Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 507

December 12, 2012

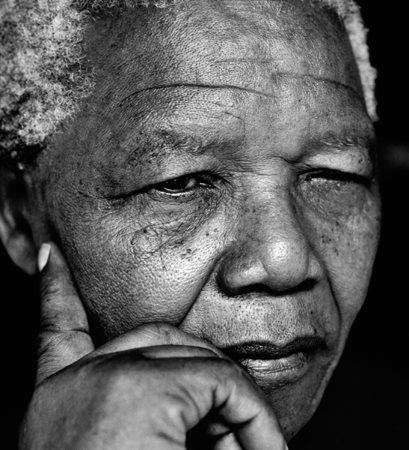

When Nelson Mandela goes

Yesterday we tweeted my friend Herman Wasserman’s guide to the media on how to cover Nelson Mandela’s hospitalization (it’s good advice if you’re a journalist). This morning I asked Nathan Geffen, a South African media activist (and author) whether we could republish here his post on the “when Mandela goes” meme. Geffen is one of the key people behind the groundbreaking, very non-mainstream, community news portal GroundUp. Here’s the post:

Guest Post by Nathan Geffen

Madiba is in hospital. Spokespeople assure us he is doing well. That he is old, sick and likely to die soon are avoided or dealt with euphemistically. The tip-toeing around Mandela’s mortality encourages the idiotic myth-making by self-styled experts on South Africa who don’t live here. Some of them are downright ridiculous suggesting that the country will unravel when Mandela dies. A version of this myth was written on Monday by David Blair in the British newspaper The Telegraph. He wrote “For as long as he is around, South Africans believe their present leaders will be slightly more likely to stick to the principles of the nation’s rebirth 18 years ago. In a way that foreigners can’t really grasp, Mandela still underwrites that settlement with all its promise and idealism.”

Well I’m South African and I don’t believe this. Frankly, Mr Blair, I suspect you’re talking nonsense. Mandela retired from politics several years ago. He has had hardly any role in recent South African politics. Our country holds together not because of the Nelson Mandela of today, but because of what he did over his lifetime which is now sadly but inevitably winding down. It also holds together because we have a more or less functioning constitutional democracy and innumerable countervailing forces: powerful unions, powerful civil society activist organisations, powerful opposition parties, some good people still left in the ANC, powerful businesses, some effective courts, a free and vibrant media. There are no guarantees: South Africa might descend into the abyss — and another term of office for President Zuma increases the risk of this — but I think it unlikely. Nevertheless, whether or not South Africa thrives, unravels or — the most likely scenario — just continues to bumble along, is not dependent on Nelson Mandela staying alive.

Nelson Mandela is a great person, one of the greatest of the last 100 years. Despite growing up in a rural homestead with limited opportunities he invested heavily in his education and became the most respected African ever. He spent 27 years in prison to defend his principles but forgave his captors and used his leadership to mitigate South Africa’s civil war. He helped defeat apartheid and helped South Africa become a reasonably stable albeit flawed democracy. History is not the product of a single person’s actions, but it is conceivable that without Mandela, South Africa’s political settlement might not have been achieved and the country would have descended into chaos. Yet Mandela is human and he has also made mistakes. As with all great people who have had to make many very difficult decisions throughout their lives, sometimes he made big and bad mistakes: his handling of AIDS in the 90s and his passing the baton to Thabo Mbeki were two of his bigger ones. He realised the former, apologised for it, and appeared to have realised the latter. He made amends by confronting Mbeki’s AIDS denialism which helped change government’s AIDS policies. His decision to turn the ANC to armed struggle will always be controversial. Overall his greatness far, far outshines his errors.

But Nelson Mandela is mortal. He’s also old. He is 94 and in obviously very frail health. It might be 10 years from now, 5 years, in 2013 or even in the next few weeks, but he is absolutely, unequivocally, unavoidably going to die, as are we all.

Moreover, most very old people begin to lose their mental faculties. It’s by time someone said it publicly. After all, most of us talk about it privately: Madiba is losing his mental faculties. Only those closest to him know how seriously he is losing his faculties but we all know, from several public clues, that there is some loss and it appears to be quite serious. It is sad, but there should be no shame in this and no embarrassment. It does not tarnish his legacy. What’s happening to him is a natural part of life and death and it’s by time we said and accepted it, openly, publicly and without euphemism. The currently living Nelson Mandela no longer has any substantial influence on South African politics. On the other hand, his lifetime’s work and our memories of what he has achieved have a profound influence on South Africa and the world. They will continue to do so long after he has died.

The myth-making about Mandela, the continued suggestion by the ANC that he’s infallible and superhuman and the pretence by the opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, that it carries his mantle, coupled with the failure to critically discuss and debate his lifetime’s ideas, actions, successes and failures, does him a disservice. It reduces his life to feel-good quotes and excuses all kinds of bad behaviour done in his name. This dehumanises Mandela and actually means we fail to learn from his achievements.

It is sad when people we love become old, frail and ill. It is sad when they die, but it is an unavoidable and necessary part of life, of how the human species works. Death is tragic and inevitable but it’s also ok, because there isn’t an alternative.

It is insulting to Mandela to suggest that his lifetime’s work will unravel at the end of his lifetime. Let us give Madiba the respect he deserves by recognising his humanity, his frailty, his decline, his mortality and that life will go on when he dies.

* This is republished (in slightly edited form) with kind permission from GroundUp. You can follow Geffen on Twitter @nathangeffen.

Mozambique, the new frontier of global capitalism

Recent business reporting on newly discovered natural resources in Eastern and Southern Africa evokes a new frontier for explorers on the Indian Ocean: Mozambique, Kenya and Tanzania have become the center of an “energy boom” and thus, in the words of The Economist, the new “El Dorado,” the lost city of gold. This frontier fantasy raises hopes in a sector that needs to adapt to new challenges, and Mozambique, in particular, is at the center of attention with “four of the five largest oil and gas discoveries in the world this year.” What is being cultivated at the new frontier of global capitalism—and for whom?

Off the Mozambican coast, the Italian company Eni has been exploring gas deposits and regularly made news this year with new finds. The New York Times estimates that Mozambique may have larger gas deposits than Norway, the “emirate of the north,” and expected export levels would put the country in the league of Qatar and Australia. Not just Western companies are involved in the resource hunt, however. Further inland, the Brazilian company Vale is building the world’s biggest coal mine, reviving coal production in Central Mozambique after it had been interrupted by the post-independence war that ravaged the country from 1976-1992.

That Mozambique is a place for economic opportunities is nothing new, of course. Many Brazilians and Portuguese, having trouble finding jobs at home, have moved to Mozambique in recent years to try their luck—and often succeed. Plenty of South Africans in Maputo take advantage of the proximity of the Maputo port and engage in import/export business in the neighboring country.

Where does this leave Mozambicans? Al Jazeera speaks of a “crucial juncture” in Mozambique’s development. The country has experienced steady growth of 6–8 percent over the last years, which is expected to rise once gas exports begin in about ten years’ time. While most Mozambicans have yet to see any effects, positive or negative, of the discoveries, prices have already risen sharply in Pemba, the capital of the province Cabo Delgado on the Indian Ocean, due to the influx of foreign workers linked to gas exploration companies. In the coal sector, effects have been felt more severely. Earlier this month, again, The New York Times shed light on the other side of the coal boom—the people left behind by international companies that don’t deliver on their promises to build schools and employ locals. Vale, the coalmining company operating the mines in Moatize, in Mozambique’s Tete Province, was just awarded the title of the “most evil corporation” 2012 for its “human rights abuses, inhumane working conditions and the ruthless exploitation of nature.”

Far from taking such criticism as an opportunity to make international corporations more accountable, Mozambique’s president Armando Guebuza accused unnamed foreign “professional agitators” of creating discord among Mozambicans. At the recent congress of the Mozambican Workers Organization (OTM), he said that such agitators “in the name of friendship with the poor are sowing an atmosphere of intrigue among Mozambicans.” This rhetoric is reminiscent of wartime language. The “war of destabilization,” as many Mozambicans call it, was long blamed entirely on Rhodesia and South Africa, major supporters of the then rebel army Renamo. The curious thing here is, though, that—although mostly foreign—global capital is left out when it comes to identifying the scapegoat for discontent among Mozambicans. Until the government under Guebuza’s party Frelimo finds a way to regulate the exploitation of the new finds and split its benefits among all Mozambicans, international explorers will have enough time to divide up the re-discovered lost city of gold amongst them.

* Corinna Jentzsch is a graduate student in political science at Yale University.

Renouncing the Rhino

I used to like Rhinos, I never loved them, but I thought they were pretty cool. I once even saw a couple in the wild with my parents in Kruger National Park. Sadly, like so many other things, rhinos have been ruined for me. I can’t like them anymore. I don’t dislike them personally, but I hate what they have come to represent. Don’t get me wrong — rhinos are blameless in this scenario. Rhinos can’t help that their horns are a valuable commodity with a high demand in parts of Asia and they live near lots of desperate people or that some rich Americans like to travel to the dark continent to kill things.

My beef with rhinos is more of a beef with white South Africa as a whole (yes I know I’m a white South African). What gets to me is the Sandton, Constantia or “insert fortress suburb of your choice” housewives in their oversized SUVs, who listen to Freshlyground (’cause they aren’t racist) and shop at Woolworths, when they venture out of their gated communities and who now place red plastic horns on the bonnet to show their solidarity with the rhinos. Dubbed the “Rhinose,” these horns are even made of recycled goods and fit right in with your Eco-friendly Golf estate and fair trade coffee.

Also to blame are the trance ‘hippies’ who claim to be progressive — some even call themselves anarchists — and who are into the whole new age pacifist scene, but yet regularly call for the deaths of rhino poachers. Or the same people who clog my Facebook wall with calls to save the rhinos and send me hundreds of different Avaaz petitions.

What all of these different social groupings have in common, besides being mostly white, is that while they have endless time for the rhino they have little or nothing to say about contemporary South Africa. Little or nothing, beyond the normal white persecution complex which endures in the form of calls for Woolworths’ boycott or calling Black Economic Empowerment (or the University of Cape Town) entrance requirement “reverse apartheid.”

When the state gunned down 34 miners at Marikana for asking for a living wage, they were silent. Hell, I saw plenty of people suggest that they had it coming because they were ‘unskilled’ and uneducated. I’ve seen far more of these plastic horns than say “Justice for Marikana” stickers on cars. No Facebook likes or Avaaz petitions, even.

When farm workers in the Western Cape went on strike for a minimum wage of R150 a day ($20) they were silent again. They are largely silent about inequality, poverty and institutional racism. In a country in which unemployment hovers around 40% overall, around half of the country lives below the poverty line and we can boast of being the second most unequal society in the world after Namibia.

It’s kind of hard to miss social realities in such an environment.

This is a country in which the game was and largely continues to be rigged in favor of white people, who still continue to deny they benefited and continue to benefit from Apartheid. How many white South Africans actually admit to having voted for the National Party (they ruled South Africa between 1948 and 1994)? This is a country where you have to be intentionally ignorant to deny the reality of racial inequality; one has to ignore the millions living in shacks or the sheer extent of desperation in a country where people are prepared to die for R150 a day.

Maybe I’m just anthropecentric, but where was this voice of the moneyed middle class when the state committed the worst act of mass violence since Apartheid? Also, where were they when video of community activist Andries Tatane was broadcast on the evening news, or when Western Cape Premier Helen Zille ordered local police to invade Hangberg? I know. I saw far more sorrow and anger over the Rhino issue.

At my Alma Mater, Rhodes University, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, there was not one public meeting in the aftermath of the massacre, but I can recall numerous campaigns to save the Rhino and at least one mural put up on a wall outside the library. Ironically, the same people — who when you can eventually get them to talk about politics endlessly bemoan the corruption and incompetence of our current government — reflexively sympathize with the state when it illegally breaks up protests or shoots poor black people. But at least they speak up for the voiceless rhinos and even buy the rhino friendly bags from Woolworths (yes these exist too).

For these reasons, I hate rhinos, they symbolize the sheer disjuncture between white South Africans of fortress suburbia and the struggles of a country still attempting to realize some measure of social justice for the vast majority. For me, it shows that for the majority of white South Africa, black life still means very little — if anything at all. Animals for them are more important than human life.

It seems like far more outrage was expressed over a T-shirt containing the words “I benefited from apartheid” than over the fact that people are earning R69 a day in the farms or that millions of black children go bed hungry in shacks every night. Obviously, there are exceptions to this, but I’m not indulging in hyperbole when I say that I’m not being unfair to the majority.

I’m not renouncing the rhino because I want to claim the moral high ground or because the plastic rhino horns look like dildos or because I want to maintain a measure of dignity. I’m doing it because I refuse to be complicit in apolitical narcissism that still prevails amongst white South Africans. Rhino politics, if it’s not matched with the same focus on humans, belongs in the same dustbin of history — #Kony2012 replete with Jason Russell’s public masturbation included.

White South Africans probably won’t suddenly take to the streets in solidarity with striking black workers or decide to pay farm workers more than starvation wages, but I hope at least some of us can end the denial and start contributing to this country in a serious fashion. Or if not at least sign the Avaaz petition.

* Benjamin Fogel is a freelance journalist based in Cape Town, South Africa. He writes about politics and in his spare time listens to hip hop and rants. He can be contacted a t benfogel@hotmail.com.

December 11, 2012

Six lessons from Ghana’s 2012 elections

[image error]

Ghana held its sixth consecutive elections since its democratic transition in 1992 this past weekend and once again has earned its reputation as a stable and thriving democracy, in spite of predictable cries of fraud by the losers, the New Patriotic Party (NPP). As I predicted here before the elections, Ghanaians elected the incumbent president John Dramani Mahama in a close vote and his party, the National Democratic Congress (NDC) expanded its majority in parliament. Mahama, who took over as president in June when then-President John Ata Mills died, faced the NPP’s veteran leader Nana Akufo-Addo in Friday’s polls. Mahama’s “one-touch” victory–meaning a second round run-off election was avoided–was not unexpected, since he led Akufo-Addo in independent polls before the vote. Nonetheless, there were surprises, such as the defeat of several prominent parliamentarians and the record number of women elected to the legislative body (29 out of 275 seats). As Mahama sets up his transition team and the NPP threatens to challenge the results in court, here are six lessons from Ghana’s sixth elections:

1. Not only is Akufo-Addo the Ghanaian Mitt Romney, but the NPP are the Republicans of Ghana. Like their ideological cousins in the United States, with whom they share the symbol of the elephant, the NPP was so confident of victory that they were totally unprepared for defeat. No NPP representatives attended Sunday’s press conference at which Dr. Kwadwo Afari-Gyan, Chairman of Ghana’s Electoral Commission, announced the official results and the party is claiming electoral fraud, as they have every time they have lost an election since 1992. Yet, their support base is limited mostly to the Asante and a few related Akan ethnic groups, as evidenced by the fact they won only two of Ghana’s ten regions, and every one of its presidential candidates has come from these two regions. The ruling NDC is a national party, drawing support from all of Ghana’s major ethnic groups, and each of its three elected presidents has hailed from a different ethnic group and region of the country. Both the NPP and the Republicans faced a reality check in their back-to-back electoral loses.

2. The NDC can win elections without the help of its founding father, former President J.J. Rawlings. This is the first election in which the charismatic and popular Rawlings, who ruled Ghana for almost two decades before handing over power in 2000, did not actively campaign for his party’s candidate. In fact, his wife, former first lady Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings, attempted to run for president on the ticket of the recently formed breakaway National Democratic Party, but her nominating papers were rejected by the Electoral Commission in October. Rawlings had supported his wife’s efforts, repeatedly expressing disappointment with the Mills-Mahama administration, then was absent from the NDC campaign trail. While Rawlings’ participation in NDC rallies probably would have added to Mahama’s margin of victory, the party won without his support.

3. The Nkrumah and Convention People’s Party (CPP) name brands are virtually irrelevant today. Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s anti-colonial leader and first president, undoubtedly is a hero to Ghanaians, but his glamorous daughter, Samia Nkrumah, failed to win re-election after one term in parliament and the present-day incarnation of the party he founded, the CPP, had its worst showing in a Ghanaian election, earning less than 1% of the vote. Moreover, the other presidential candidates (there were a total of eight) and small parties that claimed the Nkrumahist legacy all performed as poorly in the elections. The reason is most Ghanaians who identify with the Nkrumahist tradition vote NDC, and indeed Mahama proudly proclaims himself a Nkrumahist as did former president Mills. Despite the plethora of candidates and parties, no credible third parties exist, as Ghana has become a two-party democracy.

4. Ghanaians are strategic, informed citizens who voted “skirt and blouse.” In numerous constituencies across the country, the results were mixed, with one party securing the parliamentary seat and the other winning the presidential race. While the national map suggests an irrefutable NPP victory in the center of the country, namely in the Ashanti and Eastern regions, surrounded by the eight regions which voted NDC, a closer examination reveals some constituencies elected an NPP parliamentarian while giving the presidential vote to the NDC or vice versa. Local dynamics, such as the popularity of a particular candidate or generational conflicts over party primary results, led to these mixed results.

5. Despite the aforementioned pre-election polls, many so-called experts wrongly predicted an NPP victory. At an academic conference at a prominent midwestern university last month, for example, a political scientist bragged about her recent “de-briefing” of the new US ambassador to Ghana, confidently informing the diplomat that the NPP certainly would prevail in the elections based on insights from a Ghanaian academic. Yet, based in their university departments and think tanks in Ghana’s capital of Accra, as well as at European and American campuses, many of these political scientists often are clueless about “facts on the ground.” Surrounded by like-minded elites, it is not surprising Ghanaian democracy “experts” falsely think all Ghanaians will vote like them, but out in the countryside the story was different. Rural voters have witnessed practical, significant improvements in their lives over the past four years, ranging from newly-built school blocks to recently inaugurated electricity. These voters form the majority of the Ghanaian electorate and they voted solidly NDC.

6. Despite some glitches, Ghana remains a model democracy, not just for Africa but the world. Ghanaians may have to endure the NPP’s petty challenge to the results in the courts (doomed to failure as the Election Commission has won every case brought against it since 1992), but the elections were praised as free, fair, and well-run by local and foreign observers. Minor problems which arose, such as delayed starts at some polling stations, were quickly remedied by extending voting on Saturday, and the final results were declared about 24 hours later. Moreover, voter turnout was an impressive 80 percent. Contrast this efficiency and enthusiasm with American elections that are plagued by apathy, widely divergent registration and eligibility rules, and painfully slow vote counting particularly in the always inept battleground state of Florida. Who could forget Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe famous offer to send election observers to the US after the controversial 2000 Bush-Gore elections?

In the coming weeks and months, as the NPP surely abandons its fruitless challenge to the results and jockeying for leading the party in the 2012 elections commences, additional lessons will emerge, but the significance of this weekend’s elections for Ghana and the rest of Africa is immediately clear. At yesterday’s NDC victory rally, President Mahama pointed out that an entire generation of Ghanaians has grown up knowing no other system but democracy. And many of these young Ghanaians texted local vote counts to radio stations, followed the release of provisional results on the internet, and tweeted their reactions. In short, democracy is working in Ghana, despite the incredible challenges it faces like all underdeveloped nations in this capitalist world.

Finally, I have to comment on the blackout on Ghanaian elections in US media (most notably absent from television, including cable news): While Ghana’s elections did not make headlines–as they should, for some of the reasons outlined above–or barely even a mention, as they say “no news is good news.” It seems some American mainstream media only report on African elections when they see “tribal violence,” massive rigging, or power-sharing deals.

What was Dominique Strauss-Kahn wearing?

[image error]

Yesterday Nafissatou Diallo “agreed to settle” the civil lawsuit against prominent French politician Dominique Strauss-Kahn—she had accused him of sexual assault last year—for an undisclosed amount. Diallo has also settled a lawsuit against The New York Post. (The newspaper, without any evidence and citing “anonymous” sources, had reported that she worked as a prostitute.) After the settlement was announced, Diallo thanked the world and the skies, “I thank everybody, and I thank God.”

You know the story of Nafissatou Diallo already, and you know the story of the story, the ways in which much of the Western media, and in particular the U.S. and the French media, covered it. There’s no question who is the settler, that French guy, and who’s the native, “the African chambermaid.”

True to form, Reuters reported on Monday’s proceedings under the headline: “Strauss-Kahn, NYC hotel maid settle civil lawsuit over alleged assault.” The article names Strauss-Kahn four times, over the space of a sub-heading and three paragraphs, and names the judge in the case, Douglas McKeon, before whispering Nafissatou Diallo’s name. And here’s how Reuters introduces Nafissatou Diallo:

His accuser, Nafissatou Diallo, was present as the judge had ordered, wearing a green blouse with black pants and a gray and white scarf around her head.

Seriously? What matters is … what a woman wears? What do you think that French guy was wearing? Please, don’t answer.

The New York Times report isn’t much better, except that, thankfully, they don’t focus on wardrobe.

The AP mentions Diallo sort of quickly, in the second paragraph, and then can’t resist:

Strauss-Kahn did not attend the hearing on Monday at a Bronx courthouse. Diallo, her hair covered by a leopard-print scarf, looked composed and resolute as the deal was announced.

The Guardian as well mentions Diallo earlier, and then:

Dressed in a snow-leopard skin print headscarf and emerald blouse, she made no statement while in the courtroom. But in brief comments on the steps of the Bronx Supreme Court, Diallo, who was born in Guinea and who is the mother to a teenage girl, thanked her supporters.

The BBC actually mentioned Diallo in its second sentence, did not mention her clothing, and did end with this:

In the wake of Ms Diallo’s accusations, other women came forward with sexual assault allegations against him.

It’s worth noting that this miscoverage, a portmanteau that melds miscarriage and coverage, of this event is a fitting end to the International Human Rights Day and to the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender Violence.

First thoughts on Mali’s second coup

Mali’s interim Prime Minister—and NASA’s ex-interplanetary navigator—Cheikh Modibo Diarra was chased out of office Tuesday morning. He’d been arrested the night before by soldiers under the orders of Captain Amadou Haya Sanogo, the man who led the coup that set the country into a disastrous spiral of instability in March. Early Tuesday morning, in a terse and somber statement on national television (in French and in Bambara), Diarra gave up his post and took his government with him. What that means for Mali’s political future is anyone’s guess, but it doesn’t look good.

In the short term, not everyone will regret his precipitous departure. However, it hardly opens a path for greater stability. A long-shot candidate for president in the months before the coup, Diarra was named Prime Minister last spring in a deal forged between Sanogo’s junta and the organization of West African States (ECOWAS), in the person of President Blaise Campaoré of Burkina Faso. At the time, many—including me—considered his nomination a relatively judicious one. He’d done everything from selling handbags on New York’s Fifth Avenue to landing probes on Mars and piloting Microsoft Africa. Many Malians—in the diaspora at least—believed that he was not party to the corruption that had eaten away at the former government. He also had a certain amount of support from both prominent Muslim religious leaders and from the army itself (the latter via his father in law, ex-President and General Moussa Traoré, r. 1968-1991). The bloom on that rose faded fast, as Diarra endured intense criticism for being too close to both Sanogo and Campaoré. Over the last few months, however, Diarra had been working to put some daylight between himself and his erstwhile allies, notably by calling for rapid military intervention on the part of (some of) Mali’s neighbors, backed by outside powers. That position did not sit well with what’s left of the Malian army, which is firmly opposed to accepting any outside help. In the end, Diarra’s search for independence left him vulnerable.

The man had few allies, at home or abroad. He’d hardly made it back from Ouagadougou last April before he had alienated much of the political class by refusing to nominate many career politicians to the ministerial posts they felt they deserved. That position cost him both political capital and the counsel of more experienced actors, and he soon faced carping from the country’s perennial candidates that he was using the crisis as a power grab. By refusing to step aside as a candidate in the elections his government was charged with organizing, Diarra only fueled their fears. The prolonged absence of president Dioncounda Traoré—beaten nearly to death in the presidential palace by a mob—had left Diarra with some room for maneuver between April and August, when he had to begin to take a position on foreign intervention in the run-up to the U.N. General Assembly. Then and since, he’s called for Mali’s allies to act fast, and he surely knew that his own future was at stake, and that his former protectors would likely feel betrayed.

It wasn’t just Sanogo’s crew and the politicians who were displeased with him. French and American diplomats have considered him part of the problem for several months now. Whatever tentative support he once had from the international community has been drying up since at least June. Still, whatever one thought of Diarra’s track record, the sight of another civilian being hauled off by men in army uniforms is hardly reassuring. In the last few months, journalists, editors, and businesspeople have been the victims of such kidnappings, and the vicious assault on interim President Traoré—under the nose of the military—only underscored the fact that no one was safe. Arresting the Prime Minister represents just one step beyond what had become business as usual.

It’s a big step, and it will reverberate. One of the preconditions for any formal outside intervention in Mali has been political stability in the capital itself. The fragility of the situation there has just been exposed once again, and the national political convention that was to begin this week—at long last—has surely lost some of its meaning. Meanwhile, the resignation of Diarra and his team—assuming they follow him—risks making last week’s preliminary talks between rebel groups and the government moot. In other words, in terms of the occupation in the North, Mali’s latest coup sharply limits the possibilities for either intervention or negotiation, at least in the short term. It just might open up a third possibility—re-empowered, the Malian army, backed by ethnic militias and buoyed by popular sentiment, decides to go it alone, and soon, re-igniting a war it probably can not win. That would be one of the worst of a whole host of awful outcomes.

In short, it’s hard to imagine that a return to peace and security, North and South, is any closer with Diarra chased from power. His departure leaves President Traoré more isolated and exposed than ever, and raises the question of which angel might step in where Diarra once tred.

Note: these are preliminary thoughts on a story still unfolding. Here I’m calling it a coup d’état, but others might disagree and the Malian press I’ve seen hasn’t used that term.

December 10, 2012

Documentary: Fuelling Poverty in Nigeria

Kicking off with an introduction from Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, the short documentary Fuelling Poverty amounts to a very brief Nigerian Fuel Subsidy 101 course. In thirty minutes, it covers the history of the issue and methodically explains how the government (encouraged by the IFIs, by the way) failed its people. By removing the subsidy as it did, the government shocked the informal economy and made life more miserable for a huge segment of the population. Subsequent investigations into the complex workings of the subsidy regime revealed a massive corruption cover-up to the tune of US $7 billion annually.

Written by Ishaya Bako, produced by Oliver Aleogena, and funded by the Open Society Institute for West Africa, Fuelling Poverty looks good, sounds good, and says all the right things. Its interviews, featuring those affected by the subsidy removal and those that participated in Nigeria’s nationwide protests in January 2012, are affecting. The fuel subsidy was, as the film argues, the only real social spending the government did. Its removal cast a wide net.

The filmmakers hope to move the nation out of its current standstill, back toward action. “Nigerians need to hold government accountable and the way to do that is to organize,” they said at the film’s premiere at the Silverbird in Abuja last weekend. “The consequences of a docile public with the current challenges facing the country will be disastrous. This documentary, if well distributed, is going to trigger anger and demand for change. Our job is to manage that anger and make it a constructive force for social change.”

Cairo mosh pit

A few days ago Tom posted another installment of 10 African films to watch out for, one of which is the documentary “Underground/On the Surface,” on the popular “second-class” youth music genre mahragan shaabi. While we wait to see the documentary for ourselves next year, above and below are some home-made videos of young men dancing to these underground tunes on the streets (and in the internet cafés) of Egypt. It’s a great mash-up of b-boying, belly-dancing, house and the ever-popular mosh pit!

For our Arabic speakers, here is an episode of the Egyptian webshow 3ala Fein? produced by disalata.com’s online video magazine on Oka & Ortega. With their entire crew (shout out to Wezza!), they are called the “eight percent” (tamanya fil mya). These are the artists featured in the aforementioned trailer for “Underground/On the Surface,” and the following segment, which largely focuses on their music, explores the meanings behind their names and their music. (Ortega named himself literally after Argentinian footballer Ariel Ortega, it seems). “The eight percent” reflects the class consciousness within their political — though also humorous and sometimes lewd — music. Their music is made for the poorest classes in Egypt, the very spaces these young men come from:

Egypt’s 8 Percent: Mahragan Shaabi

A few days ago Tom posted another installment of 10 African films to watch out for, one of which is the documentary “Underground/On the Surface,” on the popular “second-class” youth music genre mahragan shaabi. While we wait to see the documentary for ourselves next year, above and below are some home-made videos of young men dancing to these underground tunes on the streets (and in the internet cafés) of Egypt. It’s a great mash-up of b-boying, belly-dancing, house and the ever-popular mosh pit!

For our Arabic speakers, here is an episode of the Egyptian webshow 3ala Fein? produced by disalata.com’s online video magazine on Oka & Ortega. With their entire crew (shout out to Wezza!), they are called the “eight percent” (tamanya fil mya). These are the artists featured in the aforementioned trailer for “Underground/On the Surface,” and the following segment, which largely focuses on their music, explores the meanings behind their names and their music. (Ortega named himself literally after Argentinian footballer Ariel Ortega, it seems). “The eight percent” reflects the class consciousness within their political — though also humorous and sometimes lewd — music. Their music is made for the poorest classes in Egypt, the very spaces these young men come from:

Jared Thorne’s Black Folks

Stencilled on the white walls of the Iziko Gallery ‘Annexe’ in Cape Town, a bell hooks quote from Black Looks: Race and Representation:

Stencilled on the white walls of the Iziko Gallery ‘Annexe’ in Cape Town, a bell hooks quote from Black Looks: Race and Representation:

For some time now the critical challenge for black folks has been to expand the discussion of race and representation beyond debates about good and bad imagery. Often what is thought to be good is merely a reaction against representations created by white people that were blatantly stereotypical. Currently, however, we are bombarded by black folks creating and marketing similar stereotypical images. It is not an issue of “us” and “them.” The issue is really one of standpoint. From what political perspective do we dream, look, create, and take action?

Hanging on the walls around the quote are, well, portraits of black people. At first glance that’s all it is. Pictures of black people, mostly against white backdrops looking melancholic. Representations of Cape Town’s self-made myth of the black middle class.

You might have heard that they don’t exist, and yet here they are, hanging off the walls, milling about the room with a glass of complementary wine (or tea) in their hands.

“When I moved from New York to Cape Town, I was surprised to see how middle class adaptation marries each other,” says Jared Thorne, the maker of the photographs. “There’s a common denominator. Some transcontinental dialogue between the black middle class the world over.”

“When I moved from New York to Cape Town, I was surprised to see how middle class adaptation marries each other,” says Jared Thorne, the maker of the photographs. “There’s a common denominator. Some transcontinental dialogue between the black middle class the world over.”

Thorne began shooting these portraits back when he was in the States. Upon moving to South Africa, he began to realise similarities in how the black middle class lives, and exploring the parallels. “Paramount to my research is how social class plays a significant role in defining how one witnesses Blackness.”

“There’s something adaptable about the black middle class. We can hang out in leafy suburbs in one moment, and in the hood in the next. We’re coded that way. And we switch to suit whatever situations we’re in easily.”

The people in the pictures all look slightly hardened. The walls behind them almost always bare. The surroundings are simple and minimal. As if they’re ready to pack and leave if ever the moment arises. As if they’re tired of straddling two worlds. As if they’re fighting to carve out an existence. With a foot in the door and suitcase in the corner.

The people in the pictures all look slightly hardened. The walls behind them almost always bare. The surroundings are simple and minimal. As if they’re ready to pack and leave if ever the moment arises. As if they’re tired of straddling two worlds. As if they’re fighting to carve out an existence. With a foot in the door and suitcase in the corner.

“The selection process was random. It was just young black folks I happened to meet. People who would let me into their houses. But they all looked like they were still navigating a space. Still trying to find certainty,” says Thorne.

But still, are they not just pictures of black people?

“It appears to be subtle work, but it’s less subtle if you know. Everything you need to know is there. The signifiers are embedded in the images. The gaze, the way they stand, how they furnish their apartments. It all speaks to the idea of the black middle class being transitory. It doesn’t look like anyone has been or is going to be there for a very long time. This wasn’t meant to be didactic though. I’m not claiming to have made anything anthropological here. But I am rethinking the archives. I’m putting black people in spaces they aren’t normally seen in.”

Thorne, ambitiously, wants to change the way history depicts black people. Tell a story that isn’t poverty porn, or ganglands gore, or activism. “I strongly believe that black people should create black content. What matters is the art’s historical context. Who reproduces? Who’s responsible for reconstructing the narrative?”

* Jared Thorne grew up in Boston, Massachusetts and has a Fine Arts Masters Degree from Columbia University. He lectures at Stellenbosch University and is a 2012 GIPCA fellow. The Black Folks exhibition runs until the 19th of January 2013, at the Iziko National Gallery Annexe.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers