of numerical message is more likely to stick with readers. Yet the power of simplicity goes hand in hand with the defect of falsehood. The danger is that in the process of convenient simplifying, a plethora of fictional tales will trump the facts.

CNN, for example, tells us that “In Sub-Saharan Africa, 34% of children under five are sleeping under an insecticide-treated mosquito net.” Being close to a third, the 34% is easy to remember. And since even the most couch bound Icelander won’t struggle to grasp the concept of a mosquito net, for those with an interest in African children it’s a story that sticks. But since this figure doesn’t tell us anything about the percentage of children who actually need the net or how this number relates to, say, the situation 5 or 10 years ago, it is bound to spell (out) a whole lot of fiction about its young subjects. Should the reader be alarmed by the implication that two-thirds of Africa’s under 5 year olds are still waiting for their nets? Or should we be delighted that, given the (hypothetical) fact that, say, 70% of all Sub Saharan African under 5 year olds actually need a net and that “34%” represents an increase of — I don’t know — 200% compared to a decade ago, we’re halfway toward a happy ending? Crying for context, the straightforward number smudges the facts.

Nevertheless, the report provides a useful and clear oversight of major themes and challenges that youth in Africa face. Contrary to much news on the subcontinent, the report does not fail to uncover the subcontinental variety. To give another example, it contrasts Burundi’s percentage of underweight under 5 year olds (39%) with Swaziland’s (6%), and juxtaposes the primary school teacher per pupil ratio in the Seychelles (1:22) against the Central African Republic’s (1:95). Moreover, it steers clear from the popular disaster focus and expresses some solid optimism. The report tells us that today, the number of African children dying before the age of five has decreased with almost 50% over the past four decades. Especially in the current context of relatively high rates of GDP growth in various countries such as Rwanda, Ethiopia as well as Tanzania on the one hand, and hopeful democratic improvements on the other, some cautious cheering would therefore not seem out of place. Isn’t it rather baffling, then, that the report’s single visual illustration shows us an apparently dirt-poor girl, clothed in rags, carrying a muddy torn bottle?

Not really; CNN shows the African child that Western audiences came to ‘know’ and expect (ever since Biafra and Ethiopia). The type of child we are used to think and speak for; the ‘voiceless other’ whose imagined life is captured in tables and graphs and whose priorities and solutions we feel capable to define. With half of Africa’s population under 25, it might be about time to pass the microphone to them and listen to what they have to say.

Children’s Radio Foundation (CRF), a Cape Town based non-profit organization, chose to confront the problem by doing exactly that: offering youth not only the microphones, but equipping them with both the media skills and tools that encourage them to think and question critically, vent their concerns, share their stories, advocate their ideas and connect with their peers (in their own languages). Being central to their communities’ developments, young people have stories to tell and relevant opinions to express. What many don’t have is the infrastructure to air and share these ideas.

Children’s Radio Foundation (CRF), a Cape Town based non-profit organization, chose to confront the problem by doing exactly that: offering youth not only the microphones, but equipping them with both the media skills and tools that encourage them to think and question critically, vent their concerns, share their stories, advocate their ideas and connect with their peers (in their own languages). Being central to their communities’ developments, young people have stories to tell and relevant opinions to express. What many don’t have is the infrastructure to air and share these ideas.

Making use of the continent’s most widespread and penetrative medium — in 2011, over 90% of African households had access to a radio yet only 6.2% of the population logged on to the internet — CRF has been working with local radio stations in Rwanda, Liberia, South Africa, the DRC, Tanzania, Zambia and Ethiopia since 2006. By training voluntary facilitators at community radio stations in producing youth driven radio shows (and providing them with appropriate program curricula), they create sustainable platforms for youth dialogue. Across South Africa alone, CRF works with 12 different community radio stations (from Atlantis to Aliwal North to Moutse) where youth report every week on problems such as alcohol abuse, gang activity or xenophobia and add their voice to debates around issues such as polygamy, corporal punishment and gender equity. Nationwide, SA FM airs ‘The Radio Workshop’, which offers youth a mix of current affairs and infotainment every Saturday at noon.

In Tanzania, one of the partner stations is Radio Sauti (which reaches 5 million listeners). Here young Tanzanians have shared their experiences of, for example, how their parents’ conflicts affect them and the meaning of their country’s Constitution. In a broadcast (and audio slide show) from Arusha, streetchildren speak about their daily routines and interactions on the streets. More Westwards, in the DRC, the Congolese broadcaster RTNC made room for the youth show Yoka Biso, where youth explore challenges like educational inequality. Today, Children’s Radio Foundation-trained youth reporters are producing radio shows from 50 different project sites. Far from displaying voiceless victims, the radio shows are a testament to children’s capacity to be agents for change and to confront critical community issues themselves. Far from being misrepresented in some graph or video, youth attempt to reclaim their own stories.

With the Arch’s blessings:

Children’s Radio Foundation productions are accessible worldwide through their website, Facebook page and podcasts on SoundCloud. Photos by Lerato Maduna. More photos here.

10 films to watch out for, N°10

Here’s another random selection of ten films to watch (some of them already doing the rounds, others still in production). In no particular order: Lomi Shita (Abraham Gezahagne’s “The Scent of Lemon”), is “set in 1972, in a season of hot political turmoil that started the downfall of the [Ethiopian] Emperor and the mass executions of top officials.” Cast: Elisabeth Melaku, Moges Chekol and Solomon Tesfaye. Ethiotube has the trailer. ‘Lomi Shita’ is screening at the Ethiopian Colours of the Nile film festival this week (Addis Ababa, November 7 – 11). Also showing at the Addis festival is Hisab, a short animation film by Ezra Wube. ‘Hisab’ is a humorous take on the hustle and bustle of Addis Ababa, and has the best opening lines. For those of us not in Ethiopia, the film’s available on YouTube:

Here’s another random selection of ten films to watch (some of them already doing the rounds, others still in production). In no particular order: Lomi Shita (Abraham Gezahagne’s “The Scent of Lemon”), is “set in 1972, in a season of hot political turmoil that started the downfall of the [Ethiopian] Emperor and the mass executions of top officials.” Cast: Elisabeth Melaku, Moges Chekol and Solomon Tesfaye. Ethiotube has the trailer. ‘Lomi Shita’ is screening at the Ethiopian Colours of the Nile film festival this week (Addis Ababa, November 7 – 11). Also showing at the Addis festival is Hisab, a short animation film by Ezra Wube. ‘Hisab’ is a humorous take on the hustle and bustle of Addis Ababa, and has the best opening lines. For those of us not in Ethiopia, the film’s available on YouTube:

Mkhobbi fi Kobba (Fr. “Soubresauts”; Eng. [ballet term] “Sudden Leaps”) is a short film by Leyla Bouzid (who is the daughter of director Nouri Bouzid), exploring a mother-daughter relationship in a Tunisian “petit bourgeois” milieu. The film’s sound score was composed by oud player Anouar Brahem. A fragment (while waiting for an official trailer):

Le Sac de Farine (“The Bag of Flour”), is a film by Kadija Leclere about a young Moroccan girl kidnapped from a Belgian orphanage — where she was placed by her father — and forcibly returned to Morocco — by her father:

Some outtakes from Music and War Stories, a film the SoundThread team made with South Sudanese musicians in the wake of the country’s independence:

The trailer for Sea Pavillion, a short by Marysia Makowska and Todd Somodevilla, recorded in Macassar (a former South African “coloured beach” which sits in between Khayelitsha and Somerset West), featuring South African actors Stefan de Clerk and Colleen van Rensburg. We’ll have to watch it to understand the South Africa connection:

Trailer/teaser for For Those Whose God is Dead, a film directed by Jeremiah L. Mosese (born in Leribe, Lesotho):

And three films that have no trailers yet:

Laan (“Leaf”) is a short film by actress Lula Ali Ismaïl (Djibouti/Canada), also her directing debut, tackling khat abuse in Djibouti. Here’s an interview with the director (in French) about her recording of the film in Djibouti and the obstacles she had to overcome while there — financial troubles, mostly.

Laan (“Leaf”) is a short film by actress Lula Ali Ismaïl (Djibouti/Canada), also her directing debut, tackling khat abuse in Djibouti. Here’s an interview with the director (in French) about her recording of the film in Djibouti and the obstacles she had to overcome while there — financial troubles, mostly. Kenyan Hawa Essuman’s film project Djin, chronicling the clash between a coastal village’s old mythologies and new developments, received a €25,000 prize for the film’s production at the African Film Festival of Cordoba in Spain recently. Details on the film’s website.

Kenyan Hawa Essuman’s film project Djin, chronicling the clash between a coastal village’s old mythologies and new developments, received a €25,000 prize for the film’s production at the African Film Festival of Cordoba in Spain recently. Details on the film’s website. And Le Rite, la Folle et Moi (“The ritual, the crazy woman, and I”) is Togolese Gentille Assih Menguizani’s second film about Togolese rituals. Her first film, Itchombi, spoke about male initiation. In her new film she documents ‘Akpéma’ — a ritual ceremony in the Kabyé region during which elderly women teach young girls how to become “dignified and mature” women.

And Le Rite, la Folle et Moi (“The ritual, the crazy woman, and I”) is Togolese Gentille Assih Menguizani’s second film about Togolese rituals. Her first film, Itchombi, spoke about male initiation. In her new film she documents ‘Akpéma’ — a ritual ceremony in the Kabyé region during which elderly women teach young girls how to become “dignified and mature” women.

(This week’s list of 10 included, we’ve arrived at 100 new films to watch. Recap: 1-10, 11-20, 21-30, 31-40, 41-50, 51-60, 61-70, 71-80, 81-90, 91-100. More next week.)

November 7, 2012

Tendai Maraire (of Shabazz Palaces) breaks down new mixtape

Tendai Maraire (Photo @ Ben Irwin)

“This is an African Hip-Hop movement.” Seattle-based Zimbabwean Tendai Maraire aka Fly guy Dai (one half of Shabazz Palaces duo) sounds adamant. And he has the digital mixtape to prove it. On ‘Pungwe’, Maraire “not so much brings African music to hip-hop, but rather strips back the facade of modern hip-hop to show the African roots that were always there” (according to the press release). Wanting to know more, and already warmed up to the demo by Chief Boima’s mixtape of the mixtape, we asked him to break down the tape track by track. Play it while you read Maraire’s notes. First, the cover of the mixtape:

A Toast to Frame and Ro.

I wanted to start the Digital Demo with the mbira instrument to lay the foundation musically that this is an African Hip-Hop movement. So I left it in there raw. In ghettos all over we all have friends that you grow up with that you wish would excel in their talents more. But before they’re even legally old enough to pay taxes or enlist, they’re forced to make life-changing decisions that never give them a fair chance to contribute their gifts to the world. Before twenty-one, they’re making six figures selling the product they were born addicted to. At twenty-five they catch a case and they have no chance to earn a decent living. At twenty-five, they learn how lucrative, crooked and deadly it is. By that time, it’s too late. Plus, you figure out who is behind that business. You feel the same as them. I’m just trying to get what I can based upon the hand I was dealt.

Boom.

I remember when Zimbabwe gained independence. My mother had a big party at the house in Seattle — with all her friends, Zimbabwean and American. My uncle, who fought in the guerrilla war against the white Rhodesian state, flew in weeks later. She started celebrating every year and even would get together with friends to sponsor groups from Zimbabwe to come and perform. Years later she focused more on performing, and non-Zimbabweans took over. They called it a Marimba festival and later transitioned it to Zimfest, which still exists. One year, my brothers and I went when my father was still alive living in Zimbabwe. After we came back, we saw that it had not represented our culture, history or the people indigenous to Zimbabwe. So we started flipping tables etcetera. The festival was stopped and dialogue started on how things needed to change. I promised that day to everyone that I would change it. See, Zimbabwean music has a rich story-telling history. Some songs have messages that are inappropriate for those of European descent to sing. But yet they still feel comfortable doing so even though Shona people feel this way. So ‘Boom’ is me throwing my first punch at those that still disrespect the music. While I touch on some subjects that personally affect me when they do it. Boom!

WhatUlukn@.

I am no stranger to illegal activity that affects our people in America. When I first came back to America, a kid named Serge and I where known as the African Booty Scratchers. I didn’t understand why people who looked like me were laughing at me. Even the ones that knew me before I left. I always felt that America saw us the same; not as African-American, Zimbabwean or even Black. Just Ignorant Negroes. As I got older my friends and I learned we’re all in the same social and economic positions. But I still had American friends who thought I felt better than them because I was Zimbabwean. And friends that were from Zimbabwe who thought I was better than them or lost my culture because I had a curl and wore Jordans. Then of course there was the police that I knew were crooked but never had a reason that they knew of to fuck with me. With this song, this is me just saying: why are you looking at me when I have shit to deal with too?

I Execute My Confidence.

When DJ Boima finished his blends on the mixtape, it had ‘Pitche Mi’ by Youssou N’Dour on it. I wanted to rap over it. I called Ish — and this is what came out.

We Need To Talk.

This track is about scenarios and conversations or arguments I went through with different women in the past while doing music. I’ve had several conversations about women with other artists and just wanted to express these thoughts. It’s really tough for an aspiring artist to work without a financial outcome from that work. Like Jean-Michel Basquiat kicking it with Andy Warhol. It usually never works out. But it did for me.

FU.

I think this speaks for itself.

How This All Started/Boy Wonder.

I just wanted talk a little bit about my story from a child to becoming a young adult. Writing helps me to deal with issues I don’t want to speak to people about. Then I grow up and mature from those matters I touched. Sometimes…

Like That…

Of course male black culture is always exploited as negative. As if there are no hard working brothas that are living a good life with their wife. They love to go to the club, hear black music and spend money celebrating who they are. I’m just expressing to black women that they should be proud of whom we are no matter the situation. Times are rough everywhere. So just let your man know you love him. Let him be him. He’s black and beautiful. Just like you.

Quarterblack.

For years the NFL quarterback has been looked at as the premier athlete in American sports. He gets the big deal, women and power to do what he wants when he wants. It took years for blacks to be a normal part of the draft discussion. I’ll never forget when Charlie Ward won the Heisman and led in almost every statistical category there was that year. He led Florida State to a national championship. This is just in honor of the black quarterbacks doing their thing today and how far they have come. Especially Mike Vick.

It’s Time For You To Go.

In 1994 our family visited Zimbabwe for the first time with our mother. At the time Biggie was just hitting the scene. We were driving down the street bumping ‘Juicy’. I remember we pulled up to a pick-up truck that had some uniformed workers in it. A white man was driving. Now imagine a mini van with young black kids — hats to the right, Gucci glasses — screaming in deep Biggie voices: it was all a dream! The workers looked at us like “shhhh.. Not good.” The white guy mugged but straightened up when we mugged back. Young Maraire Boys being crazy at home. I hung out the window and said “hay man if you don’t like it you can leave.” Days later we went to Victoria Falls by train. We were at the statue of Cecil Rhodes there. I remember talking to a white African guy who asked where we were from (he knew our American accents). I said Seattle. I asked him where he was from. He said, “We used to live in Zimbabwe and moved out to South Africa, we just stopped here before we go to our new home.” Now he was heading to Atlanta with his family. He was basically saying goodbye to Africa as a whole, moving to a whole new world of white culture.

It’s Alright.

Sometimes I write because I had a good day. Then I’m talking to a friend and they aren’t doing well. So I write their scenarios down and blend them all together. This time I just wanted to say everything is going to be all right.

Things you don’t know about African Women

‘Queen Amina’ (Photo @ Kelechi Amadi-Obi)

Starting two years ago, the Thomson Reuters Foundation launched TrustLaw, “a global hub for free legal assistance and news and information on good governance and women’s rights.” One of the major parts of TrustLaw is TrustLaw Women. Monday’s TrustLaw Women ran, as its major piece, a curious squib under the headline, “Five things you didn’t know about women’s status in ‘traditional’ Africa.” I know. The heart sinks at “you”, sinks further at “didn’t know”, and then plunges to unfathomable depths at the invocation of “‘traditional’ Africa.” And while some will exclaim that the square quotes around ‘traditional’ suggest irony, that’s not enough.

The five “things” are elderly women peacemakers and negotiators; women rulers and heads of states; women warriors and soldiers (“including Queen Amina”); women legislators and adjudicators of both State and Market; and, finally, independent women who had access to easy and cheap divorce.

The article’s author Alex Whiting mentions, in passing, that colonialism and Christianity opposed these various forms of women’s formal autonomy and power.

It would be too easy to lambast the piece for its ‘traditional’ Western National Geographic golly-gee tone, especially in the absence of any news hook for the piece, other than to inform ‘us’, ‘you’, that African women did stuff … once. And some still do.

But there’s something else going on, a missed opportunity. Whiting relies on four sources for her ‘things’: UNESCO documents from 2003, another one from 2005; an on-line ‘historical museum’; and a scholarly journal article from 1972. Scholars, analysts, activists, artists and just plain folk have been sharing this information for decades. But apparently only with one another.

So, thanks to Alex Whiting for pointing out the silence and the noise concerning “women in ‘traditional’ Africa.” What the TrustLaw article misses, however, is the action agenda of its own sources. Almost each piece Whiting references argues, urgently, that the structures of women’s power are not ephemera we can only see in the mists of some African Brigadoon. Women have struggled to preserve and adapt those structures. They are here, now. Not knowing that ‘thing’ is not due to a lack of resources, but rather to a political economy of violent exclusion.

For example, in one of the pieces, the authors Kimani Njogu and Elizabeth Orchardson-Mazrui ask, “Can culture contribute to women’s empowerment?” Their answer is yes. While their immediate focus is the Great Lakes region, their point is broader. Sustainable development and ‘progress’ can only occur as part of “working through communities instead of against them.” “‘Traditional’ African women” are not bereft of either knowledge or power. Their empowerment cannot begin by denying them their history, including their very present forms of power and knowledge.

That’s not about ‘traditional’ women, and it’s not about ‘modern’ women. That’s about ‘you’ and the “things you don’t know.”

November 6, 2012

#Elections2012

Americans vote today–or more to the point it is the “most important election in the world” decided really by a select group of American voters living in what is known as “swing states” and by something called an electoral college. If you’re wondering: no the popular vote doesn’t matter; only afterwards and purely for the legitimacy claims of whoever wins tonight. American elections are infamous for their shenanigans (especially by Republicans; remember Florida 2000 and watch Ohio and Florida closely tonight). Outside election monitors are barely allowed. And as for foreign policy–drones, renditions, etcetera and for all the bluster from the GOP about Benghazi (where’s that?)–it doesn’t matter. America’s political class (including Obama) believe they have a purpose to save the world, remember. That said, some people still don’t even know who the candidates are. Let’s hope they’re not Americans voters. As for us, some of us can vote, others can’t (we’re immigrants). But we’ll occasionally dip in on Twitter with good humor, music and snark. So while the networks fill dead air till about 10pm or so (basically they won’t have anything substantive to add until the results come in), here’s some classic “presidential” moments from the world of cinema, music and sports.

“The 40th President of the United States,” Richard Pryor:

And since some Americans (including well educated ones) still can’t get their head around the idea of a black president, what better thing to do than watch movies that celebrate that fact. This summer, “Film Comment” published an essay on all those films with black presidents in them. From the essay: Starting with the problematic “Rufus Jones for President” (1933, with a mammy-like Ethel Waters and a young Sammy Davis Jnr) to James Earl James in The Man (1972). The latter’s plotline is just short of absurd: Earl Jones becomes President after the incumbent is killed when a roof falls in at a German conference and the vice president suffers a stroke (dramatic yes). Then the 1990s brought us Tiny Lister as president (yes, Deebo from “Friday”) in “The Fifth Element” (1997), Morgan Freeman gave another speech in “Deep Impact” (1998), long before he played Mandela; and Ernie Hudson looks bulky and serious in “Stealth Fighter” (1999). In the 2000s, Chris Rock pretended to be president in “Head of State” (2003), Dennis Haysbert and DB Woodside played the president on TV (“24″), Lou Gossett Jnr was a Christian fundamentalist president (think George W Bush) who converts in “Left Behind” and then takes charge in “Solar Attack” (this is a franchise for Evangelicals). Terry Crews hamming it up in “Idiocracy” and Danny Glover (!) played the President in “2012.” Finally, there’s “The Avengers” (2012) in which Samuel L Jackson plays a kind of Obama. The “Film Comment” essay includes this line, which may apply to Obama:

In the dream life [i.e. Hollywood], a black man becomes America’s president only once civilization is doomed or life as we know it has come to an end.

That said, the last word goes to The G.O.A.T. Muhammed Ali interviewed on the British TV talk show, “Parkinson’s”back in 1971. Ali responds to a question about whether he would like to be President of the United States.

#ThisisElections

Americans vote today–or more to the point it is the “most important election in the world” decided really by a select group of American voters living in what is known as “swing states” and by something called an electoral college. If you’re wondering: no the popular vote doesn’t matter; only afterwards and purely for the legitimacy claims of whoever wins tonight. American elections are infamous for their shenanigans (especially by Republicans; remember Florida 2000 and watch Ohio and Florida closely tonight). Outside election monitors are barely allowed. And as for foreign policy–drones, renditions, etcetera and for all the bluster from the GOP about Benghazi (where’s that?)–it doesn’t count. That said, some people still don’t even know who the candidates are. Let’s hope they’re not Americans voters. As for us, some of us can vote, others can’t (we’re immigrants). But we’ll occasionally dip in on Twitter under the hashtag #ThisisElections with good humor, music and snark. Till then, some classic “presidential” moments from the world of cinema, music and sports. First some humor:

“The 40th President of the United States,” Richard Pryor:

And since some Americans (including well educated ones) still can’t get their head around the idea of a black president, what better thing to do than watch movies that celebrate that fact. This summer, “Film Comment” published an essay on all those films with black presidents in them. From the essay: Starting with the problematic “Rufus Jones for President” (1933, with a mammy-like Ethel Waters and a young Sammy Davis Jnr) to James Earl James in The Man (1972). The latter’s plotline is just short of absurd: Earl Jones becomes President after the incumbent is killed when a roof falls in at a German conference and the vice president suffers a stroke (dramatic yes). Then the 1990s brought us Tiny Lister as president (yes, Deebo from “Friday”) in “The Fifth Element” (1997), Morgan Freeman gave another speech in “Deep Impact” (1998), long before he played Mandela; and Ernie Hudson looks bulky and serious in “Stealth Fighter” (1999). In the 2000s, Chris Rock pretended to be president in “Head of State” (2003), Dennis Haysbert and DB Woodside played the president on TV (“24″), Lou Gossett Jnr was a Christian fundamentalist president (think George W Bush) who converts in “Left Behind” and then takes charge in “Solar Attack” (this is a franchise for Evangelicals). Terry Crews hamming it up in “Idiocracy” and Danny Glover (!) played the President in “2012.” Finally, there’s “The Avengers” (2012) in which Samuel L Jackson plays a kind of Obama. The “Film Comment” essay includes this line, which may apply to Obama:

In the dream life [i.e. Hollywood], a black man becomes America’s president only once civilization is doomed or life as we know it has come to an end.

That said, the last word goes to The G.O.A.T. Muhammed Ali interviewed on the British TV talk show, “Parkinson’s”back in 1971. Ali responds to a question about whether he would like to be President of the United States.

November 5, 2012

80% of Angolans alive today have only ever called one man President

Eighty percent of Angolans today have only ever called one man President. Sure, some have had other allegiances; there was a serious armed opposition and there were 27 years of civil war, but José Eduardo dos Santos has remained the head of state for 33 years. His party hasn’t lost power since the anti-colonial war was won in 1975. But following impossible uprisings in Tunisia and elsewhere, talk of regime change in Angola has grown more serious.

Eighty percent of Angolans today have only ever called one man President. Sure, some have had other allegiances; there was a serious armed opposition and there were 27 years of civil war, but José Eduardo dos Santos has remained the head of state for 33 years. His party hasn’t lost power since the anti-colonial war was won in 1975. But following impossible uprisings in Tunisia and elsewhere, talk of regime change in Angola has grown more serious.

When underground rappers emerged as key players in a burst of anti-government protests in 2011, Al Jazeera went to investigate. Their film, Birth of a Movement, asks: “Can young activists inspired by Angola’s underground rap scene take on a political elite that has ruled for decades?” It is an important question, which only raises more questions — what constitutes the long-ruling political elite? Outside of dos Santos and his family (and who is family? already more questions), who has the power to influence business as usual in the Angolan parliament? Perhaps this is asking too much of a 25-minute documentary.

Birth of a Movement is ultimately a portrait of three prominent activists: Carbono Casimiro, Mbanza Hamza, and especially Luaty Beirao, as they struggle to take on MPLA’s propaganda networks through popular media outlets.

Cameras show the work of allies at a radio stations holding roundtable discussions on how to assert civil rights. They also follow the taxi-to-taxi distribution of political rap albums. Just a few years ago public criticism of the regime was rare; now it’s been played inside the most public form of transportation in the city. Filmmaker and journalist at Al Jazeera, Ana de Sousa puts these actions in context:

Though hard for others less familiar with Angola’s history to understand, the very fact of 17 people attempting to hold a protest felt like a huge change. And as the year progressed and the protests grew, it just got more interesting.

…widespread fear of a return to war, and the distant memory of a political massacre several decades ago, had successfully stifled the spirit of public protest among those old enough to remember those events.

Later, the journalist’s bleak footage of a bloodied, ransacked room gives another indication of the state’s brutal crackdown on protestors, and public space. In the face of this violence Carbono, Mbanza, Luaty, and other activists featured in this film show tremendous strength and courage. The journalists and film crew documenting their efforts also have our respect.

But Birth of a Movement is also up against the constraints of the show it was made for — Al Jazeera’s Activate promises a focused, resolving narrative in under a half hour.

But Birth of a Movement is also up against the constraints of the show it was made for — Al Jazeera’s Activate promises a focused, resolving narrative in under a half hour.

The show has this own rhythm, and stories are fit into their general format. First, the audience is introduced to prominent activists filmed in the middle of direct community action. Key facts about the history of their fight and the current situation are provided in a text bar on the right simultaneously. This opening sequence helps give each episode a sense of urgency and the excitement of breaking news. Once we know a little bit about the larger movement, we learn more about the individual activist’s decision to fight. We hear most from well-educated secular young men who frame their fight in terms of rights (appealing either to civil rights or human rights vis-à-vis group identity), while messier historic alliances are put aside.

So, watching the documentary, we see fantastic shots of hundreds of people marching on the streets carrying the colors of UNITA, but there is no discussion of the long and complicated history of this political party, turned rebel army, turned political party.

In the lead up to the August elections, journalists in the country raised concerns about increased violent attacks carried out by both MPLA and UNITA supporters in the strategically important, symbolic provinces of Huambo and Benguela. Maka Angola’s António Capalandanda and Rafael Marques wrote that the lack of media coverage and dialogue at a societal level points to greater distrust between citizens and a climate of fear in front of the August 31st elections and its results.

Two months on, UNITA has continued to dispute the results of the August election through official channels. But not much is being said about efforts to acknowledge past violence. Christopher Pycroft puts this violence in some perspective:

Two months on, UNITA has continued to dispute the results of the August election through official channels. But not much is being said about efforts to acknowledge past violence. Christopher Pycroft puts this violence in some perspective:

During 1993, UNITA laid siege to pockets of government control in the central Angolan towns of Cuito, Menongue, Malanje, and Luena, seeking to divide Angola in two. Despite a partially effective unilateral UNITA cease-fire, announced in September1993, which enabled humanitarian aid agencies to bring relief to some of the 3 million people who were faced with imminent starvation, the situation in Angola remained critical. At least 2 million people were forced from their homes because of the war.

Can young activists work through the painful associations of their parents and grandparents?

And what about their music? We hear rap playing in the background of many scenes, but there is less discussion of who and how this music inspires. How do they see their work in relation to the larger body of important music styles in Angola, and to their political histories? Can they make truly popular music without being co-opted by commercial interests closer to dos Santos? We have seen for example, a complicated story of international investment in Kuduro. (Marissa Moorman has considered brand Kuduro on this blog.) Maybe we see a little more when Luaty goes to help his friend make a music video.

So we’re back to these questions: what constitutes the long-ruling political elite? Outside of dos Santos and his family, who has the power to influence business as usual in the Angolan parliament?

So we’re back to these questions: what constitutes the long-ruling political elite? Outside of dos Santos and his family, who has the power to influence business as usual in the Angolan parliament?

See for example, these ministers of the church and party:

“MPLA Fomenta Seitas Religiosas” [Source]

From the Catholic Church’s pre-election endorsement of the MPLA, to reports of certain Pentecostal churches announcing the presence of the SINSE (the state intelligence agency) to ensure members vote MPLA, to SINSE’s recent attacks on Father Pio Wakussngafor his efforts to fight housing demolitions and the forced relocation of poor and vulnerable communities, we can’t ignore the campaigns carried out under powerful church media networks. But given their own complicated histories with the MPLA the target of anti-government protest movement keeps moving.What is clear is that the political fight is wherever people gather.

Angola: Birth of a Movement airs on Al Jazeera at the following times GMT: Monday, November 5: 2230; Tuesday: 0930; Wednesday: 0330; Thursday: 1630; Friday: 2230; Saturday: 0930; Sunday: 0330; Monday: 1630.

November 4, 2012

Weekend Bonus Music Break

“Halleluja.” Ghanaian-Swiss OY breaks down hair politics over some church loop. Next: Ghanaian-Canadian singer-songwriter Kae Sun’s ‘Ship and The Globe’, the debut single off his forthcoming LP “Afriyie”:

Chicago has its very own Shrine. Yasiin Bey + Hypnotic Brass Ensemble = Fela Kuti’s ‘Water No Get Enemy’ (H/T Okayafrica):

Shot in Arusha, Tanzania: Joh Makini and Dunga’s ‘Sijuti’:

From Senegal, a new video for Pape & Cheikh’s ‘Lonkotina’:

Sudan-born multi-instrumentalist Ahmed Gallab aka Sinkane (he has worked with groups like Yeasayer and Caribou; I blogged about him a long time ago). Is this first video off his new record “Mars” a Steve Miller tribute?

From Soweto, The Federation’s smart self-marketing halfway through their new video:

South Africans Spoek Mathambo, Okmalumkoolkat and braSolomon get the Ravi Govender-video-remix-treatment — CUSS TV-style:

This was the second of two Spoek music videos released in the space of a week. Here’s the second, earlier one:

Copenhagen-based duo Okapii say they’re trying to explore West African vibes “and other nice things” in ‘Don’t Mind the Rain’. Kinda see what they’re getting at. No video yet:

…not unlike Brussels-based Débruit (we’ve mentioned him before) who released another far-out but quite beautiful video to go with one of his tracks off “From the Horizon”–no prizes for recognising the samples:

* Tom did some of the bookmarking of music videos for this week.

November 2, 2012

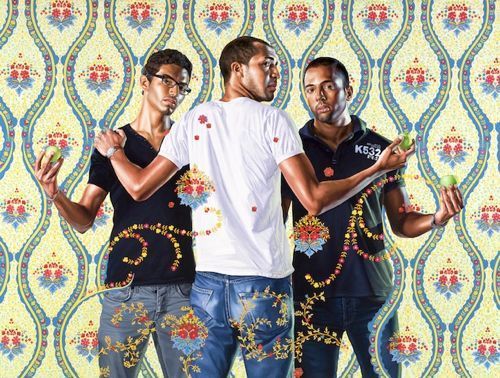

Kehinde Wiley Goes To Paris

Perhaps it is simply through good timing that I am rereading Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark and lingering over one sentence: the subject of the dream is the dreamer. Such it is with artist Kehinde Wiley’s continued complex relationships with the Black body.

Wiley’s “World Stage” series has come to Paris. This time, he attempts to tackle Françafrique by exhibiting work featuring locally sourced male models from various former African colonies and then provocatively bringing the portraits back to France. The portraits are beautiful, colorfully rich and in some cases through the background, clearly situated in the model’s culture of origin. He wants to “turn France on its head.”

Yet, to the French press’s delight, the assumed position of power in Wiley’s work is, as always, European.

The urban magazine, A Nous Paris, described Wiley’s as “wild castings from around the world,” and that “with [Wiley], the B-Boys have the allure of majesty and the painter, Titian, could get out of the ghetto.” Most importantly, they note, in Wiley’s portraits we have the “codes” of hip-hop, uncouth culture as they suggest in this context recognized through baggy jeans and sneakers, and the “codes” of the assumed art greats, recognized through symbolic stances and gestures.

Wiley himself has openly stated that often in his work, models were fabricated and the clothing was invented through artistic liberties. However, this exhibition features a superb video accompaniment featuring many of the young men posing in the pieces. What becomes apparent quickly is how relaxed Wiley was amongst the youth of North Africa. For him, these possible revolutionaries have ruffled the shackles of a former oppressor and stand basking in a culture rich and all their own. Except that they must assume the pose of the former.

Like critics have pointed out before, Wiley seems either reluctant or unwilling to do anything but skim the surface of the societal issues aroused through his work. The aesthetics of the cultures he encounters are dismissed, as in Israel, or leaving the work almost always un-localized.

It becomes even more problematic as Wiley recounts his traverse into what he endearingly calls “Black Africa”. As he ventures deep into the dark, he recounts how he encounters people in Gabon who seem to cling heavily onto the cultural legacy the French left behind. None of that was discussed for the Arab former colonies, but no matter. He goes further, wondering, what must it be like for these Black Africans to be encountering a Black American?

And so it goes. From Congo Brazzaville, where he says he is arrested for taking pictures during an election season, and onto Cameroon. Black Africa is lumped together, and the dreamer becomes the subject of his projection. Wiley himself is the son of a Nigerian father. Raised by his African-American mother in California, he met his father in a dramatic fashion when he was 20. So too was the landscape he encountered. How to approach Nigeria? Perhaps by othering it.

Wiley had almost intimately discussed Morocco and Tunisia as the separate entities that they are. But not so for Black Africa. Instead of questioning what it must have been like for Arab youth to be encountered by a gay, Black American, he questions only “Black Africa”.

The mosaics and market found fabrics featured in the work featuring North Africans is superimposed with the power notions of European derived artistic invention. The portraits featuring sub-Saharan Africans are triple imposed. Dutch wax fabrics, the same to be found from Ghana down to Cameroon, lace over the young men in front of them. Unlike the Arab youth, these West Africans clutch tools.

A broom, a rod. What to do with the hands of men who you feel to hold no power at all, even as they continue to fight for recognized cultural progression against an assumed background of French dominance? How do you read the French inclusion, and now American reading, of their space? They can be read simplistically as weapons. Or they can be read as a final gasp of frustration from one not knowing how to read an unknown place of origin.

* Kehinde Wiley’s The World Stage : France, 1880 – 1960 is on view at Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris, October 27 > December 24 2012.

Kehinde Wiley Comes To Paris

Perhaps it is simply through good timing that I am rereading Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark and lingering over one sentence: the subject of the dream is the dreamer. Such it is with artist Kehinde Wiley’s continued complex relationships with the Black body.

Wiley’s “World Stage” series has come to Paris. This time, he attempts to tackle Françafrique by exhibiting work featuring locally sourced male models from various former African colonies and then provocatively bringing the portraits back to France. The portraits are beautiful, colorfully rich and in some cases through the background, clearly situated in the model’s culture of origin. He wants to “turn France on its head.”

Yet, to the French press’s delight, the assumed position of power in Wiley’s work is, as always, European.

The urban magazine, A Nous Paris, described Wiley’s as “wild castings from around the world,” and that “with [Wiley], the B-Boys have the allure of majesty and the painter, Titian, could get out of the ghetto.” Most importantly, they note, in Wiley’s portraits we have the “codes” of hip-hop, uncouth culture as they suggest in this context recognized through baggy jeans and sneakers, and the “codes” of the assumed art greats, recognized through symbolic stances and gestures.

Wiley himself has openly stated that often in his work, models were fabricated and the clothing was invented through artistic liberties. However, this exhibition features a superb video accompaniment featuring many of the young men posing in the pieces. What becomes apparent quickly is how relaxed Wiley was amongst the youth of North Africa. For him, these possible revolutionaries have ruffled the shackles of a former oppressor and stand basking in a culture rich and all their own. Except that they must assume the pose of the former.

Like critics have pointed out before, Wiley seems either reluctant or unwilling to do anything but skim the surface of the societal issues aroused through his work. The aesthetics of the cultures he encounters are dismissed, as in Israel, or leaving the work almost always un-localized.

It becomes even more problematic as Wiley recounts his traverse into what he endearingly calls “Black Africa”. As he ventures deep into the dark, he recounts how he encounters people in Gabon who seem to cling heavily onto the cultural legacy the French left behind. None of that was discussed for the Arab former colonies, but no matter. He goes further, wondering, what must it be like for these Black Africans to be encountering a Black American?

And so it goes. From Congo Brazzaville, where he says he is arrested for taking pictures during an election season, and onto Cameroon. Black Africa is lumped together, and the dreamer becomes the subject of his projection. Wiley himself is the son of a Nigerian father. Raised by his African-American mother in California, he met his father in a dramatic fashion when he was 20. So too was the landscape he encountered. How to approach Nigeria? Perhaps by othering it.

Wiley had almost intimately discussed Morocco and Tunisia as the separate entities that they are. But not so for Black Africa. Instead of questioning what it must have been like for Arab youth to be encountered by a gay, Black American, he questions only “Black Africa”.

The mosaics and market found fabrics featured in the work featuring North Africans is superimposed with the power notions of European derived artistic invention. The portraits featuring sub-Saharan Africans are triple imposed. Dutch wax fabrics, the same to be found from Ghana down to Cameroon, lace over the young men in front of them. Unlike the Arab youth, these West Africans clutch tools.

A broom, a rod. What to do with the hands of men who you feel to hold no power at all, even as they continue to fight for recognized cultural progression against an assumed background of French dominance? How do you read the French inclusion, and now American reading, of their space? They can be read simplistically as weapons. Or they can be read as a final gasp of frustration from one not knowing how to read an unknown place of origin.

* Kehinde Wiley’s The World Stage : France, 1880 – 1960 is on view at Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris, October 27 > December 24 2012.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers