Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 504

December 27, 2012

10 African Albums You Might Have Missed This Year

Kyle Shepherd (Photo by Ference Isaacs)

This list of 10 albums by African artists probably says more about my own musical preferences than it does about all those other “Best Albums of 2012″ year-end lists floating around on the web which didn’t include them (looking at you, Pitchfork, Stereogum, The FADER and SPIN). Not unlike last year, I’m surprised these albums don’t get more love on the net. My iTunes player tells me these were the recordings I’ve been listening to most this year — I got schooled while doing so too.

Jagwa Music – Bongo Heatheads

Jagwa Music – Bongo Heatheads

Quote: “Straight from Dar es Salaam, here’s Jagwa Music: a crew of 8 youngsters playing intricate grooves at breakneck speed on traditional & makeshift percussion, a keyboard player going wild on a battered vintage Casio, and three relentless front persons: two breathtaking, spectacular dancers & a charismatic lead vocalist/MC, belting out songs about survival in the urban maze, unfaithful lovers & voodoo.”

Watch and listen: Jagwa Music live in the streets of Dar. Janka Nabay & The Bubu Gang – En Yay Sah

Janka Nabay & The Bubu Gang – En Yay Sah

The similarities between the album cover art for Janka Nabay & The Bubu Gang and Jagwa’s are probably a coincidence but what both recordings do have in common is their drive. Sierra Leonean Janka Nabay and his American backing band delivered an awesome product.

Watch and listen: Somebody. Ben Zabo

Ben Zabo

Quote: “His music is a string of firecrackers igniting on the dance floor of a midnight party. It is a music that has been perfected in the loud, sweaty, open-air clubs that line the outskirts of Bamako, places where the competition to get heard is fierce, and the chances of moving upward and outward are next to none. / This album is the first album ever to be released by a Malian of Bo descent.”

Watch and listen: Sènsènbo. Sinkane

Sinkane

Quote: “New band of the day.”

For real though, Sudan-born Sinkane is Ahmed Gallab of Yeasayer (and many other bands).

Watch and listen: Runnin’. Youssoupha – Noir Désir

Youssoupha – Noir Désir

Youssoupha Mabiki is the son of Congolese legend Tabu Ley Rochereau.

Watch and listen: Les Disques de Mon Père (that’s “le père / the father,” 3:25 mins into the video).

Francophone African diaspora Hip-Hop speaking this much truth so eloquently — and so well-produced — about a nation’s ailing remains a rare thing. Kanyi – Lintombi Zifikile

Kanyi – Lintombi Zifikile

You know we admire South African rapper Kanyisa Mavi.

Watch (a 2011 video) and listen: Ingoma.

It’s tough, being a female MC out there. Kyle Shepherd – South African History !X

Kyle Shepherd – South African History !X

No other South African musician has been touring the world this year as widely as jazz artist Kyle Shepherd did. (Check his mad tour schedule; I’m still bummed he skipped his Belgian gig for a Swiss one.)

Quote: “paying homage to the languages of the first nation people…and bringing to the fore South Africa’s slave-holding past.”

Watch, listen, and take note: South African History !X. Ebo Taylor – Appia Kwa Bridge

Ebo Taylor – Appia Kwa Bridge

Quote: “Despite attending the same London music school as Fela Kuti in the early 1960s, this is only the second international release from Ghanaian highlife guitarist Ebo Taylor.”

Watch and listen: Ebo Taylor On Recording Appia Kwa Bridge. Francis Bebey – African Electronic Music 1975-1982

Francis Bebey – African Electronic Music 1975-1982

I wasn’t familiar with the work of late Cameroonian composer, musician, sculptor, novelist, guitarist, “Renaissance Man” and radio presenter Francis Bebey. Courtesy of French music label Born Bad.

Quote: “you’d be a fool to pass this up.”

Listen: Agatha. Karantamba – Ndigal

Karantamba – Ndigal

Teranga Beat released this extra-ordinary live recording (date: August 16, 1984; place: Sangomar Club, Thiès, Senegal) Gambian artist Bai Janha did with his last group, Karantamba, a school for young musicians.

Quote: “Band leader of the groups BLACK STAR, WHALES BAND, FABULOUS EAGLES & SUPREME EAGLES, founder of the group ALLIGATORS who later became the GUELEWAR, BAI is the one who created the unique psychedelic sound in the region of SENE-GAMBIA, mixing traditional compositions with Soul, his musical innovations contributed to the domination of AFRO-MANDING music in West Africa for more than a decade.”

Watch (older photo stills of the band) and listen: Satay Muso.

December 26, 2012

The Top 10 Music Videos of 2012

2012 is rapidly coming to a close, which means it’s time to assemble some of our favorite music videos from the past year. Indeed it’s no easy task to construct a video in which the moving picture finds a harmonious companion in the sonic beat. Just as daunting can be choosing, among the hundreds of videos we’ve been featuring over the past year in our weekly Music Break series, which ones succeeded most in carrying a spark of innovation, capturing the essence of a musical scene and astonishing us with visual splendor. However, we’re pleased with our final selections. So without any further delay, and in no particular order, here are 10 of our favorites:

If there was one video everyone seemed to approve of including on this list, it was the one above for Vetkuk vs Mahoota’s “iStokvela.” In the video, this expertly mixed South African kwaito track with a tinge of gospel transforms the streets into a dance floor showcase. Amidst the desaturated colors we encounter some sharp-sharp slow-motion mapantsula dancing (and a cameo from veteran kwaito producer Oskido).

Next up are the ‘Afro-punk collective’ Jagwa Music of Dar-es-Salaam. Here, they are performing the song “Heshima,” off their debut album Bongo Hotheads. These guys certainly know how to bring the party, we only wish we had been there to get down with them.

LV and Okmalumkoolkat (of the group Dirty Paraffin) came up with this video for their song “Sebenza” (meaning ‘work,’ in Zulu). We love the attention drifting subculture — which is huge in South Africa — gets here. The video was directed by photographer Chris Saunders, whose portfolio includes quality images of Johannesburg’s street style culture.

2012 was the year the Ghanaian Azonto conquered dance floors across the continent. It would be unthinkable if we didn’t include at least one Azonto video. In this case we chose a submission for a competition to select the best fan-produced video for Fuse ODG’s single “Antenna.” It features two dapper young men busting out their best Azonto moves in various locations around London.

2012 was also the year of “Gangnam Style.” Even though I’m sure we’re all a bit fatigued by PSY at this point and the song, we thought this Ivorian dance troupe’s version of the dance was at least moderately entertaining — their moves are certainly better than PSY’s:

Mozambican Dama Do Bling’s video for the song “Champion” is quirky and strangely captivating. There’s just something about watching friends competitively race tires in a pastel world while Dama Do Bling dances and bangs on barrels with her trademark sartorial panache.

Afrikaans rapper Jack Parow is a polarizing figure (though not quite as polarizing as the more well-known rap-rave group Die Antwoord). Personally, I find him to be pretty entertaining and his single “Afrikaans is Dood” (Afrikaans is Dead), was super catchy. Lucky for us, the video for the song is also a riot, with Mr. Parow fighting off a number tacky, sweatsuit-wearing thugs who are trying to steal his book of rhymes. The video was directed by Ari Kruger, who also came up with a great video for Driemanskap’s “Izulu Lelam” earlier this year.

Nigerian rapper D.i.s. Guise has blown up in recent months with his alluringly cosmic beats and solid rhymes. His videos are lo-fi done right and “Mr. Bambe” is no exception. Watch him get lyrical about all things Bambe in capriciously shifting disguise. (And don’t miss out on his free mixtape.)

London-based The Busy Twist’s “Friday Night” will have you dancing in your seat and the video, which was filmed in Ghana, provides you with a healthy reminder of the sheer pleasure derived from ordinary dance.

And lastly this video from the Nigerian-born, French singer Asa (who has a habit of putting out high quality videos — remember her “Be My Man”, or more recently, “Ba Mi Dele”). The haunting video for her song “The Way I Feel” gives Asa a platform to lay her jazzy vocals over immaculately constructed scenes reminiscent of melancholic documentary photographs in times of war.

The Top 10 African Music Videos of 2012

2012 is rapidly coming to a close, which means it’s time to assemble some of our favorite music videos from the past year. Indeed it’s no easy task to construct a video in which the moving picture finds a harmonious companion in the sonic beat. Just as daunting can be choosing, among the hundreds of videos we’ve been featuring over the past year in our weekly Music Break series, which ones succeeded most in carrying a spark of innovation, capturing the essence of a musical scene and astonishing us with visual splendor. However, we’re pleased with our final selections. So without any further delay, and in no particular order, here are 10 of our favorites:

If there was one video everyone seemed to approve of including on this list, it was the one above for Vetkuk vs Mahoota’s “iStokvela.” In the video, this expertly mixed South African kwaito track with a tinge of gospel transforms the streets into a dance floor showcase. Amidst the desaturated colors we encounter some sharp-sharp slow-motion mapantsula dancing (and a cameo from veteran kwaito producer Oskido).

Next up are the ‘Afro-punk collective’ Jagwa Music of Dar-es-Salaam. Here, they are performing the song “Heshima,” off their debut album Bongo Hotheads. These guys certainly know how to bring the party, we only wish we had been there to get down with them.

LV and Okmalumkoolkat (of the group Dirty Paraffin) came up with this video for their song “Sebenza” (meaning ‘work,’ in Zulu). We love the attention drifting subculture — which is huge in South Africa — gets here. The video was directed by photographer Chris Saunders, whose portfolio includes quality images of Johannesburg’s street style culture.

2012 was the year the Ghanaian Azonto conquered dance floors across the continent. It would be unthinkable if we didn’t include at least one Azonto video. In this case we chose a submission for a competition to select the best fan-produced video for Fuse ODG’s single “Antenna.” It features two dapper young men busting out their best Azonto moves in various locations around London.

2012 was also the year of “Gangnam Style.” Even though I’m sure we’re all a bit fatigued by PSY at this point and the song, we thought this Ivorian dance troupe’s version of the dance was at least moderately entertaining — their moves are certainly better than PSY’s:

Mozambican Dama Do Bling’s video for the song “Champion” is quirky and strangely captivating. There’s just something about watching friends competitively race tires in a pastel world while Dama Do Bling dances and bangs on barrels with her trademark sartorial panache.

Afrikaans rapper Jack Parow is a polarizing figure (though not quite as polarizing as the more well-known rap-rave group Die Antwoord). Personally, I find him to be pretty entertaining and his single “Afrikaans is Dood” (Afrikaans is Dead), was super catchy. Lucky for us, the video for the song is also a riot, with Mr. Parow fighting off a number tacky, sweatsuit-wearing thugs who are trying to steal his book of rhymes. The video was directed by Ari Kruger, who also came up with a great video for Driemanskap’s “Izulu Lelam” earlier this year.

Nigerian rapper D.i.s. Guise has blown up in recent months with his alluringly cosmic beats and solid rhymes. His videos are lo-fi done right and “Mr. Bambe” is no exception. Watch him get lyrical about all things Bambe in capriciously shifting disguise. (And don’t miss out on his free mixtape.)

London-based The Busy Twist’s “Friday Night” will have you dancing in your seat and the video, which was filmed in Ghana, provides you with a healthy reminder of the sheer pleasure derived from ordinary dance.

And lastly this video from the Nigerian-born, French singer Asa (who has a habit of putting out high quality videos — remember her “Be My Man”, or more recently, “Ba Mi Dele”). The haunting video for her song “The Way I Feel” gives Asa a platform to lay her jazzy vocals over immaculately constructed scenes reminiscent of melancholic documentary photographs in times of war.

December 24, 2012

Consuming Africa (at Christmas Time)

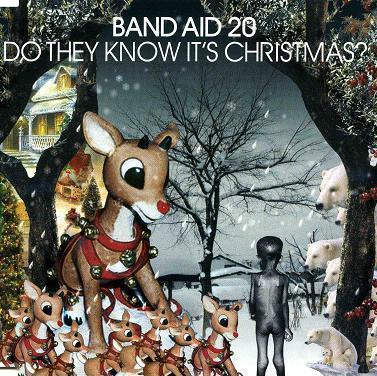

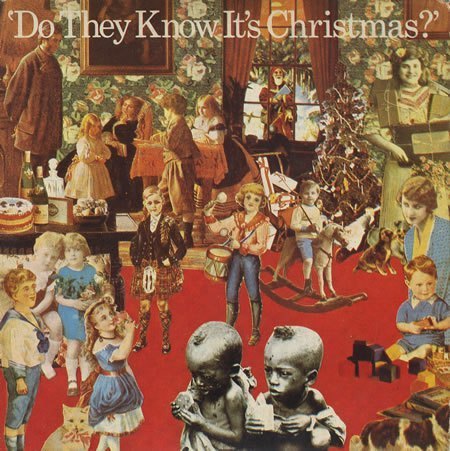

In 2004, the British press reported that the album cover Damien Hirst had designed for Band Aid 20’s re-recording of the 1984 single “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” had been rejected by the organizers, for fear it would frighten small children. “The record, that’s the important part,” explained Midge Ure. “The cover doesn’t really matter. Throw the cover away. Buying it is the important thing.”

In 2004, the British press reported that the album cover Damien Hirst had designed for Band Aid 20’s re-recording of the 1984 single “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” had been rejected by the organizers, for fear it would frighten small children. “The record, that’s the important part,” explained Midge Ure. “The cover doesn’t really matter. Throw the cover away. Buying it is the important thing.”

Hirst had depicted an emaciated black child perched on the Grim Reaper’s knee, while on the other side of the album a white child cradled in Santa’s lap clutched wads of banknotes. There was a sense that this particular juxtaposition could be considered distasteful, but the reason that got around was that the kids would be scared. An alternative cover arrived, in which an emaciated black-and-white black child walks naked through the snow into a full-color fairytale landscape, menaced on either side by a herd of outsized cartoon reindeer and a large family of hungry looking polar bears. Hirst’s excessively disturbing double image had been replaced by what was plainly a playful riff on “Vulture stalking a child,” the world-famous photograph of a Sudanese girl taken in 1993 by South African photographer Kevin Carter, who committed suicide months after the image was awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

The child on the new album cover was copy-pasted from Live Aid’s 1985 promotional material, where it had been placed beneath the Africa-shaped guitar. On the concert program the child was positioned beside the words “Global Juke Box.” Much like Bono’s line, “Tonight, thank God it’s them instead of you,” the image had somehow survived the intervening nineteen years and journeyed for a thousand miles across the Ethiopia-Sudan border and due west into Darfur. Just as it had in 1985, the child on the 2004 cover faces away from the camera. What we see is a frame wasted to the proportions of a semi-silhouette, slim shoulder-blades jutting, fleshless legs knocking at the knees. We don’t know whether or not this is one of the two black-and-white black children that appear huddled near Alice in Wonderland and the Cheshire Cat in the foreground of the rosy-cheeked Edwardian nursery idyll Sir Peter Blake designed for the original cover of “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” in 1984, but the question is nonetheless worth asking.

In her 1963 book On Revolution Hannah Arendt argued that compassion, “by its very nature cannot be touched off by the sufferings of a whole class or a people, or, least of all, mankind as a whole [...] Because compassion abolishes the distance, the worldly space between men where politics matters, the whole realm of human affairs, are located, it remains, politically speaking, irrelevant and without consequence.” Arendt wrote compassion as a fantasy of intimacy, a response to clear delineations of personality. It was an imaginative remapping of the world in shrunken dimensions, with politics, distance, and perhaps difference too, wrung out. The previous year she had seen Adolf Eichmann defend himself as a dutiful Kantian, only to be found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced, by the state of Israel, to death. She had coined the much-quoted expression “banality of evil” to describe the practice of non-thinking, the failure of those such as Eichmann to reflect on their crimes as they performed them.

In her 1963 book On Revolution Hannah Arendt argued that compassion, “by its very nature cannot be touched off by the sufferings of a whole class or a people, or, least of all, mankind as a whole [...] Because compassion abolishes the distance, the worldly space between men where politics matters, the whole realm of human affairs, are located, it remains, politically speaking, irrelevant and without consequence.” Arendt wrote compassion as a fantasy of intimacy, a response to clear delineations of personality. It was an imaginative remapping of the world in shrunken dimensions, with politics, distance, and perhaps difference too, wrung out. The previous year she had seen Adolf Eichmann defend himself as a dutiful Kantian, only to be found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced, by the state of Israel, to death. She had coined the much-quoted expression “banality of evil” to describe the practice of non-thinking, the failure of those such as Eichmann to reflect on their crimes as they performed them.

Of the many t-shirt wearing supergroups that dominated popular late twentieth-century expressions of global conscience in the West, the loudest were those organised around the problem of famine. (Willie Nelson’s Farm Aid and Steven Van Zandt’s Artists Against Apartheid, both founded in 1985, were the major exceptions.) Wildly grandiose projects, such as “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” (very white, very male, very shouty), Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie’s retort “We Are the World,” and the Canadian anthem “Tears Are Not Enough,” were attempts to rewrite compassion as a totalising form of largely content-free politics, confident avowals of Euro-American messianism made just a few years before Francis Fukuyama would pronounce the end of History.

“We’re saving our own lives,” sung Bob Dylan. “It’s true we’ll make a better day / Just you and me.”

“We can bridge the distance, / Only we can make the difference,” replied Bryan Adams.

The widest possible constituencies were appealed to – “the world,” “Africa,” “the children,” “them,” “us,” “the other ones,” “people dying,” “God’s great big family,” and so on. The music videos did not show images of people suffering in East African famines, but rather musicians and their lustrous, screen-filling hairstyles crowded together in studios in Notting Hill and on Beverly Boulevard. Stevie Wonder dueted with Bruce Springsteen. These were objects of fascination, not sympathy. Still, Arendt’s “worldly space between men where politics matters” took a battering. “We,” it was claimed, were “the world,” a world obliged to “come together as one.” In the British version, the world was small enough that you could feasibly throw your arms around it (“at Christmas time”). Appropriate to a nation forever astounded by its own rather temperate meteorological conditions, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” offered a Pan-African weather forecast of the most severe pessimism: “there won’t be snow in Africa this Christmas time / The greatest gift they’ll get this year is life / Where nothing ever grows, no rain or rivers flow / Do they know it’s Christmas time at all?” The Band Aid slogan “Feed the World” was accompanied by an illustration of a two dimensional globe placed like a dinner-plate between a knife and fork. This didn’t make sense. It confused giving with consuming, and implied that you should in fact eat the world, and particularly the T-bone steak continent of Africa. But who was to quibble over such details?

If these songs were an invitation to compassion, the surprise was that this invitation was made in the most abstract of idioms. If we were to reflect on suffering and inequality, we preferred to look at our rockstars while doing it. Everyone already knew what famine sufferers looked like, and nobody contested the gravity of the food crisis in the Horn of Africa, and so the appeal could provoke a compassionate response while remaining wonderfully impersonal. Except that, in the British case, back crept the icon of the starved black-and-white black infant, back from Biafra, and from the TV reports of the BBC’s Michael Buerk, and into abrupt conjunction with the sounds and symbols of Western pop. On album covers and concert posters, in other words at the point of sale, the image of the black-and-white black child still could not be dispensed with in 2004.

If these songs were an invitation to compassion, the surprise was that this invitation was made in the most abstract of idioms. If we were to reflect on suffering and inequality, we preferred to look at our rockstars while doing it. Everyone already knew what famine sufferers looked like, and nobody contested the gravity of the food crisis in the Horn of Africa, and so the appeal could provoke a compassionate response while remaining wonderfully impersonal. Except that, in the British case, back crept the icon of the starved black-and-white black infant, back from Biafra, and from the TV reports of the BBC’s Michael Buerk, and into abrupt conjunction with the sounds and symbols of Western pop. On album covers and concert posters, in other words at the point of sale, the image of the black-and-white black child still could not be dispensed with in 2004.

*

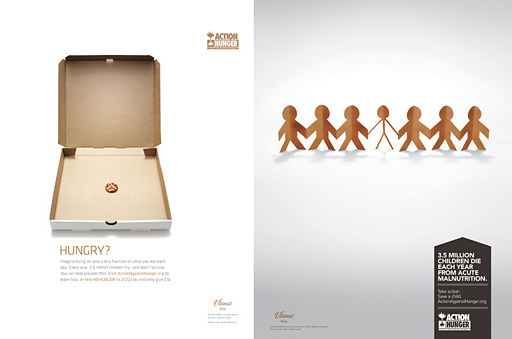

Disaster porn has been for many years the dominant style of humanitarian appeals for popular responses to famine. What kind of images can possibly fill in for the altogether enthralling scene of non-white bodies wracked with overwhelming pain, images which, however consistently raced and placed, claim to express nothing but pure need? The ad campaign launched by Action Against Hunger late last year, marked a significant shift in this regard.

As good students of Donald Draper, we all know that advertising is based on one thing: happiness. According to Don this entails at least three things: smelling the interior of a new car, freedom from fear, and a billboard on the side of the road that screams with reassurance that whatever you’re doing is okay. Which is all very well, provided an ad follows the underlying logic of advertising: lying to people to make us want something we don’t really need.

But with humanitarian advertising something strange happens. It would appear that when humanitarian groups solicit money from consumers of mass media an altogether different transaction is being proposed, namely one in which an advertiser tells the truth and compels people to hand over surplus cash so that the real and urgent needs of others can be met. At least, that’s something like how it should go. Trouble is, the old consumer mentality dies very hard, and the two modes of advertising are all jumbled up. There aren’t two different kinds of advertising space, one for commercial ads and another for humanitarian appeals: a billboard is a billboard. (This is one reason why self-evidently anti-humanitarian companies like BP, ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, Dow Chemical and others have lately gone to such conspicuous lengths to try to convince everybody that they’re actually much more like groups such as Greenpeace, or Medecins Sans Frontieres, or the Disasters Emergency Committee, than they are like the sort of oil-spilling, icecap-melting, Iraq-invasion-lobbying, Bhopal-poisoning, Saro-Wiwa-murdering transnational shysters that we might otherwise have quite innocently supposed them to be.)

![[OILADS]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1419465860i/13073482._SX540_.jpg) In any case, the suspicion has long lurked that gawping at pictures of starving children in Africa might have somehow crossed over into the Don Draper realm of advertising, and become a source of happiness for the kindly Western reader. In fundraising campaigns from the Biafran war onwards it became clear that the most effective way of raising money for starving (almost always African) populations was also the way that luxuriated in the vulnerability of the hungry, that enjoyed not only Western power to save but Western power per se. Those who have come to the conclusion that weaving images of some of the world’s most vulnerable people into our ever brasher, crasser mediascape is not okay will have welcomed the recent move away from such shock tactics. But what is the face of hunger advertising that has at last decided not to show a face?

In any case, the suspicion has long lurked that gawping at pictures of starving children in Africa might have somehow crossed over into the Don Draper realm of advertising, and become a source of happiness for the kindly Western reader. In fundraising campaigns from the Biafran war onwards it became clear that the most effective way of raising money for starving (almost always African) populations was also the way that luxuriated in the vulnerability of the hungry, that enjoyed not only Western power to save but Western power per se. Those who have come to the conclusion that weaving images of some of the world’s most vulnerable people into our ever brasher, crasser mediascape is not okay will have welcomed the recent move away from such shock tactics. But what is the face of hunger advertising that has at last decided not to show a face?

As you might expect, there’s nobody in Action Against Hunger’s 2011 ads. Nobody black, nobody brown, nobody at all. Instead there’s a tiny pepperoni pizza in a yawning pizza-box, and a string of seven (light brown) paper dolls, one of which is very thin. No jutting ribs or flies around the eyes, this is hunger imagined in a slimmed-down version of the universal symbol for the men’s bathroom, and “universal” is indeed the buzzword the ad company returned to when explaining the ad.

There’s no arid Horn of Africa background, no crumbling shacks or parched soil. We’re dealing with what Action Against Hunger describe as “abstract imagery,” and these days that can only mean a plain white background and some tasteful drop-shadows. How did the food crisis in the Sahel end up being represented by Western humanitarian organizations through the visual idiom of the MacBook Pro? It’s the aesthetics of absence, which Band Aid had flirted with, an aesthetics enabled, surely, by the knowledge that representations of the starving have for a long time been so utterly colloquialised as to make their repetition dull, superfluous, a kind of visual tautology. The “copy” on the ads is shorn of racial and national identifiers, and the emergency is conceived of as a norm graspable in steady annual figures, the bureaucratic vocabulary par excellence: “3.5 million children die each year from acute malnutrition. Take action. Save a child.”

There are at least two weird things about the ads. The first is the pizza: a miniscule aperitif drowning in a sea of cardboard packaging, the kind of meagre repast we’ll all have to make do with when Herman Cain is sworn in come 2016. The war on peckishness. The pizza was attacked by Paul Light, a politics professor at NYU, who wanted the ad “redesigned to focus on good food, not what many givers would see as a very unhealthy option.” Light was concerned that people may mistakenly suppose that Action Against Hunger is a lobbying group for more and bigger pizzas.

There are at least two weird things about the ads. The first is the pizza: a miniscule aperitif drowning in a sea of cardboard packaging, the kind of meagre repast we’ll all have to make do with when Herman Cain is sworn in come 2016. The war on peckishness. The pizza was attacked by Paul Light, a politics professor at NYU, who wanted the ad “redesigned to focus on good food, not what many givers would see as a very unhealthy option.” Light was concerned that people may mistakenly suppose that Action Against Hunger is a lobbying group for more and bigger pizzas.

The second weird thing is that the whole appeal is sponsored by Ultimat Vodka (slogan: “Live Ultimately”), whose logo appears in the bottom corner of each ad and which professes to be “tired” of hunger. And it’s at this point, as we think about millions of acutely malnourished children, and then of a pizza the size of cookie, and then of a luxury Polish vodka made from both grains and potatoes, that we might feel compelled to wonder, like a character in a J.G. Ballard novel: “What sort of scenario is the mind quietly stitching together?”

There has been a shift since 1985. Then, the target was a mass TV audience and Bono’s job was to construct a collective ethical subject for primetime and then cajole it to respond in some way to famine in faraway places. Since then, that audience has been dispersed across multiple platforms and media, and a series of neoliberal governments have overseen a reallocation of wealth which means that nowadays the buying power of most philanthropic consumers has diminished significantly. If the image of the starving black child has been deemed obsolete, then so has the Western “we” that claimed so much power for itself in the late 1980s. Why bother singing to the proles today? Better to flatter with clean lines and smart-sounding data those high-end consumers who, for a long time, have been only too pleased to submerge intellectual or moral thinking beneath a managerial practice which welcomes the humanitarian appeal as one more opportunity to congratulate itself on having moved beyond the political.

Bono has been an exact bellwether for these changes. Plainly still desiring nothing more than to throw another huge concert, he rightly suspects that nobody could bear to watch such a thing, and so has contented himself with running a private company, the impossibly pretentious “(PRODUCT)RED,” which siphons off a meagre trickle of the profits generated by major corporations such as Gap, Apple, American Express, and Starbucks into the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. As always, Bono brings his own particular poetics of stupidity to his task. It was “Thank God it’s them instead of you,” in 1985. And now? “I’m Inspi(red).”

A version of this article, (itself an elaboration on a previous post on AIAC,) appeared in the recent “Feast and Famine” edition of The New Inquiry.

The Top 10 Films of 2012

As always, end of year lists are met with anticipation; either by those eager to see the year in review, or by critics ready to decry what has been left off. No list is definitive, so please do add your suggestions and comments below. For me, it has been an explosive year of African cinema; from the astronomic rise of interest in African sci-fi (forgive the pun), to big-budget films getting the well-deserved attention of the European distribution market, incredibly powerful and moving activist filmmaking that has documented the shifting politics of the continent, to the wild and wonderful experimenters. Here, I’ve tried to honour a range of filmmaking styles and genres, all of which blew my socks off.

As always, end of year lists are met with anticipation; either by those eager to see the year in review, or by critics ready to decry what has been left off. No list is definitive, so please do add your suggestions and comments below. For me, it has been an explosive year of African cinema; from the astronomic rise of interest in African sci-fi (forgive the pun), to big-budget films getting the well-deserved attention of the European distribution market, incredibly powerful and moving activist filmmaking that has documented the shifting politics of the continent, to the wild and wonderful experimenters. Here, I’ve tried to honour a range of filmmaking styles and genres, all of which blew my socks off.

Nairobi Half Life (Kenya)

This, the first feature film by Kenyan director David ‘Tosh’ Gitonga, is a warm, sharp film that captures its subject — Nairobi — with a witty knowingness, but also, with a rare reverence. The sprawling, dark, dangerous city of Nairobi is infamous, we’re all familiar with its not-so-clever nickname, ‘Nairobbery’. But, as with every city, it has another side — a vital, energetic, creative and exciting side that attracts young people from all over Kenya. Gitonga’s film is as much about the well-traversed journey from rural to urban in contemporary Africa, as about the difficulties of growing up and becoming a ‘man’, whatever that might mean. Beautifully shot with an excellent soundtrack, Nairobi Half Life is an exciting first feature, and subsequently is getting a lot of hype across Kenya, and in Europe too.

Dear Mandela (South Africa)

As newspapers scramble to find their Mandela obituaries in the light of another stint of ill-health from the former President, this film by Dara Kell and Christopher Nizza is perhaps all the more timely, and painful. For it asks, what has come of the promises the ANC made to the young generation in 1994?

In the case of Abahlali baseMjondolo, a group of activists fighting for their right to stay in temporary settlements without the fear of eviction and violence, the promises have been continually broken. The film is a moving testament to the power of grass-roots political organisations, who source the tools and knowledge they need to take their cause to the highest level: “They think we don’t know the law. They don’t think we know the constitution. You can’t evict people like us. We know.”

But this isn’t just a straight-up documentary. There are beautiful, kaleidoscopic moments in the film that use more experimental means to capture what it means to be a part of a community; visually, the filmmakers tentatively point to the bonds that the shack-dwellers share through an inventiveness of visual style. You can read my full review here.

The Curse (Morocco)

Oh, the tyranny of children. This incredible short film by Fyzal Boulifa is a haunting tale of young female sexuality wounded and bullied by the oppressive society around her. In rural Morocco, a young woman and her lover meet in a rubble-filled ditch. Spotted by an eagle-eyed bunch of children, she is harassed by her young tormentors all the way home. Haunting and harsh, the narrative reflects the inhospitable sharpness of the landscape that surrounds the young girl. This is short filmmaking at its best.

Boulifa won the Premier Prix Illy for Short Filmmaking at this year’s Cannes Directors’ Fortnight, and has gone on to win a slew of other awards since. We can expect great things from him in the future…

When China Met Africa (UK)

How are the political and economic plates shifting beneath us as we move further into the 21st century? When China Met Africa focuses on the tales of a few individuals, whose work in on the African continent signifies the shifting tectonic plates of global alliances and interests.

Jonathan Duncan wrote a review of the film here. “By avoiding academic abstractions such as: neo-colonialism, geopolitics and paradigmatic shifts in economic power, the success of Marc and Nick Francis’s latest observational documentary ‘ unravels by undercutting these heightened contexts. They circumvent the clamor of voices participating in the discussion of China’s co-authorship in Africa, and instead refurbish the story by taking us straight to the ground.”

The films of the Mosireen Collective (Egypt)

In 2012, no group of filmmakers made such an impact on me as Mosireen; the defiant, relentless collective who started filming the Egyptian revolution, and who now document political struggles and movements across the country. They use cinema as a tool for change, and for self-reflection. Their Tahrir Square open cinema brings films to the public, while their huge YouTube channel is an impressive revolutionary archive. Engaged, embedded and determined, they are an incredible testament to the power that collective filmmaking can have in our contemporary moment.

Kempinski (Mali)

This film actually came out in 2007, however I include it here as a nod to the surge of critical discussion around African sci-fi in 2012. Remember the exhibition titled Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction at the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol, UK; the screenings at Africa Utopia at The Southbank Centre in London; and the deserved praise for Wanuri Kahiu’s Pumzi. Science fiction films from the African continent have been celebrated this year, as a means of subverting and refracting narratives about Africa, both as a mythical unit and as a challenge to the various entrenched beliefs that Africa will always be ‘behind’ compared to the techno-rabid West.

Kempinski is a simple but effective conceit: in a neon-lit unidentified jungle, Africans speak of the future in the present tense. It is a simple feedback loop, a ‘back to the future’, where the future has already gone to seed. Neil Beloufa’s work is eery, but sharp. This film, in many ways, demonstrates why sci-fi is an interesting tool with which to think, and talk, about Africa and our myths about it.

The 9 Muses (UK)

Fusing archival footage and stunning contemporary shots, this film by John Akomfrah (of the Black Audio Film Collective) is a patient, considered submersion into the history of migration, told through excerpts from literature — Paradise Lost, The Odyssey, Richard II, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, Beckett’s Molloy and Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood — and through testimony of those who made the journey from the heat of the South, to the cold, industrial North. It is poetic, labyrinthine; it excavates the history of cinema as much as its subject; mining black histories, home-making and race by considering images, myths and literary tropes as part of the founding histories and mythologies of human movement.

Tey (Senegal)

I waited a long time to see this film. It was lauded at Cannes and the Berlinale before it finally came to the London Film Festival (and Film Africa). But what I finally saw far surpassed my expectations. Satché, played by Saul Williams, is the walking dead (almost literally). He is living his last day on earth. His day begins at his own funeral wake, except he’s awake. He walks through his unnamed town, and people flock to celebrate his life, at him, with him. Later, his uncle performs the burial rites on his still-living body. It is a cross between everyone’s vain fantasy — to be hovering above their own funeral, seeing how much they were really loved — and a poetic musing on life and mortality.

Shot in rich colours, in turns delicate and elegiac then strong and frenetic — as any last day on earth would surely be — Gomis captures all of life in a day. A must see for any auteur film lovers out there. Read Jonathan Duncan’s full review here.

Otelo Burning (South Africa)

The director of the South African hit documentary Surfing Soweto, has returned to surfing with this, her first feature fiction — Otelo Burning. However, the surfing is no longer on top of railway trains into Johannesburg, or dancing off the sides of train-cars returning back to the townships; dusty, electrified and full of impending doom. No, Otelo Burning is about surfing the waves that crash against the South African coast, at a time when apartheid was crumbling, and when young black men and women were facing an apocalypse. No less about defining the self against the harsh and ignorant views of others (exactly as disenfranchised and forgotten youths in Surfing Soweto were), Otelo Burning is lush, sexy, complex and gripping, accompanied by an outrageously cool soundtrack. A must see.

Cursed Be The Phosphate (Tunisia)

And finally, Tunisian filmmaker Sami Tlili’s Cursed Be The Phosphate, which tells the story of the 2008 revolts in the Gafsa mining basin, and more particularly in the town of Redayef. Tlili’s suggestion that these protests were an important precursor to the country’s 2011 Revolution sounded and looked very convincing.

* Deserving mention are also Coming Forth By Day, the long-awaited film by Egyptian writer-director Hala Lotfy; and the harrowing documentary Call Me Kuchu (doc) by Malika Zouhali-Worrall and Katherine Fairfax Wright.

Here’s to 2013.

The Top 10 African Films of 2012

As always, end of year lists are met with anticipation; either by those eager to see the year in review, or by critics ready to decry what has been left off. No list is definitive, so please do add your suggestions and comments below. For me, it has been an explosive year of African cinema; from the astronomic rise of interest in African sci-fi (forgive the pun), to big-budget films getting the well-deserved attention of the European distribution market, incredibly powerful and moving activist filmmaking that has documented the shifting politics of the continent, to the wild and wonderful experimenters. Here, I’ve tried to honour a range of filmmaking styles and genres, all of which blew my socks off.

As always, end of year lists are met with anticipation; either by those eager to see the year in review, or by critics ready to decry what has been left off. No list is definitive, so please do add your suggestions and comments below. For me, it has been an explosive year of African cinema; from the astronomic rise of interest in African sci-fi (forgive the pun), to big-budget films getting the well-deserved attention of the European distribution market, incredibly powerful and moving activist filmmaking that has documented the shifting politics of the continent, to the wild and wonderful experimenters. Here, I’ve tried to honour a range of filmmaking styles and genres, all of which blew my socks off.

Nairobi Half Life (Kenya)

This, the first feature film by Kenyan director David ‘Tosh’ Gitonga, is a warm, sharp, witty film that captures its subject — Nairobi — with a witty knowingness, but also, with a rare reverence. The sprawling, dark, dangerous city of Nairobi is infamous, we’re all familiar with its not-so-clever nickname, ‘Nairobbery’. But, as with every city, it has another side — a vital, energetic, creative and exciting side that attracts young people from all over Kenya. Gitonga’s film is as much about the well-traversed journey from rural to urban in contemporary Africa, as about the difficulties of growing up and becoming a ‘man’, whatever that might mean. Beautifully shot with an excellent soundtrack, Nairobi Half Life is an exciting first feature, and subsequently is getting a lot of hype across Kenya, and in Europe too.

Dear Mandela (South Africa)

As newspapers scramble to find their Mandela obituaries in the light of another stint of ill-health from the former President, this film by Dara Kell and Christopher Nizza is perhaps all the more timely, and painful. For it asks, what has come of the promises the ANC made to the young generation in 1994?

In the case of Abahlali baseMjondolo, a group of activists fighting for their right to stay in temporary settlements without the fear of eviction and violence, the promises have been continually broken. The film is a moving testament to the power of grass-roots political organisations, who source the tools and knowledge they need to take their cause to the highest level: “They think we don’t know the law. They don’t think we know the constitution. You can’t evict people like us. We know.”

But this isn’t just a straight-up documentary. There are beautiful, kaleidoscopic moments in the film that use more experimental means to capture what it means to be a part of a community; visually, the filmmakers tentatively point to the bonds that the shack-dwellers share through an inventiveness of visual style. You can read my full review here.

The Curse (Morocco)

Oh, the tyranny of children. This incredible short film by Fyzal Boulifa is a haunting tale of young female sexuality wounded and bullied by the oppressive society around her. In rural Morocco, a young woman and her lover meet in a rubble-filled ditch. Spotted by an eagle-eyed bunch of children, she is harassed by her young tormentors all the way home. Haunting and harsh, the narrative reflects the inhospitable sharpness of the landscape that surrounds the young girl. This is short filmmaking at its best.

Boulifa won the Premier Prix Illy for Short Filmmaking at this year’s Cannes Directors’ Fortnight, and has gone on to win a slew of other awards since. We can expect great things from him in the future…

When China Met Africa (UK)

How are the political and economic plates shifting beneath us as we move further into the 21st century? When China Met Africa focuses on the tales of a few individuals, whose work in on the African continent signifies the shifting tectonic plates of global alliances and interests.

Jonathan Duncan wrote a review of the film here. “By avoiding academic abstractions such as: neo-colonialism, geopolitics and paradigmatic shifts in economic power, the success of Marc and Nick Francis’s latest observational documentary ‘ unravels by undercutting these heightened contexts. They circumvent the clamor of voices participating in the discussion of China’s co-authorship in Africa, and instead refurbish the story by taking us straight to the ground.”

The films of the Mosireen Collective (Egypt)

In 2012, no group of filmmakers made such an impact on me as Mosireen; the defiant, relentless collective who started filming the Egyptian revolution, and who now document political struggles and movements across the country. They use cinema as a tool for change, and for self-reflection. Their Tahrir Square open cinema brings films to the public, while their huge YouTube channel is an impressive revolutionary archive. Engaged, embedded and determined, they are an incredible testament to the power that collective filmmaking can have in our contemporary moment.

Kempinski (Mali)

This film actually came out in 2007, however I include it here as a nod to the surge of critical discussion around African sci-fi in 2012. Remember the exhibition titled Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction at the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol, UK; the screenings at Africa Utopia at The Southbank Centre in London; and the deserved praise for Wanuri Kahiu’s Pumzi. Science fiction films from the African continent have been celebrated this year, as a means of subverting and refracting narratives about Africa, both as a mythical unit and as a challenge to the various entrenched beliefs that Africa will always be ‘behind’ compared to the techno-rabid West.

Kempinski is a simple but effective conceit: in a neon-lit unidentified jungle, Africans speak of the future in the present tense. It is a simple feedback loop, a ‘back to the future’, where the future has already gone to seed. Neil Beloufa’s work is eery, but sharp. This film, in many ways, demonstrates why sci-fi is an interesting tool with which to think, and talk, about Africa and our myths about it.

The 9 Muses (UK)

Fusing archival footage and stunning contemporary shots, this film by John Akomfrah (of the Black Audio Film Collective) is a patient, considered submersion into the history of migration, told through excerpts from literature — Paradise Lost, The Odyssey, Richard II, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, Beckett’s Molloy and Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood — and through testimony of those who made the journey from the heat of the South, to the cold, industrial North. It is poetic, labyrinthine; it excavates the history of cinema as much as its subject; mining black histories, home-making and race by considering images, myths and literary tropes as part of the founding histories and mythologies of human movement.

Tey (Senegal)

I waited a long time to see this film. It was lauded at Cannes and the Berlinale before it finally came to the London Film Festival (and Film Africa). But what I finally saw far surpassed my expectations. Satché, played by Saul Williams, is the walking dead (almost literally). He is living his last day on earth. His day begins at his own funeral wake, except he’s awake. He walks through his unnamed town, and people flock to celebrate his life, at him, with him. Later, his uncle performs the burial rites on his still-living body. It is a cross between everyone’s vain fantasy — to be hovering above their own funeral, seeing how much they were really loved — and a poetic musing on life and mortality.

Shot in rich colours, in turns delicate and elegiac then strong and frenetic — as any last day on earth would surely be — Gomis captures all of life in a day. A must see for any auteur film lovers out there. Read Jonathan Duncan’s full review here.

Otelo Burning (South Africa)

The director of the South African hit documentary Surfing Soweto, has returned to surfing with this, her first feature fiction — Otelo Burning. However, the surfing is no longer on top of railway trains into Johannesburg, or dancing off the sides of train-cars returning back to the townships; dusty, electrified and full of impending doom. No, Otelo Burning is about surfing the waves that crash against the South African coast, at a time when apartheid was crumbling, and when young black men and women were facing an apocalypse. No less about defining the self against the harsh and ignorant views of others (exactly as disenfranchised and forgotten youths in Surfing Soweto were), Otelo Burning is lush, sexy, complex and gripping, accompanied by an outrageously cool soundtrack. A must see.

Cursed Be The Phosphate (Tunisia)

And finally, Tunisian filmmaker Sami Tlili’s Cursed Be The Phosphate, which tells the story of the 2008 revolts in the Gafsa mining basin, and more particularly in the town of Redayef. Tlili’s suggestion that these protests were an important precursor to the country’s 2011 Revolution sounded and looked very convincing.

* Deserving mention are also Coming Forth By Day, the long-awaited film by Egyptian writer-director Hala Lotfy; and the harrowing documentary Call Me Kuchu (doc) by Malika Zouhali-Worrall and Katherine Fairfax Wright.

Here’s to 2013.

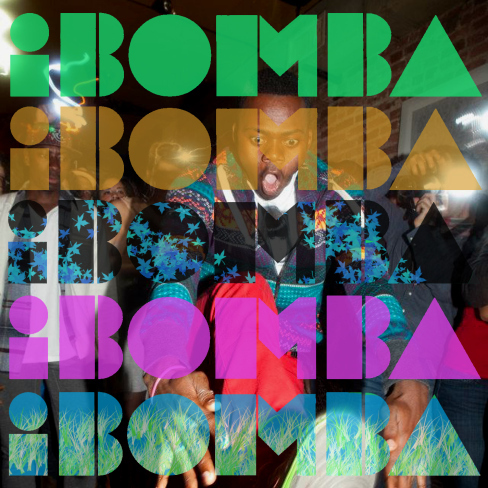

Kuduro’s International Wave

Earlier this month I had the rare opportunity to throw on some of my favorite Kuduro tracks at full volume in back to back succession as part of the first Os Kuduristas showcase at the iBomba party at Bembe in Brooklyn. (Listen and Download: Chief Boima Live @iBomba (ft. MC Fogo de Deus) Brooklyn NY, Dec. 10, 2012.)

The Os Kuduristas brand arrives in New York on the back of a wave of international attention given to the Kuduro genre, with little credit given to the Angolan originators of the sound. The tour is an attempt to rectify that lack of recognition by promoting Kuduro as a distinctly Angolan phenomenon that incorporates elements of local fashion, dance, music, and other elements of urban Angolan lifestyle. As a nationalist project, Os Kuduristas does not come to us without its share of controversy. However, it does mark an interesting chapter in a game of national identity politics as an African nation (in the form of a private company) takes a page out of the U.S. State Department’s playbook, and taps into a socially marginal youth culture to assert its belonging and participation in global society.

I first became aware of Kuduro when searching out Angolan Hip Hop on the Canal Angola website back in 2006 (I hadn’t realized it then, but my first exposure was through a Jamie Foxx routine). I was introduced to it as a ghetto music, rejected by the upper classes in Luanda, and wildly popular amongst youth living on the margins of Luanda’s socio-economic life. At that time Kuduro wasn’t huge on the international radar, but I was to soon become part of a wave of international bloggers, djs, dancers, producers, singers, and young people around the world who would pick up on the sound incubated in Angola.

In that initial international exposure, non-Angolans briefly entertained questions of authenticity, as it was still widely recognized as distinctly Angolan. Web savvy Angolans who were experiencing the culture first hand contributed to these ideas. Frenchman Frederic Galleano would be the first Northern DJ to venture to the country to collaborate with people on the ground. At that time Galleano was quoted in interviews saying that the only real Kuduro comes from Angola. His project would spark some attention in France and set the stage for mainstream integration of Kuduro following in the wake of the Coupé-Decalé explosion in Paris.

The US-based record label Mad Decent did a National Geographic type podcast on the genre, and without any form of formal international distribution Kuduro started to enter the vocabulary of Internet-savvy young Americans and Europeans. I remember at that time it was often just characterized as the “next Baile Funk” in international media, and hipsters in the Northern capitals paid it some brief attention before moving on to the next black music from a strange and exotic place (like Chicago).

The first major international group who spoke of doing Kuduro was Lisbon based Buraka Som Sistema, who were a group of mostly Portuguese young people who heard the sound from peers and amongst neighbors in their multicultural and cosmopolitan city. Buraka Som Sistema would come to define Kuduro for much of the genre’s audience outside of Africa. DJ Znobia was also an early star, and he would even appear alongside Buraka Som Sistema on a Mad Decent produced EP. But it was actually Costuleta, the Angolan amputee based in Paris who spread the genre across the rest of Africa, and beyond Northern hipster circles.

(Children in Nimba County, Liberia singing Tchiriri)

With his song Tchiriri, Costuleta enjoyed Macarena levels of fame in the Francophone world. But this success didn’t come along without its own share of controversy. Oddly Costuleta, concerned with authenticity himself, allegedly covered the song which was originally performed by Magnesio, an artist still based in Angola.

This international attention was perhaps unprecedented for Angola, and it probably caught a few people off guard causing many Angolans to react. Specifically, I remember hearing complaints that Cape Verdians didn’t do real Kuduro, or that Buraka Som Sistema wasn’t really a Kuduro band. But, I also remember at some point seeing some Buraka Som Sistema’s songs near the top of the Canal Angola charts so there was definitely a transnational conversation going on. Also, by this time people like DJ Marfox and his crew in Lisbon were running their own Kuduro clubs, and crafting their own underground sound, that strayed a little from the Luanda sound, but still carried a strong Angolan identity.

After this initial exposure, Kuduro spread fast in the Lusophone, Francophone, and Spanish-speaking worlds through mainstream media channels. Major labels joined the production and promotion of artists such as Costuleta (who is signed to Sony France). And Buraka Som Sistema became one the world’s most popular touring bands. Kuduro also made its way into underground channels in unexpected places. I come across versions of Kuduro from independent artists in places as far removed from Angola as the Dominican Republic, St. Lucia, and Martinique. In fact it has become so popular in the Caribbean that one can come across Kuduro bumping out of house parties when walking through Brooklyn on Labor Day Weekend.

Perhaps the first official international release of Angolan Kuduro of up-to-the-time hits from the streets of Luanda was Akwaaba Music’s compilation album Akwaaba Sem Transporte. It was at this time that Benjamin did the above interview with Kuduro producer Killamu who talked about the lack of material support he was receiving while being one of the most popular in Angola. Interestingly, Kuduro retained a marginalized status in Luanda during most of this initial international exposure. Costuleta recounts that being a music from the ghetto, it was associated with violence, and Kuduro parties were often the target of police raids. Considering this, it is interesting that soon Kuduro would start to take a more central role in the promotion of Angolan identity abroad, and Hip-Hop would come to bear the weight of government attacks.

(Batida and Ikonoklasta’s political take on the genre)

The acceptance of Kuduro music and culture amongst the more elite Angolan audiences perhaps had to do with the success Cabo Snoop was able to enjoy in other African countries after winning Best Lusophone song at the MTV Africa Music Awards. Snoop’s Windeck track became a staple at African parties across Africa, and its high production value, brightly colored, global youth oriented video (skinny jeans and all) introduced the world to another possibility for the representation of Angolan reality, one beyond slums, war, and violence. When Fat Joe went to Luanda to perform at a concert he jumped on a remix of Windeck, as if to signal to the hometown crowd that the homegrown genre had officially arrived on the international stage.

Kuduro’s international wave would perhaps hit its peak when Puerto Rican Reggaeton superstar Don Omar hopped on the remix for Portuguese pop singer Lucenzo’s Danza Kuduro. Lucenzo and the Don really just appropriated the name more than anything. The lack of representative fashion, dance, or even musical style is perhaps a perfect example of the misappropriation of a culture by a major international music label.

It was in this particular context that Zedu dos Santos (Coréon Dú) decided to launch his Kuduro project. He had the means to put together a brand and push it in Europe and the United States. When talking to friends who were better informed about the project than I, I was told that perhaps not all Kuduro artists would get their proper due because they didn’t have a close relationship with the Da Banda or Semba (the companies Coréon Dú runs or is associated with). Are the artists involved with the Os Kuduristas project the most relevant or representative in Angola? Probably not. What’s more, the campaign doesn’t reveal any of the intricacies of urban life in Angola, or really document any of the politics that are lurking just underneath the surface. It’s an advertisement for a country, promoted as a brand, with a campaign built by a significant budget, and run by a private U.S.-based company. But, perhaps that’s what it takes in this day and age to be seen as an equal contributor to our contemporary global cultural conversation. If Os Kuduristas is problematic, there’s no one to blame for its existence but perhaps us, the international community and the media.

As a final note, the conversation around cultural ownership, authenticity, credit, and fairness isn’t contained to just Angola. Any nation or local community that doesn’t have the resources or influence to ensure the local integrity of its cultural production must do so on the terms set-out by more powerful nations; Jamaica and Ghana are notable examples. Wrestling with these issues is something that is very important to me, and remains a major motivator of my own intellectual explorations and artistic practices.

December 22, 2012

Weekend Music Break

Here’s a resolution for the new year: to feature more Togolese pop. If you don’t know who the above Toofan duo is, google “Cool Catché”. Kuduro on the other hand we can never feature enough — this is a new video for MC Maskarado:

Don’t miss this week’s NPR piece on kuduro by the way, “The Dance That Keeps Angola Going”; they interviewed AIAC’s Marissa Moorman for it.

Next, from Uganda: Vampino and friends (arriving “from far”) visit a rural village; a party ensues. A different kind of dance-hall/pop/(add style):

Gambian artists Xuman, Djily Bagdad, Tiat and Ombre Zion take a stand ‘Against Impunity’:

South African Tumi Molekane directed a video for MC Reason (who is signed on Tumi’s record label):

Talking about labels…here’s a new video for South African rapper Kanyi. The story is funny-sad, but probably quite real too:

A video for Fatoumata Diawara’s song about men trying their luck crossing the Mediterranean to get to Europe. Here’s a translation of the lyrics.

Malian trio Smod (remember them) is all for ‘a united Mali’:

Wonderful new video for Asa’s Bond-esque ‘The way I feel’:

And one of the albums I’ve been listening a lot to this year — more about that next week — is Carmen Souza’s Kachupada. This is her version of Cape Verdean artists Humbertona and Piuna’s 1970s classic ‘Seis one na Tarrafal‘:

December 21, 2012

Why would the BBC care what FW de Klerk thinks?

Reporting on President Jacob Zuma’s landslide re-election as leader of South Africa’s governing African National Congress (ANC) on Tuesday, the BBC sought the opinion of former apartheid ruler F. W. de Klerk. De Klerk “… told the BBC that a significant proportion of the South African population were unhappy with Mr Zuma.” It then quotes the former dictator as saying “If the head of state loses the respect, I think that person loses the capacity to govern effectively. I think it would be in the best interest of South Africa if there can be a change of leadership in the ANC.” Who cares what de Klerk thinks about Zuma?

Does he represent any constituency in South Africa? Does he have any moral authority to comment on the democratic process within the ANC itself and South Africa as a whole? Did his National Party tolerate Africans expressing their opinions about politics to the international media during the apartheid era? What chutzpah!

Unlike Zuma, de Klerk never stood for office in a democratic election. Unlike Zuma, de Klerk never received the mandate of the overwhelming majority of South Africans. Unlike Zuma, de Klerk was never subject to any popular verdict of his leadership via a follow-up election. De Klerk owes his position as a former head of state to a totalitarian, racist system that through violence guaranteed rights and protections to a minority at the expense of an exploited and oppressed majority.

Why does the BBC think de Klerk’s so-called analysis is worthy? In the dominant liberal historical discourse–which a global news organization like the BBC unfortunately has fallen prey to–De Klerk is usually portrayed as a brave figure: that he had extended a hand to the ANC, negotiated the end of Apartheid, and that he was rightly was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize (along with Nelson Mandela). The facts were, however, that de Klerk had no choice but to sit down with South Africa’s liberation leaders; that the South African army was decisively defeated by the Cubans in Angola; that sanctions against his nation were crippling the economy; that the popular struggle against apartheid could not be crushed by force; and that right before he left for Oslo to receive the Nobel in 1993, de Klerk okayed a raid by a state-sanctioned death squad that killed five children in the then Transkei—hardly if ever enter into this historic revisionism.

What do South Africans think of de Klerk? Do they value his opinion? In particular, do they care what he has to say about their elected President? The short answer is de Klerk is irrelevant to South Africans today.

The BBC would have been better suited to interview Thabo Mbeki or Nelson Mandela, since they have had experience of governing a democracy in South Africa. Or they could have asked one of Zuma’s former cabinet ministers or a senior civil servant. Whatever you make of Zuma (and at AIAC we don’t all endorse Zuma’s performance as president), both Mandela and Mbeki have repeatedly demonstrated their unreserved support of Zuma. Perhaps that is why the BBC has to call up an apartheid-era ruler for a quote?

But this is not the first time the BBC chose to go with de Klerk. In August the BBC’s Africa desk scheduled a “debate on reconciliation” in South Africa. While it’s their prerogative to do so, it wasn’t clear at the time why they chose to do so. In a post announcing the debate, the BBC decided to use de Klerk as an analyst of sorts (along with someone from the equally problematic South African Institute of Race Relations). This was soon after de Klerk told Christiane Amanpour on CNN that Apartheid had been beneficial to its black victims. Like now, we took the BBC to task on Twitter. You can read that exchange here.

Social Media in Africa’s Revolutions

[image error]

I recently visited the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Art (better known by its acronym MoCADA) in the Fort Greene section of Brooklyn to view its current exhibition: NEWSFEED: Anonymity & Social Media in African Revolutions and Beyond. Running through January 20, the exhibition is part of a larger curatorial series with satellite exhibitions at the nearby 2AC Gallery and Long Island University Humanities Galleries. The works on display “investigate global interconnectivity and how anonymous parties define, construct, and support uprisings in Africa via social media.” Some of the artists featured include Delphine Fawundu-Buford, Jasmine Murrell, and Mohau Modisakeng (that’s “Badisa [Shepherds]” by Modisakeng above). Much of the exhibition appears to have been inspired by the unfinished Egyptian Revolution and the larger ‘Arab Spring.’

The MoCADA is one of the most underrated museum/gallery spaces in New York City. Although the space it occupies (on Hanson Place and around the corner from the new Barclays Center) is tiny, the curators have a real knack for making the most of said space. Moreover, the museum’s founder, Laurie Cumbo, is an endlessly impressive human being who seems destined for big things. That said, I found myself a bit disappointed by this particular exhibition’s offerings. This could simply be due to the fact that I did not visit the other two satellite exhibitions, of course. Yet, I felt that many of the works lack the degree of nuance and subtlety I have come to expect from the MoCADA’s exhibitions.

But I did appreciate the exhibition’s use of a wide range of media, from painting, to photography, sculpture, computer animation, and beyond. There was even a short documentary from the My Africa Is series, which presented a number of interviews with various experts and professionals (including AIAC’s very own, Sean Jacobs) discussing some of the ways African entrepreneurs are using social and new media.

Perhaps the most exciting thing on display is a beta version of a tablet/smart phone application created by Sian Morson of Kollective Mobile. The app conglomerates Africa-specific discussions taking place on various social media platforms (primarily Twitter) and groups them by country. The interface is set up so that users can tap different countries on a map of the continent, opening a specific page for that country. These individual country pages provide users with a brief prompt containing basic information on the country and next to this, an outline of the country’s borders. Within the borders are a number of images corresponding to Twitter users’ profile pictures, which one may then tap to read their tweets. The app contains a few glitches (the Tweets are not necessarily updated in real time, for instance) and not every country has its own page, but it is quite captivating nonetheless. The app is not available for download yet, though when I asked one of the museum’s staff, I was told that they were trying to make it available for free download once the exhibition has closed. Until then, it’s worth making the trip to the MoCADA to check it out along with the rest of the exhibition.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers