Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 511

November 23, 2012

Friday Bonus Music Break

We should start numbering these bonus music breaks. First up, above, from Kenya: the Large Gang, who claim to be “a lifestyle,” or at least more than a music group. Also from Nairobi (H/T “urban soul” blog GetMziki), the Grandpa Records family (basically a group of artists that are signed to the label) doesn’t take itself too seriously. Refreshing:

Coupé-décalé from Côte d’Ivoire in front of a green screen with beats by DJ Arafat (check the hilarious virtual guitar halfway into the video):

A new and dreamy video for Ghanaian singer Efya:

You’re familiar with Mensa by now, so you know what to expect. File under Good Music (seriously) / Humor / No Further Comment:

According to South African rapper Jack Parow, Afrikaans (the language) is Dead.

But that’s of course not quite what he means, if you listen closely to the lyrics. Another Afrikaans rapper, also from Cape Town, is HemelBesem. Not sure what’s up with the Tennessee reference at the start here:

Switching gears: South London rapper Corynne Elliott aka Speech Debelle’s living for the message:

I’ve been listening to Salif Keita’s excellent new record this week. It’s produced by Philippe Cohen Solal (from Argentinian Gotan Project). Here they talk a bit about the recording (also introducing Esperanza Spalding) — the recurring song in the background is stand-out track ‘C’est Bon, C’est Bon’, a collaboration with Roots Manuva:

And finally, Seu Jorge has uploaded to his YouTube channel the complete concert he gave a year ago at the Quinta Da Boa Vista park in Rio de Janeiro at the occasion of the Dia da Consciência Negra. It was a star-studded affair (what a band!). Here’s Seu Jorge jamming with Caetano Veloso:

Killing an African Warlord

“Key & Peele” (Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele) are considered the next generation of top black comedians (that’s a link to The New York Times endorsement). Their show on the American channel Comedy Central is supposed to take over from where Dave Chappelle left things when he went on vacation to Durban, South Africa. They’ve received the endorsement of Barack Obama (they’ve done sketches about Obama’s “anger translator” Luther). In mainstream newspaper profiles they’re described as not treating “social issues with kid gloves,” “send(ing) up race, class and culture while holding the attention of a young, diverse demographic” and skewering black and white characters alike. Not everyone agrees. On Salon.com, Karina Richardson writes that “Key and Peele address (the) tension and frustration (in how the world sees black people and how black people see themselves) by juxtaposing black identities, their own and their characters’, with black caricatures in popular culture.” However, she claims, “the show’s largest flaw is its preoccupation with translating a particular black experience for liberal white sensibilities. Its eagerness to avoid offense hangs over every tepid sketch about race, sketches already laboring under excessive gentleness and lack of imagination. In each sketch black people are impeded by their own blackness, or more specifically black men cling to an idea of black masculinity, one that Key and Peele suggest is a needless performance.” Anyway, they’ve just scored a second season where they do sketches like the one above. Not sure I find this sketch–with its bad accents–funny (my post from a while ago refers). But maybe that’s the point?

New South Africa, Old Stories

In the “new South Africa … miracles leave us exactly where we began.” So says John, Julie’s servant, in Yael Farber’s play, Mies Julie, playing at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn, suggesting that little has changed in South Africa since the end of apartheid despite its promises of freedom and equality. If John didn’t point out that the play takes place eighteen years since apartheid’s end, and if Strindberg’s original setting of the play on Midsummer Night hadn’t become South Africa’s Freedom Day in Farber’s rendition, you could easily mistake the play for being set during apartheid. And this is obviously Farber’s point. Perhaps this is why Benjamin Brantley in The New York Times thinks that the play “speaks boldly about that nation today.” But its recent success in Edinburgh and now in New York where its run has been extended, probably tells us more about the way that audiences in the Global North like to think about South Africa than it does about the actual dynamics of the place today.

In the “new South Africa … miracles leave us exactly where we began.” So says John, Julie’s servant, in Yael Farber’s play, Mies Julie, playing at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn, suggesting that little has changed in South Africa since the end of apartheid despite its promises of freedom and equality. If John didn’t point out that the play takes place eighteen years since apartheid’s end, and if Strindberg’s original setting of the play on Midsummer Night hadn’t become South Africa’s Freedom Day in Farber’s rendition, you could easily mistake the play for being set during apartheid. And this is obviously Farber’s point. Perhaps this is why Benjamin Brantley in The New York Times thinks that the play “speaks boldly about that nation today.” But its recent success in Edinburgh and now in New York where its run has been extended, probably tells us more about the way that audiences in the Global North like to think about South Africa than it does about the actual dynamics of the place today.

What does white America do when there is no longer a place with worse race relations than the United States? Convince themselves that there still is, of course. The conclusions about interracial desire that the play draws allow audience members to shake their heads when they leave the play: How terrible it is in South Africa! What a shame nothing came of Mandela’s great promise! The irony, of course, in this election year, is palpable.

If you take the play as an example of current South African theater and literature more generally, you might think that nothing has changed there either. J.M. Coetzee’s 1977 novel, In the Heart of the Country revolves around a similar plot involving a lonely young white woman on a remote farm. But Coetzee’s novel made a lot more sense in the heart of apartheid than does Farber’s post-scriptum. From the angry but beautiful Boer woman who hurls epithets at her black servant—“once a kaffir always a kaffir”—to the groveling but muscular black servant who alternately calls Julie a “bitch,” and tells her he loves her, the action swings from one extreme cliché to the other, allowing for contradiction but not for subtlety. Farber’s stage directions only augment the play’s bipolar dialogue (she wrote as well as directed) resulting in exaggerated, near-parodic scenes in which the characters either stomp enraged around the stage, skip in joy, or violently slap one another about before the culminating sex scene which is as harried and high strung as the rest of the performance.

The whole thing looks exhausting. The actors do well under the circumstances, but fail to transcend the script’s shortcomings. When Mies Julie ends her life in a gratuitously violent and bloody act—in Strindberg’s original she walks off-stage with a razor—instead of being shocked as I suppose we were meant to feel, I simply groaned. Violent self-mutilation in response to having sex with a black man is not, thankfully, the response of most white South African women who do so. While suicide may have been the only recourse for an aristocratic woman with no property of her own who sleeps with her servant in late-nineteenth century Sweden, Farber’s rote application of Strindberg’s plot to contemporary South Africa suggests that what is needed are new narratives to better describe the country’s actual state of affairs, disappointments and all. While Mies Julie’s violence, anger, and sex, feed audience desires for the dramatic, a more responsible theater of the present might eschew such sensationalism, making room instead for depictions of the history, love, and sex of everyday relations.

November 22, 2012

10 African films to watch out for, N°12

Here’s another list of 10 films in the making or already finished. Two long fiction features to start with. Dakar Trottoirs (directed by Hubert Laba Ndao; left) has “surrealist characters of a paradoxical theatre intermingling in the heart of the city.” Sounds real. There’s a write-up on the shooting of the film and a short interview with the director over at the curiously titled Africa is not a country blog (part of Spanish newspaper El País’s network). No trailer yet but check the film’s Facebook page for production stills, and you’ll find a short making-of reel here.

Here’s another list of 10 films in the making or already finished. Two long fiction features to start with. Dakar Trottoirs (directed by Hubert Laba Ndao; left) has “surrealist characters of a paradoxical theatre intermingling in the heart of the city.” Sounds real. There’s a write-up on the shooting of the film and a short interview with the director over at the curiously titled Africa is not a country blog (part of Spanish newspaper El País’s network). No trailer yet but check the film’s Facebook page for production stills, and you’ll find a short making-of reel here.

Next up, Andalousie, Mon Amour (“Andalusia, my love”) is Moroccan actor Mohamed Nadif’s directing debut, promoted as a comedy about migration. This one does have a trailer:

Three short films:

Nada Fazi (“It’s inevitable”) by João Miller Guerra and Filipa Reis is set in and engaging with the Casal of Boba neighbourhood (Lisbon, Portugal) where the majority of inhabitants is of Cape Verdian origin:

Another Namibian short (see last week’s list for more Namibian references) is 100 Bucks, directed by Oshosheni Hiveluah. You have to admire the Babylonic summing up of featured languages: English / Afrikaans / Otjiherero / Nama-Damara / Slang — with English subtitles:

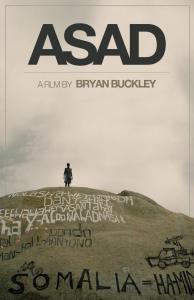

Coming of age fable Asad, directed by Bryan Buckley, was shot in South Africa (as a stand-in for Somalia), with a cast of Somali refugees. The film’s been raking in awards since it started circulating at international film festivals. Left’s the poster and here’s the trailer, while we wait for new films on or from Somalia that are not about pirates.

Coming of age fable Asad, directed by Bryan Buckley, was shot in South Africa (as a stand-in for Somalia), with a cast of Somali refugees. The film’s been raking in awards since it started circulating at international film festivals. Left’s the poster and here’s the trailer, while we wait for new films on or from Somalia that are not about pirates.

And 5 documentaries. One that showed at Bristol’s Afrika Eye Film Festival earlier this month: State of Mind, directed by Djo Tunda wa Munga (the trailer comes with a dramatic introduction and ominous muzak, but I don’t know of many other films engaging with anthropological, psychological — or whatever you’d like to name it — discussions about the potential effectiveness of applying old-school western psychotherapy in African contexts):

There’s also !Xun Electronica by filmmaker Paul Ziswe. Synopsis: “[multi-instrumentalist, jazz musician and producer] Pops Mohamed travels to the [South African] Northern Cape to the San community of Platfontein where he sets up a recording studio — and through the lyrics of the youth performed in !Xun and Khwe, as well as through the songs of the elders, a portrait emerges of this unique place”:

Outros Rituais Mais ou Menos is a film by Jorge António about a contemporary dance company from Luanda, Angola. Check Buala for a photo series by Kostadin Luchansky on the company’s latest production. Trailer:

Toindepi — Where are we headed? (Reflections from a Discarded Generation) focuses on life in Zimbabwe as seen through the eyes of More Blessing who lives in Hatcliffe Extension, a slum neigbourhood North of Harare, part of a city where residents have been victims of forced evictions campaigns. Here are some rushes:

And Shattered Pieces of Peace: South African director Dlamini Nonhlanhla’s first feature length documentary (prod. Sakhile Dlamini) tells the story of a mother whose relationship with her daughter crumbles following her public declaration of her homosexuality and HIV+ status:

The View from the Cape

“The fact is these Western Cape farm workers have been at the coalface of kakness for 350 years…” (Chester Missing, ‘Chardonnay, Best Served with Slavery’). Photo: Marcus Bleasdale.

When legal apartheid finally ended in 1994, South Africa’s new democracy faced one overwhelming challenge: to improve the lives of the country’s poor, or at least to maintain the hope that the future would be better. Yet with an enduring global economic recession, it can no longer be denied, not even by the eternal optimists of corporate South Africa, that the lot of the country’s poor has not sufficiently improved, despite ever increasing social grant distribution. And chances that their lives will improve, are slim. The destitute and working poor are now in an open and permanent revolt that flares up according to local conditions — they protest against a political and economic system that promised too much and delivered too little.

The so-called ‘service delivery protests’ are in fact a revolt of the poor that has intensified over the past few years and seems to be fuelled by a growing inequality and continuously rising living expenses that are eating away the little resources available to them. The hopes and aspirations of a better life after apartheid appear to be crushed by economic and social stagnation. What is apparent is that only the well-educated and well-connected, primarily most white people and the growing black (African, Indian, Coloured) professional class, are able to reach beyond the basic necessities and live the good life. While every year South Africa is subject to labour unrest when industry wages are re-negotiated, the recent violent confrontations between striking workers and police and private security operatives, can hardly be dismissed as ‘hiccups’, as the country’s president, Jacob Zuma, described them.

The brutal killing of striking miners by state security police in Marikana made it clear that the state is using repressive force to quell what are political protests over living conditions. The remilitarization of the police services initiated by the Zuma administration in 2008 bears much responsibility for a lethal state that has run out of ideas how to deal with the (violent) dissatisfaction of its citizens. Again, during the current farm protests in the Cape, reports of police brutality abound; the life of one farm protester at the hands of the police has already been claimed.

As in Marikana, business and government are insisting on adherence to and enforcement of the law — while the protesting workers have adhered to the law for 18 years of democracy without getting much in exchange. The law, apparently defined as primarily safety and security, as ‘keeping the peace’ through law enforcement, is increasingly being used as a political weapon to quell political activity from below. It becomes more and more difficult not to see this stance by government, in collusion with the biggest unions and in particular with organized business, as a war on the working poor and on dissent. Governance for the people is replaced with dismal politics in which human lives are mere pawns in a game for power and resources.

Revealing their mutual inability and unwillingness to address the basic needs of workers who are close to the breadline and fighting off ever-increasing costs of staple foods, the two major parties, the ruling African National Congress and the Democratic Alliance (they run one of the 9 provinces, the Western Cape, and a major city, Cape Town), indulge in costly politicking.

Poverty and revolt, protest and repression, violence and resistance, citizens rights and duties, governance and accountability; in short, mutual obligations that form the foundations of a modern polity have become the plaything of political point scoring.

In the Western Cape, the scene of protests by farm workers in the last few weeks, the DA and the commercial farmers’ union, Agri SA (mostly white farmers), allege orchestrated ‘third force’ intervention by the local ANC opposition while the ANC in turn recriminates about the DA’s failure to protect the workers and the break-down of good governance in the province.

The ANC (which condemned striking workers at Marikana) downplays the political significance of the strikes in the Western Cape and claims they are about labour relations rather than politics. The DA claims it is a political conspiracy but ignores that it has much to do with the particular conditions in the Western Cape. For years, farm workers have been trapped in insecure and hard labour with little pay and even less prospects for improvement. In addition, the tribal and xenophobia card is being played, blaming the unrest on foreign workers.

So both parties are part of an anti-politics machine that practices apolitical revisionism — for the DA, there is no particular historical legacy in the Cape that needs scrutiny, while for the ANC, all the protest is just about labour relations in which the breakdown of legitimate politics of representation plays no role. As Achille Mbembe observed, the ANC’s vision for the future for society is to live like the country’s white people; this seems to be understood as a life based on nothing else but ever rising consumption and a mindless entertainment lifestyle. Competition for state resources that enables the vulgar display of wealth seems to be the prime motivation to join the once proud liberation movement — as the party sinks deeper into infighting for spoils, the question remains if clear heads who call for an overdue self-renewal will prevail over political careerism and the outright looting of state and society.

In contrast to most of the mainstream (media) opinions who bemoan the lack of docility of an exploited and hungry work force, black commentators such as Phylicia Oppelt and Fred Khumalo in the Johannesburg Sunday Times (November 18, pp. 6-7) see the legacy of slavery and a paternalistic past very much alive in the current Cape labor regime and social relations, as well as continued racial segregation despite democracy and the abolition of white supremacy. White supremacy, as manifested in racism, xenophobia, and tribalism, is then still very much alive — in Gauteng’s Marikana, as well as in the Cape’s De Doorns. When a more recent report (by Human Rights Watch) — one among many (see for example here, here or here) — about the plight of farm workers was published, DA leader (and Western Cape Premier) Helen Zille did nothing more than criticize it and claimed that it does not represent reality because the sample size was allegedly too small. One can only wonder about the kind of social science research that is compliant with the DA’s political agenda.

Business leader Mamphele Ramphele (she was active in the Black Consciousness Movement in the 1970s) has pointed to the now apparent crisis of legitimacy of an elite compact between the old white elite and the new black elite at the expense of the poor — while this perspective perhaps aptly points fingers at a dismal political solution to end apartheid that left the economy untouched, it seems as if Ramphele’s own involvement with local and global multinationals, including the World Bank, blinds her to the profound lack of future perspectives within neoliberal corporate ideology and practice.

Liberal economists are correct to point out that wage increases in the agricultural sector, now very much in the offing as the state’s response to the farm workers’ strike, will even more reduce rural employment in the long term and the likelihood that workers in rural areas will have a chance to find employment. However, it is cynical that those who benefitted from slavery and apartheid wish an uncomfortable truth about the past away and admonish us that the laws of neoliberal economics are such that today’s workers should be happy that they can be exploited, as there are always those who cannot even work, and are even poorer and more desperate to take up any work, how little the pay. The same comments were made about the Marikana miners. If the solution to reducing rural poverty, in South Africa and across the globe is only sought by increasing production, as neoliberal economists allege, then little can be done to sustain a decent living for all. Rather, a paradigmatic shift is called for and the current administration’s infatuation with the developmental state or with China as a model to emulate do not show signs of new thinking. In contrast, as the proponents of an economy that is based on human needs argue, the “project of economics needs to be rescued from the economists” — the nefarious influence of neoliberalism on economics has to be replaced. Even within the Cape farm region, initiatives involving farm workers and the equitable distribution of work, profits, land and other resources, offer an alternative to current, neoliberal practices.

The farm workers’ strike reminded us that the Western Cape is very much part of this country and continent, despite constant efforts to single out the region for exceptional good governance that, however, leaves out the plight of the working poor and the continued racial discrimination so prevalent in a Cape province that sees itself as an outpost of Europe and a carefree California — a playground for the global rich and fashionable, rather than a postcolonial African region, with all its opportunities and challenges.

The Trouble with the Nigeria Prize for Literature

The richest literary prize in the world, the Nobel Prize, carries a US$1.1 million purse. The richest lit prize in Africa, the NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature, doesn’t quite match up, but it does guarantee the winner a whopping US$100,000. It’s been around since 2004, with the purse increasing from $20,000 to $40,000 in 2006 and finally to $100,000 in 2008. The latest prize, awarded at the start of November, went to Chika Unigwe for her novel “On Black Sisters Street.” Though there has been widespread praise for Unigwe across the Naijanet, talk of the politics of her win has been muted.

The richest literary prize in the world, the Nobel Prize, carries a US$1.1 million purse. The richest lit prize in Africa, the NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature, doesn’t quite match up, but it does guarantee the winner a whopping US$100,000. It’s been around since 2004, with the purse increasing from $20,000 to $40,000 in 2006 and finally to $100,000 in 2008. The latest prize, awarded at the start of November, went to Chika Unigwe for her novel “On Black Sisters Street.” Though there has been widespread praise for Unigwe across the Naijanet, talk of the politics of her win has been muted.

These politics have been addressed before, but critiques focus mostly on the kinds of novels — those that confirm Westerners’ pessimism and faithlessness about Africa’s future — that tend to win. Thus far, talk of who sponsors the prize and why that matters has been nonexistent.

In the case of the $100,000 attached to the Nigerian Literary Prize, the money comes from Nigeria LNG Ltd. NLNG is one of Nigeria’s petroleum sector giants, producing around 10% of all liquefied natural gas (LNG) consumed globally each year. The notoriously corrupt Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation owns a 49% controlling stake in the company; the remaining shares are held by Shell (25.6%), Total (15%), and Agip (10.4%). Reports on NLNG’s role in individual spills and human rights abuses are hard to come by — maybe because Shell works overtime to cover up its wake of destruction — but there exists plentiful hard evidence of NLNG’s shady business practices. Of course, any company with direct links to Halliburton should be watched with a careful eye.

Activists in Nigeria have long insisted that firms operating within Nigeria’s impossibly complex oil economy must be held accountable for the murkiness that characterizes the sector’s business deals. So too must they answer for the lack of jobs and poor living standards that have continued to define life for most Nigerians, all while their country’s oil wealth seemingly vanishes into thin air.

To what extent has NLNG used the illusion of corporate philanthropy to clear its name in the eyes of the public writ large? The always-reliable Arundhati Roy recently addressed similar questions in a piece for India’s Outlook Magazine.

Her article is mainly focused on the vagaries of Indian electoral and “civil society” politics, but halfway through she shifts her attention to India’s big businessmen and their foundations. She writes them into an account of business’ links to philanthropy as it emerged first in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century. While these foundations were initially attacked as distractions or as whitewashing attempts — “if companies had so much money,” the argument went, “they should raise the wages of their workers” — over time the material gifts that corporate foundations provided, and the real good they did, muted the criticism. Roy reminds us of the real intentions behind corporate giving:

Like all good Imperialists, the Philanthropoids set themselves the task of creating and training an international cadre that believed that Capitalism, and by extension the hegemony of the United States, was in their own self-interest. And who would therefore help to administer the Global Corporate Government in the ways native elites had always served colonialism. So began the foundations’ foray into education and the arts, which would become their third sphere of influence, after foreign and domestic economic policy.

What’s behind NLNG’s decision to offer such a large annual award for literature, as well as its equally large prize for scientific research? Is it a coincidence that, as the company’s corrupt practices came under increased fire in 2008, it increased the value of the award by over 200%?

And what of those who accept the prizes? One can easily argue that artists and scientists, perpetually squeezed for cash, need the money (at least if we buy the stereotype of the starving artist). And because winners are not censored in any way, what’s the harm in accepting the prize money, especially if it helps them to create more affecting art or to make new scientific breakthroughs in the future? Roy addresses these questions toward the end of her article, excusing those poor young Indians that accept grants from foundations with questionable origins and intents. “Who else is offering them an opportunity to climb out of the cesspit of the Indian caste system?” she asks. It’s a fair question. But Unigwe isn’t stuck in the cesspit of a caste system. She’s not even crawling through the urban chaos of Lagos. She’s in Belgium, far from the tainted oil that paid for the prize.

It is reasonable to expect that NLNG uses its awards as marketing tools, to distract Nigerians from the issues it creates on the ground, in real life, every day.

Should that matter to prize winners? Should it matter to Unigwe?

November 21, 2012

The end of “the colonial gaze”?

The weekend after Hurricane Sandy hit NYC, AIAC’s Sean Jacobs and I (we’re academics in our day jobs) attended Encounters with the African Archive, a symposium at New York University. The symposium coincided with the exhibition series Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive at The Walther Collection Project Space, and was intended to create an opportunity to “exchange, debate, and open up the categories—colonial, ethnographic, anthropological, and artistic—that are often used to describe historic and contemporary photographs of Africans.” The end result of all of this—the symposium and the three-part exhibition—will be a book. A couple of the presenters and respondents began by expounding passionately about the need to get away from the overused phrase, the “colonial gaze”; some respondents and presenters expressed irritation that students throw “colonial gaze” out almost as often as the phrase “male gaze” when they critique photographs. It seemed, by the middle of the symposium, that anyone referring to the existence of said offending gaze—quite obviously present in the reams of beautiful, complex, and sometimes troubling Walther Collection photographs—would inevitably be labelled as irritating and passé as the hapless, inexperienced student of photography who jumped too quickly to employ that phrase. By the end of the day, the respondents who decried the overuse of the “colonial gaze”—and had asked if we could just “pretend” for a moment it doesn’t exist so that we could somehow move beyond it—were gracious enough to admit the possibility that it was, in fact, present in some of the photographs discussed by a South African presenter. However, it was also proposed (though disputed afterwards) that in other areas of Africa (where colonialism had possibly created less of an impact), this ‘gaze’ did not present a problem to photographers.

The weekend after Hurricane Sandy hit NYC, AIAC’s Sean Jacobs and I (we’re academics in our day jobs) attended Encounters with the African Archive, a symposium at New York University. The symposium coincided with the exhibition series Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive at The Walther Collection Project Space, and was intended to create an opportunity to “exchange, debate, and open up the categories—colonial, ethnographic, anthropological, and artistic—that are often used to describe historic and contemporary photographs of Africans.” The end result of all of this—the symposium and the three-part exhibition—will be a book. A couple of the presenters and respondents began by expounding passionately about the need to get away from the overused phrase, the “colonial gaze”; some respondents and presenters expressed irritation that students throw “colonial gaze” out almost as often as the phrase “male gaze” when they critique photographs. It seemed, by the middle of the symposium, that anyone referring to the existence of said offending gaze—quite obviously present in the reams of beautiful, complex, and sometimes troubling Walther Collection photographs—would inevitably be labelled as irritating and passé as the hapless, inexperienced student of photography who jumped too quickly to employ that phrase. By the end of the day, the respondents who decried the overuse of the “colonial gaze”—and had asked if we could just “pretend” for a moment it doesn’t exist so that we could somehow move beyond it—were gracious enough to admit the possibility that it was, in fact, present in some of the photographs discussed by a South African presenter. However, it was also proposed (though disputed afterwards) that in other areas of Africa (where colonialism had possibly created less of an impact), this ‘gaze’ did not present a problem to photographers.

I had visited the exhibition in Chelsea before the conference and the photographs in the Walther collection defy attempts to relegate them into easy, narrow readings. It juxtaposes the stereotypical “native” photographs of the early 20th century ethnographer-photographer A.M. Duggan-Cronin against portraits from the same period that black South Africans had commissioned for themselves. The latter was collected by South African photographer, Santu Mofokeng, who is associated more with social documentary photography from the 1980s. (The image above is from the exhibition: on the left is an image collected by Mofokeng; on the right one taken by Duggan-Cronin.)

Clearly, I wouldn’t want my students (or me) to employ a stock phrase in order to box in such complex images and their history. But I remained troubled: what about the resonances of the same obsessions with African albinos and broken down states in current photography—particularly in Pieter Hugo’s and Guy Tillim’s work (associations and resonances brought to our attention by another presenter)? And if a Ghanaian or a Congolese were to go to France, England, Germany, wouldn’t she/he find that conversation with historical imagery and narrative lines—ever present in our conversations and image banks—to be ongoing? Or conversely, if a European were to visit an African country? And: if, indeed, the colonial gaze has gone the way of childhood fantasies, why do we still have popular TV programmes like Discovery Channel’s “Jungle Gold”? The programme, set in Ghana, depicts two American adventurers (two Utah-based real-estate speculators whose businesses recently went bust rock up in Ghana in search of gold) as dutiful family men who embark on this arduous journey to provide for their loving families. Ghana here is just a backdrop: it is Africa as a savage and desperate place, teeming with muddy men with guns and pangas who block the roads, demand constant bribes, and generally threaten the American duo’s lives and plans. Even the use of the word “jungle” presents us with certain obvious associations that I don’t even need to expand on.

Hello, colonial gaze.

The history of photography and art is embroidered with the politics of conquest, desire, and race. In the multivolume book project, Image of the Black in Western Art, edited by David Blindman and Henry Louis Gates, we get to see how we, as people bring our current modes of looking, continue to be involved in that historical conversation. From slaves to saints, wise men, aristocrats, and ‘mulattos’ in court, Africa’s encounters with Europe and Europeans did produce aesthetic moments of tender attention to the particular and the individual. But of course, from the initial periods of tentative trade to the Early Modern period which experienced more cosmopolitan rapport with otherness, the more common depictions of Africa positioned it as a place of freakish practices, beasts, and violence-prone peoples who were particularly (and contradictorily) amenable to slavery and servitude. It hardly needs to be said that these ubiquitous images—and the accompanying politics of race and ways of seeing—still inform and re-enters our presence-ing of Africa and African subjectivities.

It’s true that Duggan-Cronin’s work cannot be easily dismissed by a simplistic analysis. Though he set out to frame his subjects as ‘tribals’, he inevitably finds them describing themselves, each other, and their close others in very modern ways. And we can still discover those self-descriptions, leafed in between images depicting exoticism and strangeness: For example, “Plate CXCVIII: Two Young Dandies” shows “Two friends, dressed in their finery,” meeting on their way to a wedding, discussing “possible conquests at the nightly love-making (ukubiza).” And Plate CLXI, “Storing Mealies in a Grain Pit” shows us how the Hlubi regarded the Baca, outside of European gaze; it reminds us that these ways of looking at self and other are no different, say, from the way that French Alsatians may regard German Alsatians:

It’s true that Duggan-Cronin’s work cannot be easily dismissed by a simplistic analysis. Though he set out to frame his subjects as ‘tribals’, he inevitably finds them describing themselves, each other, and their close others in very modern ways. And we can still discover those self-descriptions, leafed in between images depicting exoticism and strangeness: For example, “Plate CXCVIII: Two Young Dandies” shows “Two friends, dressed in their finery,” meeting on their way to a wedding, discussing “possible conquests at the nightly love-making (ukubiza).” And Plate CLXI, “Storing Mealies in a Grain Pit” shows us how the Hlubi regarded the Baca, outside of European gaze; it reminds us that these ways of looking at self and other are no different, say, from the way that French Alsatians may regard German Alsatians:

The Baca store their grain in pits (itisele), bell-shaped chambers dug under the cattle kraal, covered by a flat stone and sealed with dung. The grain tends to ferment and the air in these pits become foetid; often young children, let down into he pit to get grain, are overcome by the fumes and have to be hauled out quickly. Although Baca consider such grain a delicacy, the nearby Hlubi, who store their grain in baskets, comment, “We bury our dead, not our food!”

The Walther Collection Project Space’s three-part exhibition series on photography from Southern Africa presents us with opportunities for negotiating the ways in which we encounter the offense inherently imbedded in that colonial gaze. The first in the series sets Mofokeng’s collection of South African family photographs together with Duggan-Cronn’s colonial photographs of South Africa (published in eleven volumes, between 1928-1954, under the title The Bantu Tribes of South Africa). Mofokeng’s The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890-1950 (published in 1997) is an archive of portraits, each of which were commissioned by black South Africans in the same era in which Duggan-Cronin was busy ‘tribalising’ South Africans using the same medium. By presenting these ‘other’ archival photographs of black South Africans as they saw themselves, Mofokeng seeks to begin a conversation with the colonial gaze, contextualising colonial images, photographs, and postcards. Here, he challenges fixed ideas of the “native types” or “tribals” most often associated with photographic representations of Africans from Duggan-Cronin’s era, ideas which continue on in our own moment in history. The exhibition invites us—the current inheritors of these complex legacies—to seek to transcend, while acknowledging the impossibility of erasing or “pretending” them into non-existence.

Like Mofokeng, and the curators of these collections, I would rather find ways to exuberantly engage with that all knowing gaze and accompanying epistemologies on Africans. In fact, young digital curators and photographers already are messing with those stock images of the native and the African, using Tumblr, Pinterest, and WordPress. That living digital archive may be where we need to head to next, as the moving locations on which we actively engage with remarking upon, questioning, and remaking self and history.

If you are in the (U.S.) East Coast: The Walther Collection’s opening reception for “Part II: Contemporary Reconfigurations” is on Thursday, November 29, from 6pm-8pm at their Chelsea Gallery. And: Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (the collection will travel to Princeton University Art Museum from Feb. 16-June 9).

November 20, 2012

General Focus of Freetown

This summer I received an email from my friend Anusha about a young inventor in Freetown. The story really made me laugh because while being quite unique, it also really summed up a lot about the nature of social navigation for all types of young people in Sierra Leone:

there is a 12 year old kid called General Focus, he has this amazing talent of making things on his own, generators and what not. He has a pirate radio station that broadcasts music a couple of times per week and he ‘”employs” his friends as the dj’s. He used to call himself DJ Focus, but has now upgraded to General Focus, because he manages things and makes sure they don’t play bad music — and that’s a quote. He pays the dj’s 5000 leons per month…

In September, with the help of Innovate Salone and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.), General Focus made his way to the U.S. to attend the Maker Faire in NY, and take up a brief residency as the M.I.T. International Development Program’s youngest ever visiting practitioner.

This past weekend, news about Kelvin spread perhaps faster than news about the country’s elections, via the above documentary posted to YouTube on Friday. The profile has gotten close to 300,000 views in a few days, showing that the world seems moved by this young genius and the really inspirational work of “big brother” David Sengeh. But, if you really want to get an understanding of how exciting such young innovators are for Sierra Leoneans, watch the man interviewing Kelvin in the clip below. He can barely contain his excitement at the prospect of a radio station at Bo School!

The Inventor from Freetown

This summer I received an email from my friend Anusha about a young inventor in Freetown. The story really made me laugh because while being quite unique, it also really summed up a lot about the nature of social navigation for all types of young people in Sierra Leone:

there is a 12 year old kid called General Focus, he has this amazing talent of making things on his own, generators and what not. He has a pirate radio station that broadcasts music a couple of times per week and he ‘”employs” his friends as the dj’s. He used to call himself DJ Focus, but has now upgraded to General Focus, because he manages things and makes sure they don’t play bad music — and that’s a quote. He pays the dj’s 5000 leons per month…

In September, with the help of Innovate Salone and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.), General Focus made his way to the U.S. to attend the Maker Faire in NY, and take up a brief residency as the M.I.T. International Development Program’s youngest ever visiting practitioner.

This past weekend, news about Kelvin spread perhaps faster than news about the country’s elections, via the above documentary posted to YouTube on Friday. The profile has gotten close to 300,000 views in a few days, showing that the world seems moved by this young genius and the really inspirational work of “big brother” David Sengeh. But, if you really want to get an understanding of how exciting such young innovators are for Sierra Leoneans, watch the man interviewing Kelvin in the clip below. He can barely contain his excitement at the prospect of a radio station at Bo School!

November 19, 2012

Yannick Nyanga’s Tears

Last week, before a rugby test match between France and Australia in Marseille, as the French national anthem, “La Marseillaise,” began playing, Kinshasa-born rugby player Yannick Nyanga began sobbing uncontrollably. It went viral. [See video below.] Nyanga then helped his team to demolish Australia’s, with France winning 33-6, a victory soon forgotten as the post-match media attention focused on his pre-match emotions.

For Nyanga it was simple, as he told a reporter from the AFP: he was happy to be back on the French team after a 5-year hiatus, caused by a knee injury and former coach Marc Lièvremont’s decision not to pick him.

Much to Nyanga’s dismay, a lot of the discourse around his public display of emotion has centered not on his return to test rugby or to big French win, but rather what it says about French sportspeople and patriotism. In this, Nyanga’s actions were contrasted with those of France’s national football team.

France’s football team has been shamed as arrogant, overpaid athletes, most especially for their showing, or lack thereof, in the 2010 South Africa World Cup. Most of the football team was black and as some, like Laurent Dubois, have shown—summarizing debates in France for an English audience—that’s not irrelevant in French sports and media politics (see also the “too many blacks and Arabs” scandal).

Nyanga was not oblivious to what he had wrought. He told AFP: “My tears really created a buzz (on social media as well as the regular media) despite myself.”

An example of how Nyanga’s actions were jettisoned for French nationalist politics, check Philippe David’s post on the French blog Atlantico: “He’ll be 29 next month, and his skin may be black but for him, hearing “Let us come, patriotic children” [words from the anthem] and wearing a jersey with the symbol of the cock on the sleeve, brought him to tears … we are reminded that being French is not about a skin color nor a religion.”

Underneath the YoutTube video of Nyanga’s now famous tears, the most popular comments underscored French pride even further: “Now THAT’S France! Not like those lousy footballers.” Or, “Maybe the TEAM OF FRANCE should take notes from our magnificient XV!”

Twitter had its turn too. A few users compared Nyanga to Obama: “Yannick Nyanga > Barack Obama.” Another tweeted, “Yannick Nyanga’s tears are unforgettable.”

One particularly right-swinging Française blogged about “the tears of Yannick Nyanga, our brother”, while simultaneously strongly endorsing the French film Case Départ. (The latter is perhaps a first of its kind, a comedy about two modern-day Black half-brothers who are magically transported to the time of slavery in the French West Indies. It has been a highly controversial film, with many arguing that making light of the history behind French enslavement is unacceptable in a country like France, where many Black people are subject to racialized treatment, and occupy menial positions.)

Nyanga, however, wasn’t particularly feeling the debate between rugby players and footballers:

It serves no purpose to stir up these debates, it is ridiculous. It is pointless to make such comparisons, to be divisive. [The tears] were a personal reaction. I had worked really hard for something that I was desperate to have: to wear the French shirt.

Whatever Nyanga may have thought, football players (and supporters) did not not notice nor care for his touching moment.

Julien M tweeted: “’Ribéry: Hey Karim, did you see Nyanga crying during the anthem? Benzema: Yea! I laughed too hard!’ Tonight, it’s football!”

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers